He’s Never Felt More Naked

A conversation with illustrator Barry Blitt (The New Yorker, Air Mail, Entertainment Weekly, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF MAGCULTURE LIVE

Barry Blitt wants you to laugh at him, not with him. Because laughing with him means you’d have to be where he is. And—“thanks very much!”—but he’d rather not. He’s happy enough just drawing for himself.

“I’m trying to make myself laugh,” he says. “That’s the point, that’s part of the process, it’s as un-self-conscious as possible.”

Blitt is a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and an Art Directors Club Hall of Famer. He’s been called one of the “pre-eminent American satirists.” And, in a recent interview, he was asked what makes him laugh. His answer? “Awkwardness. When people are uncomfortable.”

Which, as it turns out, is right in Blitt’s, dis-comfort zone. In the introduction to his 2017 book, Blitt sums up the effect of all that attention and all those accolades: “I’ve never felt more naked,” he wrote.

Artists are especially prone to self-doubt. They pour their hearts and souls into their creations, whether it’s writing, or photography, or illustration—or cartooning. Then they have to find the courage to put that work out into the world. A world full of critics, and judgment, and rejection.

“I don’t see how the work can be separate from who you are,” Blitt says.

And in today’s explosive media climate, where standing by your work can sometimes mean life or death, Blitt shrugs:

“It’s amazing that I haven’t been punched. But I’m only 65 and, you know, there’s plenty of time for that, I expect. Especially with the hostilities and tensions in the air.”

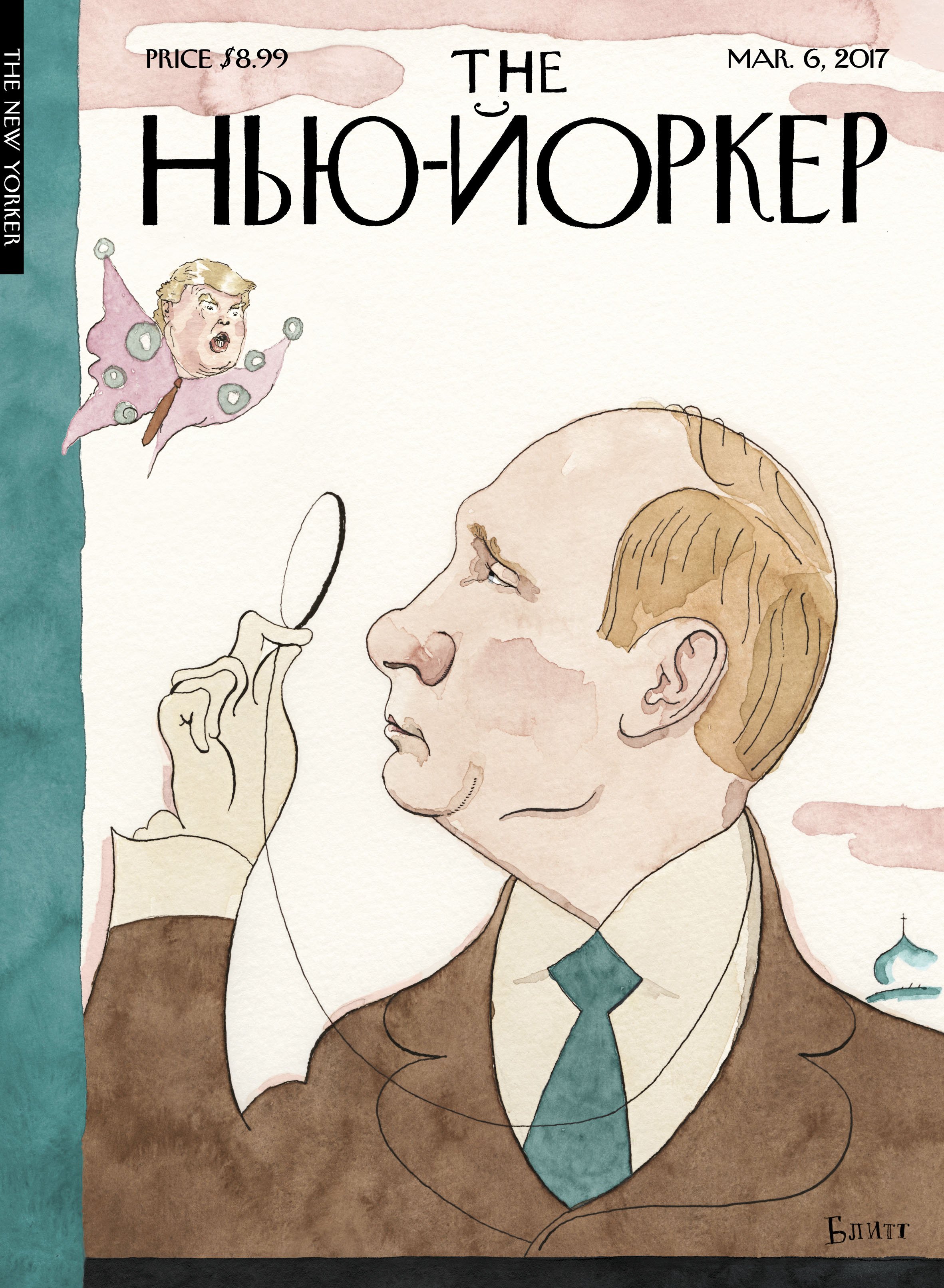

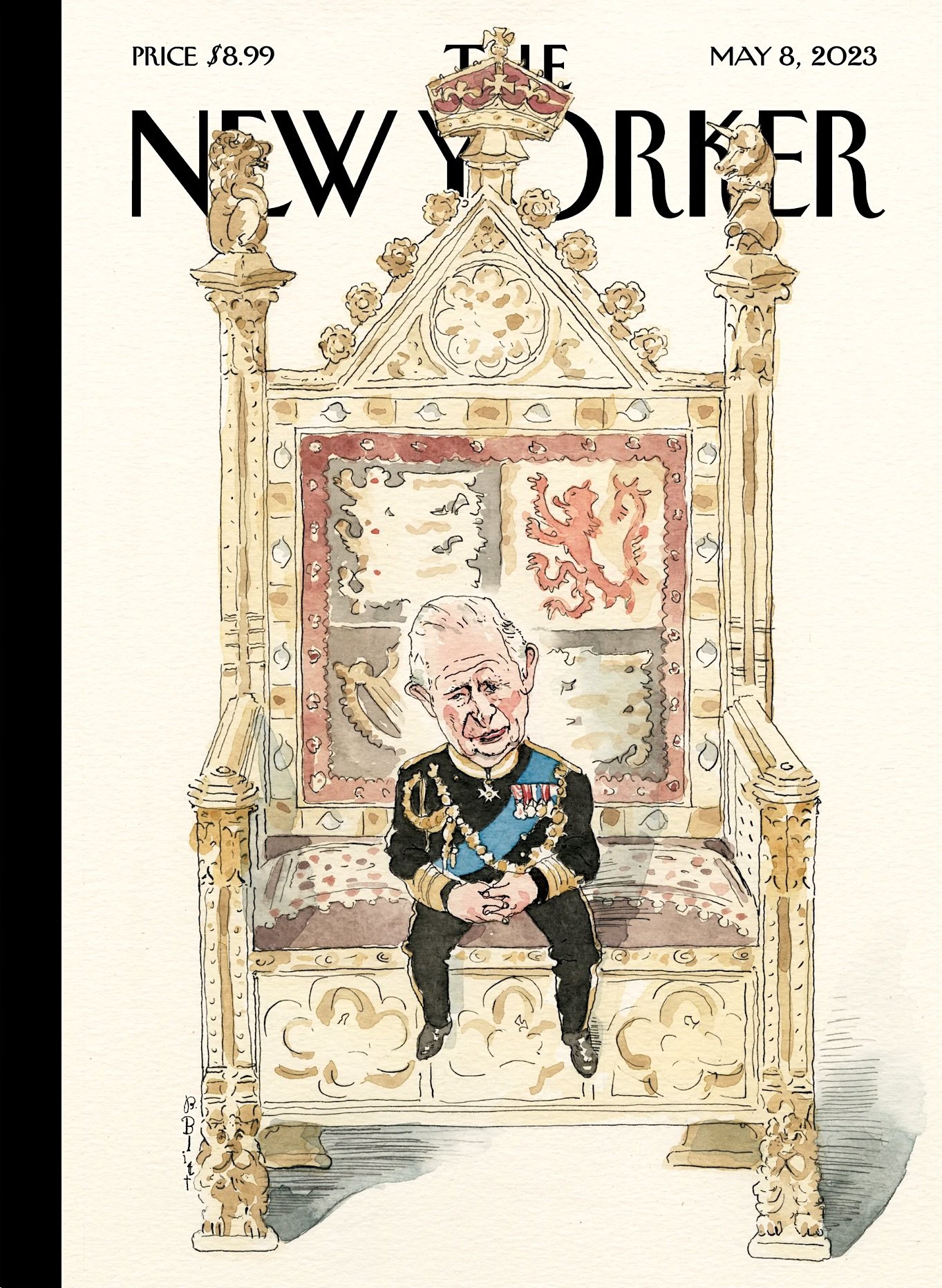

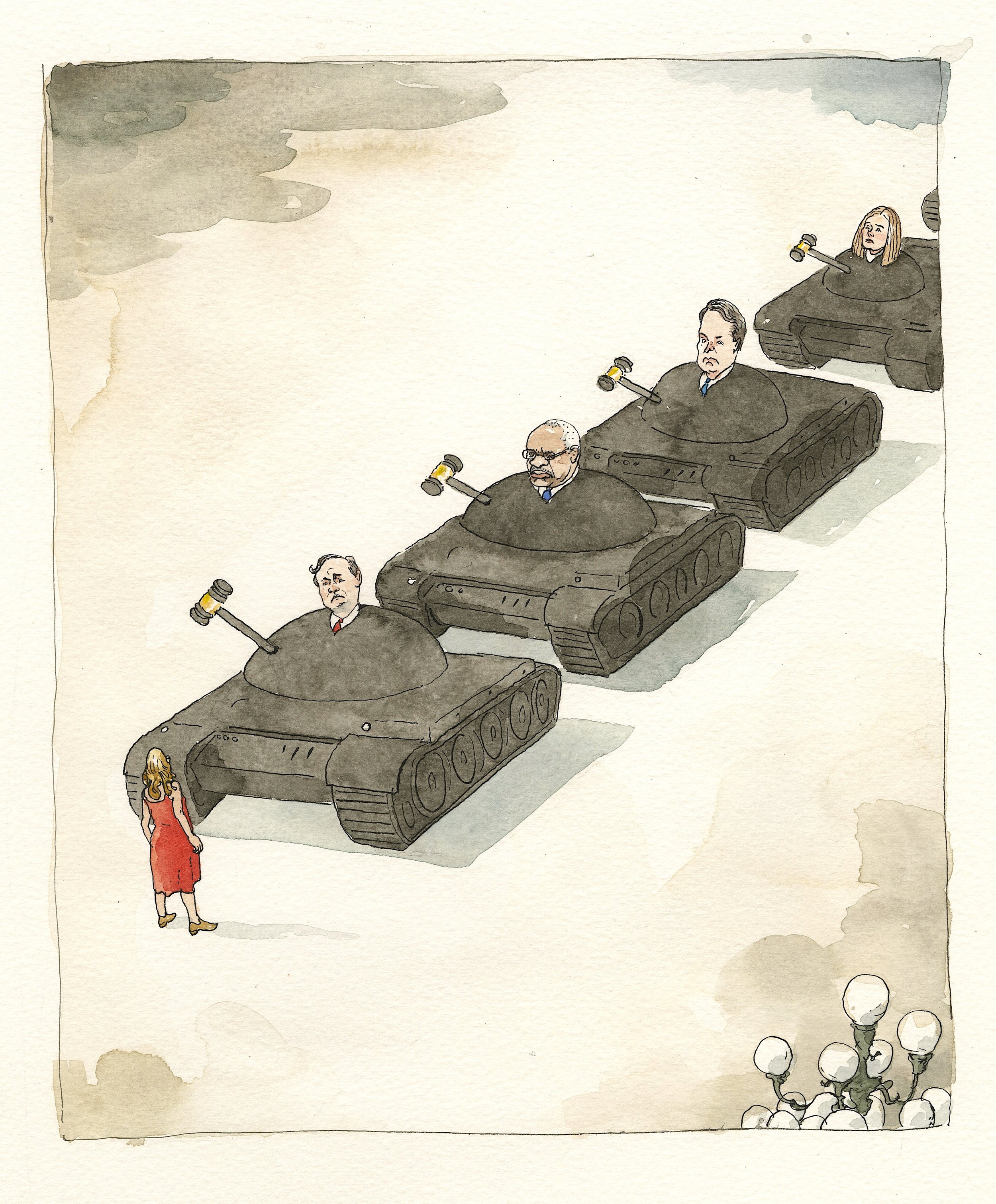

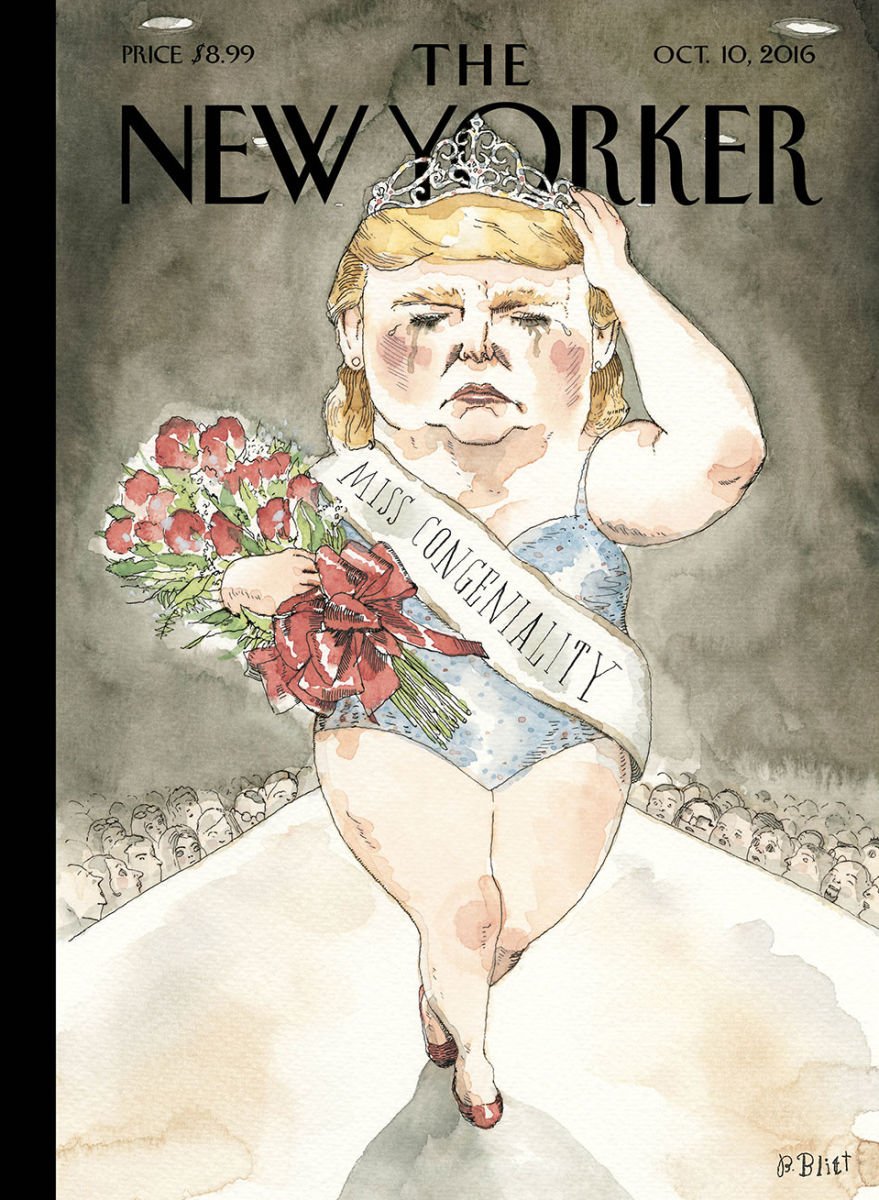

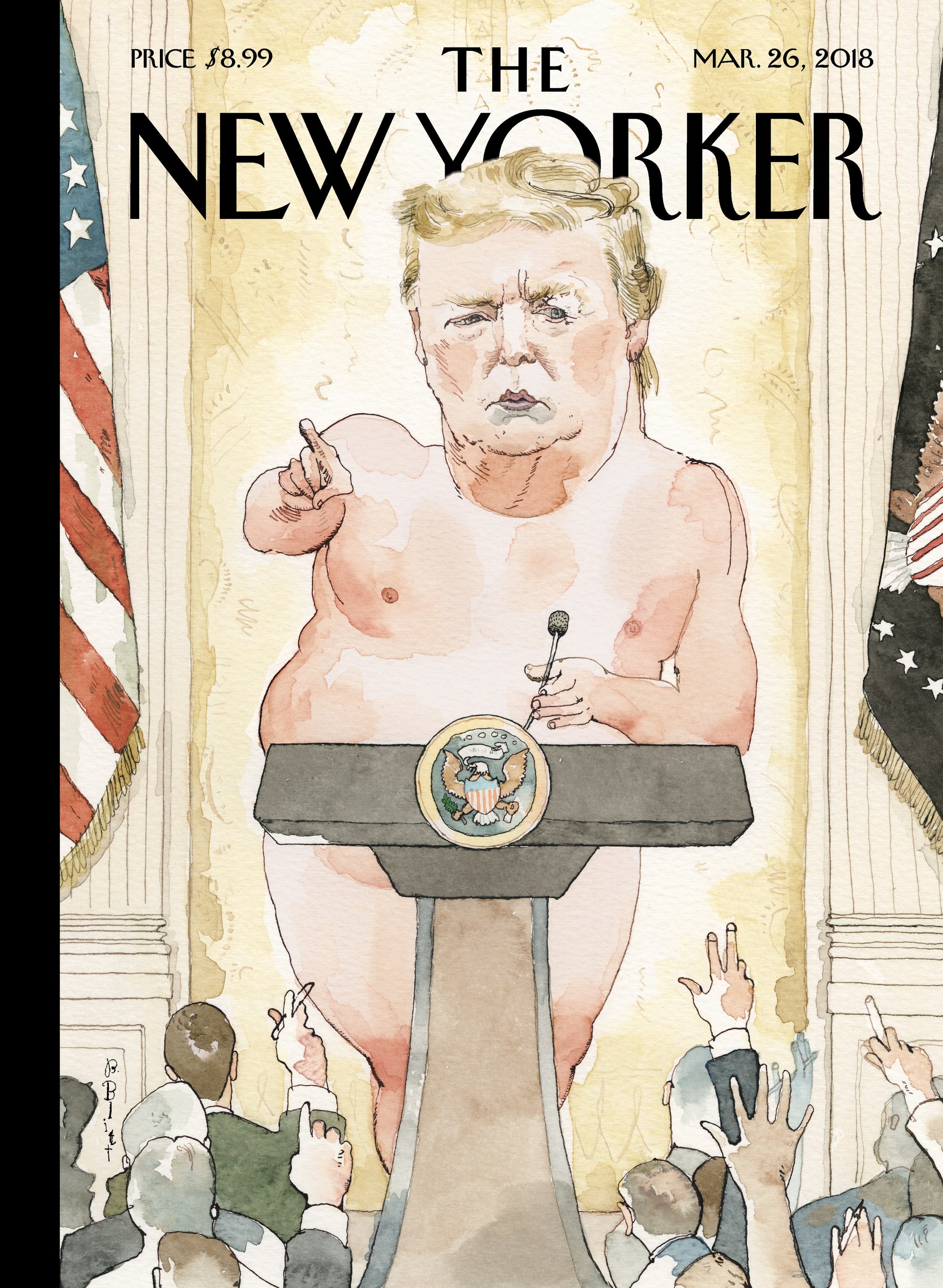

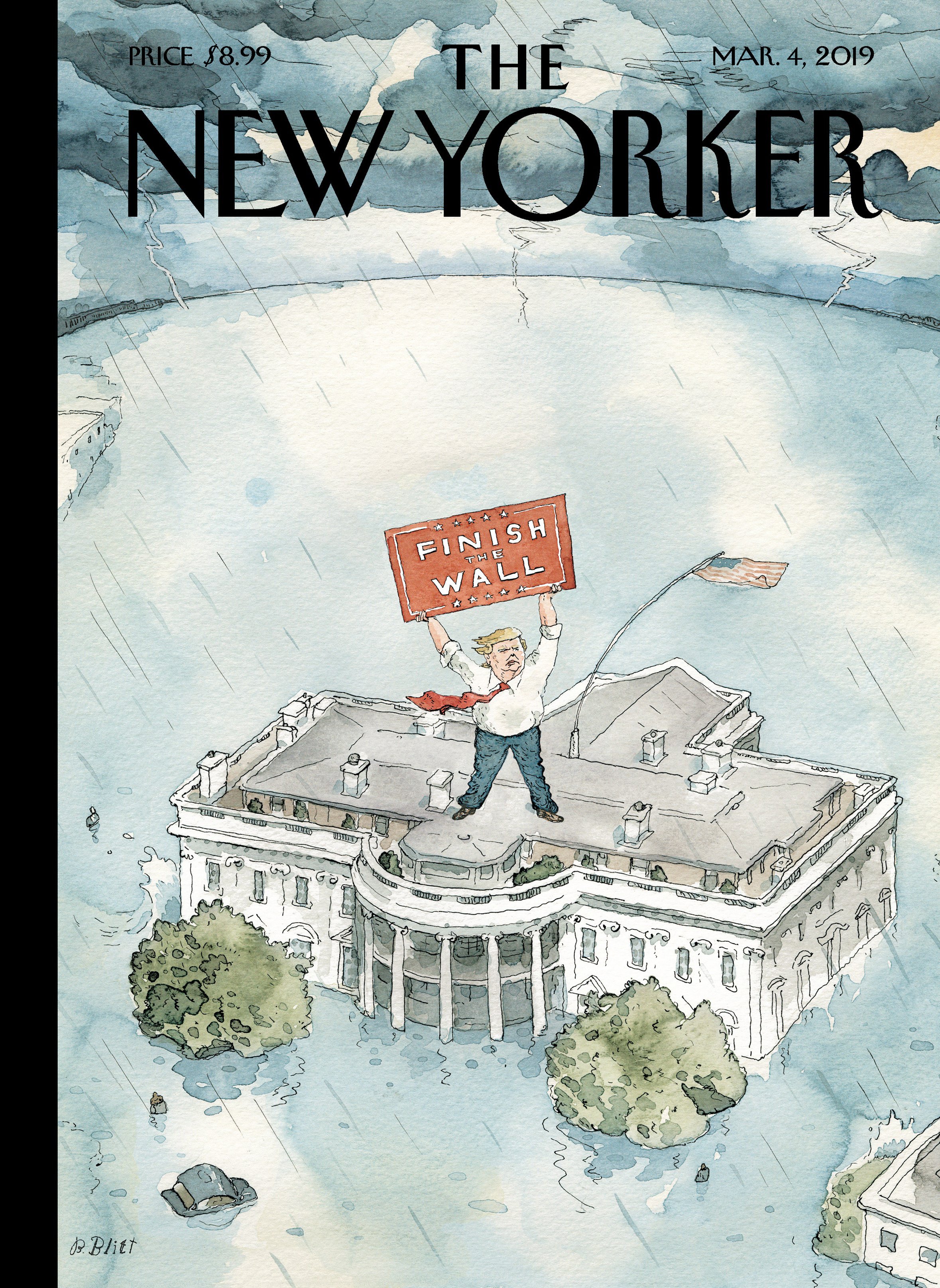

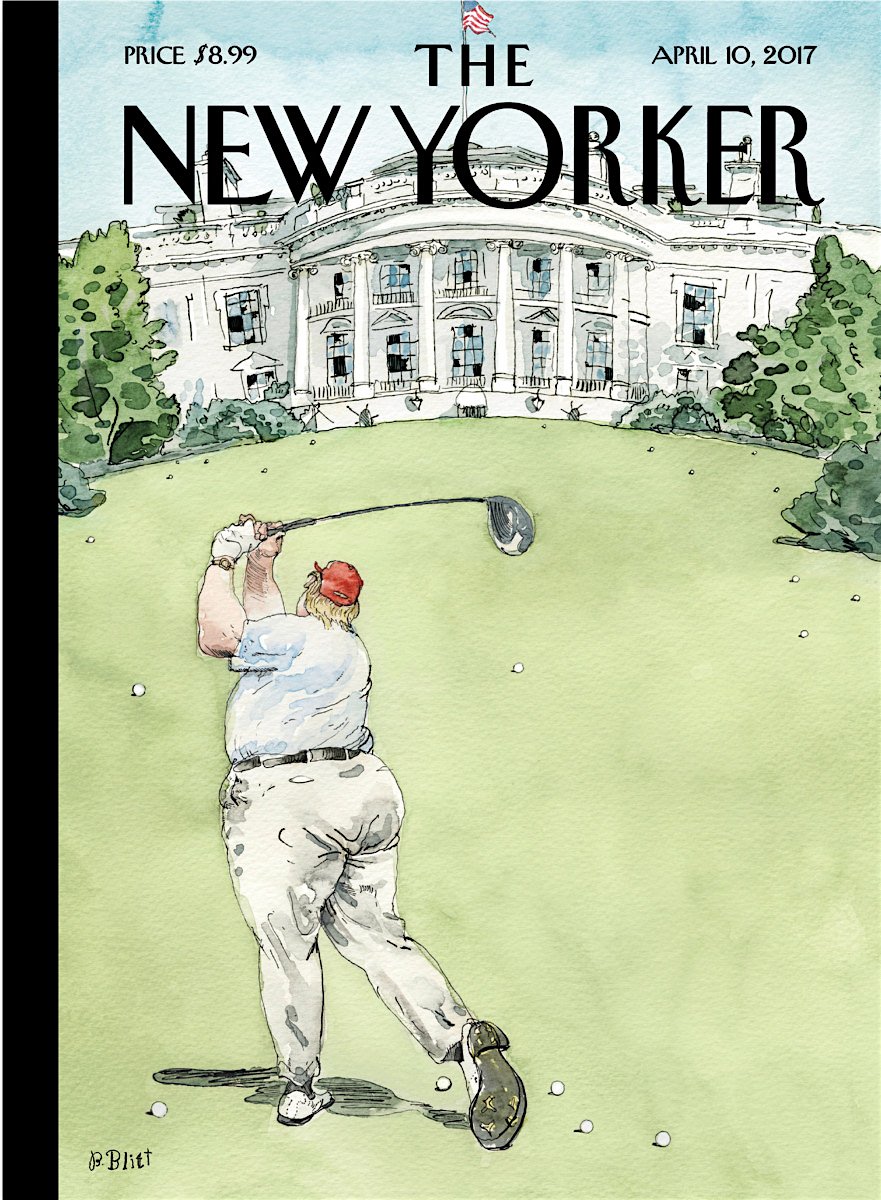

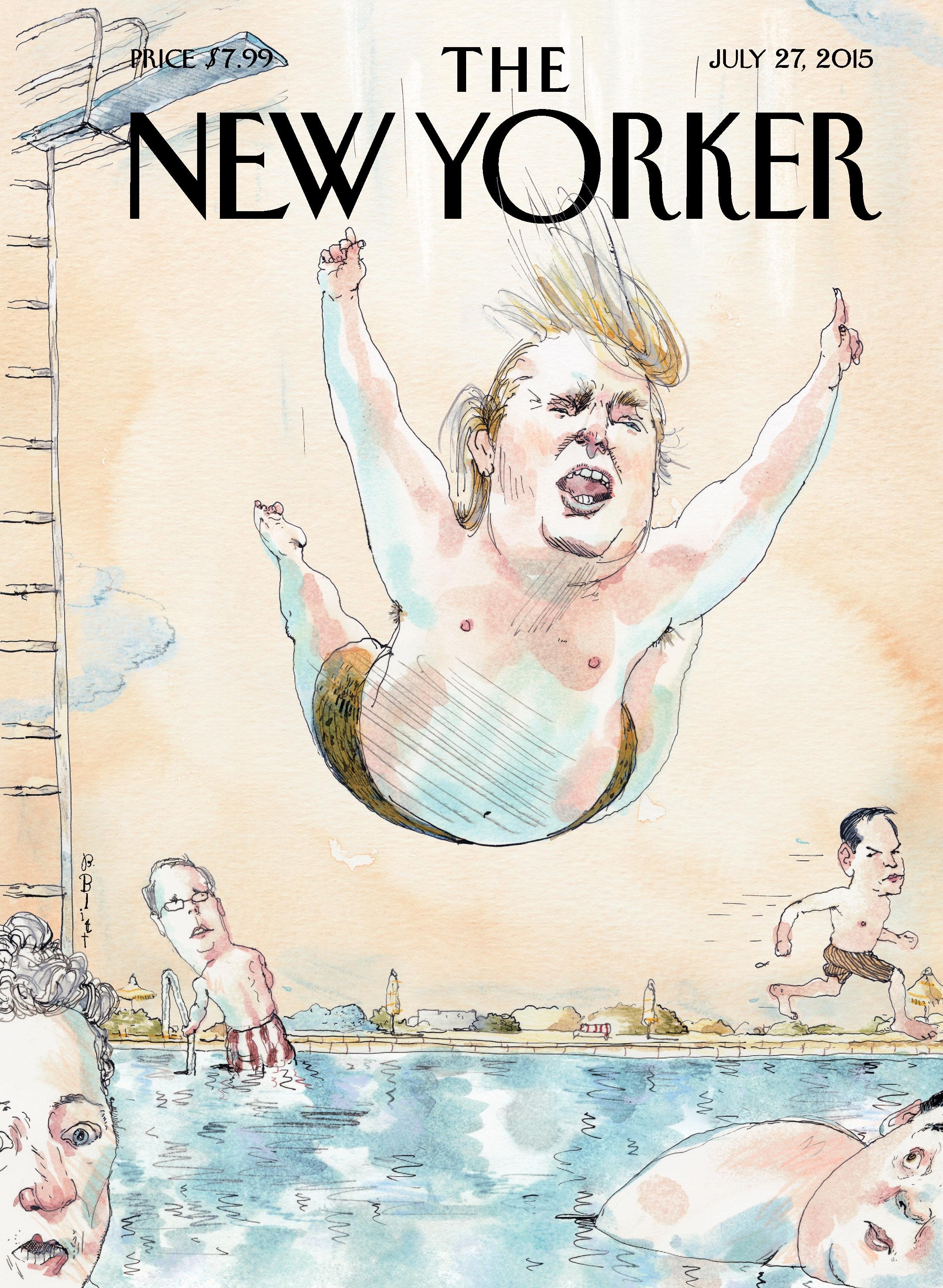

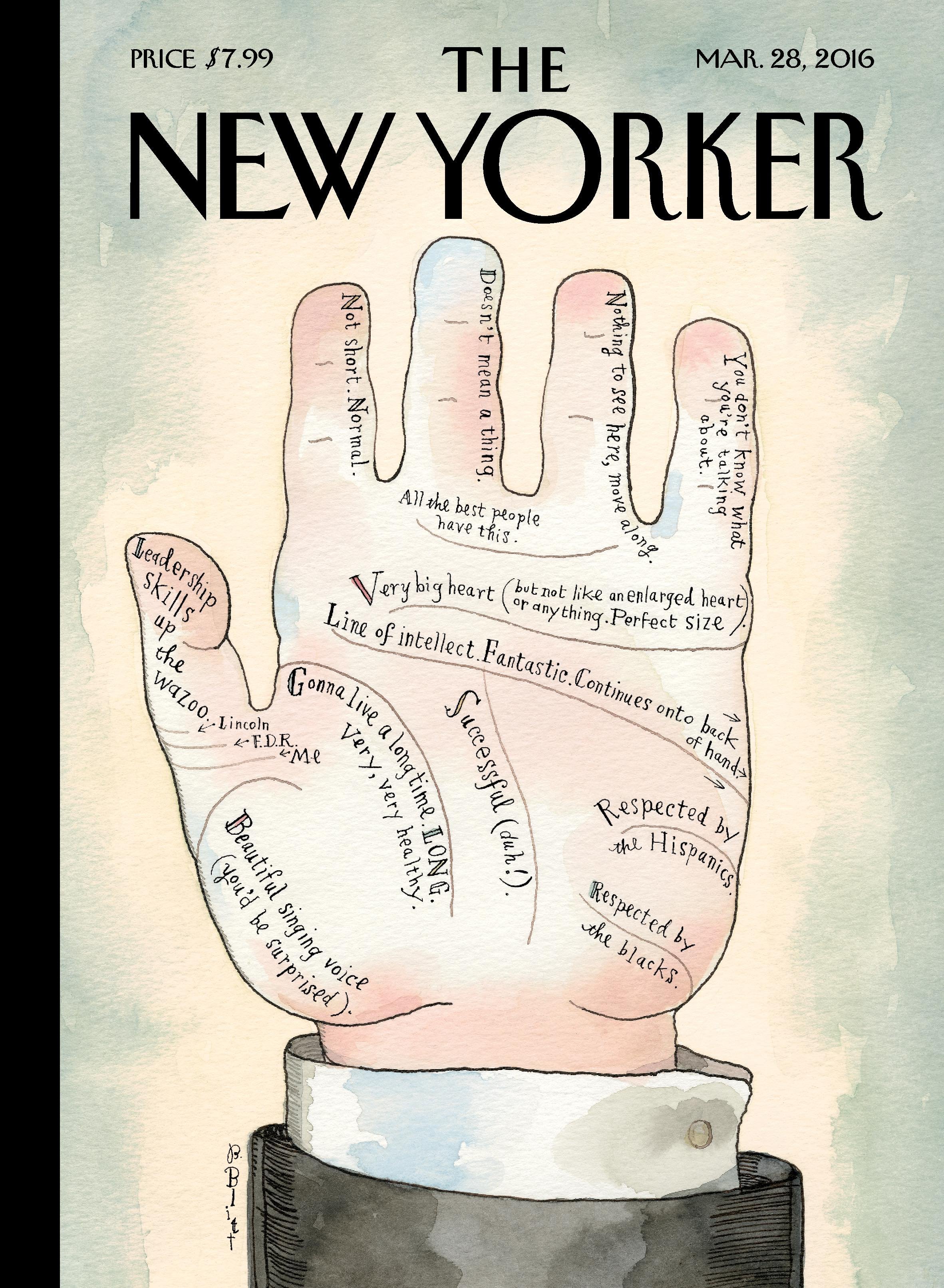

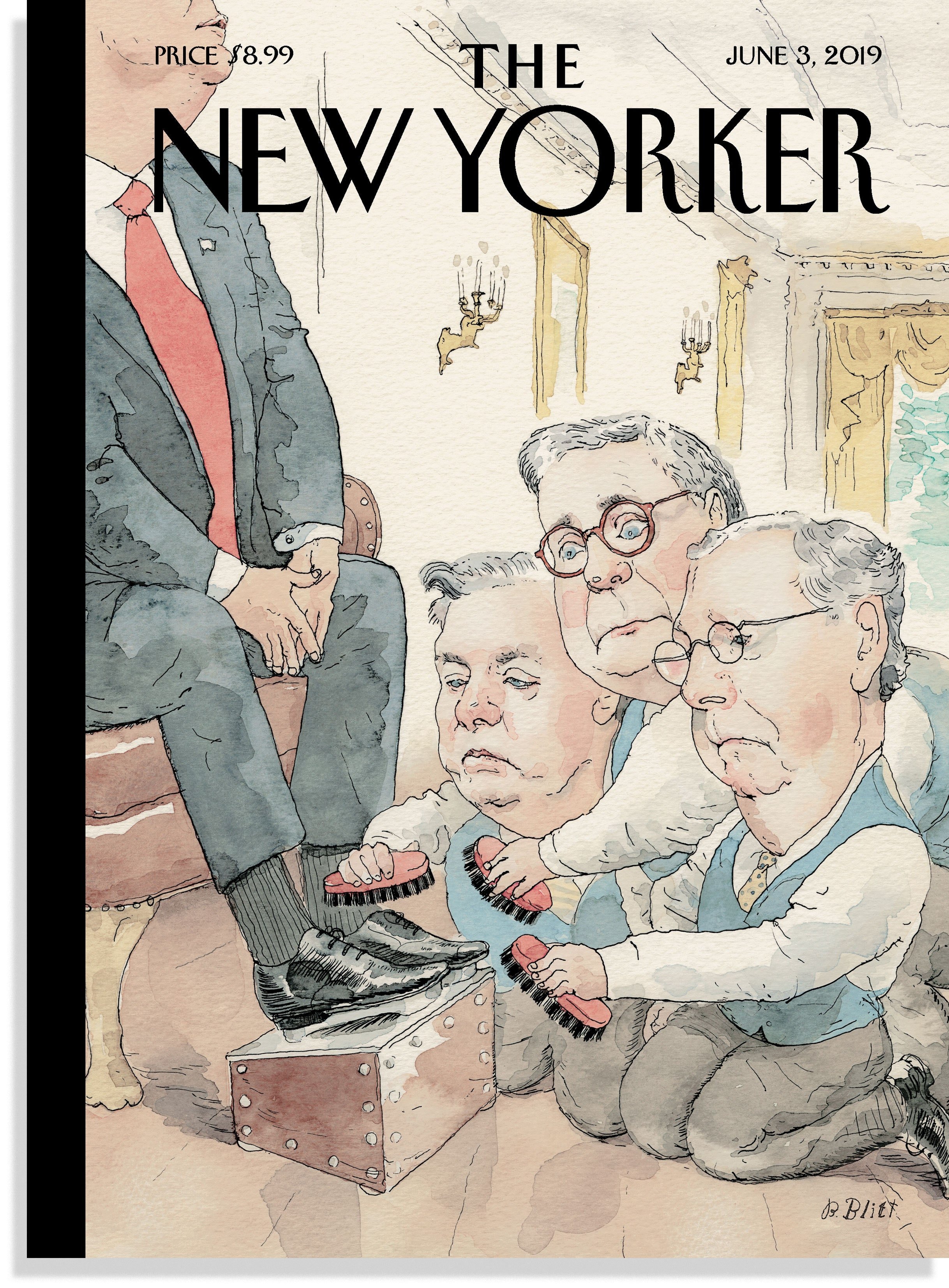

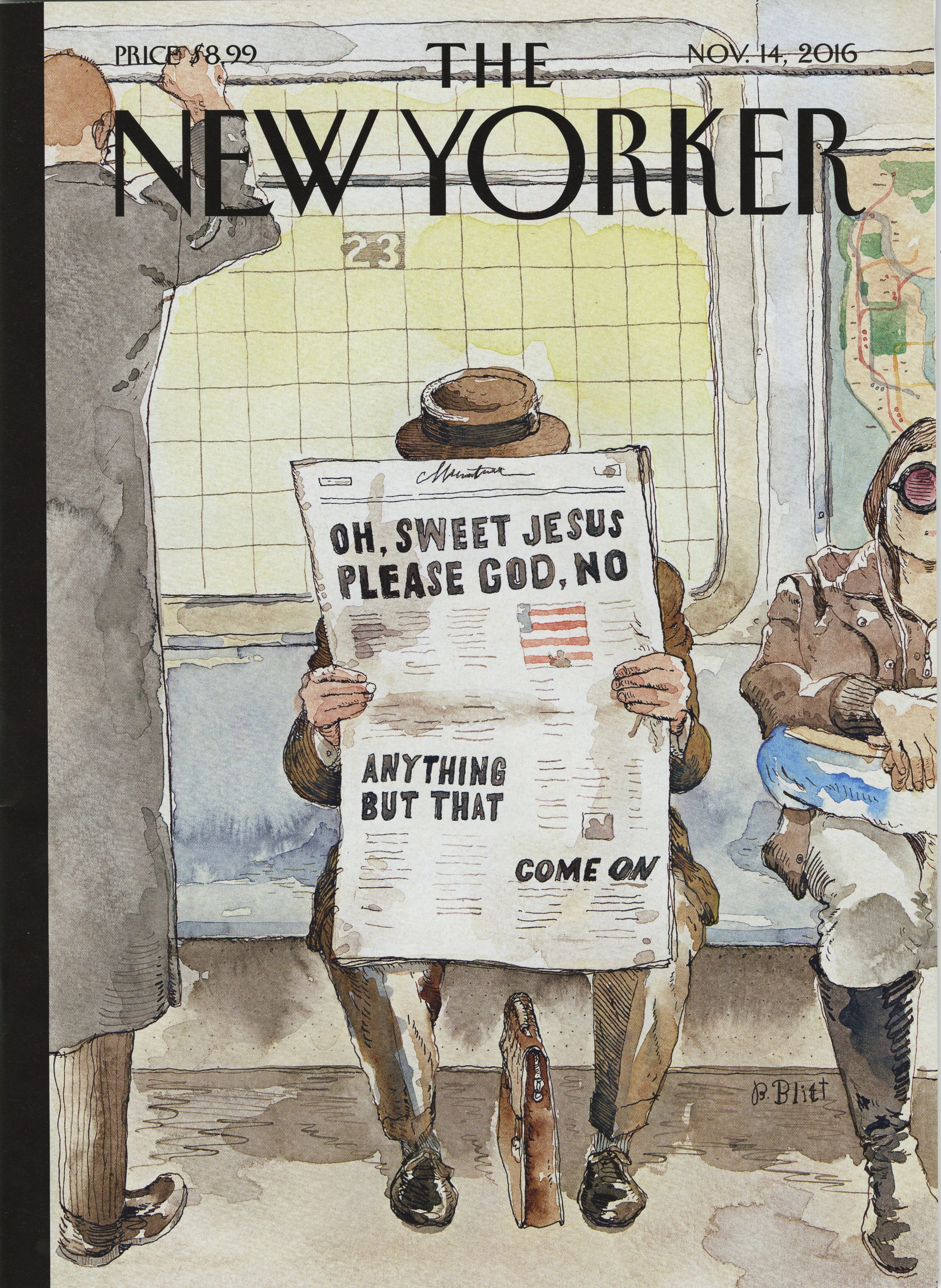

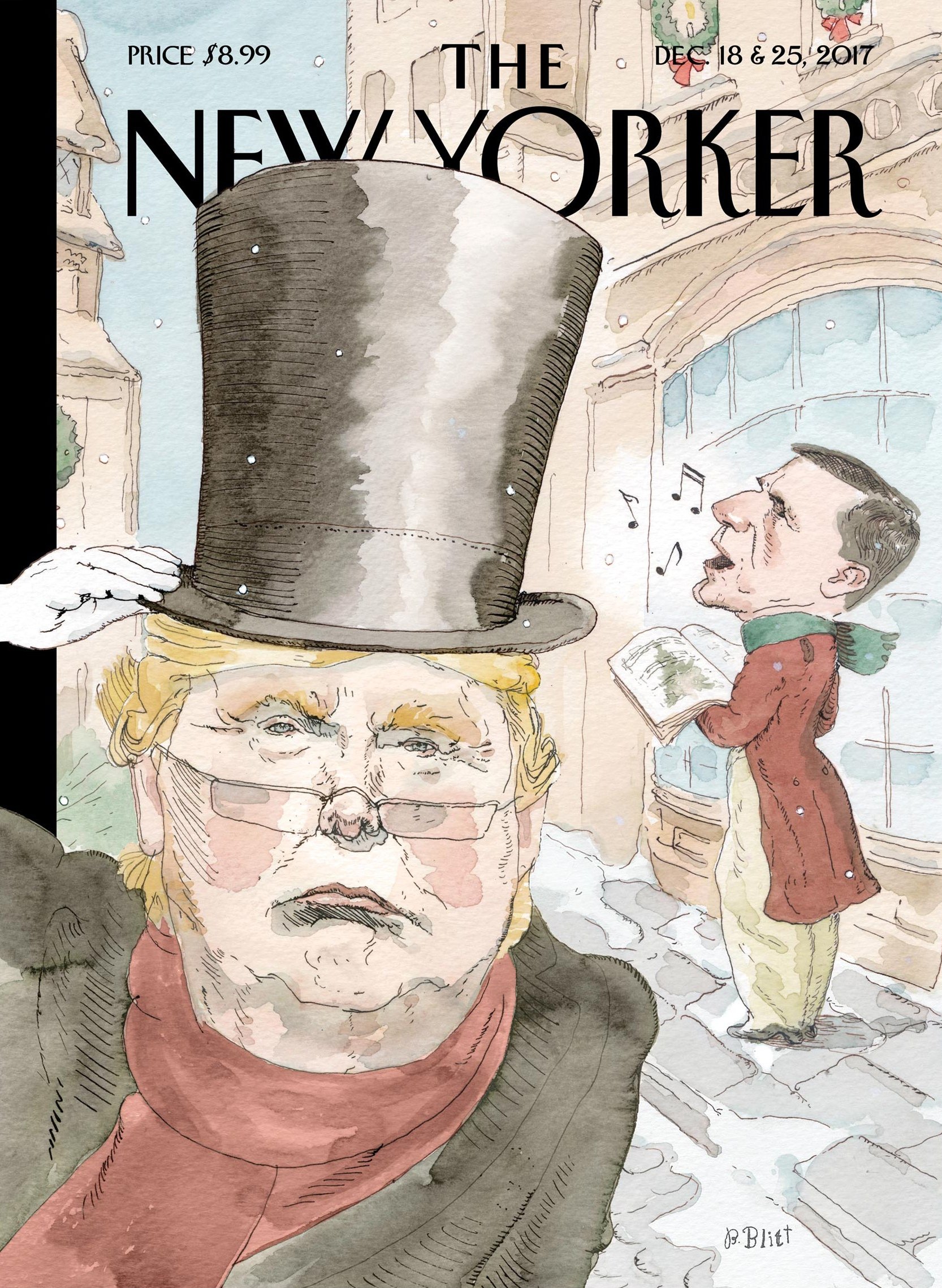

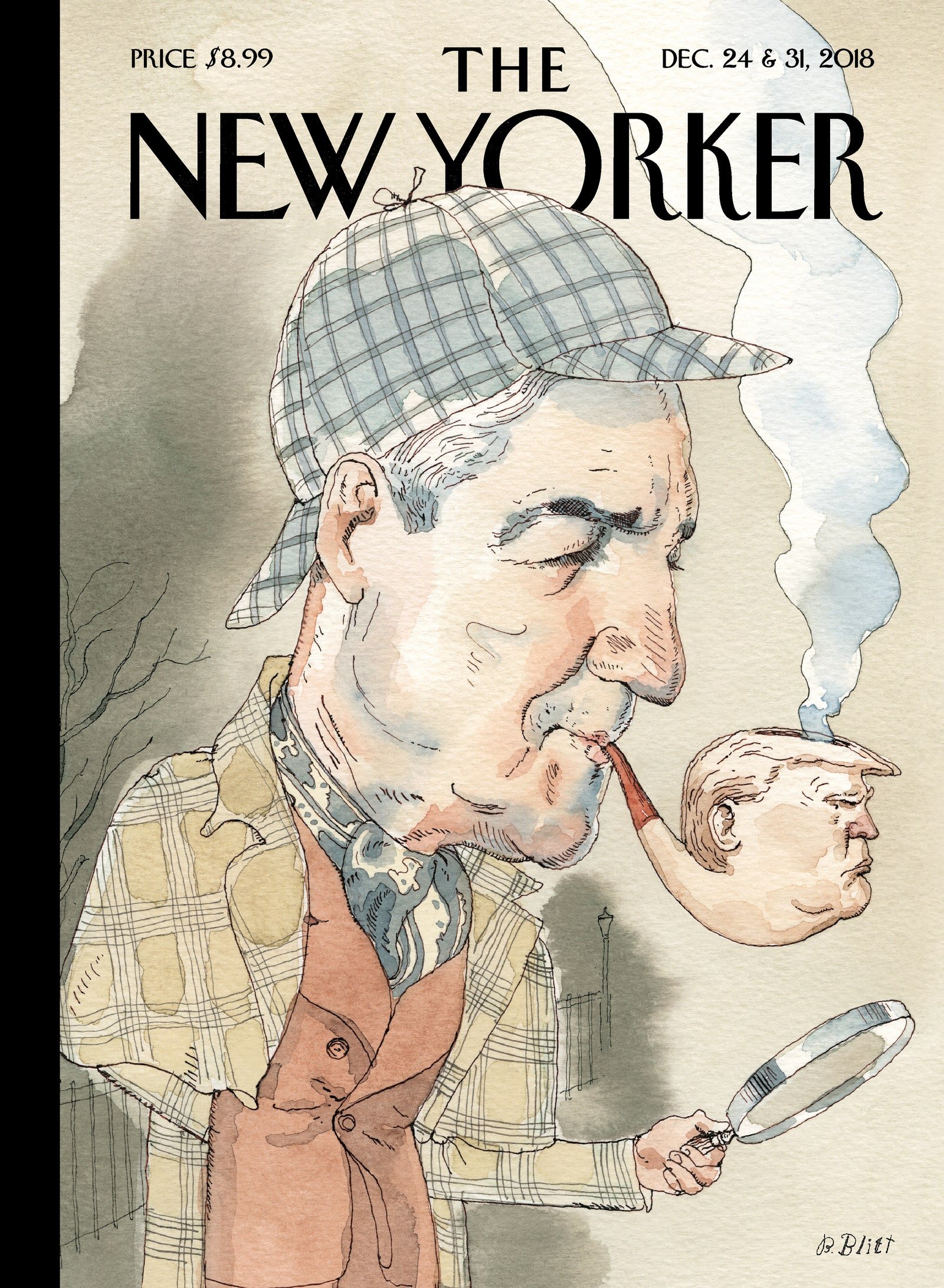

Regardless, Blitt continues to churn out work. He’s completed over 300 assignments for The New Yorker alone—more than 100 of them covers. That work led to his Pulitzer in 2020, “for work,” the committee said, “that skewers the personalities and policies emanating from the Trump White House with deceptively sweet watercolor style and seemingly gentle caricatures.”

We talked to Barry about how, and why, he made a Time magazine art director cry, about who and what makes him laugh, about his biggest paycheck ever, about what weed can do for your creativity, and about fighting every urge in his body to self-edit.

Patrick Mitchell: Women’s Wear Daily used these three words to describe you: clever, incisive, and humorous. Were they talking about your sense of style?

Barry Blitt: Uh, I have no idea, but the three words I use to describe Women’s Wear Daily are “capable,” “timeless,” and “daily.” Buy, no, I don’t think Women’s Wear Daily said anything about me.

Patrick Mitchell: No, they did. You were in Women’s Wear Daily. Anyway…

Barry Blitt: Oh, Peter Kaplan went there. He was the editor of the New York Observer. The much-loved editor of the New York Observer. And I believe he went to Women’s Wear Daily.

Patrick Mitchell: With a mission to amp up their illustration coverage?

Barry Blitt: He did love illustrators. The late, great Peter Kaplan.

Patrick Mitchell: So you went through quite an ordeal to get to New York City back in the—when was it? Late eighties? Early nineties?

Barry Blitt: Yeah, it was December ’89 that I moved down with my then-wife. I like the expression “my then-wife.” I’ve always wanted to introduce someone, “This is my then-wife.” But yeah, what happened was my then-wife, got a job at Sports Illustrated. We were living in Toronto. She was an art director. And it still may be one.

Patrick Mitchell: But in order to work here, you needed, I think they call it an O-1 visa now, but you need to have achieved some sort of level of skill in your chosen profession to be able to work here.

“I think luck plays an incredibly big part of anyone’s—whatever they’re doing. We’re all in a pinball machine here.”

Barry Blitt: This story could take up the whole interview, by the way, because neither of us drove and we had cats and we hired a car to drive us down with our cats. Maybe that’s not as interesting a story as now that I recall it, but yeah, it was complicated for me because she had a visa and I didn’t, but I was already doing freelance work in the States.

So I got here and kept working for quite a few of the same clients, but all my checks were mailed back to my accountant in Toronto who put them in the bank for me.

Patrick Mitchell: In addition to not driving. You also don’t cash checks?

Barry Blitt: No, I cashed checks, but I couldn’t because I couldn’t be working out of here. I wasn’t technically supposed to be living here and drawing a paycheck.

Patrick Mitchell: Where was your first place in New York?

Barry Blitt: It was West 87th Street, just west of the park. Brownstone. [It] had a little backyard. You, I don’t think I knew you then.

Patrick Mitchell: No, we worked together in Detroit, I believe, when you were living in Toronto.

Barry Blitt: Toronto. Right.

Patrick Mitchell: I think the first time we worked together would’ve been ’87-ish. So you were clearly already a legend.

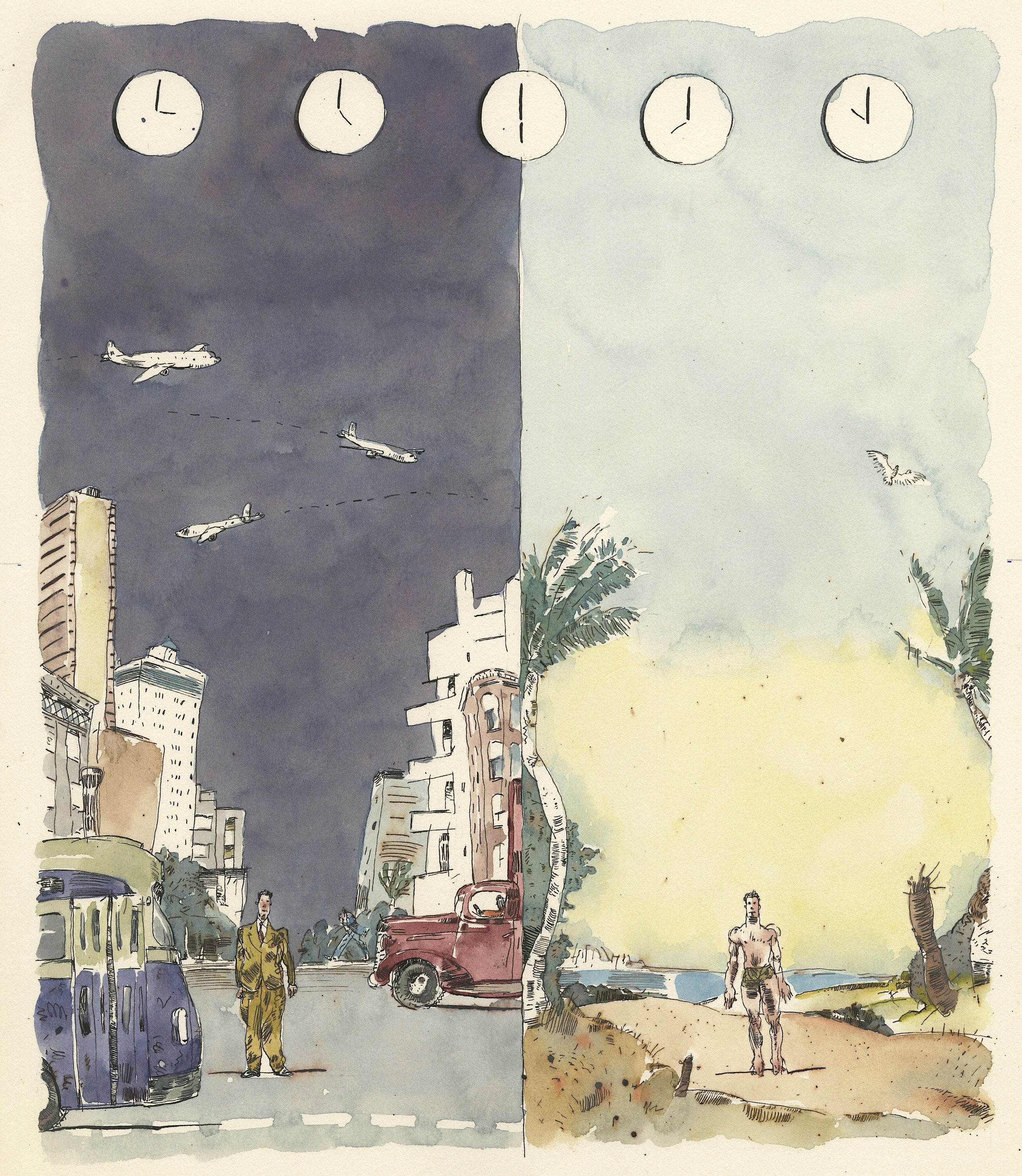

Barry Blitt: I remember the drawing. It was, well, I won’t describe it, but it was split down the middle and it was a night scene and a day scene, and there was a little figure...

My first collaboration with Barry, a full-pager for the Detroit Free Press Magazine, c. 1987

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. So you were on the Upper West Side, off the park. Do you remember—was there a big first meeting in New York as a New Yorker?

Barry Blitt: I remember the first time I went to The New Yorker, I was already living here and I went and met Chris Curry [Illustration Editor at The New Yorker]. And she looked at my portfolio in the waiting room in the hall.

Patrick Mitchell: Before The New Yorker, who were your clients then, as a younger-but-established illustrator?

Barry Blitt: I wasn’t established. I was a young pup. And, yeah, there was, like, Savvy Woman, and there was Cooking Light and, there was Entertainment Weekly. I did a lot of stuff for Entertainment Weekly that went on for a long time. And there was the New York Observer, there was Spy. Spy magazine was one of the first I worked for. Geez, I guess Robert Priest of GQ. And there were sure a lot of magazines. And Fast Company, of course. And Hans Teensma at New England Monthly. They were one.

It’s all who you know, by the way.

Patrick Mitchell: I read that you did a sequence for Saturday Night Live in ’96. I was unaware of that. What was that?

Barry Blitt: That was J.J. Sedelmaier, the great animator. He was doing small segments with Robert Smigel. They did a thing called “Real Audio” where they would take a chunk of an interview with Larry King and Ross Perot, in the case of the one I worked on (see video, below). And then we just did crazy images with the two of them, like in different crazy situations, just skipping randomly from one situation to another.

Blitt’s collaboration with animators J.J. Sedelmaier and Robert Smigel for Saturday Night Live, c. 1986

So they’re sitting in the studio and they’re talking, you hear the talking going on the interview and then, all of a sudden, they’re wearing armor or they’re in a science fiction scenario.

Patrick Mitchell: So it was like an animated version of that puppet show, Spitting Image. How long did you live in Manhattan before you moved out to Connecticut? And I know you lived in Greenwich before.

Barry Blitt: I have a bad temperament. So New York was very exciting for me. I was, like, maybe 30. So technically still alive. But I found the air difficult. And the noise difficult. And so I guess—I moved in December ’89—probably by ’92 I was worn down and we started looking around in neighboring towns. And so I was only in Manhattan for a couple of years and change.

Patrick Mitchell: And then Greenwich, which I assume was for the schools because you had a kid?

Barry Blitt: No. No pup yet. Sam wasn’t born until ’96. So there’s no reasonable explanation why we ended up in Greenwich. It seemed clean and quiet. It was the first place we looked and, actually, walking down the street there was a for sale sign on a house. And the first house that I saw. It was kind of crazy.

Patrick Mitchell: And now you’re in Litchfield?

Barry Blitt: You can call it that. I guess that’s one interpretation.

Patrick Mitchell: And I understand your house once belonged to Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe.

Barry Blitt: Yeah, it’s true. It doesn’t lend me any glamor.

Patrick Mitchell: Speaking of Connecticut, I saw a quote of yours in Politico, where you said “I was made for quarantine. There’s not much call to leave.” You know the pandemic is over, right?

Barry Blitt: Is it over? I mean, I know it’s “officially” over. I know that’s what “they” want you to think.

Patrick Mitchell: You’re like a Japanese soldier on some island in the Pacific.

Barry Blitt: I guess. I mean, you can make fun. But, yes, I’m finding the reintegration into society—not that I was ever, you know, fully part of it—but it’s difficult. I’ve really gotten used to sitting in my room and drawing a bit, playing the piano a bit, you know, whatever. Having a sandwich...

Patrick Mitchell: I couldn’t agree more. Every time I’m out with someone, I have to comment on how really weird it seems. Even though that was only two years, there’s just something that feels unnatural about being in public with people.

Barry Blitt: Right. It’s quite awful. I’m going to Montréal this weekend and I’m really not looking forward to all that not-alone time.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, that’s a perfect segue. I want to hear about your growing up in Montréal. You were born there. Were your parents natives of Montréal?

Barry Blitt: Yeah, my parents are native Montréalers. Their parents came from Ukraine and from Russia and, you know, scattered around that area. But yeah, we were all Montréalers.

Patrick Mitchell: What did your parents do?

Barry Blitt: My father was … he was sort of a crab. Sort of a sand crab. My father was a salesman. He wasn’t happy with what he was doing.

Patrick Mitchell: Tell me about him.

Barry Blitt: Yeah Ron Blitt. I mean, he encouraged me to draw and I shouldn’t have so much hostility really. He was easily irritated and sports was very important to him.

Patrick Mitchell: What did he do for a living?

Barry Blitt: Well, he was like a—he was a peddler when we were younger. Then he inherited some real estate from his father, and he handled that—you know, rentals for tenants—for a while. And then he played a lot of tennis after that. And watched a lot of baseball and hockey.

Patrick Mitchell: And did your mom work?

Barry Blitt: My mom worked at a library for a while before she married Ron. She taught grades one, two, and three, But yeah, she stopped that. And she did do some tutoring while I was growing up, and the little kids would come to the house and I would, you know, make them laugh while she was trying to teach them English or math.

Patrick Mitchell: Siblings?

Barry Blitt: Siblings. Yes. A younger brother, Ricky.

Patrick Mitchell: Where would we find Ricky?

Barry Blitt: Ricky’s in Hollywood writing movies.

Patrick Mitchell: Any movies we’ve seen?

Barry Blitt: He did a movie with the Farrelley Brothers called The Ringer, about a guy who fixes the Special Olympics. And I think he’s working on something now with the Farrelleys again with Jack Black in it.

Patrick Mitchell: So who in your family did you get your humor from?

Barry Blitt: My father made a lot of jokes. I never thought he was particularly funny, honestly. But he was constantly—when he wasn’t incredibly irritated—he would be making a lot of jokes. And I think my brother and I inherited the need to be funny, if not the actual sense of humor. I don’t feel like anything in my sense of humor that’s anything like his.

Patrick Mitchell: So you developed a sense of humor because your father’s was not up to par? Or in order to relate to him?

Barry Blitt: No, I think that it was that the three of us had a need to be funny. I think it was because we were all small, and insecure, and self hating. And I could go on in this direction.

Patrick Mitchell: That all makes sense. It’s a universal theme.

Barry Blitt: It was a coping mechanism and an overcompensation.

Patrick Mitchell: But it worked in your case?

Barry Blitt: I guess so. I mean, I didn’t get beat up ever, which is amazing because I always had a big mouth.

“One of the first to hire me when I moved to New York was Steven Heller at the NYT Book Review. You’d be called in and he would hand you a manuscript and say, ‘Monday.’ And then you would leave.”

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Well, I’m going to get to that. As a kid growing up in Montréal, were you speaking mostly French or English?

Barry Blitt: No, no. We grew up in Côte Saint-Luc, which was mentioned in National Lampoon once as having a higher density of Jewish people than Israel. It was a small neighborhood and every kid I knew was Jewish, pretty much. Jewish and English. We were anglophones, as they call them in Quebec.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, that’s yet another sort of, uh …

Barry Blitt: Contradiction?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, no. It makes you more of a minority, right? In a place like Montréal? Weren’t they really hopped up on speaking French?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. Well that also got more intense later. A lot of English people left in the seventies and eighties. There were some political events. But when I was growing up, English was still the main language there. Now you can’t have a sign on a store without it being either only French, or French has to be, like, twice the size of the English. And there are language police who go around and measure.

Patrick Mitchell: ‘May-sure’?

Barry Blitt: They may-sure.

Patrick Mitchell: So what made you laugh as a kid, you know, aside from your father and your brother? What kinds of things?

Barry Blitt: I can’t stress it enough: My father didn’t make me laugh. Mad magazine made me laugh and, uh …

Patrick Mitchell: … The Smothers Brothers?

Barry Blitt: The Smothers Brothers? I guess they made me laugh. What TV made me laugh? My brother and I would be sitting, you know, in front of the television for hours.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, we’re roughly the same age, so F Troop?

Barry Blitt: F Troop, I guess. That was funny. I liked Get Smart. I thought that was incredibly funny.

Patrick Mitchell: Very funny.

Barry Blitt: And there were those two superheroes. When superheroes became big, there was Captain Nice and Mr. Terrific. Do you remember those two?

Patrick Mitchell: No.

Barry Blitt: You don’t, you weren’t watching enough American TV, Pat.

Patrick Mitchell: Captain Nice?

Barry Blitt: Yeah, you look those up later.

Patrick Mitchell: I will. But no I Dream of Genie? No Green Acres?

Barry Blitt: I mean, I watched them, but I didn’t retain anything of them. There were a lot of shows that just made almost no impact. You mentioned F Troop, and I can picture all the characters and the uniforms and the arrows in the hats. But I, they really made almost no impact. I never think about Larry Storch.

Portrait of the artist as a young man: Blitt at 13, above, was featured in an article in The Montréal Star

Patrick Mitchell: The Addams Family and Get Smart were probably the truly most genuinely funny.

Barry Blitt: And The Addams Family was a New Yorker creation. You know Charles Addams.

Patrick Mitchell: So I was going to ask you, we know what made you laugh. What made you cranky, other than your old man? Where do you get your crank from?

Barry Blitt: Do you have a long weekend? Yeah, things bother me. I don’t like noise. You know, it’s mostly noise. And my brother used to—we shared a room—and my brother would snore, and that was difficult for me. And by ‘snore’ I just mean he breathed audibly. We didn’t have noise canceling headphones in those days.

What else made me cranky? I mean, you know, I had a bar mitzvah and I had to join the synagogue and I really, really loathed that. You know, I was a member of the choir and I’d have to go for practices and Hebrew school.

Patrick Mitchell: Was school rough?

Barry Blitt: I beg your pardon?

Patrick Mitchell: Was school rough? Were the kids in school difficult to deal with? Well, no, like did you have a hard time getting along in school?

Barry Blitt: I mean, I didn’t do scholastically well, but I had a lot of friends. You know, because I met the other funny kids and became friends with them. And I’m still good friends with some kids that I knew when I was five and six years old.

Patrick Mitchell: Where do you land on the Class Clown-O-Meter?

Barry Blitt: Well, I mean, what, what are the terms and the lengths? What are we talking about here?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I guess, you know, as I’m thinking about asking the question, I think a lot of confidence comes with the ability to be the class clown, right?

Barry Blitt: I got kicked out of Hebrew school. I will say that. For acting crazy. But I was quieter in public school. I wasn’t that brazen, really.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so we talked about what made you laugh and where you got your crank. Where did the creativity come from?

Barry Blitt: Geez, I don’t know. It’s like saying, “Where did the ideas come from?” It’s just, I would draw all the time and I was encouraged. I mean, my grandfather, my mother’s father, who had a blouse factory, was a Sunday painter and would copy Norman Rockwell. And he was also left-handed.

So when he saw his little grandson drawing cartoon characters with his left hand, they made a fuss over me when I was young. So positive reinforcement. And that’s probably a big part of it, but I was drawing all the time. I mean, all kids draw when they’re really young. But I guess some get made a fuss over and they continue to do it.

Patrick Mitchell: What were you drawing in those days?

Barry Blitt: Early on, Popeye. I was a Popeye freak. So I was drawing all manner of Popeye and his different characters. And Flintstones, I think I drew Flintstones off the TV. That was like, like that was a big watershed moment. I was at my grandparents’ house and I did that and there was some screaming when they saw it. And then as I got older and saw my first Mad magazine, I was copying more Drucker’s style. And not only copying, I was tracing them, too. I was excited by the visuals in Mad magazine. I attempted to draw like that for many years.

“Early on, I was a Popeye freak. So I was drawing all manner of Popeye and his different characters.”

Patrick Mitchell: And hockey players, apparently.

Barry Blitt: And hockey players. Yeah. I mean, it was a hockey household. I was late to that. I probably didn’t start following hockey until I was 11 or 12, which is pretty ancient. My father had a tremendous collection of hockey magazines, and hockey cards, and stuff. There was plenty of “scrap,” as they say. Reference to draw from.

Patrick Mitchell: But drawing hockey players actually took you somewhere.

Barry Blitt: I guess it was around that time that I started to be able to capture a likeness, more or less. And that was probably a big thing.

Patrick Mitchell: But you actually did some business drawing hockey players.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. So what I was going to say is I got a lot of encouragement as far as capturing likenesses. “Oh my God, it looks exactly like him!” It’s a lot of that sort of thing. And then I had an idea to try and meet hockey players. And I would do a drawing of, you know, say Ken Schinkel or Eddie Shack.

And when the Pittsburgh Penguins came to town, I would go to their hotel and wait in the lobby. And then all the players, you’d see them coming back from practice. And me and a friend would go up to one guy and say, “Hey, I drew your picture. Would you give me tickets for tonight?” And that became a whole thing. And then I would draw every team.

And those were my Saturdays. We’d be going downtown on the bus to the hotel where the hockey players stayed.

Blitt’s first published work—at the age of 15—was for the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins and Philadelphia Flyers, c. 1974

Patrick Mitchell: How do you grow up in Montréal, the home of one of the most legendary hockey teams ever, and become a Pittsburgh Penguins fan?

Barry Blitt: That was because of all the teams that my friends or my brother and I would pursue, the Penguins, I guess because they were, like, a nowhere team and no one knew who they were, they were just so thrilled and excited—or seemed to be—by you know, some kid drawing their pictures. And they brought me on the team bus, and they used my drawings in their program—that was about one of my first printed gigs.

I was drawing the Pittsburgh Penguins for their playoff program in, like, 1974 or 1973. And then the team went bankrupt and I was getting settlement letters for the next year. I don’t know if I ever received any money for that at all, but...

Patrick Mitchell: Have you saved any of that work?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. I’ve got that.

Patrick Mitchell: And can we see that work?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. I’ll show you (see above). Also, I had a friend in class—I don’t know what’s become of him, Freddie Bandel—who said, “I’ll be your agent.” And he wrote to every team and said, you know, “My client will illustrate your yearbook.” And the Philadelphia Flyers were happy to buy drawings at, I think, $5 each. And so I drew their whole team.

Patrick Mitchell: What was Freddie’s cut?

Barry Blitt: I don’t remember. I don’t think Freddie wound up with anything. He was just happy to have the printed stationary from the Flyers.

Patrick Mitchell: He just needed a client on his resume

Barry Blitt: I guess. I’d like to know where Freddie is now.

Patrick Mitchell: I read a quote and, and I wonder if this started in high school, you said about cartooning, “Part of it is trying to get in trouble. You’re looking where the line is and seeing how much you can step over it. And I do that in my personal life too. I try to anger and piss people off a bit to try to see what I can get away with.” Have you ever been punched in the face?

Barry Blitt: I have not been. It’s amazing that I haven’t been punched. But I’m only 65 and, you know, there’s plenty of time for that, I expect. Especially with the hostilities and tensions in the air.

Patrick Mitchell: But was that true back then too?

Barry Blitt: It probably was. I had some crazy friends—one in particular—who was just not afraid. Like, he would go over to the school bully and act crazy, and just goad him, and taunt him, and bring him this close to punching him. And it was funny as hell. And I think I learned that from my friend Andy.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so you go to college. Where’d you go?

Barry Blitt: I went to Concordia University in Montréal.

Patrick Mitchell: And studied…?

Barry Blitt: I studied illustration and I had a great teacher, Susan Hudson, who’s a wonderful artist and illustrator. But you know, at university I had to take other classes and stuff. And I had a really horrible art history class that was incredibly boring. And some English classes that were awful. I mean, I can’t remember any of my non-illustration classes there. You know, the fact that they’re not memorable…

Patrick Mitchell: They really should let you take art history, like, in your 40s when you’re actually really interested in art history.

Barry Blitt: That’s a nice idea. Like when you’re immobile. But so, after a couple of years of that—I mean, I learned a lot cause I hadn’t any art training before—I was drawing the hockey players with the big heads and the minuscule bodies without any formal art training. After going to Concordia for a couple of years, I switched to Ontario College of Art in Toronto. And was just full-time, full-bore illustration and design classes.

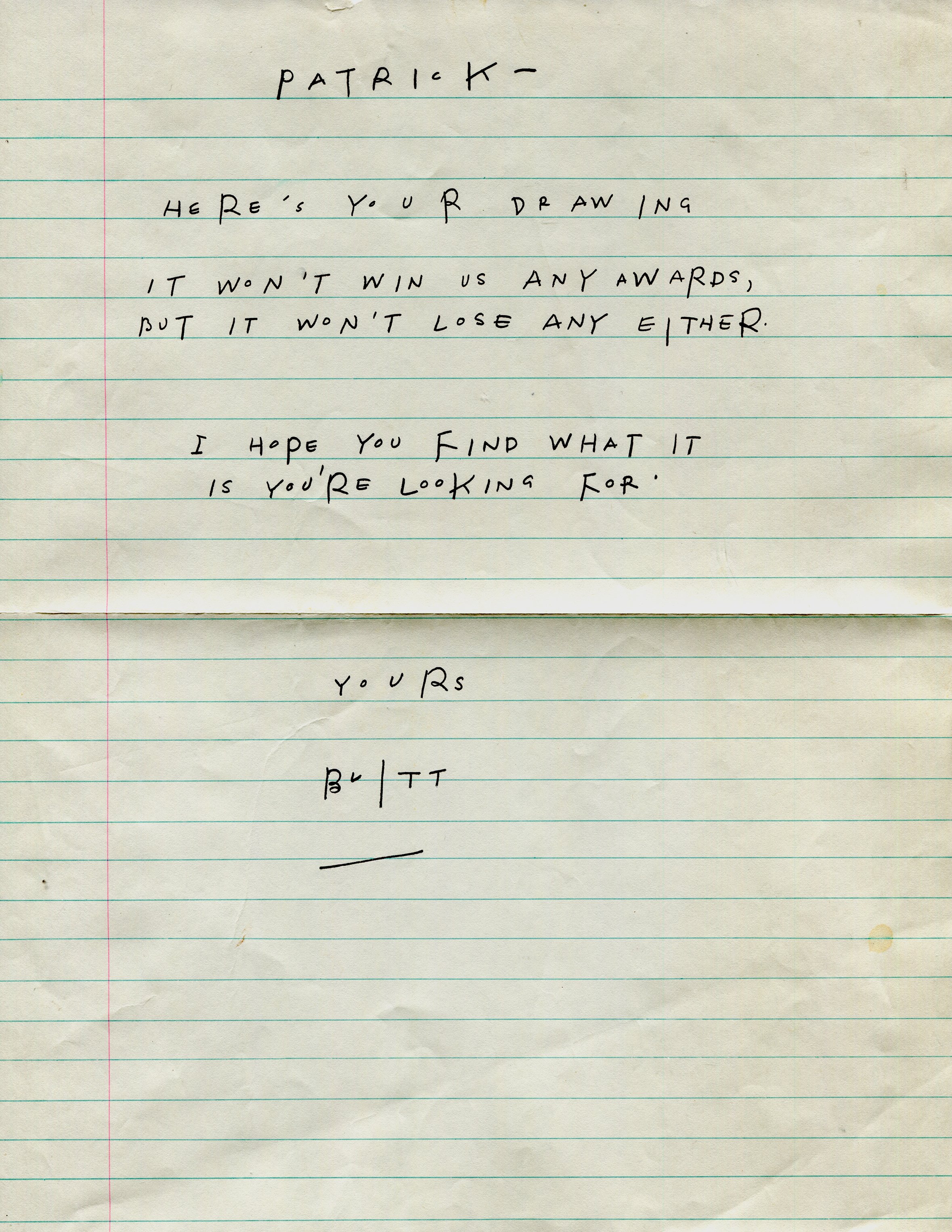

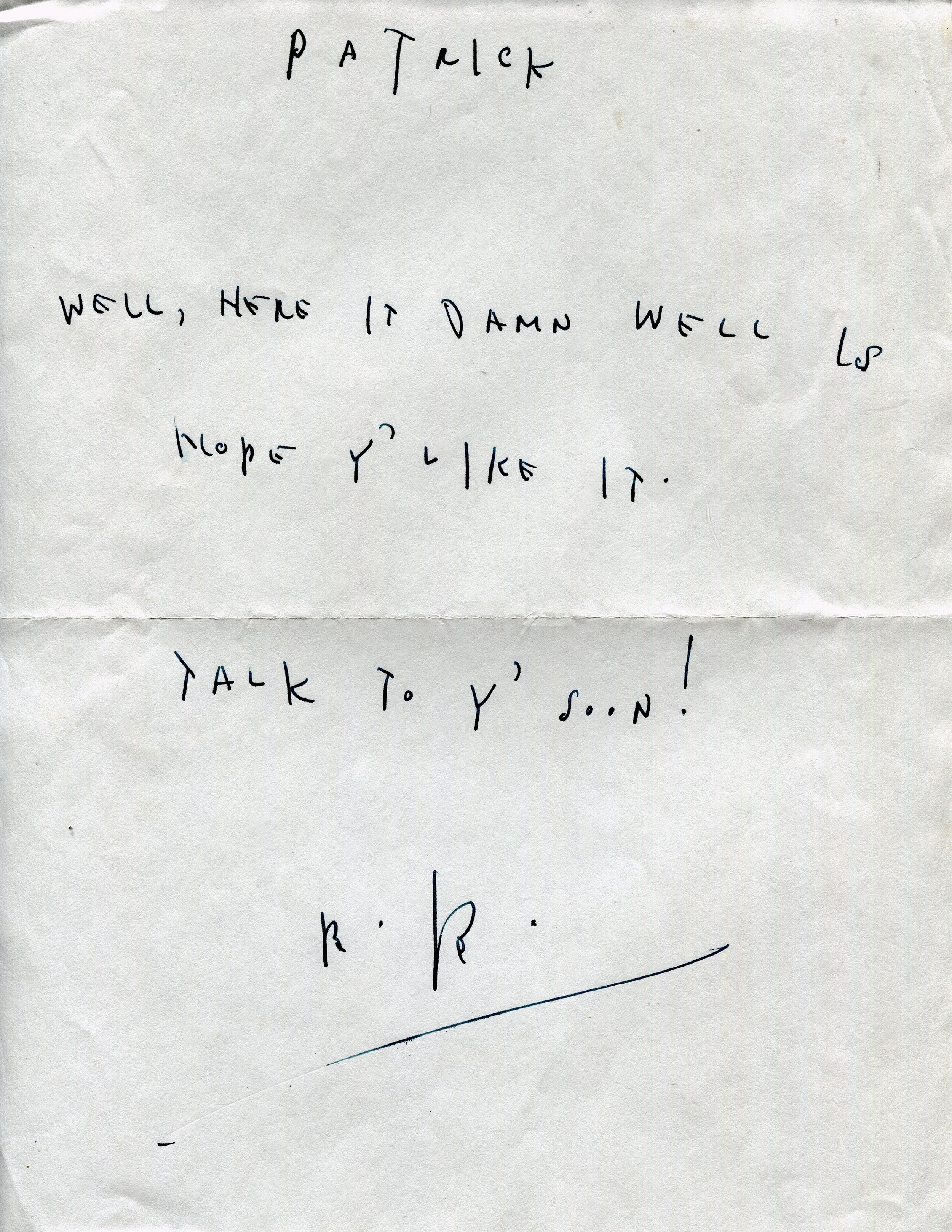

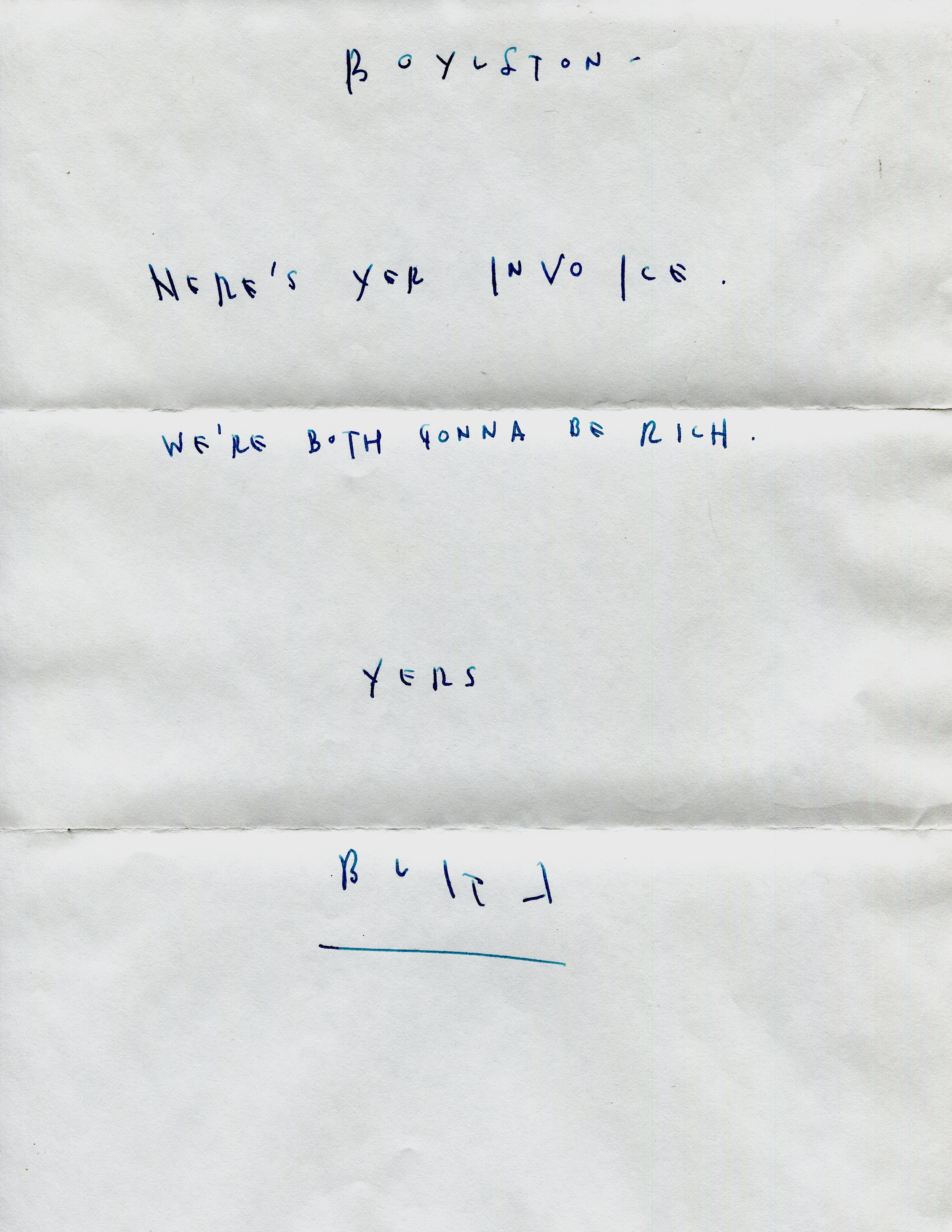

Letters from Barry

If you hired Barry, pre-email, you got a nice hand-written letter (manners, amirite?) with the artwork. I saved many of them.

Patrick Mitchell: Did your work then look anything remotely like it does now?

Barry Blitt: I mean, I made this discovery of using a pen and non-waterproof ink so that after you’ve done your line work and you put wash over it, it bleeds, which is something I still do. And I sort of found that in art school. Art school’s great for trying new things because God knows I haven’t done that in a long time.

Patrick Mitchell: Was a career plan starting to take shape?

Barry Blitt: Probably unconsciously it was. I mean, I hoped to be an illustrator. That’s what I was taking and that seemed to be a natural thing for me, considering I could draw a recognizable person. And I thought also of maybe being a caricaturist at events or something. I did that for a while too, which was bloody horrible. Jesus!

Patrick Mitchell: “I don’t look like that!”

Barry Blitt: Yeah, “That’s not my mouth!” Yeah, those were terrible. Oh my God. And I went out west at 18 and did caricatures in Alberta. In Lake Louise at a tourist hotel. And that was nice for meeting people. It was probably good for my personality, such as it is.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you put that deal together yourself or did you just show up with an easel?

Barry Blitt: No, I showed up. I had had friends who’d gone out there—it’s a real fun summer—and they’d gone out and were pot washers or elevator operators at the hotel, and I thought I would end up doing something like that. But then I walked into an art store that was at the hotel, and the lady who owned it said she was looking for a caricaturist. It was all—pretty much everything has been—a lot of luck and serendipity.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, that’s a great segue to my next question. I’m going to quote you once again.

Barry Blitt: The segues are, they’re popping here!

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. And I’m rotten with Barry Blitt quotes. Did you know there’s a page on the internet of Barry Blitt quotes?

Barry Blitt: I was not aware of that.

Patrick Mitchell: This one goes something like this: “My career path has unfolded organically, not unlike that of Forrest Gump.” And you’re already describing life just happening to you. Did you ever consider becoming a shrimp boat captain?

Barry Blitt: Well, shrimp isn’t kosher, Pat.

Patrick Mitchell: But you don’t keep kosher.

Barry Blitt: No, I don’t.

Patrick Mitchell: Come on Bubba Blitt Shrimp Company? Yeah! I could see a nationwide chain of Bubba Blitt Shrimp Companies.

Barry Blitt: Anyway, serendipity. You have to put yourself in the—I mean, I had to go out west. I had to go to Lake Louise for that to happen. But I think luck—I don’t know about you—but I think luck plays an incredibly big part of anyone’s whatever they’re doing. We’re all in a pinball machine here.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, but you did not say to yourself ever at any point “by the age of 40, I would like to be” whatever…

Barry Blitt: …Anything?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Something.

Barry Blitt: I mean, sure I did. I wanted to be an illustrator. I wanted to work for Entertainment Weekly and The New Yorker. I went to those places. And other things didn’t turn out.

Patrick Mitchell: After college, after Alberta, you went to London. What was the point behind that?

Barry Blitt: The day that art school ended at Ontario College of Art, which is now called “Ontario College of Art and Design University,” by the way. But the day that school ended, I went to London because I had got some advertising scholarship that they give out at that school. And that scholarship was to work at Leo Burnett advertising in Toronto for over the summer.

So I did that between my second and third year at school. And then when school ended, I went to London because there was so much great illustration coming out of there at that time: Ian Pollock, and Robert Mason, and Russell Mills. And Anita Kunz was actually over there too, I think, working.

Patrick Mitchell: And Ralph Steadman.

Barry Blitt: Ralph Steadman, of course. A whole bunch of others. But I ended up, after not finding any work there, I brought my portfolio around in London and nothing really happened. But I did go visit Leo Burnett over there and they offered me a job. And so I was back in advertising and had sort of a dark, mildly miserable year there not doing what I wanted to do in any case.

“Françoise Mouly encourages me not to self-edit. Send her everything. She’ll worry about whether to say no or not. It’s nice to have that.”

Patrick Mitchell: Did you go straight to Toronto after that?

Barry Blitt: Yeah, I went from there to Toronto and I really had to recover from that trip.

Patrick Mitchell: But you’re now launching a career as an illustrator?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. Trying.

Patrick Mitchell: And who was your first paying client once you got to Toronto?

Barry Blitt: Well, there was maybe Toronto Life magazine would’ve been one of them. There was Canadian Business magazine. There was the Canadian TV Guide. The Toronto Star was hiring people. And The Globe & Mail.

Patrick Mitchell: The Globe & Mail published several magazines as I recall.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. But I think they hadn’t got into the mag game yet. When I first started when I got back there, maybe in ’83, they had yet to launch Report on Business magazine, which was a magazine I ended up doing a lot of work for. But this was just still for the newspaper.

Patrick Mitchell: Saturday Night?

Barry Blitt: Saturday Night. Yeah. That was the extremely cool magazine and I don’t think they hired me. And who can blame them?

Patrick Mitchell: That’s where you met your then-wife?

Barry Blitt: My then-wife. That’s right. At Report on Business magazine. She was made the art director of that magazine, and I was already doing regular work for them. And one thing led to another. Or whatever.

Patrick Mitchell: Let’s talk about how you work with editors. And I think your collaboration with The New Yorker has been very well-documented, so maybe, you know, Barry the Illustrator, working for magazines in the traditional, get a call, get an assignment, get published sense.

Barry Blitt: Right.

Patrick Mitchell: How did those relationships work?

Barry Blitt: Well, you just reminded me. One of the first places to hire me when I did move to New York was Steven Heller at the [New York Times] Book Review, who you know is, yeah he’s great.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, that’s one of those assignments you get that’s kind of a career maker, right?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. But he was, at the beginning, just assigning really spot illustrations in the Book Review. And I remember a typical meet and greet, or going in to get an assignment, you’d wait outside, you’d be called in, he would hand you a manuscript, physically hand it to you, and say “Monday.” And then you would leave.

Patrick Mitchell: What day was it?

Barry Blitt: It was probably Thursday. I would say it was a Thursday, but it could have been a Tuesday. Or else it was like a Tuesday-ish Wednesday. In any case, you had a few days to do something.

Patrick Mitchell: I know of all the times I’ve worked with you, I’ve given you little to almost no, and mostly no direction other than, “Here’s the story.” And I don’t say “Monday.” I’ve never said “Monday.” But do you feel like you have been able to avoid those really heavy-handed kinds of processes with art directors?

Barry Blitt: Maybe with experience. But no, I’ve been in lots of those situations.

Patrick Mitchell: I mean, it feels like actually, retroactively that crankiness is a really great asset in, that your talent actually makes you desirable and your crank means “don’t fuck with me.” You know? At least that’s how I perceived it.

Barry Blitt: Yeah, I mean at some point I realized the power of saying “no.” It’s like, you can be offered work and you need work, but you just know it’s going to be trouble and it’s just easier to say “no.”

Patrick Mitchell: That’s actually one of the great secret weapons. And most people need to learn that much sooner than they do.

Barry Blitt: And I’ve also unlocked the hidden power in “maybe.” But yeah, you can say what you want about the crank, but I try to keep it to myself. Although I have done some bad things with art directors now that I think of it.

Patrick Mitchell: Barry did a bad thing.

Barry Blitt: There was a situation with The New Yorker. I don’t know if we should even talk about this, but Owen Phillips—who used to be the assistant to Chris Curry at the magazine—he was checking on this drawing he was worried about. And I don’t blame him for being worried about it because I was probably handing in crap. But he wanted to see it as I was doing it. He wanted progress shots of it.

And I said, “No, I’m not going to work that way. I’m not going to do it”

And he said, “Okay, I’ll call you first thing in the morning.” (It was due the next day). “And we’ll see how you are then.”

I said, “Please don’t do that. I don’t want you to, I don’t want to show it to you.”

And so I was up at night, worried about it, and angry about it. And I knew he would call me first thing in the morning, before I was awake.

So I left a message on my machine: “Hi, this is Barry, please fuck off after the tone.”

And of course he called at 7:30 and got that message. And he was very diplomatic about it.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, again, you know, luxury of time and perspective, we talked about your sense of humor, we talked about your crank. And those skills actually combine. Like, the humor lightens up the crank, the crank keeps the humor at bay. But strategically. And then you throw in, sort of, a skill that a lot of people don’t get until much later in life: the ability to know what’s right for you. Which, whether it sounds good or not with that art director, “this doesn’t feel comfortable to me. I know it’s going to make me miserable.” It’s understanding yourself.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. Well you’re giving me too much credit too, because I still have regular, bimonthly gigs that I just can’t stop. I don’t want to do them anymore. I know that they want me to do it, the magazines. Actually, I shouldn’t talk like that. Forget I said that.

Patrick Mitchell: So given what we were just talking about, do you ever hold back, edit yourself, either on your own or because the client said so?

Barry Blitt: I do drawings that I just assume no one will use. And sometimes I’ll put them on Facebook. Sometimes they’re, you know, too distasteful to put on Facebook, but my wonderful editor at The New Yorker, Françoise Mouly, we’ve had this conversation several times. She encourages me not to self-edit. Send her everything. She’ll worry about whether to say no or not. It’s nice to have that.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, it’s very smart on her part.

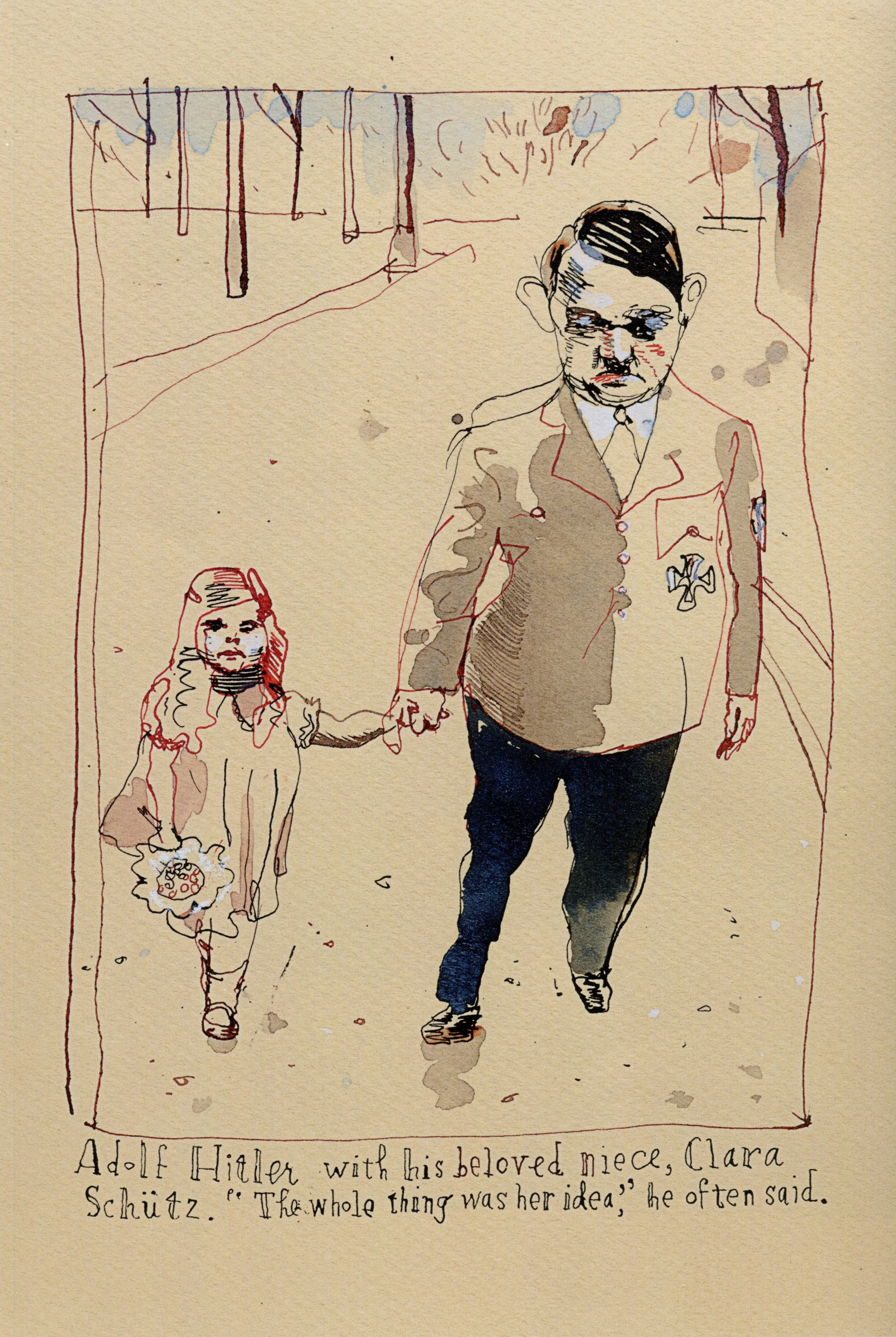

Barry Blitt: Yeah. And there’s been a couple of situations where—I did a drawing for when The Producers came to Broadway, and she sent a word to some artists about a cover about The Producers. And I did a drawing of an hysterical audience and there’s one person there, it’s Hitler. He’s sitting there. He’s not finding it funny in the audience. He’s sitting there scowling.

But I thought, you know, they aren’t going to let Hitler on the cover. So I did a patch and I covered Hitler up with an angry skinhead. And I showed it to her and she said, “Oh, isn’t this charming? But, you know, wouldn’t this work much better if it was actually Hitler himself?” And I just peeled it off. And then she, again, admonished me about self-editing.

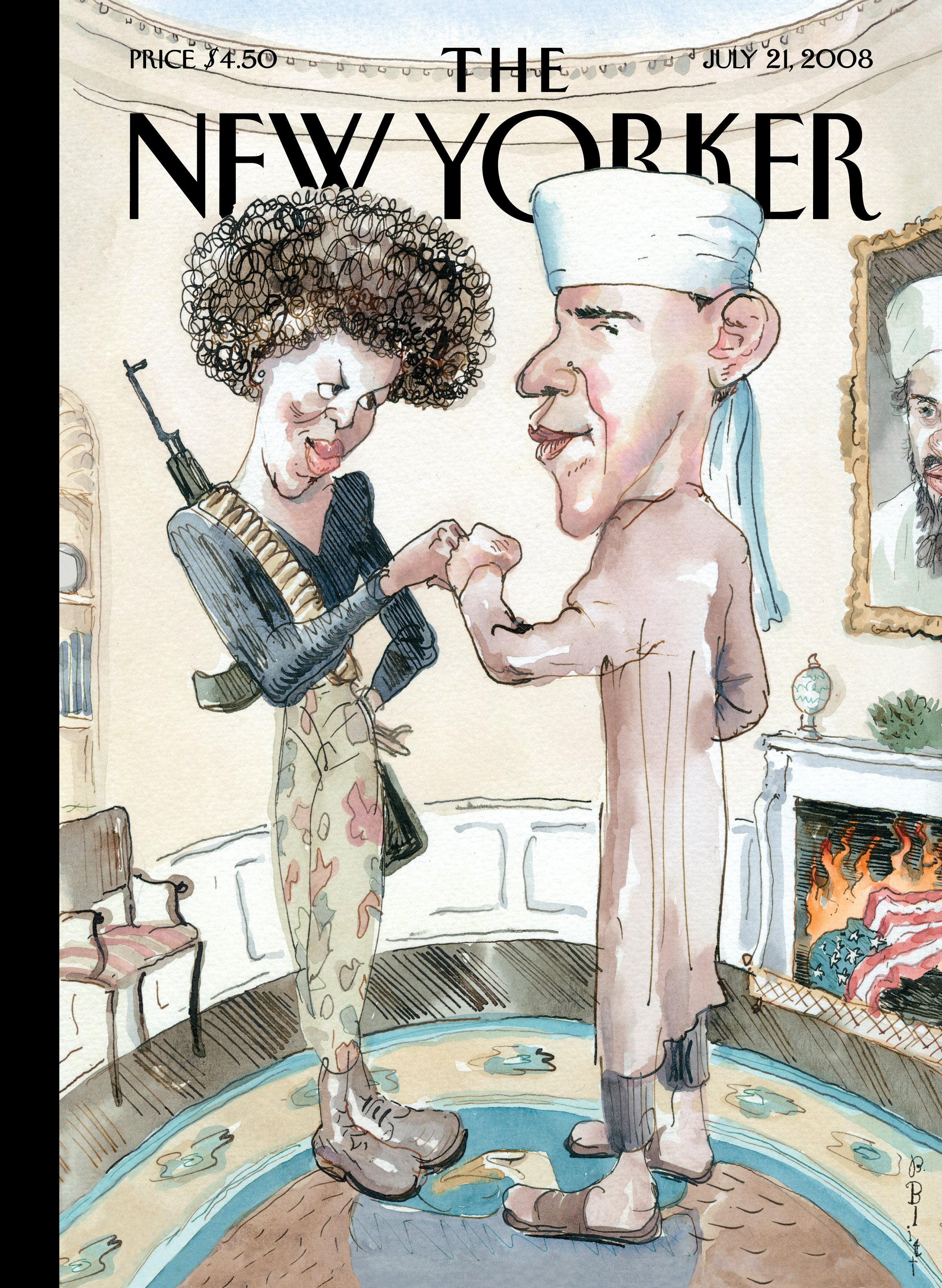

Patrick Mitchell: Well, speaking of editing, I know your Obama New Yorker cover created a lot of controversy. I mean, it may be the cover that most defines you, whether you like it or not, but talk about how that process went.

Barry Blitt: The creation of that one, you mean?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. What was the inspiration behind it, and what was the reception both at The New Yorker and out in the world?

Barry Blitt: Aw, geez. That’s a dark time. Yeah, it was the election, it was the presidential campaign of 2008. Candidate Obama was really being smeared in the media. And I remember on Fox, he and Michelle did a fist bump at some event. And they called it the “terrorist fist jab” on Fox, which seemed absurd to me. And I was still listening to a lot of Rush Limbaugh then.

And I was still fairly Canadian then, and amazed by all things American. And I did that drawing. I had sent in a bunch of ideas about the campaign and about Obama and that one, it just took all the negative stuff that was being said about him, like everything, and putting it into one drawing.

So there was a burning American flag in the fireplace, because they were saying he was “un-American” or she was un-American. And there were a lot of elements. We even talked about putting a swastika in the drawing, but we didn’t go that far. And actually the original sketch had a bunch of right wing commentators looking in through the window. You know, they were angry and aghast seeing, you know, Barack and Michelle.

Patrick Mitchell: And this sketch was it a response to a request, or was it just on your mind?

Barry Blitt: No, I think it was just something. I can’t remember if they had sent out a request for Obama images or not. It’s possible. But Obama was the big story.

Patrick Mitchell: So you send it to Françoise ...

Barry Blitt: ... sent it to Françoise, who was very entertained by it and thought it was a provocative image. And God bless her, she loves provocative images. And she showed it to David [Remnick] and he liked it too. I think she was more rah-rah about it than he was. You know, he said, “This is great, let’s do this sometime.” And she said, “This is the time right now. We’ve got to do this now.” And I was amazed too. She said, “Go ahead.”

And so I drew the thing, it was a quick turnaround. I had to bring it into town because I don’t even know if I had a scanner then, or not a good scanner. But I brought the artwork in and went up to The New Yorker office and Françoise and I looked at it and we said, “This is the image that’s going to dissolve all that crap they’re saying about him. This is going to show how ridiculous everything is.”

And we went down to the production department to give them the image to process. And the guys working there sort of looked really nervous when they saw the thing. And, that seemed to be the reaction of everybody. The magazine comes out on Monday, but it’s released to the press the day before on Sunday. I assume that’s still the deal. I’m not sure.

But yeah, I was getting phone calls from the press on Sunday evening. The Huffington Post called to ask if I regretted it. It hadn’t even hit the newsstands yet and I was being asked if I regretted it. And those next few days were very insane and frightening.

Patrick Mitchell: Was Angela Davis the model for Michelle?

Barry Blitt: Right, exactly. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: And had you considered a woman in a burka? I guess you wouldn’t recognize it as Michelle.

Barry Blitt: Actually, it’s funny you asked that, because I think that was the way she was drawn originally. In the very first sketch, they were both in burkas. But then they were saying things about her and saying she was a black panther or a radical or, I can’t remember, it was something about “kill whitey” or something. There was craziness. The country really had to go through some things.

Patrick Mitchell: But you survived.

Barry Blitt: Yeah, I survived. I think by Wednesday or Thursday things had calmed down, but it really was, it was a scandal for a few days. It was all over the world. Like, I was seeing newspapers from all over the place talking about it.

Patrick Mitchell: If you had done that in the last five years, people might have been shooting at your apartment, you know?

Barry Blitt: Yeah. And things have, yeah, it’s a whole different deal now. There are some images I’d done before that that’ve gotten me into some trouble on Twitter.

Patrick Mitchell: Did anybody send you any sort of chilling messages?

Barry Blitt: Oh yeah, absolutely. Yeah. I got some scary letters. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: Did The New Yorker get you security?

Barry Blitt: No, no. I lived in, you know, the middle of nowhere Connecticut.

Patrick Mitchell: You mean “Nebraska”?

Barry Blitt: Exactly.

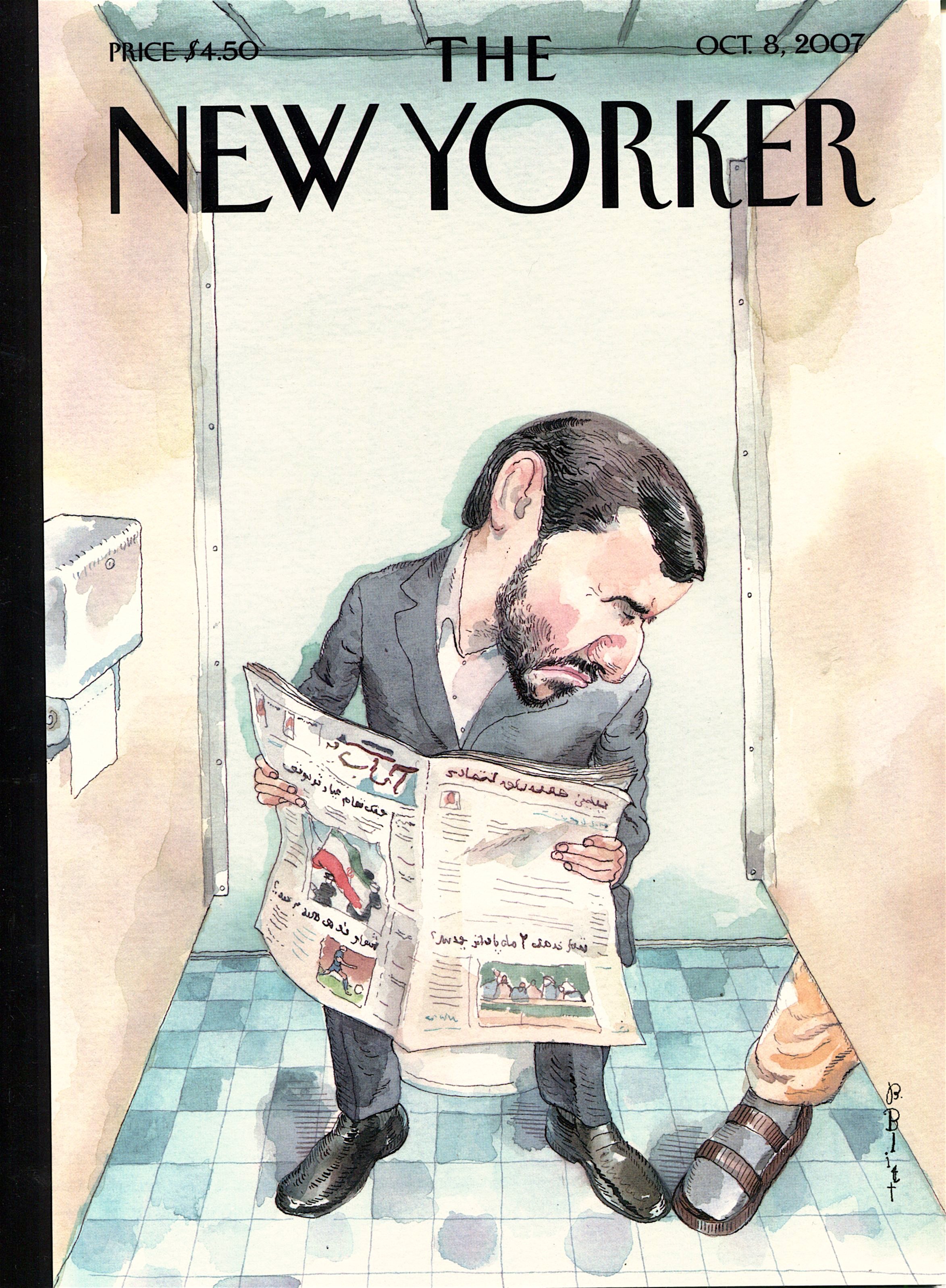

Patrick Mitchell: Well, so then, in the spirit of younger Barry, seeing how far you can push it, I think this was later, you did the [Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad cover.

Barry Blitt: Right.

Patrick Mitchell: Where he’s in a toilet stall and ...

Barry Blitt: Yeah. That was a better joke. I think that was an okay joke.

Patrick Mitchell: If people don’t remember, I think it was a thing back at that time, if you were...

Barry Blitt: ... what happened was there was a congressman, I think from North Dakota or South Dakota or Minnesota, one of those places, Larry Craig, was that his name? And he was arrested for soliciting sex in a bathroom in an airport by, what do they call it? You stick your foot under into the next stall, and that’s the way you signal that you’re “ready.”

Patrick Mitchell: Right.

Barry Blitt: Or “willing.”

Patrick Mitchell: It was a thing, I guess.

Barry Blitt: It was a thing. And it was a big news story. And right around the same time, Ahmadinejad of Iran came to the United Nations, and I don’t know what context he said it in, but he said there are no homosexuals in Iran. But it’s always nice to tie two disparate stories together. If you can make a joke out of two things that have nothing to do with each other.

And this, I don’t know, where out of the ether this idea came from, but it seemed like a funny idea to have Ahmadinejad himself aghast on the toilet as a foot was introduced underneath a stall.

Patrick Mitchell: Is there a fatwa on you?

Barry Blitt: Not that I... I probably would’ve heard.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. I can remember at least two times when you incorporated me into illustrations that I commissioned from you. Once it was for a story that we were doing about the sale of Fast Company and that made sense. But what about that other time? I can’t imagine I’m the first person you’ve done that to.

Barry Blitt: I don’t know. What is the other time?

Patrick Mitchell: You just had a character. It wasn’t about me. Just you chose to make the person in the drawing me.

Barry Blitt: Oh, right. As the devil in a, in a boardroom scene. Right?

Patrick Mitchell: Can I punch you in the face? I actually don’t remember. I just remember going, “I recognize that guy.”

Barry Blitt: Yeah, I remember that now that you mention it.

Patrick Mitchell: I thought it was hysterical, but is that the only time you’ve ever done that? It can’t be.

Barry Blitt: Drawn people into drawings? I can’t remember. It seems like something Mort Drucker would do. But I don’t know.

Patrick Mitchell: Why me?

Barry Blitt: Because you were at hand.

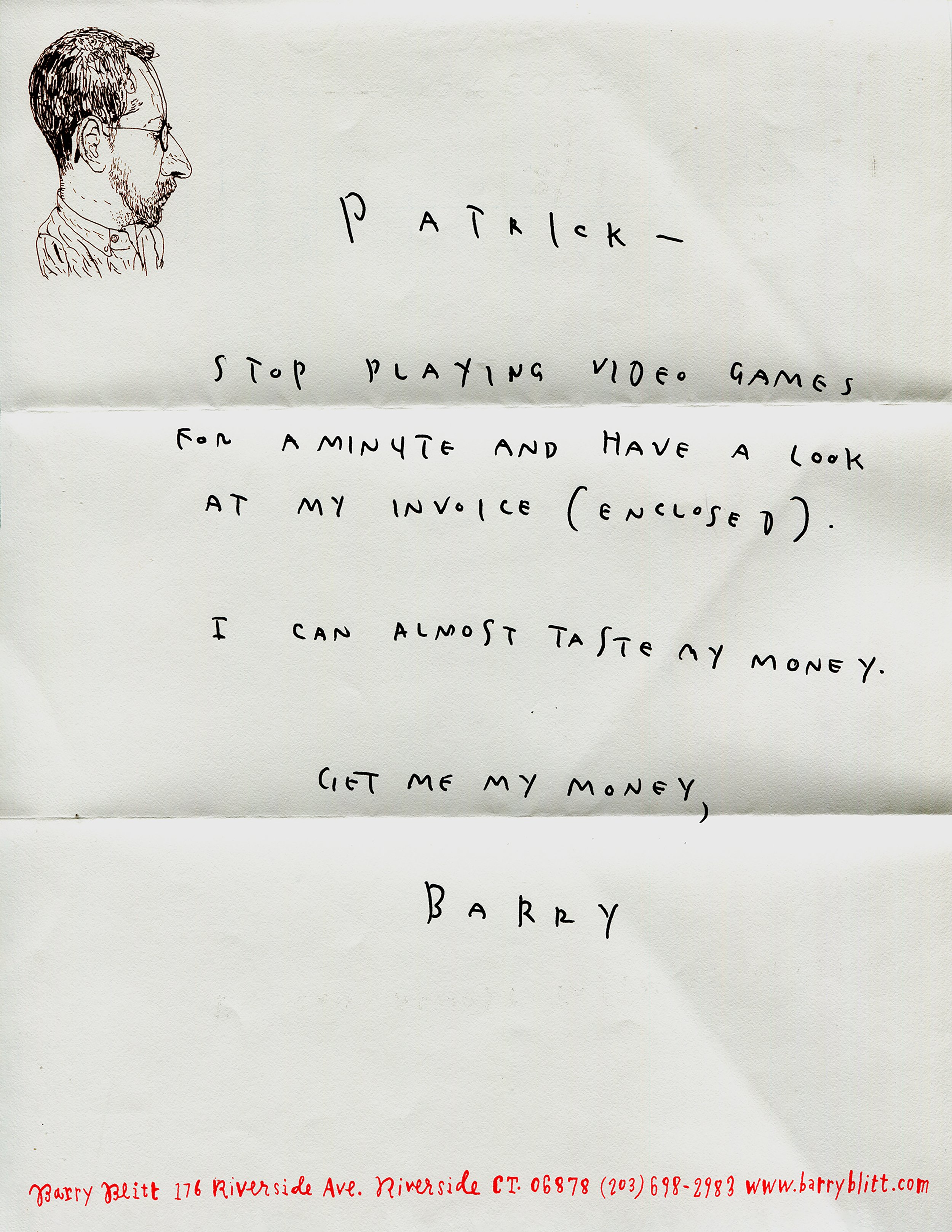

Patrick Mitchell: Let’s talk about money. How much do you get paid?

Barry Blitt: For what? I’m doing a lot of online stuff now and it pays much worse.

Patrick Mitchell: No, no. I don’t really want to know. That’s tacky. Plus, I saw you bite some lady’s head off for asking you that at an event. This is just a set-up to introduce and share a “special treat” with our listeners. But about 30 years ago, this was your answer:

Barry Blitt (in 1998): “Uh, $4500.”

Patrick Mitchell: Here’s the story: You had done work for a Fast Company feature. And, apparently, we were delinquent in paying for it. So one day, I come back to my office from lunch and there’s a voicemail waiting for me. I pick up the phone, and all I hear is piano. Kind of a ragtime riff. And then the voice of Barry Blitt, singing:

Oh, Faaaaaast Company,

Faaaaaast Company.

But they ain’t too fast

when it comes to paying me.

And then you said, “Where’s my check?” And hung up. But your message went viral. All day, my coworkers were popping in and out of my office: “Play the invoice song! Play the invoice song!”

Later, when you and I talked, I suggested upping the ante next time. I wanted a video invoice.

Barry Blitt: Oh, no kidding. That’s how that happened? It was your idea?

Patrick Mitchell: And did you pass on that opportunity?

Barry Blitt: No, I didn’t. I made you a video invoice (see below).

Patrick Mitchell: It’s a special treat. A piece of magazine history. I highly recommend checking out the dusted-off and digitally-remastered Video Invoice #3127, ©1998 in all its VHS glory, along with the full-length featurette, The Making of Video Invoice #3127, with cast and crew interviews, outtakes, dramatic behind-the-scenes revelations—the whole thing.

Barry Blitt: Let me just say that I think that’s a mistake, but you do what you have to do. You’re the art director.

Video Invoice #3127

Patrick Mitchell: But seriously, I don’t really want to know about your income. Clearly you’ve made a nice life as an illustrator. I guess the reason I ask—this has been something that’s been on my mind for 40 years. I remember once talking to an illustrator, not you, and in the course of the conversation they said something about their vacation house.

Barry Blitt: Ah.

Patrick Mitchell: And the narrative in our business has always been that illustrators get paid little-to-nothing and their work takes weeks to produce. So that math never made sense to me, about illustrators and vacation houses, and yet it’s somewhat rampant.

Barry Blitt: Vacation houses for illustrators? It’s rampant?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I’m surprised at how many times I’ve heard illustrators talking about their summer house, or something like that.

Barry Blitt: Well, maybe these people came from money which allowed them to pursue a poor paying job like Illustrator.

Patrick Mitchell: I think the actual truth is an illustrator can do 40 illustrations in a day.

Barry Blitt: Oh, it depends on the illustrator. Some people put actual time into them. I’m lucky that my style, such as it is, you know, I’ll do a drawing once and if it turns out okay, if I can live with it being published, then I’ll hand it in. But usually, I know I can do it better. I try it again. The first one was better. I do a third one. I like the second one better. I ended up doing a drawing as many times as there is until the deadline.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I guess digital changed everything too, because I remember, again back at Fast Company, hiring Paul Davis. He worked in oil, and he had to do a quick turnaround piece for us. And over the weekend, he shipped it and it was in this big box that had been built with wood to separate the packaging from the painting to protect the wet oil paint.

But let me ask you this: what is the most you’ve ever been paid for an editorial job? You don’t have to say what it was or who it was.

Barry Blitt: The most I’ve ever been paid for a—really? You want me to say?

Patrick Mitchell: What’s the biggest invoice you’ve ever sent for an editorial job?

Barry Blitt: I remember I did a gatefold thing for Sports Illustrated. That was a job I would never take unless it was some kind of incentive, like money, because it was a big pool scene with all these celebrities, you know, some were swimming, some were eating, some were sunbathing. It’s the kind of thing I hate to do and it’s low reward, except for any payday. And I think it paid maybe $18,000 or something. But maybe I have that completely wrong. I don’t know.

Patrick Mitchell: No, that sounds about right.

Barry Blitt: And I can’t imagine I was ever paid more than that for anything. I mean, The New Yorker, they have a deal where they sell prints of your covers, of the artwork you do. So every month you get a check. Sometimes it’s for a real pitance. In my case anyway.

Patrick Mitchell: But like, The New Yorker is a good example. You’re a regular contributor. You’ve done what, hundreds of covers, right? Over a hundred?

Barry Blitt: Over a hundred. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: But yet they still pay you as a contributor? Like, you’re not on any sort of retainer.

Barry Blitt: I’m not on staff, no. But I have a contract.

Patrick Mitchell: Oh, and so, loosely, what are your requirements?

Barry Blitt: The contract is just that if you do a cover and then you do another one in the calendar year, you get a bit more, incrementally more. But then it starts again at the beginning of the year.

Patrick Mitchell: Is there any language preventing you from working for competitors?

Barry Blitt: There is, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: And who are their competitors? The Atlantic?

Barry Blitt: Is The Atlantic one? I mean, they don’t call so, I don’t know. The New York Times Magazine and New York magazine. I think those two.

Patrick Mitchell: And in the last couple years, you’ve started working for Air Mail Weekly.

Barry Blitt: Air Mail Weekly. Yes. Air Mail.

Patrick Mitchell: Is that a good deal for you?

Barry Blitt: Well, I’m delighted with the gig. I’m happy to have the gig. And it’s nice to work for Graydon [Carter] again. I worked for him at Spy, and at the New York Observer, and at Vanity Fair.

And now at Air Mail, this lovely online magazine he started. After he left Spy and went to New York Observer—I had worked for him at Spy and he called me to do something at The Observer. And I was excited that he remembered me and wanted me to do something for his new gig. And he asked me for a portrait of someone.

I said, “How big should I make it?”

And he said, “Make it the size of a softball.”

Patrick Mitchell: But I know in talking to you in preparation for this thing for weeks, that there are a couple days a week that are really crazy for you, and I assume that’s around Air Mail.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. And my Air Mail deadline is today and I do something online for The New Yorker called “The Kvetch Book,” and that’s just a weekly online drawing. And that’s also a Thursday deadline. I don’t know how I’ve managed to have both those days be the same deadline.

Patrick Mitchell: And how are we doing for today?

Barry Blitt: Today we’re doing okay. I did a drawing that almost made sense for The New Yorker. And for Air Mail, I got a call yesterday from the art director saying, “Oh, by the way, our theme of this issue is south of France.” So I was able to do a Rudy Giuliani face down on the beach in the south of France for that. So I handed that in.

Patrick Mitchell: So we’re good.

Barry Blitt: We’re more or less good, yeah. There’s still some wrangling, but yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: I asked you this about when you were young. What makes you laugh now? What’s funny to you? TV, books, magazines, the world, neighbors. Who really cracks you up? Or can you be cracked up at this age?

Barry Blitt: Yes, I can absolutely be cracked up. I’ve been watching the five seasons of Louis CK’s TV show.

Patrick Mitchell: Are we allowed to laugh at Louis CK?

Barry Blitt: I think we are. Yeah. I mean, some of it, there are certain jokes he’s made that in light of the last few years are really cringeworthy. And the Cohen brothers crack me up. And many cartoonists and illustrators crack me up. You know, Anne Telnæs and John Cuneo crack me up. And Ross McDonald cracks me up. It’s too big a list. Curb Your Enthusiasm cracks me up, no matter how many times I see it.

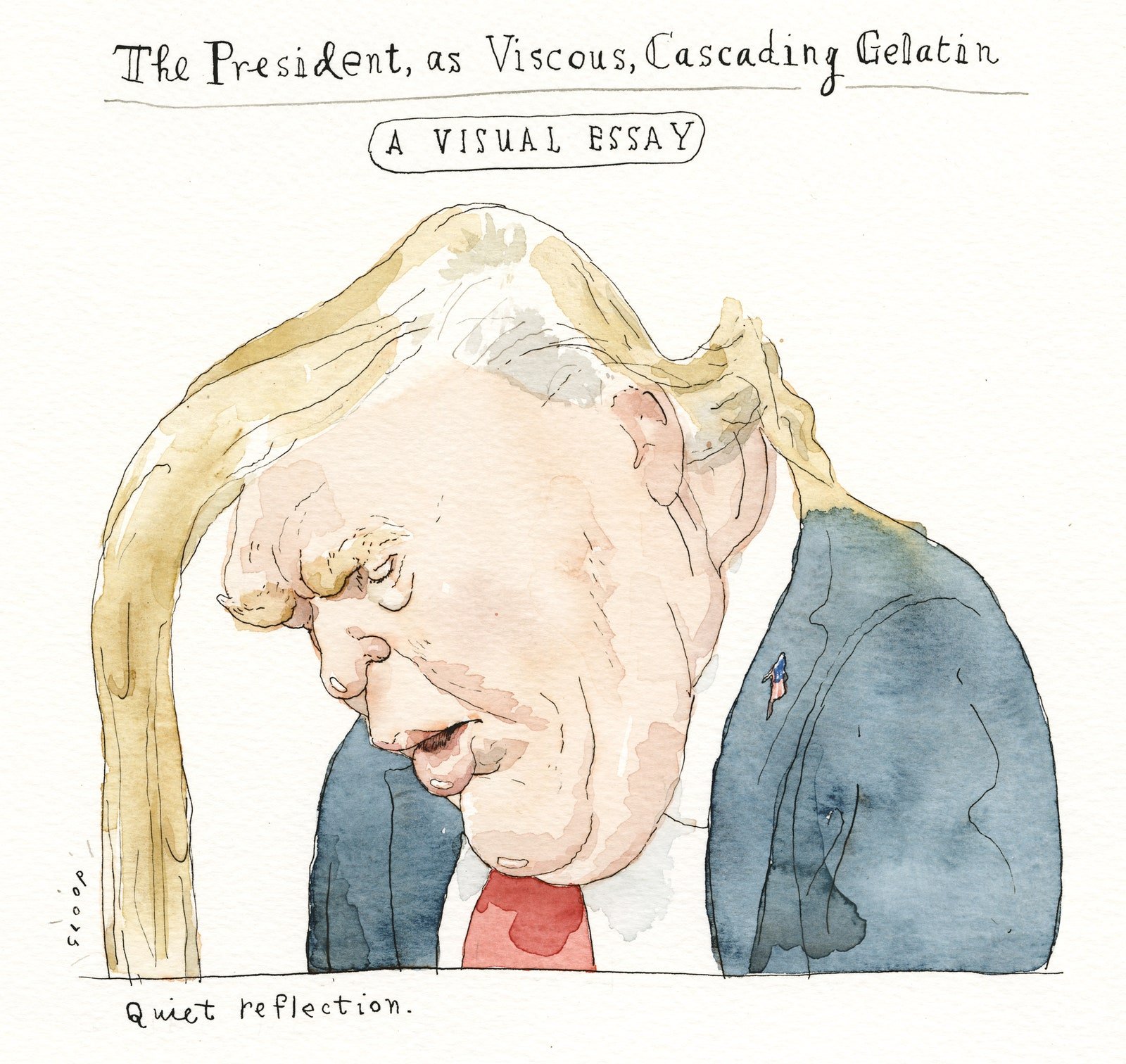

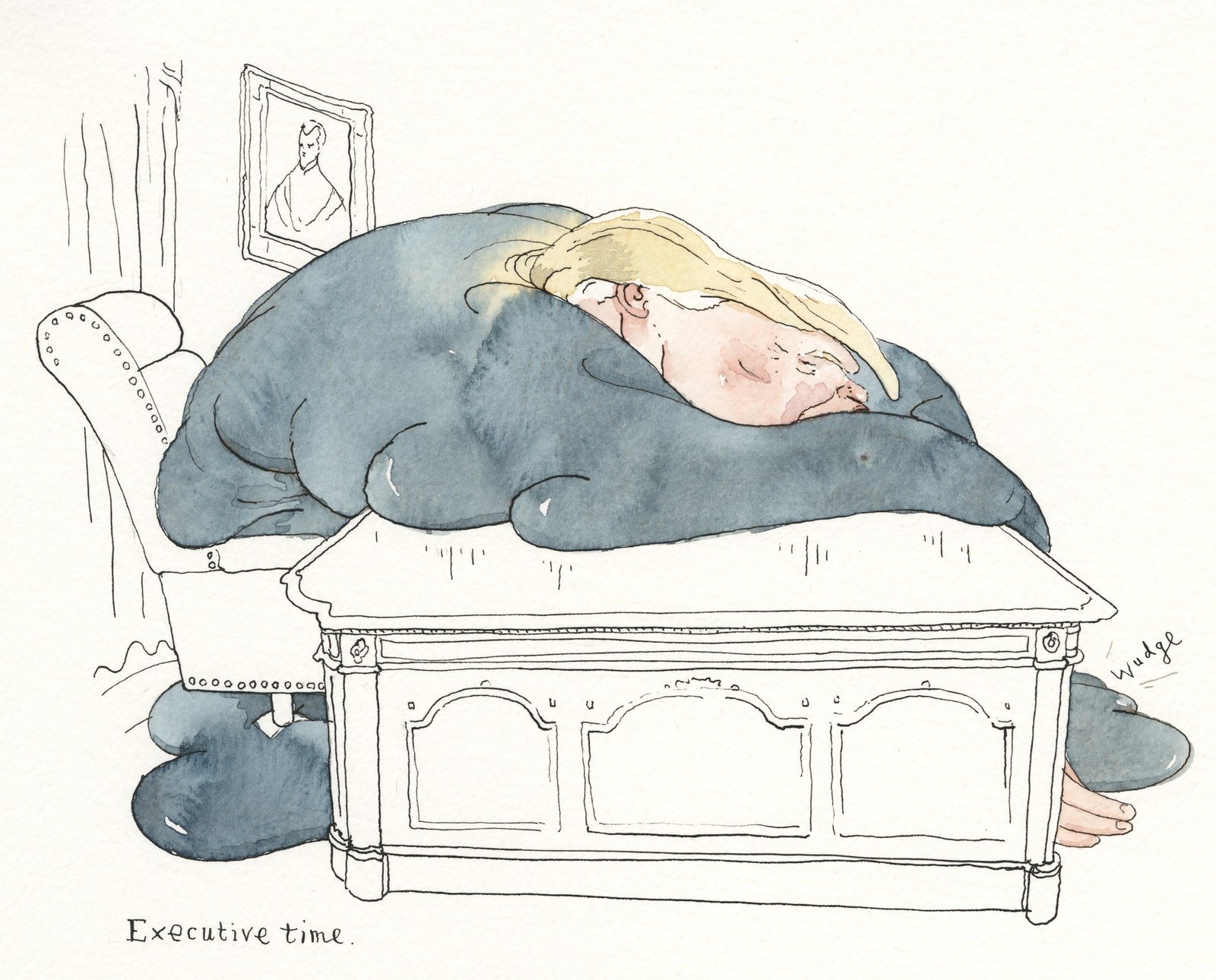

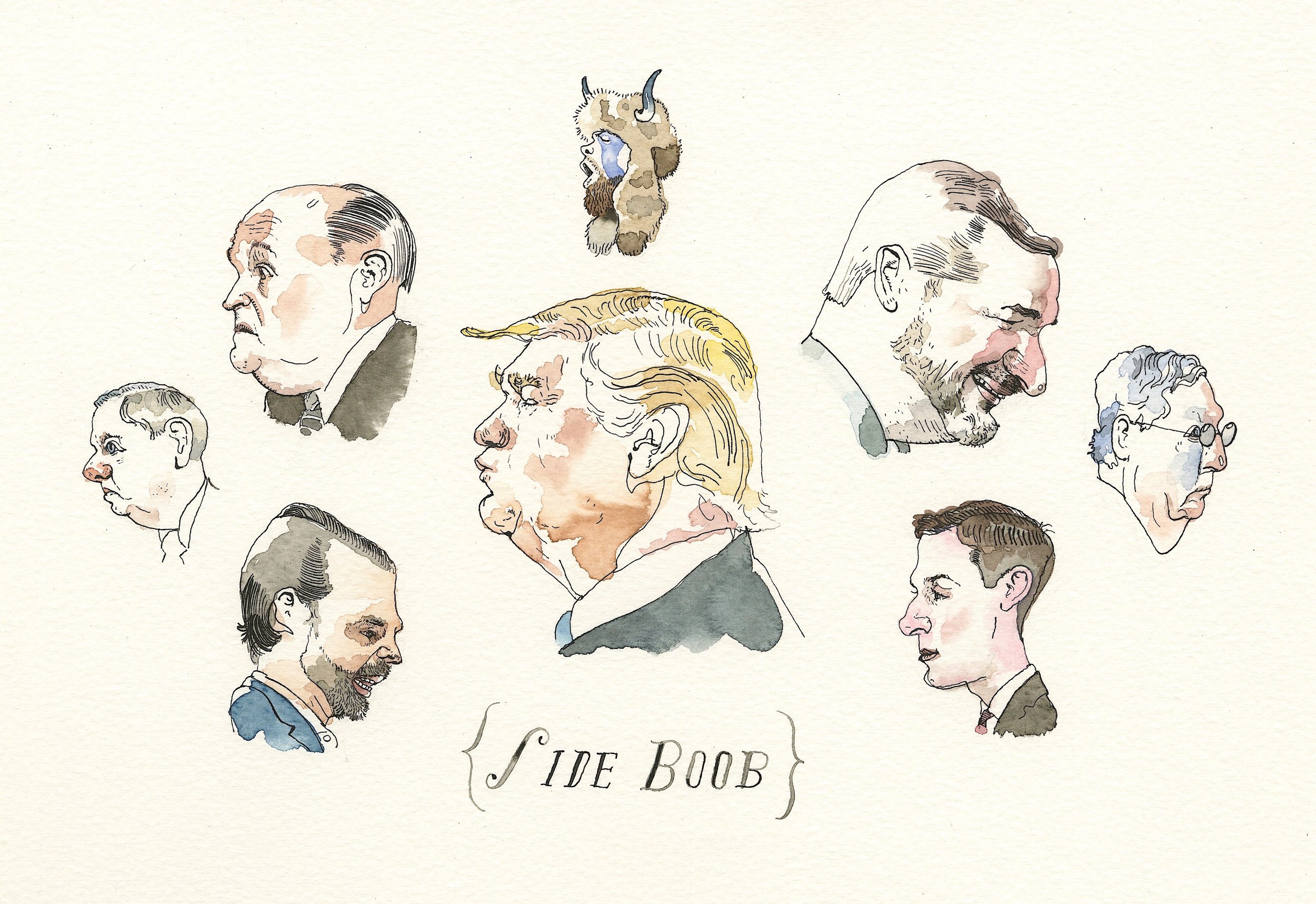

In the Matter of Blitt v. Trump

Patrick Mitchell: Speaking of Ann [Telnæs], I wanted to share this quote of yours on Trump. It makes me laugh. You said, “He’s sculpted out of some kind of pudding. I think it looks like his face is sort of melting, slowly.” But I want to ask you, so you’ve spent a good portion of the past decade, unfortunately, thinking about Trump, drawing Trump, and so I have two questions. It can’t be healthy having that much Trump in your life.

Barry Blitt: It’s not, it really isn’t. And it’s corrosive. And I’m glad this interview is only audio and not visual, because it’s not done me any good.

Patrick Mitchell: But there’s nothing you can do about it, right? You’re obligated.

Barry Blitt: I could do other things. But I still have the need when doing cartoons for a publication to be topical, you know? I have done stuff that wasn’t topical and you always feel a little bit better after that somehow.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, you do. And that actually gets to my second question because. I mean, you do probably, but I do too. And this is as much an observation as a question from someone who, in a very unhealthy way, allows Trump and cable news—I’m talking about myself now—this cable news mess that follows him occupy too much of my time.

I’ve wanted a politician, or a pundit, or an expert to clarify things, to make things make sense, to make me feel better about the world. And after spending so much time over the past couple weeks researching you and looking at your work, I almost feel like—this is sort of a revelation—that you and some of your contemporaries, your work may actually be the answer.

Because you can say what needs to be said without saying it. At least not spelling it out in words. It’s just the style of your drawing, the innuendo, and the, sort of, metaphor that you bring into it. I’ve just found it, in a lot of cases, where that was the answer I was looking for, that nobody talking at me can give me.

“If Trump’s president again, I can’t believe I will stay here.”

Barry Blitt: Do you watch political TV? Do you watch the news much?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Too much. I have friends who worry about me. And I had to get off Facebook because the first four years of Trump, I vented so vehemently on Facebook that I just had to get off of it.

Barry Blitt: I don’t watch any political TV. If there’s a—if Trump, if an indictment is announced, you know, I might run to the TV for that 15 minutes or something. But generally, I don’t. Because it is...

Patrick Mitchell: Well talk about that because I think you can help me and maybe a lot of other people who—you know, we’re in a business where we’re sort of programmed to be aware, and to read, and to listen—but I know, intellectually, that cable news is not necessarily the most informative.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. It’s not even informative. But I just don’t like someone talking at me. And it seems like Fox started it. I don’t know if they did, but it’s really become so divisive and so polarized. It’s just no fun. I don’t even like to hear the things that I believe shouted back at me stridently by some clown on TV.

But unfortunately, I’m not immune here. I’ve sort of got hooked on Twitter, and I’m finding that really unhealthy. I’m going to have to stop doing that.

Patrick Mitchell: But again, because it’s a requirement of your job, you feel like you can be well informed without those things?

Barry Blitt: Without TV? Absolutely.

Patrick Mitchell: And so where do you turn?

Barry Blitt: There’s lots of news aggregation sites. There’s Memorandum, which has both left and right. And there’s Twitter. And there’s Drudge, which has become much less right wing than it used to be. And The Washington Post and the Times. And, I mean, I’ll even go to Breitbart sometimes if I can stand it. But it’s important to flip around.

Blitt accepts the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning from Columbia University President Lee Bollinger. (Jose Lopez/The Pulitzer Prizes)

Patrick Mitchell: All right. Here’s a series of—it just feels so cliché to call them “rapid fire”—but I’m going to throw some things out at you and just ask your thoughts on them. And the first one is: Cartoonist.

And the reason it’s in this list is because in all my research, I’ve always found it jarring when people refer to you as a cartoonist. Because since day one, I’ve always known you as an illustrator. But does that matter to you? Is there a difference? And what do you call yourself?

Barry Blitt: I call myself “Daddy Sir.”

Yeah, I never thought of myself as a cartoonist, really. And certainly I set out to be an illustrator. At Entertainment Weekly, though for some reason I got asked to do a half page cartoon about something and ended up doing that regularly.

But even then, it still felt more like an illustration gig, even though I was getting to write little captions—sort of jokes.

Patrick Mitchell: And yet you won a Pulitzer Prize as a cartoonist.

Barry Blitt: Yeah, that’s many years later yet. I mean, I was doing these weekly cartoons for Entertainment Weekly, I guess they were cartoons, and then Bill Clinton got in trouble with Monica Lewinsky and suddenly that became pop culture. Everyone was covering that. I mean, I don’t think the first George Bush was being...

Patrick Mitchell: ...was cleaning up his DNA?

Barry Blitt: No. Although he did throw up on the Japanese prime minister, I think. But that’s another story. But with Bill Clinton, suddenly I was getting asked to draw him for Entertainment Weekly in those cartoons I was doing and from The New Yorker as well. And, yeah, after a while I sort of fell into that in a way.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, are you actually doing any commissioned illustration anymore?

Barry Blitt: Sure. Mm-hmm. I mean, there’s not much around, but I’m doing some, yeah. Absolutely.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, speaking of the Pulitzer Prize, the next thing is: Short Pants.

Barry Blitt: Yes. My wife bought me a pair of—I wanted comfortable pants because really comfort is the most important thing at this age. Or really at any age. And these, sort of, yoga-type, kind of loose fitting pants that end just above your ankle...

Patrick Mitchell: …Clam diggers?

Barry Blitt: Maybe even a little higher. Is that what they’re called? Clam diggers? I thought maybe they were...

Patrick Mitchell: Capri pants!

Barry Blitt: Maybe they’re Capri pants! Let’s call them Capri pants. Yeah, I was wearing them all the time and that’s become a thing.

Patrick Mitchell: Safe to say that you were the only person in Capri pants at the Pulitzer ceremony?

Barry Blitt: Certainly the only male. Yeah. I dressed funny for that. But I had a nice white blazer.

Patrick Mitchell: And an incredible hat.

Barry Blitt: Did you see a picture of it or what?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, there’s a picture of you accepting your award…

Barry Blitt: Ah, okay.

Patrick Mitchell: …In your short pants.

Barry Blitt: Right. I see. Good laugh at that?

Jell-O shots with the (ex) President

Patrick Mitchell: To this day. All right: Canada.

Barry Blitt: Canada, yeah. Like Neil Young and, and Barbara Streisand. Is she Canadian?

Patrick Mitchell: No.

Barry Blitt: Sorry, let’s start this again. Canada.

Patrick Mitchell: Celine Dion.

Barry Blitt: Celine Dion, right? Yeah. She can’t sing anymore, apparently.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you miss it?

Barry Blitt: Canada? Do I Miss Canada?

Patrick Mitchell: Or Celine Dion’s singing. Either. You can take either one.

Barry Blitt: I’m going to answer your second question first. Sure I miss Canada. I miss my friends in Canada. And I miss my youth in Canada. My mom’s still there. And, uh, I love Canada. I have a feeling I’ll end up living there again. Especially if things get much uglier. I mean, if Trump’s president again, I can’t believe I will stay here.

Patrick Mitchell: So my next one is: Citizenship. Did you retain both?

Barry Blitt: I did retain both. I was recently told that you couldn’t always do that, and it’s a relatively recent thing. I was sort of surprised to hear that, that it was in the eighties or nineties.

Patrick Mitchell: What was behind getting citizenship?

Barry Blitt: What was behind citizenship is that my wife had moved down from Toronto and we got married and I was able to give her a green card as long as I was a citizen And it was time.

Patrick Mitchell: So it was for practical purposes.

Barry Blitt: It was practical and it, well, yeah. Why else does one become a citizen?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, you don’t well up when the “National Anthem” plays.

Barry Blitt: Well, I’ll tell you, I don’t well up when the “National Anthem” plays, although if it’s a moving rendition of it I might. And Angie makes fun of me when we went to the ceremony and I became an American citizen. I was surprisingly a little bit moved by it and wasn’t cracking a lot of jokes. And was repelling her jokes.

Patrick Mitchell: Zarley Zalapski.

Barry Blitt: Zarley Zalapski was traded to the Hartford Whalers by the Pittsburgh Penguins. He was a defenseman. He was traded right before the Penguins won their first Cup. So I guess that would’ve been 1990. Yeah, they traded him and got Ron Francis and Ulf Samuelsson in return. That was a great trade.

Patrick Mitchell: I only ask that because I remember, years ago, I was a big sports card collector, and periodically hockey cards would show up. And I did get a Zarley Zalapski and I saved it because it was the least-sporty name of an athlete you could come up with. And when I found out that you were a big Penguins fan, I faxed you my Zarley Zalapski card.

Barry Blitt: I like when people used to fax images. Sometimes the New York Observer at the very last minute when I would do portraits for them, they would fax me like a person to draw and you couldn’t tell if they had a mustache or if it was the back of their head. It was very, very bad resolution.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay: The Half-Tones.

Barry Blitt: The Half-Tones was a jazz band of all illustrators that I became part of, well, I don’t know how many years ago that was probably 15 years ago maybe. Or, and it was Joe Ciardello and Michael Sloan and Robert Saunders and James Steinberg and Richard Goldberg and Hal Mayforth. If I’m forgetting anyone, it’s only because I’m old. But that was a wonderful thing.

Patrick Mitchell: When was the last time you played?

Barry Blitt: The last time we played, I mean, everyone’s moved far apart and there was the pandemic and it’s been a while. A smaller group of us with an actual guitarist who was a non-illustrator—as eccentric as that is—we had a Half-Tones II group: Ciardello, Sloan, me, and Chris Mariner, who's an actual musician. And that was really, it was really fun to get together with those guys and play music.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you get a chance these days to play with other people?

Barry Blitt: Not as much. As I mentioned my hermitude. I’m mostly just sitting in my room, you know, playing the same song over and over again.

“I’ll do a drawing once and if it turns out okay, if I can live with it being published. But usually, I know I can do it better. I try it again. The first one was better. I do a third one. I like the second one better. I ended up doing a drawing as many times as there is until the deadline.”

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. All right, back to the rapid fire: Weed.

Barry Blitt: Weed. That’s part of a healthy diet. I think it’s FDA approved. And I think for generating ideas, I mean, if you’re seriously asking me, I think it helps now and then. For me, just speaking for myself, if I’m leaning on it every day of the week, it sort of stops. It nullifies itself. But once in a while, it’s a great kick in the ass.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I was speaking to a very trusted friend recently, having an intellectual discussion about edibles. And she made a compelling case for giving it a try. I mean, there’s a lot of negatives with alcohol and if you’re looking to get mellow, you might seek alternative routes.

Barry Blitt: That doesn’t make me mellow at all.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I talked to our mutual friend, who’s had some experience with this and the question really became, what do you want out of it? And under what circumstances would you want to do it? And so, for our weed curious listeners, any recommendations? And do you take edibles?

Barry Blitt: Sure, yeah. I know someone who makes marijuana sugar, which is great. I mean, if you’re asking me why I use it, I think ...

Patrick Mitchell: Well, yeah. There’s a lot of questions like does it help you be more creative?

Barry Blitt: The only reason I use it is, it’s sometimes good for work. And sometimes it’s disastrous for work. You get a ton of ideas, because it does tend to focus you—probably like Ritalin does—and you’re making yourself laugh, and scribbling stuff. And then you look at it later, and sometimes it’s crap. And not just sometimes. But it does get a lot of stuff on paper and I find it good for generating creative energy.

Patrick Mitchell: Well hopefully we’ll get some weed sponsors for the podcast. All right, moving on: Françoise Mouly.

Barry Blitt: Yes. Françoise is a person dear to my heart. Someone I’ve worked with for a really long time. I guess it might be the longest working relationship I’ve had. And, she’s just, her instincts are great. There’s so often she’ll see something in a drawing and say, “That doesn’t work.”

And I disagree with her with every creative instinct I have. And then, of course she was right afterwards. That seems to be the rule. It’s always like that. But she’s wonderful to work with and has a great spirit for provocative stuff and for saying the right thing in the work.

A Covid-era piece for Air Mail

Patrick Mitchell: People tend to stay at The New Yorker for a very long time.

Barry Blitt: Some do, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: How long has she been there?

Barry Blitt: Well, the first time I met her, I had gotten to know Chris Curry a little bit, as I told you, I had an interview with her, and Françoise wasn’t there yet. And then when Françoise started working there, Chris kindly brought me over to Françoise’ office and introduced me to her.

And I went in and talked to Françoise for a little bit and I didn’t realize I was sitting in her chair. But she didn’t say anything because that kind of stuff doesn’t bother her.

Patrick Mitchell: It was a “meet cute.”

Barry Blitt: It was. It really was a meet cute.

Patrick Mitchell: So she’s been there 25 or so years.

Barry Blitt: Yeah, this was ’93, so that’s close to 30, I think.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s a miracle in this business! Okay: Edel Rodriguez’s Trump work.

Barry Blitt: I love Edel Rodriguez’s Trump work. And I think the thing mostly that’s remarkable about it is that it’s what they say art should do. He sort of created his own visual language around Trump. There’s lots of people drawing Trump’s caricature in any way you can think of.

But he’s created this, you know, monochromatic, or at least flat-colored, template. And, immediately, it’s recognizable. And he is able to program so many ideas into that particular style. So I’m sort of in awe of that.

Patrick Mitchell: I haven’t seen anybody accomplish anything like that with what he’s done with Trump. And it’s not just Time magazine. It’s all over the place.

Barry Blitt: Right. Der Spiegel.

Patrick Mitchell: We should also give a shout out to your friend at The Washington Post who you mentioned to me. I checked out her work and it really is amazing.

Barry Blitt: Ann Telnæs.

Patrick Mitchell: So people check out Ann Telnæs.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. She’s a great caricaturist. And an animator as well. And her ideas are hilarious.

Patrick Mitchell: As is her Trump. Next: Deadlines.

Barry Blitt: Well, all I can say is if you add another “s” to deadlines, it’s “deadliness.” Ah, deadlines. Yeah. It’s fun to, sometimes, when we talk about pushing the line and stepping over the line, I’m afraid I’ve had some trouble with deadlines. I once made an art director at Time magazine cry because I was late with something and I’m not sure why I would mention that now. Yeah.

Deadlines are hard. Often, like, I’ll have a drawing and it’s finished, but I know I can do it better. Think I can do it better. And the deadline comes and goes and I’m still working on another version of it. And really, in retrospect, I would’ve been better off just making the deadline and stopping myself.

Patrick Mitchell: We’re in the digital age now, but I feel like either you mentioned or—we’ve all done this, at some point, had to drive work somewhere.

Barry Blitt: Oh, geez. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: What’s the farthest you’ve gone to deliver?

Barry Blitt: I’ve gone to the airport, I mean, I didn’t drive a car until much later in life. I’ve gotten in taxis in New York, when I lived there, and said, “I’ve got a huge tip for you if you can get me to FedEx by 9:15.” And then tear down the streets. I remember that with a Washington Post job. Yeah, I’ve had some hairy, you know, I’ve gone to...

Patrick Mitchell: ... So you haven’t had to drive from Connecticut to Manhattan to deliver something at midnight?

Barry Blitt: None of that. In Montréal, I once had to get to the FedEx desk at the airport. Maybe that was the most dramatic. There were helicopters above, like, firing at me ...

Untitled Hitler sketch, c. 2015

Patrick Mitchell: But now, because of the digital age, you’ve had to become an expert scanner, right? Because you do your own digitization.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. The digital age has changed all illustrators’ lives. And writers too. But they used to drive reference [materials] to my house. They’d have photos of Cher, and the driver would wait outside and I’d draw Cher or Sting, or whoever I was drawing at that time, and then give it to the driver.

And now it’s crazy easy to scan something. I still don’t know how to use Photoshop. My life would be so much more complete if I could figure out how to move things around on my drawing in Photoshop. People have tried to show me the lasso tool but I don’t just don’t know what to do.

Patrick Mitchell: Our friend would recommend that as an opportunity for a gummy.

Barry Blitt: I don’t understand that sentence.

“Our friend would recommend that as an opportunity for a gummy.”

“Our friend would recommend that as an opportunity for a gummy.”

Patrick Mitchell: Our friend uses gummies when it’s time to do intensive Photoshop work.

Barry Blitt: Oh really?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. And I thought that was genius. And I thought, well, you know, there are times when you just need to—I just don’t associate weed with productivity. But apparently I’m wrong about that.

Barry Blitt: It’s good for creativity. I mean, I wouldn’t—I try not to drive.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. No, we’re not going back. We’re going to keep going: Air Travel. I read that you once went 18 years without flying.

Barry Blitt: I did go a long time without flying. I finally went to visit my son who lives in London now, and I went, I guess when he graduated college over there. So that was, I don’t know how many years ago.

I’ve been flying since. I’ve been flying for the last eight years or so. Although I finally flew, Covid-wise, I flew to visit him again a few months ago.

Patrick Mitchell: So is it fear of flying or just airport hassle or…?

Barry Blitt: No, it’s fear of flying at the hub of it. Then there’s airport hassle in a ring around it. And then there’s the further control issues, getting to the airport, traffic. I hate traffic. That’s another thing that drives me crazy, by the way. Yeah, it’s a control issue, I think. But I’m working with Dr. Mennesson on it, and I’m making some big strides.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you have a flight on the calendar coming up?

Barry Blitt: I do not, thankfully. I wouldn’t be this voluble and easygoing if I had a flight to be nervous about.

A recent piece for Air Mail

Patrick Mitchell: All right, I’m almost through with you. I’m going to read two quotes about you.

Barry Blitt: Okay.

Patrick Mitchell: And two quotes from you, and then follow up with the question, and then I’d like a follow up to that.

Barry Blitt: Okay.

Patrick Mitchell: In two parts.

Barry Blitt: Okay. Go ahead.

Patrick Mitchell: This is David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker: “For nearly a generation now, Barry Blitt has been the sharpest and funniest political artist in the United States.”

Barry Blitt: Okay. Stop it.

Patrick Mitchell: And here’s Steven Heller: “There can be no disputing that Blitt has earned a vaulted place in the pantheon of 21st century political satirists.”

And now two quotes from you. “I’ve tried not to get too obsessed about it, the Pulitzer. And now I’m back to working and beating myself up every day. Resting on this kind of laurel is probably dangerous for me.”

And this one: “At this point, I’m just living out my remaining time.”

So my question is—and I already know your answer to this, but let’s workshop a new one.

Barry Blitt: Let’s workshop it.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you ever let yourself take in and savor your accomplishments? I mean, I could totally see a Mark Twain Award or a Kennedy Center Honors for Barry Blitt.

Barry Blitt: You’re bullshitting me, but ...

Patrick Mitchell: ... that would be totally within the realm of possibility.

Barry Blitt: Well, yeah. Adam Sandler got one, so I guess anyone can get one.

“I just don’t like someone talking at me. It seems like Fox started it. I don’t know if they did, but it’s just no fun. I don’t even like to hear the things that I believe shouted back at me stridently by some clown on TV.”

Patrick Mitchell: And so, I mean, at some point us old guys have got to be able to celebrate our success. Or what’s it all for?

Barry Blitt: You know, I go through my flat files of drawings looking for something and sometimes I’ll see drawings that make me laugh, that I’m pleased with. I mean, I don’t know if that answers your question.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I mean, I, I say this as someone close to your age, at some point you’ve got to be able…. I’m close to your age…

Barry Blitt: Oh, I thought you said “cage.”

Patrick Mitchell: I’m close to your cage too. But, at some point you just have to let yourself— you have to celebrate your success. You have to own what you’ve accomplished. And you’re a legend in our business. There’s just no two ways about it.

Barry Blitt: Oh, Jesus. I think you’re mixing me up with somebody. I’m happy to be working. And I’m happy to have great gigs, you know? It’s thrilling to do a New Yorker cover or to do anything for The New Yorker. Or to do stuff for Graydon Carter. And yeah, I don’t have big complaints. The last few years have been great as far as work goes. And it’s nice to get good input, but I get bad input too, you know.

Patrick Mitchell: But even bad input is good input because input means people are paying attention.

Barry Blitt: I don’t know about that. I mean, if someone’s punching you in the face, they’re paying attention.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s negative reinforcement.

Barry Blitt: I guess.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. Last question: you wake up tomorrow, all your bills are paid, there’s no deadlines. What would you do?

Barry Blitt: I would do, probably, what I always do, which is try to make myself laugh. You know, sit at the drafting table and make myself laugh. Sit at the piano, make myself laugh. I think there’s—a good portion of it is trying to generate some laughter, you know, out of thin air for myself. Yeah, I mean, I’m always drawing and I expect that’s what I’ll be doing until they, you know, load me into my flat files.

Patrick Mitchell: Actually, I could see you have a Godfather ending. You know, you’re out there in the tomato vines...

Barry Blitt: Right.

Patrick Mitchell: ... putting an orange in your mouth and you keel over.

Barry Blitt: I can definitely see the keeling over. The keeling over. I mean, I think about that all the time.

Patrick Mitchell: Would you be wearing short pants?

Barry Blitt: There’s much more to me than the short pants. But I appreciate you dwelling on them. I honestly do.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I tried to make you the greatest illustrator of our time, but you weren’t having it. So I went back to the old short pants.

Barry Blitt: Yeah. Well, it’s hard to argue against short pants.