Last Call

In 1999, Dan Okrent saw the future of the magazine business and raised the alarm. Very few paid attention. And now you’re listening to a podcast called Print Is Dead.

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE SOCIETY OF PUBLICATION DESIGNERS

Back in April, 1966, Time magazine famously asked America the big question: “Is God Dead?”

Thirty years later, as Time Inc.’s Corporate Editor at Large, Dan Okrent posed an equally existential question: Is print dead? His answer: An unequivocal “yes.”

“Finished. Over. Full stop,” he declared in a 1999 lecture at the Columbia School of Journalism.

Despite that, it’d be unfair to call Okrent the Grim Reaper. (Just don’t ask what he said about Detroit in the early 2000s). A lifelong realist, Okrent simply viewed digital delivery as the most sustainable path forward for magazines, thanks to the skyrocketing cost of paper, printing, and postage. Publishers, however, ignored Okrent’s prophecy, and continued to feast on their circulation revenues while treating their digital efforts purely as supplemental to print.

“How do you say goodbye to that cash? You don’t. And then you end up seeing what happened in the slaughter of the next 10, 15 years. And this was before the smartphone!”

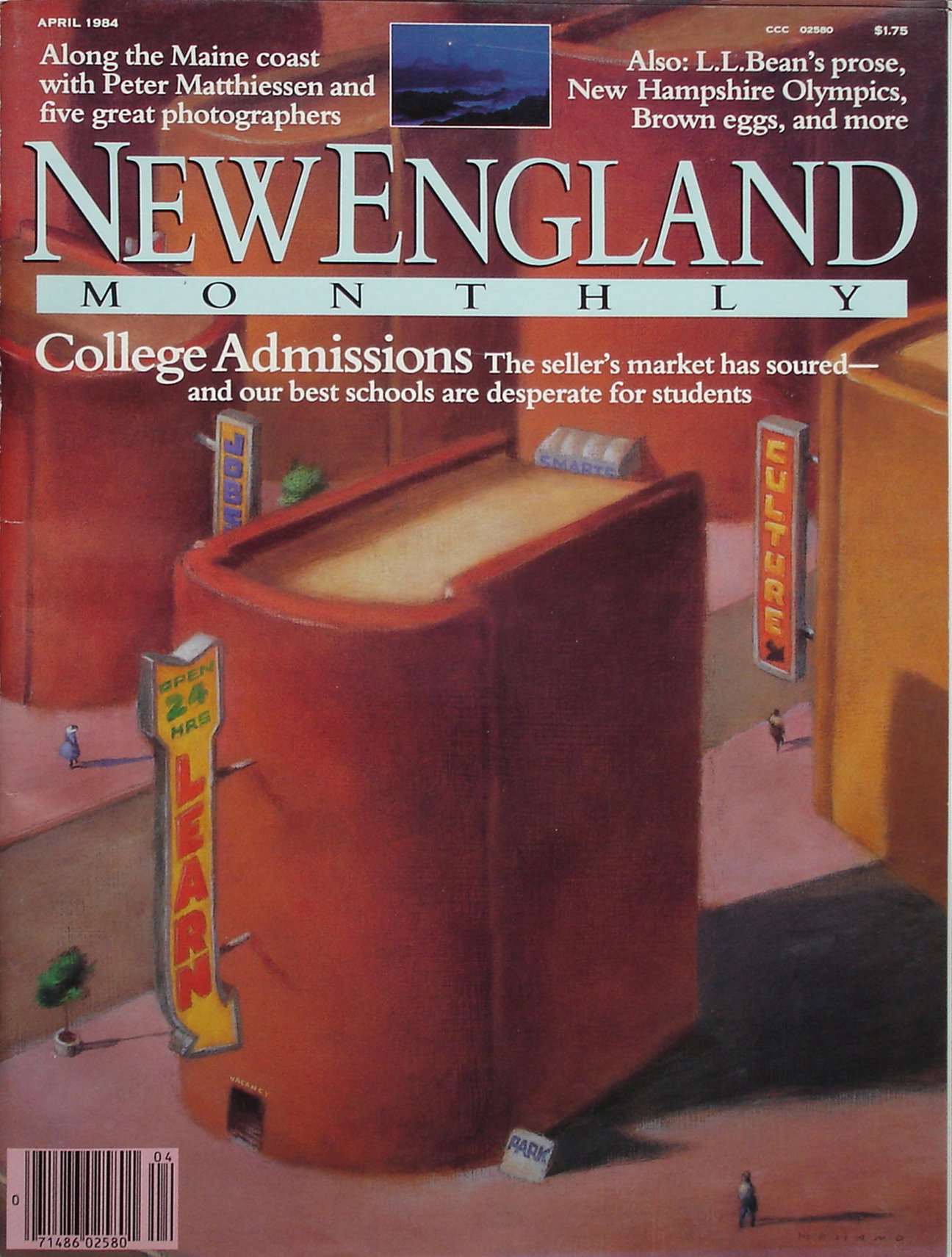

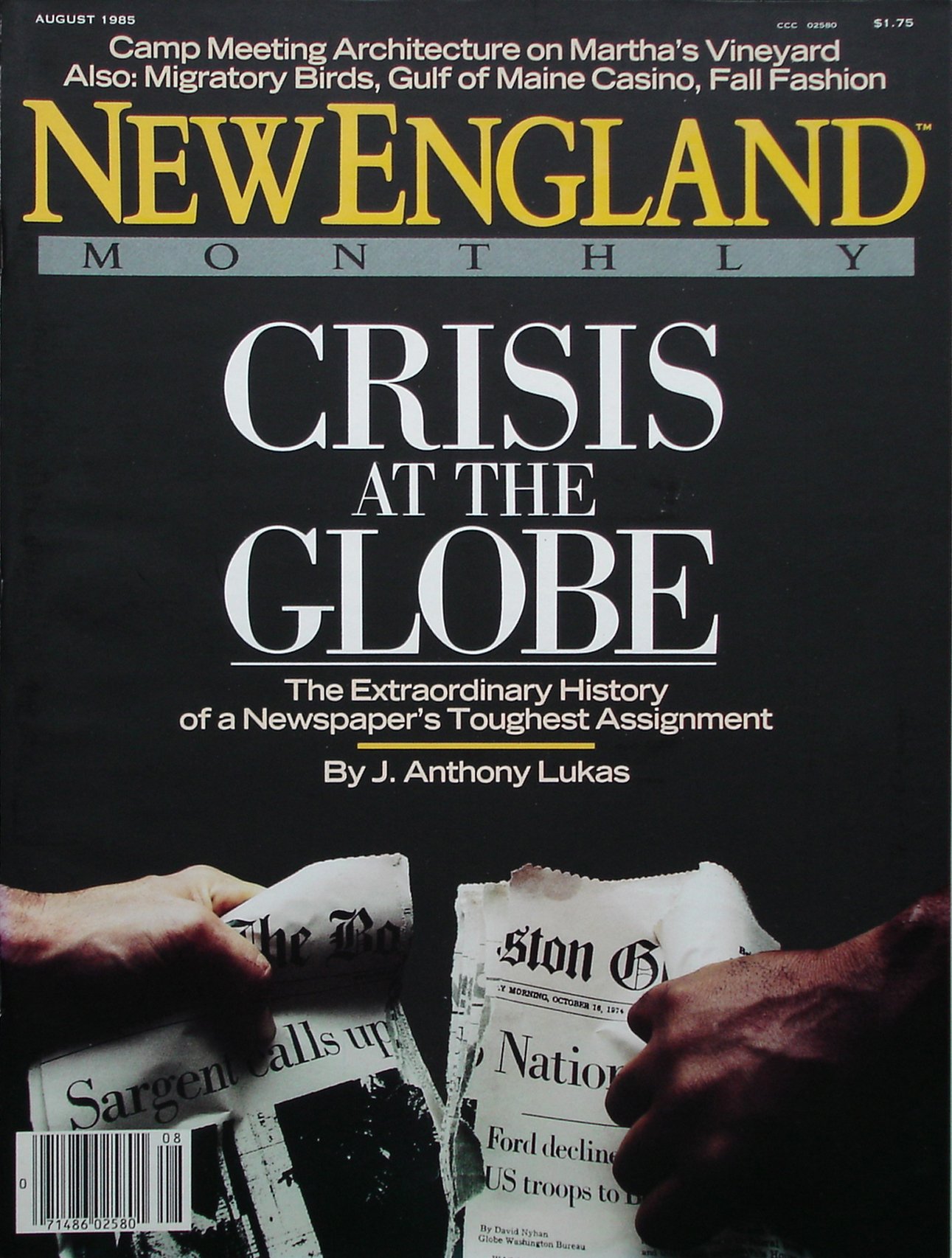

Okrent made his name as the cofounder of the highly-acclaimed regional, New England Monthly, in 1984—his first job as a magazine editor. He went on to work at Time Inc., Life magazine, and The New York Times, where he served as ombudsman in the wake of the Jayson Blair plagiarism scandal.

He’s the author of numerous books, including Great Fortune, a 2003 history of Rockefeller Center that was shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize.

In this episode, Okrent talks about his personal board of advisors and the roles they’ve played in his life, about his career highs and low—including a “humiliating” bake-off he was part of when Sports Illustrated was looking for a new editor, about how he introduced the world to fantasy sports, but didn’t make a dime, and how he later pivoted to fame and fortune “off” Broadway.

“If management had said, ‘Okay, I’m prepared to lose a couple billion in the next five years, but I’m going to convert.’ The business would be better off today. That didn’t happen.”

George Gendron: The first time I heard anybody publicly use the expression “print is dead” was 1999, when friends of mine, colleagues of mine, started talking about a speech that you had given, I think it was at Columbia journalism school.

Dan Okrent: Right. It was the Hearst Fellowship speech at Columbia.

George Gendron: Yeah. So that’s ’99. And you had done something that we journalists have been known to do in our packaging, which is you had very cleverly put a question mark at the end of the title “Print Is Dead.” But it shook up a lot of people, because we were in the early stages of preparing Inc. for a sale. And we had Goldman Sachs representing us, and they were telling us that we should expect somewhere between $175 and $250 million.

Dan Okrent: I was on the other side of that, because I was part of the conversations with Time Inc. at the time.

George Gendron: Yeah. So you guys actually, technically, AOL, was the number-two bidder for Inc. We ended up selling to Bertlesman, the German publisher, and that ended up being very, very lucky for us. And nothing more than luck because they were private. And so it was an all cash deal.

But that still gives you an idea, you know, you’re up there at the podium at Columbia saying “print is dead.” And we’re down here preparing with Goldman for an auction where people are telling us you can expect a quarter of a billion dollars for the magazine.

And so when you were organizing your thoughts for this presentation, what was the catalyst? What were you seeing that other people in the industry simply weren’t seeing at that time?

Dan Okrent: What I was seeing was paper, printing, binding, and mailing. And knowing how much money—Time Inc., spent something like $400 million a year on the physical product—for all the Time Inc. magazines to get them into the mail. Well, first, off the printing press and then into the mail or into newsstands.

And, somebody came to me and said, “I can save you $400 million every year by sending this thing out digitally.” I said, “Well, shit, of course.” Excuse me. “Well,” I said, “Of course I would do that.” It just seemed that we were in the business of words, images, ideas.

We weren’t in the business of cutting down trees, or formulating ink, or running a post office. So, you know, if there had been no other talk about the digital world, and it was just something that came in overnight and you were able to walk into your publisher’s office and say, “How would you like to save this?” And you said, “Sure, that sounds like a great business to me.” But the problem is that too many of the print companies followed the path of the record companies who were destroyed by digital distribution because they said, “Oh, this isn’t going to happen.”

The CEO of Time Inc. when I was there in the ’90s, was the smartest man I’ve ever met in the publishing business.

George Gendron: Who was that?

Dan Okrent: Don Logan. From Alabama. He grew up in a house that had a dirt floor. He did not think conventionally. He did not buy into all the, you know, the holy writ of the publishing business. Very, very practical, brilliant businessman. And he was the one who famously said that his company was, you know, pouring money into a black hole and trying to develop stuff for the web. If, at the time, you walked in or I walked in and said, “I could save you $400 million—if management of those companies had said, “Okay, I’m prepared to lose a couple billion in the next five years, making the conversion, but I’m going to convert.” The business would be better off today. That didn’t happen.

George Gendron: No. We thought we were smarter than the rest because we had been an early mover digitally with Inc.com, and we had a very vibrant site thanks to two technology editors that we had that were really quite brilliant and prescient. But we still clung to the belief that the cornerstone, if you will, of the brand was going to be print and that digital would somehow play an ancillary supplementary—important—but supplementary role.

Dan Okrent: That’s exactly my point. That’s what all publishers did. And the reason why they did it—there was a certain logic to it—was it was protecting this incredible cash flow. The cash flow was coming in. And there’s nothing like cash flow in the magazine or newspaper business.

If you’re, I don’t know whether listeners are aware of this but the circulation money comes in before you print the magazines, before you pay your salaries. That is just fantastic cash. So how do you say goodbye to that cash? You don’t. And then you end up seeing what happened in the slaughter of the next 10, 15 years.

George Gendron: That’s right. In fact, it resembles what people to this day still pursue in terms of a business model, which is a membership model, right? Pay upfront, and then use or consume the product later. And on top of that, think of a magazine like Inc. When we wrote 650 ad pages in a year, we had all of our overhead covered. So every ad page, every incremental ad page after that, all we were doing was paying two things: we were paying the commission to the sales guys and we were paying the cost of the paper.

You talk about margins. This was just incredible! And it was inconceivable to us that this wouldn’t continue.

Dan Okrent: Right. And Time Inc. was an odd man out in the publishing business. Condé Nast was the same way. A certain number of ad pages were done. Condé Nast was charging a dollar an issue for big, fat magazines. Time Inc got 50% of its income from circulation. It was much more reader dependent than advertising-dependent than most. So multiply however you felt about all that cash pouring in after you’ve covered your costs. And that was Time Inc., which was a $2 billion a year business at the time.

New England Monthly (1984-1989)

George Gendron: We heard rumors, from well-placed sources, that there was a business weekly that was paying $150 to acquire a subscriber. When, I think, the subscriber was paying, I don’t know, $35 for 52 issues a year. And then of course the equation was, “Well, how much can we resell that subscriber to the advertiser, period?” And that’s where the multiples were.

I reread your speech last night. And the first thing I have to do is fact check you. You said at the time, and I’m sure you were more accurate then than you are now, Time Inc was spending a billion dollars on paper printing and distribution. A billion dollars a year.

Dan Okrent: Okay. So I was accurate then. But, Jesus yeah! A billion dollars a year! Let’s save that money and just do things in digits.

George Gendron: Yeah. So what was the response of the audience? And what was the response of your colleagues back at Time, Inc?

Dan Okrent: The audience was, I say somewhere in the speech that, you know, this is not going to happen in my professional lifetime, but it will for a lot of the people in the room, because there were a lot of 23 year old graduates in the room. And they were nodding their heads. I mean, I can’t characterize all of them, but it was a pleasant reception.

At Time Inc., Don Logan and Norm Pearlstine, who was the head of the editorial operation, they thought I was nuts. I had this conversation with Don. He bought the logic. He understood. “You can save me a billion dollars a year, but,” he said, “Will people want to read this way?” And as I say in the speech, you can’t make predictions based on today’s technology. And today’s technology is... who’s going to schlep around a computer to read on a flat screen? And this was before the smartphone. So that changed everything. And none of us was anticipating that to happen soon. It did happen.

George Gendron: Looking back, as you recall the speech, what’d you get wrong?

Dan Okrent: Well, I had this notion that all these signals were going to come from satellites, you know, there’s Telstar—Sputnik!—up in the sky that is beaming my issue of Time magazine, or whatever else I’d be reading or watching, down directly to my laptop. That was very wrong.

George Gendron: It made sense at the time.

Dan Okrent: Well, who had ever heard of “the cloud?” I mean, the people who invented the cloud hadn’t heard of the cloud at that time. So that’s one thing that I definitely got wrong. I also predicted that it would be a flexible screen that you could roll up and put in your pocket like a magazine. That, to my knowledge, has not happened. Or, if it happened, it disappeared quickly. So that it would have the same feel as holding a magazine in your hands. I’m sure you noticed many other things I got wrong. I’m not recalling them now.

George Gendron: No. I think one of the things that struck me was something that, again, made perfect sense at the time because there were already trends in this context, and that was publishers would give the hardware away. You know, like a razor blade, basically.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. That didn’t happen. It didn’t quite happen. There are some versions of that. Not exactly publishers, but, for a time AT&T did own AOL, and they were giving away phones.

The thing that I got right, if I may pat myself on the back, was that you would have a choice. Do you want to pay for it or do you want advertisers to pay for it? If you’re tired of the advertising you’re seeing, send a check—digitally, of course—and you can get it without advertising.

And, of course, that is ubiquitous on the web. You want the premium version? You don’t have to look at ads. In other words, asking the reader to pay for the product, not asking the advertiser to pay for a reader.

George Gendron: Yep. And of course, that dynamic’s still playing itself out, right?

Dan Okrent: Absolutely.

George Gendron: One of the things that really interests me is that those of us in the media have tended to pay an enormous amount of attention, obviously, to the shift from one medium to another. But that’s only part of the story.

Meanwhile, something else that’s been far less explored is the whole issue of what people, when they buy a book, whether they’re going to read it in print or whether they’re going to read it on Kindle, how their expectations have changed and how younger people are using media in a way that’s completely different.

So this isn’t any longer about print is dead, analog versus digital. This is something else. And I know you have thoughts about this.

Dan Okrent: Well, as you say, it’s generational. People of our generation, we have always approached—and I don’t want to use the word print—media that isn’t broadcast, that isn’t video, words on paper. We are still, many of us today, approaching it the same way we did when we learned how to read at four or five or six.

You pick up a book and you go page by page through it, and then you complete the book. Or you get a magazine. You may not go every page through it, and you got The New Yorker when you’re 14 for the first time, you go look at the cartoons and then maybe go back. These moves, these modes of connection with the reading material do not exist for the rising generations. They did not begin that way. They began, or are beginning, with a smartphone in their hands.

And thus the things that one might read, as opposed to those things that one might watch like TikTok—the things that one reads one is reading it in a very different way. It’s small bites, obviously. It’s instant gratification. You look at something like time.com, which is a fairly healthy website with several hundred thousand paying customers, they’re updating, not just on a daily basis, they’re doing things during the day.

This was a publication that came out once a week. You edited a publication that came out once a month. But for the audience who we have today, you give them just something once a month, you don’t have an audience anymore.

So you look at The Atlantic. Now, obviously, The Atlantic benefits from having a billionaire behind it. But The Atlantic was once this staid thing in print that came once a month. Now it comes—every half hour there’s something new in the atlantic.com. And that’s the way that young people, I believe, are learning how to read and learning how to deal with what we called print media.

George Gendron: And, as we discussed, I think you could just say this is how young people are learning, period.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. Well that, that, that’s it. It used to be, in my case, if I wanted to learn something, I’d say, “Well, jeez, I’ve got to go to the library and get a book about this? Look on my shelves?” Now I just go to Wikipedia! It’s again this instant gratification. It’s so possible to do that. The book I’m writing right now—I go back to my first books and everything was, you had to go to a library, you had to go interview somebody. I’m doing it all in digits now. I can do all of my research in digits.

George Gendron: Can you share what the book is?

Dan Okrent: This is a short biography about Stephen Sondheim for a Yale University Press series. And I needed to do work in the Leonard Bernstein archives because Bernstein and Sondheim were very close for many years.

Previous books, I would go to the Library of Congress. I’d travel to Washington. I’d get a hotel room and do it there. Now it’s all online. I don’t have to go anywhere. It’s fantastic.

It’s bad for hotel business, but it’s certainly good for me. The ability to grasp information when you want it, in the form you want it, is something that is utterly revolutionary.

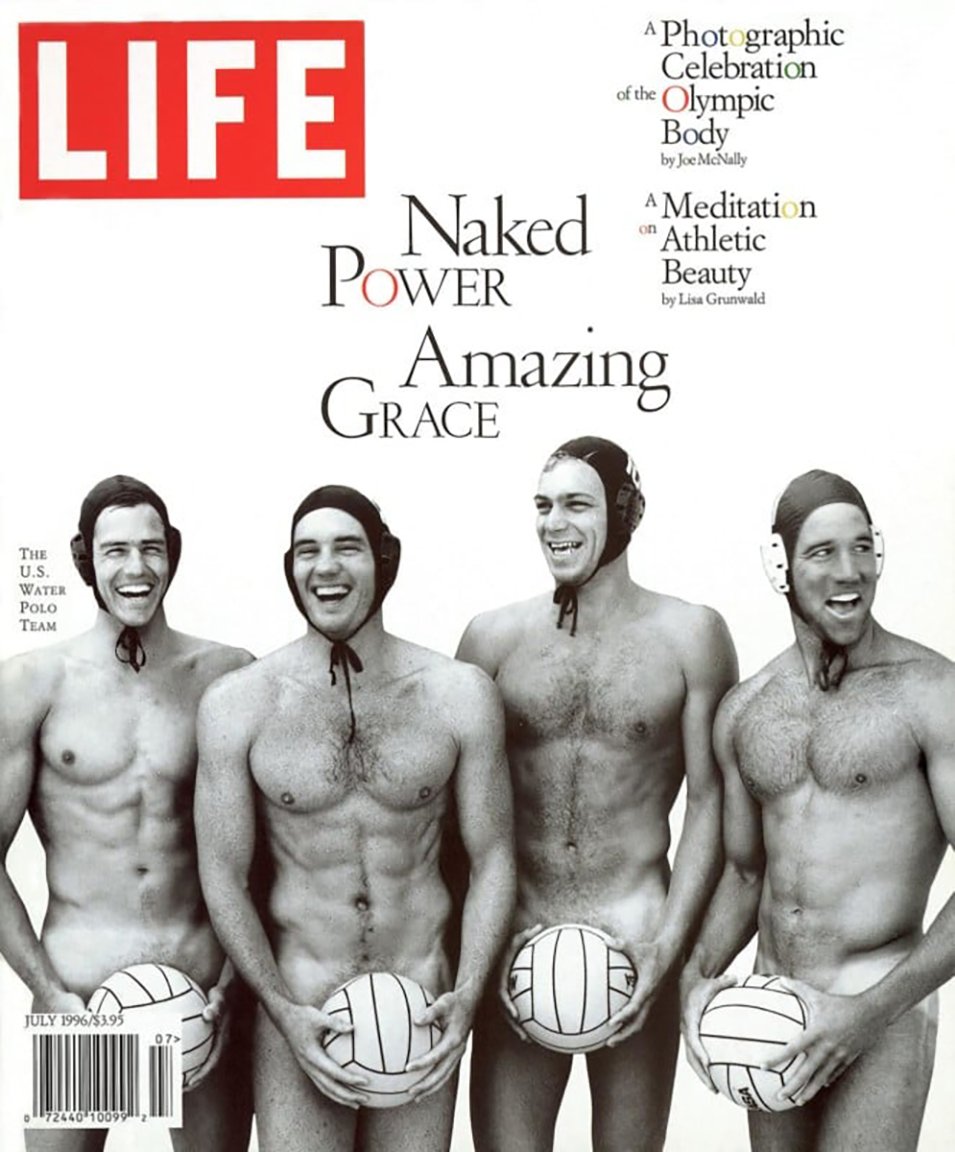

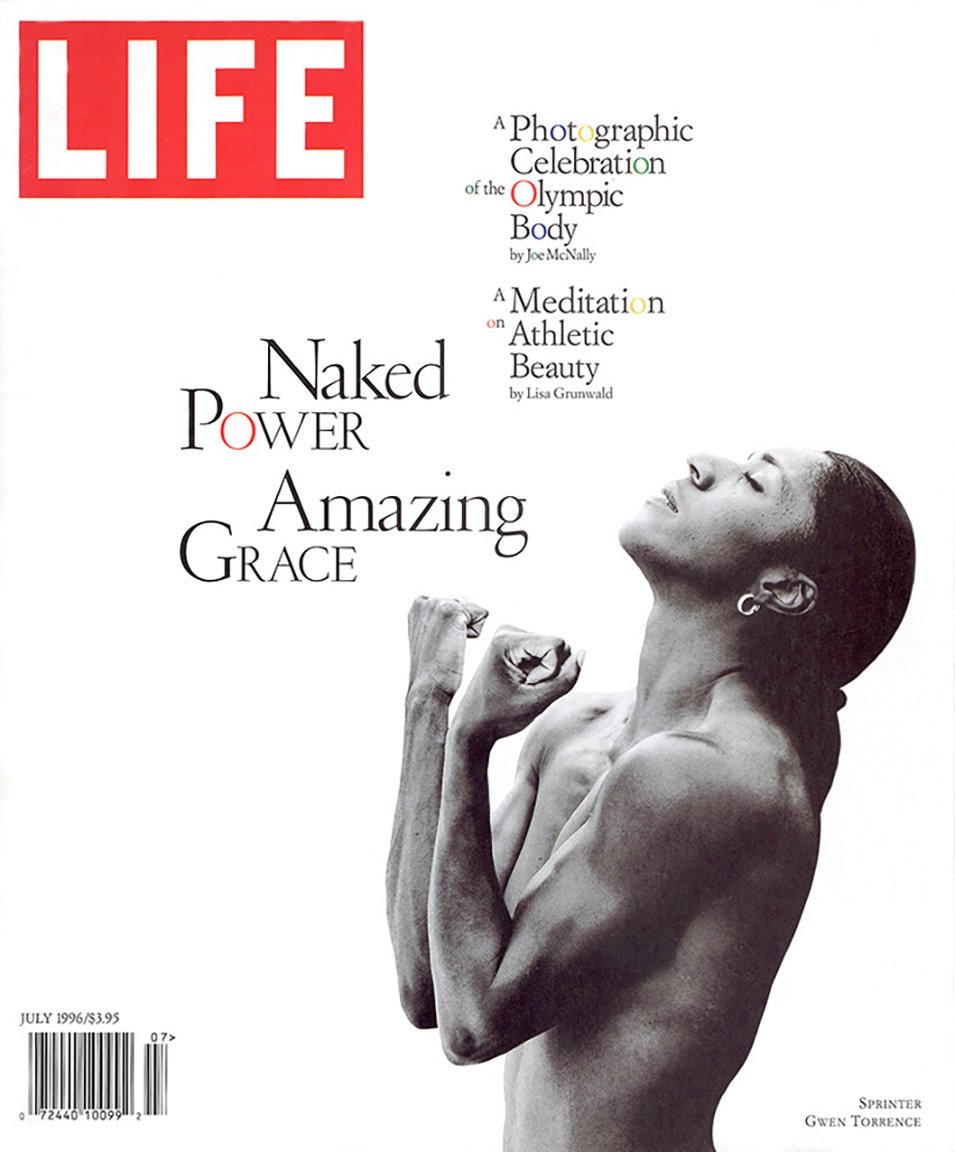

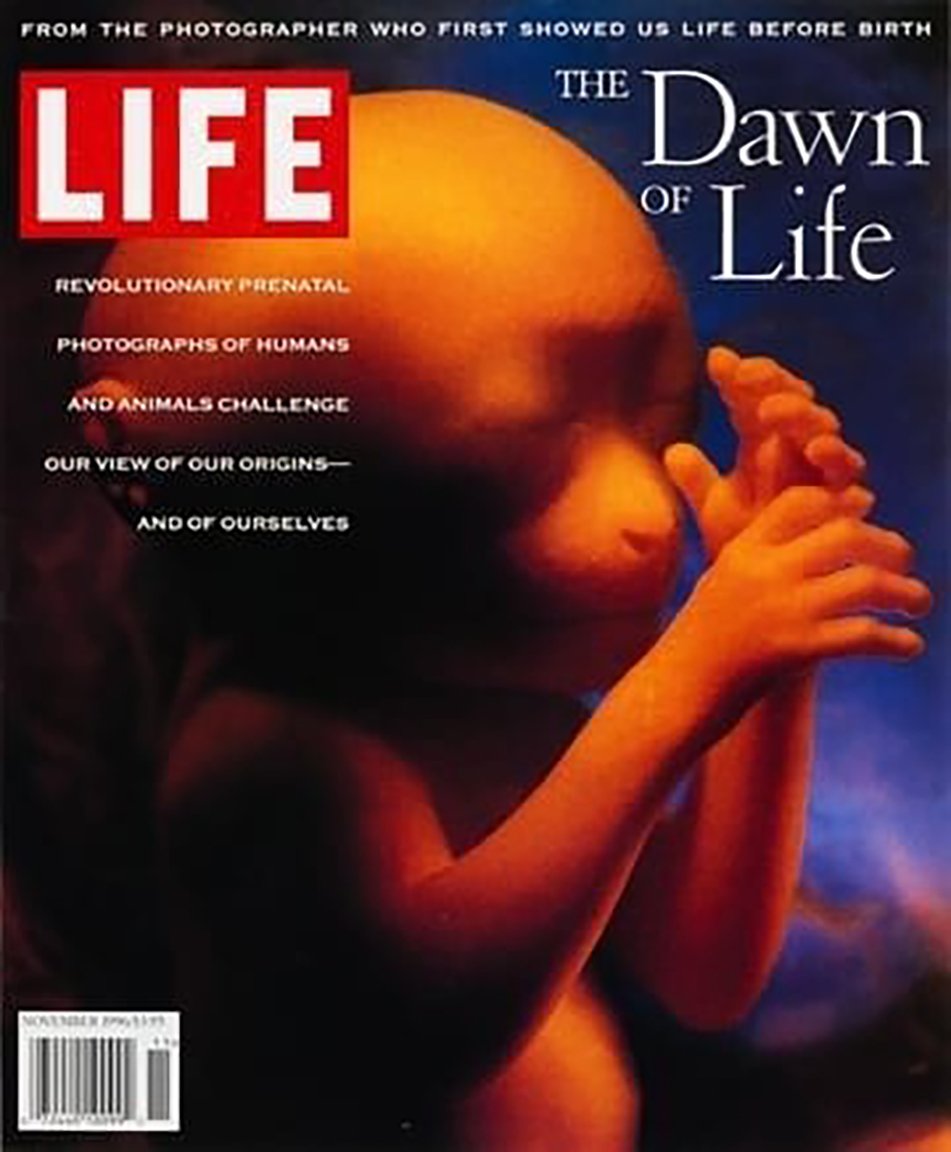

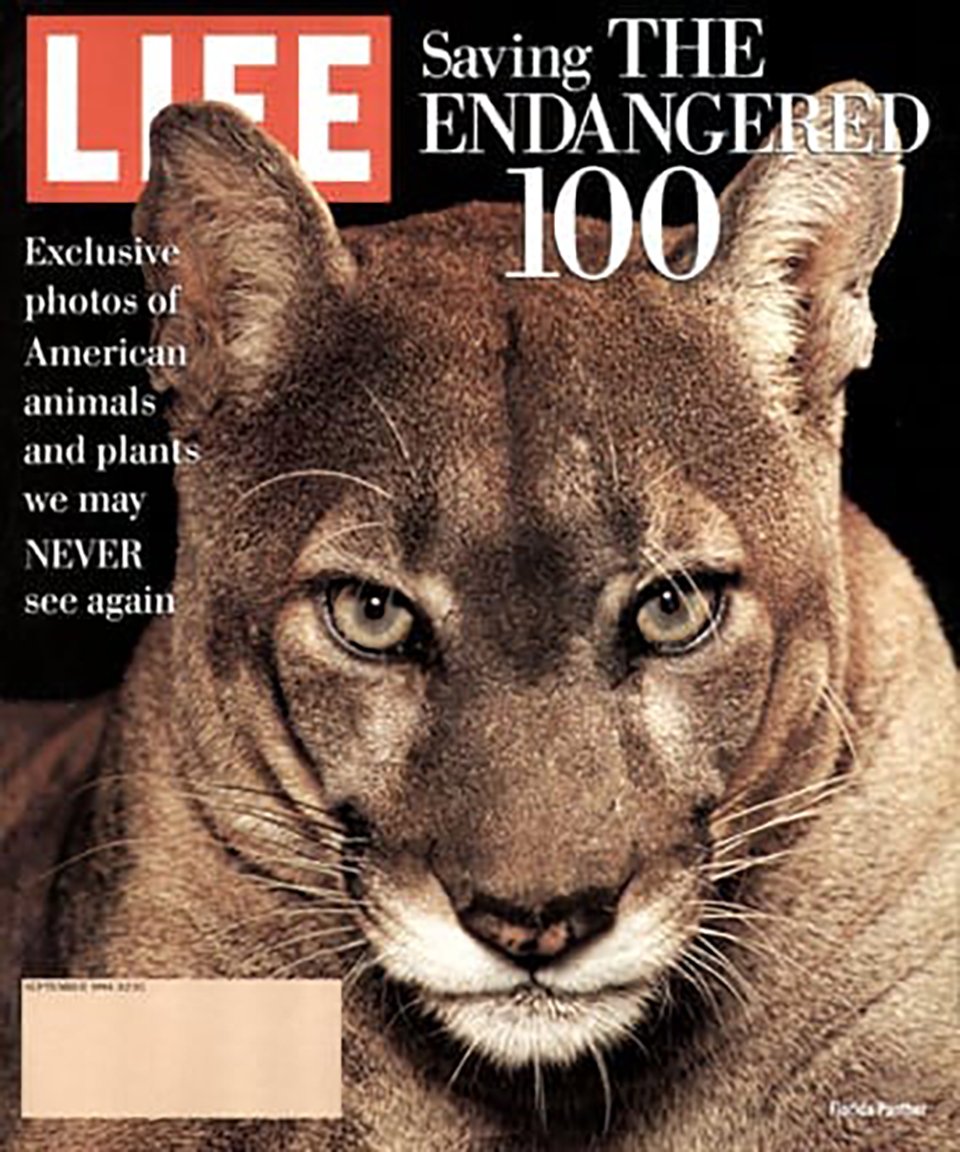

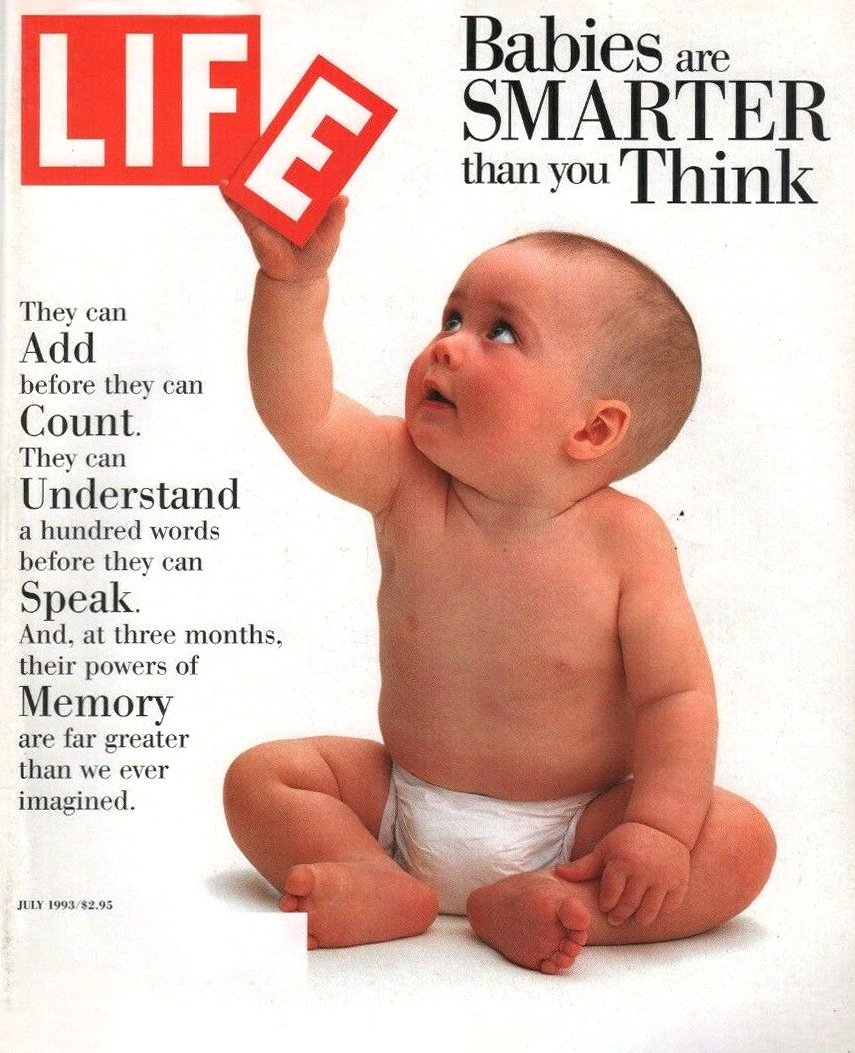

Life Magazine (1990-1997)

George Gendron: I want to come back to this in a different context later on in the conversation when we talk about one of your books that is my favorite of your books. But right now I want to shift gears a little bit and talk about naïvete, which is something that I think is not widely shared. And yet almost everybody I know has at least one major episode. I have several. I think you have—I’ll call them “multi-industry” examples of how naïvete helped shape the arc of your career. So I’d love you to start with how you got into the book industry and became a book editor in the first place.

Dan Okrent: I read an article in The New York Times. I was an undergraduate in the University of Michigan. I was the book review editor, among other things, of the student newspaper. I read an article on the front page of The New York Times Book Review one Sunday about Joseph Heller and how Catch-22 had made him into a major American novelist, his agent, Candida Donadio, the leading fiction agent in New York, and his editor Robert Gottlieb, the fiction power who had just moved from Simon & Schuster to Knopf, at the age of 37, I believe.

I said, “Book editor?” I’m from Detroit. I didn’t know that books had editors. What does that mean? I thought, you write a book and then it comes out. I just had no idea at all. So my first naïve step was to write a letter to Gottlieb. He got many letters. But the rest of them, most of them, were, “I’ve just gotten my master’s degree at Oxford and I’ve read everything in English literature since the 15th century.”

Mine was absolutely nutty and naïve and off the wall. And he said, “Well, I don’t have any jobs here, but if you’re ever in New York, let me know and I’ll be happy to talk to you.” This was the days of student standby airfares. So the next day, I took a bus to Metropolitan Airport, outside of Detroit, flew to New York, where I had been once, on my high school senior trip. That was the only time I had been.

I got off at LaGuardia and called Gottlieb’s office. And his assistant said, “Who are you?”

I said, “Well, I’m, I’m Danny Okrent from University of Michigan.”

“Do you have an appointment with Mr. Gottlieb?”

“No, but he told me to call him if I was in ...”

She put me on hold. He said, “Tell him to come in.”

She gave me directions, and I got there around four in the afternoon. We were still talking at seven when he said, “When do you graduate? Would you like to come to work here?”

It was really preposterous. But you make your own luck, I guess.

George Gendron: You know, some people who might have had a little bit more sophistication would’ve recognized Gottlieb’s line as a brush-off line: “If you’re ever in New York...”

Dan Okrent: Right, right. You, who live a thousand miles away. Right. That’s exactly right. 600 miles away. Yeah.

George Gendron: So you went on to have a very prosperous career as a book editor.

Dan Okrent: Hmm. I had a decent career.

George Gendron: Okay. Decent career. And a book author. And so, while we’re on this subject, I have to ask you from both a book editor’s perspective and a book author’s perspective, we’re back to this question of changing business models. How has the business changed?

Dan Okrent: The book business has changed in so many ways we would need hours to talk about it.

George Gendron: For you in particular. From, let’s say, from the writer’s point of view.

Dan Okrent: For me, I’ve been fortunate enough it hasn’t changed that much. I can get a contract. I can’t live off of it entirely. But so far I’ve been able to get decent money, and I turn in my books and they get published.

It’s a lot harder for people who hadn’t already established careers in the pre-Amazon days. But since Amazon, where, it’s a monopsony, where there’s one buyer. It’s not a monopoly, it’s a monopsony. There are many suppliers, but only one customer. And that has radically changed the business.

Publishers do not take chances—they take chances on extremely expensive books written by very well known people—but they don’t want to take a chance on the 32-year-old version of me. They can’t afford to. Their margins have been cut so sharply by Amazon’s power that they would only lose money on me. Even writing the same books that I’ve been writing.

“The freelancer’s life has always been pretty rotten. The very idea of ‘you write the piece today and I put the money in my bank for three months.’ That’s kind of disgusting.”

George Gendron: Yeah. I mean, from someone like myself, given the span of my career, I remember when I was running Inc. Magazine, I would have lunches with either agents or publishers who would start to talk about sums of money as an advance before we had ever talked about any concept. And it was because you’ve got a platform. And now it’s kind of, “Well, what’s your platform?”

Dan Okrent: Speaking of platforms, my first three books, I was fortunate enough to land, for publicity, on the best platform that existed, which was The Today Show. Boy, when the publisher sends out word that Okrent’s going to be on The Today Show in two weeks, the orders from the bookstores just pour in because it really sold books.

My last book, they didn’t even bother to pitch me to The Today Show. It was all about various web influencers—people I had never heard of—that if one of these people adopts your book and touts it, that’s the path to great success. So even there, the presence of books as they move through our culture is in digits. It’s not any longer coming across the way that it used to.

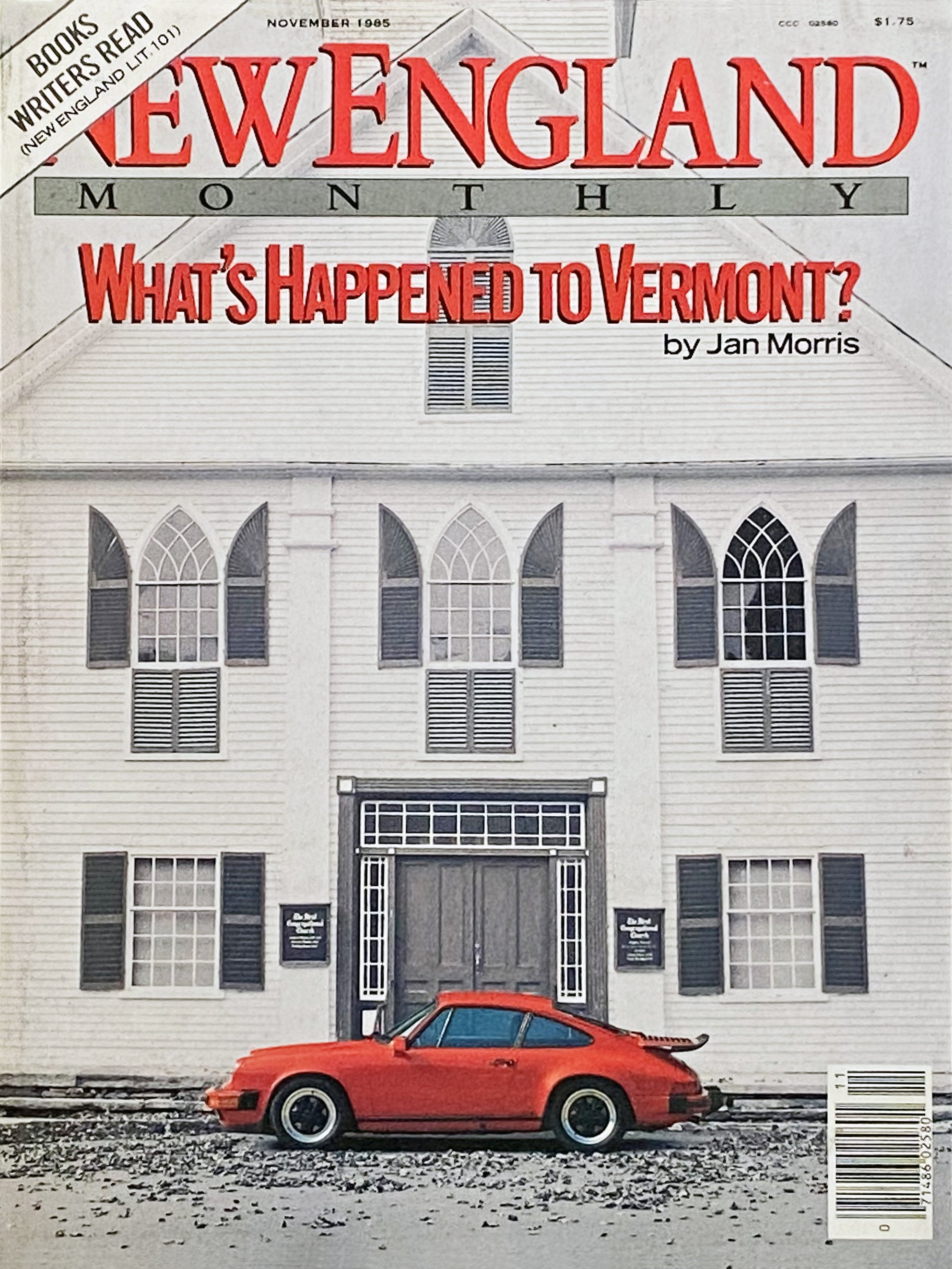

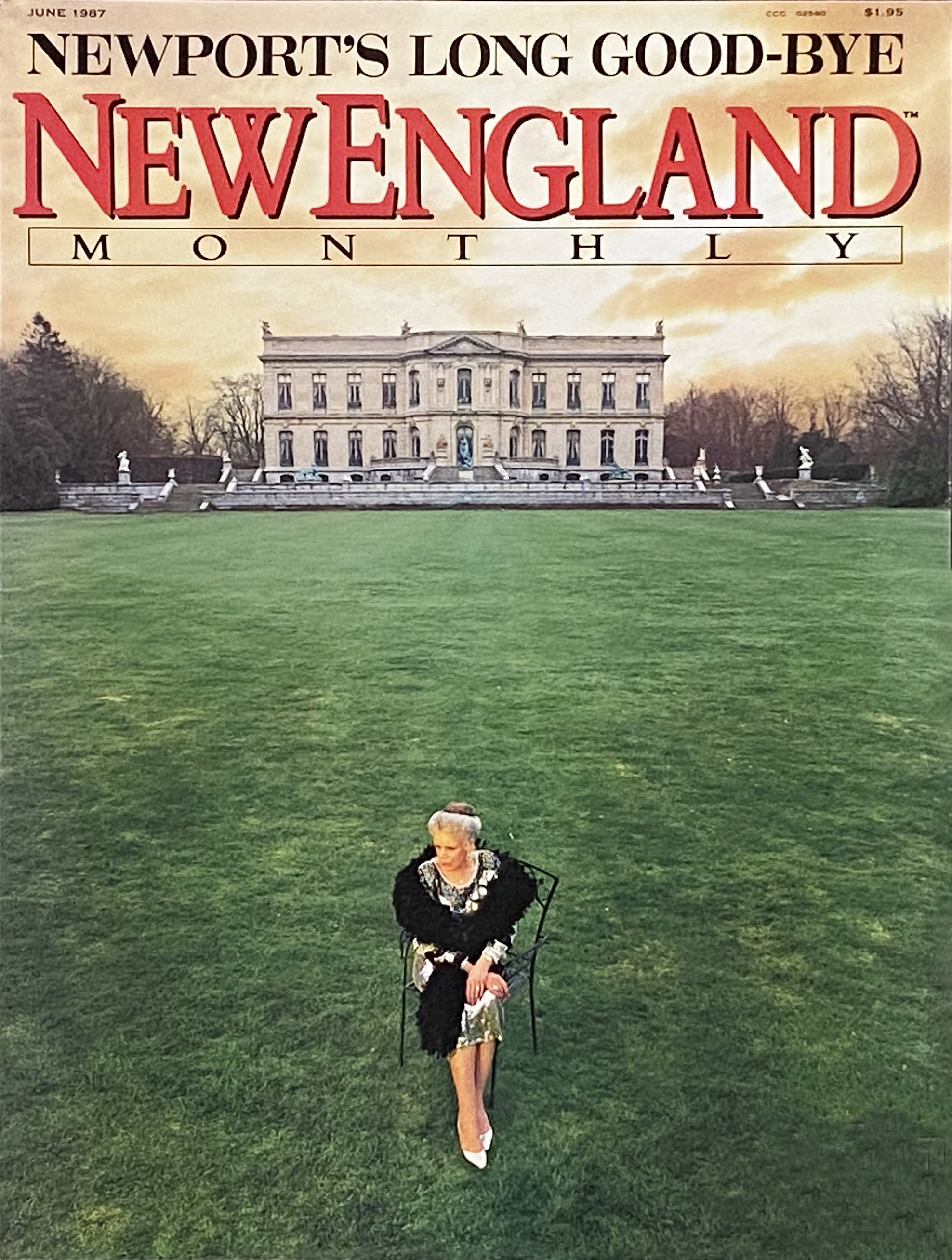

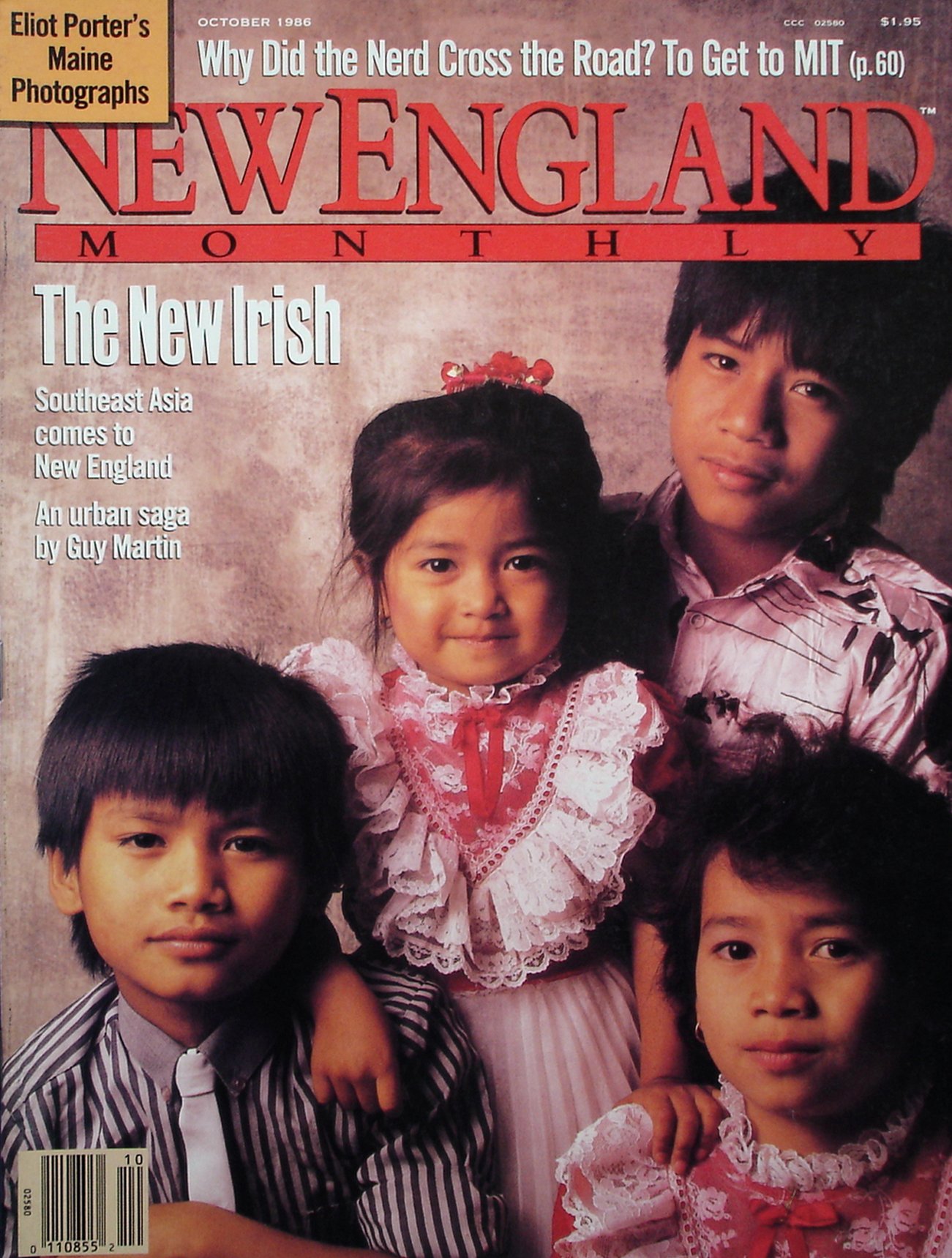

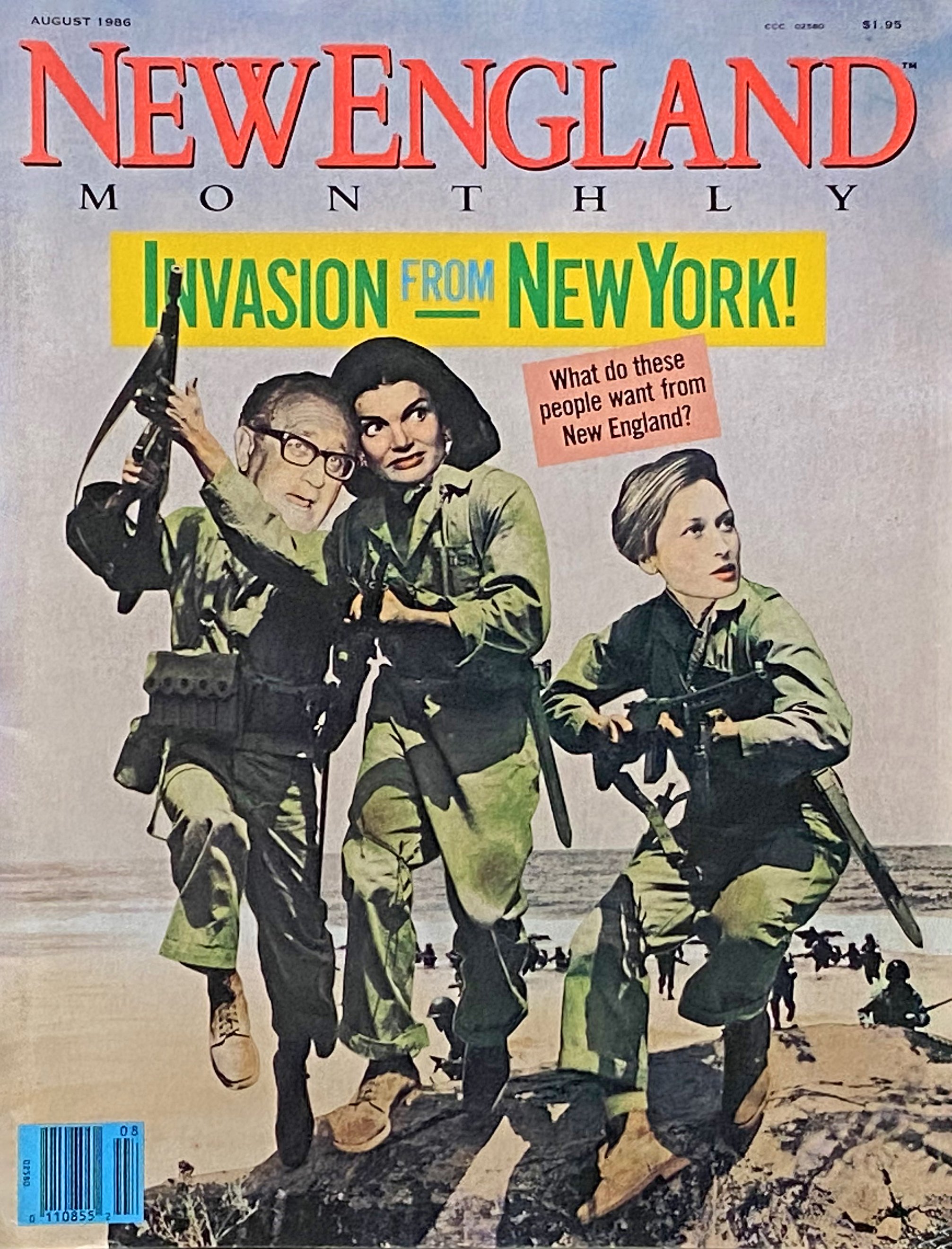

George Gendron: That’s very true. Now, one thing that your life as a book editor did was it took you down to Texas Monthly. You were working with them on helping them build out a Texas Monthly book line, if I’m right. And that connection ended up with you eventually launching a brilliant magazine, New England Monthly, which doesn’t exist any longer unfortunately. Tell us that story. You’re down there [in Texas]. Where the heck does the idea for New England Monthly come from when you’re down in Austin, Texas?

Dan Okrent: Well, you just remove the five letters of TEXAS and you put in the 10 letters of NEW ENGLAND and, BOOM, it’s done! My business partner [Bob Nylen], with whom I started New England Monthly—and we ran it jointly for five-and-a-half of its seven years—had been the advertising director and associate publisher of Texas Monthly. He had a fight with the boss. He quit.

He and I always got along together. He said, I said, somebody said, “Let’s put on a show. Let’s start a business together.” And we had a bunch of flaky ideas. And then Bob Nylen finally said, “Look, the business I know is magazine publishing. You know enough as an editor and as a writer for magazines, I’m sure you can learn the editorial side of it. Let’s start a magazine.”

And, basically, on the same principle, if not formula, as Texas Monthly. Intense, focused coverage on one small area. We were not interested if it was happening somewhere else. And in fact, what Texas Monthly did in its early days, and that we did as well, if you lived outside of New England and you wanted to subscribe, you had to pay twice as much as somebody who lived in New England.

George Gendron: I didn’t know that. Is that right?

Dan Okrent: Yes. And there were two reasons for it. Three. One was sheer exclusivity, you know, “join the club.” The second one is that we have this one subject and we want to deal with it in a way that connects to the lives that people in New England live. And third, it was a great advertising pitch. Because the advertisers who were buying regionally in the national magazines already could now have something that was specific to New England that they could put money in and they weren’t wasting dollars and overlapping with the Chicago market, or wherever else it might be.

So for local advertisers it worked quite well. And for national advertisers it was great because, for instance, taking the auto companies, Ford was always a loser in New England and Chrysler was especially strong in the northeast, generally, Northeast and New England. Chrysler became our biggest advertiser in the automobile industry. They had this presence in New England and they wanted to keep on pushing on it. Anyway, it worked until the New England economy crashed and then it didn’t work.

George Gendron: So, I love the expression you use. You and Nylen sit down and you don’t say, “Well, how about if we start a magazine?” You say, “Let’s put on a show.”

Dan Okrent: Well, it’s sort of like those publishers you talked about who talked about money before talking about the concept, not “what are we doing here?”

George Gendron: Yeah. But I want to go back and just make sure I got this straight. You just said that Bob says to you, “You have no magazine experience whatsoever. You’ve never worked in a magazine, but that’s okay. You can learn that on your job,” basically.

Dan Okrent: Well, yes, but—Texas Monthly had one stockholder, the publisher, Mike Levy—but there was an executive committee that was like a board of directors. And I was on that. So I would go to these meetings once a month when I was in Austin. And you learn a lot sitting there listening to the circulation director argue with the advertising director and the production manager saying why we can’t do it.

And then the editorial side, as I said, I had written for magazines. I was pretty well established. I was writing for Sports Illustrated and Esquire primarily. I had all the assignments I needed. I did some other stuff. I did a piece for Inc., for Inc. Life. There’s a great story in that one. So I wasn’t a total blank slate.

So when he said, “You can learn,” you know, I had already made it past the fourth grade. So I didn’t have to start all over in primary school.

George Gendron: You said, at one point to me, you thought maybe your biggest strength was as a fundraiser.

Dan Okrent: It was amazing that we were able to raise $3.5 million in 1983. That would be, in today’s money, something like $20 million. This startup magazine that had an outside circulation goal of 350,000, and was only going to circulate in six states. So I must have been really good at it.

The first investors were people who had had the chance to invest in Texas Monthly and had passed on it. Now they say, “Oh, here are these two guys coming out of Texas Monthly and they know the formula. They’ll do it in New England.” Well, they were wrong and so were we.

George Gendron: But anybody wanting to raise money might want to tuck that away in the back of their minds about how do you search for investors?

Dan Okrent: Well, there’s another way to search for investors, and I learned this in my theater career, as brief as it was, tell people you don’t need investors and they come pounding on your door. “Please let me in! Let me in!” And that happened with New England Monthly to a degree, too.

“There’s another lesson there that I never took advantage of which is: if the boss has a title that doesn’t sound like a boss, nobody bothers him.”

George Gendron: Yeah. If you listen to CEOs at a conference, at the bar at six o’clock at night, they’ll all talk about how the best way to get a banker is just mention, casually, you really don’t need a loan. So you’re running New England Monthly. You launch it, it’s a big deal. It becomes a really, really big deal. Who did you turn to for advice?

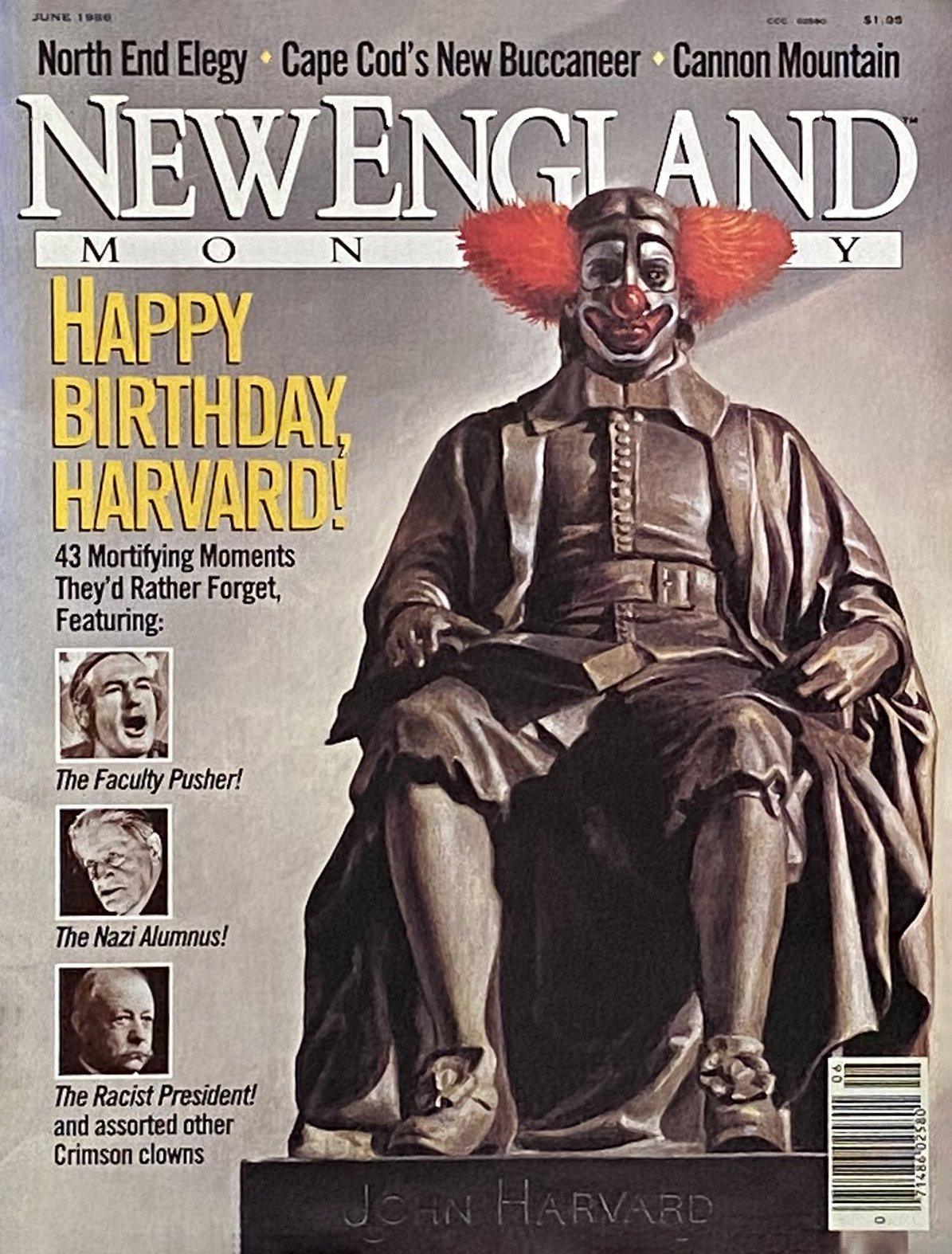

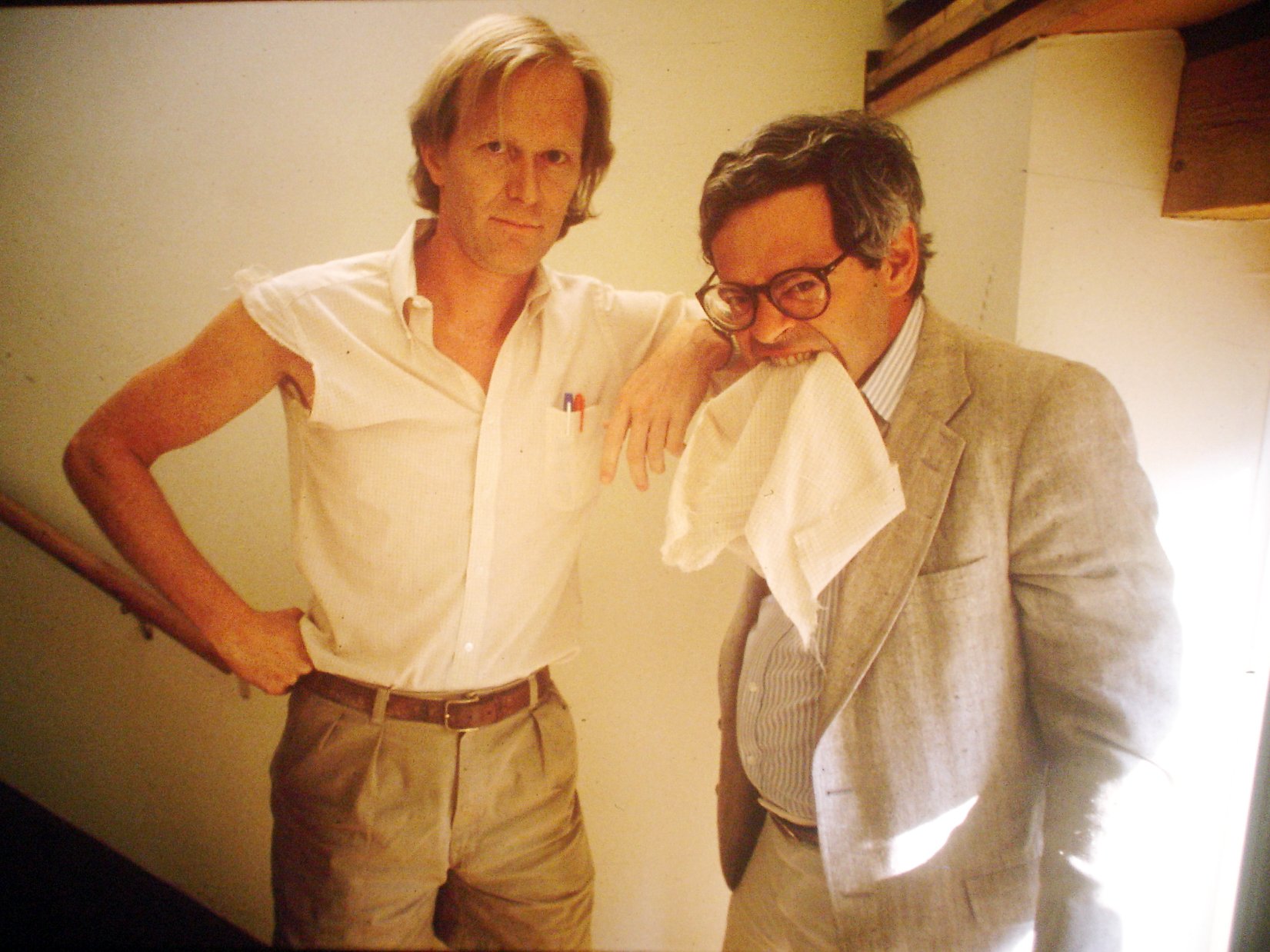

Dan Okrent: There are three good friends that I turned to for advice, not just in the very early days. One was Jim Gaines, who had just been made the editor of People magazine. A college friend. We’ve known each other forever. His daughter is my goddaughter. Another was Greg Curtis, who had become the editor of Texas Monthly, and with whom I had a very, very good close friendship from the beginning of my time down there. And third was Lee Eisenberg, who’s my son’s godfather, who was the editor of Esquire at the time.

And they would read it and let me have it about, you know, “Why’d you do this? Why’d you do that? What a stupid thing.” And I I loved that. That was great. It was a trial by fire. I mean, I look at my first six issues. “What? This guy was editing a magazine?” I didn’t know. It’s kind of ridiculous.

George Gendron: Yeah. But, you know, on the plus side, I think what’s really important in the first issue or the first several issues is you really nail the mission, tone, sensibility of the magazine. I think you guys did that. There might have been things you could have improved with regard to execution. But you converted a lot of people very early on, and I’m talking about industry people who were very skeptical in the first place. Especially when they heard New England Monthly, they started to think about Yankee magazine.

Dan Okrent: Exactly. We said, “Well, you know, Yankee magazine’s great.” Two-thirds of the subscribers don’t even live in New England. They have this imagined, quaint view. And it’s a quaint magazine. And remember Jud Hale, who was the editor, got really angry about it. He said, “We ain’t quaint!”

That was his speech whenever anybody brought up New England Monthly. “We ain’t quaint!” Sounded like it was from Texas, actually. And there was also that we were dismissed as two guys from Texas. “What do they know about New England?” “Well, I had been living in New England for, at that point, six years. Bob was born and raised in New England. It was hardly foreign territory. But in terms of sensibility, and thank you very much for those kind words about it, there were a few things that we did from the beginning that were right.

Part of this thing about not having subscribers outside of the area is we had an intimate language with our readers. You know, when you said Narragansett Bay, you didn’t have to explain where Narragansett Bay was. Or when you’re talking about, uh, First Boston. Or Shawmut was your bank. Or you’re writing an article about Shawmut. Okay, I know who Shawmut is. They’re the biggest bank in two of the three lower [New England] states.

So there was that. Secondarily, and this was something that I think I learned from Lee more than anybody, and this is one that you knew very clearly in your career: don’t publish anything that isn’t interesting to you.

And that was certainly evident in your work, George. And I’d like to think it was evident in ours. And we did not write down to anybody. We assumed that the readers were around the same dinner table that we were, and we were having a great conversation.

George Gendron: That last characteristic is the one that I associate with my impressions of the first issues of your magazine, and that’s captivating.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. It’s not all that common.

Scenes from a magazine: New England Monthly

George Gendron: Yeah. Hard to achieve.

Dan Okrent: It’s not hard to achieve if you don’t know what you’re doing.

George Gendron: Actually, you know what? That’s true. Well, for me, I picked up this habit of never publishing anything I wasn’t genuinely curious about in the first place. And wasn’t avid to read once it was actually handed to me in manuscript form at New York magazine and then at Boston magazine where, you know, you are your own best market.

At Inc it was a little bit different because we were writing for people who owned businesses and entrepreneurs. And none of us were business people. And so there was a little bit more there, trying to cultivate a sense of audience. But even then, we thought of it less as a magazine about business or management and much more as a magazine about creation. About taking an idea and turning it into something tangible, which was something we were all passionate about.

Dan Okrent: Right. Of course. And it worked really well.

George Gendron: It did work. And people responded to it. So I want to talk about talent now. So you’re up in New England, the magazine is out in western Massachusetts, right? There’s not a big pool of talent out there. Now I know you were using writers from around the region who didn’t necessarily live in Western Mass., but you assembled a really talented crew. People like Hans Teensma will tell you that they still are benefiting from some of the talent that you attracted.

Dan Okrent: When I was developing New England Monthly, I was down there and this guy came in. He had been art director of Rocky Mountain Magazine, which I admired, which had folded. And he was one of three finalists to be the art director of Texas Monthly. And Greg, who was the editor, had everybody in the management committee interview him. And I just think, I remember saying, “I hope Greg doesn’t hire him. I hope Greg doesn’t hire him.” And Greg did not hire him. And I did. It was really perfect. But, in terms of talent, I think that people liked the idea of working for a magazine that didn’t talk down to its readers.

I wouldn’t begin to compare New England Monthly to The New Yorker. But in that sense our writers were as sophisticated, as literate, as ironic. And writers kind of hunger for the chance to do that kind of work. And we didn’t have a lot of staff writers. I think we had three at the most. Among them were people who came to the door and said, “I want to work here.” Jonathan Harr, Darcy Frey, a variety of others.

George Gendron: Big talent.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. But this is when they weren’t yet big talent. But at the same time, we were commissioning pieces from Ward Just, and from Donald Hall, and—this was another secret tip that I have for people who are starting publications who can’t afford to pay what the competition is paying: pay them immediately.

And as a freelance writer, I learned that one. Here’s a nice assignment from Esquire. My check comes three months later? Well, here’s a nice assignment from New England Monthly, and it’s only half of what I’d be getting from Esquire, but I got the check the next day.

George Gendron: That’s only the second time in my entire career I’ve ever heard an organization treating freelancers that way. The other is a magnificent branding boutique called Mechanica, and it’s just phenomenal. It’s a small group, maybe 20 people, that does the work of an organization three or four times as large because they have a very carefully-curated network of contributors that they treat as well as, or better than, staff. And they pay them the day the work is accepted. Period. End of story. And boy, people don’t understand the loyalty that creates.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. And the freelancer’s life has always been pretty rotten. I have a feeling it’s a lot more rotten now than it’s ever been. And the very idea of living on a float from your contributors—“You write the piece today and I put the money in my bank for three months, collect a little interest or whatever”—that’s kind of disgusting.

Time Inc. (1997-2001)

“Detroit’s disaster has long been a slow unwinding that seemed to remove it from the rest of the country. Even the death rattle that in the past year emanated from its signature industry brought more attention to the auto executives than to the people of the city, who had for so long been victimized by their dreadful decision-making.”

In 2009, Time Inc. bought a house in Detroit—once the most prosperous manufacturing city in the nation that had been brought to its knees by a combination of crime, economic downturn, and corrupt leadership—to create “Project Detroit,” a year-long effort that sent some of the world’s top journalists to the beleaguered city. Okrent’s piece for Time kicked off the series. He was chosen to write it because he had grown up there.

George Gendron: It really is. And it’s unfortunate that some really reputable places still do that. I’m not going to name them, but a major newspaper—I have a former student who’s a brilliant and very well-known photographer who did a project for this newspaper and it took her 12 months to get paid.

Dan Okrent: Well, I had a front page review, in the book review of a newspaper I will not name, in August and I still haven’t gotten paid.

George Gendron: So that practice is alive and well.

Dan Okrent: Yep. Yep.

George Gendron: Man! So anybody out there listening, you want to talk about how, as we increasingly work with this unbelievably rich pool of soloists and freelancers, pay them. Pay them on time. Pay them before they ever even have to ask for the check.

Dan Okrent: Right. And for those freelancers in the talent pool, I would say when they offer you $10,000 for the job, say, “I’ll do it for eight if you pay me the day that it’s complete.”

George Gendron: That’s great advice, man. That’s great advice. Going back to the writers that you had, I have to confess my favorite regular contributor was your “gardening columnist,” the novelist, Annie Proulx.

The New England Monthly staff at one of Okrent’s legendary “Whale Meetings.”

Dan Okrent: Oh, that’s so great that you remember that. I take great pride in that. Annie Proulx was living in Vermont. She had written here and there for small magazines. She was trying to write fiction. She became our gardening columnist, and this was years before she became a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist. And we had, you know, Michael Kimmelman, who is the architecture critic of the Times now and had been the art critic for many, many years. He was the architecture critic of New England Monthly. That was one of his very first gigs. And there are many, many more people who started their careers there. And I’m very proud of that.

George Gendron: What’s equally extraordinary about what you just said is the fact that New England Monthly, back in the ’80s had an architecture critic!

Dan Okrent: Well, he wasn’t full-time.

George Gendron: I know what you mean, but still.

Dan Okrent: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s always a subject I’m interested in.

George Gendron: So everybody who has ever worked intensely with you on the Monthly says, “Oh, you know, when you have a conversation with Dan, you got to ask him about the “whale meetings.”

Dan Okrent: Well, the Whale Inn in Cummington, Massachusetts, was kind of a—I hope they’re not listening—kind of a collapsing country inn with a liquor license. So, uh, the editorial staff—at times had been just the senior editorial staff, but eventually the whole editorial staff—once a month we would go have the “whale meeting,” which was to talk about, you know, “What should we be doing?” “What are we doing right?” “Who are some writers we haven’t found?”

It was just an opportunity, away from the office, to brainstorm for three hours. And to get a little smashed. Those of us who were of that ilk. And I think good things came out of it. But the lesson, if there is a lesson, was talking to your whole staff. That’s really, really important. Not just talking to lieutenants.

“Whatever nice things that people might have said about working there with me, I was pretty impossible. And I got more and more impossible, more authoritarian, probably grumpier. So it was time for me to get out.”

George Gendron: That’s what everybody mentions. Just the idea that this was not hierarchical. It was not about authority, it was about influence. And alcohol.

Dan Okrent: Yeah. But it was hierarchical. I mean, you know this well, and I think that any editor of a magazine or newspaper, top editor, knows this. It’s “Everybody’s got their say and only one person has a decision.” And I’ve said this to writers who’ve had pieces killed, turned down by magazines. “Well, he’s totally wrong about this.” I said, “No, you don’t understand. The editor in chief is right even when he’s wrong.”

George Gendron: Yeah, yeah, of course. Any questions? No, I’m just getting at the idea that I remember I was interviewing somebody from Forbes, at one point, for a job. And they were telling me—the story might be apocryphal, but it’s a good story, and I think the spirit of it is accurate—that they went in and they were being reviewed and they were offered a promotion and a raise, or an opportunity to be permitted to participate in story meetings.

Dan Okrent: Right, exactly. The other way to do that, the devious way to do that, is titles. You want to raise or you want to be called senior editor?

George Gendron: I got that at New York magazine. I always ended up taking the money. So I ended up with a really great job there. And recently somebody said to me, “But your title was, like, editorial assistant.” I know, but I needed to live, man. I needed to pay my rent in New York.

Dan Okrent: There’s another lesson there that I never took advantage of which is: if the boss has a title that doesn’t sound like a boss, nobody bothers him. And I learned this from a company that I think you wrote about Vermont Castings, in Randolph, Vermont, which made wood stoves during a time when wood stoves were very hot, obviously, in the market. And the guy who ran it was a man named Duncan Syme.

And I went to have a meeting with him once because we were going to be publishing something about it. And I get to their building and there’s the office directory. And near the bottom, the title was something like “Marketing Assistant Duncan Syme.” Nobody bothered him. He did not have people coming to ask for jobs, or asking for contributions to the local PTA, or anything you want. He just did his job under the guise of a non-title.

George Gendron: Man, that tells you something about that man’s ego, right?

Dan Okrent: Yeah, it does.

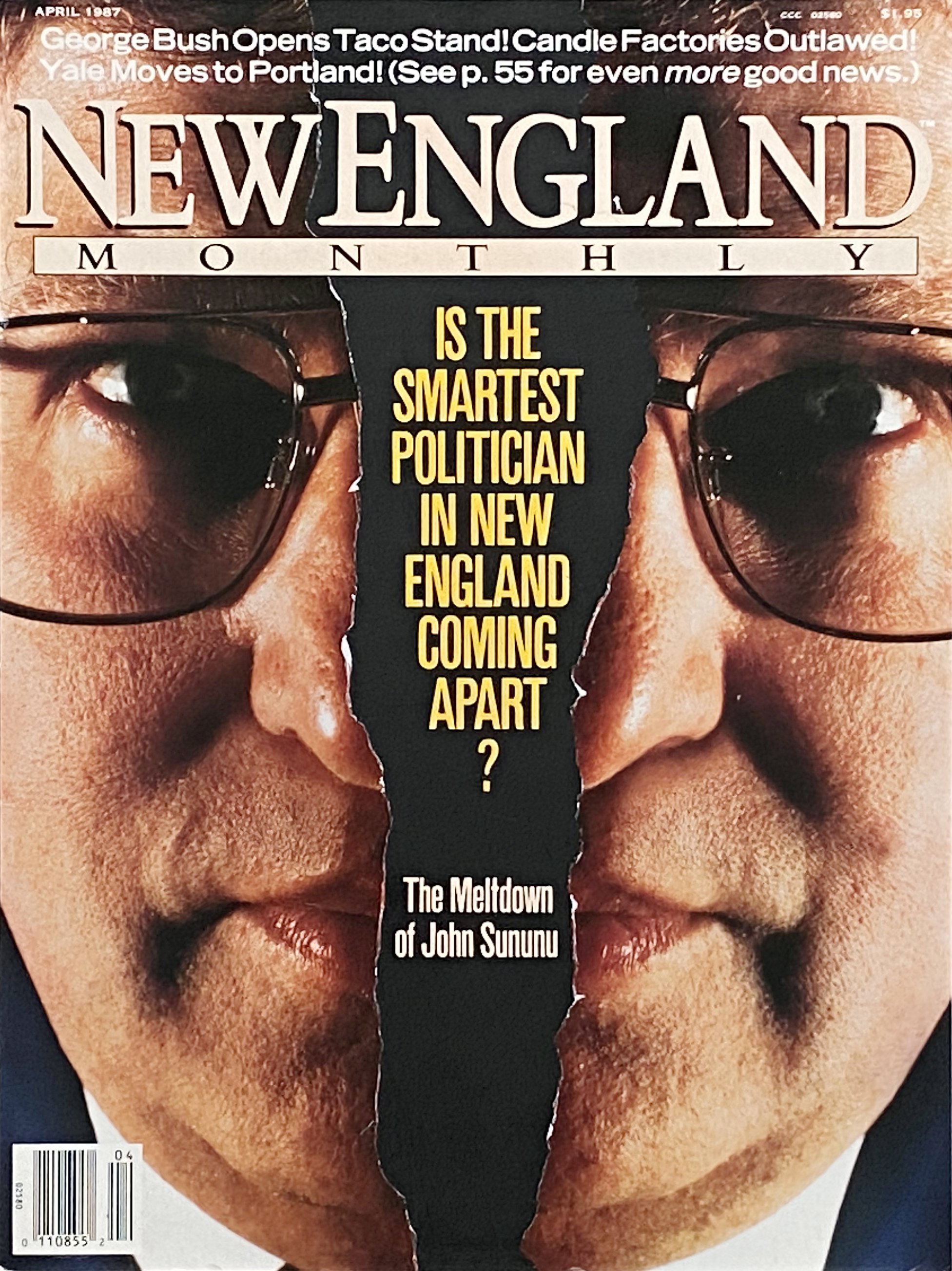

George Gendron: And about how he valued this time. So here you are, you’re running, you and Nylen are running this very hot magazine, and, I don’t know, five-and-a-half years into it or something, you quit. You quit the magazine you yourself launched. Why’d you leave?

Dan Okrent: Well, we fell on economic hard times. We never got to pure profitability, but we were trending in the right direction. And then there was a big bump in the New England economy. And we had, by the time we were done, we had milked our investors for $7 million. People who put money back then into magazines never expected that the initial check was the only check. Only my really tight, skinflint brother-in-law was upset by it. He didn’t want to put any more money, “I put my money in!”

Anyway, we sold the magazine to a Canadian company called Telemedia. And I just, I had done five-and-a-half years of working really, really, really hard. The reward that I was hoping for was not going to come, because we sold it for a dollar, basically, and we sold it for the debt. I had never had a boss and now I had a boss and it just felt like it was time to go, for me. That’s all.

And I had some other things I was interested in doing. And it was absolutely the right decision. Absolutely, for me. And I think for the magazine as well. People, whatever nice things that people might have said about working there with me, I was pretty impossible. And I got more and more impossible, more authoritarian, probably grumpier. So it was time for me to get out.

George Gendron: I understand that. I’m not sure I’ve ever told this story publicly, but so we sell Inc. to Bertelsmann, the German media company—people might be more familiar here in the magazine industry with Grüner + Jahr, which was their North American magazine publishing arm. And I get on the plane to fly to Germany for, I guess, what was the tradition, which is you get up in front of the annual management meeting of all the top people and you explain to them what it is that they’ve acquired.

So I’m sitting on the plane and there’s this German executive sitting next to me, and we start talking and he says, “What are you doing over there?” And I explained it. And I say to him, “Well, I run the creative team at Inc. Magazine, and we sold it to Bertlesman. And I’m heading over to meet with their management team. And he said, “Oh, I’m so sorry.”

I said, “Why are you sorry?” He said, “Because you’re going to spend the future years of your life measuring the irrelevant with absolute precision.”

Dan Okrent: That is so great. I’m stealing that.

George Gendron: That was the quote of the year. Six months later, boy, was that true? Oh my God.

Dan Okrent: How long did you stay with the magazine after the Bertlesman deal?

George Gendron: I don’t know. Maybe a year?

Dan Okrent: Well, so, you were feeling a little bit of the same thing that I felt after we sold to Telemedia, except you had more money in your pocket. That’s all.

The New York Times (2003–2005)

George Gendron: Yeah. That’s true. So you told me that you didn’t really realize how little, from one perspective, how little you knew about magazine publishing operations until years later when you’re back with Gaines again at Life magazine.

Dan Okrent: Oh yeah. Just the way that they did things. I said, “Oh! Before you do a cover, you do 10 covers, and you put ’em on the wall, and you see how people react. And you have a layout room where every spread is looked at and should this be moved here and should that be moved there!”

And just ...and the process and the speed! Even though Life was a monthly then. They would go up to the day before—they would assign articles halfway around the globe two days before closing because the company was built on that weekly magazine metabolism. And it was all really surprising.

And then also I learned, because this is what everybody who worked at Time Inc. in the glory years learned. You can spend all the money you want to put out a magazine! I had been pinching pennies for six years, and when I took over as the editor of Life, two years after I began with Gaines on a part-time basis.

I couldn’t believe how, “Oh, you know, you need an aircraft carrier in the Arabian Sea? Oh, sure, we’ll get you one.” It was almost that. The company’s resources were deep and vast. And that was kind of exciting to be able to have. I never really learned how to use it because my old moves of pinching pennies—they were embedded in me. I didn’t know how to spend as much as I should have spent.

George Gendron: I was talking to a friend of mine, who was one of the first female National Geographic photographers ages ago, and she confirmed a story that I had heard before, but I had never believed. And that was, she was shooting, I think it was in the Congo at one point, and she had to get from point A to point B, and there were no flights. And she went to rent a Jeep and there were no Jeeps available.

And so she was talking to New York and they said, “Well, go buy one. Go buy whatever you can find, four wheel drive, go buy it, travel there, and when you’re finished sell it.”

Dan Okrent: The great Time art critic, Robert Hughes—the greatest art critic of the last quarter of the 20th century—he once was doing a story in France. It started in Paris, and he rented a motorcycle. And he took the motorcycle down to Provence where much of the work was being done. Gets back to the office a couple weeks later and the cost-control people come to him and say, “We have this bill that says you didn’t return your motorcycle. And they say that we’re liable for the cost of the motorcycle.” And he said, “Yeah, I didn’t return the motorcycle. I didn’t need it anymore.”

George Gendron: Well, this photographer bought a brand new Range Rover Defender. But she sold it back to the dealer.

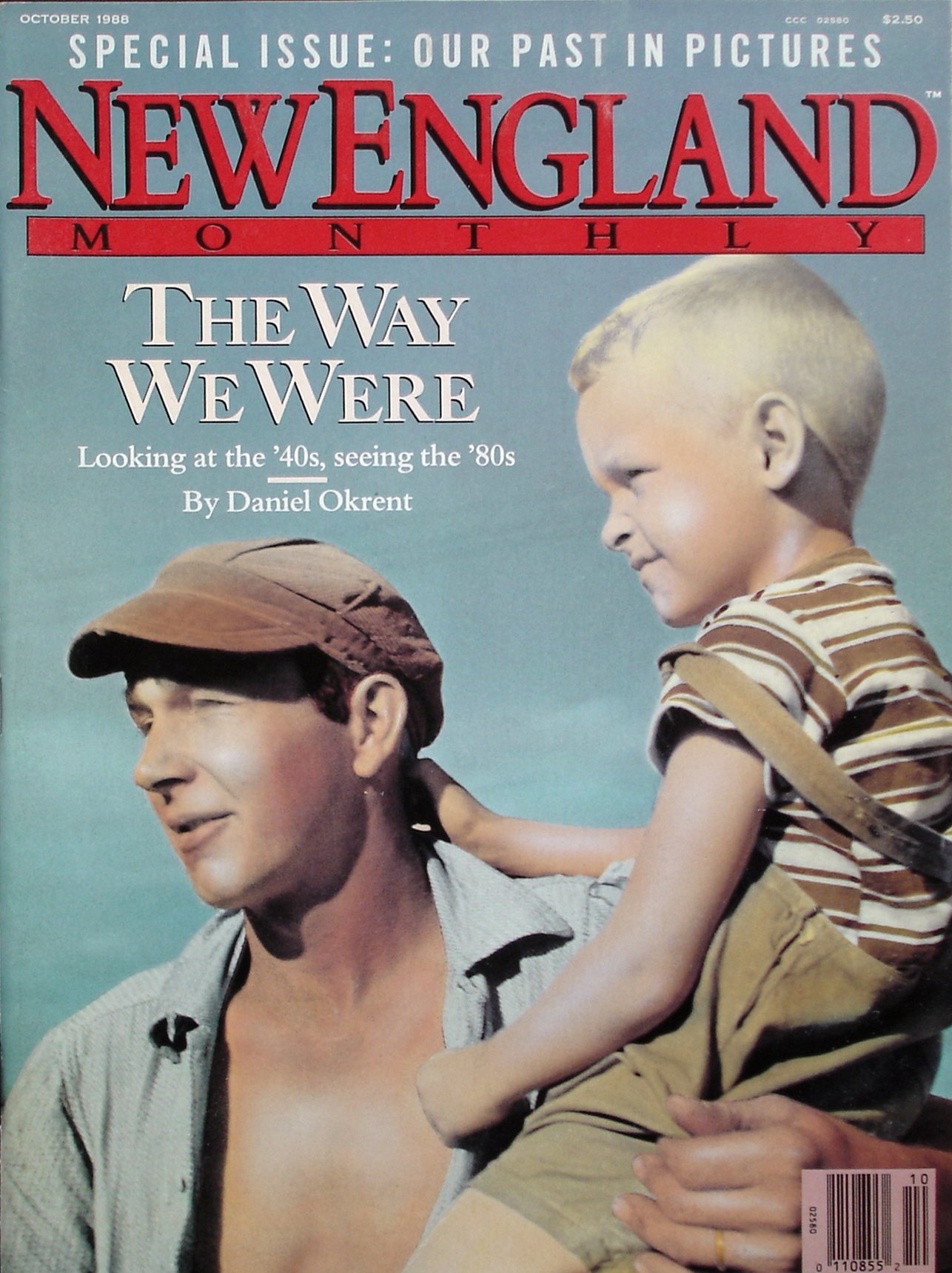

So I have to ask you this question, as we come to the conclusion of the New England Monthly saga. You’ve written a bunch of books, and I want to talk about one in particular in a second that’s my favorite, Last Call. And I’m really curious. What was more thrilling for you: the day when you got the first hard copy of Last Call in your hands from the publisher or the day when you got the first issue of New England Monthly in your hands from the printer?

Dan Okrent: I’d have to say it was New England Monthly. Partly because Last Call was my fourth book. It wasn’t totally new to me. But, but, but, but, oh, yeah. I remember where I was. And I remember it came by messenger—remember messengers?—and I hefted it, and I smelled it, and I made sure my name was spelled right. Which is not as ridiculous as you might think!

My friend Steve Harrigan, writing under the name Stephen Harrigan, is a very accomplished novelist. His first novel was published by Knopf in the ’80s. And Avon bought the paperback rights and he got the box of the first 20 copies of the paperback at his home in Austin. Opened it up, it looked great. The title page said Stephen “Harrington.” Not “Harrigan.” They got the fucking author’s name wrong! They got the author’s name wrong. Yeah, it just, it’s really incredible.

George Gendron: Okay, so I’m going to ask you a couple of relatively quick questions. Were there any dream jobs in publishing that you really, really wanted that you never got?

Dan Okrent: Yes. I think that one was the editor of Sports Illustrated. And I was put through a public trial. Norm Pearlstine, the editor-in-chief, had this ridiculous idea that he would have three people compete publicly and each one would edit the magazine for six weeks.

Well, the third candidate dropped out immediately because she knew this was ridiculous. But I had been at Life for four years. I was getting the itch. I had read Sports Illustrated since my early boyhood. And so I was put in a competition against Bill Colson, who had been selected by the retiring editor-in-chief. He was the inside guy who was going to get it.

And so he put out a magazine for 12 weeks, and then I put out a magazine for 12 weeks. And Norm picked Bill. I could give you all sorts of good reasons for why he made that pick. But the whole process was kind of humiliating. Losing in public is not pleasant.

But, I rebounded soon enough. And, actually, that was around the time I said, “I never want another job.” And I never did have another job. I spent my last three years at Time Inc. as an editor-at-large, which is the best non-job in the world. I worked for all the magazines only when they needed me. And I got paid like management. And I took early retirement to go write books and that’s mostly what I’ve done ever since.

George Gendron: Okay. I’m going to completely shift gears now. These are going to be non sequiturs. I said a minute ago, my favorite book of yours by far—and I know a lot of them have been very, very well received—was Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. And I’m not going to spend a lot of time flattering you about the book. Others have done that. But, one thing that I find remarkable...

Dan Okrent: No! Don’t, don’t stop, don’t stop! Sorry.

George Gendron: ...one thing I find remarkable about it is that it’s such a vivid reminder of the poverty of the way in which we, here in the US, are taught history. Where we memorize dates, and we are fundamentally historical illiterates in this country about our own history. And what that book does so magnificently is it uses narrative to bring to life how events came to pass, how complicated things really are, that we always had been taught, or at least suggested, were unbelievably simple and one dimensional.

Dan Okrent: Right, right. Yeah. History is complex. It works in strange ways. But the point you make about narrative—this is a very conscious choice that I learned as a magazine writer and editor. Tell a story. And if you don’t have a story to tell, you’re writing about a topic, not a story. Somebody comes to me and said, “I want to write an article about the timber industry in Northern Maine falling apart.” And I said, “Well, that’s the topic. What’s the story?” And my dear, late friend Dick Todd, who succeeded me as editor of New England Monthly, he put in my skull words that are forever there: chronology is your friend. If you tell the story the way it unreels, you’re in great shape.

George Gendron: Well, I love that book.

Dan Okrent: Thank you.

George Gendron: So thank you. Very quickly, as if you haven’t already had a varied career that we’ve been chronicling here, you also launched a Broadway play at the West Side Theater called Old Jews Tell Jokes?

Dan Okrent: Old Jews Telling Jokes. I have to say, it was Off Broadway. But it was at the Westside Theater. Which is very close to Broadway. But it’s a much smaller house. Yeah. That was just a hoot. That began with a website called Old Jews Telling Jokes, which I discovered because I tell jokes. And people, whoever just thought, “Oh, Dan’ll like this.” And what it was was old Jews, one at a time, telling jokes. And I volunteered. And I wasn’t quite old enough. I had to wait six months, because they didn’t want me until I was 60.

I told a joke. I told three jokes. It was a blast. And my buddy, Peter Gethers, said, “Maybe this would be a nightclub act or something.” That was in 2009. And then we went through such extraordinary—and neither of us had any experience in the theater. None. Zero. We went to the theater a lot, but we didn’t have any experience.

The Story of Old Jews Telling Jokes

George Gendron: Here we go again. A little bit of naïvete.

Dan Okrent: Yeah, absolutely. And then there we were in 2012. We opened, we ran from 521 performances. We raised $1.2 million and we had a show. And that was one where I did say to people who said, “How can I invest?” I said, “You can’t.” “Please, please!” And then the more they said, the more they said, “Please!”, the better our terms got, and the worse theirs got.

George Gendron: So you and Bob Nylen have this seminal conversation about New England Monthly and say, “Let’s put on a show.” And in this case you sit down and you actually put on a show.

Dan Okrent: That’s true. We actually put on a show. We were a success. There’s a road company that’s still bopping around here and there. And Peter and I then had a couple of other ideas we tried to develop. We thought we were becoming theater producers. And we realized—we woke up one morning, said, “We really got lucky. Let’s not mess it up.”

And I should mention that Peter is an editor at Random House, was head of Random House’s television and film production studio, has written eight thrillers and four non-fiction books, wrote many episodes of Kate & Allie. He’s done everything. A much more varied career than I, but we were a perfect match because we were both willing to try something new.

George Gendron: Well, in addition to being in books, launching a magazine, launching an Off-Broadway show, and among many other accomplishments, according to people who are really, really knowledgeable about fantasy sports, you really are the godfather of fantasy sports. And so how rich did it make you?

Dan Okrent: Oh, fabulously wealthy. That’s why I’m not working now. It has nothing to do with the fact that I’m 75 and nobody will hire me. No. It, it, you know, we did try early on to make some money marketing the name Rotisserie League, which was the original fantasy league that we started in 1980, baseball Fantasy League.

But the rules were so simple, and somebody came up with the term “fantasy baseball" instead of rotisserie baseball. We had protected the trademark of rotisserie, but who needed it any longer. And this was all, I should say, that in our not making any meaningful money from it, this was all way before the internet. We started in 1980.

By the time the internet was picking up in the early ’90s, the big boys—ESPN, Sports Illustrated, CBS—were all moving into doing fantasy sports online. And that’s where it really exploded. But, I’ll, I’ll take credit, if not a Ferrari, for having started it.

George Gendron: Which would you rather credit or a Ferrari?

Dan Okrent: Oh, God. I’ve gotten the credit. Don’t tempt me.

Ken Burns’ Baseball

Dan Okrent’s latest book, The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America, tells the chilling story of how anti-immigration activists of the early twentieth century—most of them well-born, many of them progressives—used the bogus science of eugenics to justify closing the immigration door in 1924. Buy it wherever books are sold. Follow Okrent on Twitter, Instagram, or visit his website.