String Theory

A conversation with Racquet editor-in-chief and cofounder, Caitlin Thompson

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT LANE PRESS

Media, and most every brand in general, talks a lot about building and nurturing a community. Tribes, even. Finding one, inserting yourself into it, and then making your message an integral part of it. And what activity creates a more loyal community, than sports? If there is the ultimate niche audience, sports is it. It goes without saying that every sport has fans. And some lend themselves to something beyond fandom; they are lifestyles.

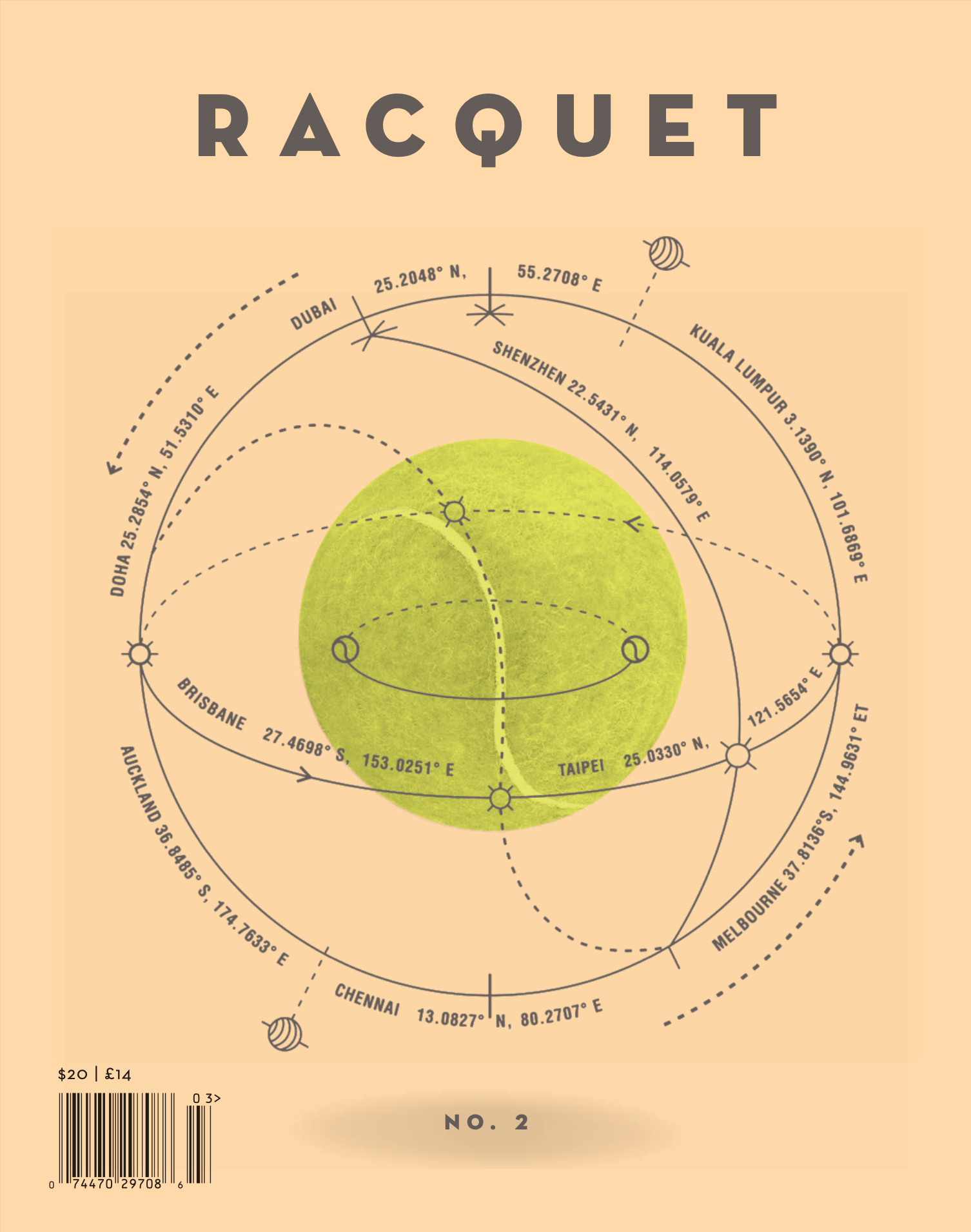

And few magazines have built up a brand around a single sport and its audience and their lifestyle as much as Racquet.

Launched with a Kickstarter campaign in 2016 by Caitlin Thompson, Racquet is a presence at major tennis events and has inserted itself into the lifestyle of tennis fans and players alike. The path has been rocky at times, but Thompson is clear about her aim to provide a “premium experience at a premium price,” as she told the Nieman Lab in an interview in 2017.

Like any other media, Racquet will live and die based on a business plan, and it is quite possible that Racquet magazine is just a small part of a larger creative media agency, all centered around a global community. And while she is not loath to smash some volleys in the direction of the tennis establishment, she is doing this while also trying to recenter the entire community and become its new beating heart.

Caitlin Thompson has much in common with the world’s top tennis players: passion, drive, ambition—and a willingness to make … a racket.

Arjun Basu: Caitlin, you were a tennis player.

Caitlin Thompson: Yes.

Arjun Basu: And you went to school on a tennis scholarship, right?

Caitlin Thompson: That’s right.

Arjun Basu: And then you got into journalism and a lot of political journalism. And then you had this Kickstarter. So how did you get to that moment? What was your journey to that moment? What niche were you filling? What was missing in your consumption of media that you saw an opportunity for something like Racquet?

Caitlin Thompson: Tennis was something I grew up with. And for me, my connection to the game came through my grandmother. It was a way to connect with another person. Probably the person I loved the most in my world.

My parents were classical musicians. They were itinerant. They would go on tour for extended periods every summer with the symphony. At the time it was the Montréal Symphony when I was working growing up. Later, it was the Atlanta Symphony and they would be on tour for a couple of weeks at a time, in Asia, Europe, wherever.

And when I was really young, I started basically getting shipped off to go stay with my grandmother who had taken up the sport of tennis as a retiree. She was a nurse who had done a lot of sort of blue collar jobs. Not from a lot of money, but she’d taken up recreational tennis in the tennis boom of the seventies and eighties. And on public tennis courts, she had taught herself how to play and it became her whole world.

And for me to get sent to her house in Phoenix, Arizona meant that I was part of her world, which meant that I was going to play tennis with her every morning, whether I knew how to play or not. And she would fill up a giant jug of Arizona tap water, bring her Marlboro 100s, and go out at 5 am, as people in their 60s and 70s do, and just play tennis balls. I can picture that scene. It was incredible—chain link fence, bringing our own hopper, balls that would get dusty. And just, this was like my magical time with this lady who is so funny and cool. And she wasn’t the world’s greatest tennis player.

She didn’t have the world’s greatest game. We didn’t even keep score. And a lot of people—growing up as I did in the competitive tennis space later on I started competing in tennis and got to be pretty good at it—but their origins and their dreams were always tied to professional glory and winning Wimbledon and being ranked number one, this or that.

And for me, that stuff was interesting enough, but really the goal was always just to recapture this joy that I had as a little kid playing a game with my grandma. And so after competing in the sport up through college, which paid for my college. It’s not entirely clear to me that I would have been able to afford to go to any college I wanted to, so this was certainly a very big windfall for me personally to have college paid for, especially one that offered a degree in something that I knew I wanted to study.

The Missouri School of Journalism was on my radar and I wasn’t good enough to get recruited by everybody; schools weren’t falling over themselves to have me play on their tennis teams. So I tried to make a pragmatic choice to say I’ve already had one career that has done me well, and I’ve probably summited, or at least gotten to my ceiling.

But now, knowing that I had excelled in English and yearbook classes—I even started a newspaper on my block when I was 11 years old, reporting on my neighbors. I think the news bug and the storytelling bug was in me very early.

Arjun Basu: Wait a second! Reporting on your neighbors?

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah. I got into some trouble as well because one of my neighbors was an amateur arsonist and I wrote about it and his parents were not thrilled.

And that’s also when I learned about libel laws. So, an education at an early age. I didn’t do too many editions of the paper. I don’t think the neighbors really loved it, but I would go door to door selling it for a quarter. I knew I wanted to tell stories and I grew up reading the Esquire of David Granger’s era and loving long form journalism, loving storytelling, loving the idea that magazines could really set an agenda, and wanting to set an agenda.

And I studied magazine journalism at the University of Missouri, I got to work on the, I don’t want to call it a student magazine, because at Missouri—the Missouri method, as they call it, is that if you’re a broadcast student, you work at the local NBC affiliate; if you’re a newspaper, you work at the local newspaper that is in competition with the other media outlets; if you’re working in the magazine sequence, you work for either the alternative weekly or the magazine that covers international affairs. And I did both because—and it’s not like you’re working for the college newspaper or the college magazine. They have those too.

But the journalism students were really encouraged and mandated to work for publications that had a real life audience of adults and it’s you know, it’s immersion really, and it was an immersive education. That was great. However, one of the things that was not great about that education is that immediately upon graduating, the internet had begun decimating a lot of magazines and newspapers, whether or not those magazines or newspapers were aware of it yet, and newsrooms even at that time in the early 2000s were already… . You know, the era of the golden age of the bar cart and the expense accounts and the black cars and all that stuff was certainly ending if it hadn’t already ended.

And so for me, getting into digital media was the only real option if I wanted to have a job that paid me; I couldn’t afford being an editorial assistant for $14,000. I don’t come from a family with a trust fund, but also getting real experience to be able to do stuff in the digital space was just pragmatically where I could report.

And so I worked overseas for a little bit. I worked in China for a magazine for about 18 months. And then I came back to the States and worked at the Washington Post. And at the NewsHour, which is a program on PBS, still somehow going, still somehow a program on PBS, it felt dated and dusty even at the time.

And then I got hired to come work at Time magazine up in New York, but all in the sort of niche of political reporting. Somehow I just fell into politics as my default subject matter of expertise. And I didn’t love it. I wasn’t a political, economies major or anything like that. It just seemed like that was where important stories could be told.

But I had, after my third presidential election, somewhat of a realization that we are covering politics like sports. But what I really want to do is talk about politics for their own sake, how to make the world better, issues, things that matter to people, not who’s winning the news cycle. I found that very cynical. I found it very pointless. And I think we’re seeing what the effects of two decades really of that style of coverage has wrought us, which is, you turn politics into entertainment, you get entertainers.

And I thought actually conversely, in some weird way, going into sports would allow me personally to talk about or commission writers or reporters or illustrators or whoever to grapple with issues that I care deeply about but in the guise of something that’s fun and global and interesting which is this sport that I grew up loving that was actually on the right side of history and ahead of its time and bringing together a lot of disparate conversations and reaching a lot of far flung places and it was handbuilt because nobody else was doing anything like it in the space. And so that’s a long-winded way of saying all of this felt like it organically led one to the next.

Arjun Basu: Obviously you never lost your love of the game and you were still playing. Was there any media that you were consuming at the time about tennis? Where did you go for stories or what were you reading?

Caitlin Thompson: It’s a good question. And it assumes that I didn’t lose my love of the game. I in fact did lose my love for the game for a couple of years. My last match at the Big 12 conference championships was—I did not finish. My team lost before my match had a chance to complete. And I remember leaving my rackets, my bags and my shoes.

And keep in mind, this is before the climactic scene of Ritchie, “The Baumer,” Tenenbaum, in The Royal Tenenbaums. I was like, I really did that. I just was done. And I didn’t pick up the racket again for many years because I was completely over it and treating tennis like a job. But obviously I still followed the sport and I still cared about some of the storylines and it was weird because a lot of the sport changed in my time as a competitor and as a young professional.

And it atrophied, the conversation around tennis. That began for me with this public tennis court, tennis in culture, in movies as a symbol. I grew up watching Trading Places and Who’s Harry Crumb?, and famous Italian Fellini films where tennis was just kind of part of it.

It was just as much about drinking your water out of a tennis ball can as it was a country club, which I had never belonged to. And the tennis space, even though the nineties and early two thousands gave us some amazing athletes, obviously Agassi, Chang, Becker, Courier, Sampras, the Williams sisters towards the end of the nineties, Capriati, et cetera.

Arjun Basu: Steffi Graf.

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah. Steffi Graf. I had a poster of her on my wall.

“I grew up reading Esquire and loving long-form journalism, storytelling, and the idea that magazines could really set an agenda.”

Arjun Basu: Never would I have thought in those days that Steffi Graf and Andre Agassi would be, not just get married, but would be a very successful couple. But anyway that’s not what we’re here to talk about.

Caitlin Thompson: We could have a whole separate discussion about our speculation about the marriage of Steffi Graf and Andre Agassi because I agree with you. Never, listen, you don’t know, it takes all kinds, everybody’s got their person, but yeah, like I really saw that despite the fact that tennis was really producing a lot of very interesting stars the world around tennis kind of shrunk to only be about those stars.

Tennis stopped being this societally interesting vehicle for social change. It stopped being this place that it didn’t take a private club membership or a ton of money to access, When people talk about tennis being a country club sport, like that’s so unfamiliar to me that I am forced to reckon with the fact that’s how a lot of the sport was perceived during a lot of my lifetime.

And that was never my reality. And these sorts of examples kept cropping up in the tennis infrastructure. The tennis world has shrunk the pie, but the people getting a slice of that pie, the Nikes and the IMGs, and a few of the Grand Slams have gotten so rich off of it. They’re not incentivized to actually really grow the sport or make it bigger.

And that was true up until a couple of years ago. Even after Racquet had launched and we were in the market really during the pandemic, did the public kind of rediscover recreational tennis and fall in love with it and realize like, “Oh, hey, actually it’s not that expensive. It’s not that hard. It’s not that inaccessible. It’s quite fun. And you can play it whether you’re nine or 90. Hey, this is maybe something that we should re explore!” And then obviously tennis has its sort of second boom.

So I was not reading a ton of stuff. I would occasionally see something in Grantland, obviously, famously growing up on David Granger’s Esquire, reading David Foster Wallace, reading, occasionally, one of the greats like Sally Jenkins would take on a topic or an issue, Mary Carrillo was bringing tennis to a mainstream through commentary at NBC and Olympics. But it was really few and far between. And it wasn’t until I had a lightning bolt moment.

Reading a Neiman Lab article about Tyler Brulé, my fellow Canadian, who had gone overseas and started a period of pretty cool and mysterious reinvention as a Gatsby kind of character, that I realized: “Oh, there’s a model actually for this and what he’s doing with Monocle, where he doesn’t care about mass, he cares about class, and affinity, and depth, and engagement, and this guy would just as soon have you go to a Monocle conference in Gstaad, or buy an £800 Japanese umbrella that was curated for that shop on Chiltern Street, as he would have you be a subscriber.

But guess what? That’s probably the same person and those people are going to be loyal forever and their price and willingness to be in our Monocle world is infinite. That’s when I realized: Oh, there’s an actual model to this. Because the mainstream tennis conversation had just been so shunted aside without occasional flares of interest or storyline, that just felt there was this white space, this whole bunch of white space, but coming from Time magazine where, you know, our, audience somehow kept growing, but our revenue somehow kept shrinking, and Facebook and these platforms started eating our audience before I think a lot of the executives knew what to do.

I would argue they still haven’t figured it out. If you had one eye open, you could see: Oh, this is all going to go into niche media. This is obviously how things are going to play out. So I think, obviously, there’s this deep passion that’s driving me that felt like tennis deserved a better story.

Tennis has not done a good job telling its own story. And that goes from long form journalism and photography and illustration, obviously, but also marketing materials and events and outfits like it’s just oh, man, we got stuck somehow in like 1993. What happened? And so the mission of Racquet was always this bigger idea.

And I think once I stumbled on the container, which Tyler Brulé designed for me, for us, and I saw other people attempting it—oh, here’s Kinfolk, doing that same thing; oh, here’s Lucky Peach doing it, but in food, with a bit of an edge. Oh, here’s Rapha, who’s figured out how to monetize a cycling community, a sport I don’t care about, I don’t think it’s particularly interesting to read about, but guess what, they do, and they’re speaking to their incredibly engaged audience who is going to join a membership club that is virtual and show up for a ride on the Great Wall of China. Like, all of a sudden the model started punching me in the face.

And that’s when I figured out, okay, filling the container is always an exciting and fun challenge, but anybody who’s spent time in the media and newsrooms, who’s had even one business meeting knows that’s the fun part. The hard part is how do you pay for it? The challenge is how do you pay for it?

Because guess what? Coming up with incredible ideas and journalism and writers willing to do stuff, like, that’s gravy. The hard part is how do you get it paid for? And I think that’s really the revelation that allowed Racquet to come into being. And, obviously it’s a formula we’re still tinkering with.

We’re still constantly looking around the corner and being like, okay, are we positioned well for what’s next? But at the same time, like at the very least seeing the possibility of niche media to connect and have a flourishing ecosystem. If you take enough care to build the brand such that it can be wrapped around this ecosystem was always a huge part of the DNA.

Arjun Basu: So Monocle, as a, as an inspiration. Monocle is obviously more than the magazine. It’s an agency. There’s a little store. I used to work for an agency and the office was right around the corner from one of the Monocle shops in Marylebone. And yeah, when I saw that, that’s when it all started making sense for me in terms of their ecosystem. And then Winkreative. And then they went into design and industrial design and all sorts of things. And so your ecosystem above and beyond the magazine, which is the obvious one.

Caitlin Thompson: The magazine is, in a lot of ways, the smallest part of the ecosystem. It’s the part that aficionados and readers and true believers are connected to, but in a lot of ways it’s built to be the loss leader, because…

Arjun Basu: Yeah, you’ve said that before in an interview, that journalism is really a loss leader for the other things. Meaning it’s a pure brand, it’s the extension of your brand, more than anything.

Caitlin Thompson: Completely right. And don’t get me wrong: The journalism has to be excellent. It has to be top notch. Not only because of anything I would want to put my name to it, but also just because there are many incredible writers, journalists, investigative reporters who can and want to find rich subject matter in this in and around the sport, so that I want to make it sound like that’s not easy but it’s straightforward.

What’s difficult, and I think what I’m more proud of, is not that we have a cool magazine. A lot of people have cool magazines. A lot of people pay for those magazines themselves. A lot of those magazines are vanity projects A lot of those magazines are brand projects like Sandwich magazine: Cool magazine, incredible photography, who knew?

I did, but not everybody knows that it’s a brand play for Sir Kensington’s, which is owned by Unilever. So Unilever is taking a little flyer on a print publication that almost nobody’s ever going to know they have anything to do with, just so they can promote sandwiches. Just so this condiment line can become more robust of a return to shareholders.

“Tennis has not done a good job telling its own story.”

Arjun Basu: And that’s to me, that’s one of the purest magazines you can have. The agenda doesn’t matter almost, because they’re just creating a magazine about sandwiches. And, look, American Express did it, right? They did it and they do it now. And whenever you tell them that Travel + Leisure is an American Express product, they’re like, what? Yeah. Just look at the masthead. It’s right there. They’re not hiding it.

Caitlin Thompson: No. And I think the thing that I learned in journalism school was that mattered, and that was not right, because it doesn’t matter.

Arjun Basu: Church and state.

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah, and I think, that’s not to say that you can’t, you have to, you shouldn’t disclose conflicts of interest. That’s not to say that, you have to, you have to make compromised decisions. But I think it's naivete only if you’re exorbitantly rich and are funding an art project. A lot of times I think about growing up in Canada and then moving to the States and had certain things gone differently, Racquet could be like a Canadian Arts Council funded art project, which, like, maybe that’s not a bad thing. You watch Sarah Polley’s movies and they’re great and fantastic. Amazing art can be done by writing non-profit checks.

That said, one of the things that was very clear early on, especially because I think, part of being entrepreneurial is a little bit of naivete generally, where you’re like: we didn’t do this because it’s easy, we did it because we thought it would be easy. Like you think: Oh obviously we’re going to make something amazing with incredible writers.

And, I hand recruited Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Sasha Frere Jones and all these amazing folks who I knew from my larger media footprint. And of course, like everyone’s just going to find out about it by word of mouth and subscribe and before we know it, we’ll have a giant circulation.

It’s when that doesn’t happen. What else is your plan? And so very early on, it was very clear, like people wanted to meet up with each other. We wanted to be out in the world as a storyteller who could not only tell stories on our own behalf, but on behalf of partners.

And obviously we’ve said more no’s than we would, we’ll ever say yeses, we do want to help promote the tournament in Singapore because Singapore is cool and people should want to go there and they should bring their tennis racket and have a hit in the morning and go to a food market and then also see the best tennis players in the world.

Yeah we’ll take on that assignment and do a cool poster and put it in the magazine. Sure. So I think there, from the early days, was always the sort of appetite for: if we’re going to be in for a penny, we’re in for a pound. If we’re going to help the tennis ecosystem, it’s not just going to be from the outside in.

It has to be both things. It has to be helping the inside reach outwards. So working with some of the folks inside the space, but also really trying to help the tennis world by getting them new fans and getting them a new audience. And I think, the fact that a bigger cultural audience happens to be much larger and a bigger addressable market means that when you are sitting down with brands or investors and say, “Hey, look, the TAM [total addressable market] for tennis is actually huge.”

They just haven’t done a good job of growing it themselves. We can help them. Then it’s a win. And I hate to make this—I hope this doesn’t sound cynical—it’s just pragmatic, right? Like in a world where the barriers to entry for publishing and self publishing are quite low, but the business models to help those things sustain are quite difficult to figure out.

If you’re willing to utilize a brand umbrella to do a couple of different things simultaneously, I think you have a greater chance of succeeding. And I’m only really interested in people who are, through a mission-driven, purpose-making, something that feels very authentic, but making it in a way that is successful.

And I view our success as our continued existence after nine years in a media landscape that’s been nothing but inhospitable. But also the fact that we are changing tennis. We are changing the conversations around it. We are holding power to account. We are calling out domestic abuse through thorough investigative reporting resulting in legal ramifications.

When we see it, we are calling on the leaders of the sport to make responsible decisions when it comes to dealing with foreign governments that are sometimes hostile to women, gay people, Washington Post journalists: as an alum, that one feels particularly sensitive to me. But also we’re going to throw massive amazing parties because tennis doesn’t have them already.

Brands are willing to pay for them. And the people who come to them want to meet each other and feel like they’re all part of a larger thing. And if we can all wrap that around a magazine issue launch, but that actually is what pays for most of the stuff, then great. Same thing.

Arjun Basu: Like a reminder to the community that the community actually exists.

Caitlin Thompson: Completely right. And what I found in negotiating one of our first brand deals, which was an in-kind deal where we would distribute the first couple issues of the magazine in-room at various Ace Hotels in exchange for giving the Ace Hotel free ads in the magazine, and they would give us essentially free events.

So a space, a DJ, some drinks, a hang. We launched our first one at the Ace Hotel in Shoreditch. In London, our second at the Ace Hotel in Palm Springs, and I didn’t really know who would turn up. I knew some of our friends would turn up and we would have some familiar faces and that’s always fun, but I didn’t know who would have heard of the magazine or seen the Instagram or interacted with any of our other content later, obviously the podcast and some of the merch and all the other stuff we do, but it was really interesting because I figured these would be like tennis diehards. They were like, “Oh, we love that one piece where you talked about Serena’s rivalry with Justine Henin.” For the most part, it was like, Oh, I’m a creative director. Tennis is so cool.

I’ve never felt like I could justify showing up at a tennis event. I never knew enough about the sport to feel like I belonged. I never felt like there was anything for me or I could see myself in it. And I think that was a very early lesson, because when people are following you and they’re just names on a spreadsheet or reporting demographically on a digital platform, unless you’re surveying them, you don’t know what their area of expertise is.

It’d be like working at Architectural Digest and assuming everyone who consumes your content as an architect. It’s “Oh, huh, these are like fans and we’re giving people an excuse to get into something.” And that was a very early, powerful realization. Especially because it was a struggle to grow the subscriber base. That was a very clear indication: Oh, this has to be part of our DNA.

And there’s a real want and need here. And so from a bigger picture standpoint, like the Racquet brand wants to be global, it wants to be film and TV. It wants to be merchandise. It wants to maybe be a tennis tournament. It wants to be translated into other languages. It certainly wants to be a bigger thing, not because my ambitions are endless and I want to do all this work but just because that’s where the, that’s what the space will bear.

And also that’s what it needs. And I haven’t been given a signal by the market or by anybody who is joining sort of the mission that’s off base. But I tell you what, like I didn’t start Racquet because I desperately wanted to be an entrepreneur. I wanted to start Racquet because I wanted to work for it.

And Tennis magazine was already dead.

Arjun Basu: So it’s an experience. You’re building an experience around tennis, essentially. And people are showing up.

Caitlin Thompson: I think a lot about what empire builders I admire are doing. I spent my entire college and most of my early career admiring journalists and my admiration is deep and unending and I read editor’s letters and I love the way, that you know, a lot of writers and editors and journalists think, and make, and do, and for a long time I’ve considered myself part of them.

Occasionally I get to commit an act of journalism here or there, and it’s really fun and great, and I’m reminded that I like it and I’m not terrible at it. But what I really think about, and I think this is maybe something that differentiated me from some of the kids in my magazine journalism classes, is It was always really interesting to me to see how people were building their universes.

I mentioned David Granger. He built a universe at Esquire. Luckily for him, it was a time that, magazines were flush with cash. Hearst had no shortage. Yeah, I think they just picked up the phone, booked the first 10 watchmakers who wanted to advertise in Esquire,

hung up the phone, and went to a long boozy lunch and called it a day. I’m pretty sure that it was not that hard to make money in media when media was one hegemony run by basically three publishing companies out of New York, right? Not to say that there wasn’t incredible, excellent journalism being committed because there was and it was at the time.

But I think those are luxuries of another day that I didn’t expect to have handed to me and certainly haven’t. And so for that reason what’s really interesting to me is okay, Anna Wintour is in Vogue China, she’s creating Vogue World. What are the ways—that even as maybe the circ increases, but the ad page CPM decreases—what are the ways in which the brand extends that this still feels like the coolest thing to be at?

“The magazine is the smallest part of the ecosystem. It’s the part that true believers are connected to, but in a lot of ways it’s built to be the loss leader.”

Tennis players will stick around after the U.S. Open is over so they can go to Vogue World. What is she doing? What’s GQ doing with its hype covers, with its sports coverage, with its parties, with its gobbling up of Pitchfork, so now presumably GQ Music? What are they doing that makes this world not only attract but retain denizens?

That’s interesting to me because reading something incredibly well written or getting a fantastic take on something or writing an incredible investigative piece, obviously still gets my blood pumping, but that’s just money. That’s just spending money. What’s amazing is turning that into people who want to come into your village and never leave and move in and build a house there.

But I’m really in admiration, and I was listening to the first episode of this podcast which I really loved the energy of it. I loved the discursive thought of it. I happen to know Radhika (Jones) so I know the way her mind works and getting her to ruminate on being a reader and thinking about what she’s doing with Vanity Fair was so cool because I read every one of her editor’s letters and I know how she’s thinking about it.

And to me, what’s cool about how she’s brought herself to Vanity Fair is that she has changed Vanity Fair more than it has changed her. And I think that’s an incredible sort of staggering accomplishment. And I think Tina Brown did that. And I think there are eras in which you have somebody with a vision who kind of rots it into being. And I think that’s really cool. And I think that’s what I think about a lot. And what gets me super excited about the continuing Racquet project.

And when it’s time for me to step away from it, when I feel like all of these boxes have been ticked, and somebody else with far more fortitude and willpower and skills in math, certainly is ready to take it over and I can either work for them or like check in once in a blue moon. From the tennis court, preferably, like it will be when we’ve built a big enough tent that everybody feels like there’s a place for them in it. And until then I’ve got my work cut out for me.

Arjun Basu: How has the industry itself, the tennis industry, greeted it and the players too? How do they feel about it?

Caitlin Thompson: That’s a great question because, with no bitterness, I will say that at the same time as we were connecting with all these cool creative directors and hipster folks and like people who were culture tastemakers, but not necessarily endemic, like tennis diehards, the tennis industry space with a few exceptions was like openly hostile.

And I can only really chalk that up to the fact that I’m a loud woman, which, I’m not everybody’s cup of tea. Which, fair. But also this sport, unlike all of the other mainstream sports, tennis is the third most popular global sport. It’s crazy that it has a governing body—talk about a three body problem—it has a seven body problem. There are seven governing bodies in tennis, none of which are on the same page. Remotely. And they’re currently…

Arjun Basu: I think the bigger the sport, the more screwed up the governance is. I think of something like soccer and it’s just insane how badly soccer is run.

Caitlin Thompson: Sure. FIFA seems like it’s straight up Cosa Nostra, which, you know. But tennis has been so badly run to its own detriment for a long time. And the amount of money that these guys are leaving on the table and the amount of growth that the sport should have had, given its inherent popularity, it is honestly a little criminal. And so coming into essentially a bit of a backwater and expecting folks to be like, Oh, I get it. You guys are like Hypebeast or High Snobiety, or you’re trying to do what Tyler Brûlé did at Monocle or you guys are wanting to be the Vanity Fair tenants.

Like I get it. Guess how often that happened? Not at all. Maybe two people were like, Oh yeah. Okay. Because they had spent only their entire careers in the tennis space. Most other sports, yes, as corrupt and as top heavy and inefficient as their governing bodies are, at the very least have optimized for profit and growth and tennis has done neither. And in my view—and I was alluding to this earlier with the kind of shrunken pie—the people were fat on the land. We’re happy and there weren’t enough, honestly, smart disruptors around them to be like, Hey, this pie should be a lot bigger.

This is really actually criminal what you guys are doing. And why aren’t we connecting the pro game to the recreational game? Why aren’t we trying to grow in new markets? Why aren’t we? Because everyone’s self interested and they don’t have a lot of infrastructural motivation or benefit to collaborating.

And so it’s starting to happen now. It’s happening very quickly in a way that scares almost everyone in the tennis space, which I’m delighted by, because chaos is the latter (TK) after all. But it has been artificially depressed by a bunch of boobs at the top. And because of that, our appearance on the scene was viewed as unwelcome at best and pestilent at worst.

And, because we were asking hard questions, we were like, “Why are these people credentialed? This media center looks pretty dusty.” That’s saying something because I covered three presidential elections with the Washington Press Corps. Like that’s an old dusty crew. Tennis makes Washington, DC coverage look like the United Colors of Benetton.

Like it’s really nuts. And so that’s slowly changed. But one thing that helped it change was the players. The players are smart. This generation of players who’ve grown up having a direct relationship to the audience has no patience for the gatekeeping and kind of ham-fisted marketing efforts that the sport has tried to put around them because they don’t need them. They can just do it. Talk to their audience directly and their authenticity is their selling point.

And I think the first couple of athletes started working with us because they sensed that we could give them dimensionality in a way that sports media had never—I don’t want to generalize a lot of sports media had, but in other sports, just not tennis—but we gave them dimensionality. And a lot of times with the smarter or more creative ones, we gave them the opportunity to be creators themselves.

We started publishing long form journalism written by Andrea Petkovic that has won awards. And now she’s written two books of fiction in Germany because now she’s like a credible author. And the same for…

“We are changing tennis. We are changing the conversations around it.”

Arjun Basu: Yeah, Naomi Osaka guest edited an entire issue.

Caitlin Thompson: Stefanos Tsitsipas taking photographs. Players started getting onto us early because I think they realized like, “Oh, I could listen to my agent and go do like a bunch of sound by interviews with pre-selected questions, vetted my agent, or I could do something direct to the audience or even better with these folks who are going to make me look cool and interesting and human.”

And I think they have a lot less fear than the generations prior of looking bulletproof because I think they realize that their selling point is their authenticity. And I have this ongoing debate with my wife about how destructive the internet and social media are. And I think for the most part, she’s probably right. And we’re all in a doom loop.

However, there are certain parts of the media that have really benefited from the lack of gatekeeping. And I think one of them is the authenticity of the direct conversation between a notable person and their audience. Not to say that all of them are authentic, not to say that all of them practice this, but that is even as an acceptable form of dialogue, gaining popularity and changing a lot of the ways that those of us in the professional manufacturing of journalism have had to reapproach our jobs is, in my view, net positive.

And so the players getting onto us, the players wanting to work with us, the players asking their agents, or sometimes they’re shooing their agents entirely, or bringing their brands along, really helped because when we would say, “Hey, we have an idea,” the player would jump at it, and we wouldn’t have to wait for 18 gates to open because a bunch of unimaginative sports agents who are among the most basic people in the world in my experience—these are not people who want to take leaps or reinvent wheels—but the players in a lot of cases are, and they would directly dialogue with us. And I think that has helped change the overall tennis universe to, I wouldn’t say point favorably in our direction, but we’ve benefited more from it in the past couple of years because I think they realize: Oh, this future is happening with or without them.

The players are going to do this with or without them, so they might as well get on board.

Arjun Basu: Tennis has two advantages. One, the players' personalities really are part of their game. You can almost see them think on the court. And the other big individual sport, golf, golfers aren’t really personality driven whereas tennis players are; and two, tennis just happens to be very aesthetically pleasing.

Caitlin Thompson: That’s right. It’s beautiful.

Arjun Basu: It’s beautiful, and it just lends itself to a magazine like Racquet.

Caitlin Thompson: I think that’s true, but I also think we have so many areas of white space that we should and can be exploring. Golf has managed to make the playing of it and the bucket list-esque travel component of it a near religious experience.

There are, like, three publications. I’m thinking notably of The Golfer’s Journal, but there’s a couple others where one’s participation in it is just as important as the stories around its professional practitioners. That’s fascinating to me and something that tennis has a long way to go and we want to be on the forefront of providing.

It’s beautiful. It’s also solitary. And I think it really has been underserved by really unimaginative press and unimaginative agents, and I think, yes, it photographs well, but also, it’s I think remained somewhat one dimensional because of a lack of imagination.

And so when you try to do a documentary project, or you try to get one of these folks on the microphone, or you try to get some insight into their sort of pugilistic, rivalries with each other, or the way that they had processed some of the things that had happened to them—outside Andy Murray, who can’t help but be completely candid and obviously has overpowered any agents attempt to muzzle him—you would get like really boring corporate answers.

And I think those folks were more interested in making sure that the deal flow kept coming then they were of being interesting and vulnerable. If anybody needs evidence of this, try to watch the Serena Williams documentary. You can tell it was executive produced by IMG and Serena Williams. Like it’s cool. She’s cool. Her house is beautiful. She hits the ball better than any woman who’s ever walked the planet, but there’s no human revelation to that.

And I think I’m relieved that era is over. Not because it wasn’t great to experience their tennis and watch it and be part of the stories, it’s because we didn’t really get inside of them. And for me, what is so much more interesting is not the actual individual player, but the game itself. And I think one of the biggest things tennis actually has going for it is that if you sit courtside up close next to any two professional people, or four in the case of doubles, and you watch these people hit tennis balls and you understand how difficult what they’re doing is it’s not captured on TV, not close.

Then it feels like you’re in the center of the earth. And I think the truth of that is there is so much more that we can and should be teaching and showing that, to me,the sky really remains wide open with possibilities.

“Tennis deserves something really big and they’re not going to build it themselves.”

Arjun Basu: So what does the future of Racquet look like? You had a little drama last year and you came out of that and everything’s good. What’s on deck?

Caitlin Thompson: Yeah. I think, I would say with regards to, do you want to build an art project or do you want to build a brand?

Not everybody is built for every part of every journey. And I think with respect to everybody who’s been part of the earlier iterations of Racquet, who’s who you know, maybe you’re not part of things currently like, much love much respect, but also this is built to be a bigger thing and I think that requires a ton of hard work. And it’s not a hobby.

It’s a day-in-day-out exercise and empire building. And, that’s not for my own personal edification, but I think it’s because that’s what the sport deserves. And that’s honestly like the only way to really make a go at media right now. I think if you’re not going big and you’re trying to do what Ben Smith is trying to do at Semafor where you’re, yes, doing incredible reporting and breaking news and doing newsletters, but also having events and trying to get giant sponsors across your multiple platforms so that you can sustain and pay those journalists so you can keep doing amazing work so you can keep growing—or what I see the folks at Airmail doing where they’re going into brick and mortar, where they’re doing more events, where they’re doing direct retail, in addition to a lot of the branded stuff.

But tennis deserves something really big and they’re not going to build it themselves. And so for me until that day comes where we’ve ticked all of those boxes, it’s expanding internationally. It’s getting into the club space and making an experience work so that you, Arjun, get off the plane with your racket and you find a club and a community and a place to play within 30 minutes.

It’s making the creative agency work with the collabs, all of which is sustaining really good journalism that is breaking news, but also pushing the sport further and further into the right direction. So unless it does all of those things, I’m not interested.

Arjun Basu: I always end these with a standard question. What are three magazines or media you’re consuming now?

Caitlin Thompson: One of my favorites is Apartamento, the Barcelona based home ecosystem. I love the way that, first of all, it offers a vision of a future after Racquet gets to where it wants to be and I have successfully placed it in the hands of someone very competent who will take it to further and further heights than I could ever possibly have achieved.

And I live in Barcelona and I have an incredible apartment, in El Poblenou, three blocks from the beach. I just so admire how much of a world they’ve built around this concept of the home as a form of intimacy. And I’m not a particularly visual person. I’m not a particularly interiors-focused person, but the entirety of the world that Apartamento has built: the books, the brick and mortars, you go to Casa Bosque in Mexico City, you can go to the Apartamento office, as I’ve been lucky enough to do. And you just see how it all interconnects. I really admire when people can make their vision writ large on a couple of different planes. And so not only is the book itself just a joy to consume and it’s escapist in all of the best ways, it feels truly like it’s part of a larger world that you can get lost in.

One of the reasons I read so much fiction is I love getting lost in worlds. And for me, particularly with magazines, if I feel like you’ve built me a palace of ideas that I can wander through, that hearkens back to the things that excited me about my early days at journalism school, dissecting magazines and mastheads, because it’s something that you feel like you can be a part of.

I’ve mentioned Radhika’s Vanity Fair, I mentioned David Granger’s Esquire, I mentioned obviously what Anna’s doing, with Vogue and GQ to a degree obviously though, hats off to Will Welch. But I think the thing that I consume the most with just pure, unadulterated joy is Apartamento.

Arjun Basu: That’s great. That’s a great answer. And this was a great conversation. Thanks Caitlin.

Caitlin Thompson: Thank you. What thoughtful, amazing questions. Thank you so much.

Caitlin Thompson: Three Things

For more information visit Racquet online.

More from The Full-Bleed Podcast