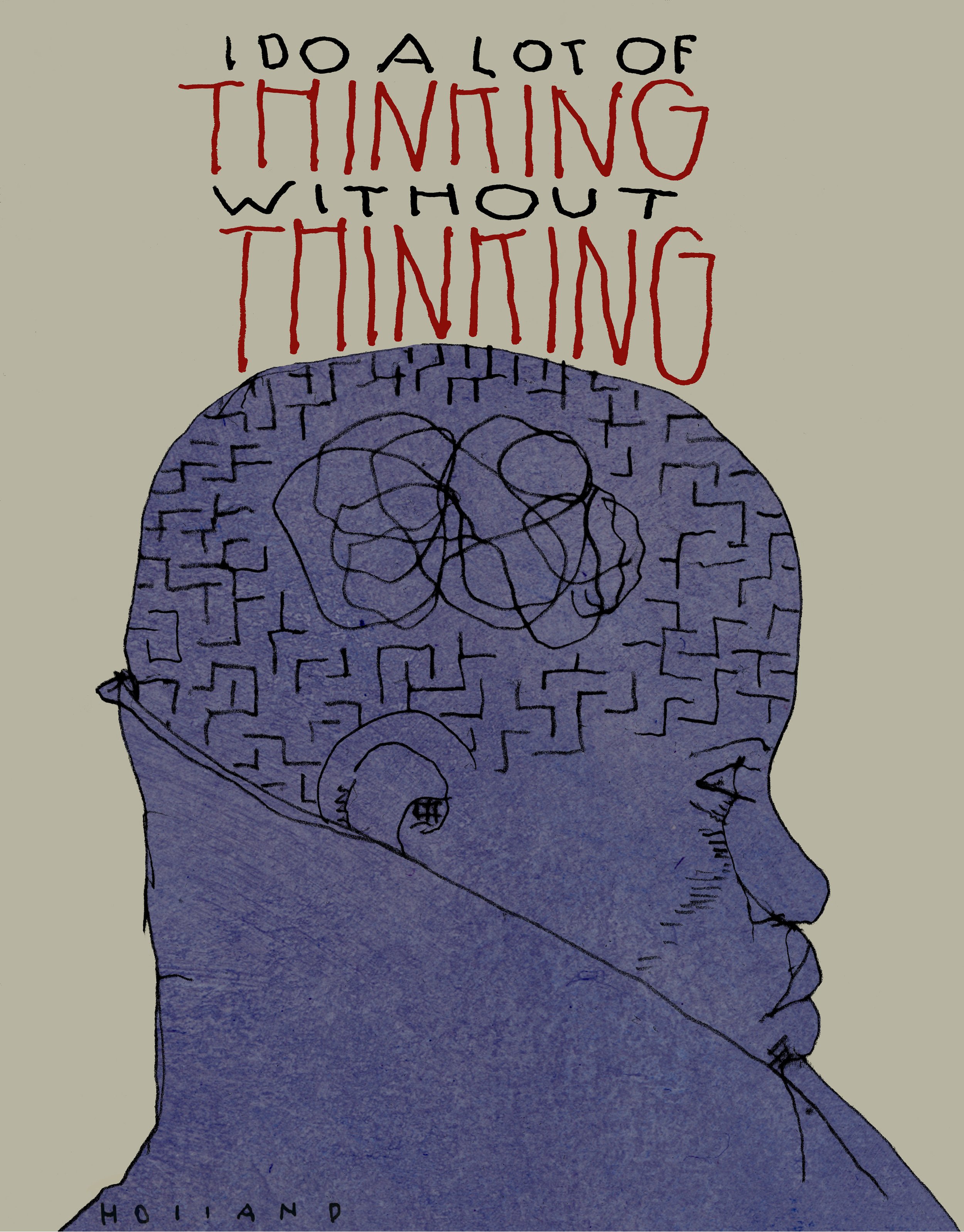

Something More Personal

A conversation with illustrator Brad Holland (Playboy, Time, The New York Times, more)

It’s 1967 and your train from Sandusky, Ohio, just rolled into Grand Central. You’ve got a suitcase in one hand and your portfolio in the other. You exit the station and take a right, uptown, before realizing it’s the wrong way. (It’s ok, you’re not from around here). So you turn around, and head down to 223 East 31st Street, the studio of the celebrated designer Herb Lubalin, who was about to give you your first assignment in the big city.

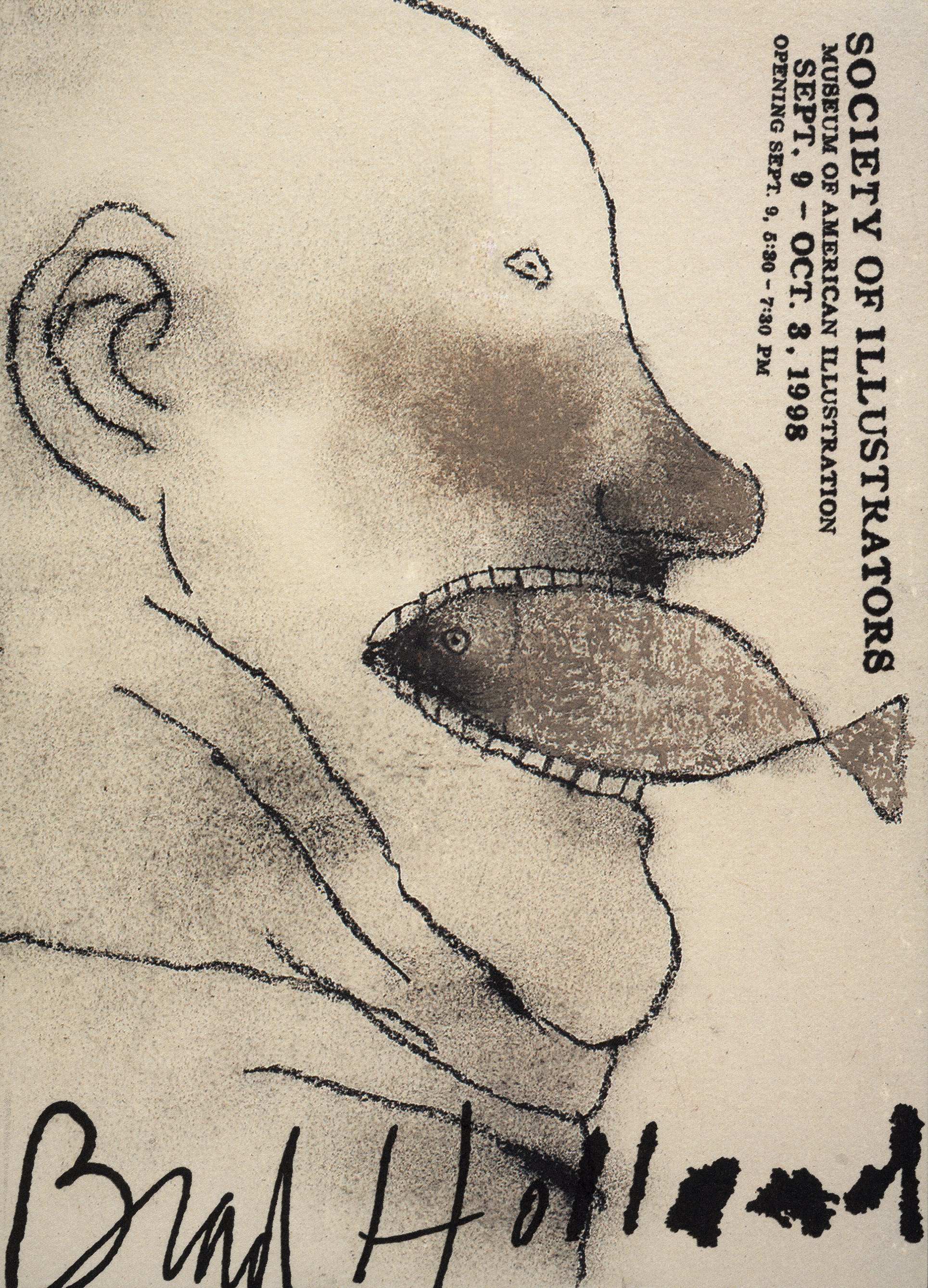

And so begins the career of legendary illustrator Brad Holland — a 50-plus-year career that put him on the Mt. Rushmore of contemporary American illustration alongside Milton Glaser, Edward Sorel, Ralph Steadman, Seymour Chwast, and the recently-departed Marshall Arisman.

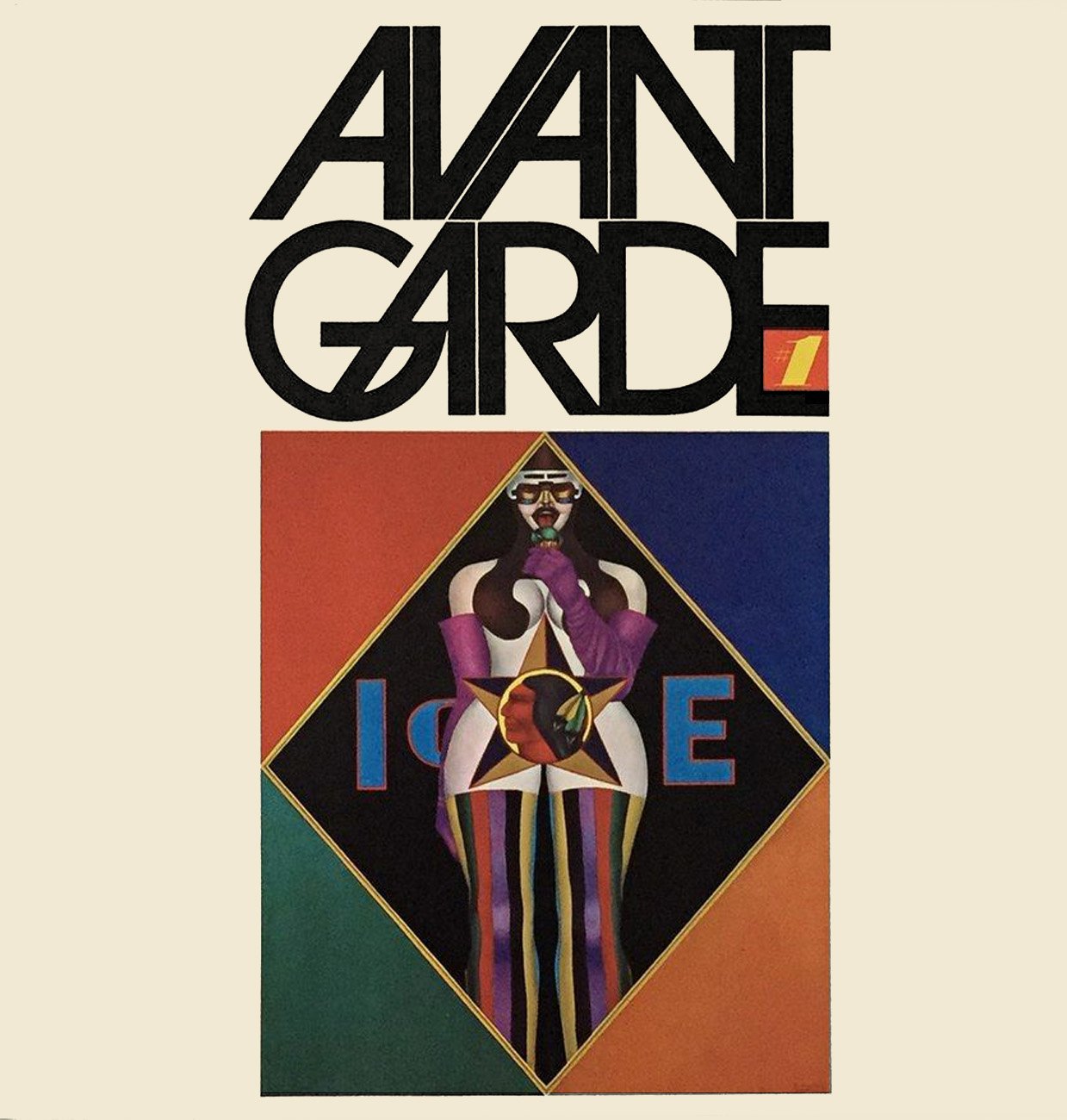

When you begin your career in the Summer of Love, at some point the conversation is gonna turn to sex. After turning in his first piece to Lubalin’s Avant Garde, a magazine with mild sexual themes, Holland’s next few assignments came from magazines who liked it a little rougher: Screw magazine and The New York Review of Sex, before finally landing a steady gig at Hugh Hefner’s Playboy.

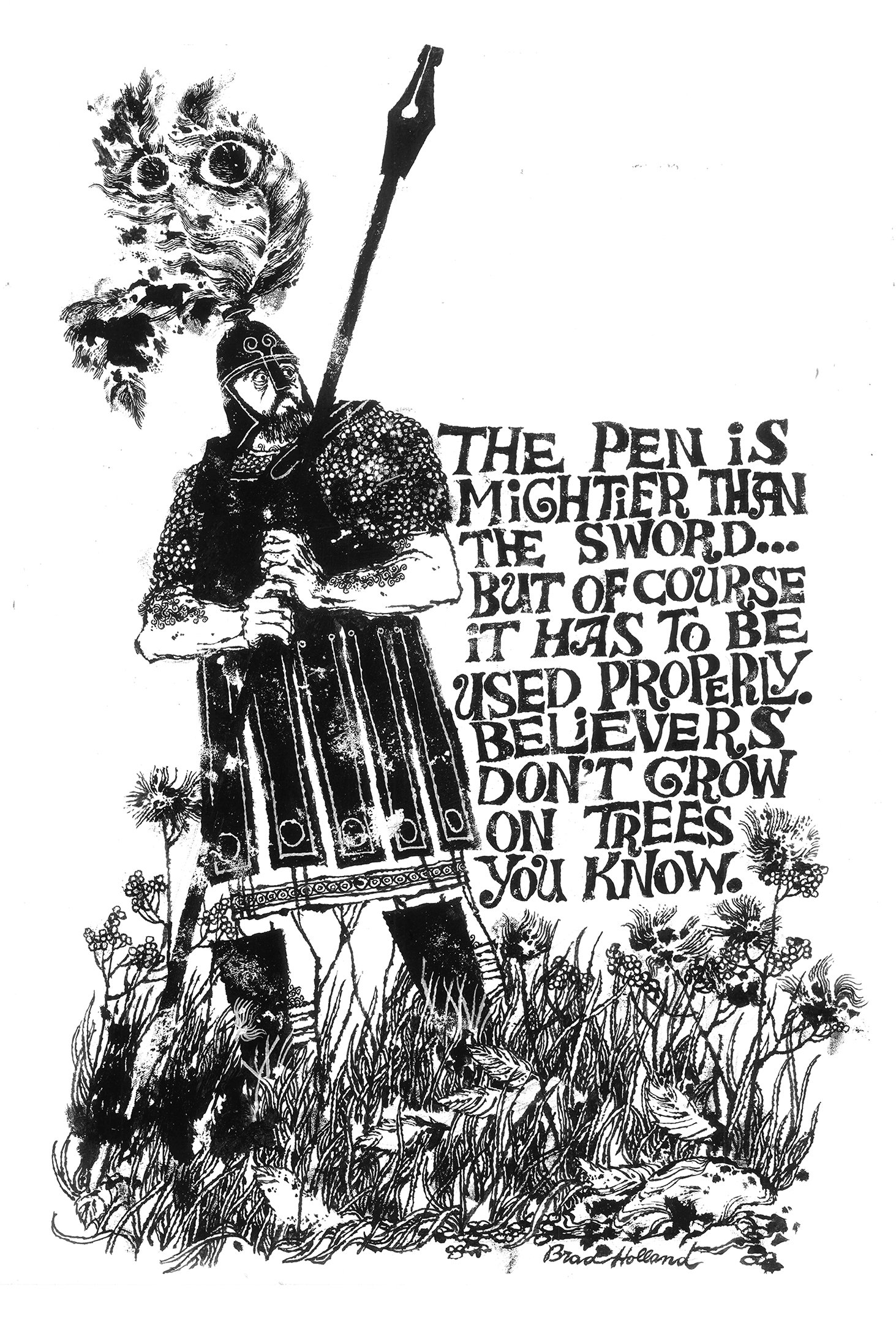

As Playboy’s legendary art director Art Paul would soon find out, Holland wasn’t like other illustrators. Inspired by Gary Cooper’s Howard Roark in the movie The Fountainhead, who battled against conventional standards and refused to compromise with the establishment, Holland was not willing to execute the spoon-fed instructions given by magazine art directors. He revolutionized the illustrator-for-hire dynamic. It changed everything.

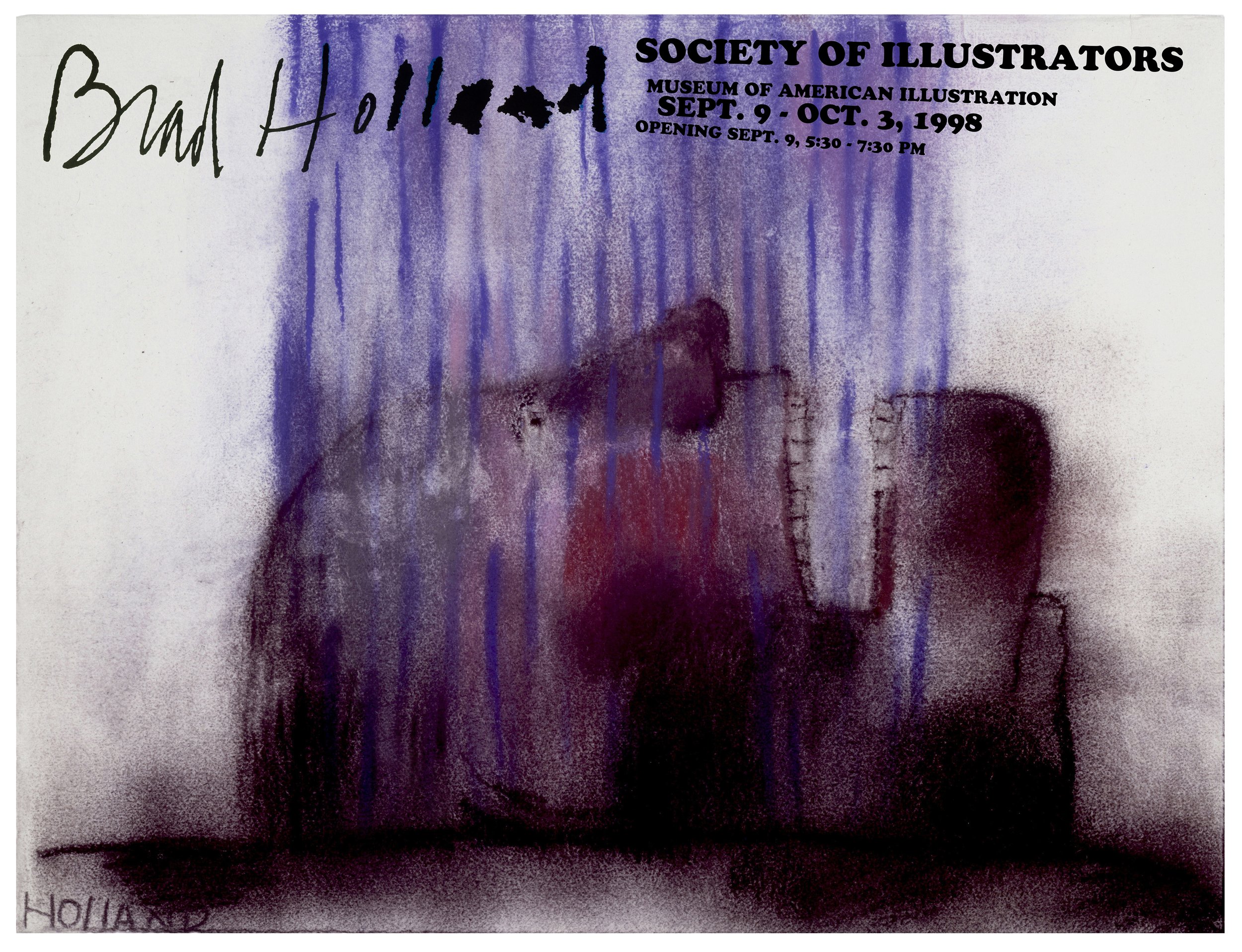

In this episode, Holland talks with our editor-at-large and esteemed design critic, Steven Heller, the co-chair of the MFA Design Department at the School of Visual Arts in New York, an Art Directors Club Hall of Famer and AIGA Medalist, who also calls Holland one of his oldest friends and mentors.

They talk about their early days together, what it’s like to tell your mother that you’ve finally sold a cover illustration—to Screw Magazine, how to say NO to a creative director, how to crop an Ayatollah, and—spoiler alert—how to avoid getting mugged in Alphabet City.

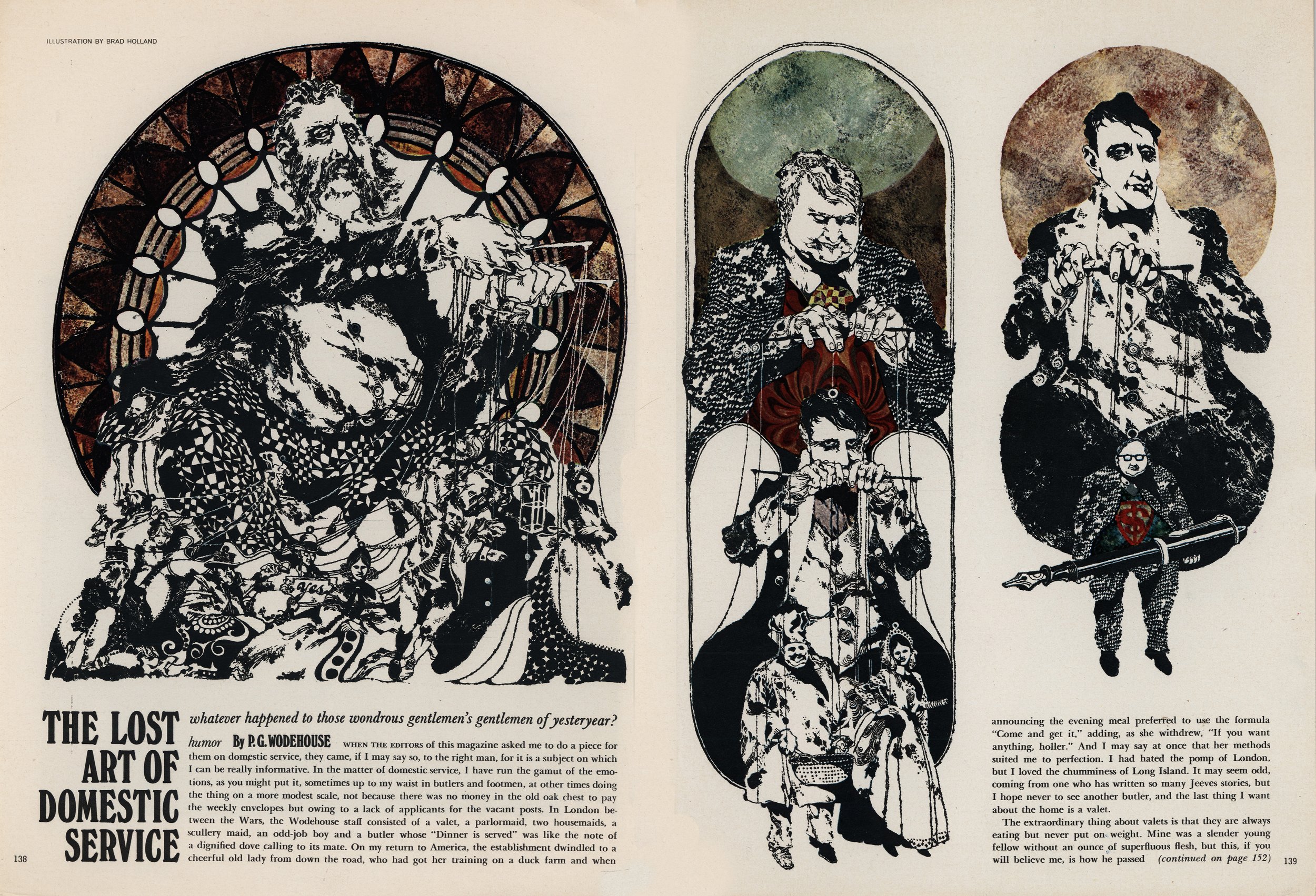

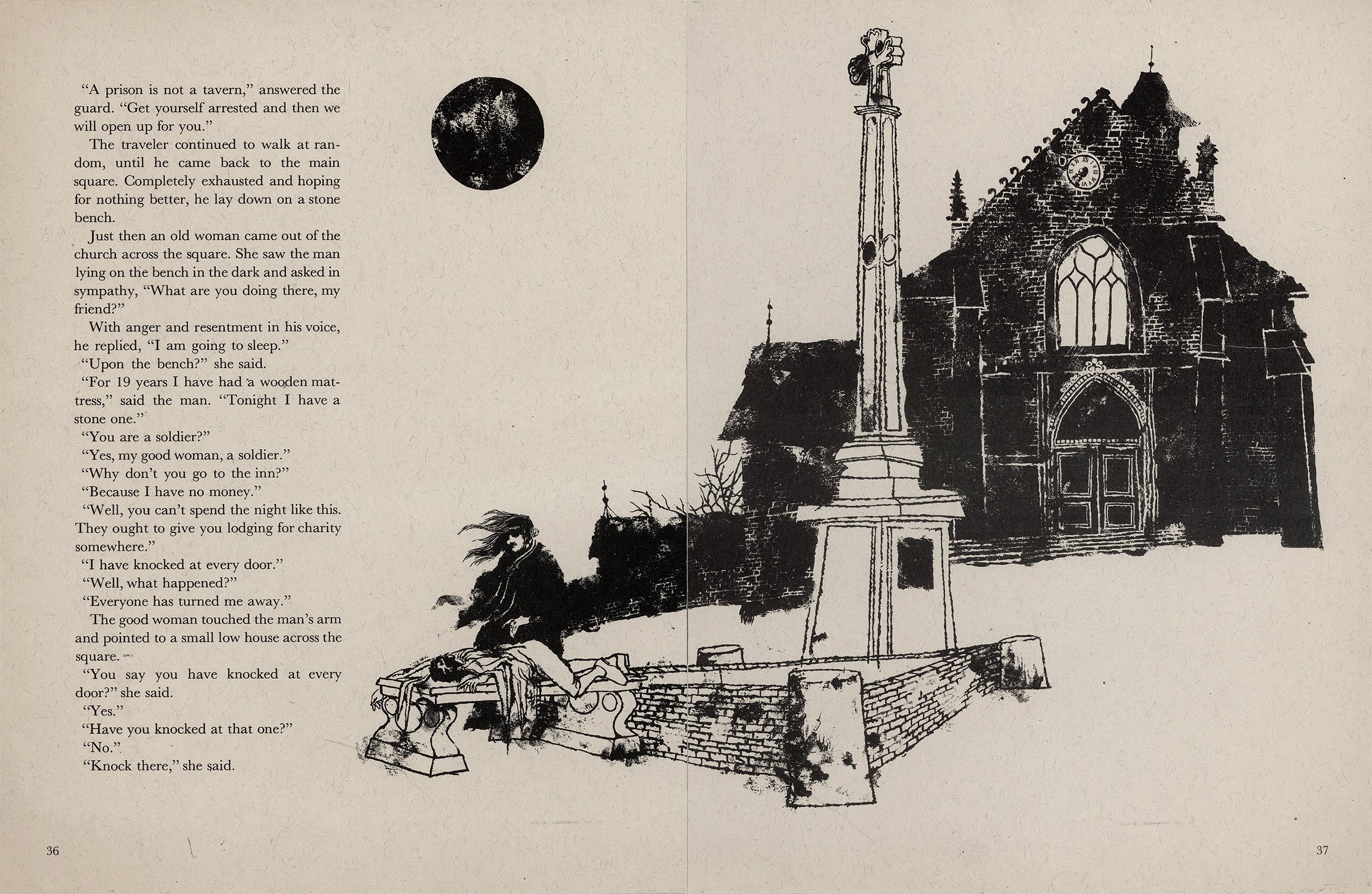

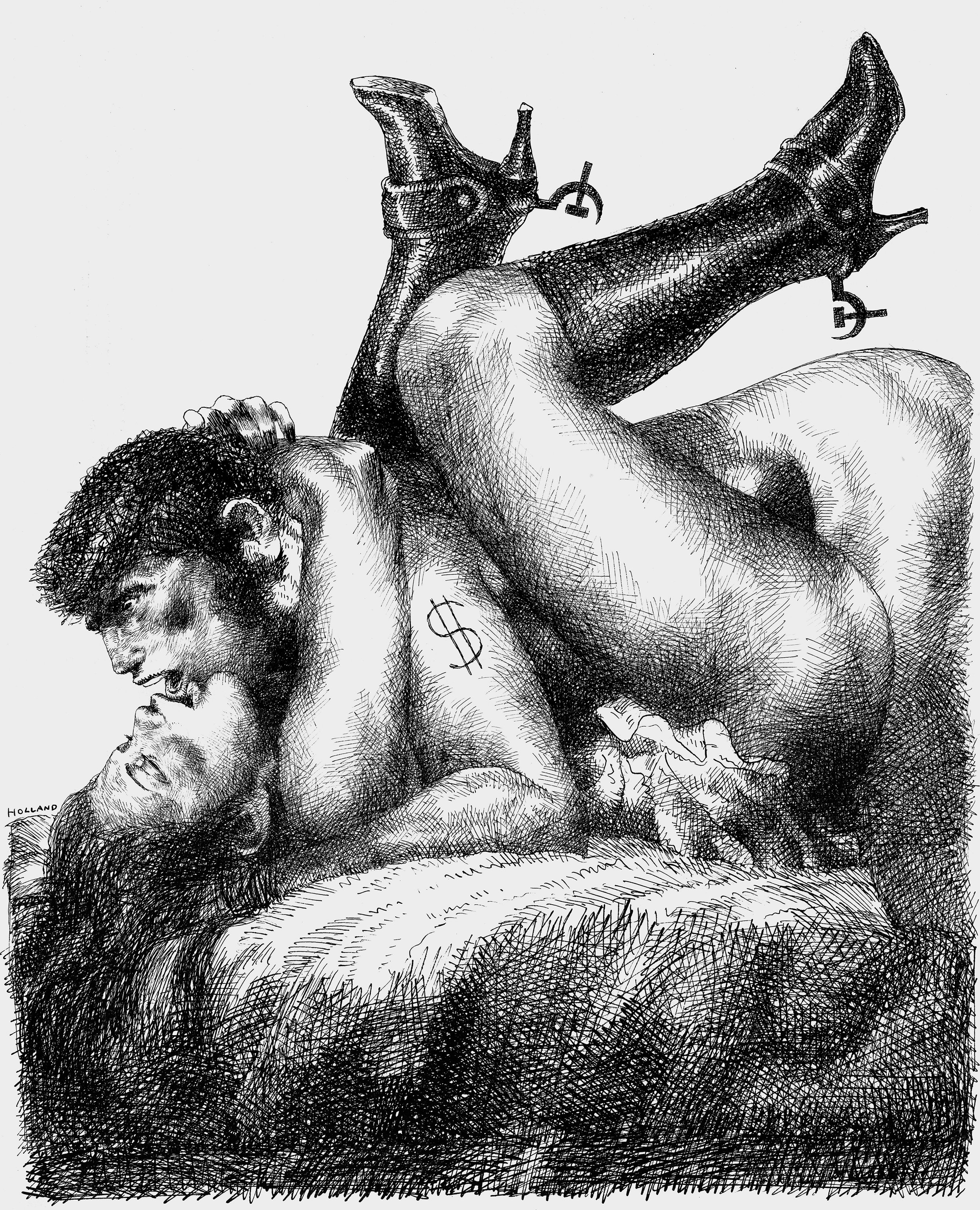

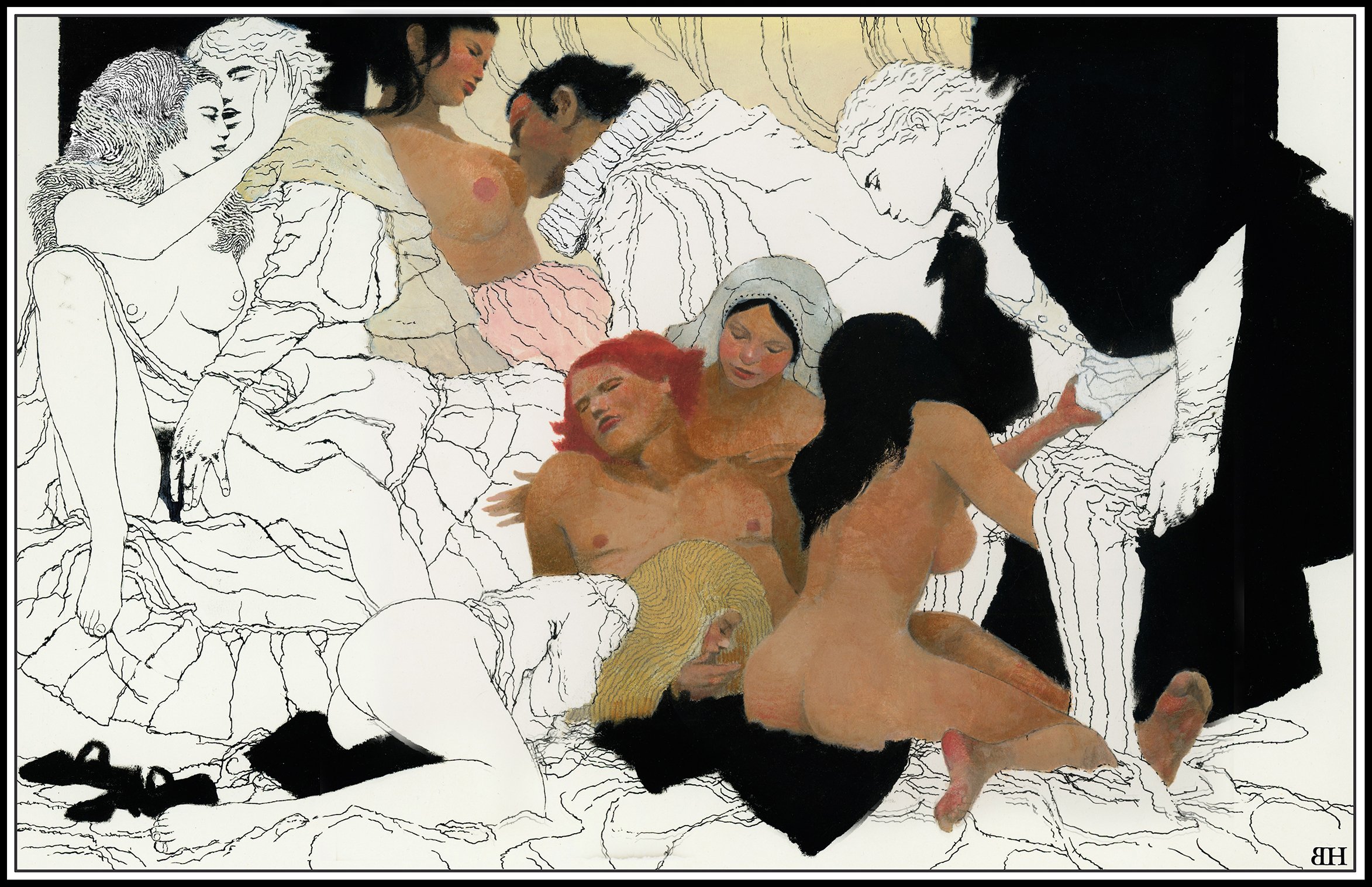

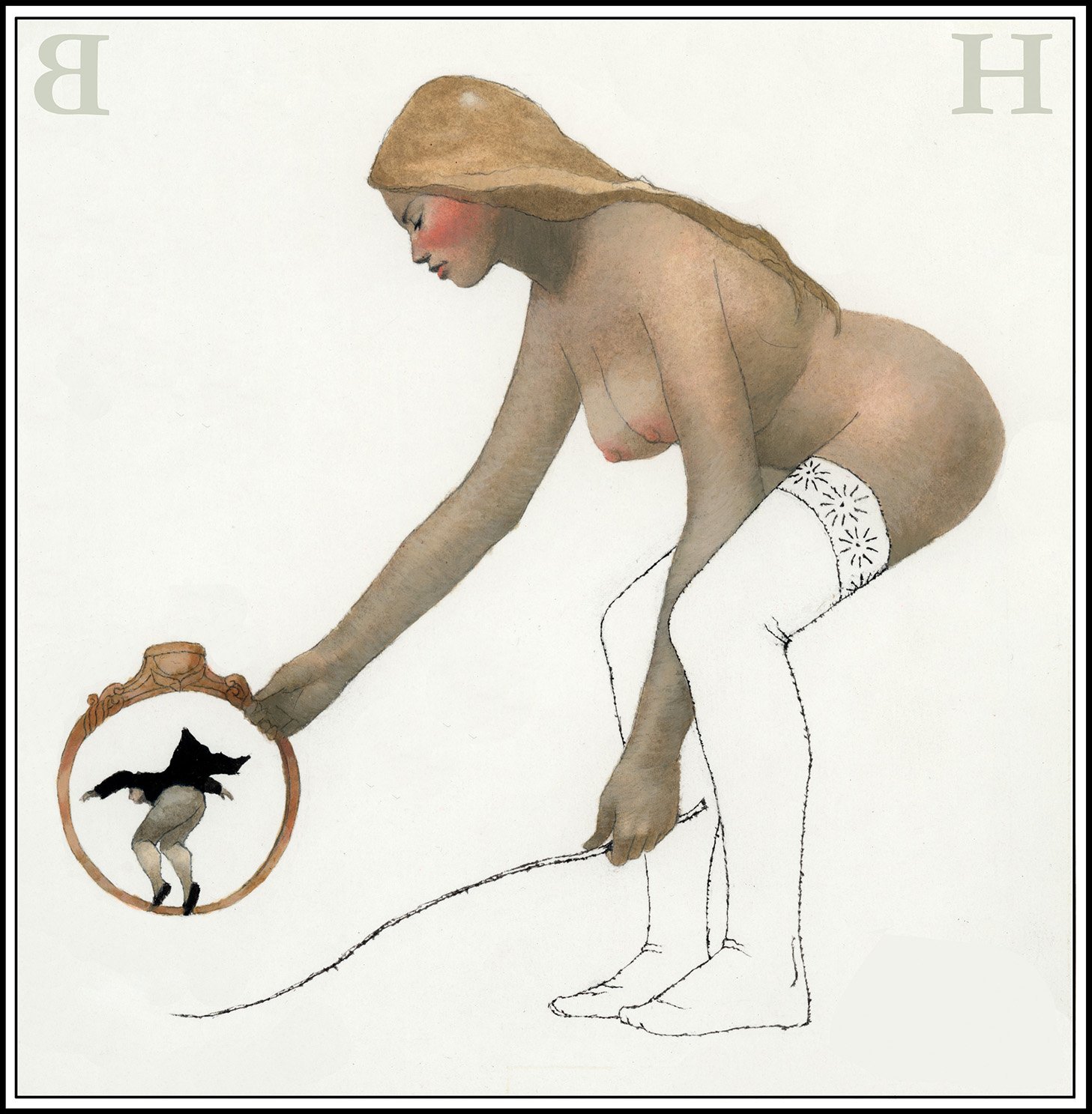

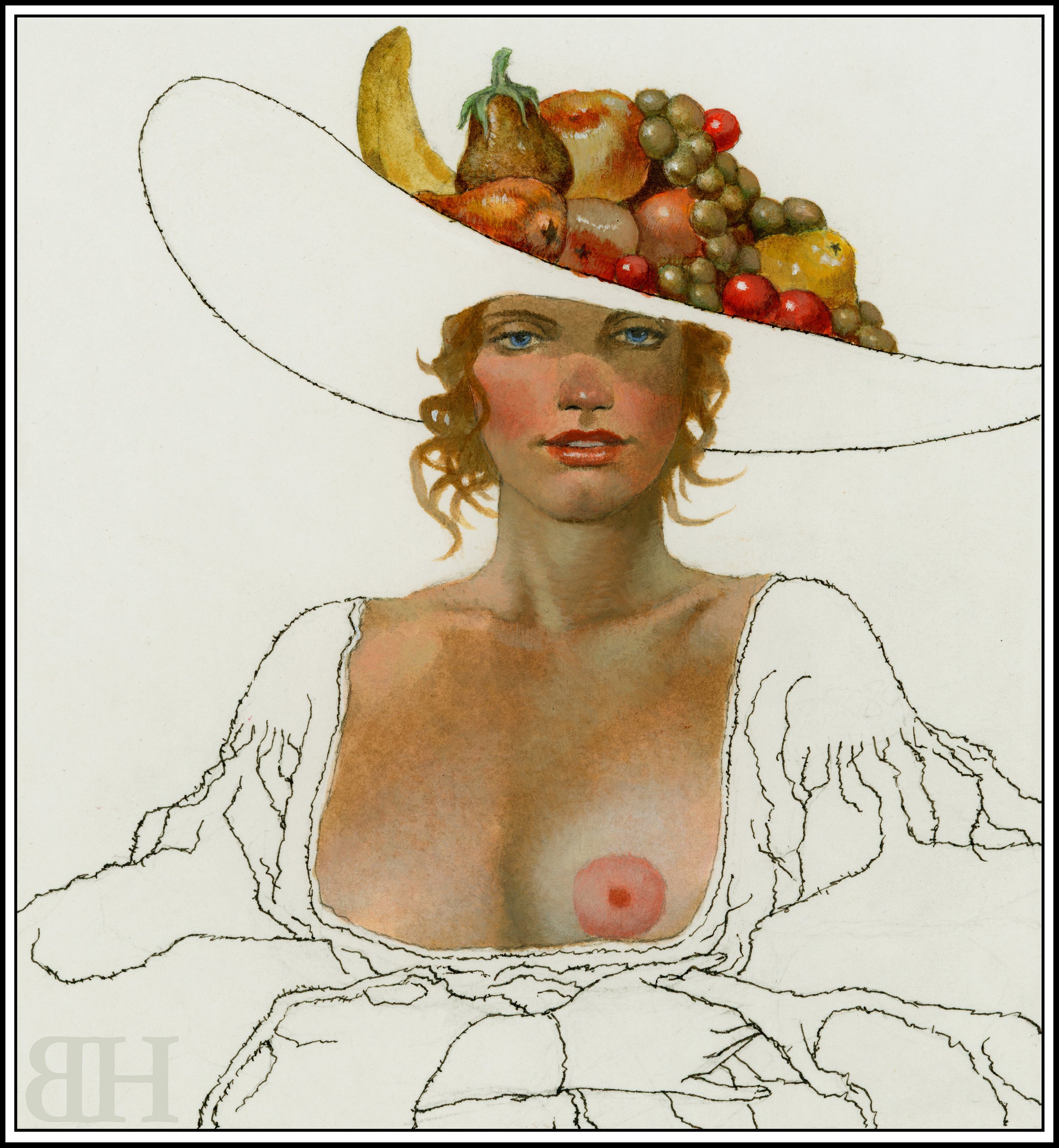

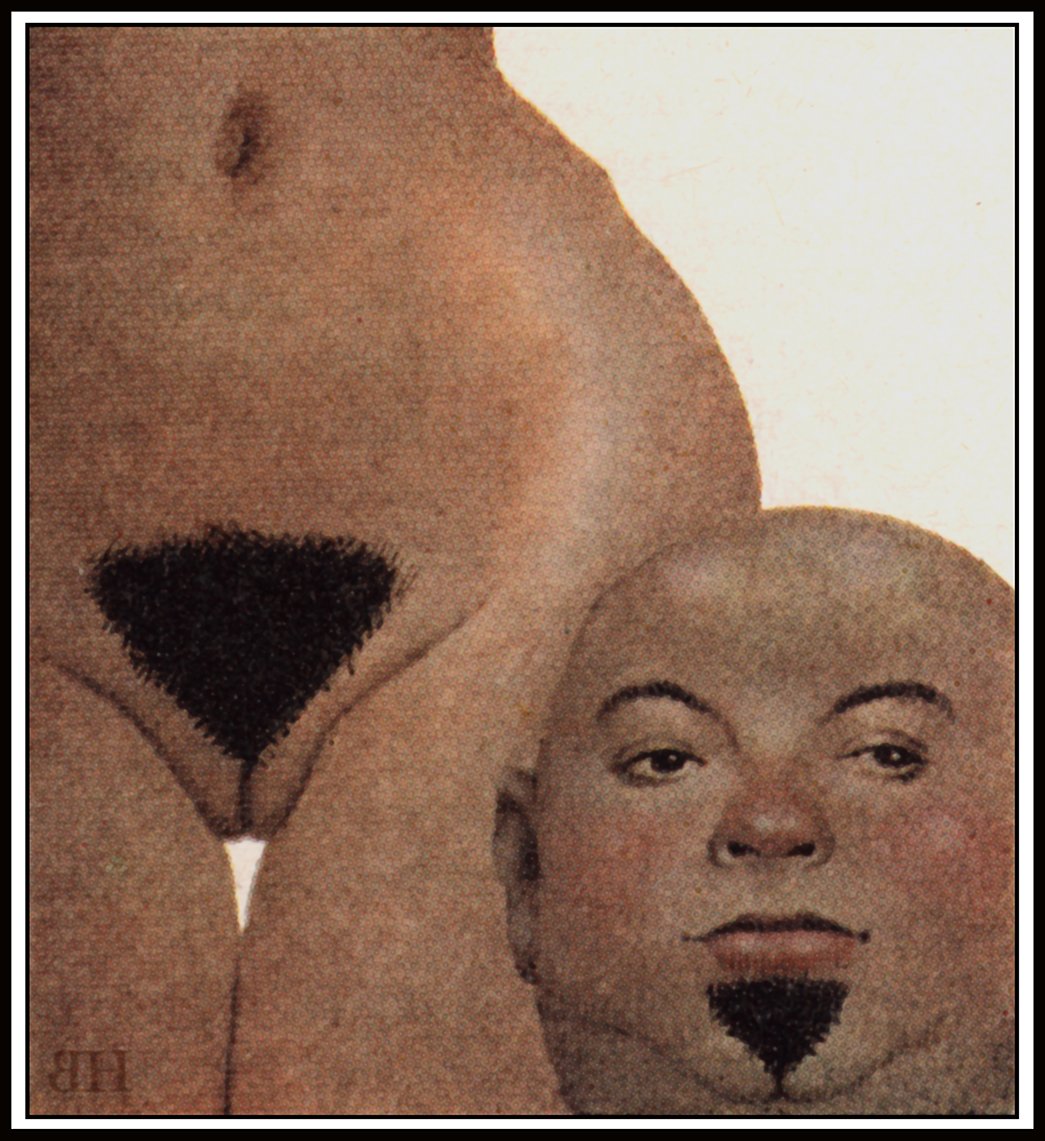

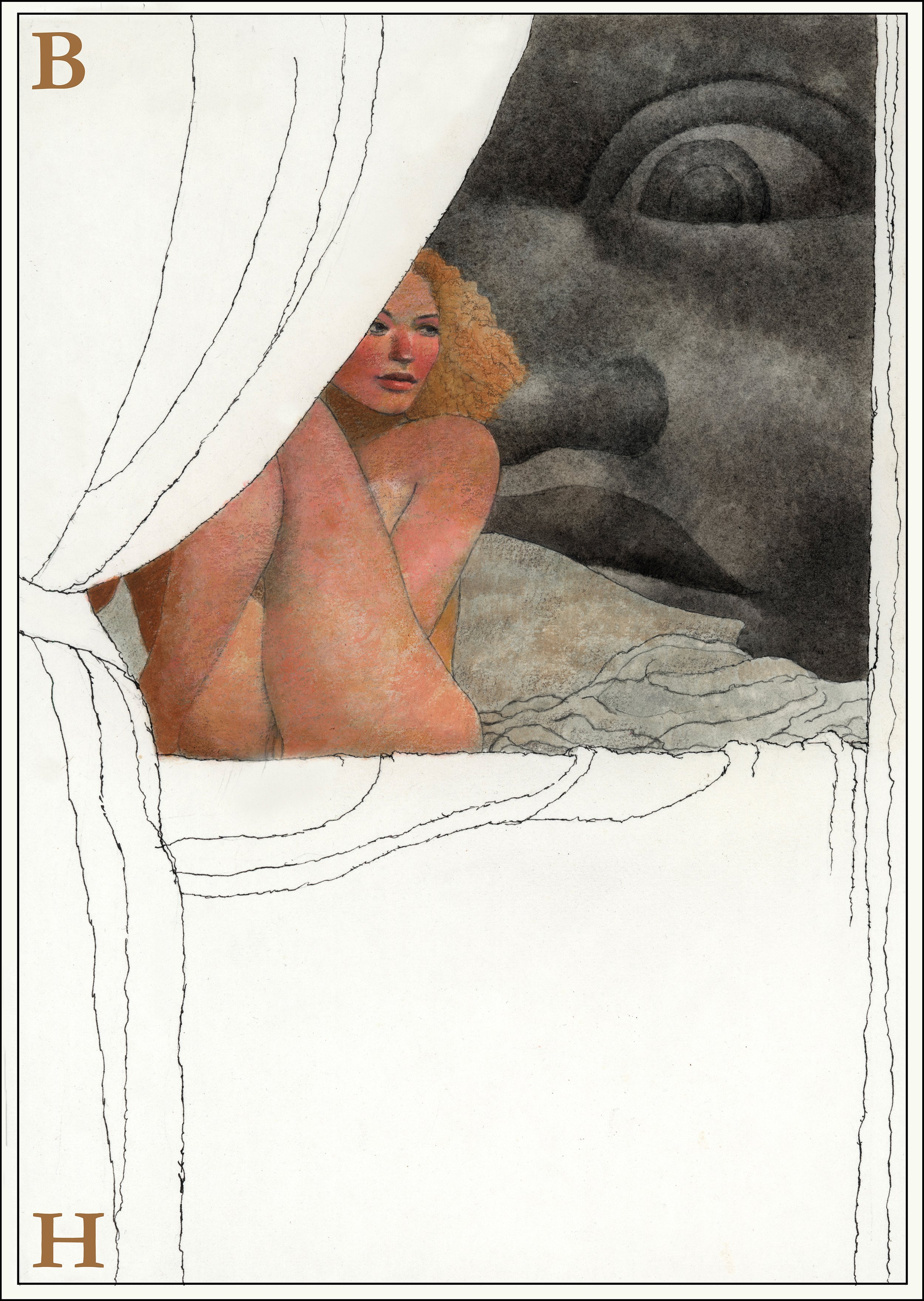

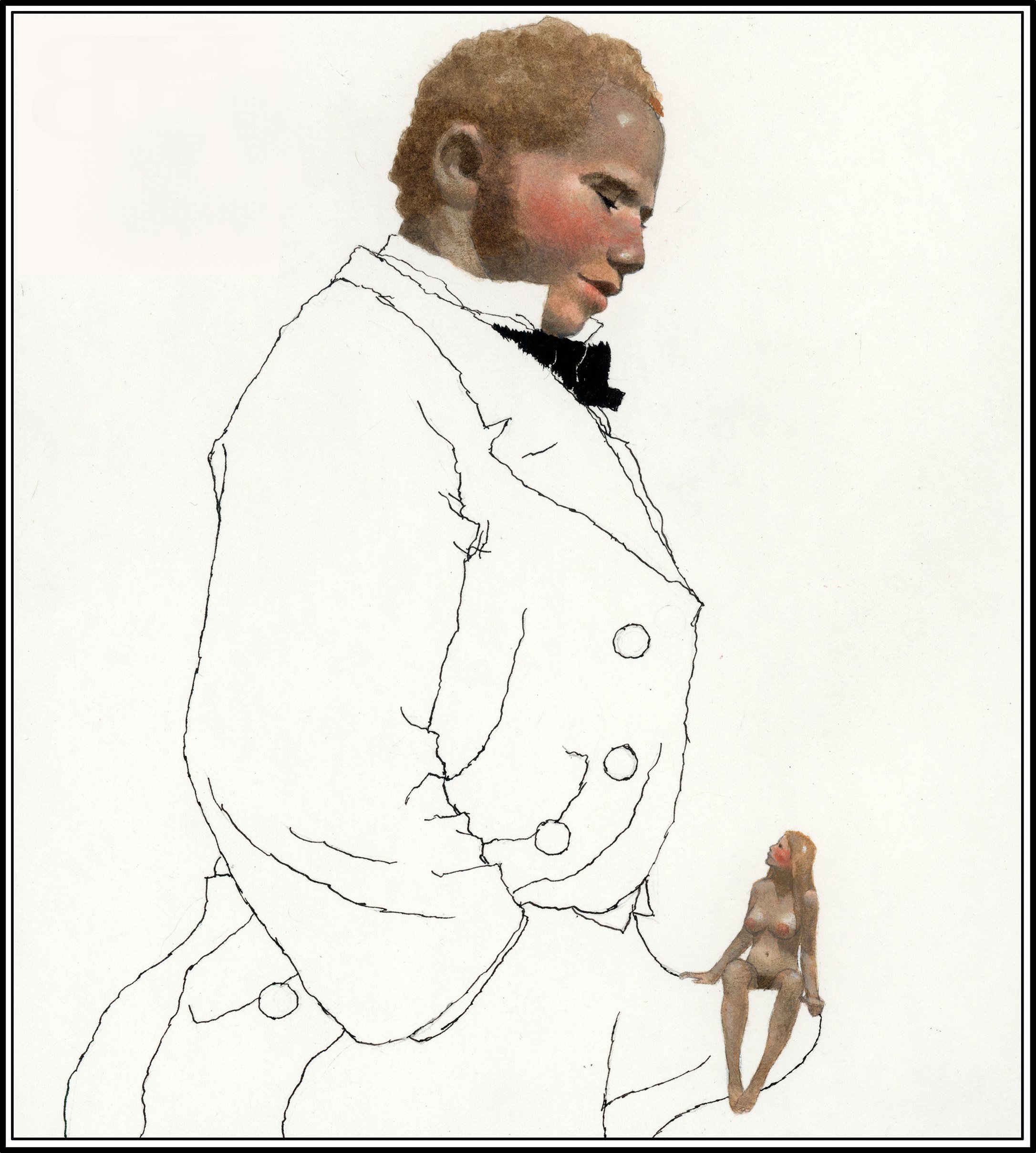

Holland hit the big time when he began illustrating a recurring feature for Playboy called Ribald Classics.

Steven Heller: I want to start by saying that Brad is the oldest friend I have on the planet (that I know of), and Brad came into my life at just the right point. He became my teacher, my mentor, my role model. And we haven’t really talked an awful lot in the last 20 or 30 years, so this is a great opportunity to talk about what we’ve been through in that amount of time and particularly how his work not only affected me but affected the magazine business in general, of which I’ve been a part.

So the first question I have is more of a “conversation piece.” I remember when you got off the bus from Fremont, Ohio. It was one of those places…

Brad Holland: … Beyond the Hudson.

Steven Heller: … Beyond the Hudson. And we met when you came and answered an ad for a magazine that I was doing and didn’t know squat about magazine design, but you had already plunked yourself down in New York City. And your first illustrations were in Avant Garde with Herb Lubalin as art director.

And just to start off, I’d like you to recall what that period was like for you.

Brad Holland: The first thing is, it was the so-called “Summer of Love.” Remember? Everybody was supposed to be going to San Francisco with “flowers in their hair.” I, apparently, caught the wrong bus because I came east and I had no flowers whatsoever in my hair. And I did come, I’d come a long way…. I had left my job in Kansas City. I’d been working at Hallmark.

Well, thank you for the kind words, first of all. I didn’t mean to be impolite. I didn’t want to cut you off at the time.

Anyway, I had been working in Kansas City for two years. I had left Ohio when I was 17, when I graduated from high school and went to Chicago.

I’d never been to a big city before, so I didn’t exactly know what I was going to do when I got there, but I figured I’d find out once I got off the bus in Chicago. I worked there for 18 months and then I got a job at Hallmark where I became a supervisor and did a lot of book illustrations, which gave me a good portfolio.

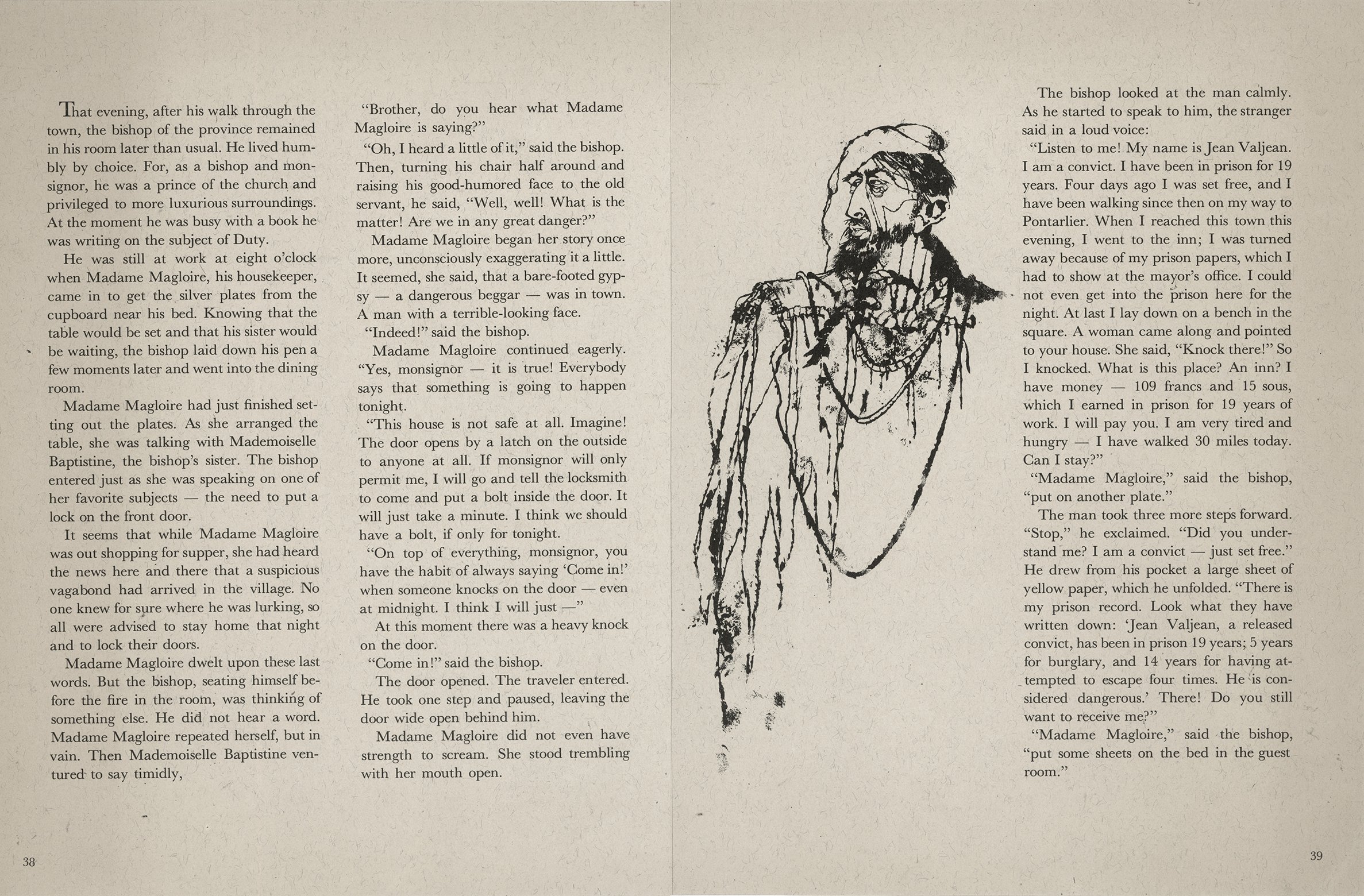

And I just quit my job and came to New York with absolutely no idea of where I was even going to stay the first night. I didn’t know anybody. I stopped off in Ohio. My grandfather just had his leg amputated. And so I spent a month there driving him up to Toledo so he could learn how to walk with his artificial leg. Then I caught the bus to New York.

Steven Heller: But did you have a sense of what the good magazines were?

Brad Holland: Oh no. The best thing you could do about magazines was just go to the newsstand and look at them and see which ones look like they might use me. The thing that made a difference in my case was Herb Lubalin was art directing a funny magazine called Fact in those days. And Fact was one of Ralph Ginzburg’s fairly eccentric publications. He had published Eros back when I was working in Chicago, and I don’t remember how many issues it had—it was a quarterly, and it has a hardcover, kind of based on Horizon magazine. And he had some good people, except that he decided to be clever. Since it was a magazine designed around erotic art, he decided to mail it from Blue Balls, Pennsylvania, and Intercourse, Pennsylvania. And he sent the subscriptions out from those two cities and the government got him for pandering.

“I had been working in Kansas City for two years, and I just quit my job and came to New York with absolutely no idea of where I was even going to stay the first night. I didn’t know anybody. I stopped off in Ohio. My grandfather just had his leg amputated. And so I spent a month there driving him up to Toledo so he could learn how to walk with his artificial leg. Then I caught the bus to New York.”

Steven Heller: Yes. Pandering was the charge.

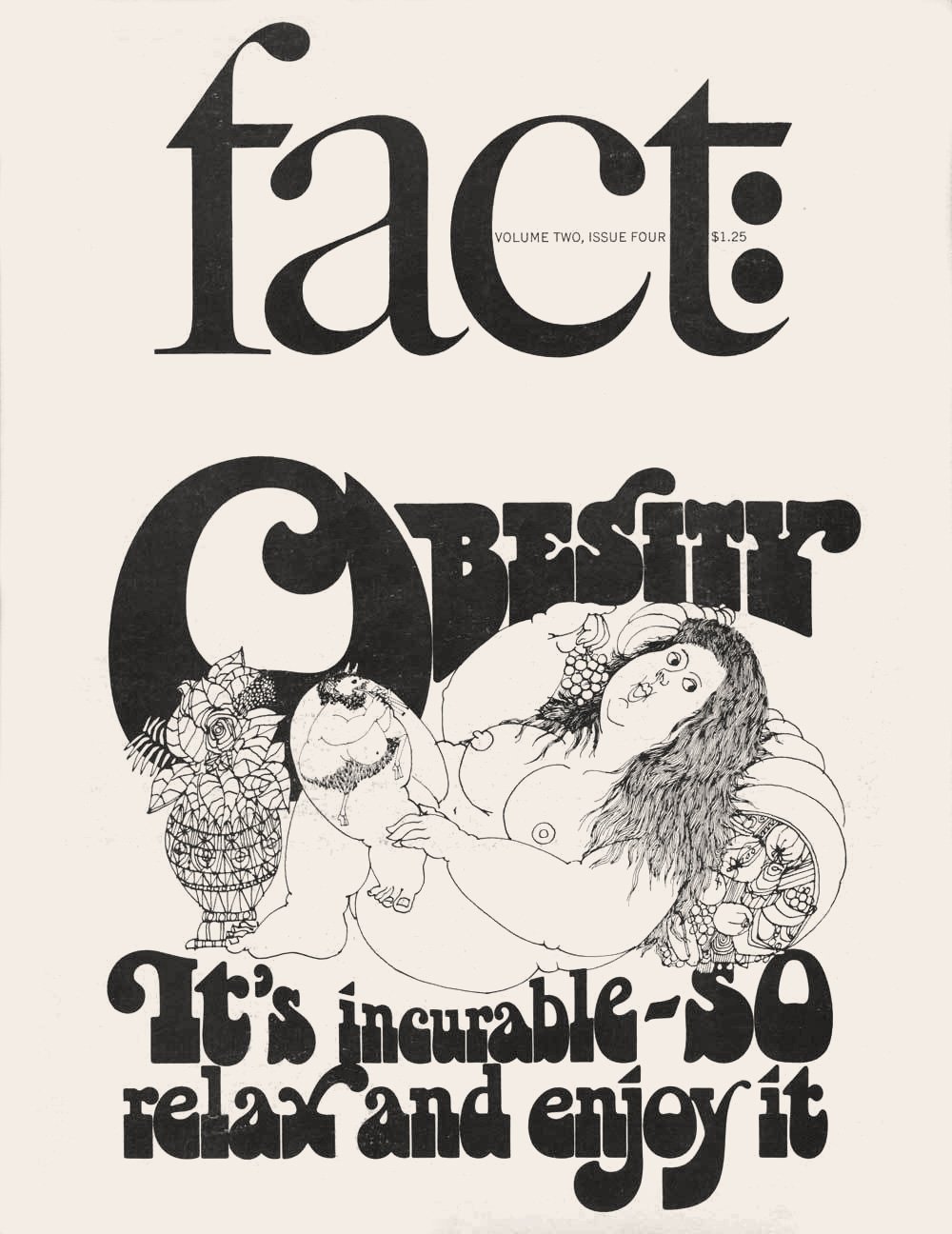

Brad Holland: He had used the US mail to pander. And that closed down the magazine. His second one was Fact, which was kind of a combination of Consumer Reports and The National Enquirer. It was full of articles about how Coke was going to give you cancer and so on. But the one thing about it was Lubalin was such an adventurous art director that he would design every issue using one artist to do black and white artwork for all the articles.

And I started following this because my friend Jim Parkinson had told me about it at Hallmark. Parkinson is a great lettering artist. And Lubalin of course used typography beautifully. So Jim was the one who told me about Fact, and I began following it.

Lubalin used type beautifully in Fact, but he also got artists to do single issues, and they would do everything. And a lot of artists would just paint pictures and then they’d be running in black and white. But there was one issue just before I came to New York, it was done by Etienne Delessert and used his ink drawings beautifully. And so I had, in my mind, when I got to New York, I was going to see Herb Lubalin, and I didn’t waste any time. I got off the bus. I mean, I got off the train rather. I took a bus to Sandusky, and then caught a train from Sandusky to New York. Anyway, I got off the train and put my suitcase—I had a suitcase and a portfolio—put my suitcase in a locker. They still had lockers in Grand Central Station in those days. And I went to a telephone booth and called Lubalin’s office.

They wouldn’t look at my portfolio, but they said I could drop it off. So I dropped it off. I went out on the street. I didn’t know New York at all. Didn’t know anybody. I found myself on 42nd Street and I started walking one block, and I was on 43rd Street. So I knew I was walking in the wrong direction. I was headed for, I think it was 31st. So I just went in the other direction, walked on down until I found the place, dropped off my portfolio, and went down to Greenwich Village. I had located it because I’d seen a cartoon with a hippie standing on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Eighth Street, so I knew roughly where Greenwich Village was. And I got something to eat. I went back to the studio, went back to Lubalin’s office, and he had a job for me, except I had to do it in two days.

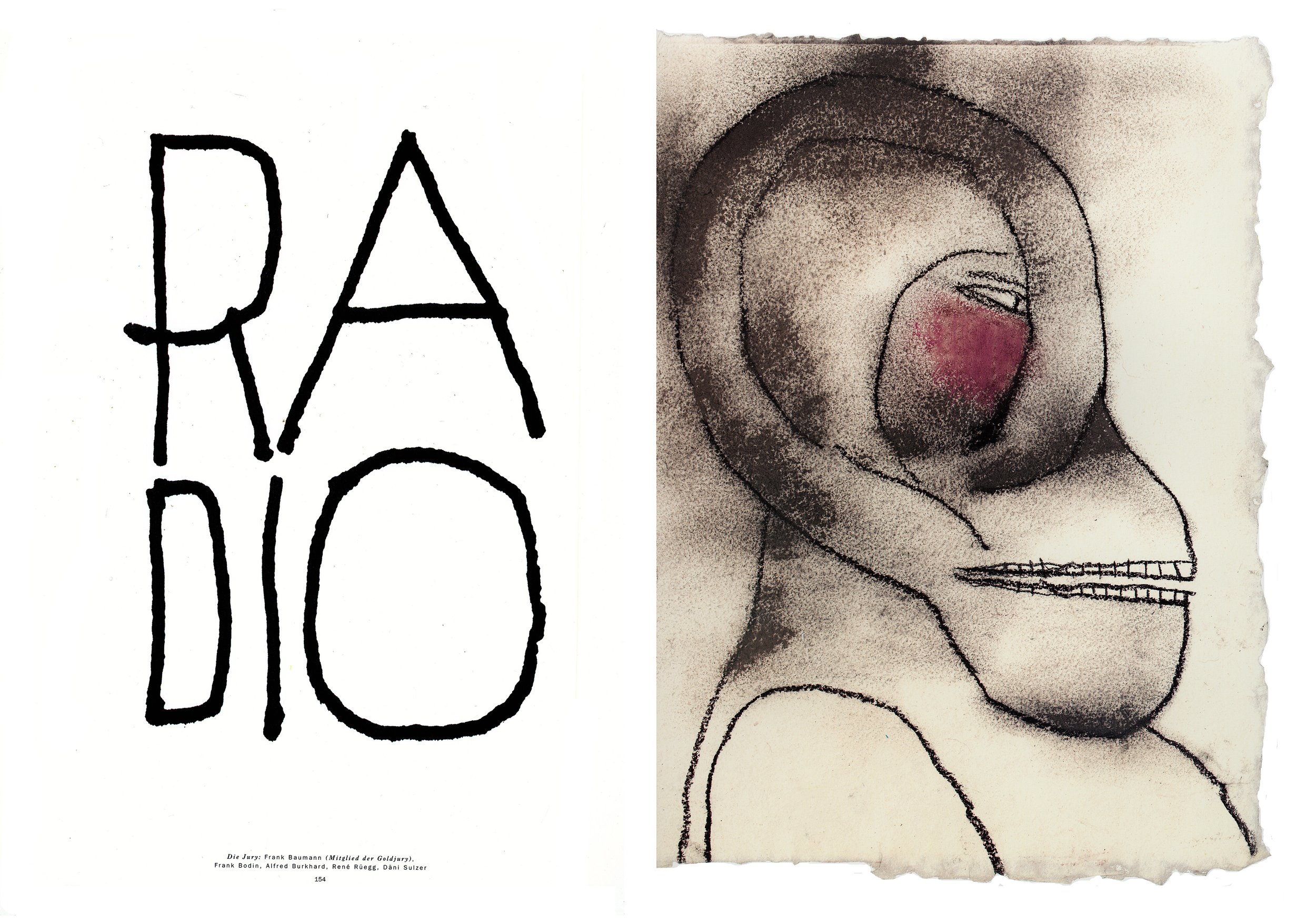

Magazines designed and art directed by Herb Lubalin, who was an early fan of Holland’s work.

Steven Heller: And you had no place to live.

Brad Holland: Well I asked him, and yet I didn’t have any art supplies either. So I asked him where I could find an art store and he said, what, neighborhood do you live in? And I said, I got a locker at Grand Central Station.

And he said, “How long have you been in New York?” And I said, “What time is it?” I’d been in New York for four hours at that point. I found a hotel in Times Square, and I went to the Walgreens that was on the corner of Seventh Avenue and 42nd Street—that famous old Walgreen’s that you used to see in the movies.

And I bought a spiral notebook, to use for paper. And I got a couple pencils and a plastic sharpener, and I did sketches. I turned in sketches the next day and finished art two days later. So I had my first job.

I have to say though, that Fact had gone out of business because Ginzburg got sued again, by Barry Goldwater. He had hired psychiatrists to analyze Barry Goldwater, so called, since none of them had ever met Goldwater or treated him or analyzed him. They were just giving their political opinions. And Goldwater sued him. That’s the reason that there is the so-called Goldwater rule I guess.

Steven Heller: And he won.

Brad Holland: Psychiatrists aren’t supposedly allowed to give their opinions about somebody’s mental health unless they’ve actually talked to the person and analyzed them. At any rate, what Lubalin told me was he wanted to publish a portfolio of my drawings because I had this whole portfolio of unpublished drawings that I had done while I was at Hallmark. And he said, “But you better talk to Ginzburg about that. And you better talk to him fast, because he’s leaving for prison next week.”

So I got an appointment to see Ginzburg, and he was indeed going to Allenwood, and he was looking for someone to edit his new magazine, Avant Garde, which is the publication that I did my first job for. Since I wasn’t ready to edit Avant Garde, he wasn’t particularly interested in me. And I said goodbye to him, and I never saw him again actually.

—

Steven Heller: When you finally got a place to live, it was on the Lower East Side.

Brad Holland: The first place was the Collingwood Hotel. I worked for two weeks in Times Square, and then I moved to the Collingwood Hotel on 35th Street, which is Little Korea now. But it was a hotel they said you could—this was great—you could rent it by the day or the hour. And you didn’t have to have any luggage.

I had a room that had been used by a prostitute before. And for the first month that I lived there I got for a discount because the lock on the door didn’t work. So every night I would push the bed up against the door—in case anybody tried to break in, I figured that would alert me. And I would feel all these calls for the prostitute who had had the room before me.

However, it did give me a telephone. There was a phone strike on in New York. And if I had gotten an apartment, I couldn’t have gotten a phone. So for six, seven months, I worked out of that hotel room. I went down to 23rd street and I got a great big drawing table. It was five feet by about four feet. I carried it on my back, back to the hotel. I didn’t have money for a cab, so I carried it in two pieces. I carried the drawing table on my back from 23rd Street to 35th. I went walking into the hotel lobby like some sort of laborer with this big, giant—it looked like a door, I think to most people—on my back. I got into the elevator, carried it up to I think the ninth floor I think is where I was living. And then I went back and got the stand and carried it back separately. So I had a drawing table and got some lights, and I was in business.

Steven Heller: And you were taking your work around the city?

Brad Holland: Yeah. I was taking a portfolio out every day. I was meeting an old girlfriend—or at least a woman I had dated in Kansas City—she came here to visit me for a week. She stayed at the, gosh, what was that an old hotel on 32nd Street?

Steven Heller: The Martinique?

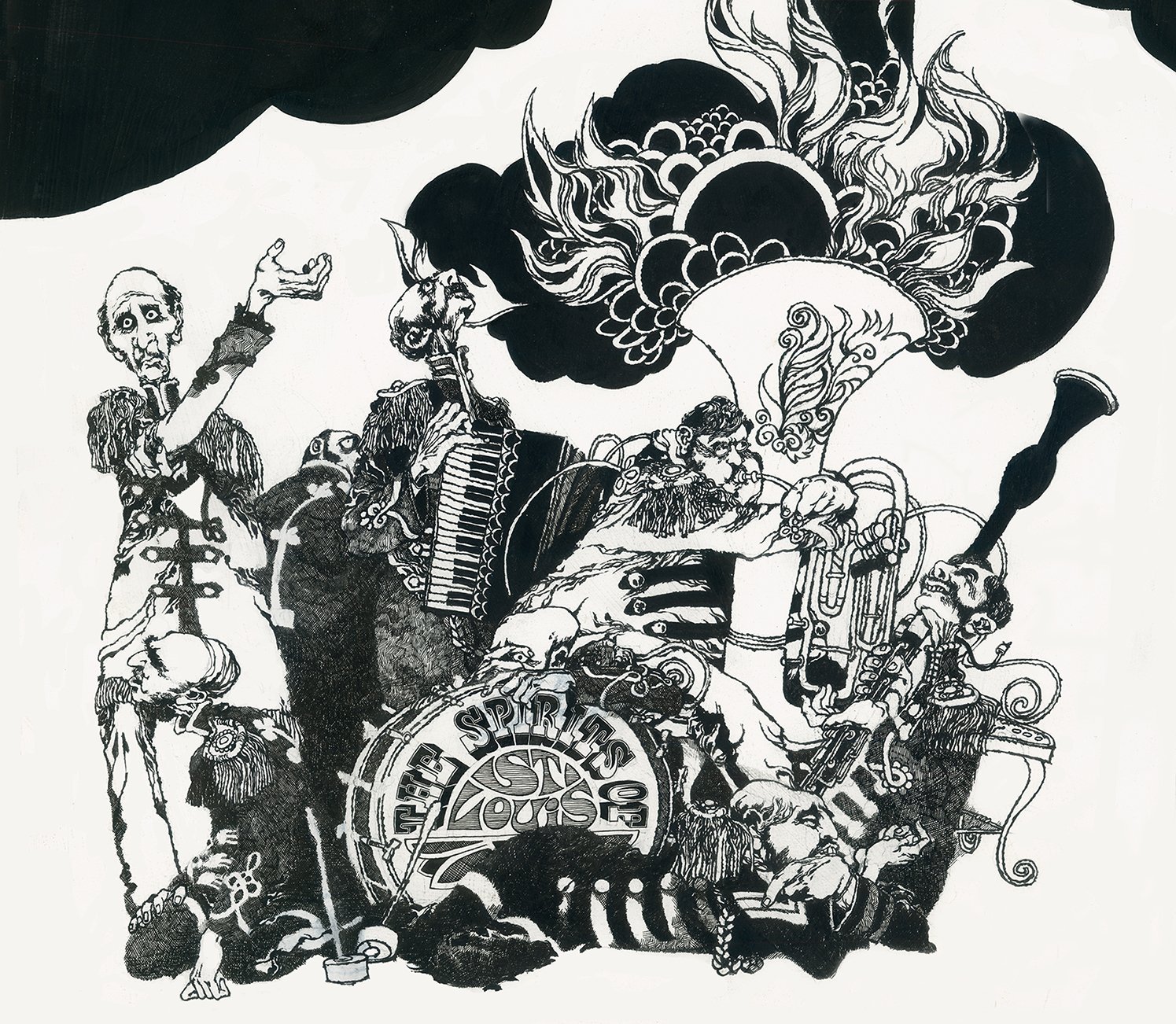

Brad Holland: It was an old, abandoned hotel that I think had been a big headquarters for the communist party once. And she was a very elegant college graduate. So I think I’d set her up in the wrong hotel as it turned out, but anyway, it was close to the Collingwood and we, spent the week together just traipsing around. This was the height of the 60s. It was the Summer of Love. The Beatles had just released the Sergeant Pepper album.

Everything was kind of a hippie culture… suddenly, you know, the word “hippie” had emerged just that year. The big song that year was A Whiter Shade of Pale, still probably the best song out of the 1960s, as far as I’m concerned. So it was a great week and we decided to meet again at Christmastime in Chicago, where I had some friends from when I worked there. So I decided I’d show my portfolio at Playboy while I was in Chicago. And that was how I got what turned out to be a 30-year run with that magazine.

Steven Heller: So you met Art Paul at that point?

Brad Holland: I went to Chicago and I visited my old employer, who I worked for for 18 months back when I was a teenager. And somebody there said, “Playboy’s looking for work like this.” So I took my portfolio up and dropped it off. And the next day I came back, and this beautiful receptionist said, “Mr. Paul would like to see you.”

So Art invited me in and asked me if I’d like to do work every month. And he said it was the most original portfolio he had seen in years and wanted to use me in every issue. Suddenly, you know, just months after going freelance, I was as secure as I needed to be for that stage of my life.

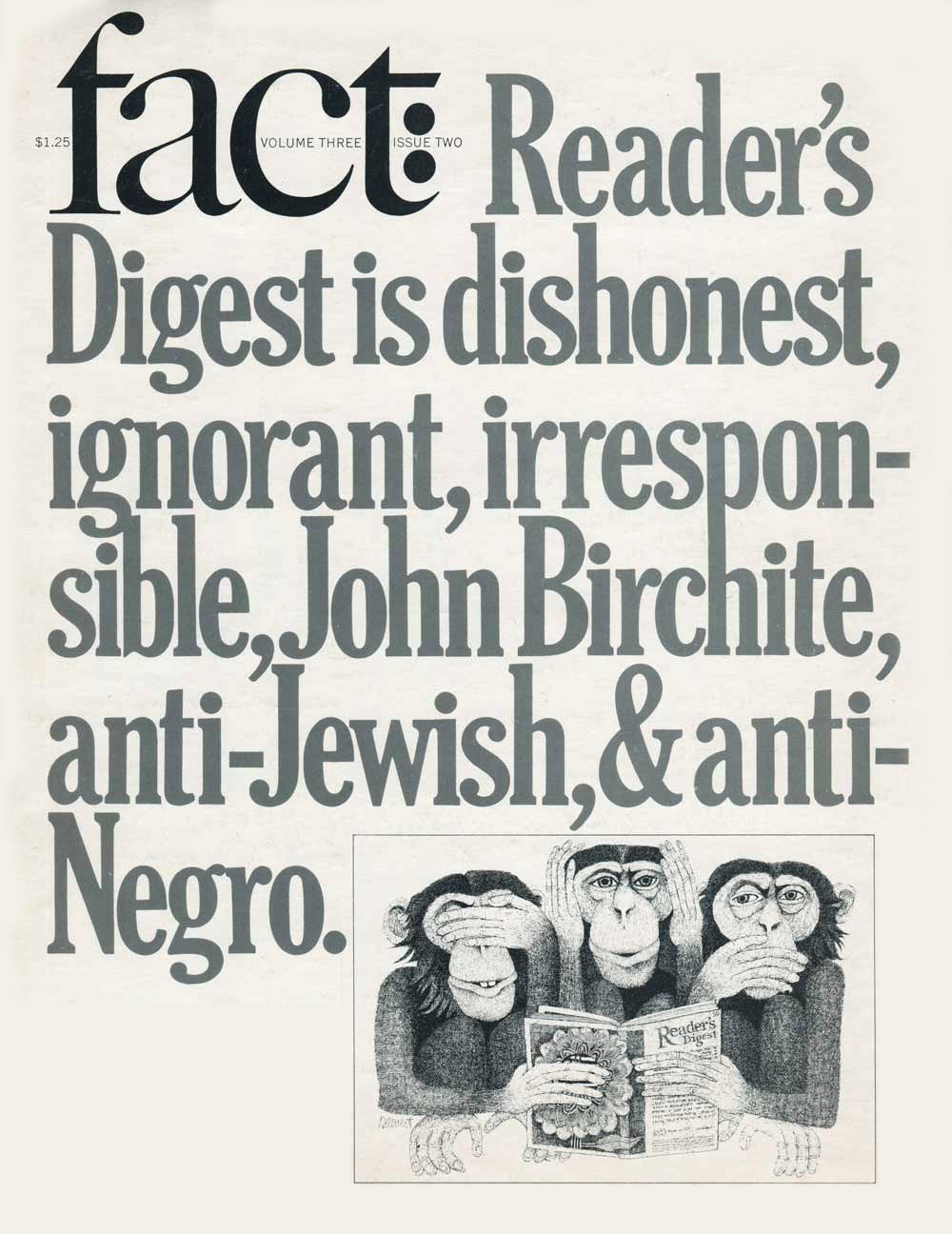

Holland’s portrait of Playboy art director Art Paul, and the sketch and finished versions of one of their first collaborations.

Steven Heller: So then you moved down to the Lower East Side?

Brad Holland: Seventh Street and Avenue C.

Steven Heller: It was an apartment that basically had hot- and cold-running people through it at all times. In terms of magazines, where did you want to be? What did you want to do for them?

Brad Holland: That would take longer to describe, and no one would believe it if I did. What I was looking to do was not magazines. I wanted to do books of my work. I really wanted to do books the way people do record albums. I wanted to just do a series of drawings and take them around to a publisher. It would publish them as a book. Well, that turned out to be a pipe dream, and I needed magazines to do work. So my concept then became, I found out, in fact, I found it out with my first job at Playboy. Art Paul had his assistant George Kenton call me with an assignment—it was a PG Wodehouse article. And I was so excited to get the work. It’s going to be a double-page spread. I was still living in the hotel at those days. This was just about a month after I’d shown Art my portfolio, right after Christmas. And George said, “We’ll send you your idea.” And I thought, “What do you mean?” You’ll send me my idea.? I thought artists did their own ideas. And he explained, no, that’s not the way it works. “We at Playboy, we come up with all the ideas and then we send them out to illustrators. We pick the illustrator whose work matches the kind of idea that we have.”

So I turned the job down.

I said, “If you ever can’t think of an idea, give me a call and I’ll do my own ideas.” So I, I turned the job down and then I started kicking myself because I was hoping that maybe if I turned it down they would let me do what I wanted to do. And I was badly mistaken. So for the next couple of days—it was January of ‘68—I started just walking around New York, kind of kicking myself for having overplayed my hand. And damned if two days later, Art Paul called me and he said, “Brad, I’m so disappointed. I hear you turned down our job.” So I thought, well, here’s my chance, now I can just say, well, yeah, send me my idea and I’ll do whatever you want.

And instead I did it all over again. I said, “I only want to do my own ideas.” You know, I said, “Well, what’s the point of doing ideas if you don’t do your own, or something like that, and Art explained why. He said “We can’t get illustrators to do the kind of work that—most illustrators want to do very literal work. And we can’t find people to do the kind of ideas that I want to see in the magazine.” And he said, “Do you think you can come up with a better idea than my staff?” And I didn’t know what the hell to say. Finally, I just said, “Well, I don’t know if I can do anything better, but I know I can do something more personal.”

And there was silence on the other end of the phone for just a fraction of a second, and Art says, “That’s a great answer, Brad. Go ahead and do something more personal.” And so I did, and I got my first job at Playboy. It was scheduled for the June issue. And in May I moved to the Lower East Side, counting on Playboy now for regular work every month.

And nothing happened. The magazine came out and there, the article wasn’t in it, my picture wasn’t in it. July came. Same problem.

Steven Heller: This was for the Ribald Classics?

Brad Holland: No, this was for the article by PG Wodehouse. It was an article about how he couldn’t get good servants any longer. He’s worried about getting good servants and I’m living in a room at a hotel that a prostitute found to be out of her league. So yeah, I wondered what had happened to the job in Playboy. I thought, well, surely they didn’t like it or something, They’re not going to run the thing. And I still couldn’t get a phone because the phone strike was on. So I went to a payphone.

I’d walk up to Times Square every day from 11th Street and Avenue C. They had a bank of payphones up there with big phone books that you could use. And I just went up there and I’d call every day. I’d make an appointment to show a portfolio, and then anytime anybody seemed interested in work, I’d have to kind of call them to say, “Any jobs for me today?”

It was very embarrassing, but the phone strike didn’t end until August. So I was, for three months, I was without a phone. And at one point I was so broke that I scrounged up five cents to go buy a candy bar, except the price of candy bars had gone up to I think to seven cents or something. And I was walking around the street, I found a $20 bill on the street, and boy did I live off that $20 bill for the next two weeks! I bought eggs and yogurt. And then all of a sudden, I called Playboy one day and they said, “No, no, no, Art loves the piece, but instead of running it in June, the way we schedule, we want to make a big issue out of it, and we want to run that along with a picture of you, in the December issue, and then start the Ribald Classics right after that.”

So I toughed it through the summer. I did a job for Redbook.

Steven Heller: Was that done for Bob Ciano?

Brad Holland: Bob Ciano gave me a job at Redbook I got enough money to buy a bed, and on the way home to the hotel I got followed. Most people think muggings occur in the middle of the night or something, but they don’t. They follow people home. And they get them in the vestibule of their building between one door and the interior door.

So I went in and, you know, stupidly, I collected my mail and these two guys come in with knives and they had me cornered in the vestibule and just automatically I tried to fight with them and I got my arm cut. So I learned, to look both ways before I entered the building after that, and never to enter a building. If anyone was 50 feet either side of the door. I never collected mail on the way in any longer. I just ran in and went to my apartment. But any rate I did manage to buy a bed. It was a used bed. I had a pair of box springs and a mattress, but now had a drawing table, lights, an air conditioner and a bed.

So what more did I need?

Steven Heller: You needed more clients, I suppose.

Brad Holland: I had a few clients, I was picking up work. I had already done work for do Gent, which was kind of an imitation of Playboy. There was Gent and what was the other one?

Steven Heller: There was Dude and Gent.

Brad Holland: Right. I don’t remember the art director’s name, but I did a very nice picture for them. $50. And I was doing work for Evergreen Review. I had started doing work for Ken Deirdorff. Ken was great. He had already given me several assignments, and they usually paid about $150 too, and I was doing some book jackets for Random House. They paid $150. I was doing work for Bob Sculladery. I went in and took him my portfolio, but I didn’t have any type on my work. In those days we designed our own jackets. We had to order the type. We got $150. We had to do three color separations, which meant doing three black plates and designating the colors to be used on each.

And we had to do our own type, and we paid for the type out of our own pockets. And since I had gotten my type connections from Lubalin, I was using the Composing Room, which was the best type house in town, but probably the most expensive as well. But I had a really nice catalog as a result of it.

So Sculladery had said, “Well, how do we know you can use type? “And answer was, “Well, probably I can’t,” but Jim Parkinson in Kansas City had kind of schooled me to the fact that there were different typefaces. He showed me this one has feet and this one doesn’t, and he told me not to mix sans serif with this, and not to mix Caslon with Bodoni, or something. So I had a kind of rough idea about type. I figured I’d just teach myself the rest.

“I’d seen ‘The Fountainhead’ while I was in high school, and Gary Cooper in that movie said that he would work for anybody as long as they let him do what he wanted. I saw that movie and I thought, ‘You know, that sounds right. That sounds about right to me.’”

Steven Heller: So, how did your strategy work? You would always say that you wanted to do your ideas, not other people’s ideas. There was a certain Ayn Rand quality to it.

Brad Holland: Yeah. Directly from Ayn Rand. I’d seen The Fountainhead while I was in high school, and Gary Cooper in that movie said that he would work for anybody as long as they let him do what he wanted. He designed garages for people in gas stations. I saw that movie when I was in high school and I thought, You know, that sounds right. That sounds about right to me. It’s right up my alley.

Steven Heller: And that’s what I thought when I met you and you announced that that was your strategy and preference. And we met at a friend’s house on East 10th Street, and his mother was an Ayn Rand-ist.

Brad Holland: Oh was she? I didn’t know that.

Steven Heller: She used to go to the Nathaniel Branden Institute every week and would take me with her.

Brad Holland: Oh, did you, go to some of those?

Steven Heller: I did go to some of those. So aside from the movie, and aside from the book, I got a mouthful of what you were doing.

Brad Holland: Ayn Rand was still around in those days. She had a half-hour program on WBAI in the mornings.

Steven Heller: So you were an iconoclast, among other things.

Brad Holland: I was just a Boy Scout from Ohio.

Steven Heller: You were a Boy Scout from Ohio, but you go in with demands to the art directors and editors. And you would tell me often about encounters you would have with the editors.

Brad Holland: [Laughs] They thought I was being arrogant. I was just trying to be—listen, here’s the deal: I was offered a scholarship to Ohio State in high school as a writer, and my high school English teacher, who had recommended me from, was very disappointed that I didn’t go into writing.

So I figured when I was in Chicago, see, I thought, when I went to Chicago, that artists were really artists. And they did what they wanted to do. I didn’t realize that the whole business of art broke down into fine art and commercial art. And if you did fine art, you couldn’t do anything realistic any longer, because that was—those were the days of abstract expressionism.

Picasso had said that after me, there can be no more realism because you can make wine from grapes, but never the reverse. And then along came out Reinhardt who was painting these black-on-black paintings and saying he was the ultimate artist. He had taken art as far as it could go.

And it couldn’t go any further. He had solved the problem, all the problems that had bedeviled artists for centuries, it was all done. It was all over. And the only thing now was to politicize art and start making art responsive to political needs. He didn’t go that far. That was what followed him.

My idea when I came to New York was if I couldn’t do what I wanted to do as an artist, I’d go into writing and do it there. And I just decided to make a kind of a make-or-break logic. I wasn’t trying to be an egotist. I just figured if I couldn’t do the kind of work I want to do, I’d rather do something else.

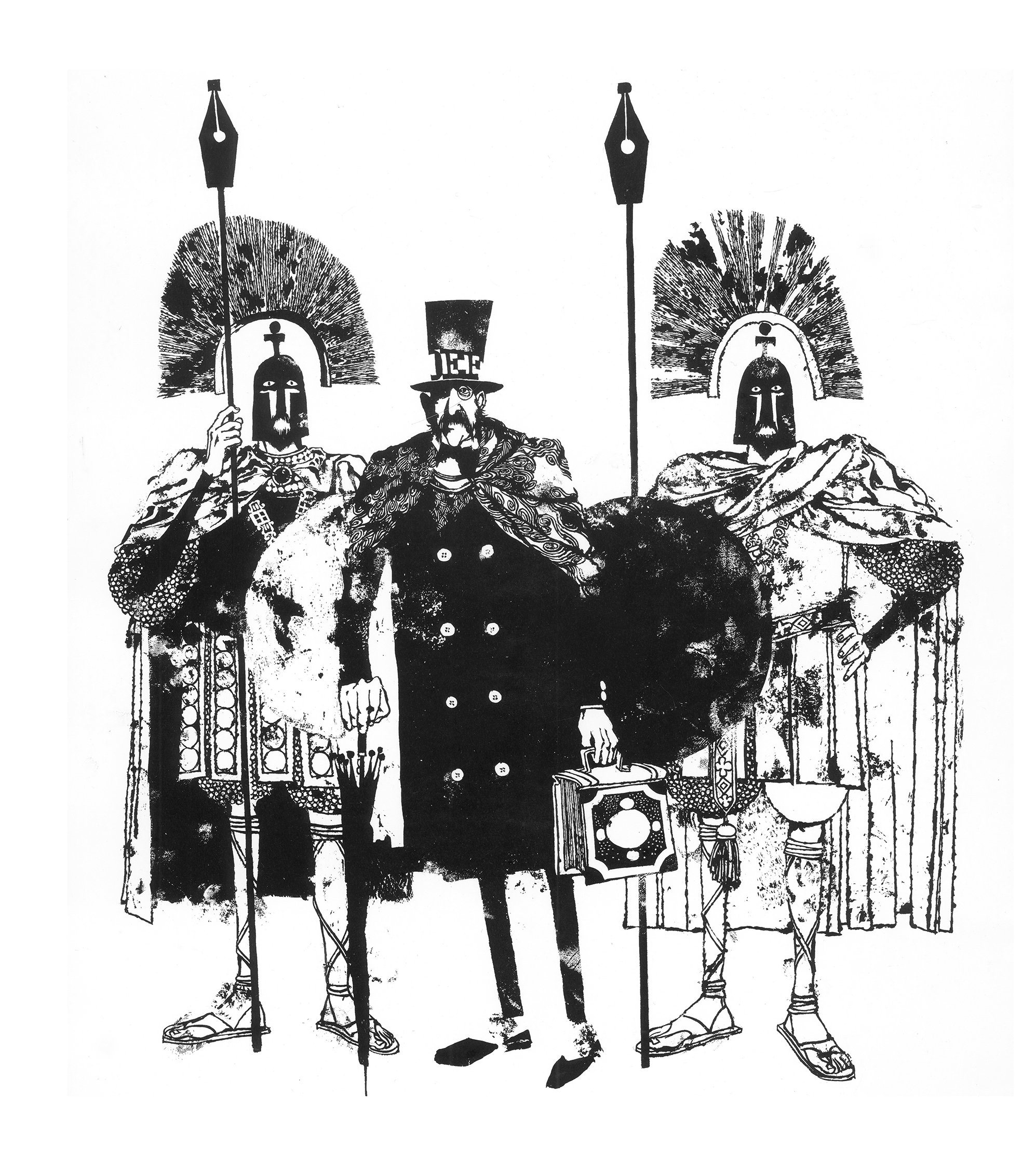

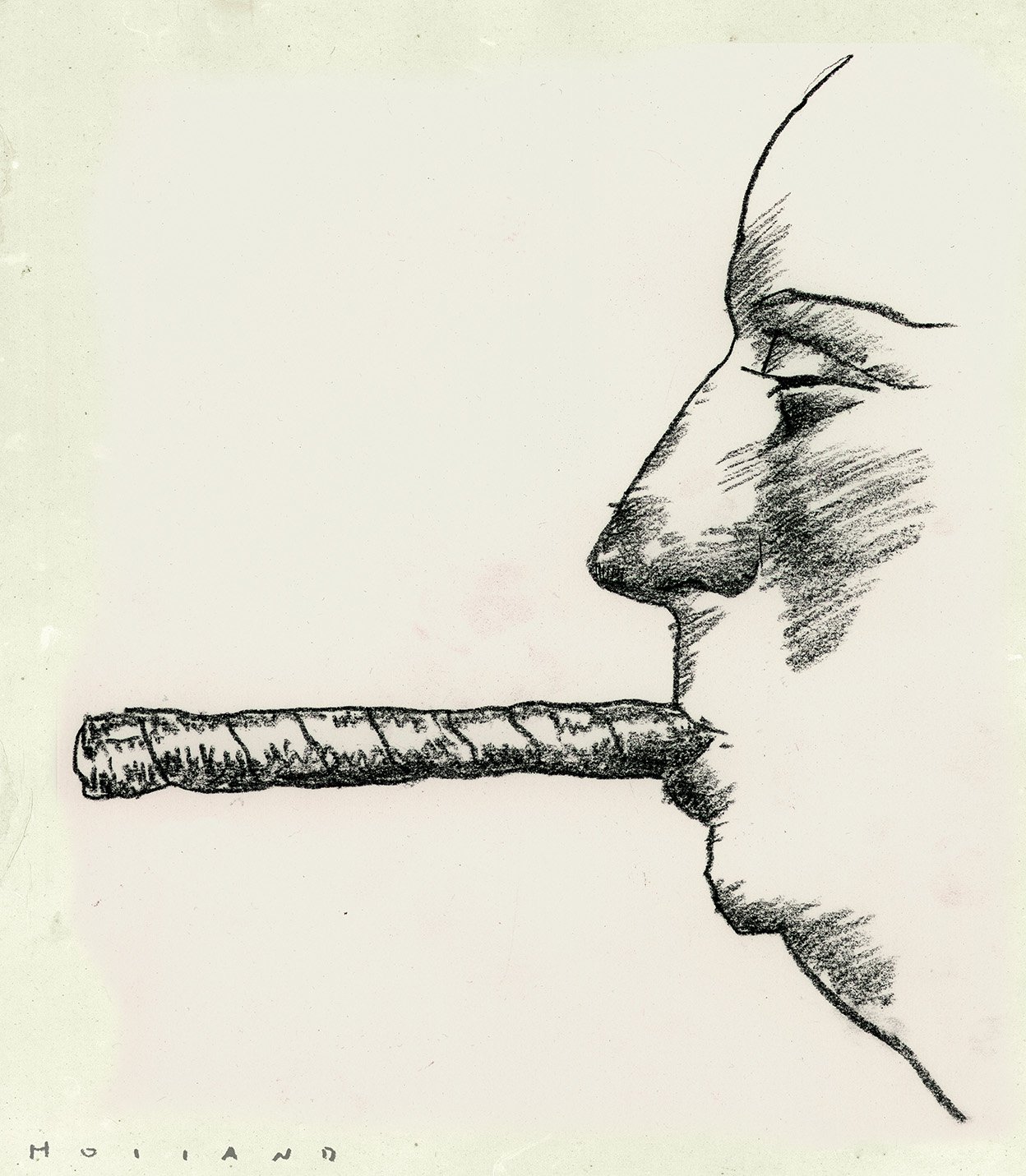

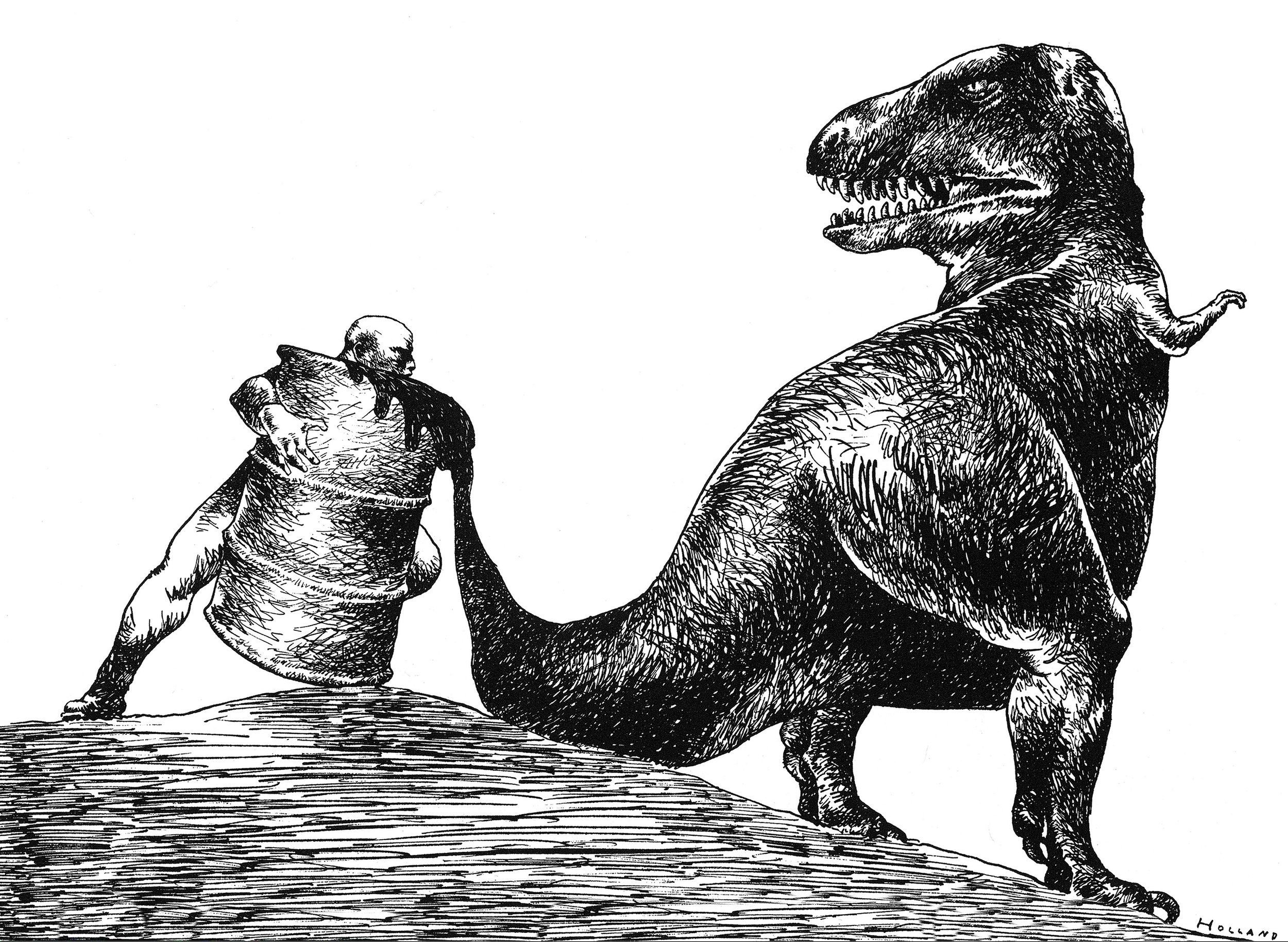

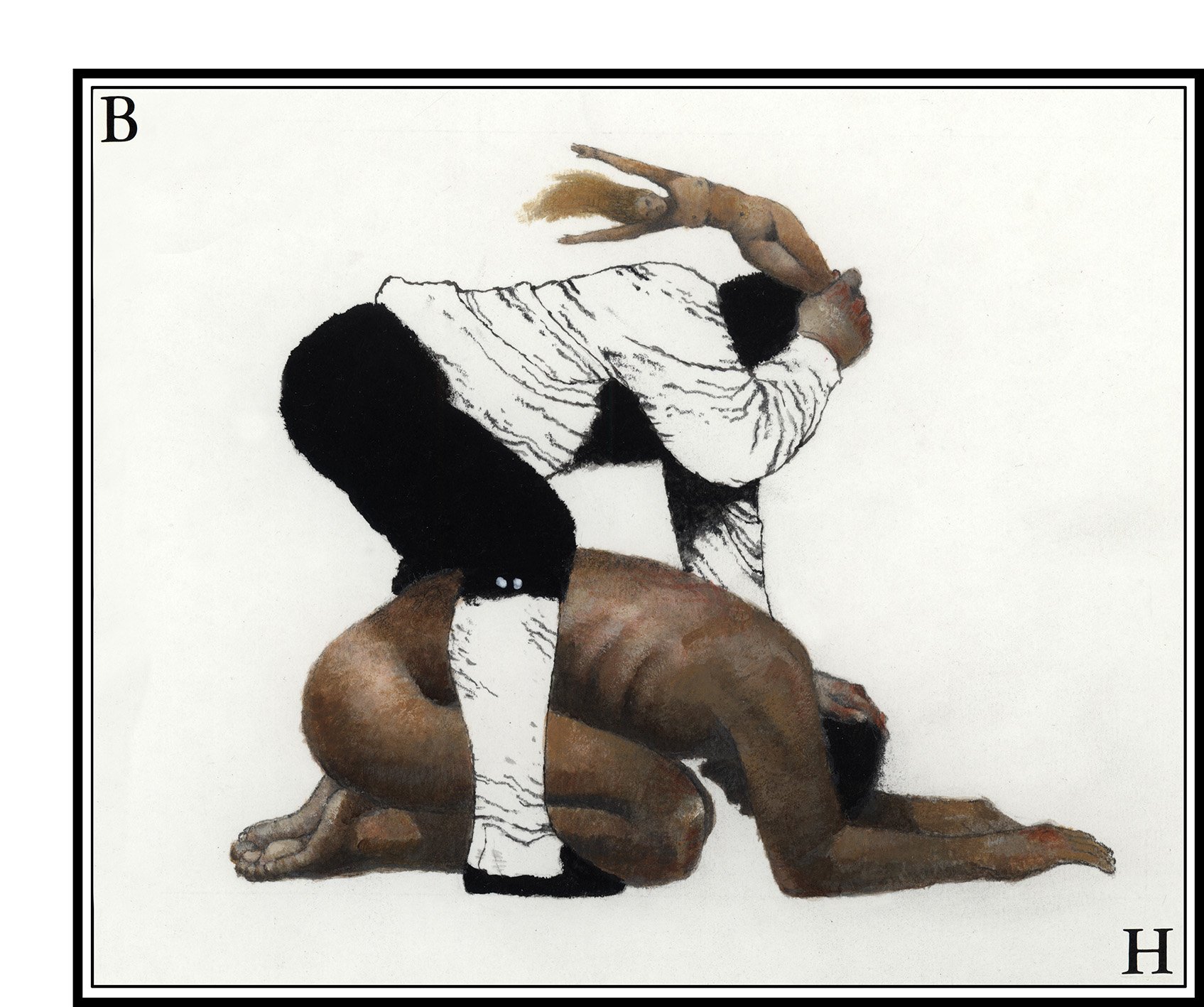

A selection of pieces from Holland’s first portfolio.

Steven Heller: So when you went to The New York Times…

Brad Holland: … I didn’t go, I was taken. There were three art directors who were responsible for what I wanted to do, making me successful. Herb Lubalin was the first, but I never worked with him again. Art Paul was the most important because he gave me this high profile in the highest-paying magazine in the world. I was getting a thousand dollars a month from Playboy, and that was 1968 money. I looked it up a year ago or when I wrote an article about it—it would be $5,000 in today’s money. So I was already getting the equivalent of $5,000 a month for doing one picture. And it was in a—you know, Playboy had a huge circulation in those days, I think it was over 6.5 million—so I had a huge circulation and a popular magazine, being well paid for it. And I never had to show them a sketch for any of those Ribald Classics ever. They sent me a job usually about three days before it was due. I’d do it in three days and send it back. And that was the way we worked for 20 years. It was a great relationship. At one point, Art began to disapprove, though. I began to start doing work that was a little too cartoony for Art’s taste. And he said so. And he rejected two pictures that I did. He was talking about getting rid of me at that point, if I wanted to keep doing pictures in that manner. And I said, “Well, no, I don’t want to do them in that manner that badly.”

So I went back to doing pictures the way I had been doing them. And he was right. Looking at those couple of exceptions now, I was trying too hard to fit into the hippie culture that I had become part of when I met you, because you were art directing—we met you were already art directing The New York Free Press. And I’d seen the ad. I was looking to get involved in the hippie papers and I had The Village Voice, and I saw that ad that you would run. I called you up, and you told me to meet you at this apartment. So I got there.

And here were a bunch of kids who had just graduated from college or from high school acting really cool and kind of eyeing me like when I used to catch the bus east from Arkansas. I would get on a bus that had come out of Los Angeles and switched—the Ozark Stages would connect in St. Louis. But by the time I got on the bus, it was headed east from California, and everybody on the bus had been on board for like a day and a half. They all knew each other. And I’d get on in St. Louis and everybody looked at me like the new kitten in the litter. And that was kind of the way you and your pals looked at me that day when I showed up with this big portfolio and all these pictures.

Steven Heller: Well, I think it was the largest portfolio anybody ever saw.

Brad Holland: But the pictures were big. I needed a big portfolio. So at any rate, yeah, we did that job. We did your publication, the one that you did with your bar mitzvah money. And in the middle of it, your art director friend quit. And you and I ended up on the floor of my apartment pasting up ads. I tried to find a bunch of illustrators to do work for it. And I said I was going to just kind of bring some people into it. I got some friends and I said, “We’re doing this magazine and I just want you to do whatever you want to do.” Well, at this time, I already had the idea that we would get pictures that were separate from the articles.

I mean, this was the reason I wanted to get into the hippie press: Every magazine that I was showing my work to wanted to art direct me. And I figured, well, maybe the hippie press will be different because you know, everybody’s making it up as they go along there. And if I get in there, maybe I’ll meet some young people who will become art directors, and then we can work this thing out. You guys were more my age than the art directors I was working for. Most of the art directors I was working for were in their thirties or forties, and you were just a few years younger than I was. So I figured I would be more with people my own age, if I got into the hippie press. Because I was still 23 when we met.

Steven Heller: But you were working for glossy magazines.

Brad Holland: Yeah, I had worked for Redbook by then. And Redbook was a big magazine and one of the highest-paying publications. Redbook and McCall’s were run out of the same office. And McCall’s was that place where Bernie Fuchs was making a huge splash in those days, doing all those Kennedy articles and so on. McCall’s was one of the highest-paying magazines in the world as well. And Redbook was kind of the little sister publication. But they were high quality.

“I wanted to work for Walt Disney, you know. I’ve written about it. I applied for a job at Disney when I was 16, got rejected when I was 17. And then I figured I’d have to go to plan B. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a plan B, so that’s when I got on the bus and went to Chicago and figured I’d just make it up as I went along.”

Steven Heller: So was illustration for you a “quintessential” art?

Brad Holland: No different than I would’ve treated fine art if I’d gone into fine art. I had no art education when I went to Chicago. I wanted to work for Walt Disney, you know. I’ve written about it. I applied for a job at Disney when I was 16, got rejected when I was 17. And then I figured I’d have to go to plan B. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a plan B, so that’s when I got on the bus and went to Chicago and figured I’d just make it up as I went along. I did apply for a job at Disney one more time while I was in Chicago. Got rejected a second time.

So then I figured I would just go into a fine art, and that was when I found out that fine art was supposedly a very different thing. If you were an illustrator, you weren’t doing anything important. If you were a fine artist, anything you did was important. This was the era of the topless cello player. Remember Charlotte Mormon? I think she began playing the cello topless, and by the time she was finished, she was playing the cello naked. But this was the era of topless, cello players, and self mutilators. And I figured that if this is what art is all about, I don’t want anything to do with it. And in the meantime, I had gone beyond Norman Rockwell, which is what I thought of illustration.

In Chicago I had the great Chicago Art Institute where it was free admission during the day, and I worked downtown so it was only about six blocks from there. I’d walk over during lunch hour, and lunch hour could last all day because we didn’t have much work at the studio. We’d usually have to do paystub jobs at night. But during the day, I’d wander through the Chicago Art Institute. I saw Rembrandt’s etchings, which I thought were ink drawings. I didn’t know what etchings were. I saw Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, which I didn’t like. I thought it looked unfinished. I didn’t realize he would later be one of the biggest influences on my painting style, but it began there. I saw Winslow Homer, whose paintings I’d seen in encyclopedia. At that age I couldn’t have told Michelangelo from Leonardo. I was that ignorant of the fine art world.

Steven Heller: I seem to remember you were in the Brandywine School as well.

Brad Holland: Yes. I was very big on the Wyeths. Although I liked N.C. more than Andrew, and he was a big influence.

Steven Heller: So take us to the Times, because that is where…

Brad Holland: … Well, it began with you because you were doing The New York Free Press when it morphed into Screw, and you were Screw’s first art director. So how did you feel when you learned that the Free Press was folding, or it was in decline at any rate, and Goldstein and and what’s his name, Jim Buckley, were starting the sex paper of which I have to say was, this was predicated on the fact that there had been a Supreme Court ruling about a movie, a Swedish movie called I Am Curious Yellow, that showed intercourse on the screen for the first time. And the Supreme Court ruled that it wasn’t pornographic. So what happened at the New York Free Press that got you into becoming a pornographer?

Steven Heller: Being 17 and not knowing any better. I wanted to do cartoons and you wanted to publish in the Free Press, and I told you that only I could run…

Brad Holland: Yes, you were the only artist to be in the Free Press.

Steven Heller: But then we started the New York Review of Sex, and you started doing drawings that looked very much like the Ribald Classics, except with a little more genitalia.

Brad Holland: Yeah, with quite a bit more. In fact, some fairly large. You had asked me what I wanted to do with the new magazine. Steve’s being modest. Steven art-directed Screw until the Free Press folded and what the Free Press had become—which was basically a neighborhood, leftist newspaper—kind of morphed into the New York Review of Sex, which to give it its true name was the New York Review of Sex & Politics because it was basically the New York Free Press with what they used to call “tits and ass.”

So it was masquerading as a sex paper, in which it ran articles about brothels in Saigon—that was a way of getting into the Vietnam war articles. And then there weres coverages of gay bars. This was before the Stonewall, in fact Dan Mauer and I went down to the Stonewall one night before the riots to get in. And we were supposedly doing an article. I was going to do some drawings, Dan was going to write the article. Dan had just come back from Vietnam. And the two of us went to the Stonewall one night to check in and spend a little time in there. I don’t know whatever became of the article. I never did any drawings. But yeah, I did drawings for the New York Review of Sex & Politics.

When you asked me what I wanted to do, I said, “Well, just give me a quarter of the editorial page.”

And you said, “Well, what would you do with it?”

And I said, “Well, I’ll do whatever.”

And you said, “Fine.”

So that was the way we started that one. You were the second in the league of art directors who just let me do exactly I wanted to do. And I did it for, I think, what were you paying? Fifteen bucks?

A sampling of Holland’s pieces for Playboy. Many of these pieces were used in the 1986 Kim Bassinger/Mickey Rourke film, 9 1/2 Weeks.

Steven Heller: If you were lucky we paid you. [Laughs].

Brad Holland: Well, I did, four drawings for Screw under four different names that made it look like you had four different artists. I did an Edward Gorey-style drawing. I think I did a Jack Davis-style drawing. I did one of my own, and I may have done a Leonard Baskin drawing. I can’t remember.

Steven Heller: You did a number of Leonard Baskin drawings.

Brad Holland: A lot of Baskin drawings.

Steven Heller: So how did the leap to the Times happen?

Brad Holland: Well, after you left Screw to work on the Review of Sex & Politics, which later added “Aerospace” to the title since the editor had been a paratrooper. It was the New York Review of Sex & Politics & Aerospace. Do you remember the slogan for the newspaper?

Steven Heller: “A Symptom of our Times,” right?

Brad Holland: It was The New York Review of Sex & Politics: A Symptom of Our Times, which is a way of saying, “Sorry for all the naked pictures, but we have to do it in order to get readers.” That was essentially the way the paper functioned.

Otherwise, it was very political.

So anyway, as far as JC Suares, who had been your boss when you signed on after high school to edit—Steve should be telling this himself but he’s going to be too modest to tell it—Steve graduated from high school when he was 17 and got a job working for the Free Press as a summer job.

And JC Suares was art directing the thing. And JC had just come out of the Army himself and was doing drawings very much like David Levine and art directing the Free Press. Steve got this job and Suares got a better job and left overnight! So Steve was left learning to art direct The New York Free Press kind of on his own and just making it up as he went along.

So when Steve started art directing—Steve, when you started art directing the New York Review of Sex & Politics, Suares came back to art direct Screw, and he has also got a job moonlighting, or maybe “sunlighting” might be a better word, for The New York Times, working kind of day jobs at the time.

And you all had moved into 80 5th Avenue and Screw moved just down the hall from us. So Steve and his crew were in an office on one end of the hall in New York Review of Sex & Politics, and Screw was down on the other end producing Screw. And the two rival sex papers were running out of the same floor, and people were running back and forth between the floors, and Suares came in one day, mostly, I think, to just kind of razz Steve and give him a hard time. And I happened to be sitting there, and Steve introduced us and he said, “Oh, I’ve been, you know, I’ve been following that work you’re doing in Playboy. And one day, he came in and he said, “Hey, how would you like to do for The New York Times work like you’re doing for Playboy?”

And I said, “Yeah, sure,” thinking he was just making it up, but damned if he didn’t, you know, the next day we were headed up to The New York Times.

Suares was the only art director in the hippie press who drove a Bentley to work. He had two of them. And he was very much offended if you referred to one of them as a Rolls Royce. Bentleys, in his mind, were superior to Rolls and he definitely had a Rolls.

He was not making the money from Screw. I have to mention that he was a descendant of the banking Suares family in Alexandria, Egypt. And they had left the country during the Nasser revolution back in the fifties. He had gone to Yale, and, I think, dropped out and then went to Pratt because he wanted to be an artist. Anyway, he took me up to The New York Times and introduced me to Harrison Salisbury. They were just starting the op-ed page, and Harrison asked me how I saw my work being used, how I saw illustration being used on the op-ed page, because they had never run art on the editorial page before.

Holland’s portrait of a young Steven Heller, his long-time friend and collaborator.

Steven Heller: It has to be said that the op-ed page existed because Lou Silverstein started it, and used people like Ralph Steadman, along with other European artists.

Brad Holland: Did he use them before Suares?

Steven Heller: He used them before Suares, and Suares was a good choice because he was already fluent in that language of European illustration.

Brad Holland: I came in with Suares so I attribute everything to him.

Steven Heller: So when you came into the op-ed page, there was this overlay of surrealist work, all linear —his studio, in fact, Suares’, was called Data Studios.

Brad Holland: Yeah that’s right.

Steven Heller: So he had that sensibility.

Brad Holland: Oh yes. Suares had a definite background in all that.

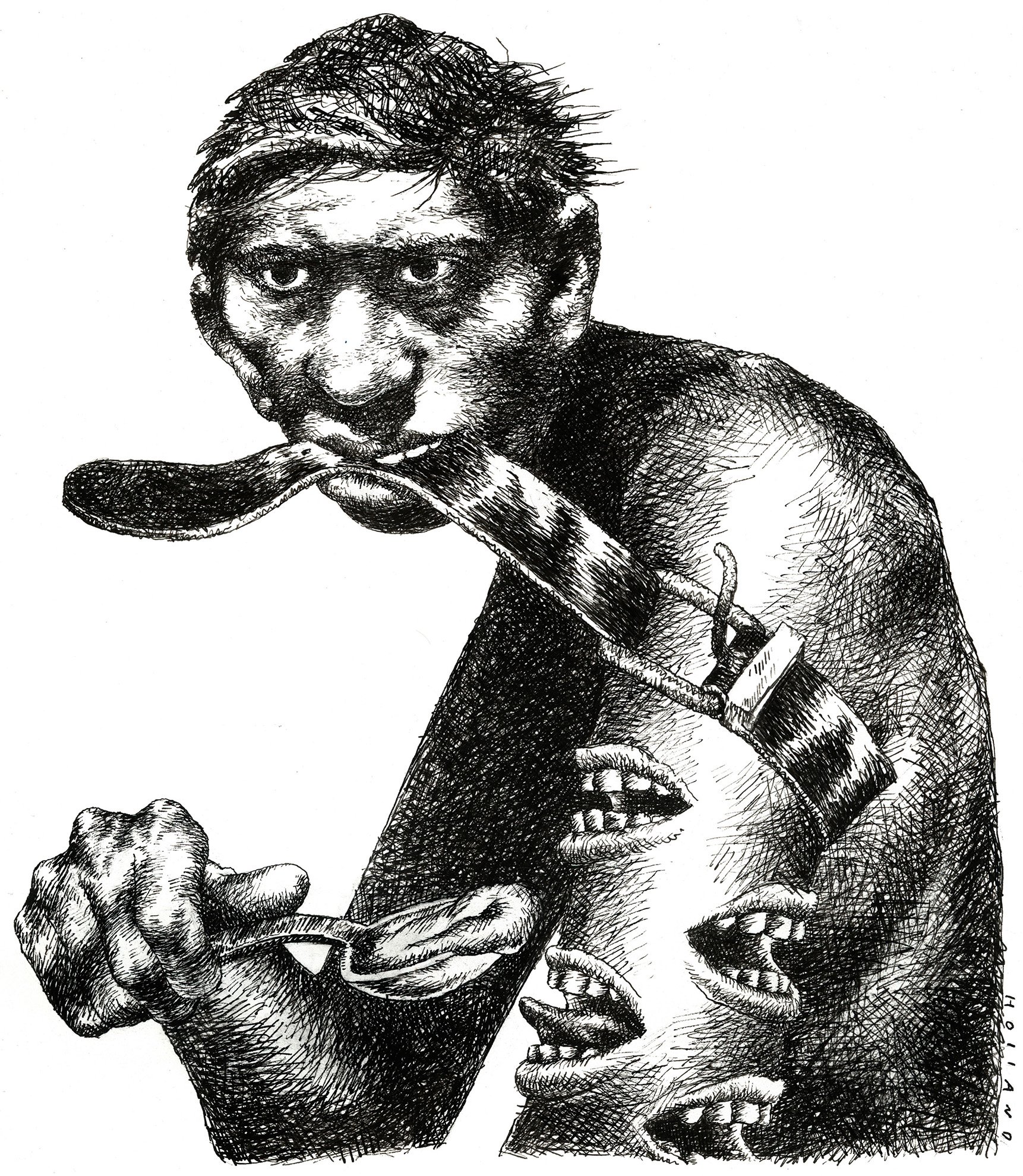

Steven Heller: So that’s when your work began to change. You were doing that kind of comic strip, R. Crumb-related stuff, and then it kind of morphed into what I consider the first link, the junkie drawing—the junkie drawing with the mouths and the arm.

Brad Holland: Yeah, that was one of the first drawings I did. Harrison asked me how I saw my work being used. He called it illustration, and I said, well, I don’t really think of it as illustration. I didn’t know what to say. And I kind of stammered around for a second. And then I thought I had a great angle. I said “Just imagine that you lock the writer in one room and the artist in another, and you give them both the same assignment. And then you put this stuff together.” The writer gives you an article, and the artist gives you a picture, and you just put them together. As long as they run tangent to each other, that qualifies as a direction.

I’d never used that line before but I began using it after that. The example I always used to use when I was arguing with art directors about it, I said, “Take the most famous illustration in Western art, which would be the picture of God, creating Adam on the Sistine chapel ceiling.”

And I said, “Why does it not illustrate the story?” The story has God breathing life into Adam. It doesn’t have them touching fingers. Why did Michelangelo paint God breathing life into that? Because on the Sistine chapel ceiling, it would look like a kiss and it wouldn’t have given the impression that Michelangelo was trying to convey. But everybody who’s ever petted a cat in the middle of winter knows that sparks jump. Or when you shake hands with somebody and static electricity jumps, or when noses come too close in dry weather, just before a kiss, a spark will jump. And Michelangelo must have recognized that and turned the breath of life into the touch of the hands. And I said, I don’t know, a single person, art critic, preacher, anybody who has ever criticized that painting because it doesn’t illustrate the biblical language.

Everybody takes it for granted because the Hebrews, when they wrote the Bible, were using a verbal metaphor: God breathes life into a person. And so that comes from the belief that when you die, you breathe your last breath. So if the breath leaves your body, signifies your dying, it must’ve been the breath of life coming in from God.

It was a perfect metaphor, but it was a verbal metaphor. And what I was looking for was visual metaphors that didn’t simply imitate the verbal. And so, for example, once I had a job to illustrate a glass ceiling, and I did a picture of a guy who was climbing a flight of steps, only when he got to one step, the next step was too big. A step that he couldn’t have made. It was a glass ceiling, except there was no glass ceiling. So I took it into the editor and he said, “The article’s about glass ceilings. Where’s the glass ceiling?” I said, “It’s glass, you can’t see it.,” and then I tried my Michelangelo story on him.

That way, I, began to explain at least to some, that what I was looking for was a visual counterpart to whatever verbal information they had in the text. I began with trying to explain it to Harrison that day, because over the first year or so, I was having a hard time explaining what it was that I was trying to do besides being a jerk, which is what some thought I was just being.

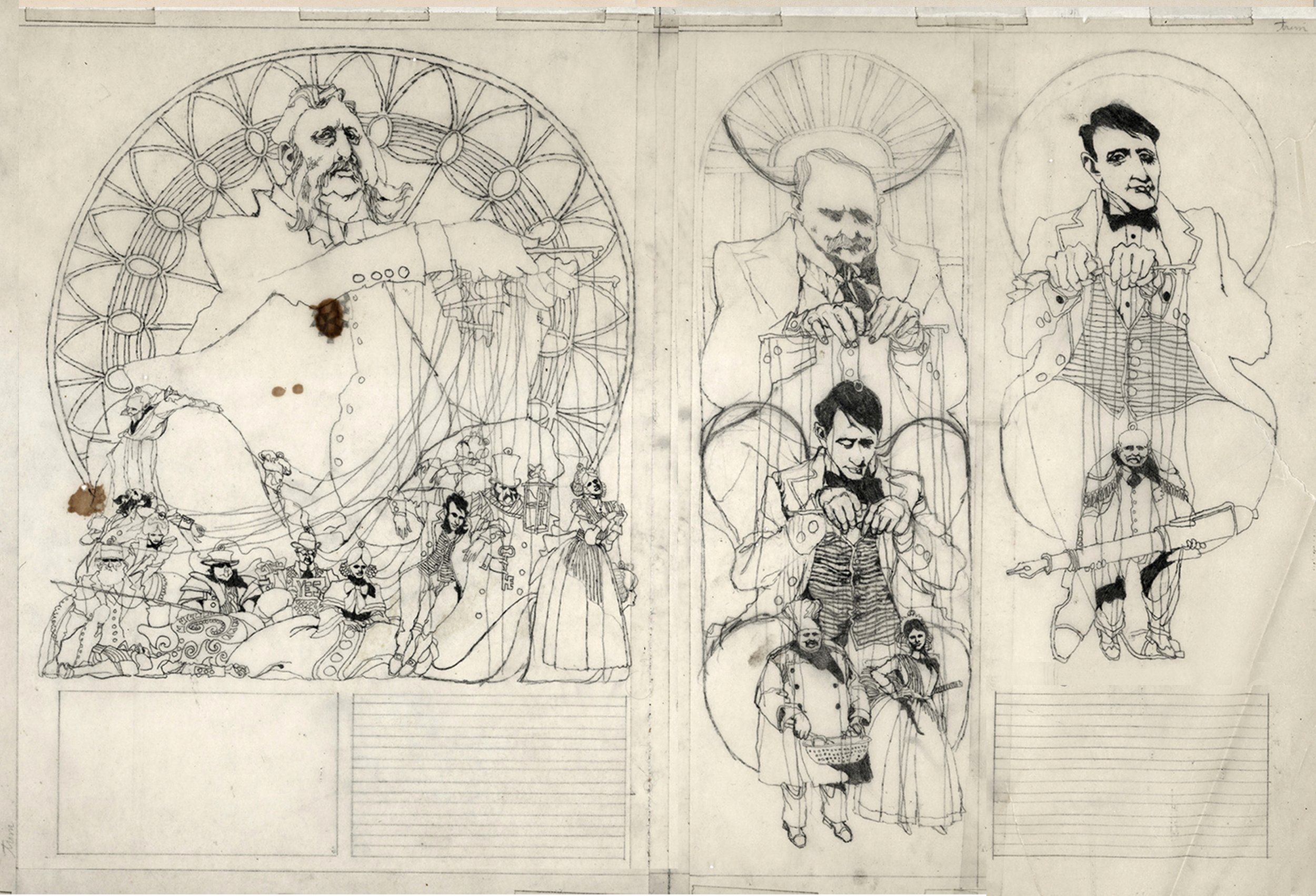

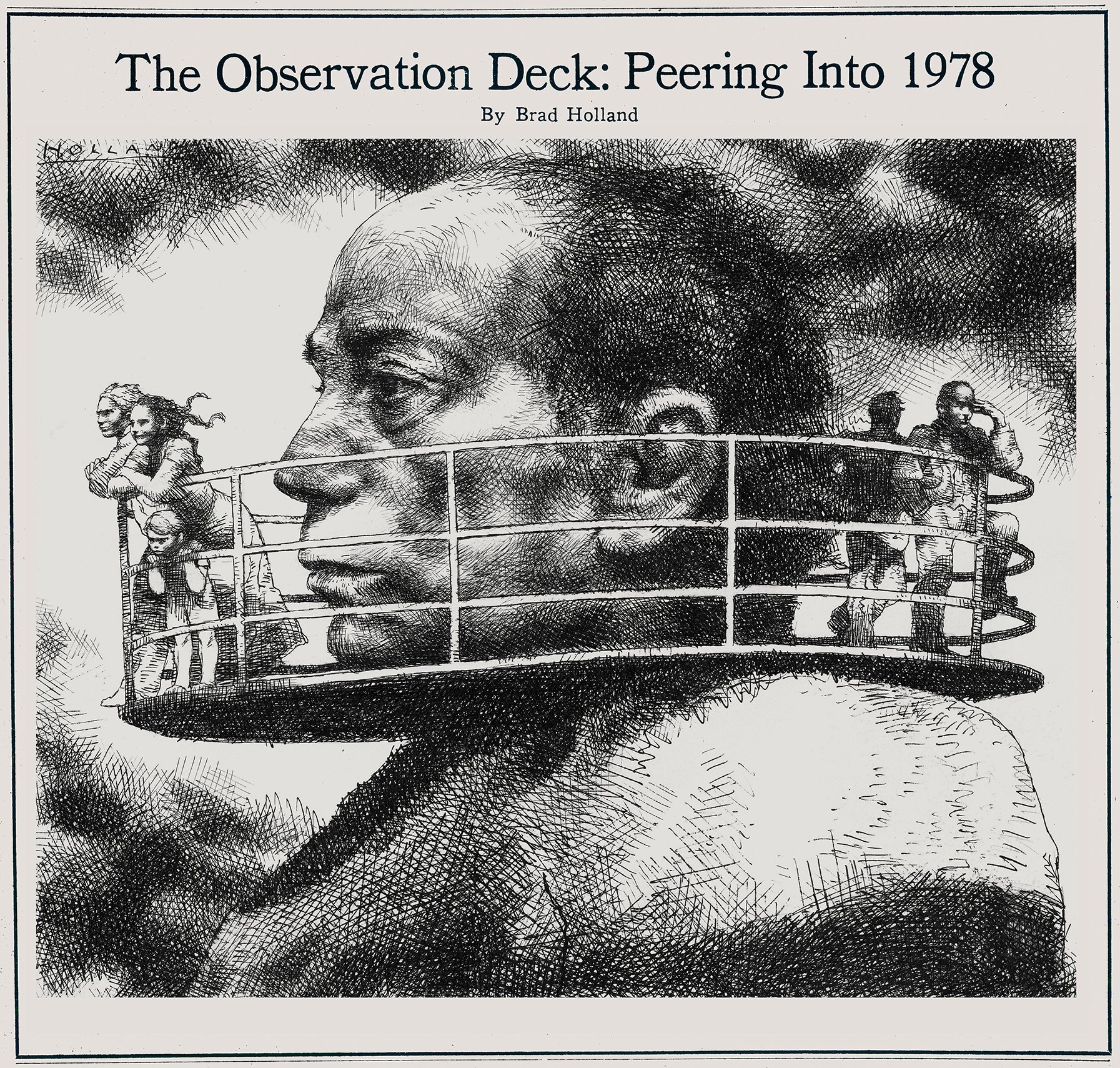

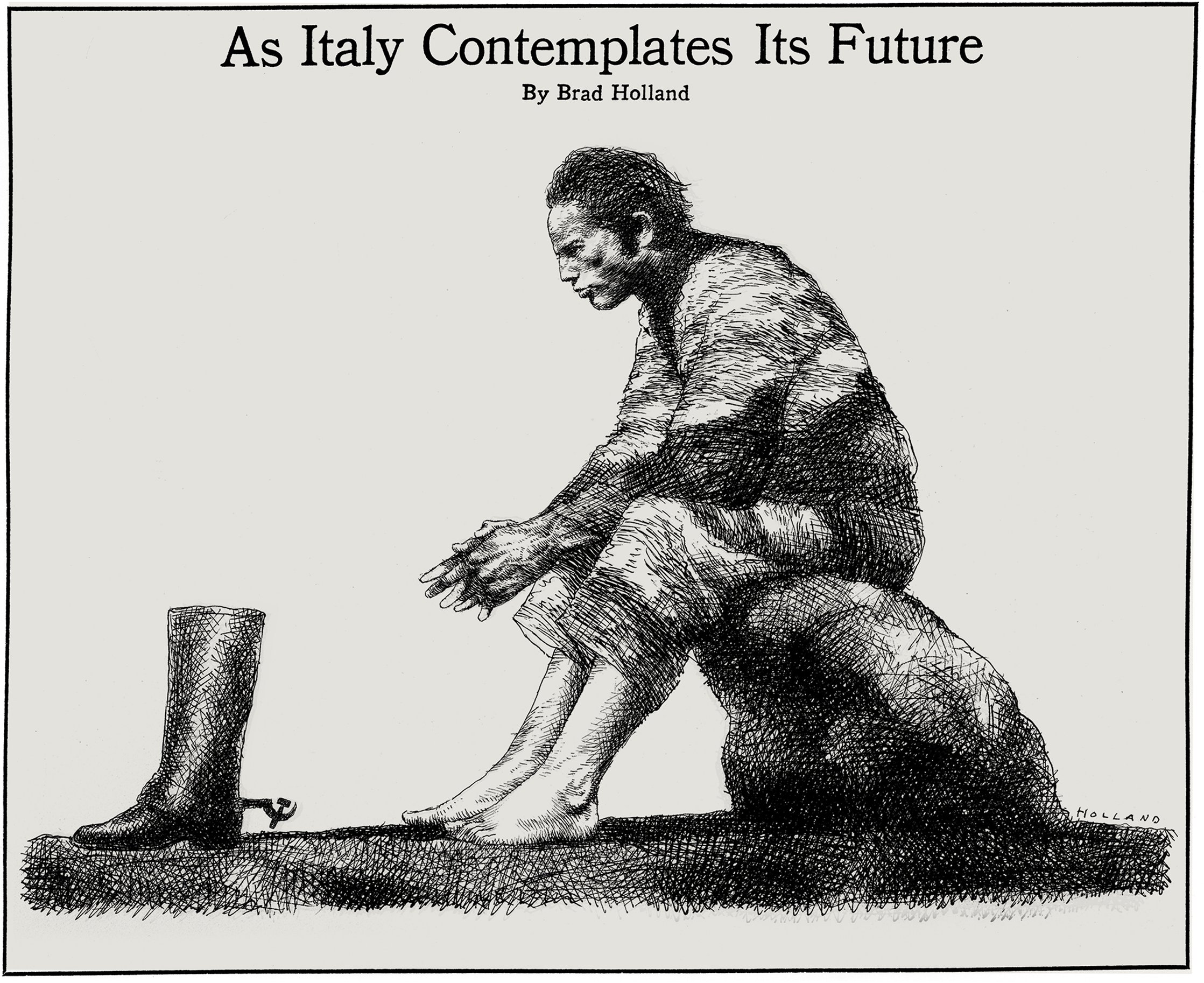

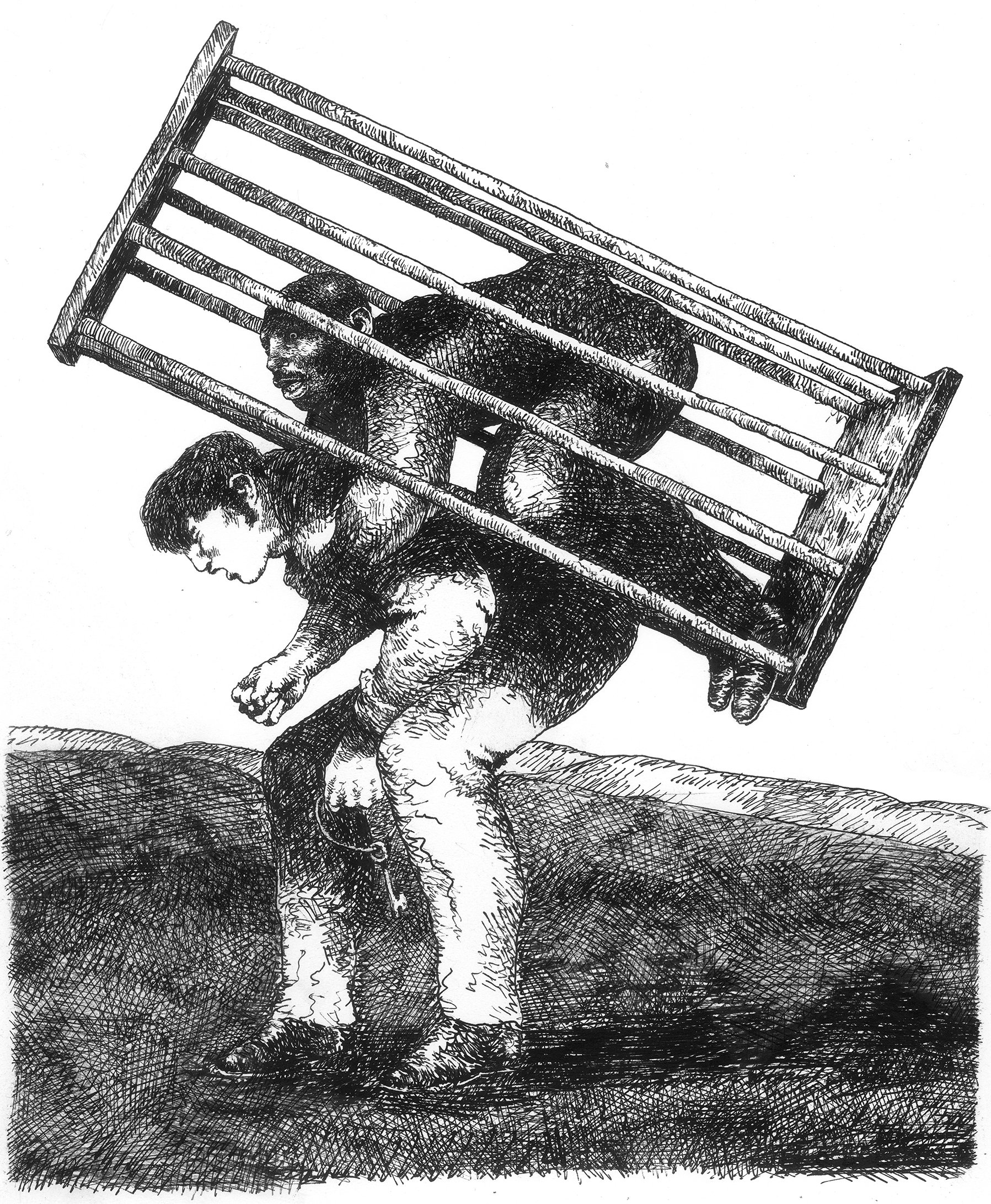

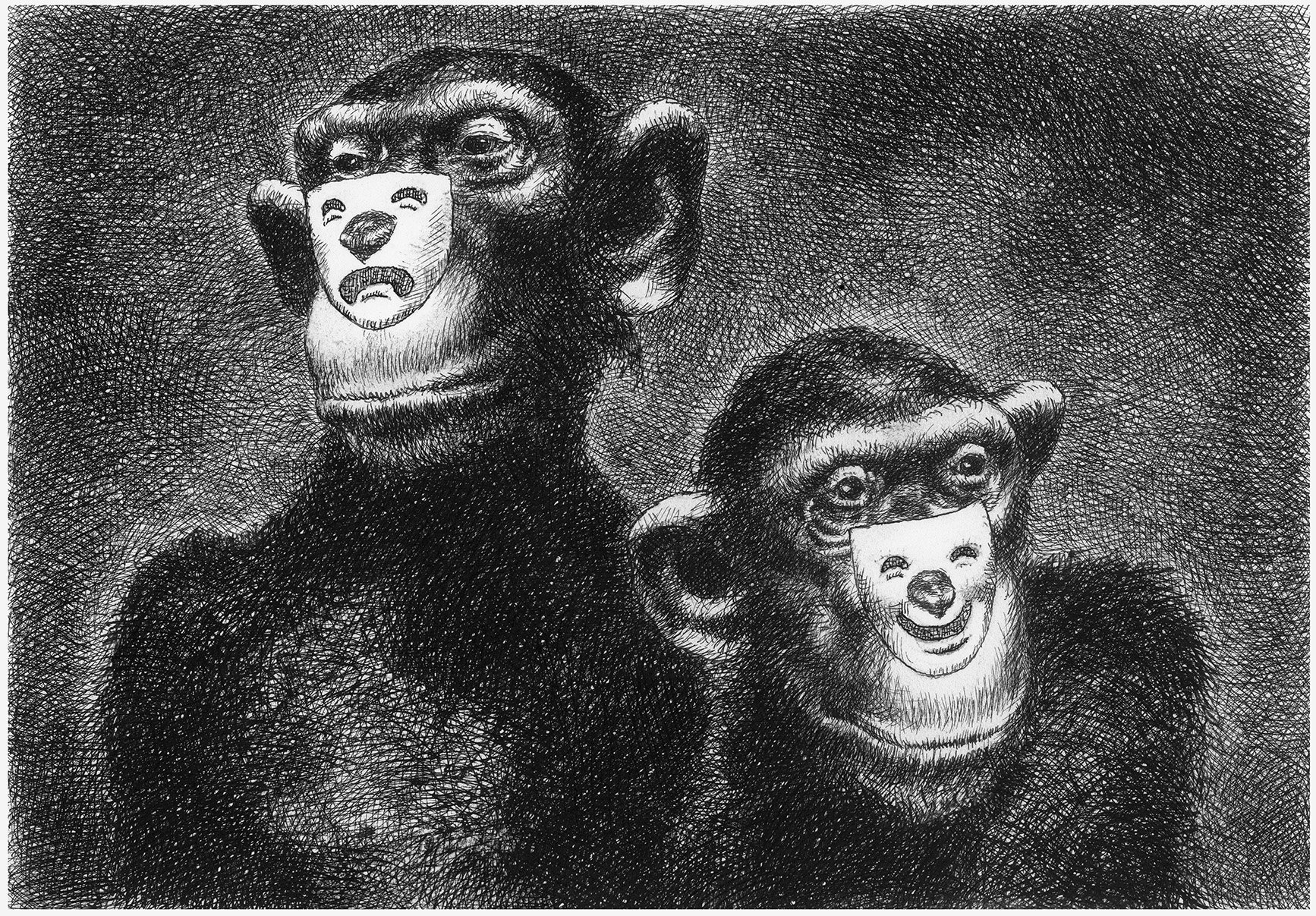

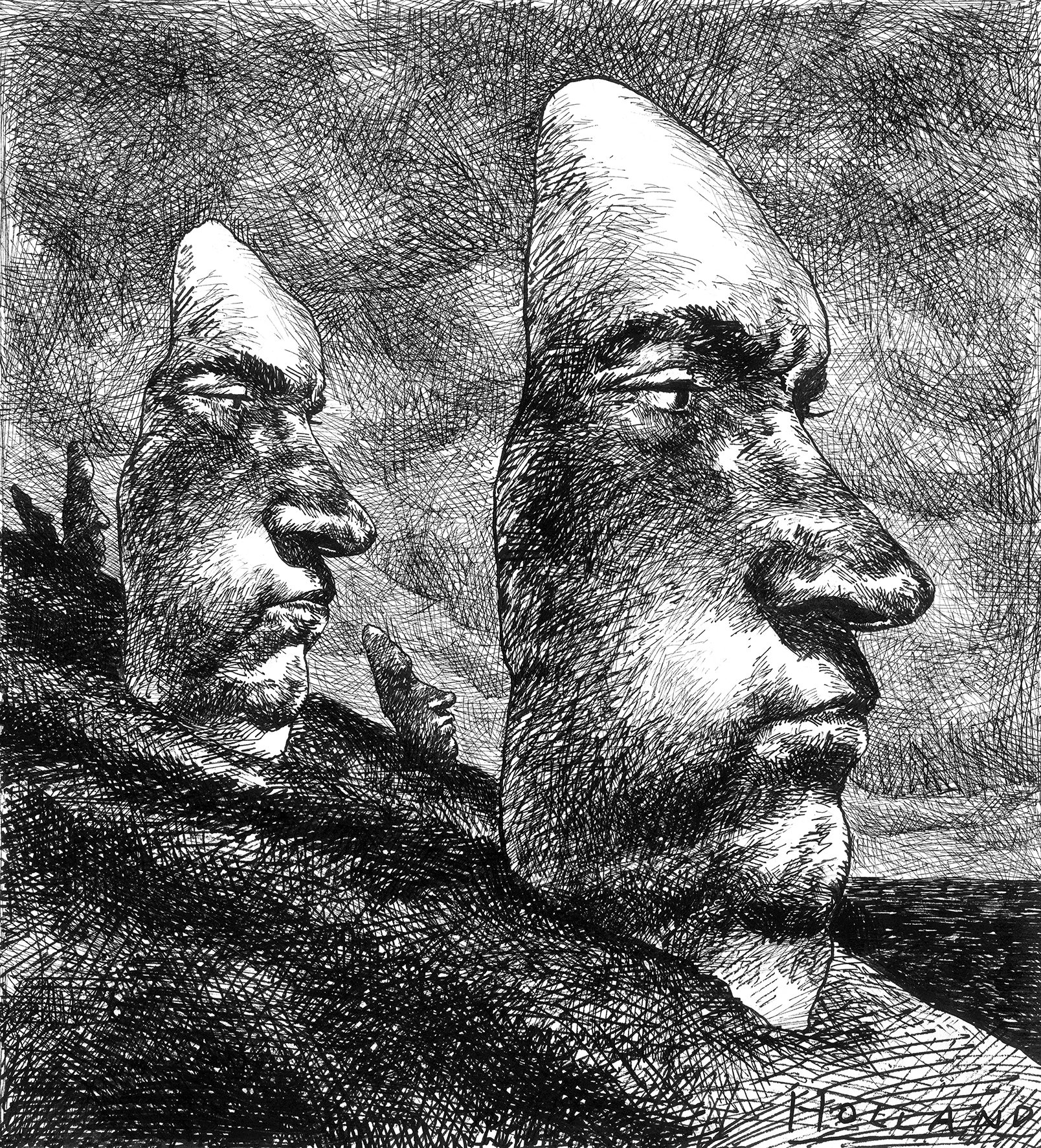

Holland’s work with JC Suares for The New York Times Op-Ed page.

Steven Heller: So the op-ed page allowed you to follow that strategic idea, that philosophical idea that you had.

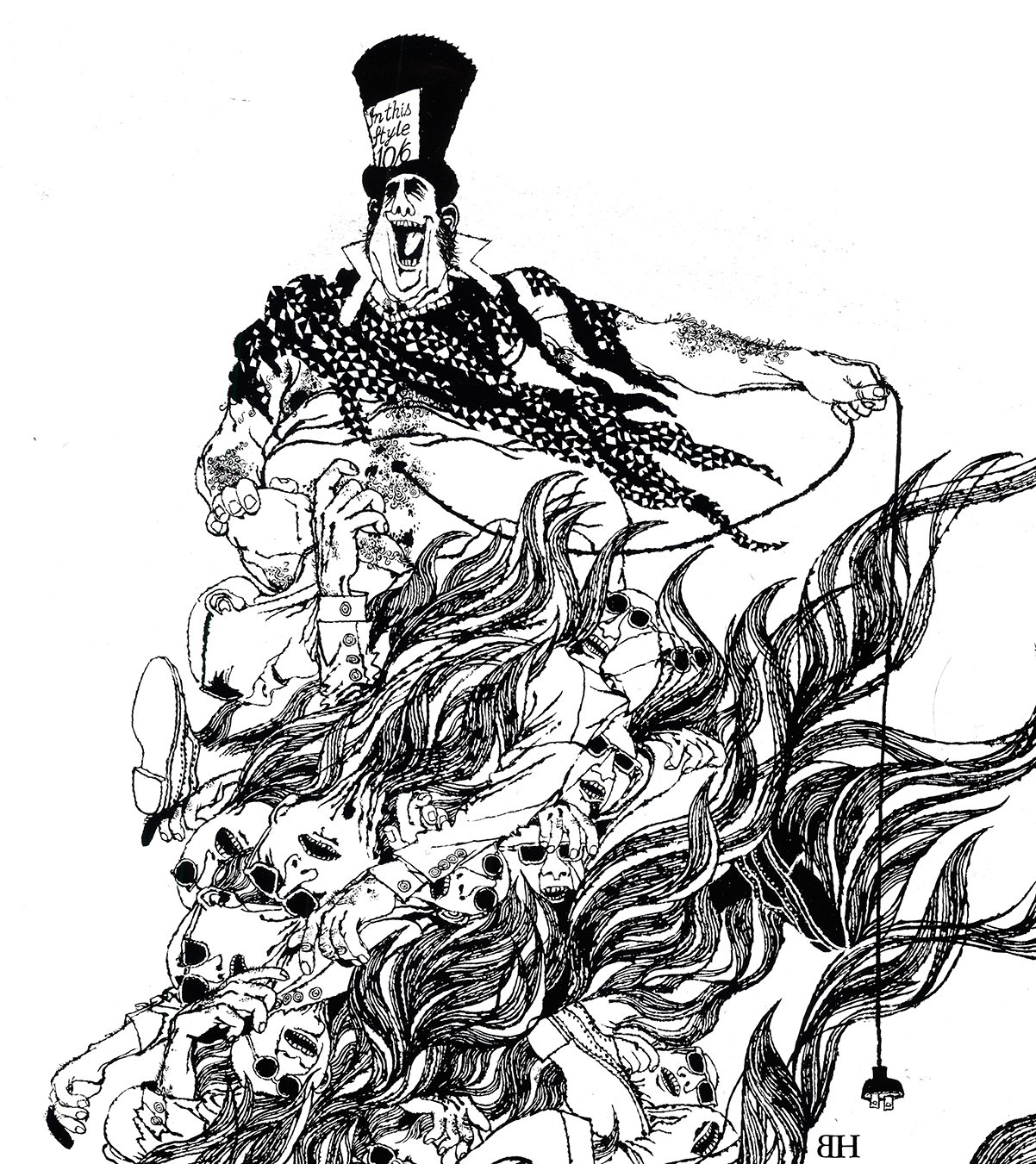

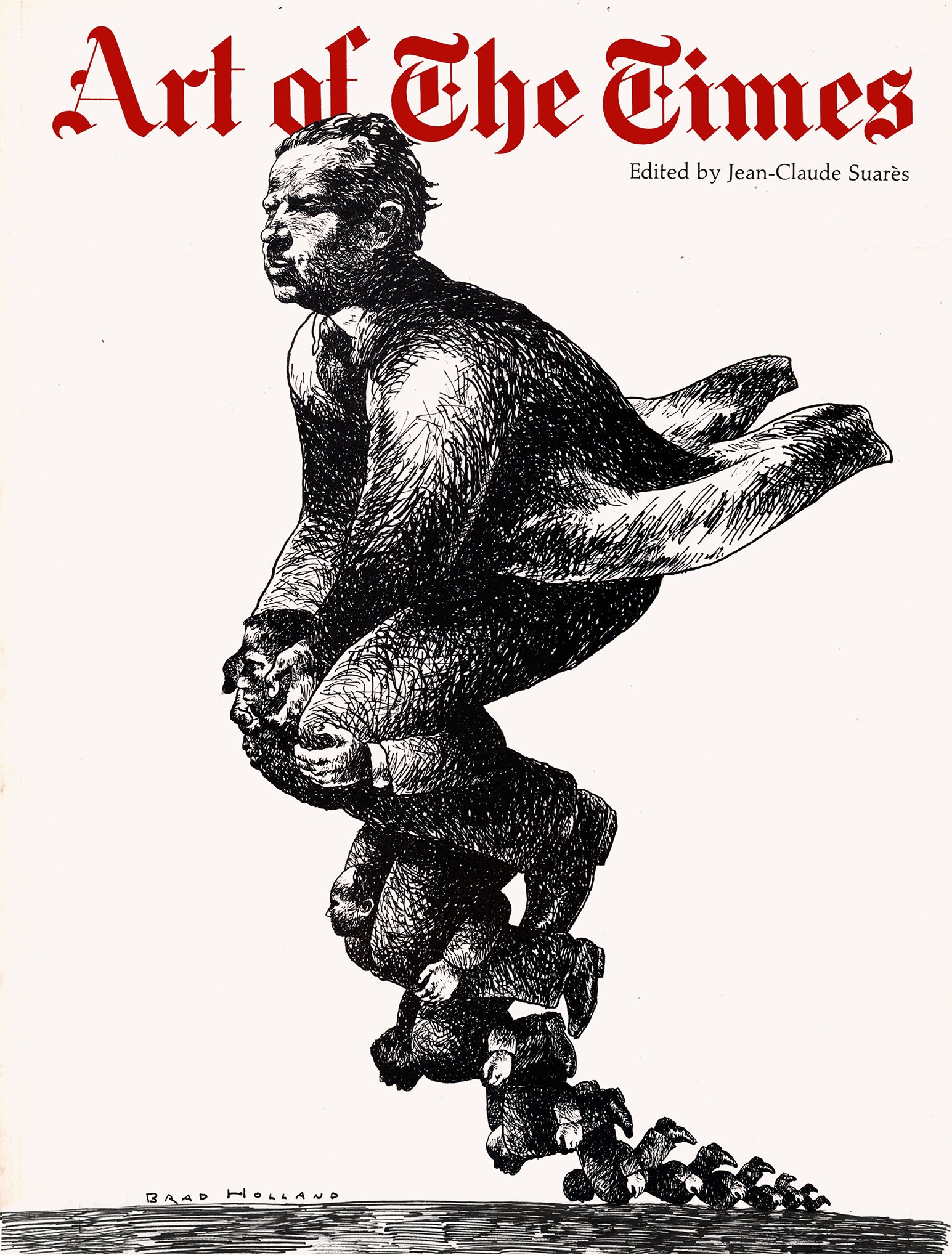

Brad Holland: I did pictures. Well, for one thing, Watergate came along and with Watergate, I didn’t have to follow the story. In fact, the story evolved so fast that usually by the time story was written, there was too little time to do a picture, just, to go with it if you wanted to get it out overnight. So I began just doing pictures following the news. One week I did four different pictures about Watergate. One of them was Nixon on a top of all these subordinates—each subordinate was smaller than the one above him. Nixon was at the top, Halderman right under him, Ehrlichman right under him, John Dean, right under him. And I didn’t know the rest, so I made them all generic, but each one got to be so small that they were eventually just a chain of people collapsed. it was used on the cover of the first catalog of op-ed work. It was one of three drawings I did that week. And I just took them all up to the Times and dropped them off, and they just applied them to articles as the articles came in.

So I didn’t read a single article for any of those pictures.

Steven Heller: When I first went to the Times as art director of the op-ed page, you gave me three books. One was Kathe Kollwitz. The other was Heinrich Kley. And I think George Gross was the third.

Brad Holland: I don’t think so. I didn’t like George Gross. It would likely have been Baskin, but I couldn’t promise that. I know I tried to get you to write to Baskin to get…

Steven Heller: Well I did, and I got him to do stuff for us.

Brad Holland: Yeah, he did Nixon and who else?

Steven Heller: He did Ford.

Brad Holland: Oh yeah, he did Nixon and Ford, and he did them on the back of other drawings. And they were about a year after you wrote him the letter, you wrote him a letter. It took a year for him and he sent a letter back along with a picture of Nixon and a picture of Ford drawn on the back of some other drawings that I guess he discarded. I was trying to get you to use all kinds of people like that.

Steven Heller: When did magazines start to change in terms of your own work?

Brad Holland: Well, what made a big difference was when we had that show in Paris and The Art of the Times book came out, because my work was on the cover of that. The Art of the Times came out around the same time as The Art of Playboy, because Playboy had a traveling exhibition called “Beyond Illustration” that Art Paul was doing.

Steven Heller: That was at the Huntington Hartford Museum.

Brad Holland: Well, that’s where it came, but it had traveled around Europe first. it was previewed over there. And one of the pictures that I had done for Playboy was used as a poster for that, and then came The Art of the Times book, which came out and my drawing was on the cover of that. So from that point on, people kind of came to me for the kind of work I wanted to do.

One of the things that I did early on when I worked in Chicago, I was looking at portfolios of the kids who came to our studio, looking for work. They’d show us these portfolios. And they had Time covers and record album covers, and the guy I was working for John Dieszecki, he made a point of saying, “Don’t show this kind of stuff, because everybody knows you didn’t do Time covers, your work doesn’t look like it’s ready for Time. You should be doing small jobs. Do a catalog for a small company that nobody’s ever heard of and show that in your portfolio.” I took that idea to heart myself, and when I did my portfolio, I did all black and white work, except for a few color things that I had done at Hallmark. I showed almost all black and white, and the idea was that most people relegated black and white to spot illustrations. And I learned at Hallmark that editors don’t pay a lot of attention to work that they don’t think is important. And so I figured I could break in by doing work that most artists didn’t want to do.

And I would take the smaller jobs and usually get to do them in the way I wanted. I think it worked out. That was part of my strategy: to take the smaller jobs and do them the way I wanted. So after a while I had a portfolio of things that looked like I wanted to do them.

And pretty soon I began getting calls to do that kind of work.

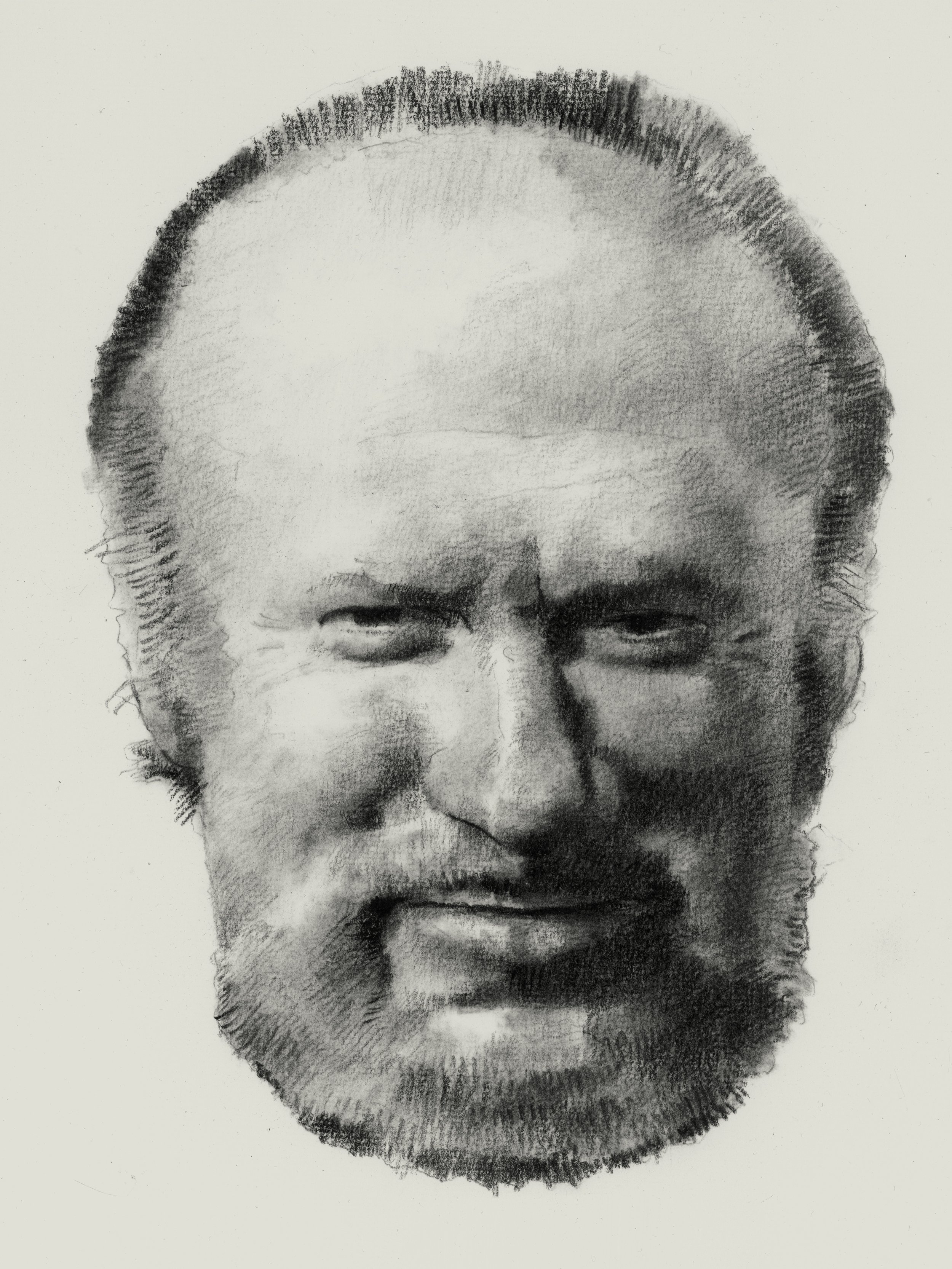

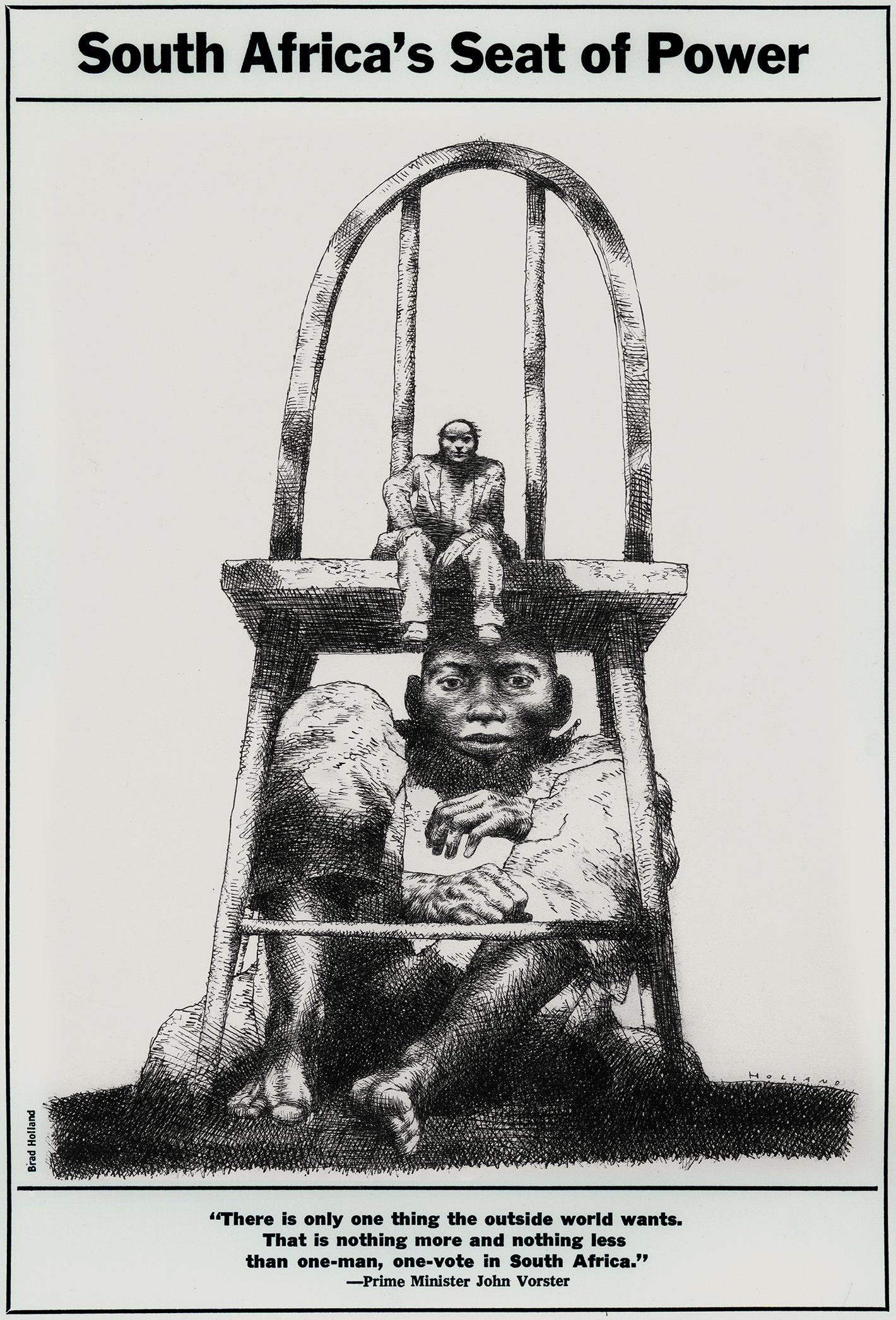

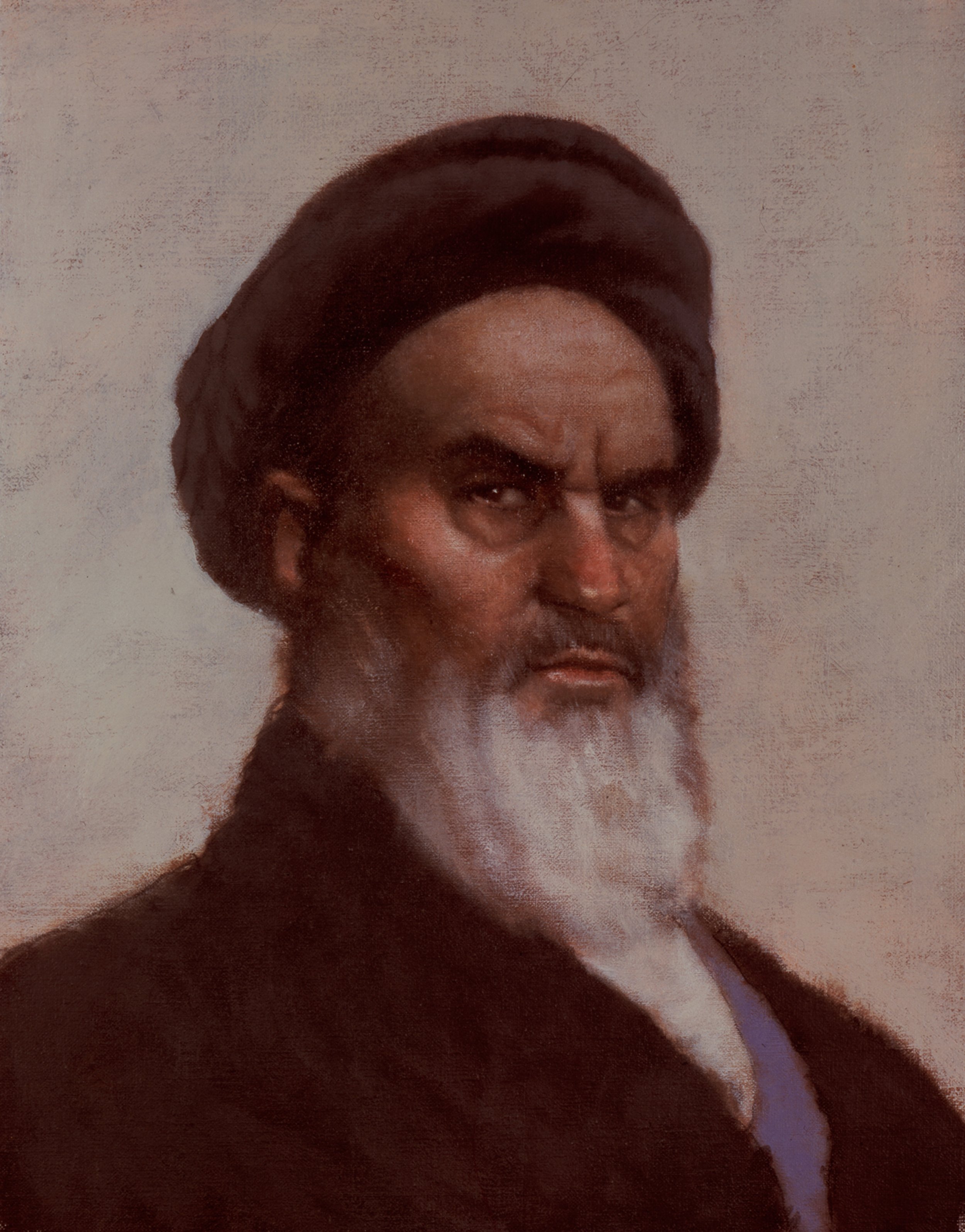

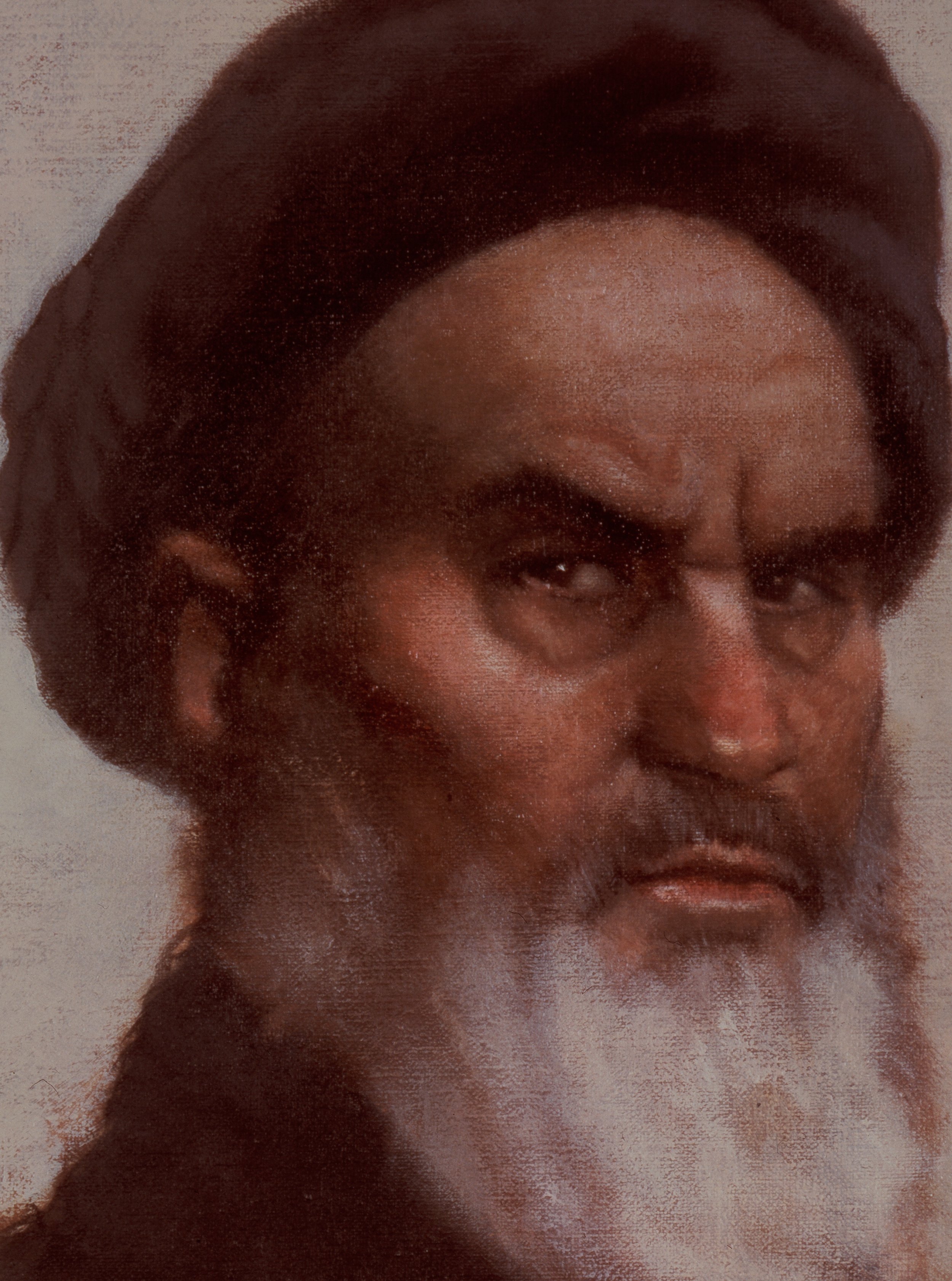

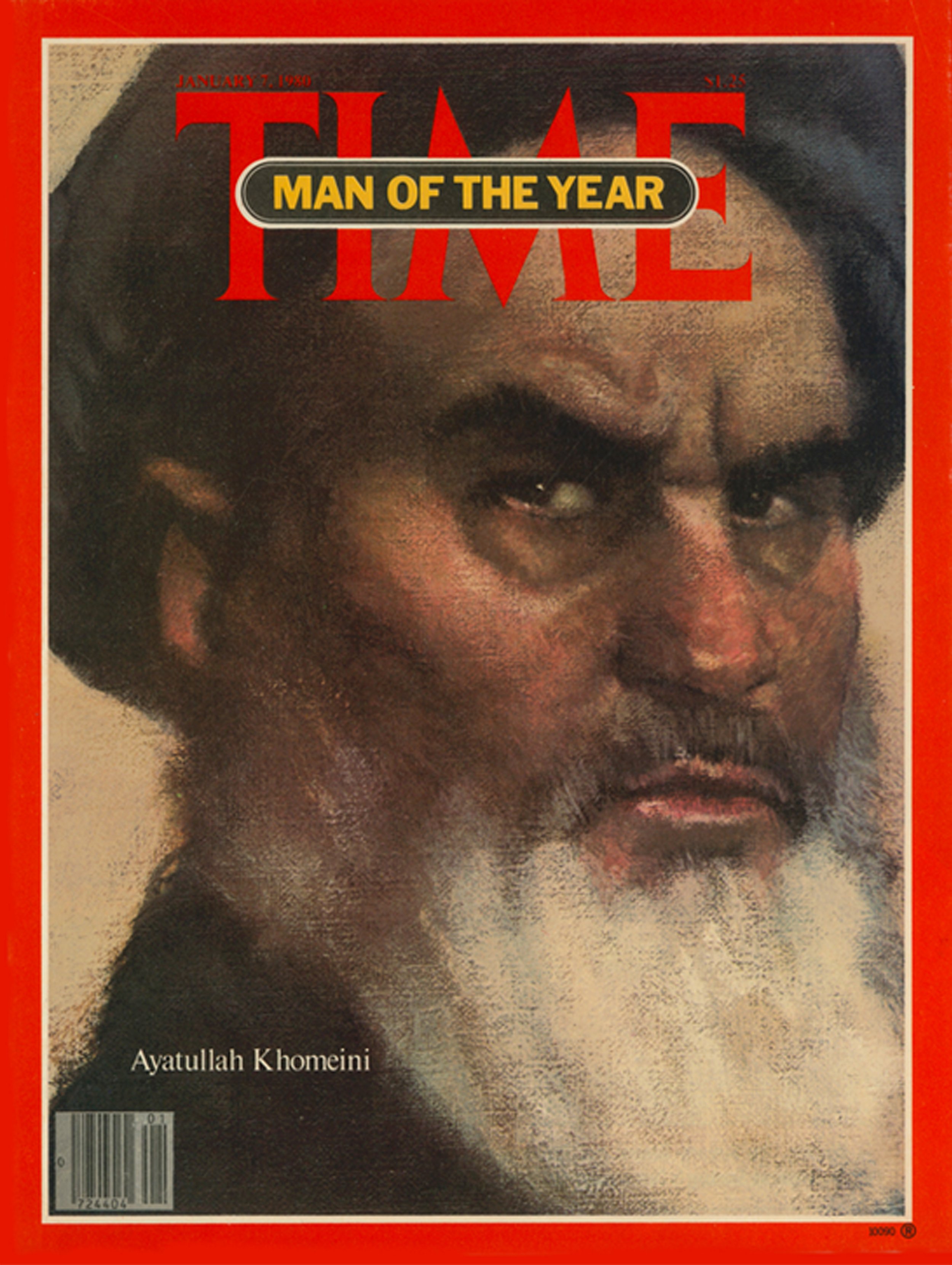

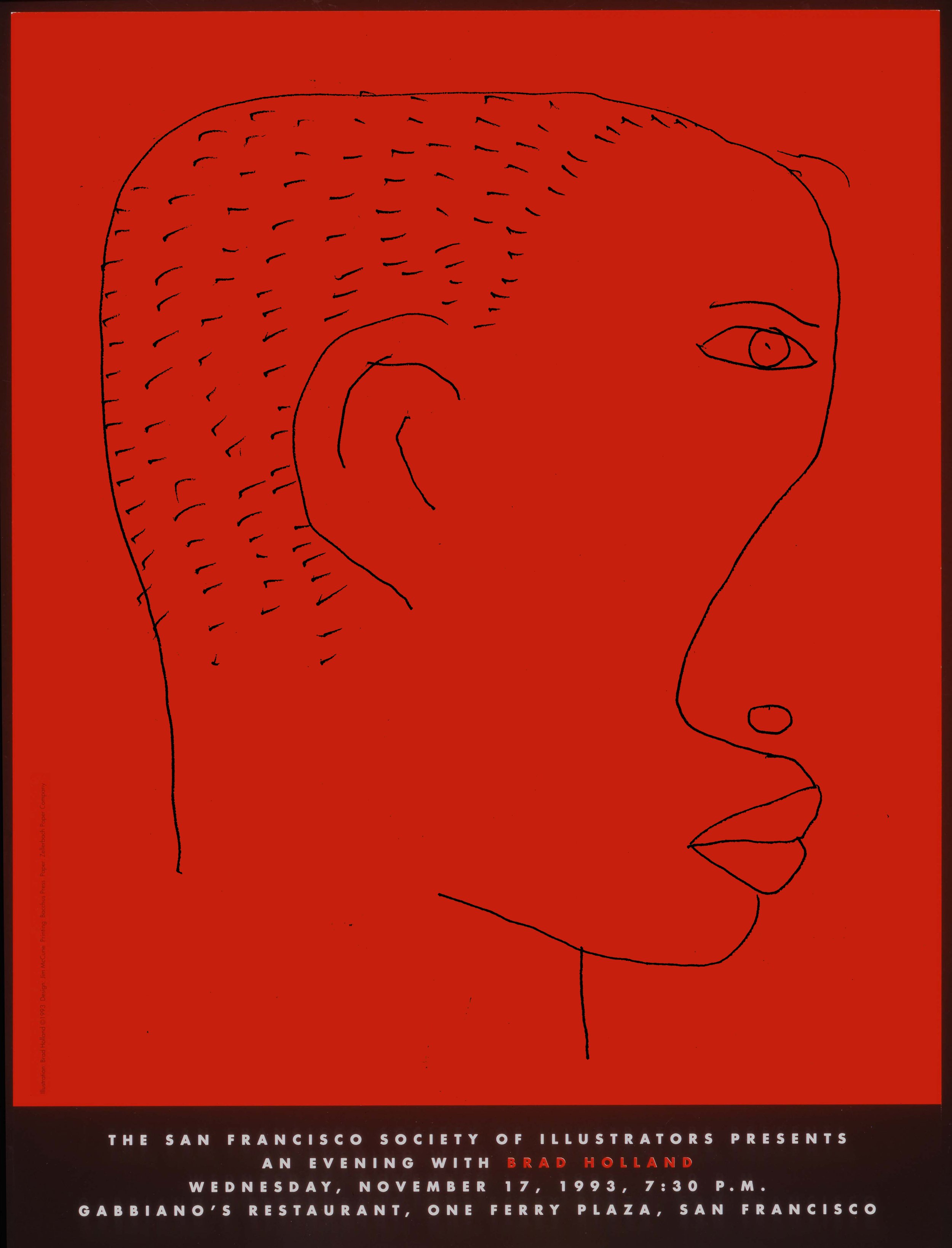

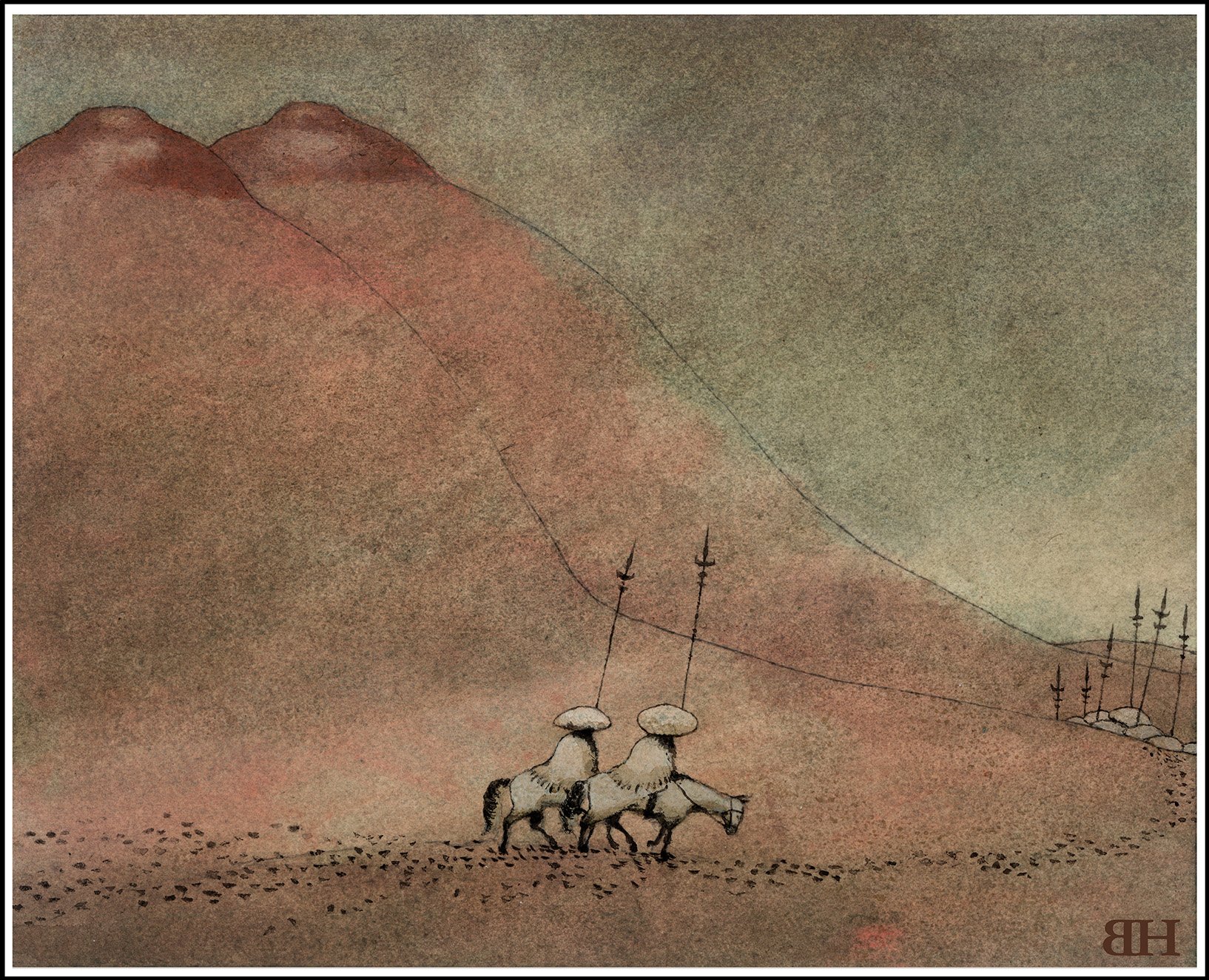

Holland’s 1979 cover for Time’s Man of the Year issue featuring Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini: The original, Holland’s crop, and the final printed cover.

Steven Heller: And pretty soon after that, other people started doing your work as well.

Brad Holland: I couldn’t do anything about that. Could I?

Steven Heller: No, but it did mark a shift in the overall style and concept.

Brad Holland: Well, it worked against me at Time magazine. For example, one guy came along who was very good. And again, he came doing somebody else’s work and then started doing mine and going around to all my clients. And he had heard stories about how artists, you know, some art directors had a hard time working with me, and he kind of promised tha he’d be easy to work with. So I remember I kind of got booted out of Time after doing a whole bunch of covers for them.

Steven Heller: Was the Ayatollah the first cover you did?

Brad Holland: The Ayatollah was, yeah, the first cover that I did for them. That was an odd case too, because they asked me to do a picture of the Ayatollah, and I didn’t like working from photographs but they gave me a whole bunch of press photographs and I found one of them that was a three-quarter view and had the features of his face, but it was shot with a flash. So it had that back-shadow that flashes always have. So I modeled my own face—because I looked enough like the Ayatollah, I thought—I modeled my own face in three-quarter view and had my wife at the time take a photograph of me.

So I used the lighting from my face and the structure from the Ayatollah, his face, but they had asked me to leave a lot of space above the turbin. Just leave a lot of space for all the type that they wanted to add. So I did this painting. It was about, maybe 18 by 24. I took it up and they loved it and they photographed it and they did a cover based on the dummy. I said I wanted to make a few changes on it. I took it back to work on it and I just, I didn’t like it. There was something—it just looked wrong to me.

They gave you a cover in those days. It was a celluloid cover with a Time logo on it. The Time logo is fantastic. It makes anything look good when you put it on with that red board or the red and white border and the Time logo, unlike the Newsweek logo, which would make even a good picture look bad, Newsweek had that clumsy drop-shadow, lowercase type that ran about one third down the way of the cover. You could hardly do a picture and cram it in under the Newsweek logo. The Time logo made everything look fantastic. So they gave you this transparent logo—it was life-size and you could drop it on anything. And I just happened to drop the thing on my Ayatollah picture. And I thought, my God, if, it weren’t for all this space around it, this would be a fantastic cover.

So I take some white sheets of paper and I began blocking out everything on my painting until I had the thing right down to the size of the celluloid sheet with the logo on it. I thought, “That looks fantastic. I’m going to try to persuade them to do it.

I thought no, they’ve already shot the thing and they’ve already done a dummy with the whole thing. It’s already probably been okayed by the editors, and once it’s been okayed no one’s ever going to raise the issue ever again. The only way to do this is to cut the damn picture out of the canvas. So I took a matte knife and I cut the thing out of the canvas until it was literally 8 inches by 10. Gone is the 18-by-24 canvas. I send up a little painting, 8 inches by 10, and they freaked out. What are they going to do?

Well, they had already covered themselves. They, you know, it was a Man of the Year cover. They had already covered themselves. They had four other artists doing covers. One person was doing a very radical cover. One was doing a Persian miniature. There was, I think somebody else doing one, and then then there was mine. So I figured, well, they’re covered. If I’ve ruined this one, I’ve just ruined it for me. They’ll get one of the other guys to do the cover anyway. So I sent it up, and it worked out perfectly. It was exactly the way the cover should have run—all that extra space was ruining the dynamic of the cover. So after that, they asked me to do all kinds of other covers. I must’ve done 10 after that. I don’t think any of them ever ran. They kept them in the morgue in case—there were all these Russian premiers, all of whom were elderly. I think Brezhnev was on his last legs, and they knew that Andropov and Chernenko were after him, and

And they were equally old, at any moment the premiership could change. So I ended up doing all the contenders for the Russian premiership, some of them were very nice. And then I did [Zbigniew] Brzezinski for Time. I think it was one of the best covers I ever did. It never ran. I’ve got it on my website. I think it was one of the best portraits I ever did, but it didn’t run.

“Well if the internet isn’t the end of Western civilization, what has to happen is we need the kind of people art directing the internet like [Steven Heller], [JC] Suares, Art Paul, Dugald Sturmer, and Richard Gangel. We need people with that kind of clout working for internet publications. ”

“I did [Zbigniew] Brzezinski for Time. I think it was one of the best portraits I ever did. But it never ran.”

Steven Heller: What did you want to accomplish by sticking with illustration? Was there something you needed to say that could only be said through mass media?

Brad Holland: Well, Reagan changed tax policy and created a bunch of tax shelters that fine artists agents wanted to take advantage of. And I got offered a couple of deals. This was back in the eighties. The deal was that you would do all the work for a fine art lithograph, and you would be paid a fairly decent sum of money by some investor. The work would never be published. This was kind of like a scene out of The Producers or something. The idea was they were creating something that they would make a down payment on. The down payment would be the payment to the artists, but then they would write the work off as a loss, and they would get a huge tax writeoff for it.

So the idea was that we were supposed to be doing fine art lithographs, but the deal was they would never be used. We would just be paid for doing the work. And I thought, well, hell, I could get a job as a caterer. You know, I might as well—if I’m going to get a tax-shelter job I might as well do something like that.

So I turned those jobs down.

But I was married at that point, and I wanted to buy a big house for my wife, so I started doing a lot of advertising and I already had the reputation for doing my own ideas. I got pretty much the kind of license that I wanted doing advertising as well.

Part of my strategy early on was simply to give an art director a lot of choices because I knew the old cliche, you give an art director three choices and they’ll pick the worst one. But I just decided, you know, I was fairly clever. So I would come up with a lot of ideas on the theory that I liked all of them and I’ve sent them several ideas so that if they picked one, it was at least one that I wanted to do. It might not be the one that I most wanted to do, but it would be one that I wanted to do. So I was happy with that. I’d save all the ideas and use them elsewhere for other things.

Nothing else I’d do for myself. So I’ve pretty much done what I wanted with my career so far. New things happen every day. I’m still—at the moment I’ve got about 15 ink drawings that I’m working on. And I’ll find a place for most of them I think somewhere down the line.

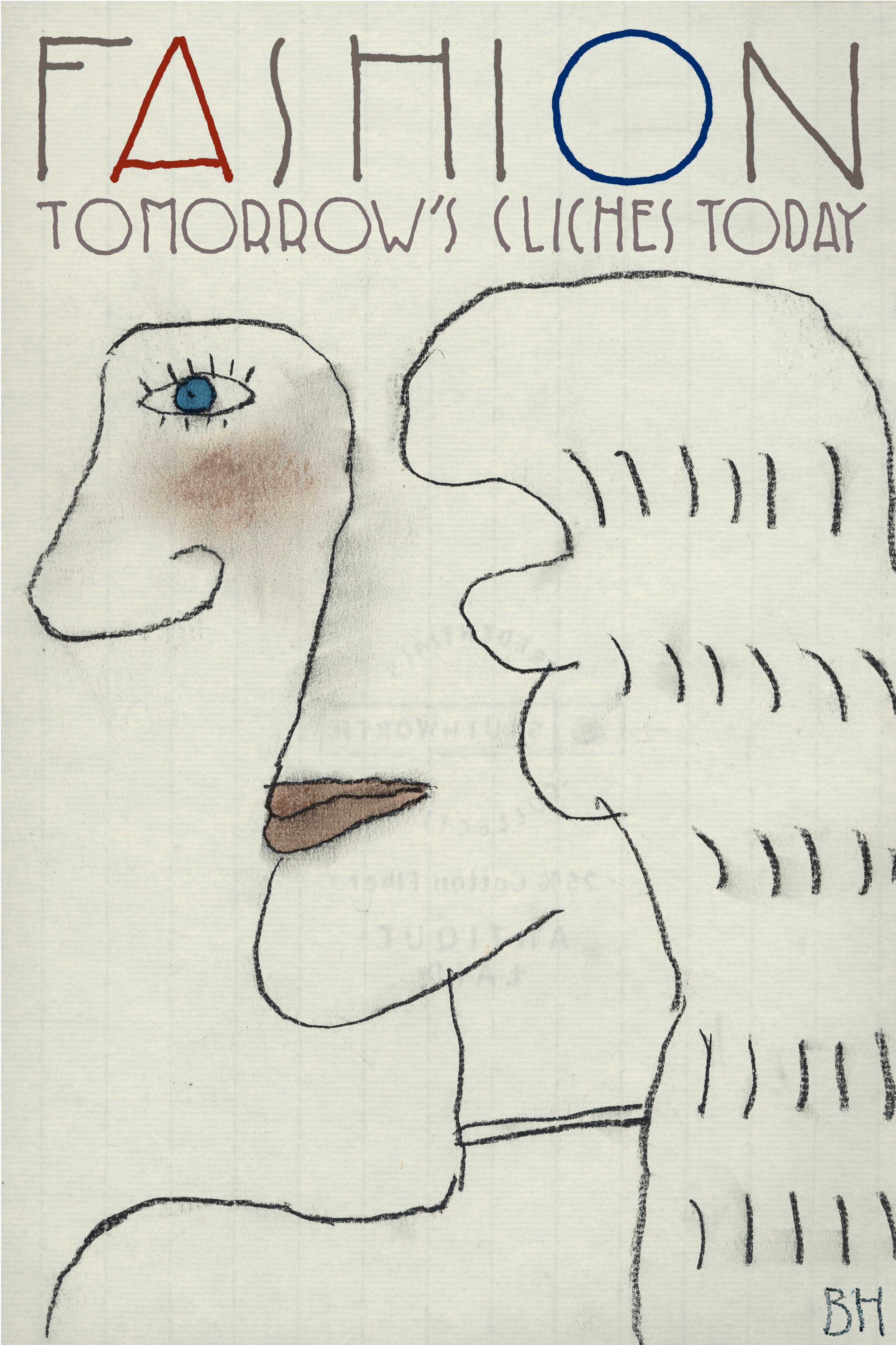

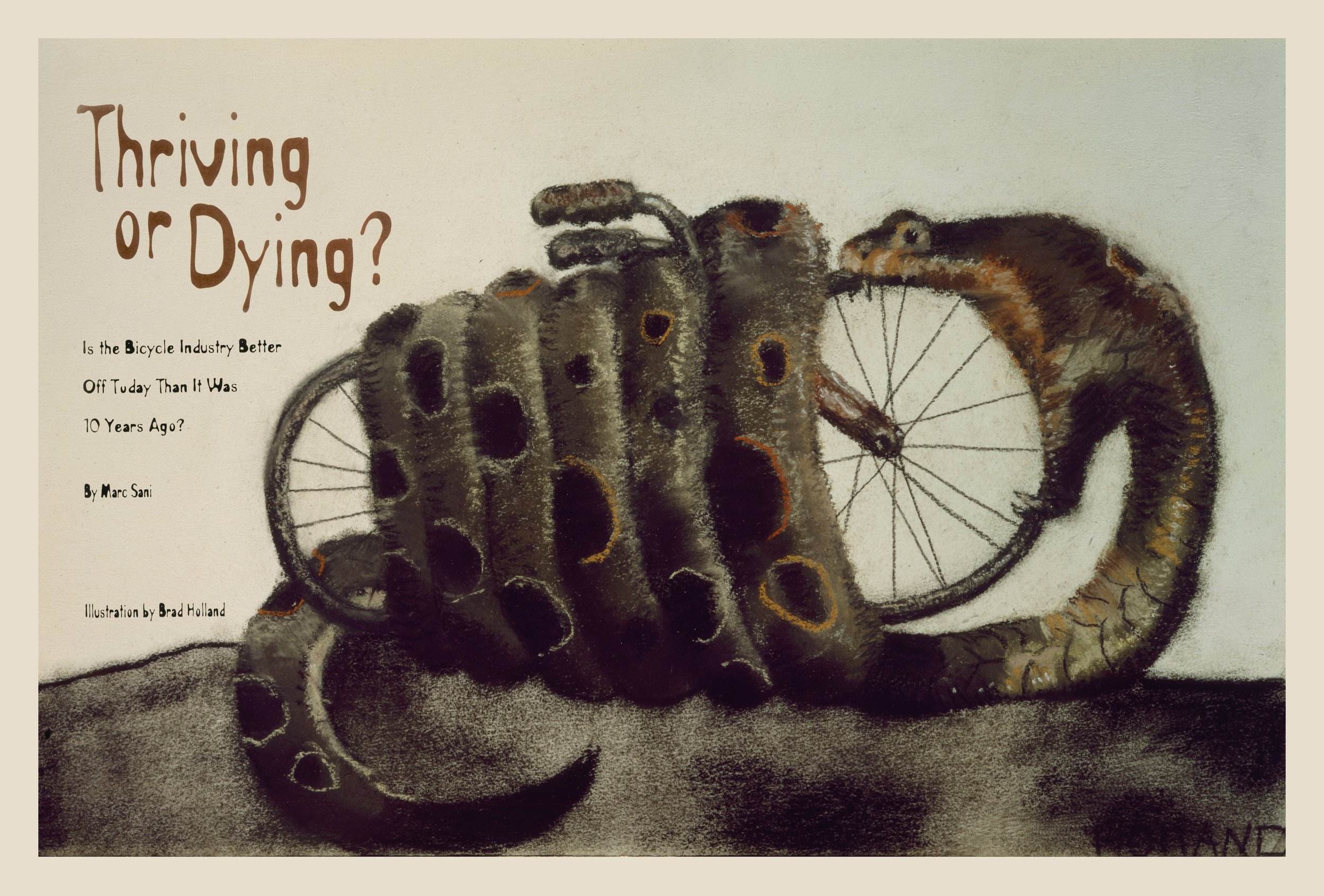

Some of Holland’s more recent work.

Steven Heller: There was a point where you moved from doing representational work that was somewhat expressionistic-impressionistic to “stick figures.”

Brad Holland: Oh come on. I wasn’t doing stick figures.

Steven Heller: You were doing primitive.

Brad Holland: What happened was I developed a bunch of ideas for sketches that I would turn into paintings, but the paintings looked overdone when I got done with them. They just looked like, well, this thing should have been left in the sketch stage. A friend, Roland Scotoni—a wonderful art director in Zurich who I had gotten to know—Roland had cooked up a deal with a publisher in a little town called Feldmeilen in Switzerland, just north of Zurich. And at the time I was thinking about quitting illustration. I had this friend, Gaillard Sartain, who’s an actor and had set out to become an illustrator.

Gaillard came to New York and did a few illustrations and then went back to Tulsa and became a local TV star, and then got into Hee Haw and got into the movie Nashville and then went out to Hollywood and he played lots of parts in lots of movies. He was in Mississippi Burning and Fried Green Tomatoes. He’s made quite a good career as an actor. He was filming Hee Haw one year, and I went out just to hang out with him. He wanted to show his work to Playboy. And so he and I were going to go to Playboy together and I was going to introduce him to everybody and take him around. By this time he was a big local star in Tulsa and in all the localities—Iowa, Texas, Arkansas—he had a weekly show, Friday, Saturday nights, whatever, called the Uncanny Film Festival. It was one of those things where he showed old monster movies and did a lot of schtick with Gary Busey, who was a guy who had gone to college with.

Gary was still using the name Teddy Jack Eddy in those days. And so, Gaillard and Teddy Jack Eddy were the stars of this local TV show. And then Gaillard went national when he got into Hee Haw. So I went out to hang out with him and at Hee Haw one week. I spent the week in Nashville with all those characters. And then Keith Carradine came by—they were shooting a scene at the Nashville airport for that movie Nashville. It was the assassination scene. And he said, “You guys want to be in the movie, come on by.”

Well, I was scheduled head out to Playboy and Gaillard was supposed to come with me, but he decided he was going to try to get into the movie.

So he hung out, and he and Carradine improvised a scene at the cafeteria that day. And it made it into the movie that was Gaillard’s entry into the movie business. At any event when I had gone out to California with Gaillard that summer, and I was trying to talk to all these screenwriters just about, because I was getting imitated—there were so many people imitating me beat that point. I thought, well, maybe the thing to do is get out of this business and get into screenwriting. Anyway I had wanted to write plays when I was younger. I had lots of ideas for movies. So we went out there and I met quite a few screenwriters, talked with them and I was just thinking of changing my name to Christian Bradford and starting in as a screenwriter.

But I came back and I had this, there was a letter waiting for me from Switzerland, from Roland Scotoni, if you forgot where the story started, and Roland had invited me to Switzerland for a month, all expenses paid, to just do lithographs at this company called Vontobel. They had used to make great big lithographs on these giant stone lithograph plates. So I went over there and I spent a month doing lithographs. And I began keeping a sketchbook. Nick Megalon, who used to be the editor at a Mad magazine. had done an article about me for American Artist magazine, and Nick was a great pen and ink artist. So he gave me some sketchbooks that he had bought and was afraid to use because the paper was too big.

And while I was over there, I started keeping sketchbooks. And when I came back, I got this offer. I’d done all these lithographs, but I had just been thinking about all these sketches that I had been doing. And when some jobs came up, I would do sketches and then turn them into paintings.

And then I would look at my work and I thought, well, the sketches look better. Roland called me then, and he wanted me to do the Swiss art directors club yearbook. He wanted me to do a painting for the cover And then all the inside pages would be the sketches that I did. And I said, I got a better idea. ”Why don’t I do the cover and all the inside pages fresh from, just from scratch. I’ve got all these ideas that I’ve done his paintings, and I think would look better as sketches.” So that was the way that started. I did 40 drawings for him, and we just applied them to this Swiss art director sketchbook, and it got a gold medal from the art directors club in New York.

And the Swiss art directors club would have given it a gold medal, except since they were the client, it wasn’t eligible. They gave me a silver medal. But that got the attention of some art directors who called, so all of a sudden I just began to get calls to do more work like that.

Steven Heller: What’s work like now magazines have gone digital?

Brad Holland: Well, we’ve been hearing about “print is dead” ever since David Carson began doing Ray Gun.

Steven Heller: So this show is Print is Dead. Is print dead?

Brad Holland: No. Now with the internet, well if the internet isn’t the end of Western civilization, which I do have a bet on, what has to happen is we need, the kind of people, art directing the internet that you and Suares and Art Paul and Dugald Sturmer and Richard Gangel. There were five art directors who really made a big difference back in the 1960s. And you were certainly one of them. We need people with that kind of clout working for internet publications.

Internet publications still have to work through the firewall issue.

Magazines need to find some way to get subscribers, and then they need to get through the technical problems. I did some work for a corporation and we went through all the spaces: that if I do the picture, this size, it’ll run in this format, on this device and this format on that device. So there’s still some technical problems that have to be solved with internet graphics, but we need the kind of independence on the internet that we were able to find in magazines.

We need to keep the tech companies from doing away with copyright. As you know, I got very involved in all this nonsense 20 years ago, much to my chagrin because I never wanted to be part of this. I ended up testifying before Congress, both the house and Senate, and we ended up fighting. We stopped the bill from passing, but the so-called “orphan-works” bill would have orphaned every work on the internet, not just from artists, but from ordinary people.

You know, if you put a picture on a Facebook page, that would have been an orphan, unless you had registered it, picture by picture by picture by picture. You would have had to have filled out a form and registered it with a commercial registry. They were introducing a law that would have allowed a so-called derivative work to be made out of any picture they took off the internet. So you could put a picture on a church social networking site or an internet site, some kind of Facebook page, and these internet spiders could harvest that work, declare it an orphan, plop an O on it.—it looked like a copyright symbol with an O on it.

And it would have been fair use for anyone to use. Stock companies could have taken those pictures, made slight changes called derivative works, which would have been legal, then copyright at that work in their own name, and then had machines crawl the internet to sue anybody who used one of their pictures.

You could have been technically sued, presumably for using your own picture if you had used a version of it that they had doctored in the internet,

Steven Heller: The internet has provided a lot of problems for creative people and non-creative people. I mean, the internet is an open pit of danger.

Brad Holland: Yes it is. And companies like Google are trying to make it more dangerous. They want it to open everything. The internet now allows you to take any of my pictures off the internet and use them for private usage. You know, you can’t do anything about that. And I wouldn’t want to, but this law, actually, the Senate passed a 20-page bill that we got down, It was going to open usage to all, all usage, any commercial usage, we got it rewritten to be for non-commercial uses. Then we heard that they had made one change. They only made one change to the bill, and they were going to vote on it. Well, they wouldn’t tell us what the one change was. So we had to look through the 20-page bill and sure enough, they had changed the word “non-commercial” to “commercial.” That one change to the bill would have opened everybody’s work workup for commercial usage, which meant that anything on the internet could have been used anybody for commercial purposes.

Steven Heller: What is the satisfaction or joy that you get from being an illustrator, from being an artist?

Brad Holland: I’m doing the same thing I did when I was five years old. Really. When I was five, I used to listen to the radio. We didn’t have a TV in those days, TV didn’t come until I was six. So I was doing comic strips. When I was four or five years old, like I loved L’il Abner. That was my favorite comic strip.

I wanted to do things like draw Lower Slobbovia and create characters like the Shmoo. I was a big L’il Abner fan and so I was doing comic scripts until I decided I wanted to do Walt Disney movies. and then I wanted to go to Disney, except that when I started thinking about Disney, I didn’t know what to do. I knew I wanted to write the stories, I wanted to animate the scenes, and I wanted to paint the backgrounds. Ha! Fat chance I would have ever done that at Disney. Once I got to Chicago and saw the Art Institute and began to see real art, my attitude about that changed. And since then, all I’ve wanted to do was do what I did when I was five, with the values that I’ve picked up along the way.

And I’m still doing it: I’m a mature five-year-old is what I am. I’ve gotten away with it all this time. Imagine that.