A Little Romance

A conversation with photo editor and author Kathy Ryan (The New York Times Magazine, Office Romance).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF ISSUES MAGAZINE SHOP

Photograph by Philip Montgomery

Kathy Ryan’s career journey began in Bound Brook, New Jersey, at St Joseph’s Catholic School. Her third grade teacher, Sister Mary William, had a thing for great works of art. And, as it turns out, so did Ryan.

“I got it. I so got it. Looking at the pictures and just understanding. It was like, ‘Wow, I get it.’”

That understanding of the power of the visual led Ryan to a focus on art in college—on lithography and printmaking. But the solemn life of an artist wasn’t for her. She hated being alone all day. She loved working with people. She wanted to be part of a team.

Kathy Ryan was made for magazines.

After starting her career at Sygma, the renowned French photo agency, Ryan was hired away by The New York Times Magazine in 1985. She had found her team.

In her tenure at the Times, she has collaborated with all the bold-face names: Jake Silverstein and Gail Bichler (the current editor-in-chief and creative director) as well as Adam Moss, Rem Duplessis, Janet Froelich, Peter Howe, Diana Laguardia, Gerald Marzorati, Ken Kendrick, and Jack Rosenthal. And between and among them they’ve won all the awards—and created one of the world’s truly great magazines.

Recently, Ryan’s work at the Times took a new turn. Inspired by her collaborations with the most gifted photographers in the business, Ryan started making a few pictures of her own.

She had always been mesmerized by the way the light hit the Renzo Piano-designed Times headquarters. But on this particularly sunny morning, Ryan pulled out her phone and snapped a picture. Then she took another. And another. She started seeing pictures everywhere. Portraits, abstracts—whatever caught her eye. Encouraged by friends and colleagues, she posted them on Instagram with the hashtag #officeromance.

After a career of looking at pictures, she is now making them. And that led to her glorious book, Office Romance, published by Aperture in 2014.

We talked to Ryan about her passion for the art of work, about the thrill of discovering incredible talent in unexpected places, and about the responsibility that comes with sending photojournalists into harm’s way.

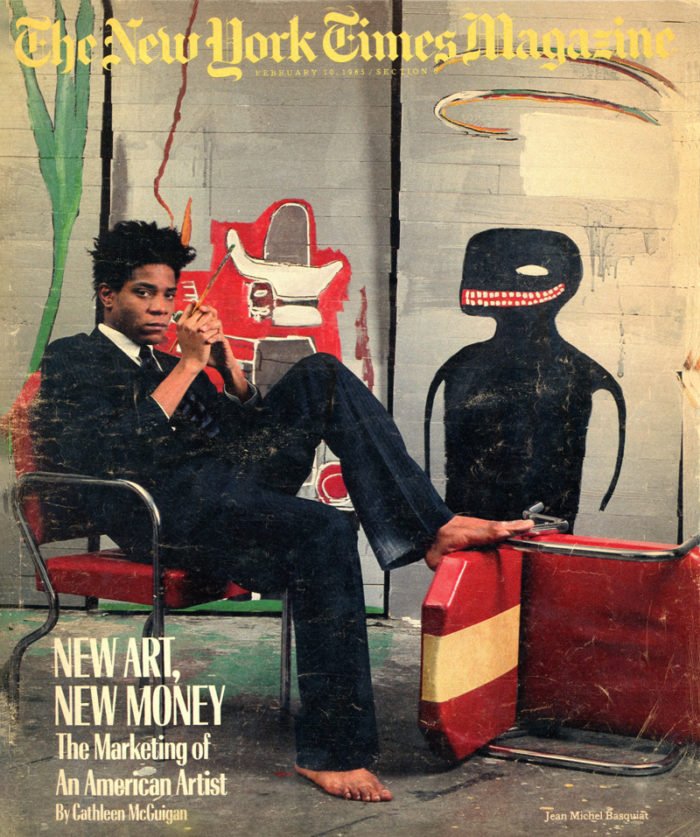

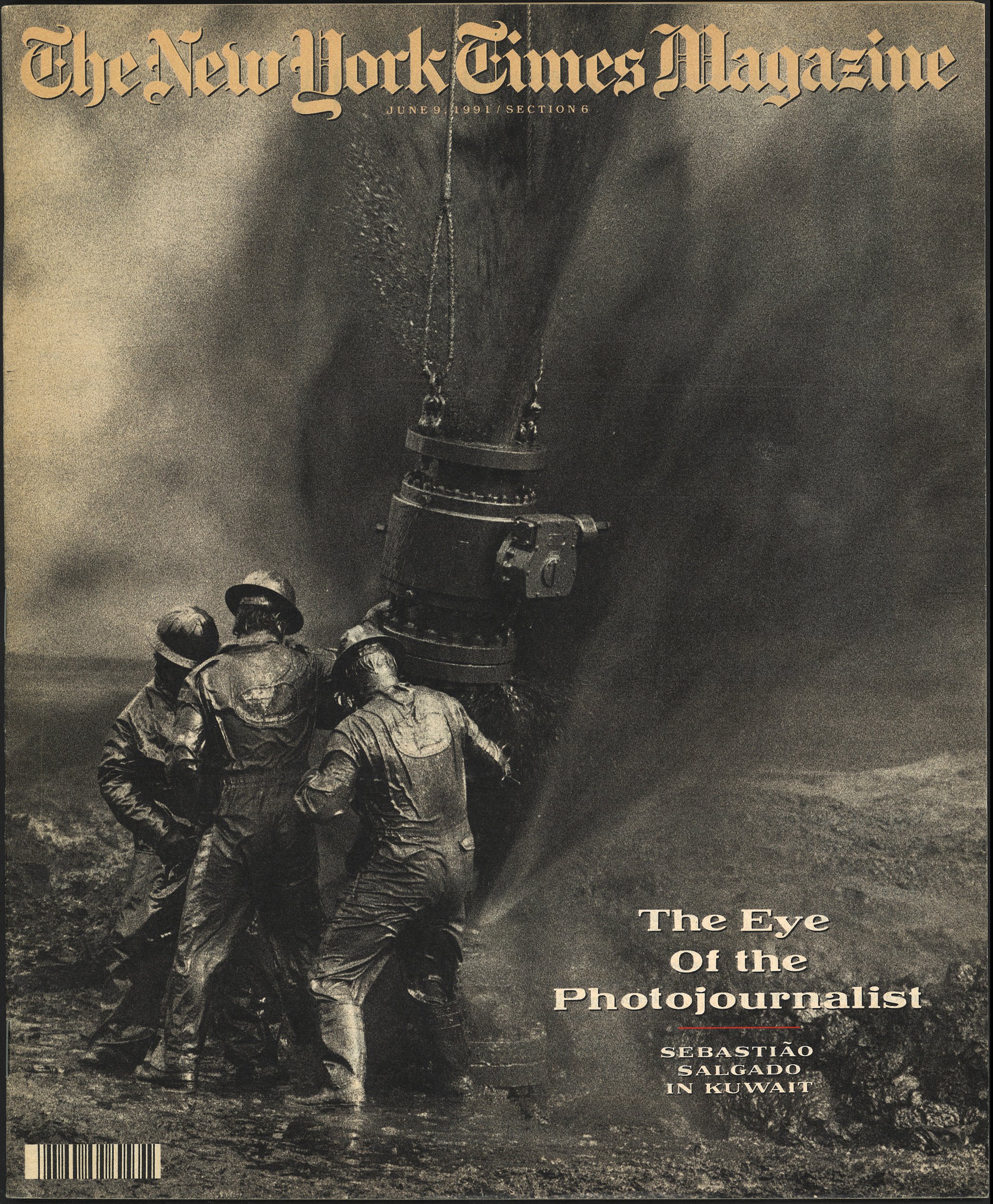

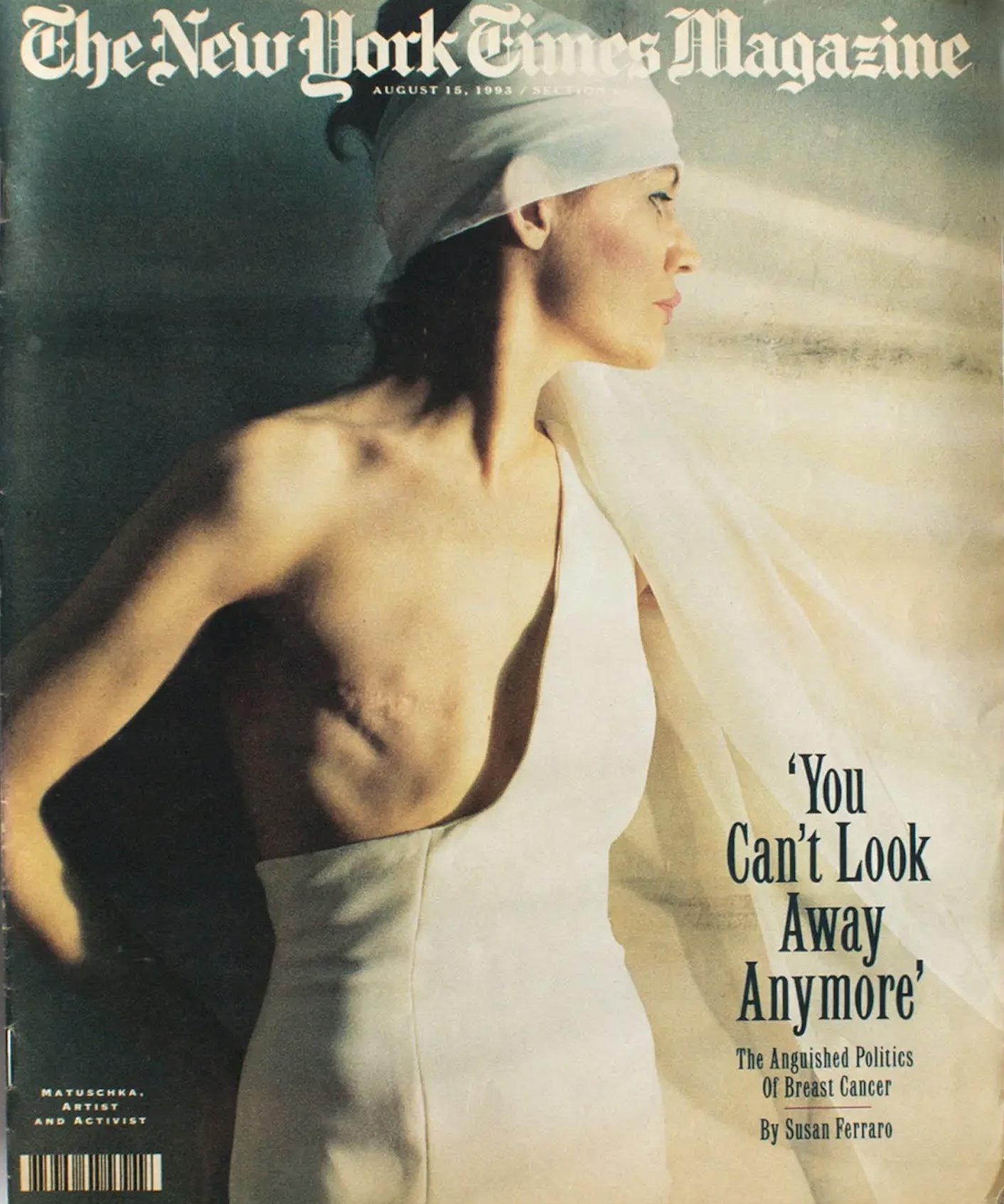

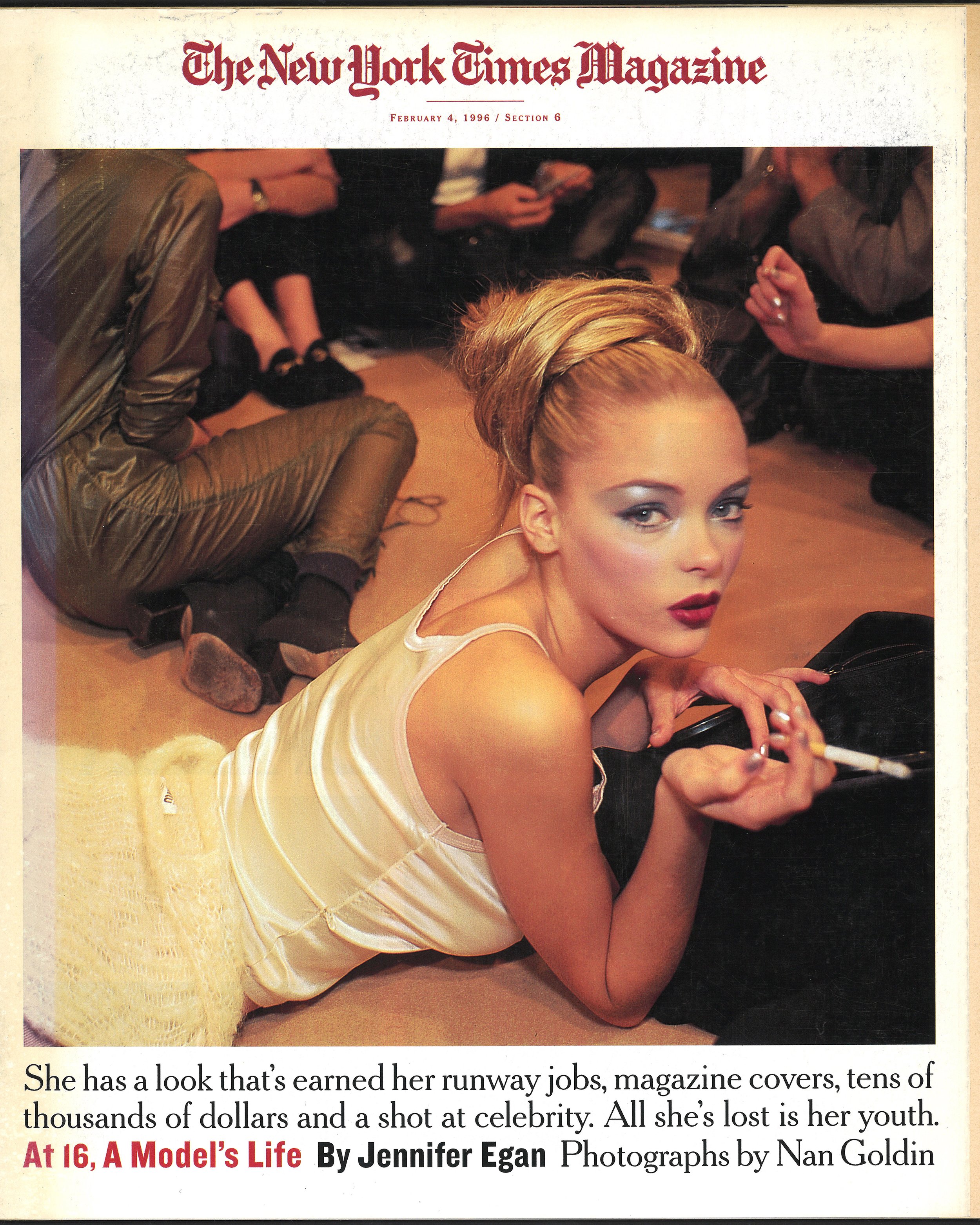

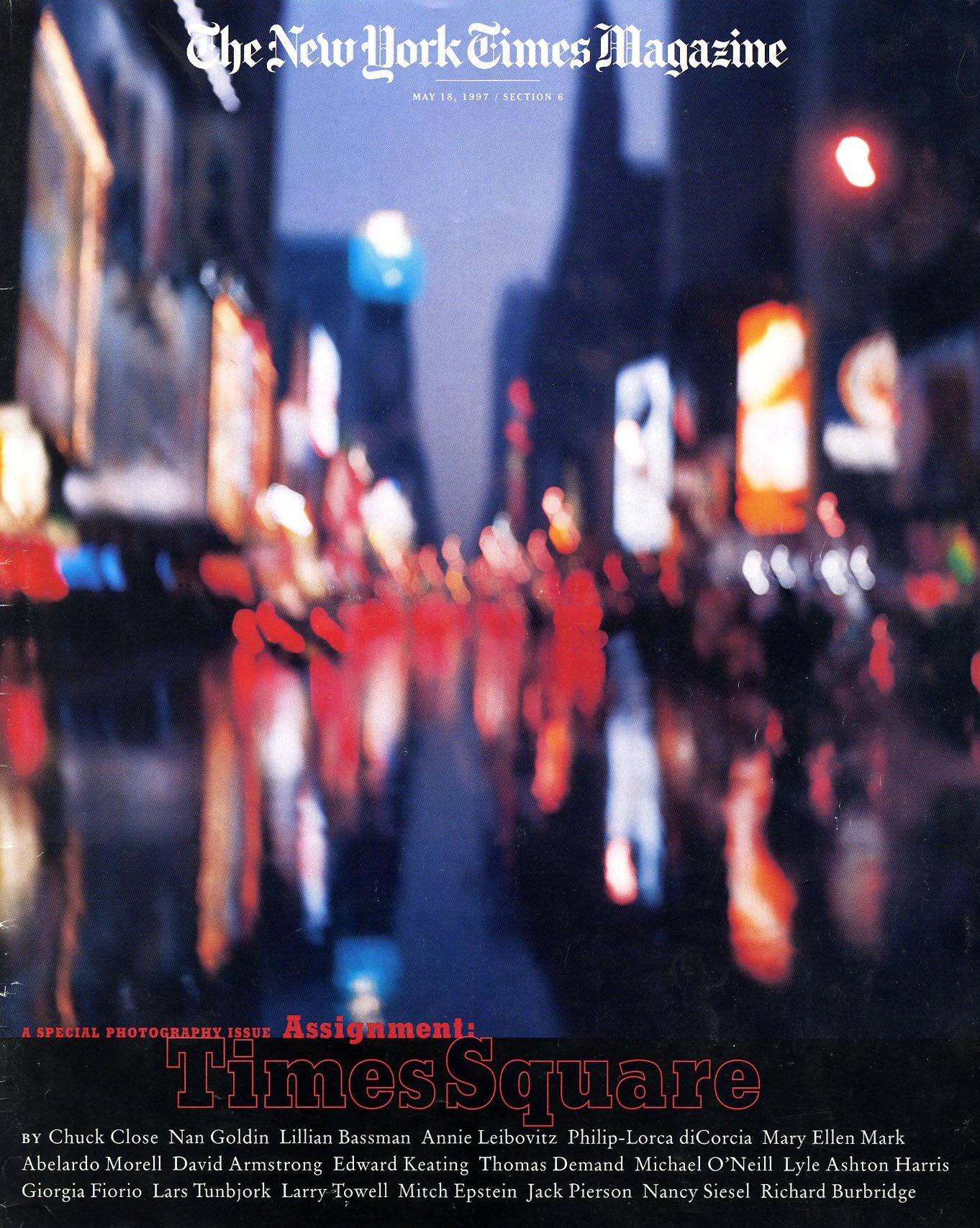

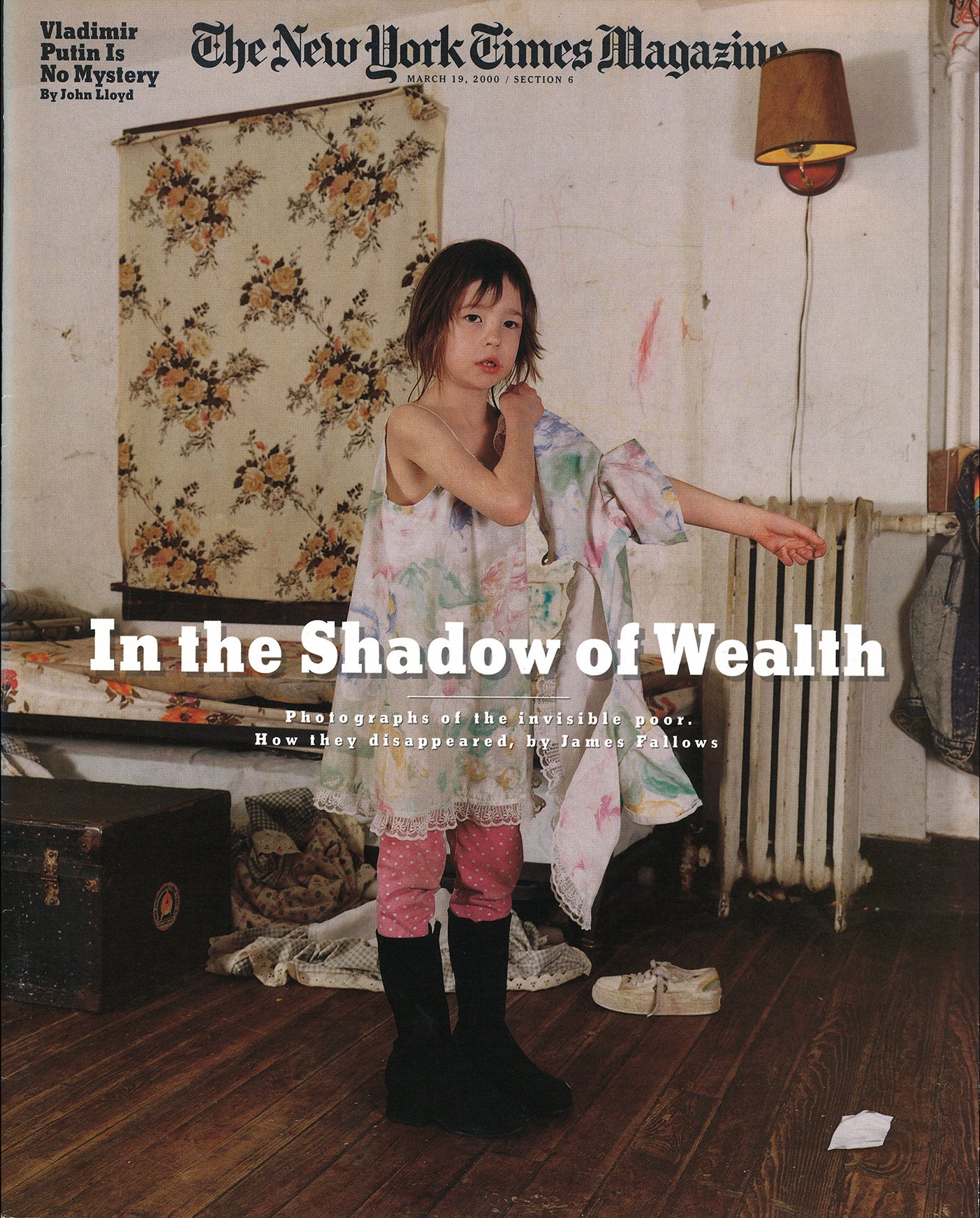

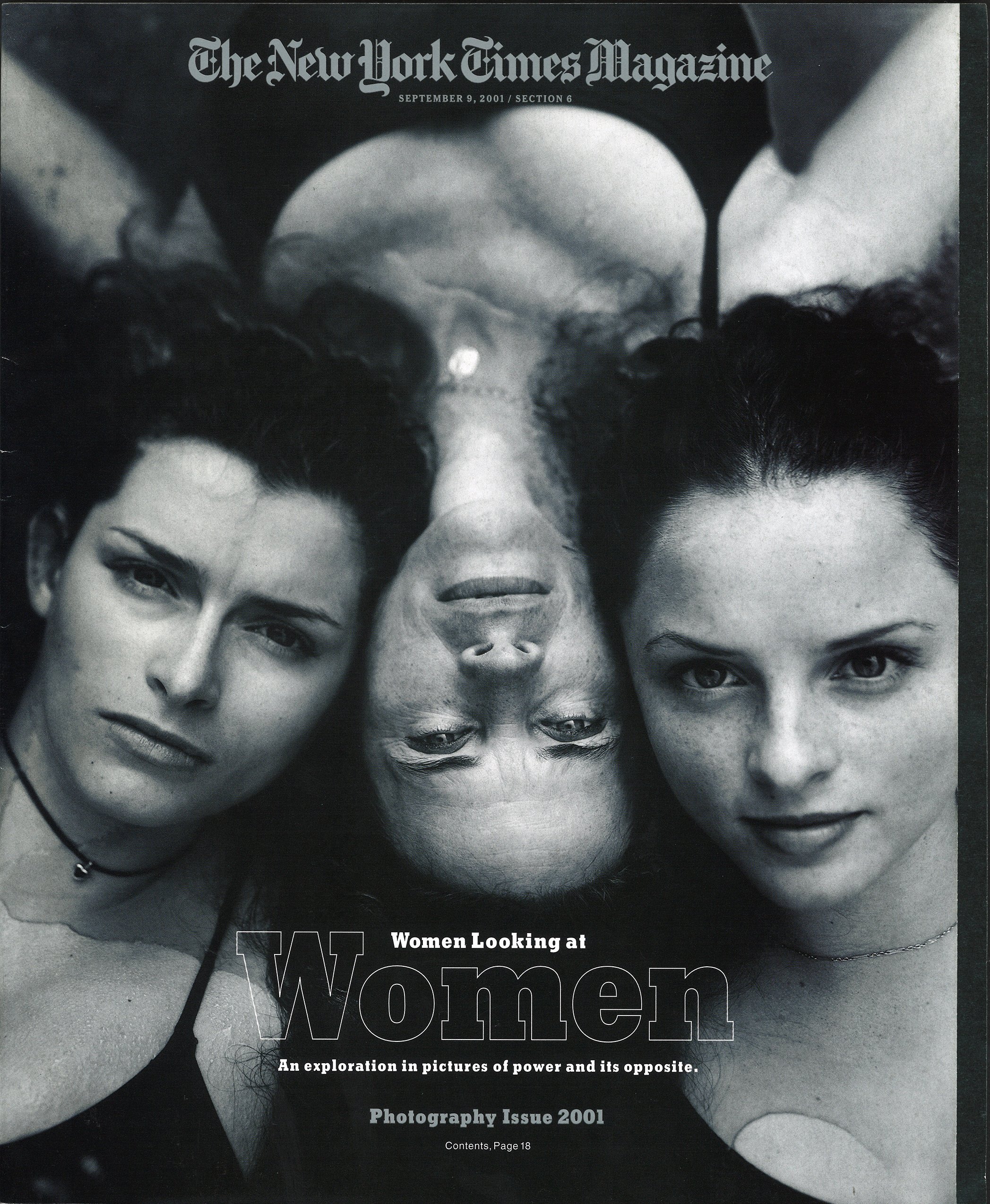

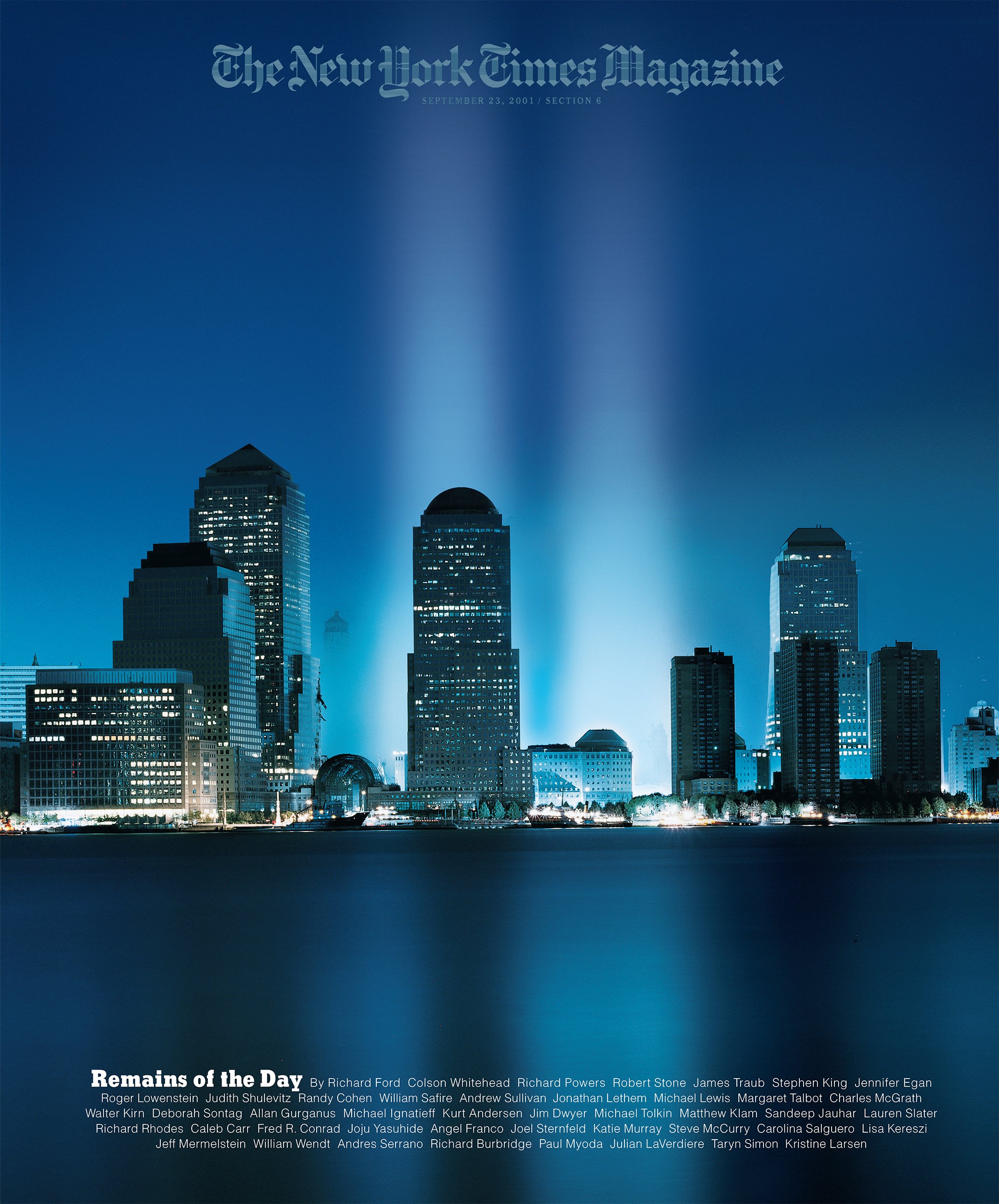

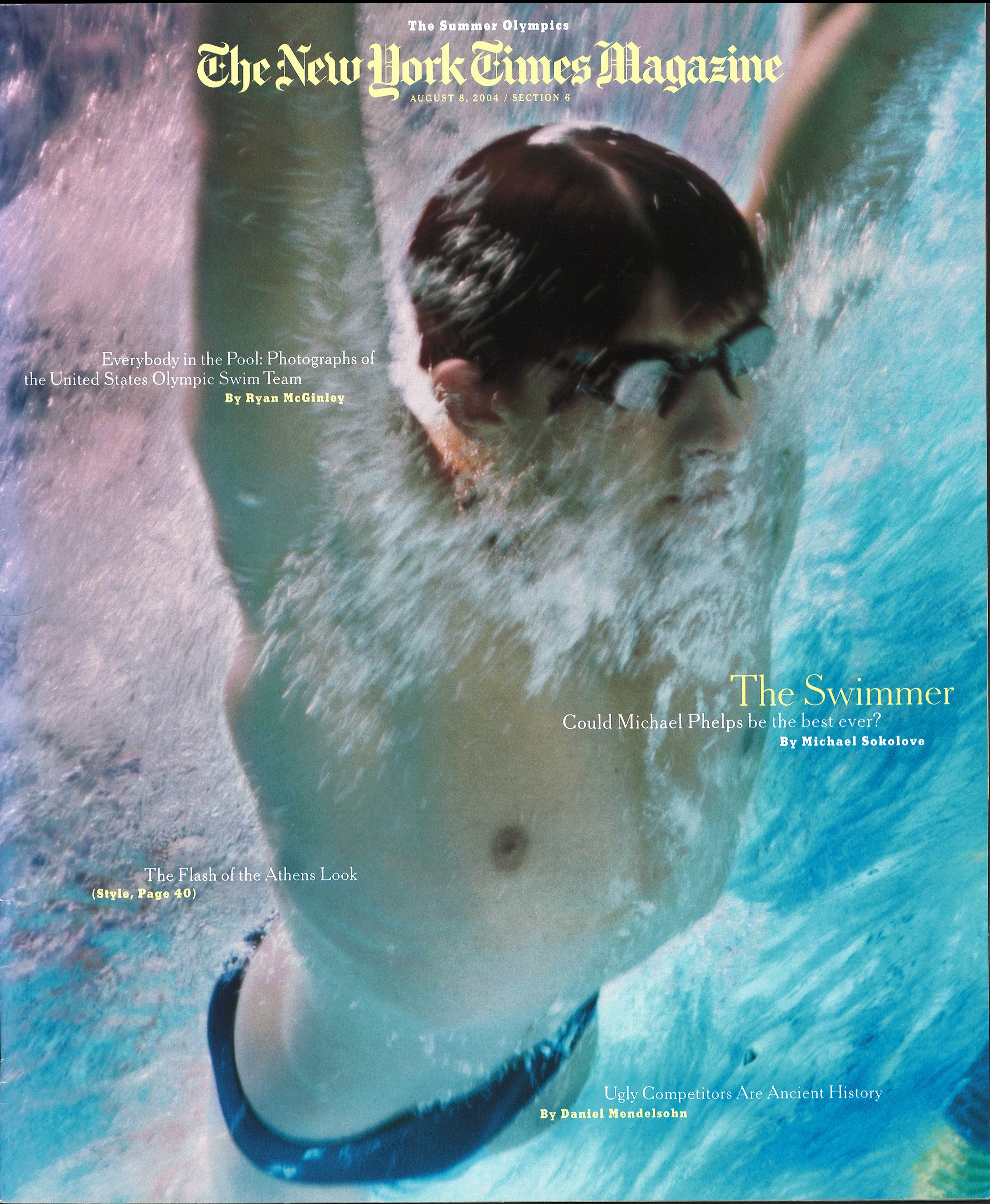

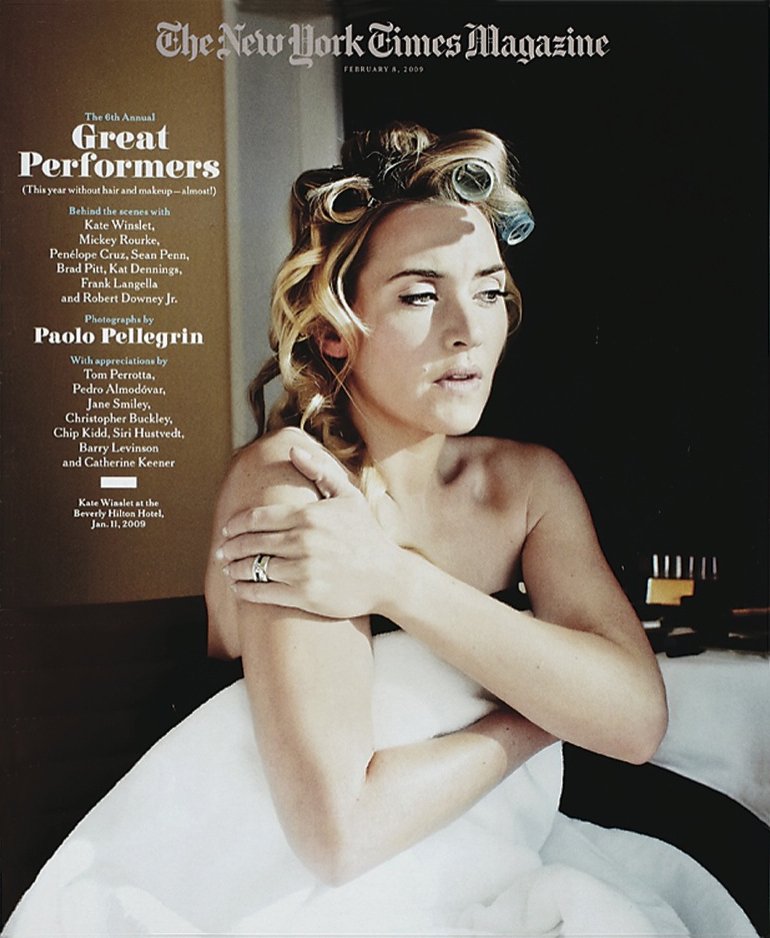

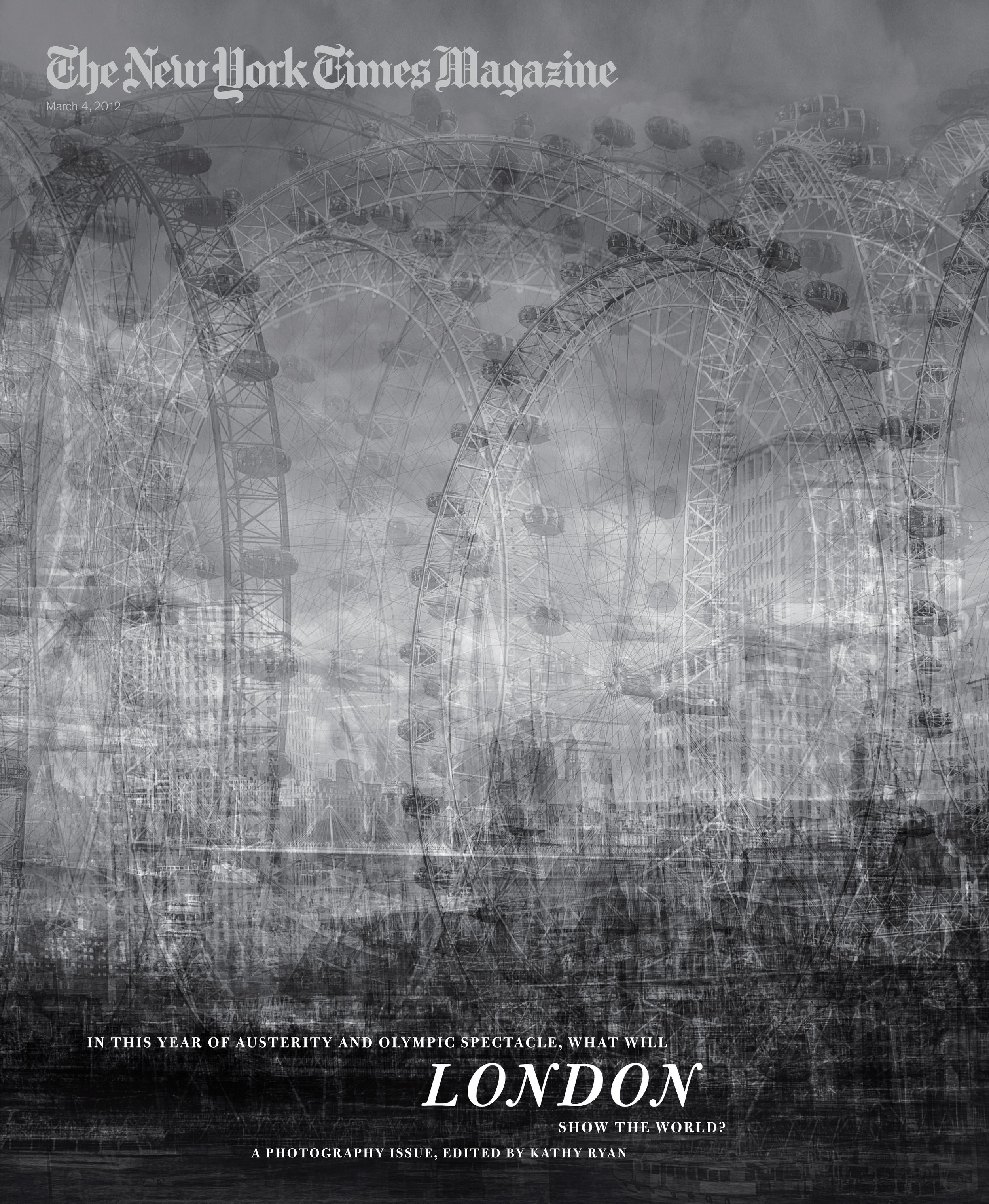

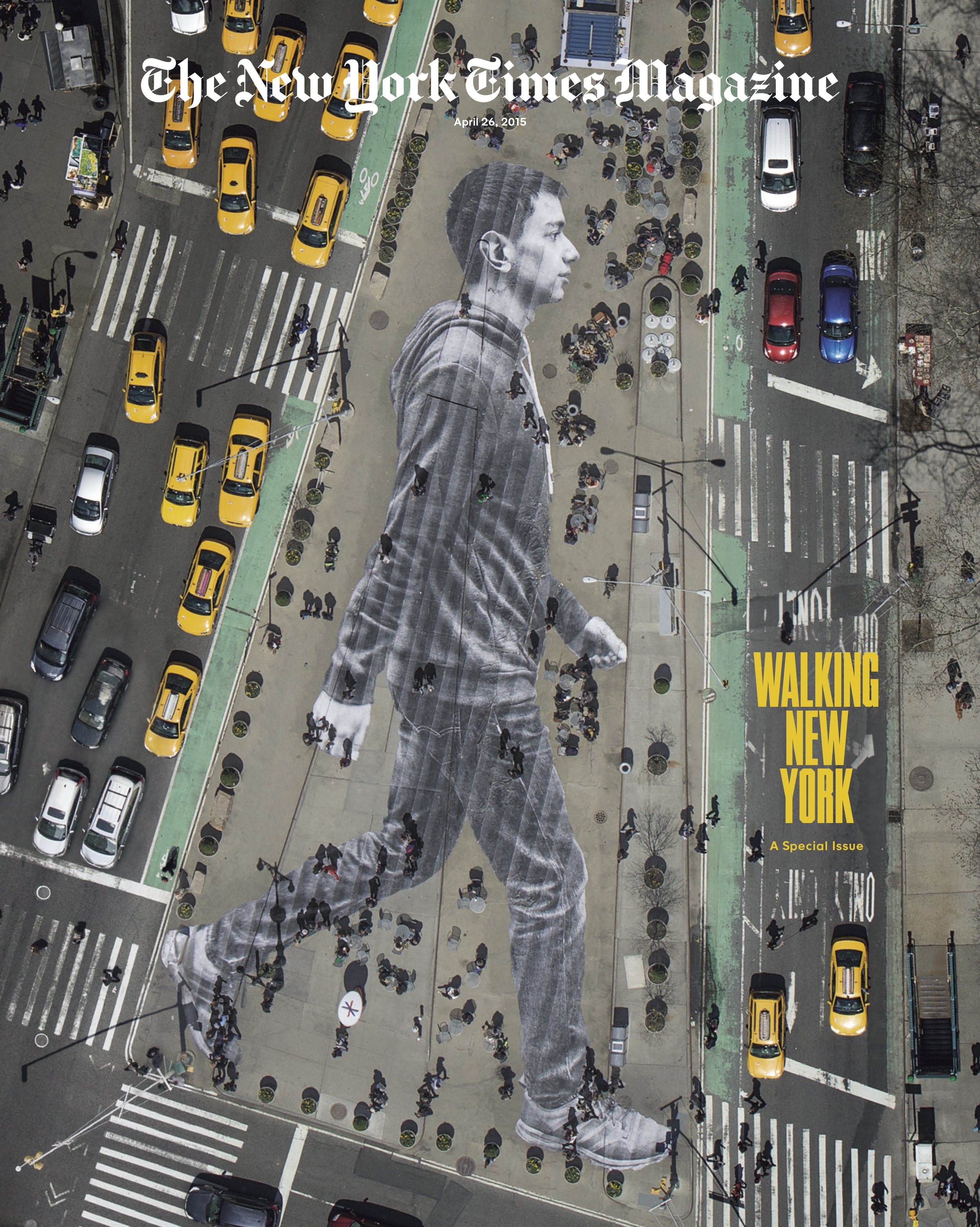

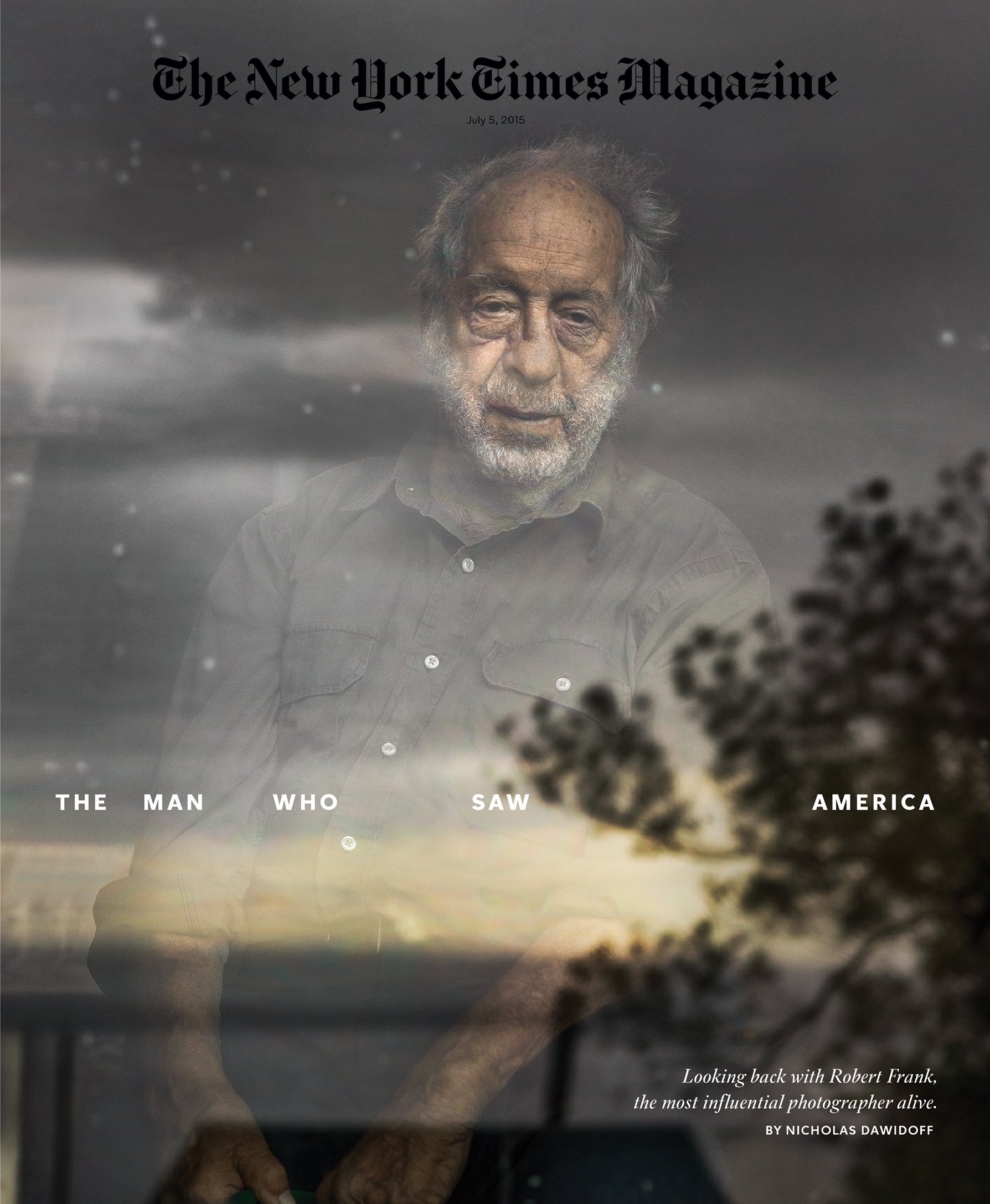

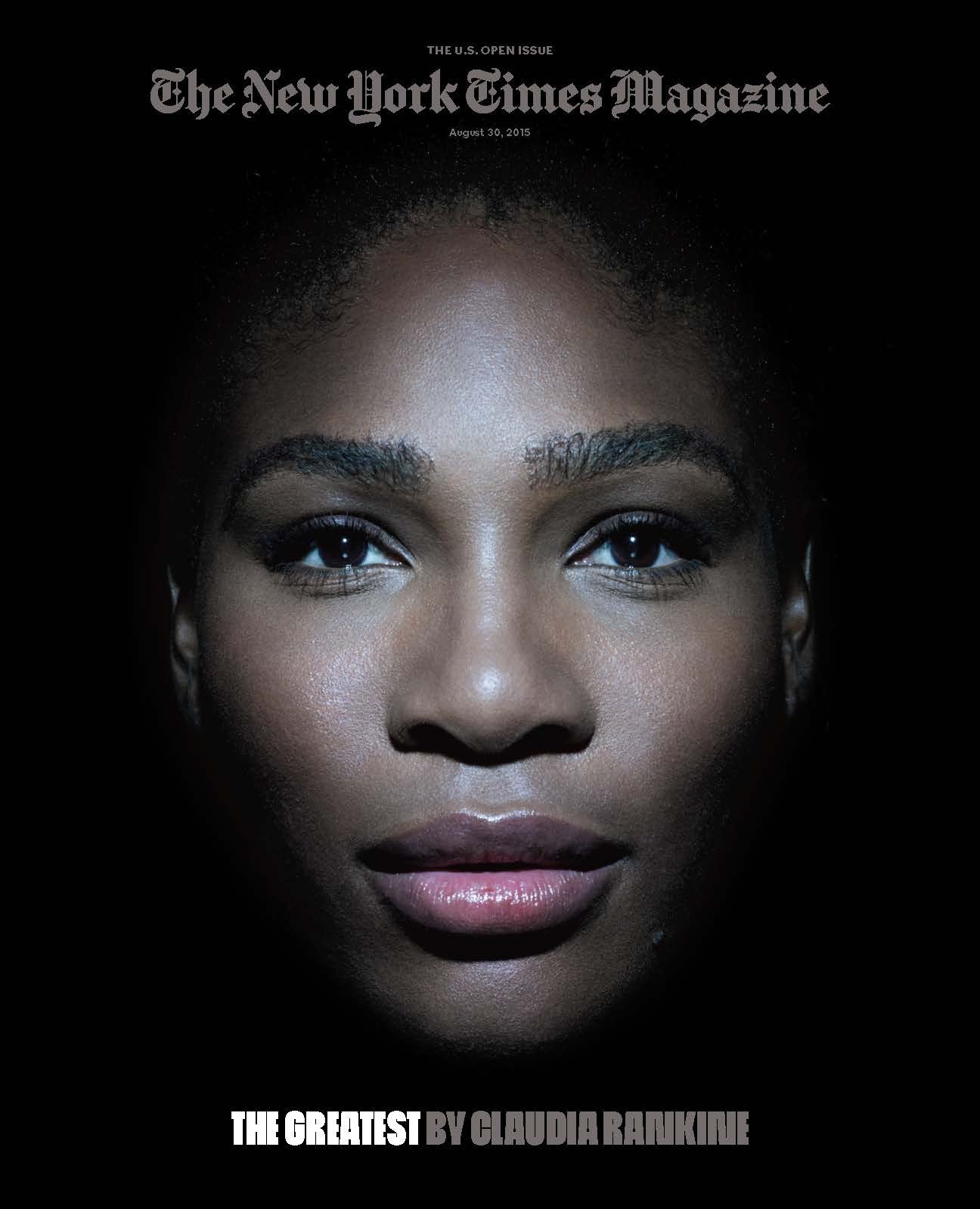

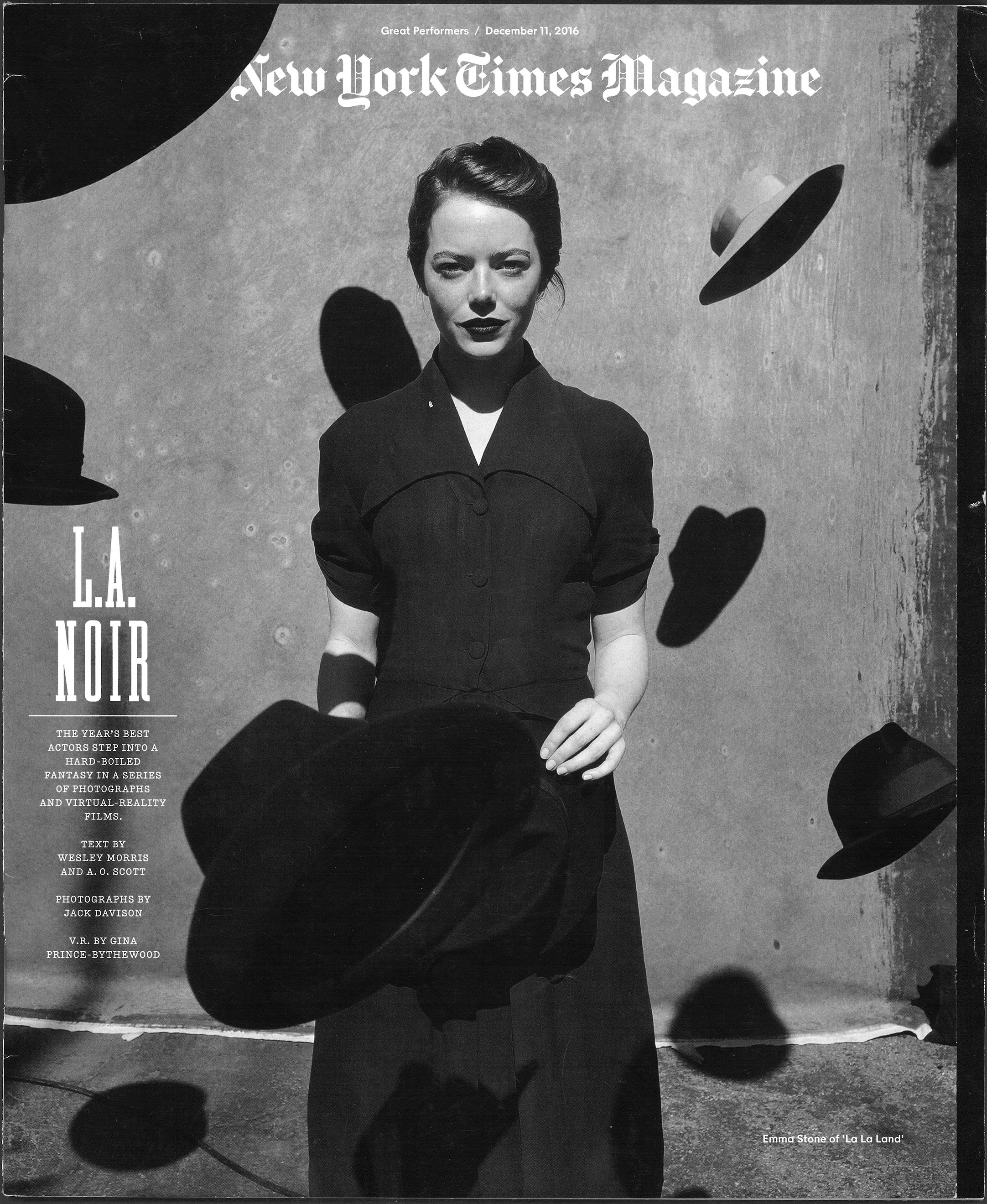

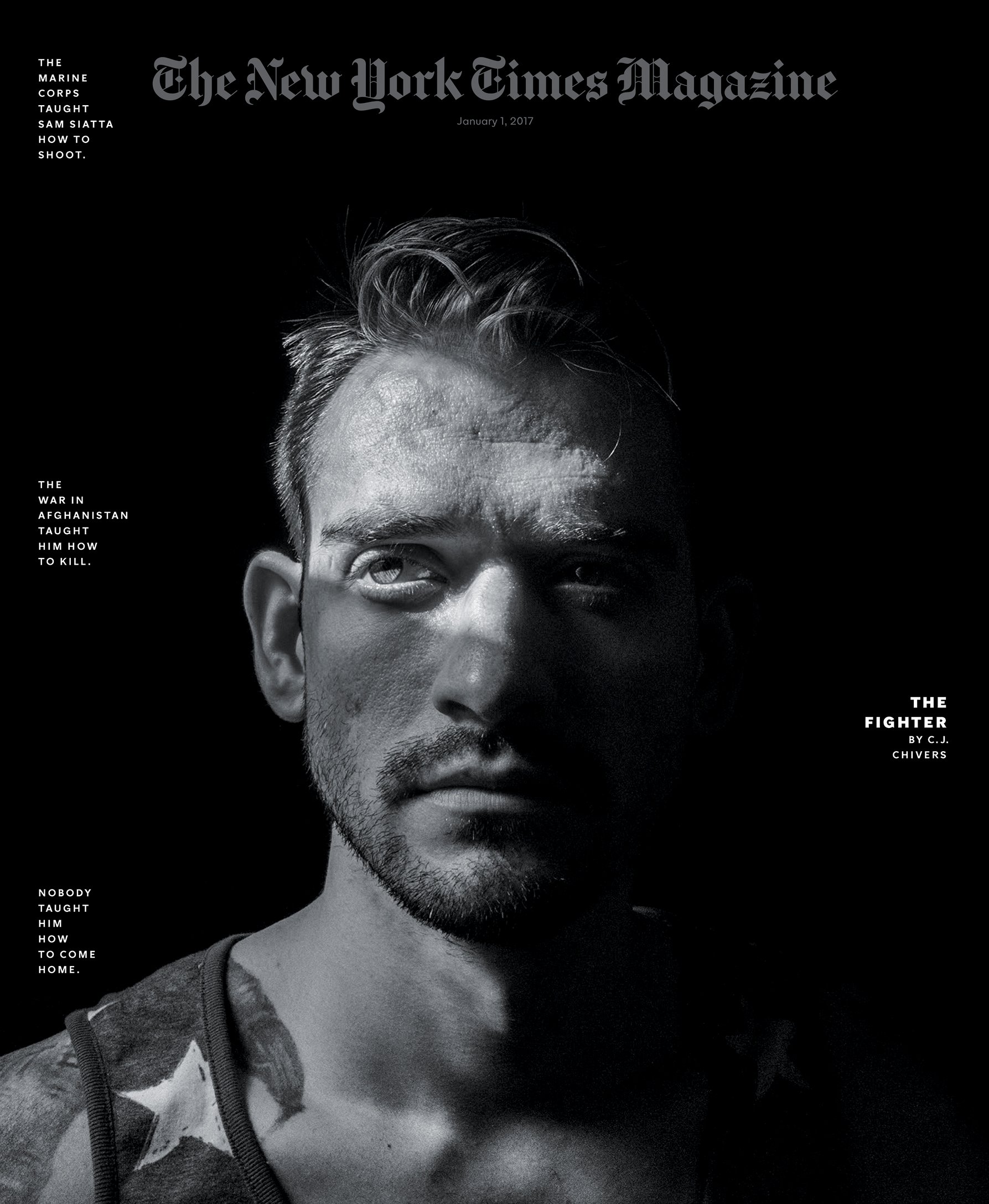

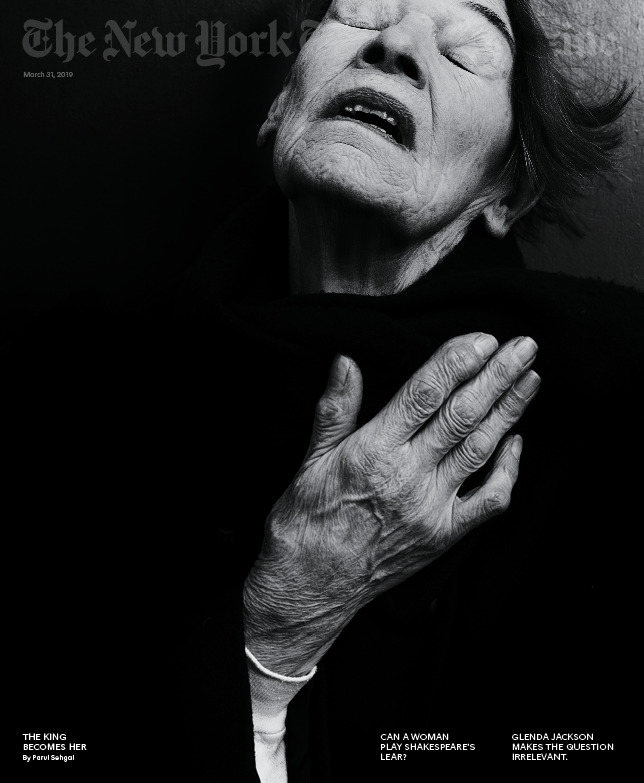

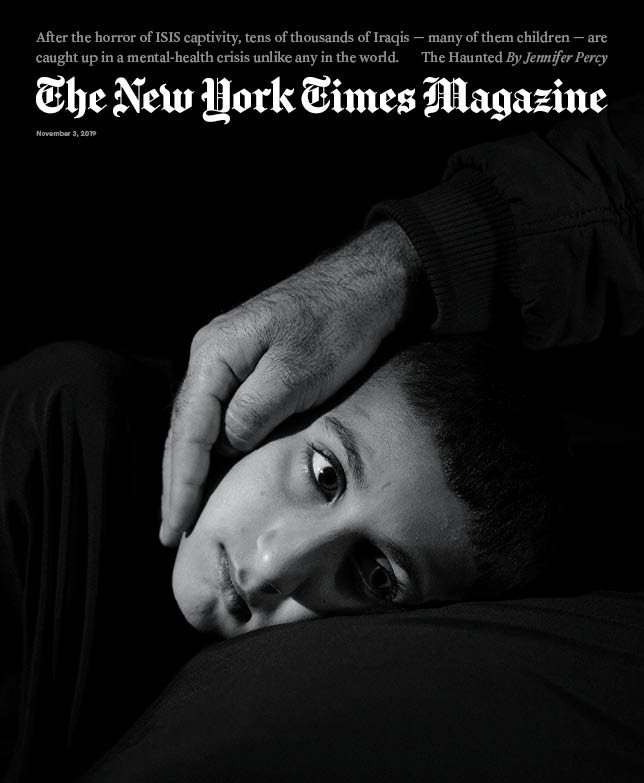

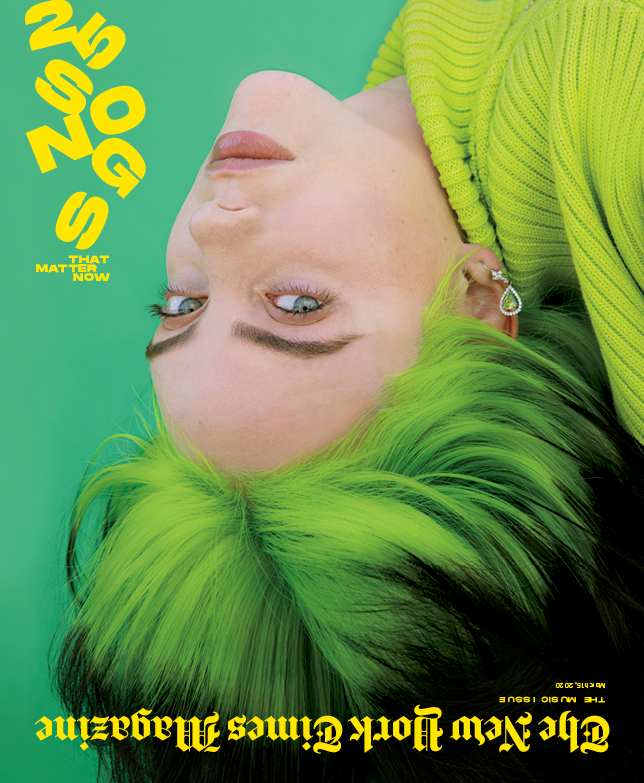

A collection of Ryan’s favorite covers spanning her 38-year career at The New York Times Magazine.

“When I started out, you turned to magazines and papers and books for the photos. That was it. And now it’s just completely different. People see hundreds and hundreds of pictures every day. So where is our place in that?”

The New York Times Magazine braintrust (from left): editor Jake Silverstein, creative director Gail Bichler, and Ryan. (Photograph by David La Spina/Esto)

George Gendron: I’m going to dive right in here with a question that I shared with you before, and that is that the vast majority of people involved in, certainly in print media, never really understand or understood what a photo editor really does. And I think people really don’t understand, especially in this day and age, what the job really entails. And so I’m wondering if you were standing up in front of, let’s say, a class of young, would-be photojournalists and videographers, how would you answer the question, What does the director of photography for The New York Times Magazine—what do you do?

Kathy Ryan: Well, I work with a team of photo editors. We’re a small team and the job is basically to conceptualize and figure out the photographic approach for each of the stories coming up. So we do, you know, coming up with ideas and assigning photography to accompany text-driven pieces. And that’s the majority of what we do at The New York Times Magazine.

But we also initiate ideas for photo essays, where it comes from either a photo editor or a photographer, and we pitch those ideas in the same way a story editor would. So the photo editor’s job is basically—the director of photography, my job—is to work with a team, look at the stories that are coming up, and as fast as they’re going onto the schedule or being assigned to writers or being assigned to photographers, we make it happen. So in some cases that might mean, it’s a writer driven piece, and the main thing I do is with the team, figure out what’s the best approach.

Do we want to approach it in a documentary fashion? Send a photojournalist? Do we want to approach it as studio portraiture? Is this a story that calls for conceptual photography where we come up with an idea and create it in-studio, whether that’s still life or something where we build sets? There’s all different ways to commission the photography.

So first thing is meeting with Gail Bichler, the creative director, Jake Silverstein, the editor-in-chief, and some of the other top editors, depending on the story. And we have a weekly art direction meeting with the team, where we’ll meet and talk about what’s coming up. Jake will give us an idea and what this photography or art—sometimes it’s illustration—needs to accomplish.

Most of the time we are making the photography happen at the same time the piece is being written. Sometimes we have the manuscript first, but we’re often simultaneously figuring out what we’ll do for the photography.

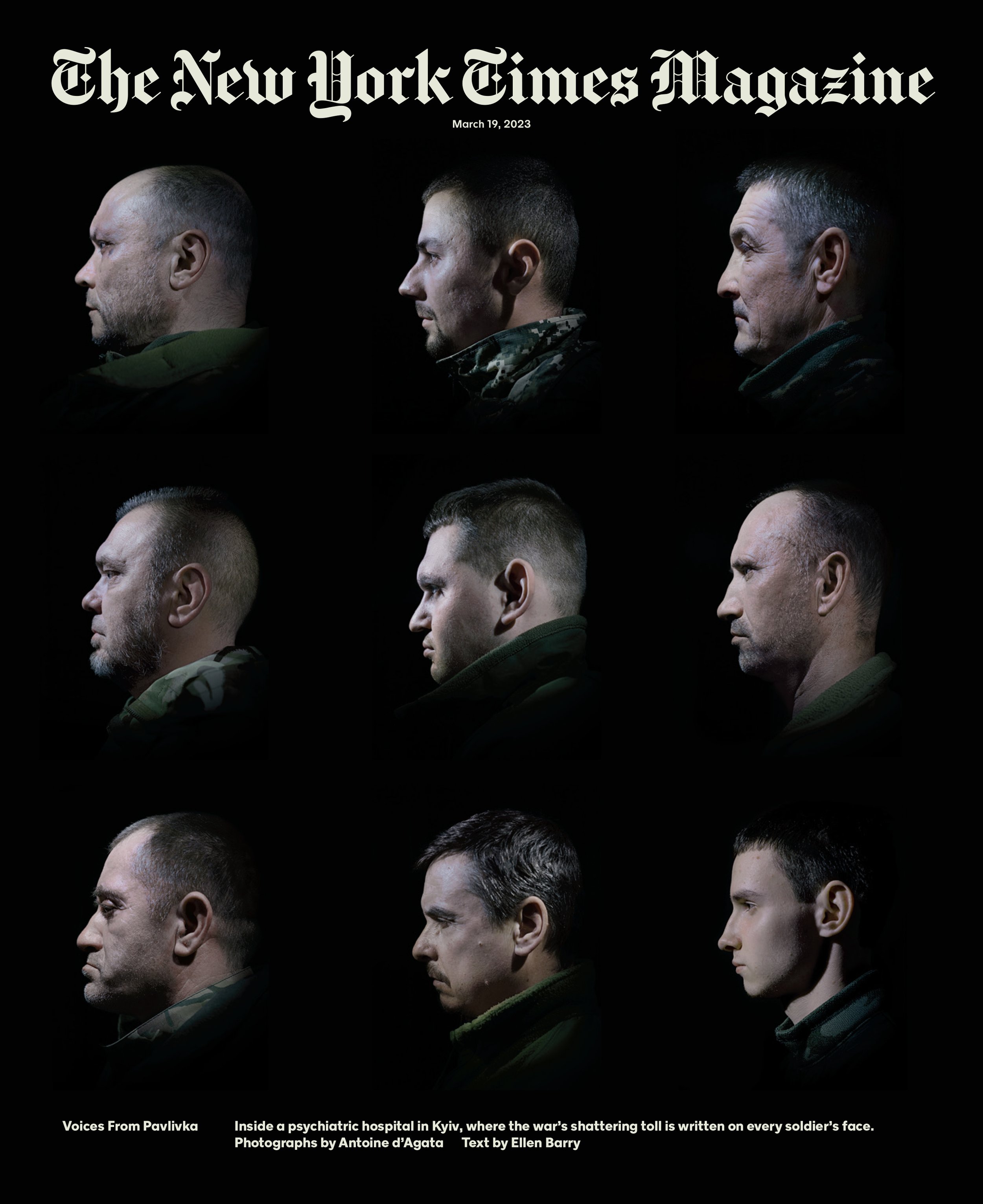

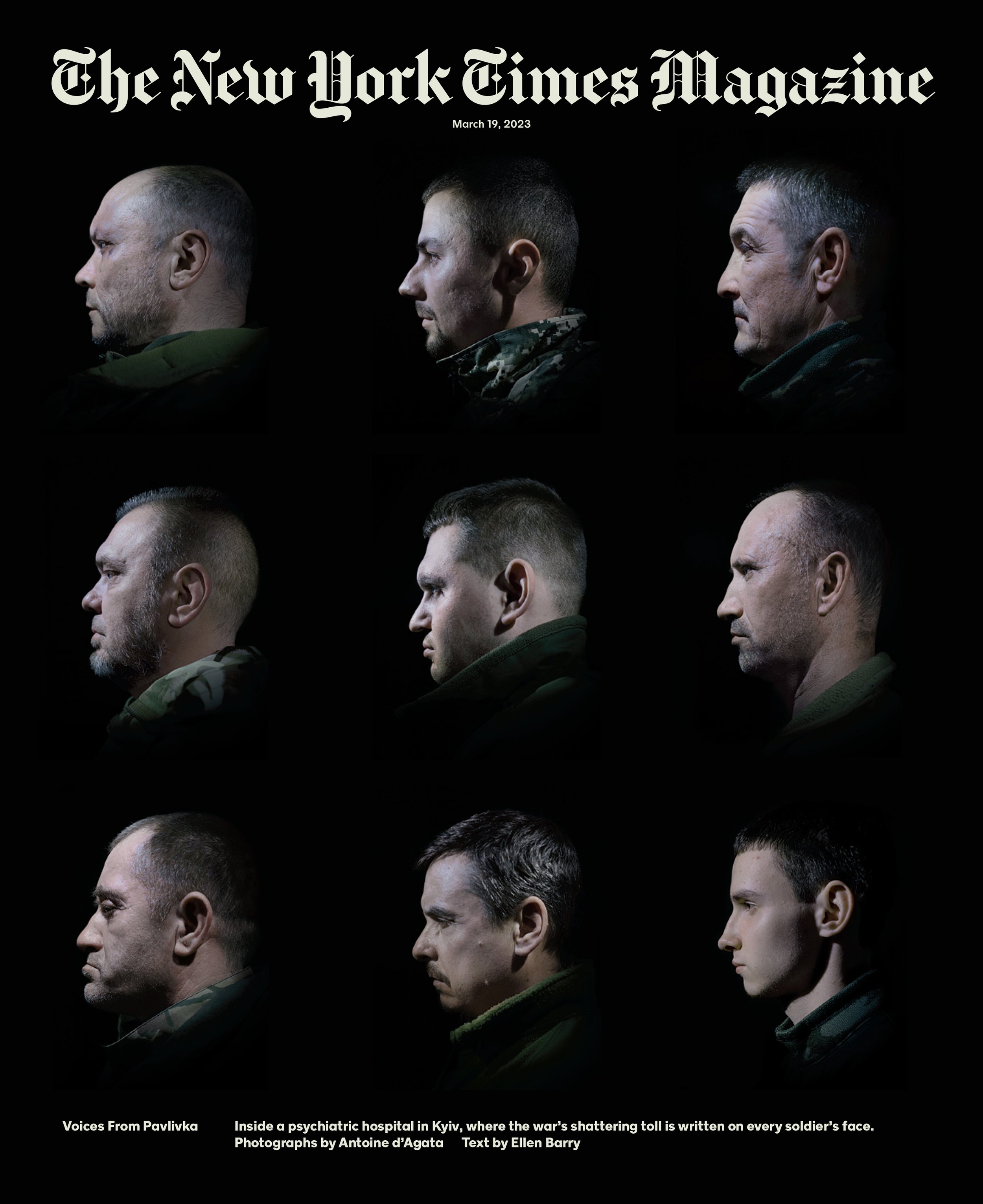

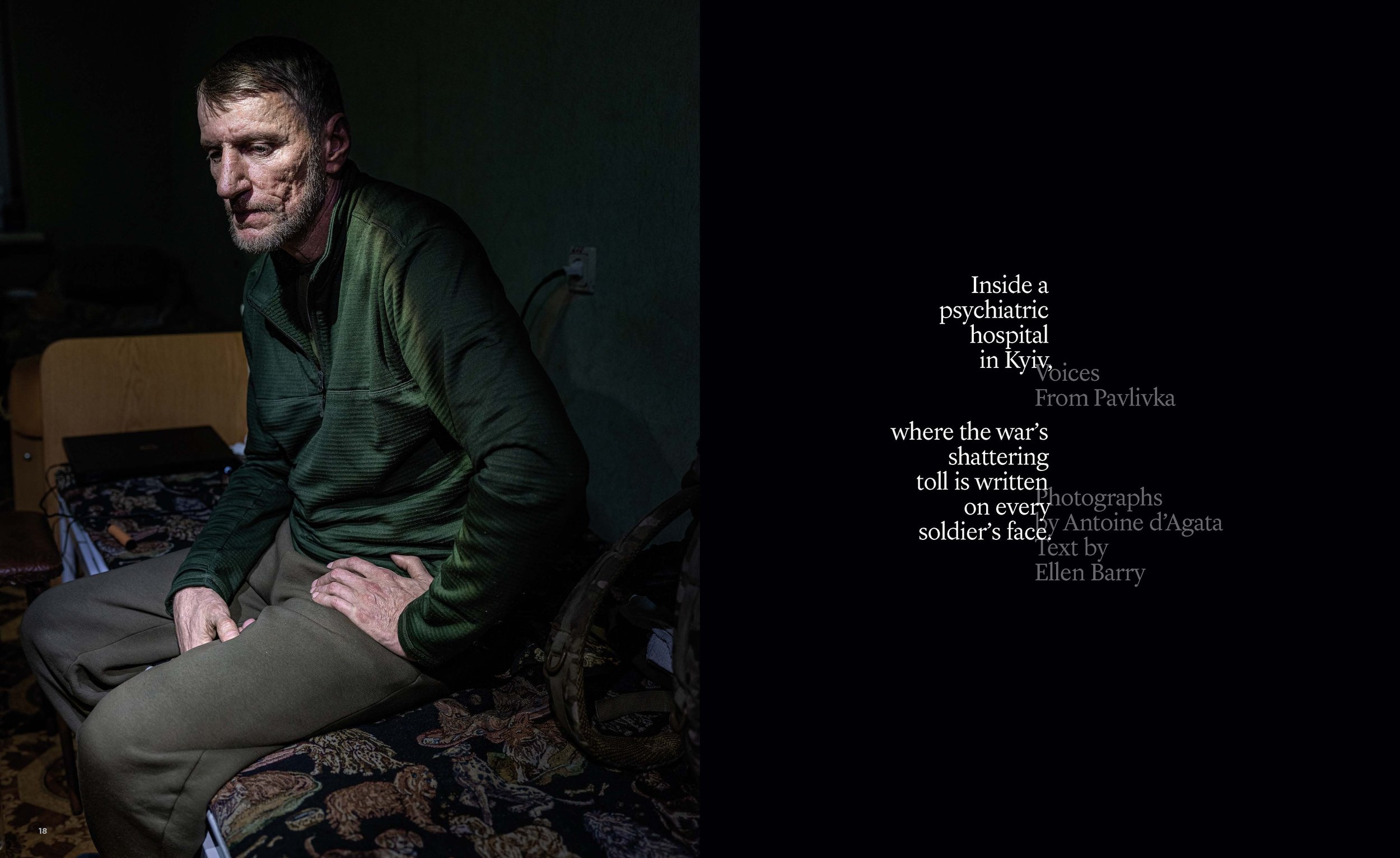

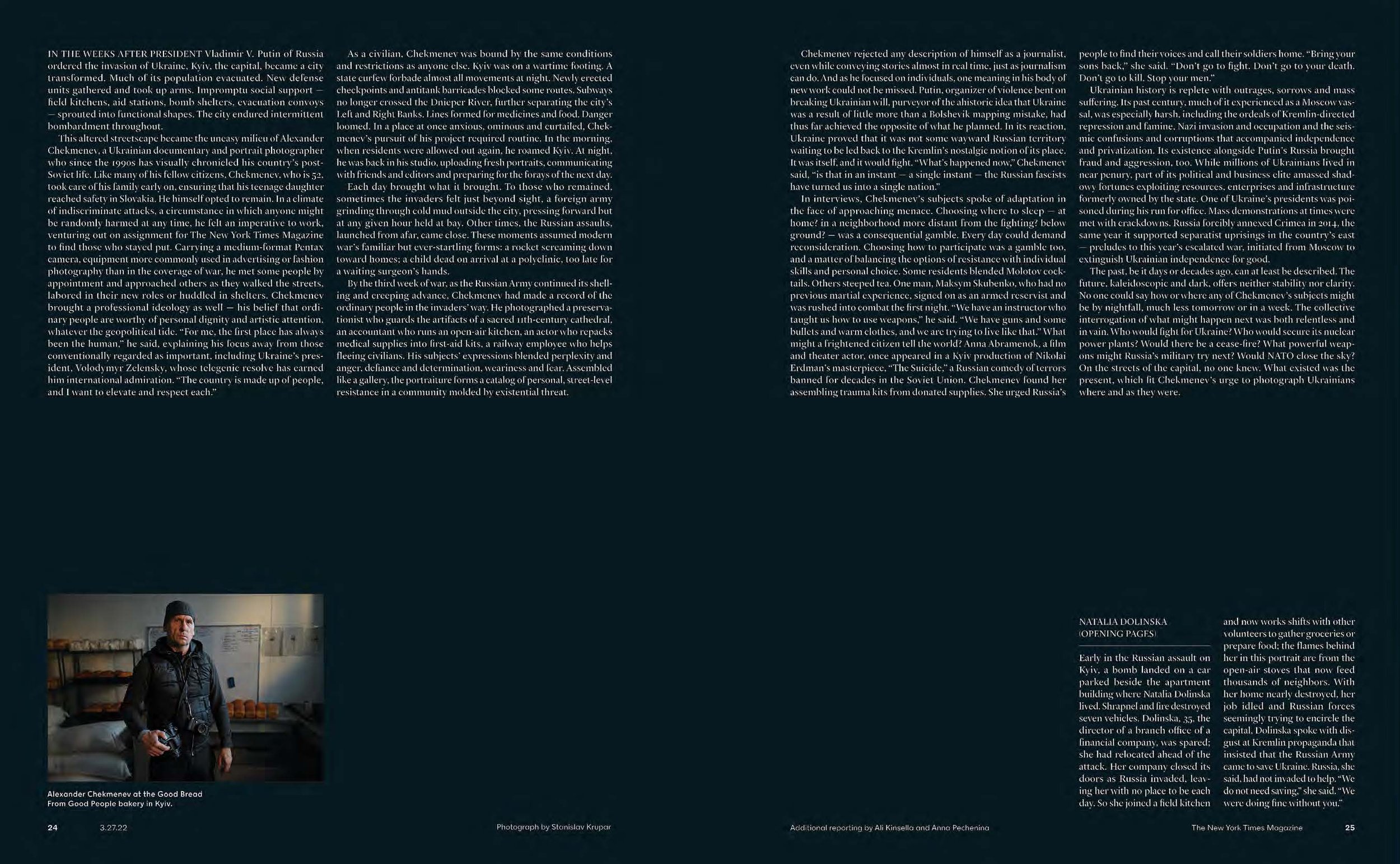

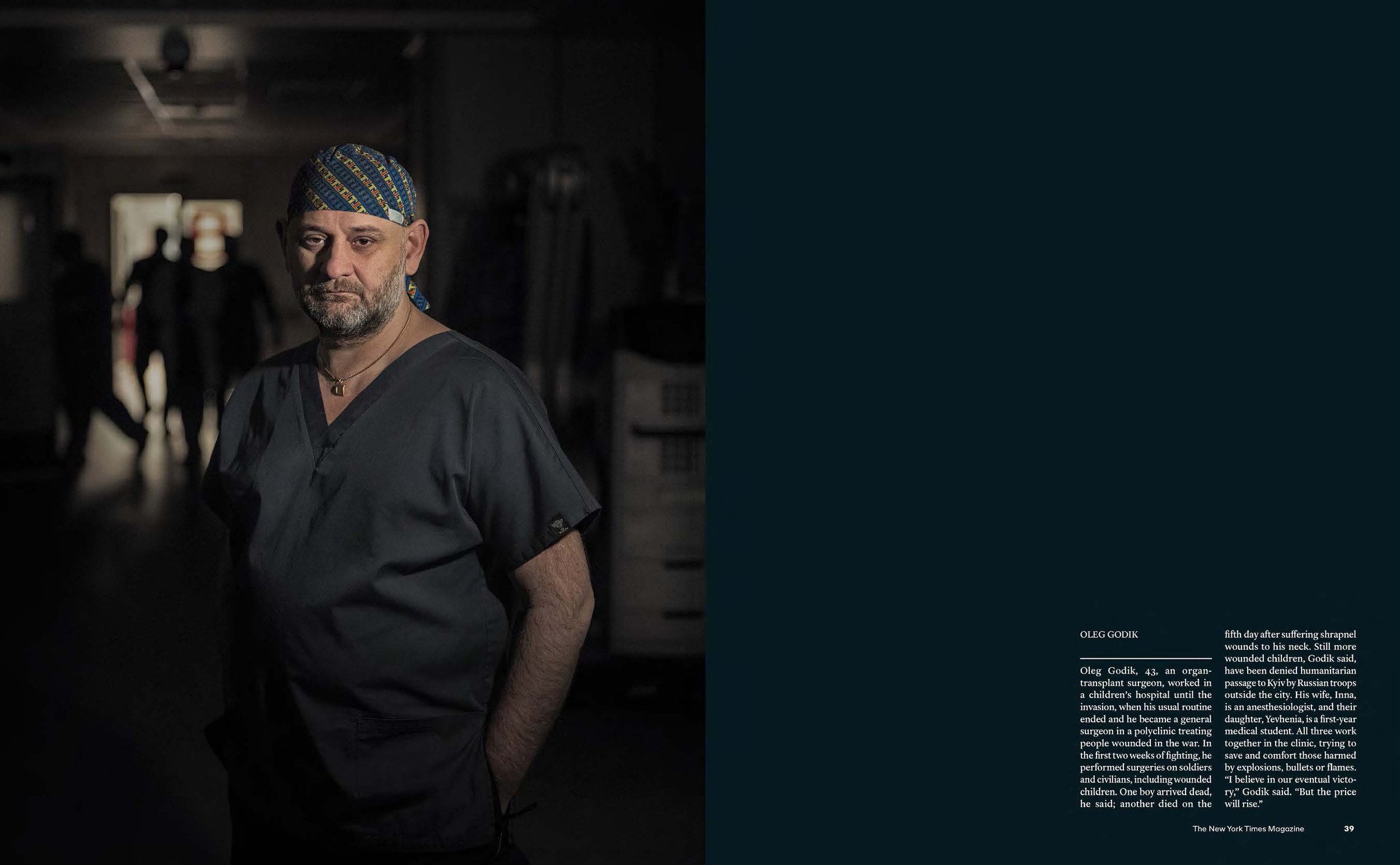

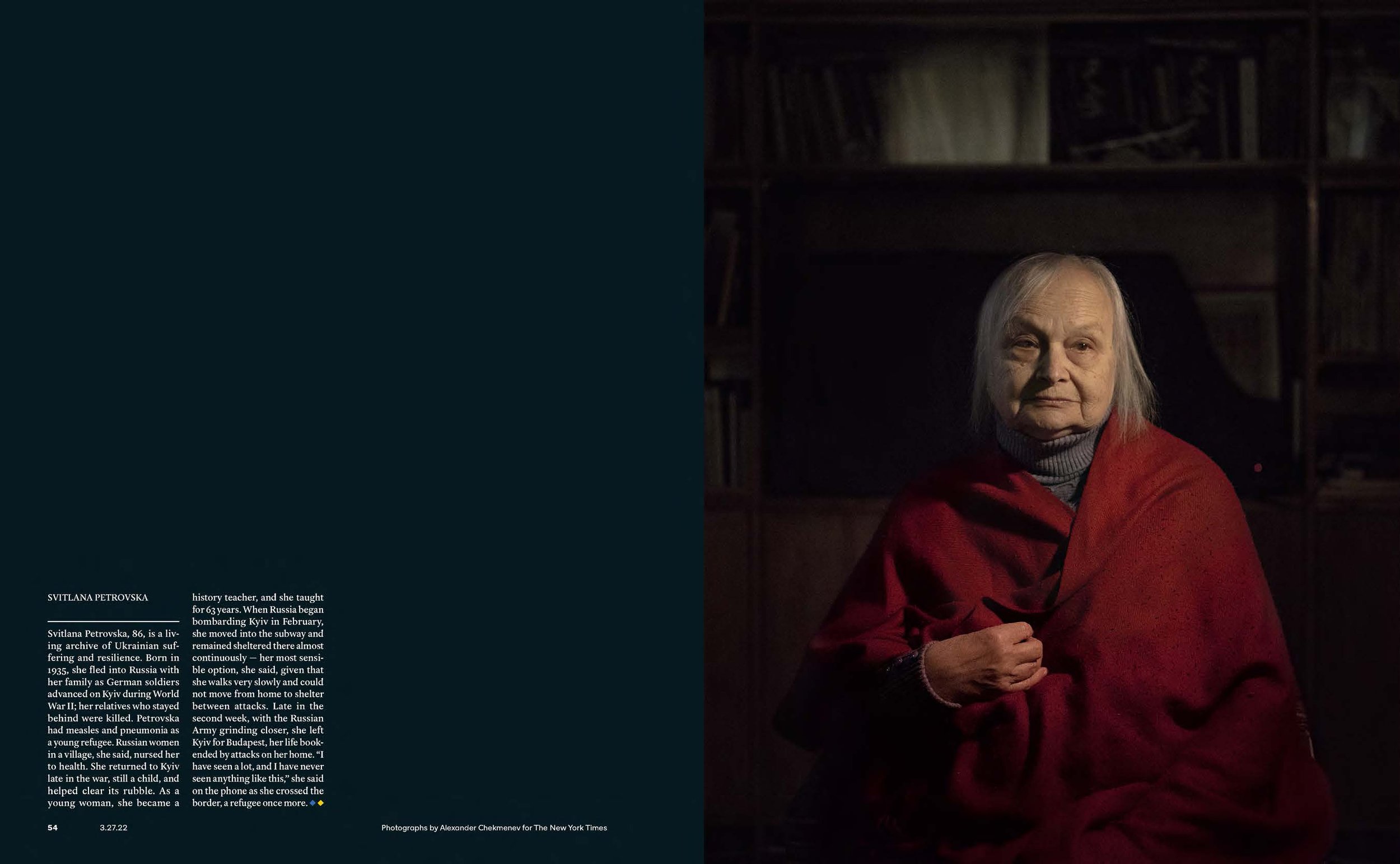

Voices from Pavlika Photographs by Antoine d’Agata/Magnum & Citizens of Kyiv Photographs by Alexander Chekmenev

We cover all sorts of subjects. More so than almost any magazine. Our range is very broad—from the big, internationally reported pieces to The Way We Live Now features to the cultural stories. So we kind of cover it all, which, of course, makes it the most exciting job on the planet. Because one minute we’re producing a big shindig in Hollywood, and the next minute we’re doing something far more serious—figuring out how to cover the invasion in Ukraine. But then, of course, the most important decision you make is who’s the best photographer for the assignment.

And then figuring out the cover is its own thing. So a lot of my time, and Gail’s, and Jake’s, and our team’s, is spent figuring out what we should try to do for the cover. And right away: Is it photography? Is it illustration? Is it a photo illustration? Do we think this is a story that we want to go documentary? So that gives you some idea.

The other day I was talking with Jake and he said something I thought really made sense. He said, “Basically we do three things. One is artistic, obviously. One is the expression of ideas. And then the third is deadlines.” You know, it’s a weekly and I cannot stress enough that it’s always at an accelerated pace.

Just about everything we do is full throttle, meaning as fast as we’re assigning one thing, we’re thinking about the next one. We’re trying to get it lined up.

George Gendron: I’m curious, you talked about the cover. You have one luxury that the rest of us in the mainstream magazine industry have never had, which is you don’t have to worry about newsstand sales. And I think that’s really liberating. And I’m curious about your response to that. So how do you think about the cover? What’s the role of the cover within the Sunday paper?

Kathy Ryan: I think the role of the cover is to stand out. So when somebody opens up their Sunday paper, their bundle, you want the cover to call attention to the stories inside. So I think of it, first and foremost, to get people into the magazine. We’re very aware of how fortunate we are that we don’t have to compete on the newsstand. That has always been a gift because it just means there’s a freedom—the decisions can be made in terms of what’s the best artistic approach.

And Jake is a big believer in that. What does that mean? Maybe it means we can do something a little bit more obscure, less direct. Sometimes we have a chance to play around with more poetic imagery that wouldn’t stand out on a newsstand, but it’s a really thoughtful, beautiful picture.

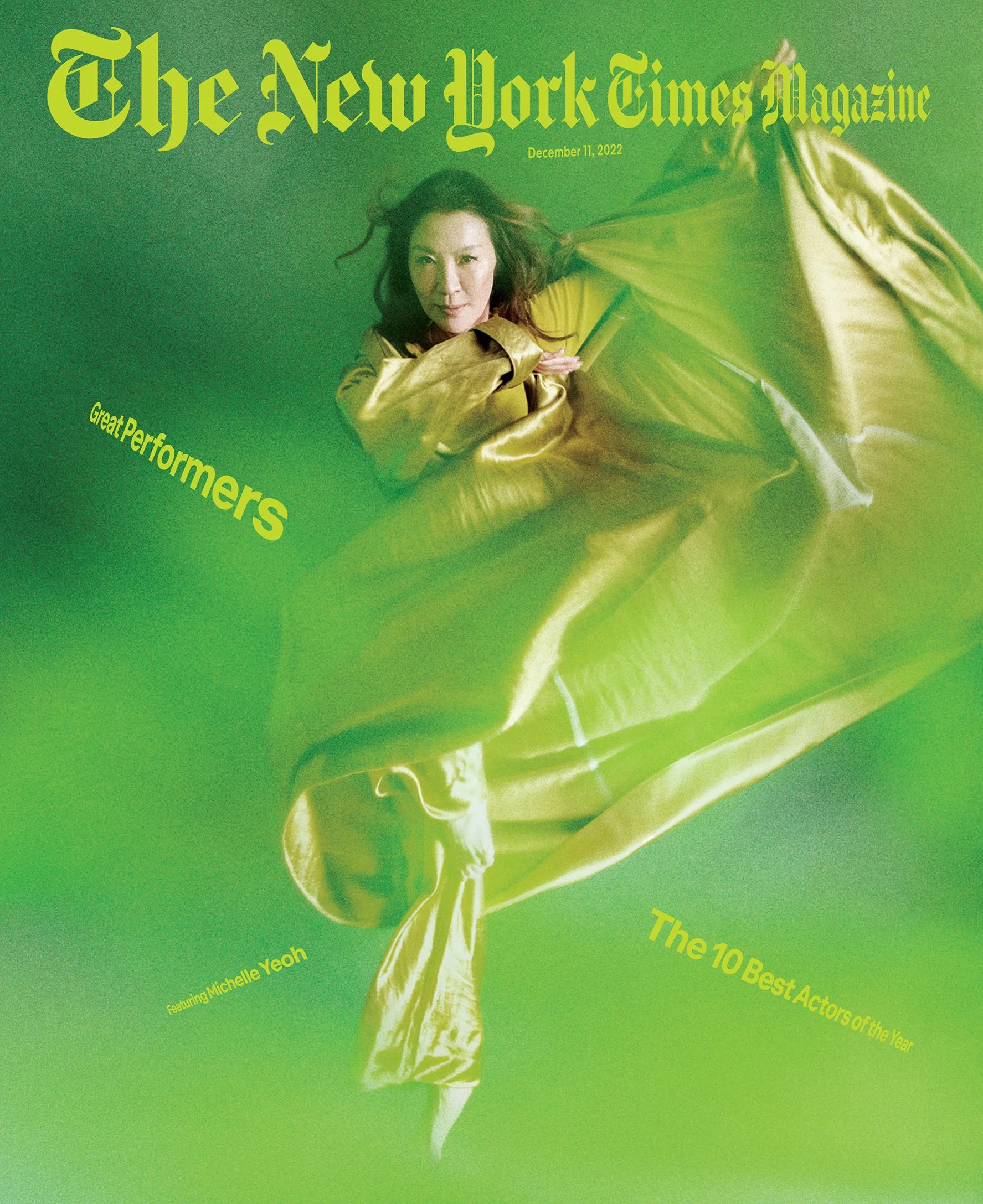

Many of the conversations that we have, between me and Gail and our design and photo teams, have a lot to do with that. What works as a cover image is often different. But then again, our covers vary widely. There’s not a look to them because one week it’s our Great Performers portfolio that we do once a year, pegged to the Oscars. And then another week it might be pure documentary photojournalism. So we have a tremendous variety and we try to shift according to the needs of a particular story.

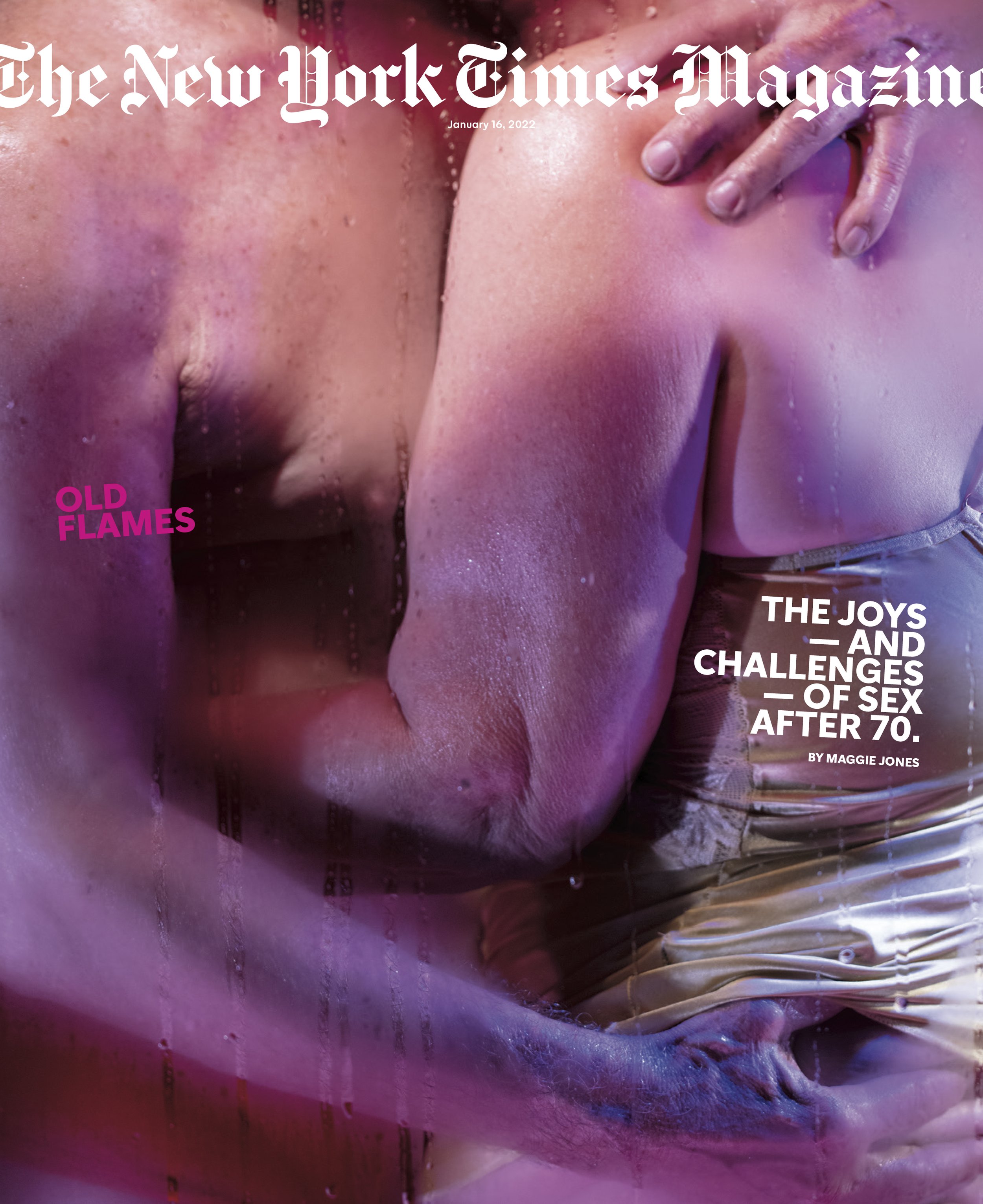

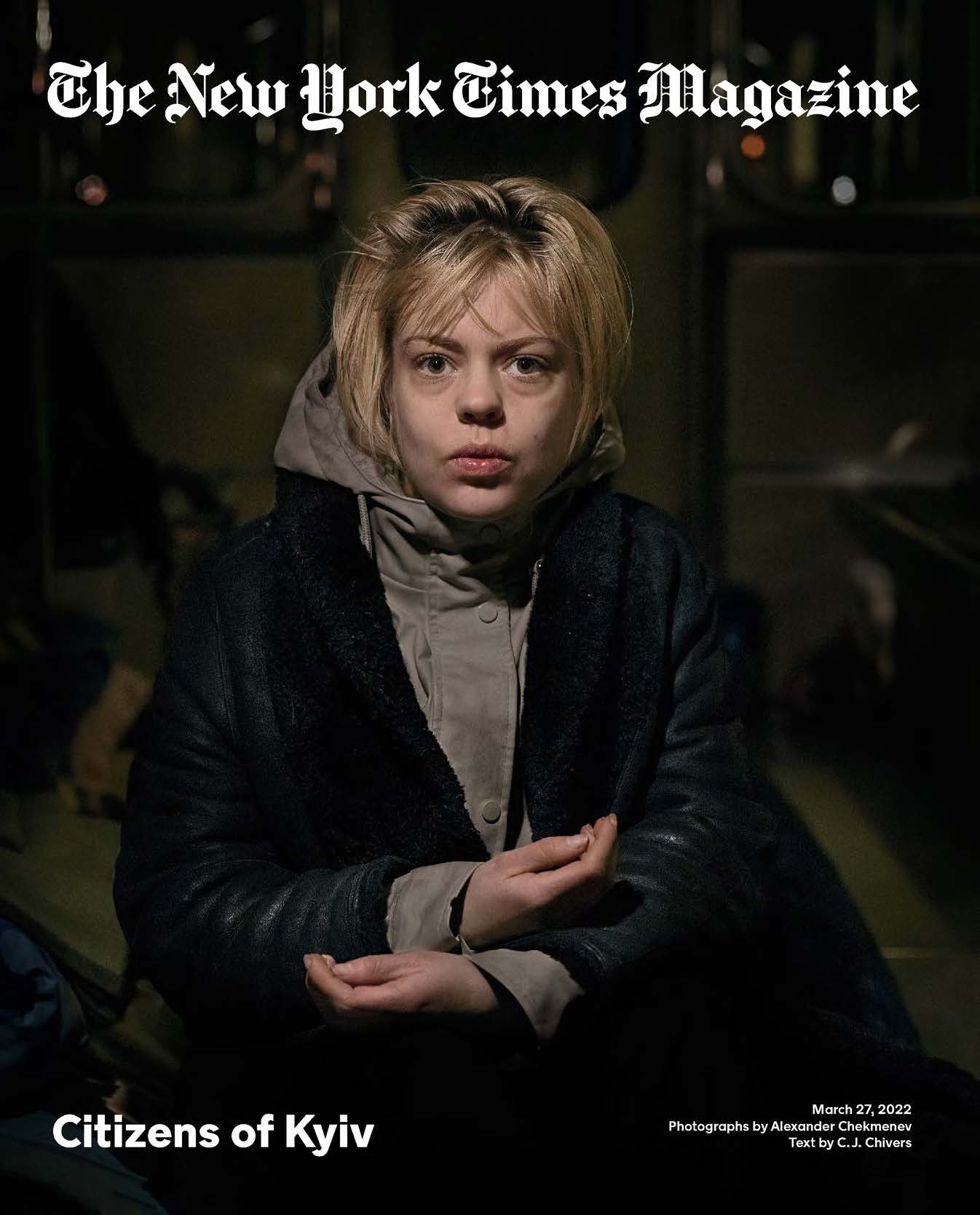

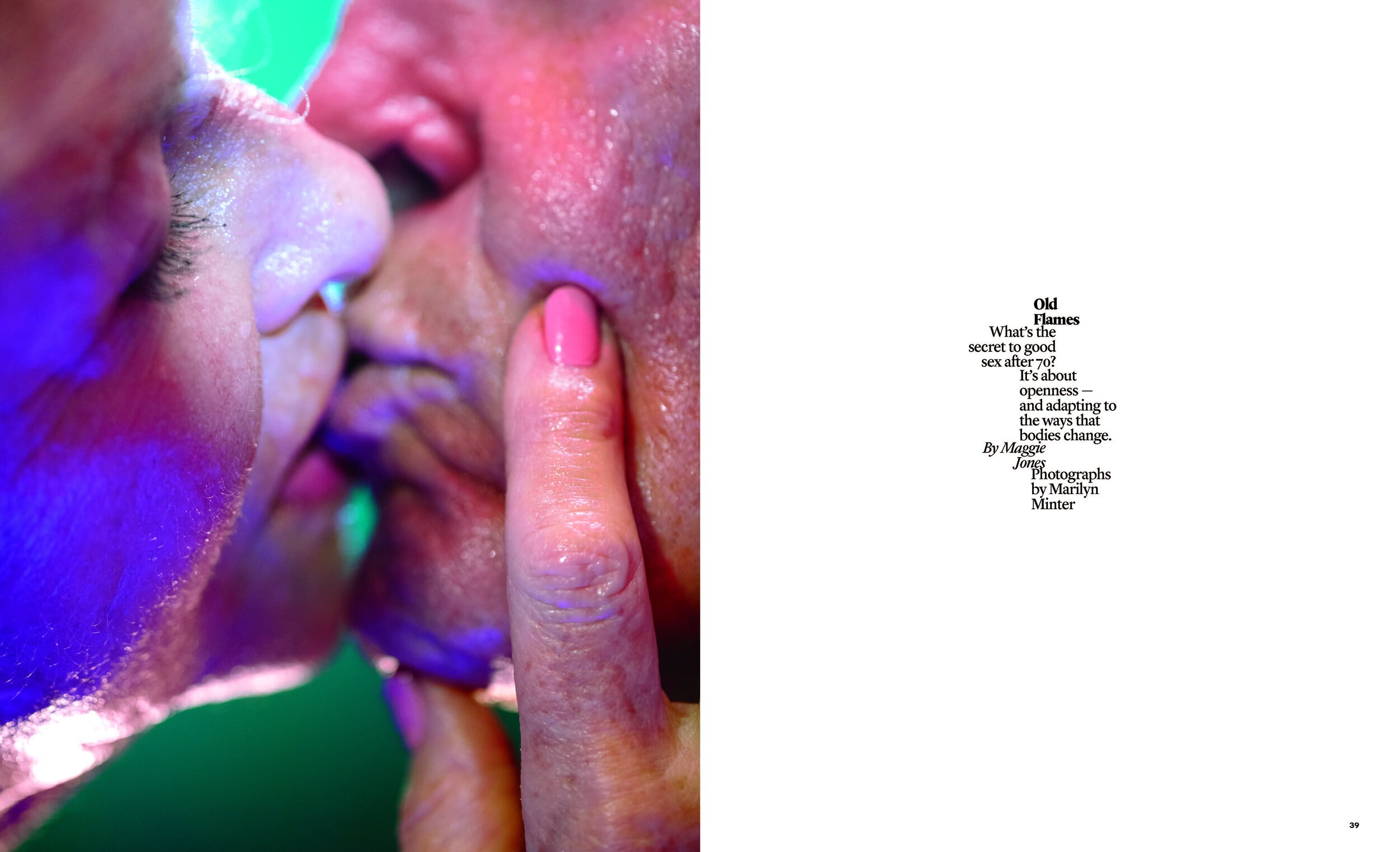

The Joys and Challenges of Sex After 70 Photographs by Marilyn Minter

George Gendron: I’m assuming that you must be willing to take certain kinds of risks with your cover. Can you think of a recent one where you and your team felt, “Okay, this is a risk, but this is a risk worth taking”?

Kathy Ryan: Yes. And you have to take risks, otherwise you won’t do something memorable, right? So often it’s when you take a risk that you make something that’s memorable.

I would say this year when we commissioned Marilyn Minter to do our cover story on sex after 70, there was a risk in that. And it was exciting. It was thrilling. Who knows what’s going to happen? Anytime you assign an artist—somebody like Marilyn Minter, who spends her time making her own artwork, marching to her own beat, coming up with her own thing she wants to do—it’s a little bit of a different thing than when you’re working with a magazine photographer who completely understands the rhythms.

But it was such a risk worth taking. Why? The subject itself is interesting. I think the headline was “The Joys and Challenges of Sex After 70.” And she’s a terrific artist who—it’s her territory. For years she’s been making work—early on feminists thought it was pornographic—but she always believed in a very liberated, free-spirited approach to sexuality and her artwork.

And I knew already from having worked with her before that she could rise to the occasion. She totally would. She’s just, she’s both the free-spirited, no-holds-barred, do-her-own-thing, artist. The rebel, as it were. And she also understands The New York Times. Like, going into it, that was the feeling.

And we had a lot of fun. David Carthas was the photo editor on the project and he produced the whole thing, which basically meant casting. We worked doing the casting of the people of a certain age, which was its own challenge. And then it was a couple days in the studio in New York with Marilyn and there was a risk. Who knows? Not only are we working with this artist, we’re working with people who are semi-nude. They’re in lingerie and, on the other hand, it was a high-impact cover. And I got a kick out of it because, when you look at the comments, there were people who loved it, loved it, and people who hated it.

And that’s an interesting place to be. How often do you do that with a magazine cover? It got a strong response. That’s the best. That’s the best, right? You know that from what you were just talking about—if you can take a risk like that, but of course you have to, especially at The New York Times, you have to do it in an intelligent way.

With this subject, it seemed like we could take that kind of risk. If we’re covering an extremely important, of-the-moment political story, that’s not a moment when you’re going to go and do something artsy, highly creative, risky, right? Because there’s certain other criteria we have to meet. That the cover needs to accomplish. And journalistically it goes into a different zone. But, we’re lucky enough that sometimes, after years of doing this, I have a sense of where there’s some latitude. And obviously, working with Jake and Gail and the team, Is this one where we can do something fun?

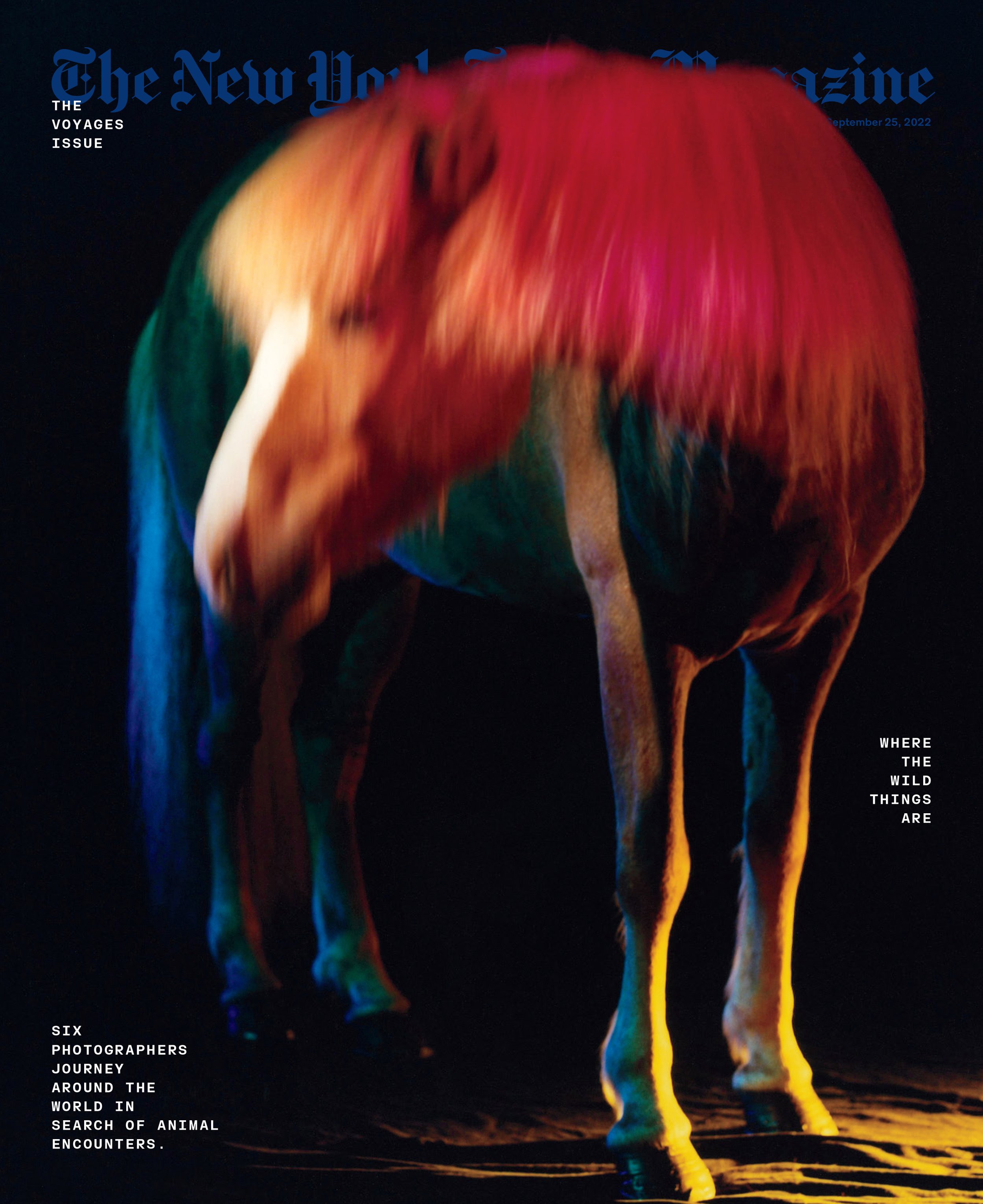

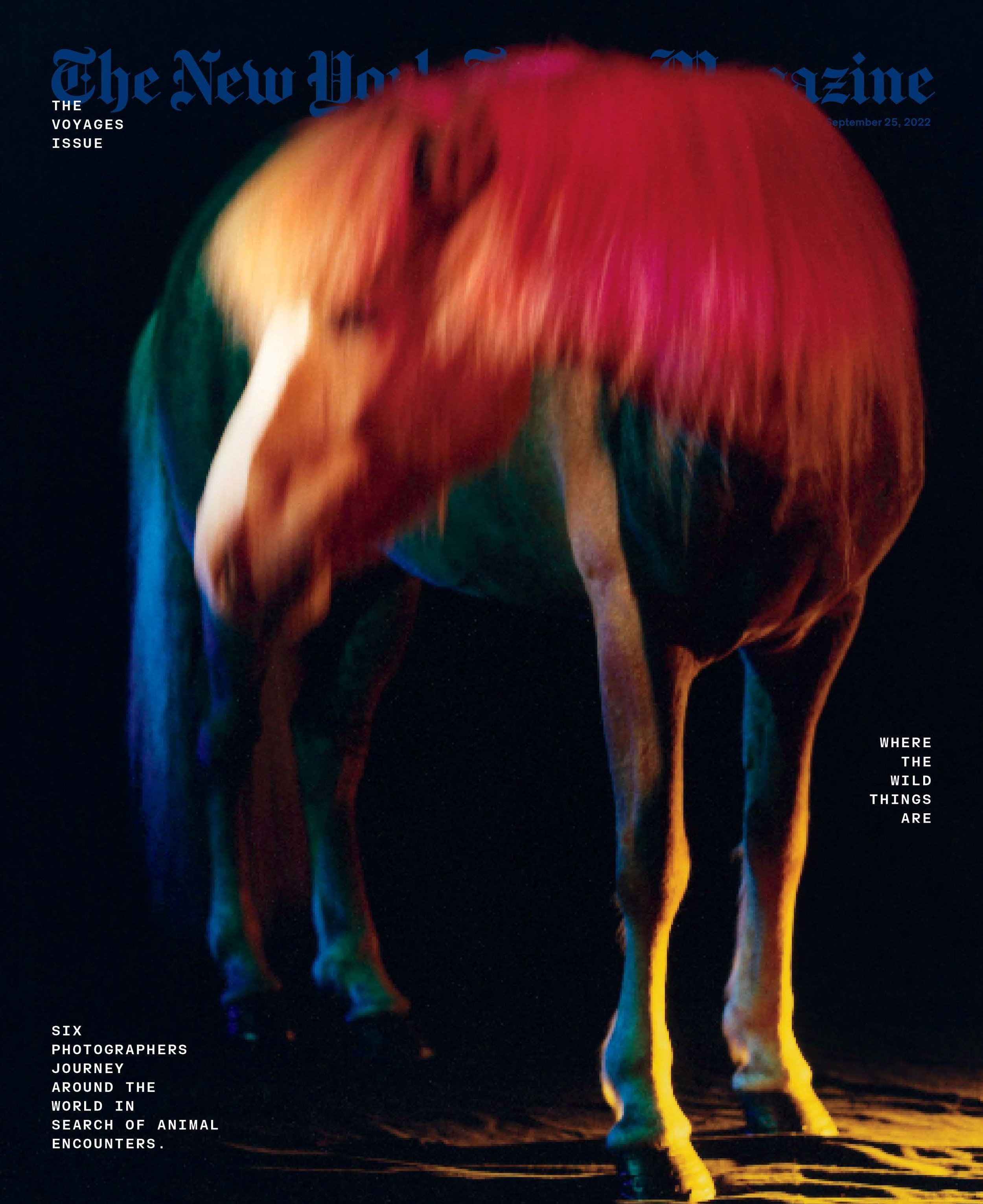

Every year we do a voyages photo issue, usually in the fall. And this year the theme for it was animals. And it was an idea that Amy Kellner, one of our picture editors had. She had been pitching doing animals for years.

And this was the year it got the green light. And this is always, for us, particularly exciting because the photo team gets to drive it to a large extent. And we started figuring out ideas along with story editors.

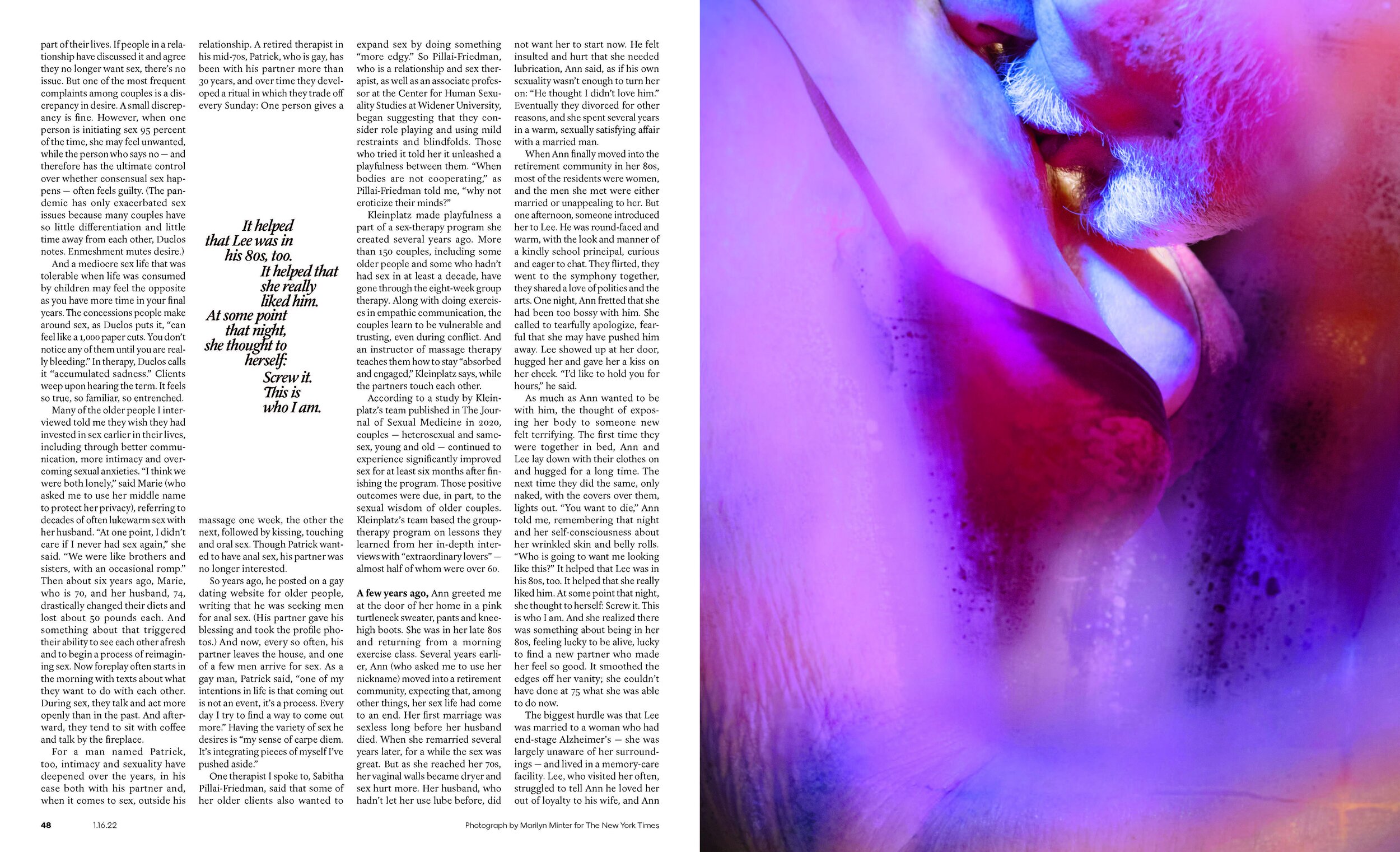

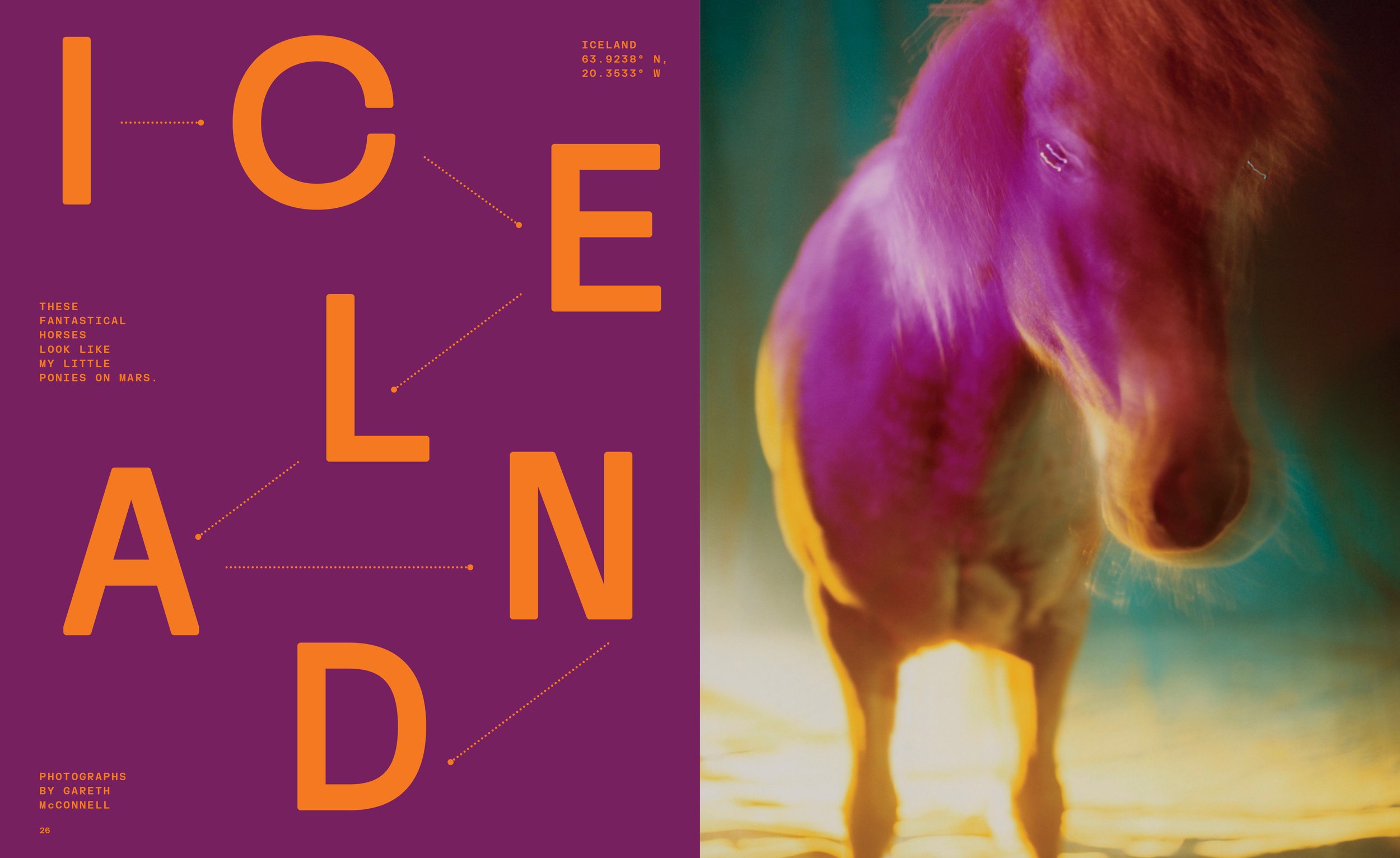

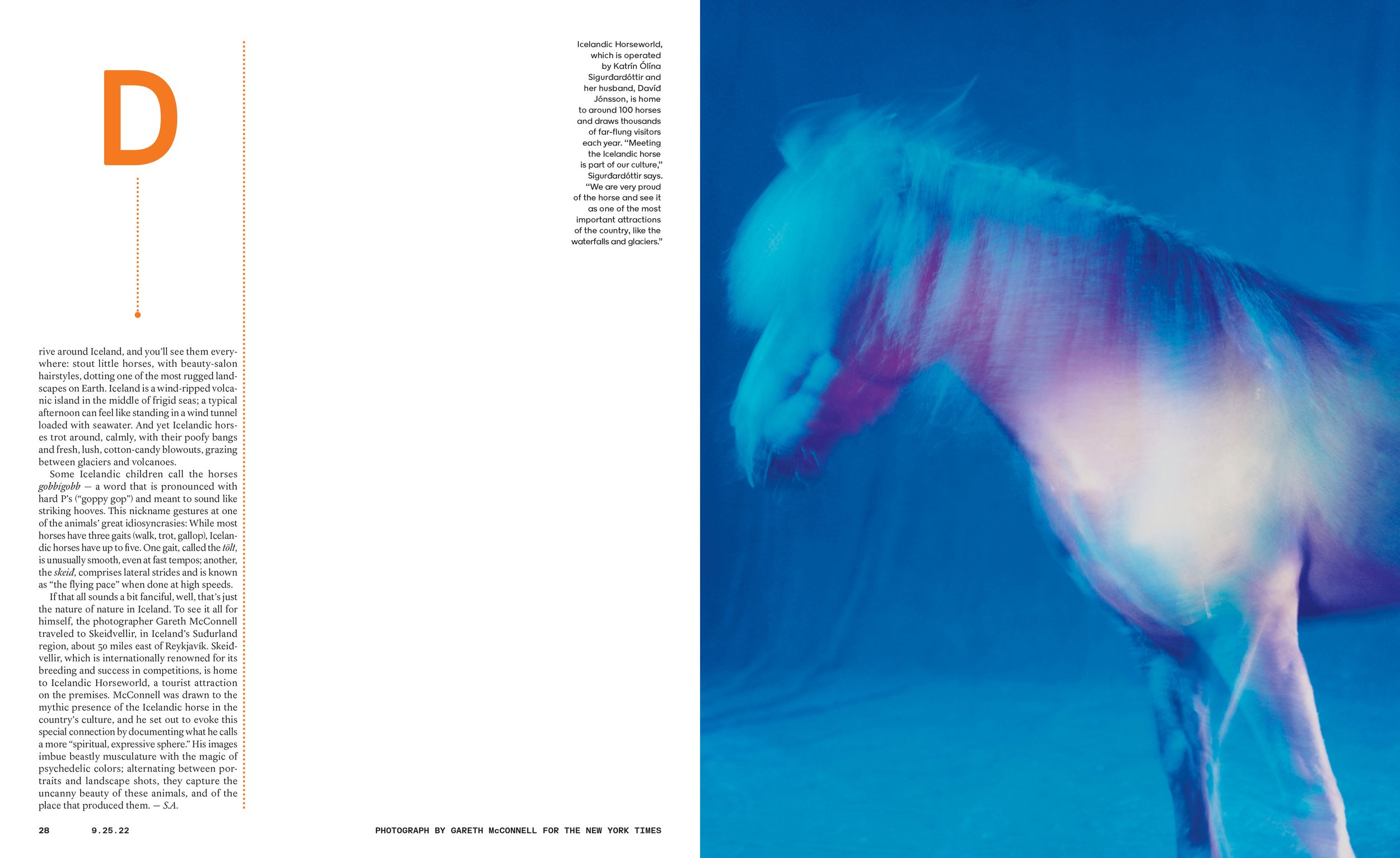

And one of the ideas that Sam Anderson, one of the writers, pitched was the Icelandic ponies. They have these funny small horses in Iceland that people love, and so that was one of the five or six photo essays that we commissioned. And I was thinking right away, Okay, if we’re going to do animals, we have to do something different.

“It all starts with somebody having the ability to compose the chaos of the world within the frame, the ability to see light. Because photography is always about light.”

So brainstorming with Amy, she said something like, “Maybe we should show them like they’re, like, My Little Pony Rainbow Ponies.” I was like, “Yes!” And then I thought of Gareth McConnell. A brilliant Irish photographer who does these fabulous—his pictures have an “otherness.” They breathe and shimmer with something else. Like he’s often doing still lives of flowers, his own personal work. They’re magnificent and there’s a shimmer to it, and the color comes out of darkness. Anyway, I could just imagine if we took him to those horses, he would do something magical.

In other words, it’s a way of saying his vision sees the magical and transcendent in the world. And we lined it all up. Rory Walsh on our staff and Jessica Dimson found the best horses in Iceland, worked the access to that, and then we worked with them to black out the whole stable.

So anyway, Gareth did brilliant pictures and one of his photos was ultimately the cover. And it was this fabulous multi-colored horse, slightly out of focus, coming out of darkness. That’s when I think we’re at our best, where it’s unexpected because instead of just seeing the beautiful, natural horse, we had a wonderful back and forth. And I just felt like, “Hey, this is a chance we can transform it into something.” So we love to do that, if we can.

George Gendron: It’s interesting listening to you talk because one of the things that people have said about the magazine, and you in particular, is that you seem to challenge the boundary between photojournalism and fine art in a way that I’m not sure magazines have very often.

Kathy Ryan: I think that’s right. It was something I picked up on early in my career. And I got very excited by that because it allows the magazine to look different, to do something unexpected. Artists sometimes tap into something. In portraiture, it’s an undercurrent of what somebody’s psychological being is. They sometimes have what I think of as a sixth sense, as do, sometimes, photojournalists.

Like sometimes an artist has developed a universe of imagery that works for us. And that’s what’s fun about it. Just knowing that. And then sometimes you can do the reverse, where you take someone pure documentary—years ago, I had Paolo Pellegrin do the Great Performers portfolio, all documentary, behind the scenes with the actors.

And that was just great because he would not normally be doing that. So he goes in there with a whole other frame of reference. The tricky thing is there’s certain stories that it works. Like you would not do that with a major conflict story obviously, or a major issue-oriented story.

Those are the moments when we would be talking about something entirely different where you have to work with seasoned pros, who know how to navigate that kind of heart-wrenching, difficult, dangerous story and make quick decisions in the field, and obviously, have vision. It all starts with somebody having the ability to compose the chaos of the world within the frame. The ability to see light. Because photography is always about light.

The Voyages Issue: Iceland Photographs by Gareth McConnell

George Gendron: I do have a question that builds right off of what you were just saying, and in fact, I was going to use Paolo as one of several examples. It’s the old Susan Sontag question. There’s work that he’s done—I think in his case it was particularly about immigrants—and work Gary Knight did during the early stages of the Iraq war. And the photos, when you saw them, were beautiful. They looked “renaissance” to use an Adam Moss adverb there. And so much so that—do you know Geoff Dyer, the British writer?

Kathy Ryan: Yes. I met him, but I don’t know him. No.

George Gendron: So in his book, See/Saw, he actually has a little mini-entry about conflict photography, and, under certain circumstances, its relationship with Renaissance painting. And he uses one of Knight’s photos, that can also be very wrenching, of a marine battalion, after one of the Marines has been killed in a mortar attack, as an example of this. And composition and lighting and tone. And so I’m curious about how you personally, as a director of photography, deal with that, because you’ve got these photographers who are just absolutely brilliant, and yet they are covering the horror of war, conflict, revolution. Now of course, the Ukraine invasion.

Kathy Ryan: Yep. Yep. It’s the hardest part of the job. And honestly, it’s harder as I get older. Somehow when I was younger and sending people into the field, of course I worried. Just the risk of it. I don’t actually even after all these years of working with Paolo Pellegrin—20 years we’ve worked together on many stories.

Working with Lynsey Addario. She’s extraordinary. She’s the most courageous person imaginable. She’s just unbelievable. I still don’t quite understand that level of courage, other than they’re driven. They’re both so driven, as are many other great photographers.

So if I can have the inner dialogue with myself that they have to do it, I would never call someone who’s never gone to cover that kind of story and say, “Hey, would you go do this?” I want to know somebody’s made that decision already. So Lynsey’s going to do it anyway. Paolo’s going to do it anyway.

It’s the title of her book, It’s What I Do. I can’t quite fathom it even after all this time. And then all the visual decision making that goes on as chaos is unfolding in front of them. When you speak about “Renaissance-esque,” there’s a picture Lynsey made years ago in Afghanistan on assignment for us, where she was on a patrol with the American soldiers and they were ambushed and one of them, Sergeant Rougle, was killed.

And the picture she made of his comrades, his friends who are just grief-stricken—it’s just happened—are taking his body down the muddy slope there. And she somehow gets into position. It looks like a religious painting. And she doesn’t think like that.

Lynsey’s not someone who’s, I think I can fairly say this, looking at classical art constantly to let that inform her thinking. It just came naturally in the way, I think, a great visual person sees. She’s more of a narrative storyteller. But it’s a haunting picture that went to that next level. It became something else.

And then Paolo—I’m not trying to compare, we're just talking about different approaches—overwhelmingly shoots in black and white. That right there is an abstraction. He has chosen that because black and white emphasizes emotion, eliminating unnecessary color. It gives him more of a chance to focus on composition. Composition becomes more important. And light.

Lynsey has consciously chosen in her career to photograph in color. And in her case, she doesn’t want the abstraction. And I don’t want to make sweeping statements for either of them, but I know them well enough. She wants to see all the reality that color gives you.

George Gendron: But then there’s also the issue for the director of photography about managing a certain tension between the aesthetics of a photo and the fact that the content of the photo is, in fact, conflict. Death and casualty. That’s got to be challenging.

Kathy Ryan: And it’s uncomfortable to talk about because with that kind of coverage the content rules. But still if you want to make a memorable picture, especially today with the abundance of imagery out there, you have to make something that is so well seen, so well composed or understood or framed, that it touches some other nerve. That stops people—making a haunting image. The aesthetics do matter.

“Photojournalists have to be opinionated. They have to take a stand. There has to be something that they care deeply about. And you have to have the courage to go for it.”

George Gendron: That gets into a question that someone who has had the arc of your career—you joined The New York Times in the late ’80s—and so you’ve done your job in an analog world and now you’re doing your job in a digital world. And it must be dramatically different as you try to conceptualize the visual solution to a story. When we’re living in this age of just over abundance of images. My God, you can’t get away from them.

Kathy Ryan: Yeah. It’s unbelievable. I feel like today it’s become way more challenging. When I started out, you turned to magazines and papers and books for the photos. That was it. And it’s just completely different. You know?

People have seen hundreds and hundreds of pictures every day. So where is our place in that? And I wish I had answers to some of that. I find it more and more challenging. And then there’s also the reality that there’s all sorts of creative work being posted on Instagram by non-professionals, like doing some just nifty stuff.

It opened up creativity in a lot of people. They couldn’t necessarily do a commissioned magazine assignment, but I see all sorts of just interesting creative material. And it’s just a different medium.

And that’s the other thing—every year we do an annual, “The Lives They Lived” issue. It’s the last issue of the year. And we do a series of stories about people who’ve died that year. And it’s almost always people of renown—who are known in some way. Sometimes ultra-famous, sometimes not ultra-famous, but known in their field. And this year, a decision was made by Jake to devote the whole issue to children killed by guns. And the reason for that was there’s been a shift.

Within the past year or two—the highest number of child mortality is related to gun deaths. So we’re in a terrible—we all know that. And there’s been just horrendous school shootings. So as we set out to figure out the art for that and the photography, the photo editor working on it, Kristen Geisler started calling all the families, which was a challenge unto itself because, of course, they were deeply grieving.

In some cases, she’s talking to the mother or the aunt or different family members. And we normally, in that issue, come up with a nice idea of something to commission. The year before we did the shoes of the people who died. And it was terrific. We had Eric Carle, the children’s book illustrator’s, paint-splattered shoes. We had the boots that Halyna Hutchins was wearing the day she was shot on the movie set where she was accidentally shot.

And we’ve done the empty rooms left behind by the deceased. But I decided, talking with Gail and Kristen and Jake, everybody, that this was a moment to use vernacular photography. We just illustrate it with the images that the family members themselves had. Which would basically mean smartphone photography, TikTok videos.

So Kristen started pulling in all that material. We were looking at it closely. And it was very challenging. It was emotionally wrenching, as you can imagine. It was one of the most emotionally-wrenching things we’ve done. The subject matter was so sad and we wanted to do right by these kids.

George Gendron: It was emotionally wrenching for readers!

Kathy Ryan: Yes. And we knew that. People are going to be devastated by it. And that is another responsibility for us at the magazine that we discussed a lot.

And then we were also working with tiny digital files. So you also need to figure out, How will this work? Where is our cover image? And then we decided to go right into it. And Gail and Matt Curtis, who was designing the issue with her, decided to do these double-truck [two-page spread] images of the faces blown up. So we were looking at that very closely, trying to figure that out.

And then the image that ultimately was on the cover—as soon as we saw that and it was backlit, everything about it was so pure. A professional wouldn’t have shot the picture that way with the light flooding from behind. But what it did was it gave it just a spiritual look.

And as soon as I saw that one in the cover mat, I felt, “There it is!” And then of course we all came to that conclusion, but we were nervous. It was a very different type of image. But Kristen was getting in these clips from the TikTok videos that she was looking at closely with the digital team. And when we published, the power of the short video clips eclipsed the power of the still photos. And you’re not going to hear me say that often, because I’m a diehard. I mean, I love video, but still photography has such a special place. And this was a case where just seeing the little bit of movement of the child had so much power.

And of course, these pictures were all made for just the most personal, pure, intimate reasons. And the brief for them was to not focus on the death at all, but just focus on a day in the kids’ lives. Something in the kids’ lives that was just about them, alive and happy.

And today, with the new medium that we have, most of our readers, the majority, are seeing us on their phone. That was very powerful on the phone as well as in print.

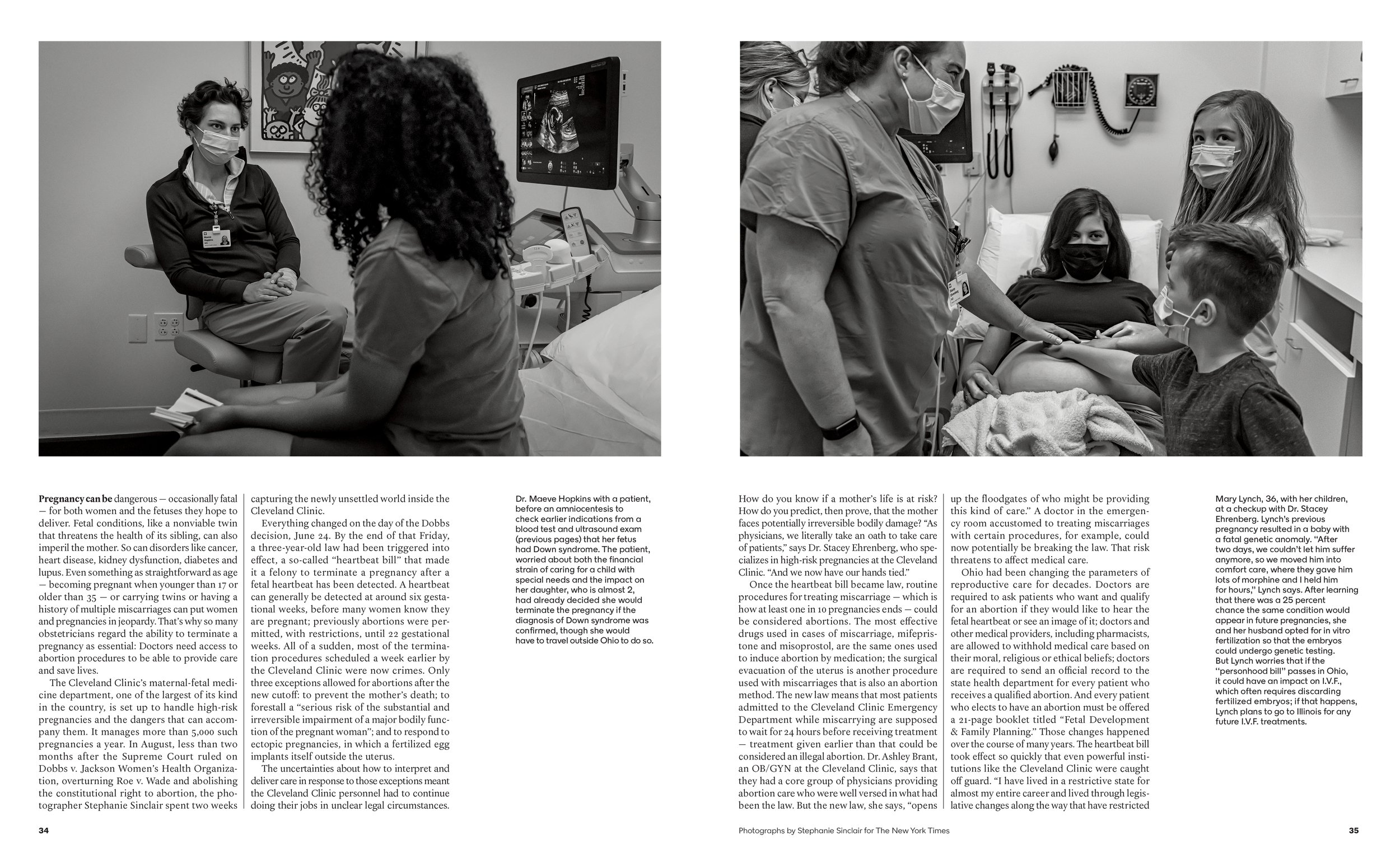

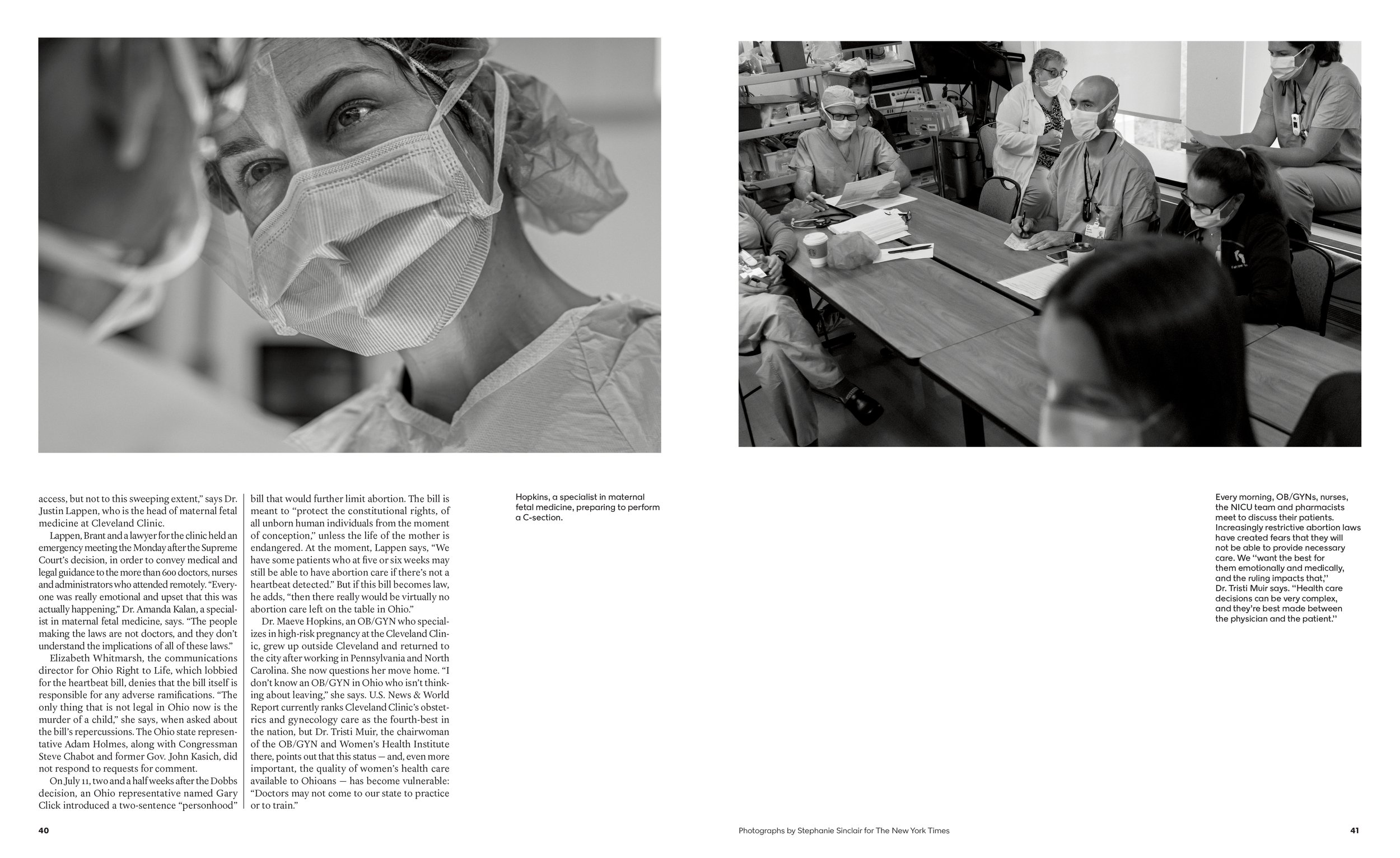

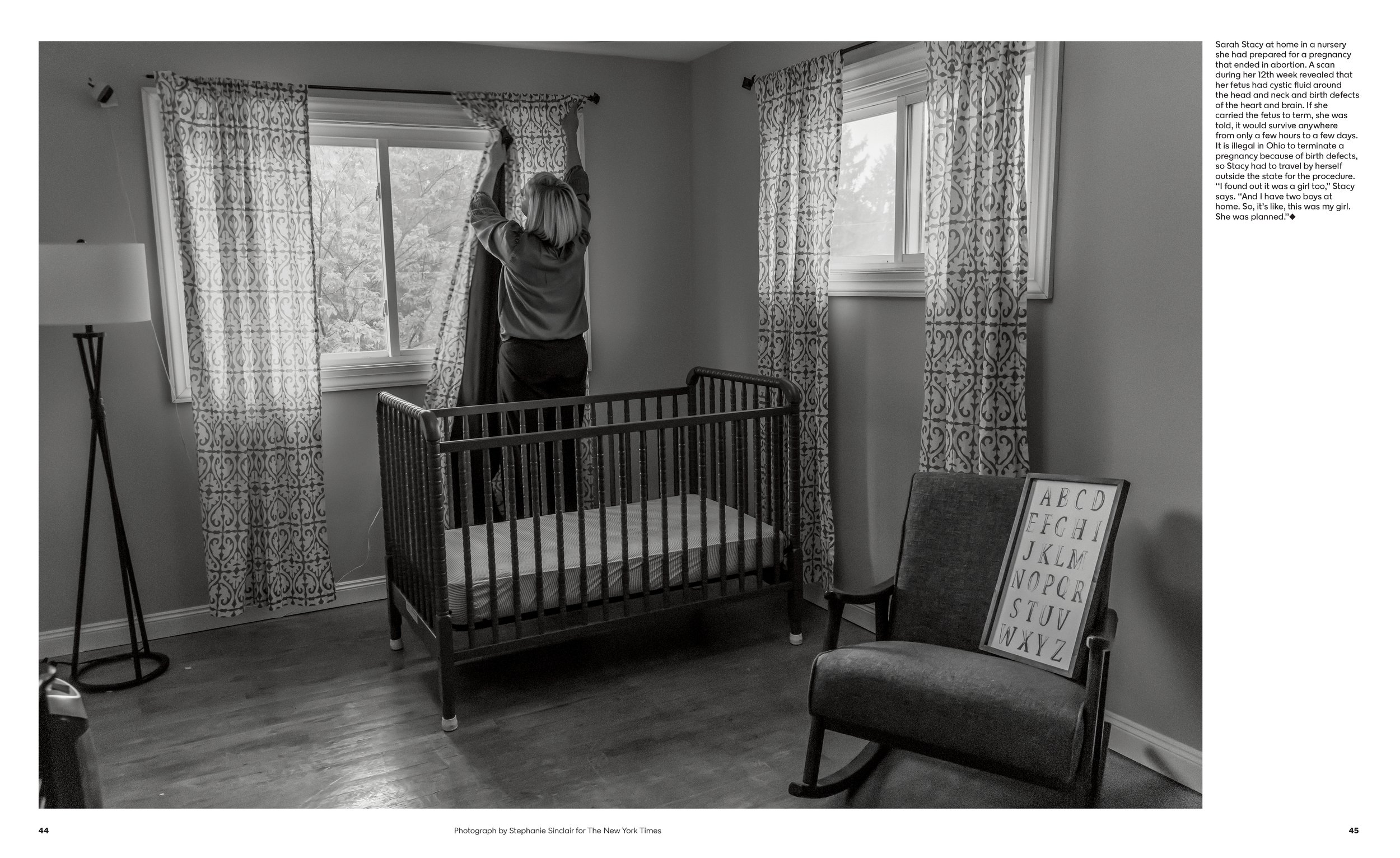

Lives on the Line: Patients with High-Risk Pregnancies Photographs by Stephanie Sinclair

George Gendron: Let’s go back to what you just said a minute ago. It’s an interesting transition point because you were talking about your passion for the photograph. Where did that come from? What did you want to be when you were 12 years old? Did you want to be a photo editor?

Kathy Ryan: I had no idea. I always liked to draw. I was a kid that always liked doing art. And I had an older sister, a year older, and she loved to draw. And we would draw for hours on end. My parents would buy discarded rolls of wallpaper where it was a buff on the back and they’d roll it out. So we had all that blank paper to keep drawing.

Ryan in the third grade

George Gendron: Did you grow up in New Jersey? Because we did that.

Kathy Ryan: Yes!

George Gendron: Did you really?

Kathy Ryan: Yeah. Where did you grow up In New jersey?

George Gendron: Up in Bergen County. I grew up in Oradell and New Milford.

Kathy Ryan: I grew up in Bound Brook. But there’s going to be another overlap because listening to your podcast, a pivotal moment for me was third grade, which I think was the case with you, right?

George Gendron: Yes.

Kathy Ryan: And so it’s a weird coincidence. In third grade, I had a teacher—I was in Catholic school at that point—Sister Mary William, a nun, and she taught art history. This was in a very strict, classic, traditional classroom. But once a week she passed out black and white marble notebooks, and she would pass out small reproductions of paintings, famous paintings, classical artwork. And we would paste them in while she talked about what the symbolism was in the painting, what the artist might be thinking, what the expression on the person’s face and the painting was. I fell in love with it. I just felt like, “I got it.” I so got it.

George Gendron: What was the “it” that you got?

Kathy Ryan: Just understanding. Looking at the pictures. I can’t explain it. It was like, “Wow, I get it!” Whereas, I’ll be honest, in music class I just didn’t get it. I couldn’t hear the different notes. But it was like I could see it.

George Gendron: The power of the visual.

Kathy Ryan: Yeah, the visual. I could see what she was talking about when she mentioned an expression. I could see it in the face or something symbolizing something else. It just kind of clicked. So throughout early schooling I was always drawing, painting, and making art. And then at the end of high school—I had interest also in politics because the Watergate hearings were on. So I went to Rutgers, Douglass College, with an idea toward majoring in art or potentially shifting to politics.

And then very quickly I focused on art, but not photography. My college studies were painting—I did lithography, I did a lot of printmaking. But never photography. And then when I got out of school, I realized very quickly after working for hours in the studio for several months, I don’t like being alone all day. I love working with people. It’s my nature. I wanted to work with the team.

And a friend of mine told me about an opening at a photo agency. It was called Sygma. As you know, one of the big photo news agencies in that era. Sygma, Gamma, Sipa, Magnum. And they needed a librarian to file—remember this was the days of slides, negatives, prints. There were no digital images. So everything existed as a physical object. And they had photographers all over the world that would send their work to the Paris bureau where they would process it all. They had the lab there and then shipped it to us in New York.

And I got hired as a librarian. So I would just figure it out, stamp the slides, and where to file them. Then I graduated to doing photo editing for The New York Times Magazine, when they would call and say, “We’re doing a story on Iran.” And I would put together a package for them of slides and prints related to that subject.

And then ultimately, when there was an opening, I applied. They knew about working with me because in those days they used more existing photography and less commissioned. So they were often calling Sygma. And initially I was doing a lot of painting at night but the more I worked in the field, I just fell more and more in love with photography and it made sense because there’s something “realer” about photography.

Like I often love when photography, as we were saying, goes to a more abstract, playful place. But I do like real. And sometimes I laugh looking back—when I was telling you about rolling out the wallpaper and my sister Maureen and I drawing—she would always want to draw the World’s Fair. And I always wanted to draw shopping at the supermarket. Because I knew shopping at the supermarket—what it looked like when mother would take us.

I liked to draw what I saw. And I sometimes think that The New York Times is the perfect place because in documentary we’re telling real stories.

George Gendron: It all comes together right now. Everything you’ve accomplished, everything you are today, Kathy Ryan, you owe to a Catholic nun.

Kathy Ryan: No, I don’t! I know, right? It’s funny how you get influenced. I know.

George Gendron: Yeah. That’s another podcast.

Kathy Ryan: Yeah, that’s another podcast.

Talk: Celebrity interviews from David Marchese Photographs by Mamadi Doumbouya

George Gendron: You are so obviously both passionate about photography and immersed in a world of the weekly, which is just so demanding. What do you do when you’re not working? Do you go to photo shows?

Kathy Ryan: I look at a lot of art—obviously photo shows. But just in the past month or two the stuff that had a big impact on me was at the Guggenheim, where there’s an amazing double-header right now. The Alex Katz exhibition of his paintings—which is a long lifetime of paintings and you watch the trajectory—is fantastic. And so for me to go see that opens up my mind in terms of photography. And they paired it with a big show of Nick Cave’s work, which is very sculptural.

So you’ve got the minimalism of Katz, and the spareness of it. And then you’ve got the maximalism of Cave and the political underpinnings—he’s taking on a whole other world of importance in what he’s trying to say in his work. And the first show I raced to go see was the big Hopper show at the Whitney, which, of course, is a crowd pleaser.

He’s over and over and over inspiring because, what did he paint? He painted light. He painted the loneliness of humans navigating the world. And photography, again and again, even in what I do as a weekly magazine picture editor is about light. How the photographers see light and have to think about people.

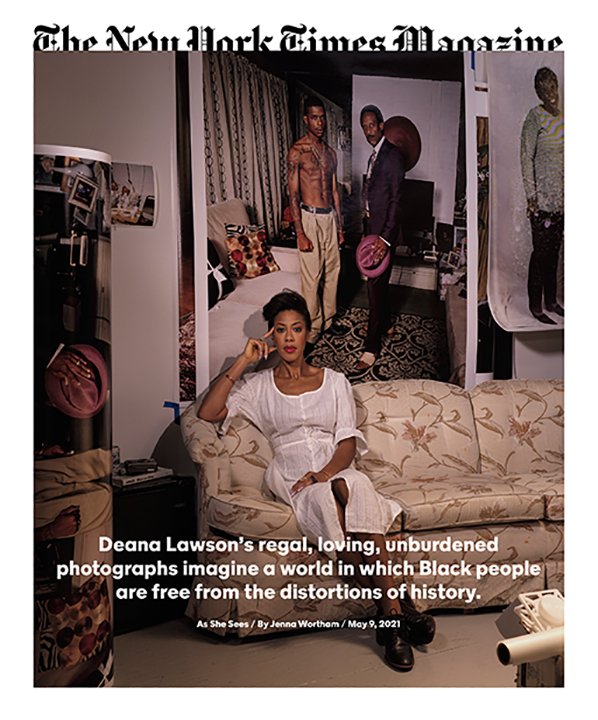

And Aperture has had so many exhibitions in the past that were huge eye-openers and just deeply inspiring. The show that they did a couple years ago, Antwaun Sargent curated, and was a book, The New Black Vanguard. Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant show. And walking through that, I immediately was introduced to the work of photographers I didn’t know, and it reinforced my appreciation of others.

And one of the people in that show, Arielle Bobb-Willis, I was just blown away. Early 20s, brilliant work where she sees color like nobody else and she has the figure, the human figure moves in space in a way that is unique and different. That’s not easy to do. And even her styling of the pictures. She’s since done two different special music issues for us. So sometimes it’s directly related to my role as a photo editor at the magazine.

Six years ago, I saw a show of NYC Salt, a high school after-school photography program. And I went to their end-of-the-year exhibition and saw amazing work by a photographer named Mamadi Doumbouya—at that point, maybe barely 20 years old—and just fell in love with it. And he’s been working with us since.

When we decided to do the David Marchese Talk column, we decided let’s have one photographer, one vision. Now, sometimes, it’s illustrated because it’s geographically not possible. But we’ve had Mamadi doing it since the start. And he has a very distinctive look, uniquely his. So going to exhibits and seeing constantly there are things to be discovered and then at other times seeing the work of great legendary painters where it just reinforces the quality of your seeing

That’s what I feel like. You know how some people go to exercise? I’m not too good on the exercise count, other than walking through museums. I go to exercise my brain. So I constantly regret that I don’t work out in a different way, but I feel like I work out my eyeballs a lot.

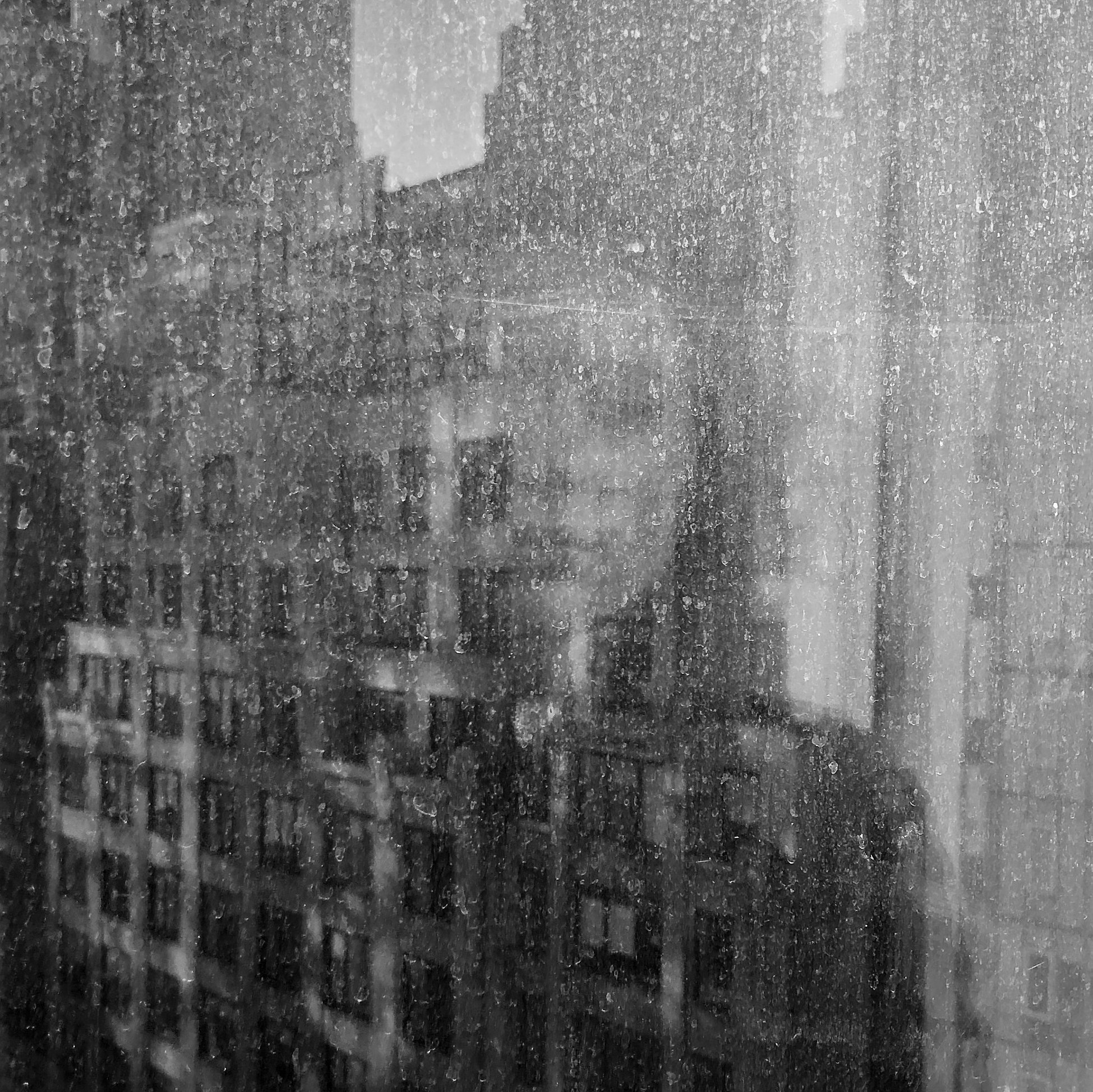

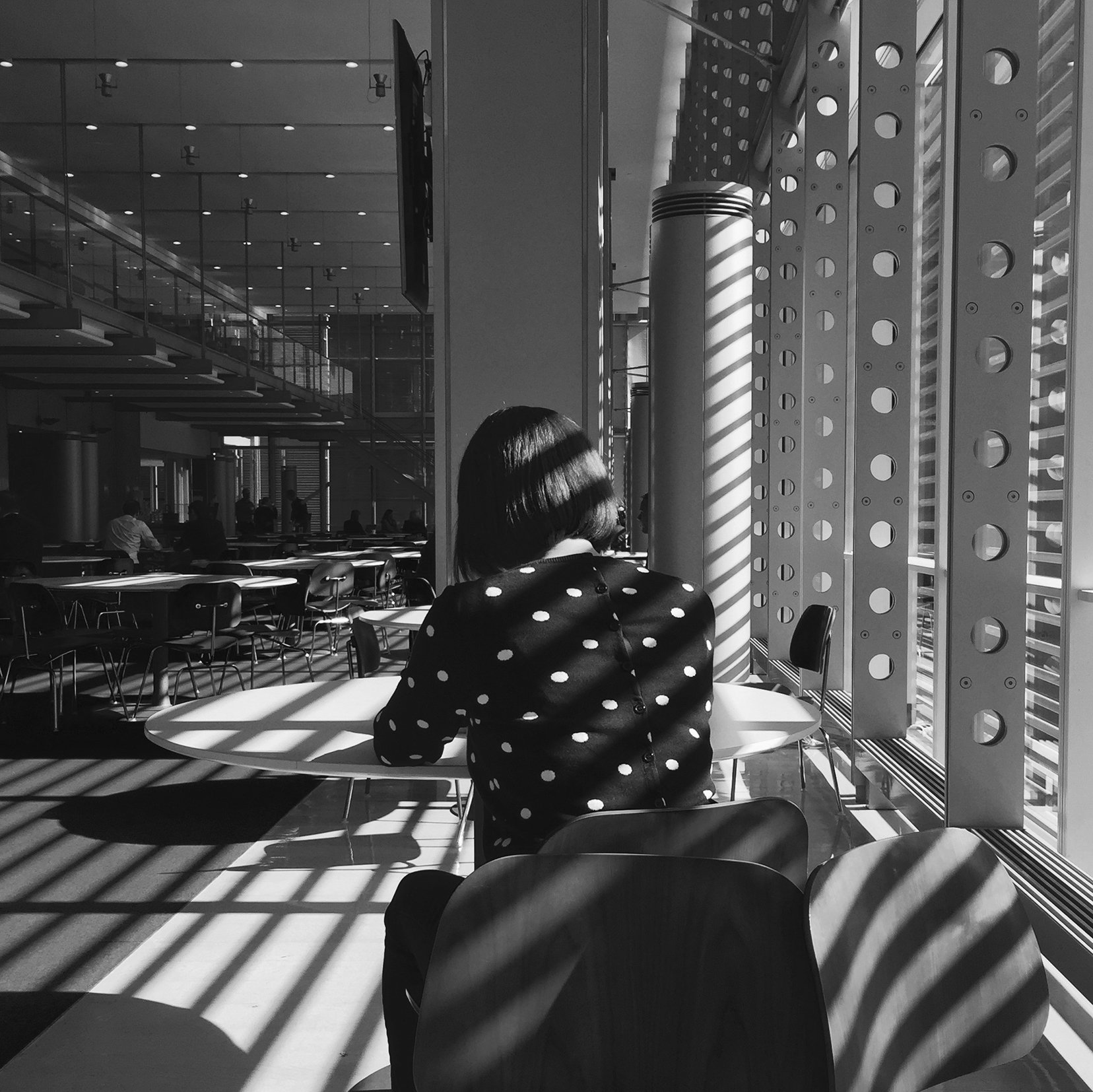

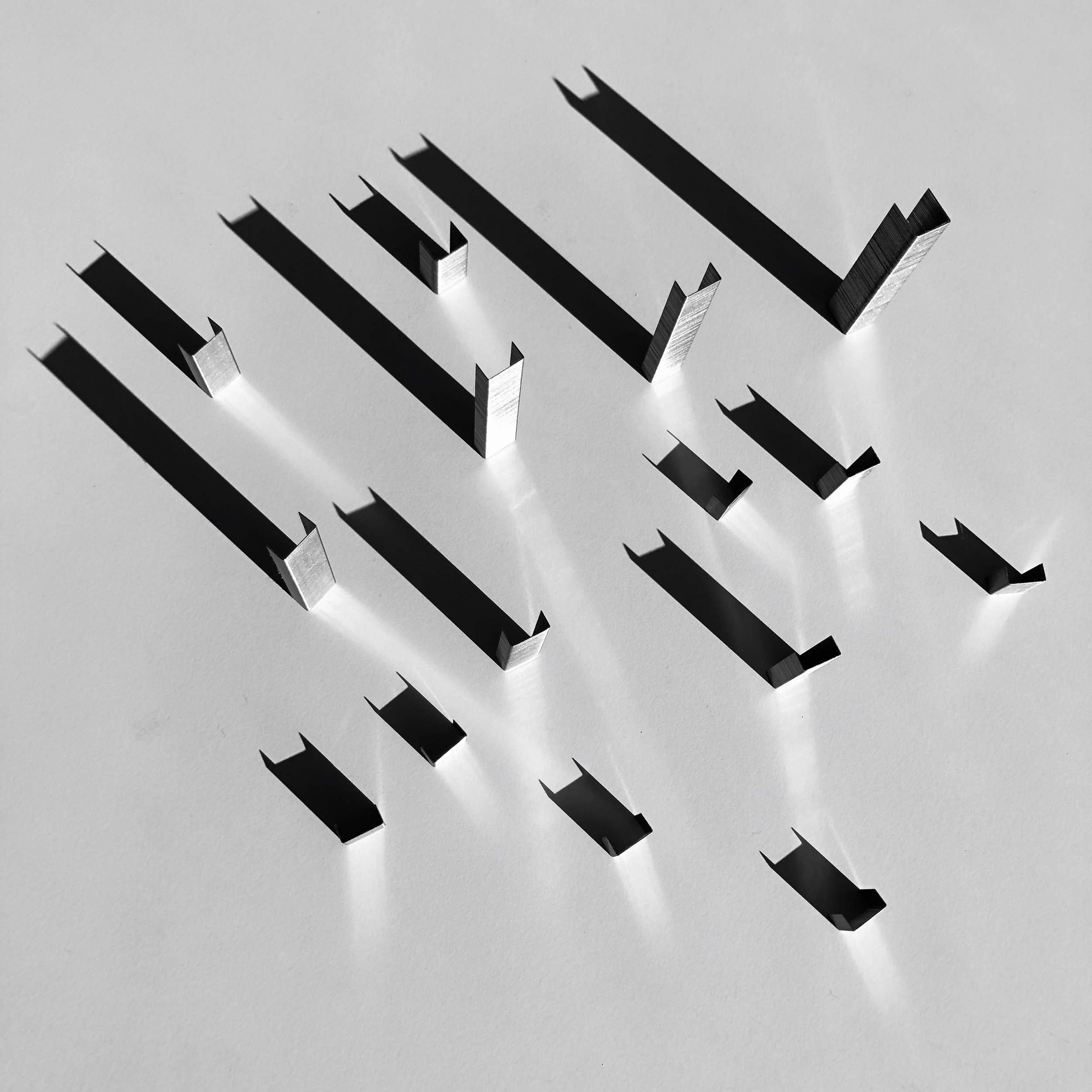

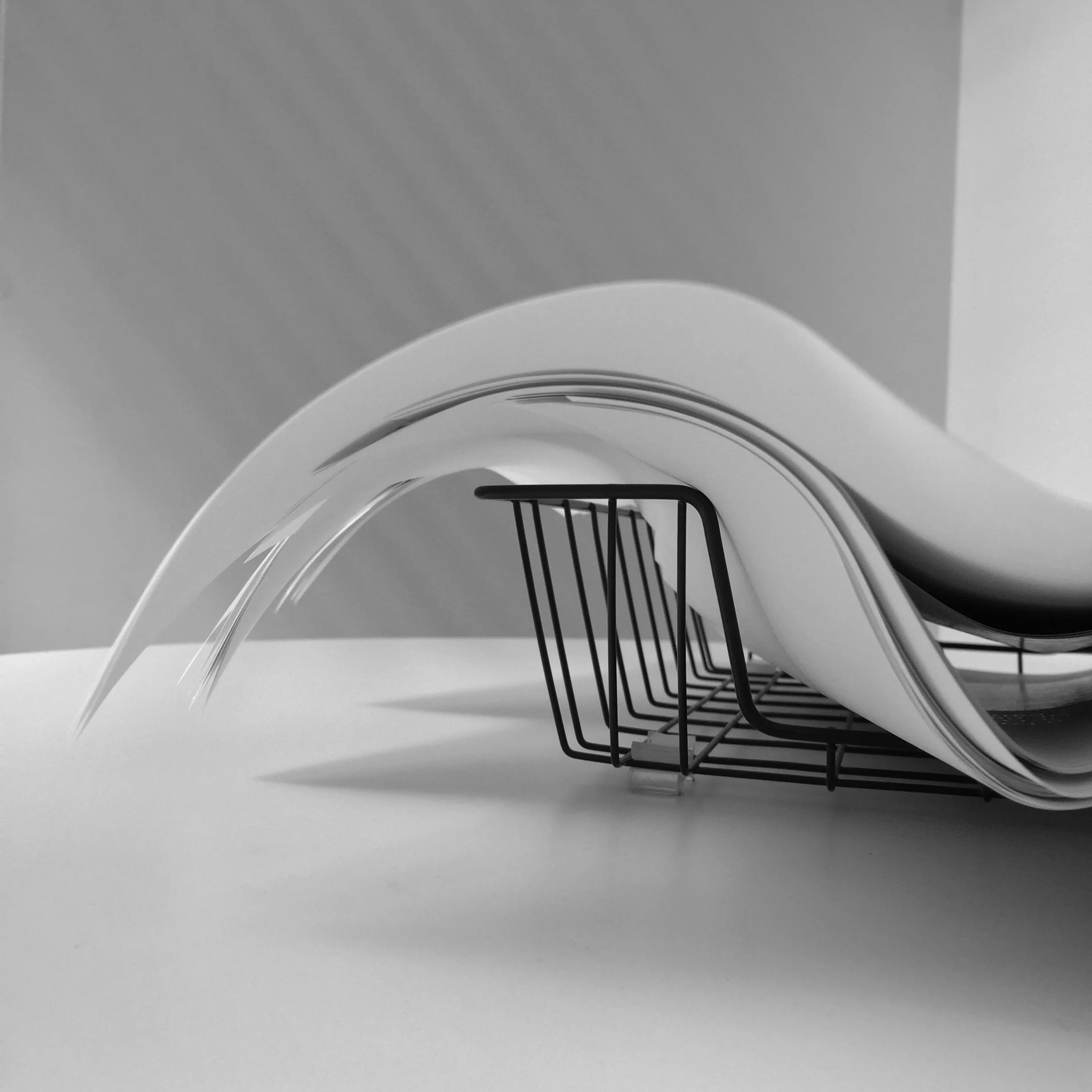

Office Romance Photographs by Kathy Ryan

George Gendron: That’s good enough. I can identify with that. I do want to pick up on your discussion about young artists, young photographers in a minute. But before we do, selfishly, I have to get you to talk about Office Romance, your book, which I have and I love, and I know lots of other people who have it. And everybody who has it, they just love to hold it.

The form factor, first of all, is great. And it inspires people to think about looking at the world around them—their house, the light around them—in a completely different way. And I’d love to know, at what point did you stop thinking about taking pictures of the new Times offices, designed by Renzo Piano, and posting them on Instagram, and start thinking about it as a potential book. And did that change your picture taking when you started to think, “Oh, this could be a book now’?

Kathy Ryan: That’s a very good question. And yes and I’ll tell you why. I started making the pictures just for pleasure. Literally, I just, I don’t know, I saw that bolt of light on the stairs one day and—you got the phone in your pocket, right?

So it’s right there, the camera’s in your pocket. And I took it out and I made a picture and it just felt so good. And then I made another, and I made another. And I was doing them at top speed. In between, you know, magazines are a frantic, kind of frenzied place. You know, we’re constantly on deadline.

There’s something deeply—stopping for a few seconds, in the same way somebody might have gone to get a cup of coffee in a cafeteria—I would just stop, make some pictures, take one of my coworkers, colleagues with me, friends. And, I don’t know, it was like a moment of respite and almost meditative. And part of the reason why and, honestly, all the credit goes to Renzo Piano.

The building, The New York Times Building, designed by Renzo Piano, has unbelievable light. Why does it have unbelievable light? It has clear glass windows! Almost no skyscrapers that get built today have clear glass windows. They all have to meet the environmental codes. The green glass, the gray glass, you see it.

He didn’t want to put “sunglasses on the building.” He didn’t want to do that. So he came up with the idea of the horizontal white ceramic rods that sheathe the whole building. And by doing that, he managed to meet the needs in terms of heat and light. The bars cut that down so that we are within the architectural regulations. Well, it creates unbelievably cinematic light, like film-noirish light. And it just kept calling to me. It was constantly calling out to me. It was literally like a siren’s call.

I’d see the light out of the corner of my eye and it was like, “Oh my God, I’ve got to photograph that.” So it’s also often just heartbreaking because for every time I’ve been able to do it, I’ve missed a bunch just due to what I do in my job.

And then somebody introduced me to Instagram. And I just was like, “Oh my God!” So you start posting. And when we first started posting, you’d be ecstatic if you got 50 followers. “Oh my God! Do you believe this?” At first it was just our friends. Like we were in that early. The whole thing seemed magical. And then people write nice comments. And that was helpful because I don’t think I would’ve had the guts.

The New York Times Building, designed by architect Renzo Piano, opened in 2007. (Photographs by Michel Denancé)

“It was breaking my heart during the pandemic—besides all this sadness with the pandemic—that I couldn’t be up in the building for a long time. It was very hard for me.”

I know that sounds weird for me to say that, but to put them out there—but then they were getting good feedback. And then I began to realize, “Wait a minute, I’ve got a subject here.” I just thought, “I’m going to call them #officeromance.” I wasn’t planning to do it, necessarily, as a series. But then it was becoming obvious. It’s a newsworthy building. In Times Square. In New York City, the greatest city in the world. It’s The New York Times, the greatest media company in the world. I’m lucky enough to work with all these amazing people I love, who I could photograph all day long. And I can put that work out there without invading privacy. I still have issues about how many private photos people put out. I didn’t want to be doing that. Everything I’ve ever posted, the subject is happy with. And it’s not that it’s a public place.

The hardest thing—or let’s say one of the most important things—a photographer can do is find a subject that others aren’t focusing on. If you embrace a subject that’s photographed all the time, the bar gets higher. If you choose a subject that's a natural fit for photography—and photographers for eons have gone down that road—if you choose to cover the same subject, you need to do something original with it.

And I mentioned Gareth McConnell earlier. He’s doing something with flowers that feels fresh and new to me and they’re amazing. The bar gets higher. You have to come up with something different. There are certain subjects, I don't understand why they're under-covered. One of them is work.

When you think about it, most people end up retiring from their jobs, not counting people like us, magazine people, but most people, and maybe not today, now that everybody’s got a phone, but even people with phones in their pocket, they don’t have pictures of themselves at work. They don’t. And I know a lot of the Office Romance photos I do are a moment to the side of work. They’re not pure documentary. We paused for a moment. The light is hitting the person. They’re bathing in it.

It just makes me sad. My father was a carpenter and a construction worker. I have no pictures of him at work. Do you know what I’d give to see one picture of him on the job? Just to see it? And so I just liked the idea that it’s more open territory. There’s an extraordinary body of work on office life by Lars Tunbjork, the great Swedish photographer who died about five or six years ago. Extraordinary.

They’re witty, they’re funny, they’re sad, they’re poignant. They’re everything. He touches a chord. That work is incredible. But there’re not that many bodies of work in office. I don’t have to compete. There’re far better photographers out there than me. Far better. Of course, we know that.

So at least I’m just doing something fun. Like, again, it’s mostly thanks to the light. And of course Manhattan has unbelievable light because we’re between two rivers. So the light reflecting off the rivers and that gets absorbed into the Times building.

George Gendron: I think people forget that about Manhattan.

Kathy Ryan: They forget that, right? They forget just how it’s clear and it’s cold, hard, crisp, light at certain times of the year. January, February. It’s amazing. And it was breaking my heart during the pandemic, besides all this sadness with the pandemic, that I couldn’t be up in the building for a long time. It was very hard for me.

But you asked how Office Romance got to be a book. At a certain point, I started, probably like all photographers, printing them out, looking at them and thinking, “Oh, this would be a great book.” And I just wanted to do a small book.

I showed them to Chris Boot, who was the director at Aperture at the time, and I had worked with him in the past on things. And I showed it and I asked if he’d be interested, and he said, “Yes!” right then and there. And we did it quickly. It’s a small, inexpensive book and it was literally pure pleasure. There was no stress.

Now the hard part comes, as all photographers know. The more you do this, the more you are raising a bar for yourself, and now I want to do a second book. And I have enormous self-doubt. I have been working on the book—nobody's seen it except my husband and our daughter and a couple other people. But due to my magazine schedule, I only work on the book in fits and starts.

There have been certain periods where I’ve gotten foamcore boards and I put the work up, and I thought I had a book and then I backed off it. And then I’m not sure that’s the way to do it. And then I struck the boards. And for months my magazine work kept me so busy I couldn’t focus on the book even on Saturdays and Sundays—the only time I can work on it—because it’s seven days a week as a photo editor. Then I would start up again.

Anyway, I want to do Office Romance II, and I’ve got a lot of pictures. I just far more afraid of it now, and unable to—I can’t explain it—I can’t seem to decide when’s the moment that I’ve landed on the right approach.

The New York Times Magazine Photography Team Photographs by Kathy Ryan

George Gendron: I understand that. One of the things that Adam Moss and I talked about when we did our podcast, was when he announced that he was going to retire, step down from New York magazine, he said, “Look, I’ve been working full throttle.” I think that’s the phrase he used. “I need to decompress.” When I was talking to people who knew Adam, I said, “How do you think he’s decompressing?” And everybody said the same thing: “Well, he’s painting. Very badly.”

So I said that to him and he said, “Oh, that’s absolutely true. I’m a tenth-rate painter.” But he made the point that he doesn’t aspire to the same level of excellence in painting that he felt he attained in magazine work. And as a result of that he just loves the process of painting for its own sake. And I understand what you’re saying because suddenly what was—think of it as an accidental project, right? Office Romance number one: it evolves organically, you’re doing it for yourself, you’re posting it on Instagram, you have conversations back and forth, a dialogue. Suddenly it becomes a book. And now it’s a book with a capital B.

Kathy Ryan: I know. Then it’s something else.

George Gendron: And you’re a photo editor and you’re working with some of the best photographers in the world. You’d better be good.

Kathy Ryan: I hear you. But again, it was one of the joys of iPhone photography. It removed some of that burden of “it better be good.” Do I want it to be good? Of course. I work hard. You’d be amazed how many frames I’ll shoot of one thing, trying to get it exactly, precisely how I want it to look.

George Gendron: I know what you mean though. You’re not running around with a Hasselblad.

Kathy Ryan: Yeah. But then, I don’t know, it's just, there was something so informal about it. I was never afraid of putting them out there. I can’t explain it. I just posted them, and if you like them, great. If you don’t—it removes a little bit of that pressure. So I was able to organically go into it in a kind of fearless way. This is just fun, and I love this building. I love the people I work with. And I’m grateful.

At one point after I’ve been doing Office Romance for quite a while, and even after the book was published, Jake said to me—we were undergoing a bit of a redesign—he said “I want to do something different on the contributors page. I’d like to have a portrait of a contributor each week.” It’s usually a writer, sometimes a photographer, sometimes an illustrator. And he said, “I’d like you to do it in the Office Romance style.” And first I was like, “Jake, you’re crazy because that’s now an assignment!” Like I just thought, “Oh, that’s the craziest idea ever.” I was terrified of that. And I’m like, “I don’t know if I can rise to that occasion.”

But I took the challenge and it was great. I loved it. I got to meet writers I might not meet in person otherwise. It also taught me, as a photo editor, I understand the photographic process so much more now having done that. What happens between photographer and subject. The role of power. The photographer versus the subject. The importance of eye contact. Now that I do the contributor photos, it opened up my mind and really taught me a couple things that have helped in the assigning.

So I was grateful to Jake. It was a gigantic new challenge. And trying to cram that in with everything I was doing. And I’m grateful now I have those pictures. That’s the other thing in photography, if you put the energy in it, then you have the pictures.

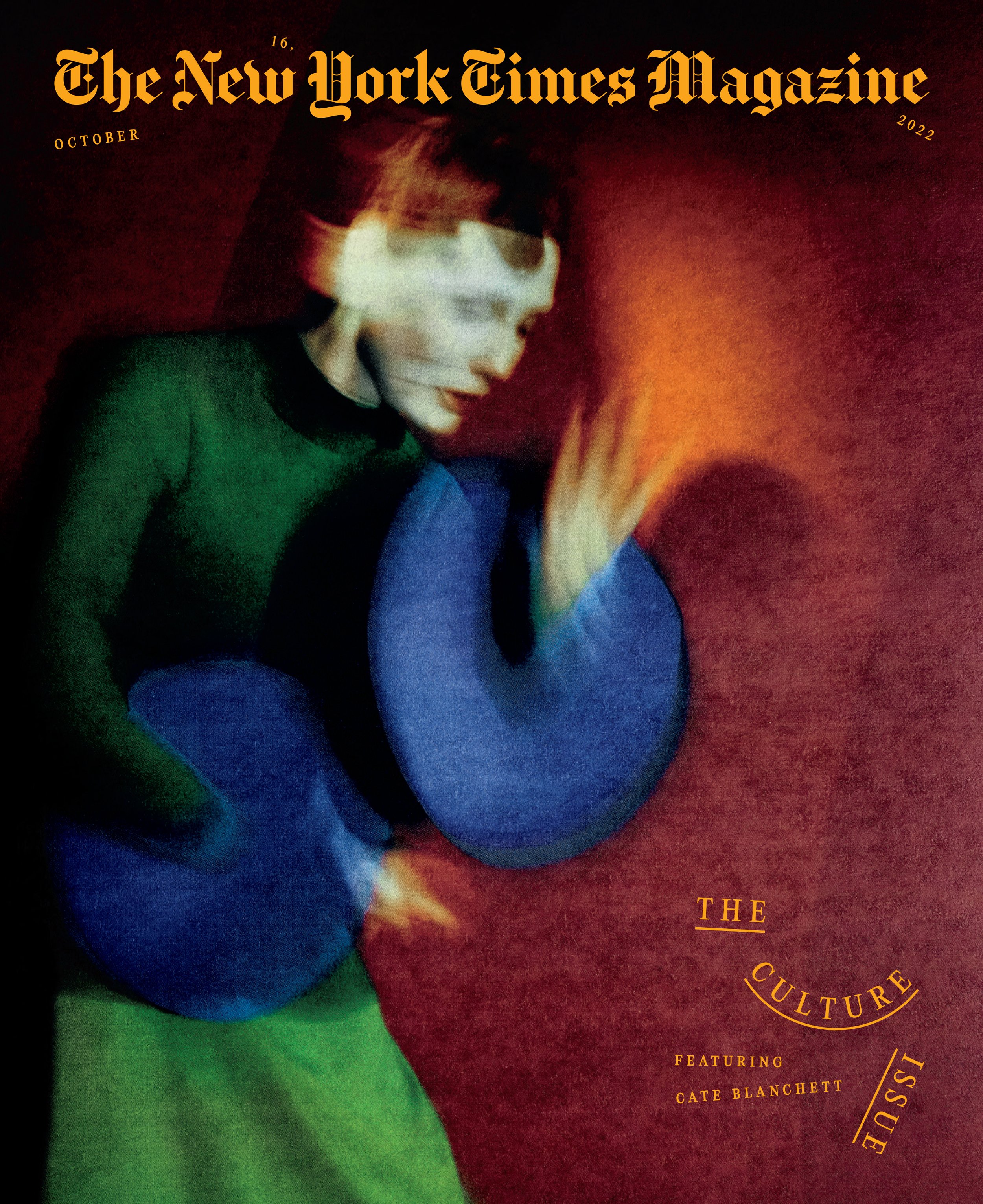

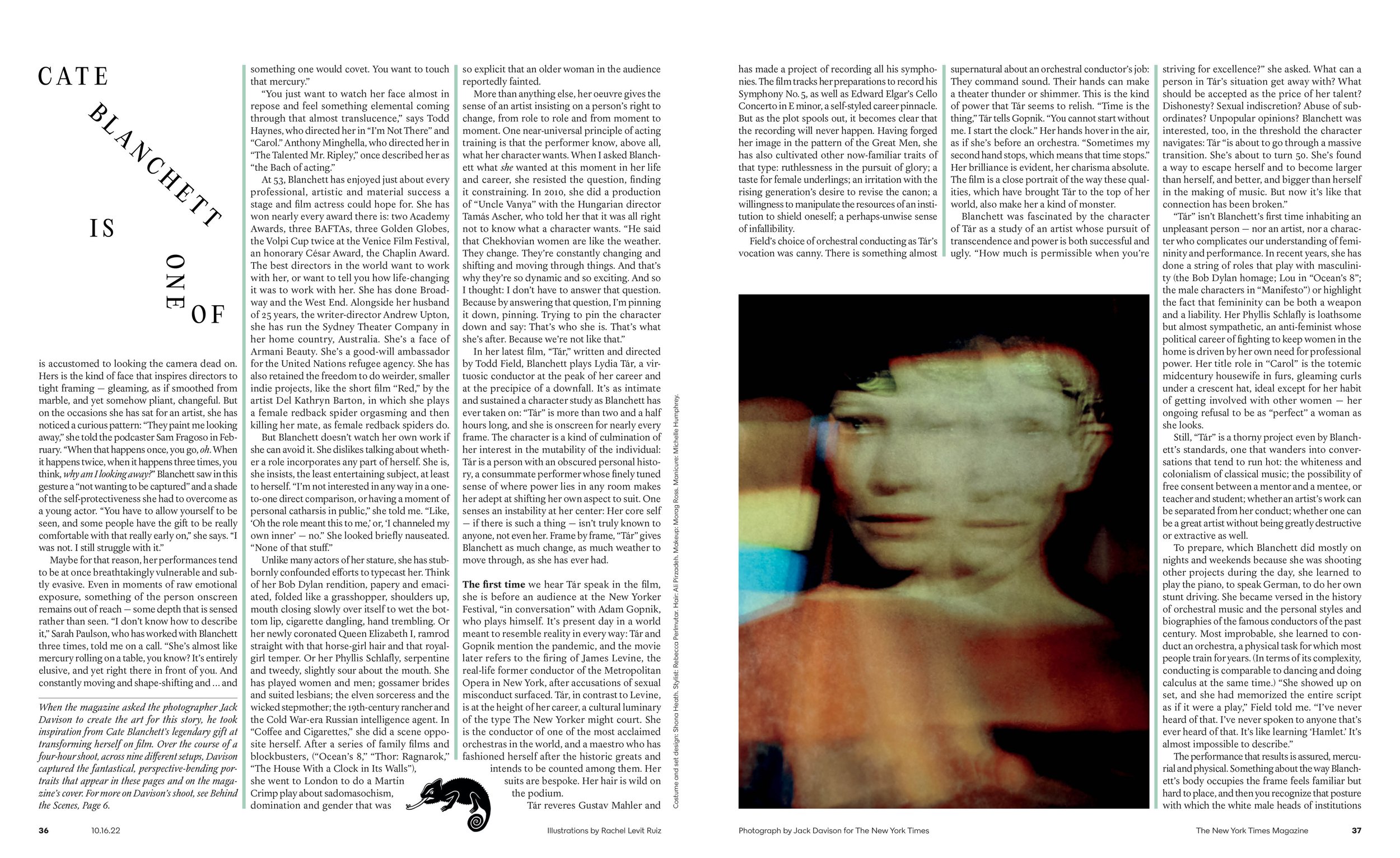

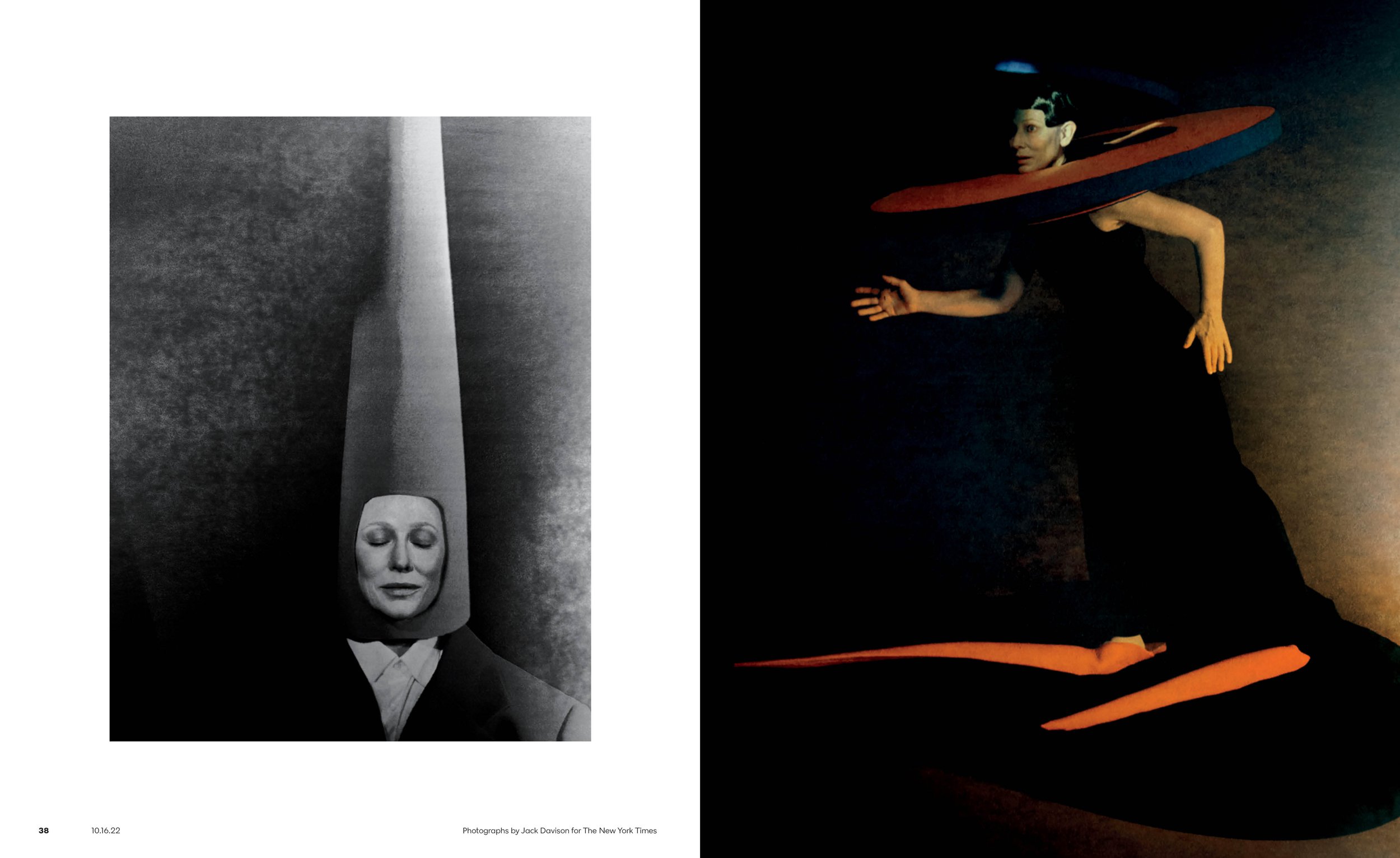

The Culture Issue, featuring Cate Blanchett Photographs by Jack Davison

George Gendron: Have you gotten a call from Apple yet?

Kathy Ryan: What about?

George Gendron: Well, if Steve Jobs or Johnny Ive were still there, they’d be on the phone with you right now saying, “We’ve got to figure out how to collaborate here.”

Kathy Ryan: Well, you know, I’ve got my good friend, Rem Duplessis there. And Stacey Baker. Brilliant Stacey Baker, who was one of our photo editors. And Najeebah Al-Ghadban, who was one of our great designers, is there. And Marvin Orellana, who worked as a photo editor at the magazine, is there.

George Gendron: We’ve taken a lot of your time, but I have to come back to one thing, which is that you’ve been talking a lot recently about young photographers. A young photographer in particular. And yet on the one hand, we live in this age where everybody has access to all sorts of different platforms. And can be inspired to pursue creative projects. And yet it seems as if younger people coming up wanting to be journalists, writers, editors, photographers, videographers have a more daunting challenge than ever before.

And so I’m curious if you were in front of young students at an art college who are there because they want to hear what you have to say. What advice do you give to younger people who want to pursue a career in photojournalism? What do you say to them?

Kathy Ryan: The first thing I would say is follow your heart. Follow what you think is important. Photojournalists have to be opinionated. They have to take a stand. There has to be something that they care deeply about. And you have to have the courage to go for it.

George Gendron: Are you talking about subject matter or point of view or all of the above?

Kathy Ryan: Now I’m talking more about subject matter. So for example, Stephanie Sinclair, a brilliant photographer, early on started working for the magazine. She did incredible work on child marriage and she was the first photojournalist, as far as I know, to ring the alarm bell that there’s child marriage in so many places in the world, particularly Afghanistan.

We’re now going back 15 years, whatever. She cared so deeply about that subject that she committed her life to it. She obviously trained and developed her eye. She made remarkable pictures. So a young photographer needs to figure out what a photojournalist needs to figure out what do they care about. And then they have to go after it.

If you’re going to be a photojournalist, you need to actually start to develop something that’s yours. And then that leads to other things, like in the case of Stephanie. Then after that, she started talking about genital cutting. In many cultures in the world that still happens.

“It was one of the joys of iPhone photography. It removed some of that burden of ‘it better be good.’ Do I want it to be good? Of course. I work hard. You’d be amazed how many frames I’ll shoot of one thing, trying to get it exactly, precisely how I want it to look. ”

So she did an extraordinary photo essay for us on the brides in Afghanistan. And then she went on and did a photo essay on a cutting ceremony. And then she proposed doing something on underage marriage within the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And that will take you through your career.

So her deep empathy and concern for subjects affecting girls and women, particularly girls in the world, it’s like you have to almost be a visual activist. And she actually became an activist.

Earlier this year, when the draft of the Dobbs vs. Jackson decision was leaked in May, Jake wanted to do something related to that. And Jessica Dimson, the deputy director of photography of the magazine, had the idea to do something on the Cleveland Clinic maternal health clinic where pregnant women go who have risky pregnancies. And for years, doctors have had, as one of their things they can use in the treatment if there’s risk, the possibility of ending the pregnancy, which then suddenly, when the Supreme Court ruled, was no longer the case.

And I suggested we assign Stephanie. And knowing this lifetime of commitment, she was able to walk into the room with those women under duress, their husbands, their doctors. Maybe they’ve gotten news that’s disturbing. They’re making extremely personal decisions.

I think for young photojournalists, entering, as you’re right to ask, a very difficult field. It’s difficult to make a living, and difficult to compete with the abundance of imagery out there. But there are subjects that are under-covered. And if they can find one, if there’s something they care about, that will fuel them. That will keep them driven in a way.

Patrick Mitchell: I have sort of a cynical follow up to that question, now that we’re in 2023. And that’s, is there such a thing as a career in photojournalism, now and moving forward? And what does it look like?

Kathy Ryan: Oh, I think there's definitely a career because we're a visual society, so even though there are a lot of pictures, we still need someone to sort out what's unfolding out there to make smart, informative, focused pictures to tell you how to look at things. I think of people—Philip Montgomery, Mark Peterson—they’ve been at it for years. They’re still so impassioned that between jumping on a plane for self-driven assignments, or for us, or for the paper, or for other magazines, there are stories that actually need to be told by people who can make the complicated images they do.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, same thing. She does her own artwork, but they’re real documentary images. They’re real documentary portraits. Her approach is a little bit of a different approach.

You know, just because everybody has a pencil doesn’t mean they can write. Just because everyone’s making phone photography doesn’t mean they’re making the kind of pictures that merit a million people looking at them and then coming away with an understanding that a great photographer can bring to a subject matter.

George Gendron: One last question for you. Have you ever been bored in your job?

Kathy Ryan: No. No. I’ve never been bored. No, there’s never been a day where I’m bored. That does not happen.

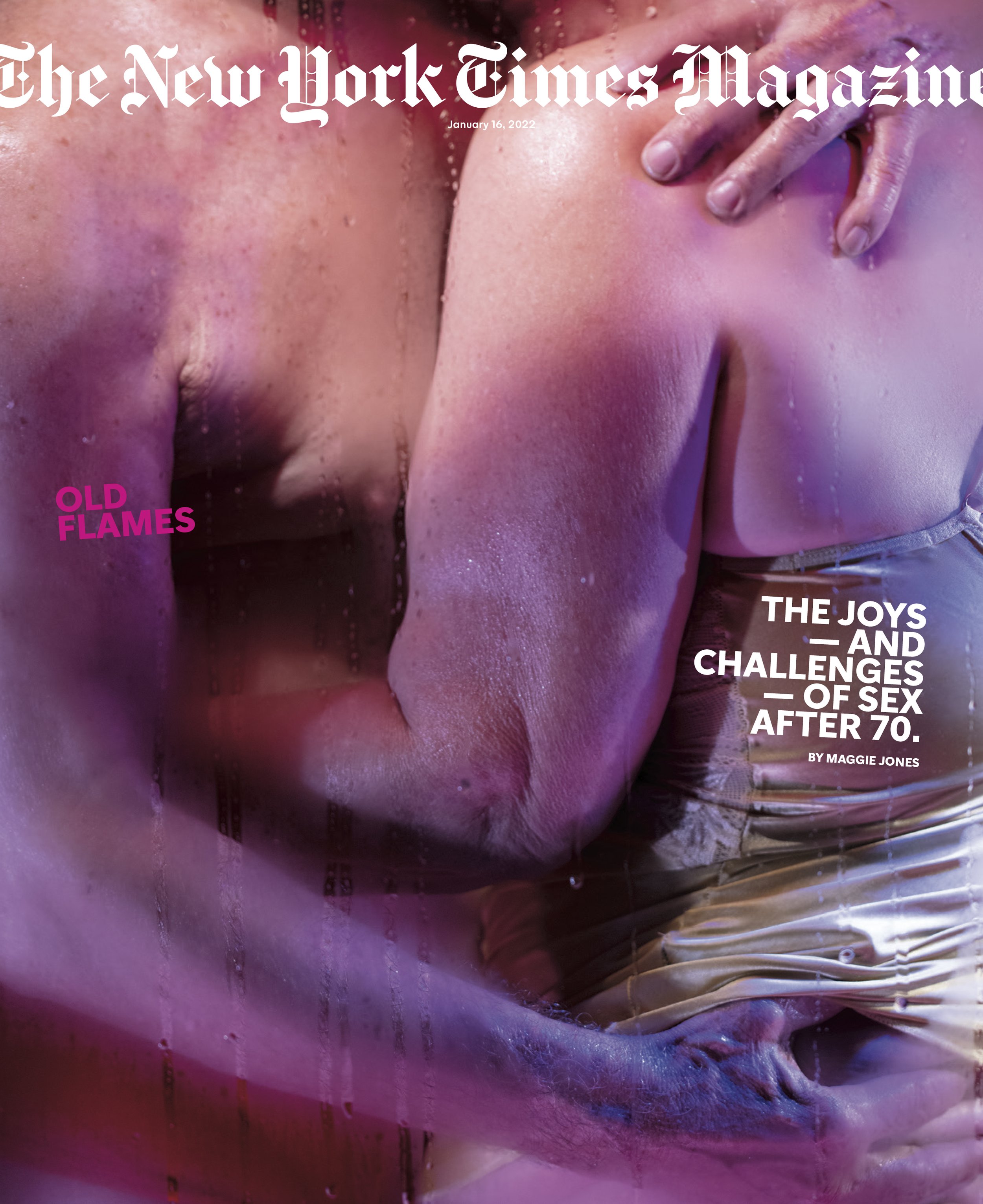

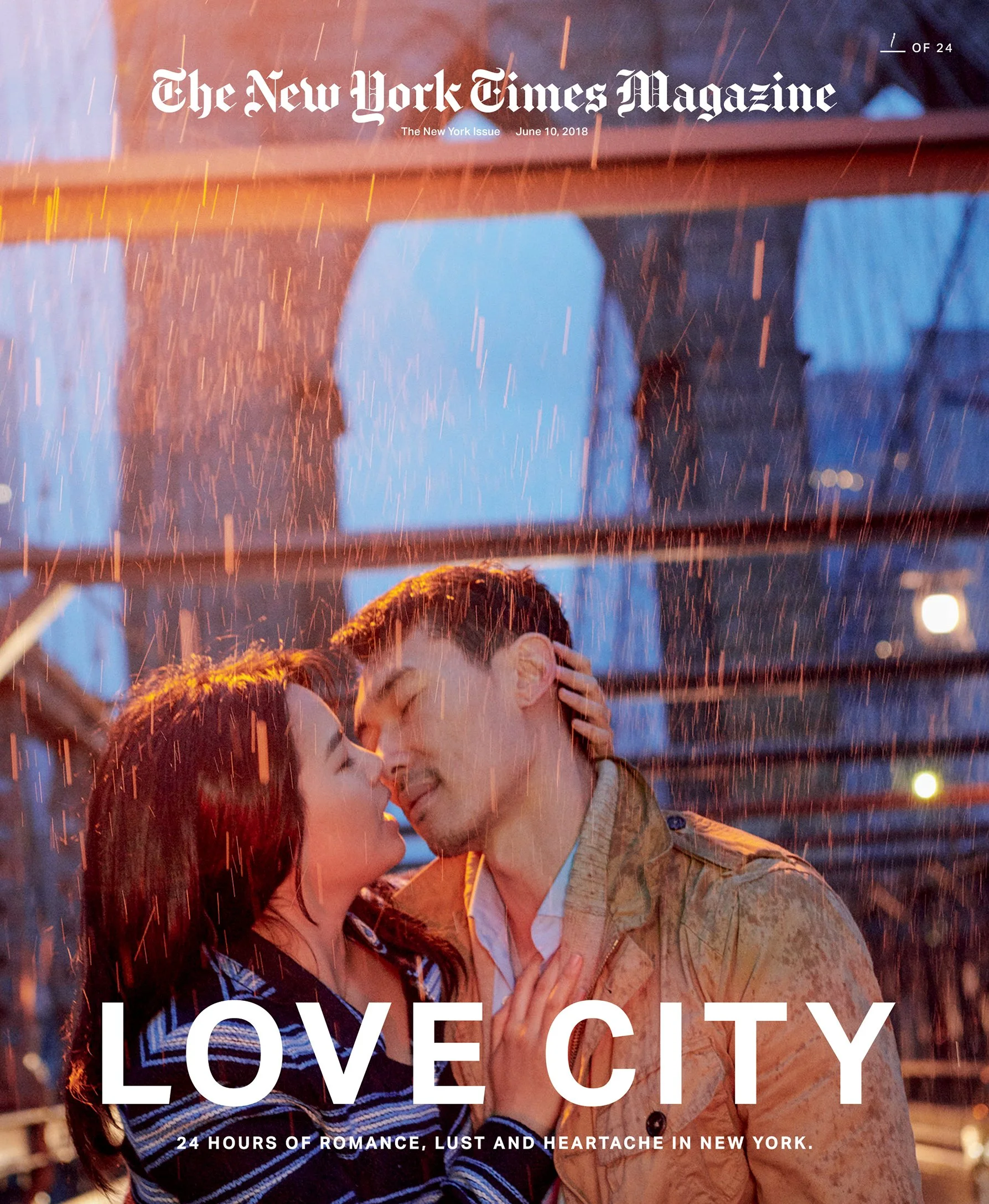

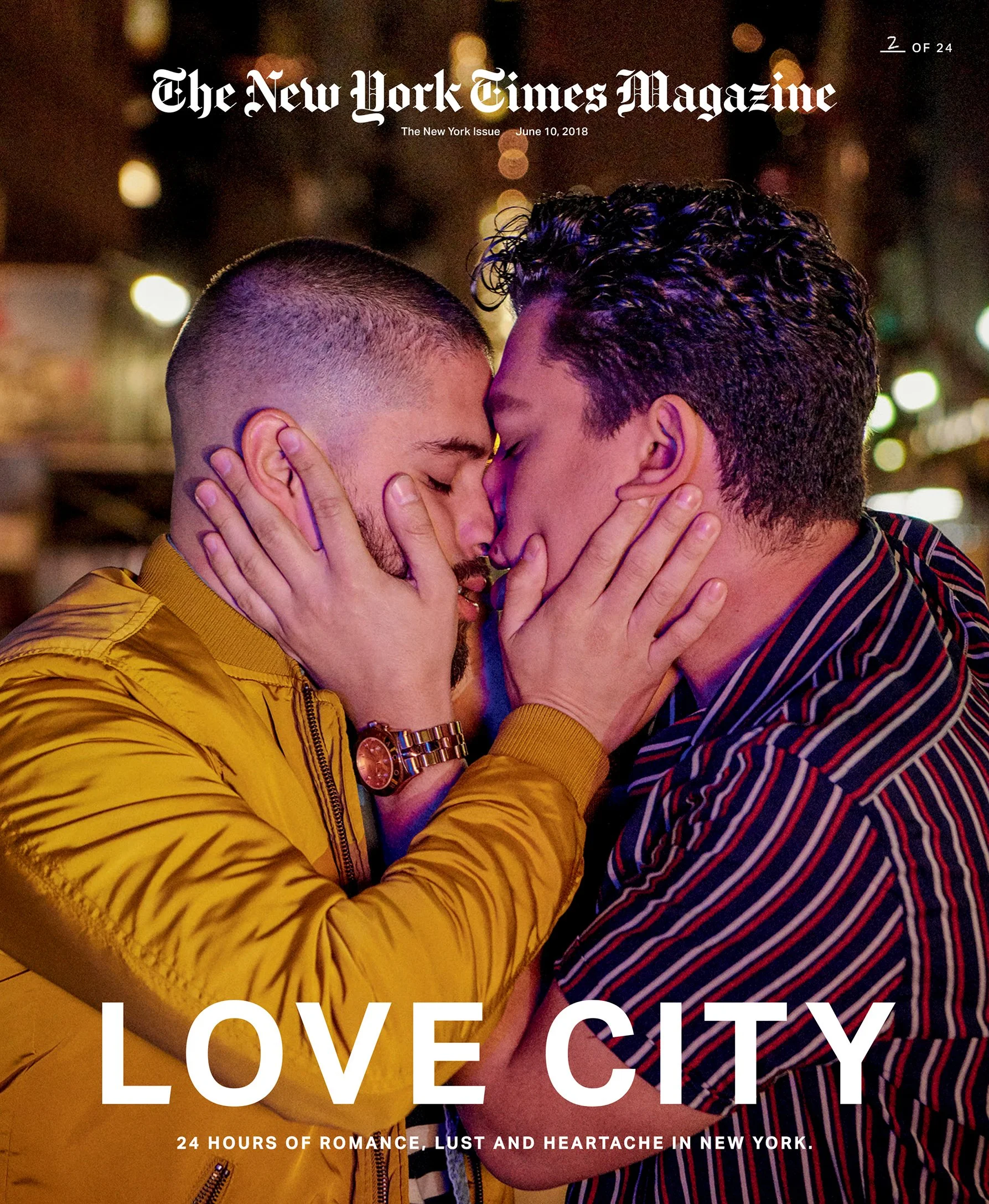

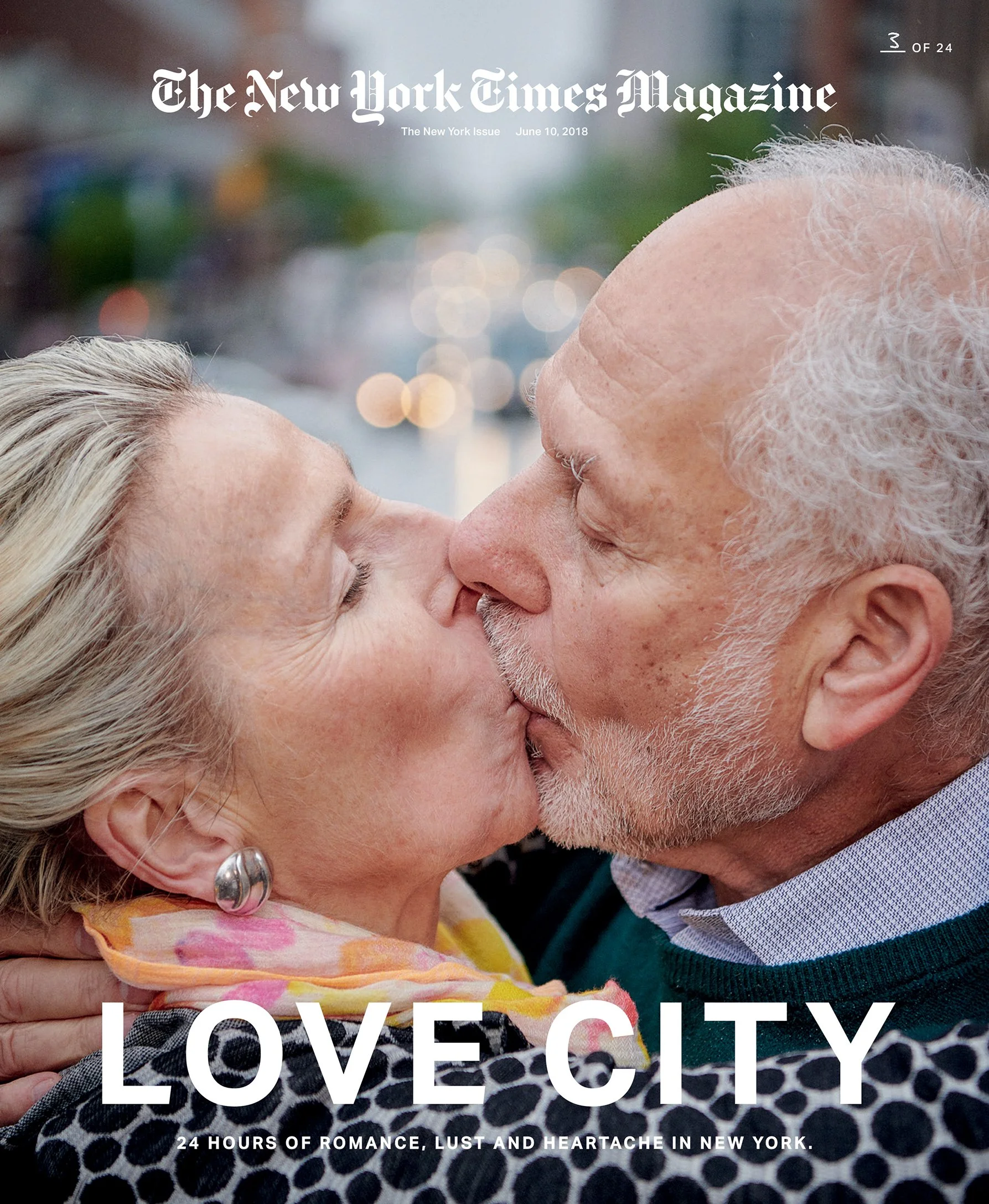

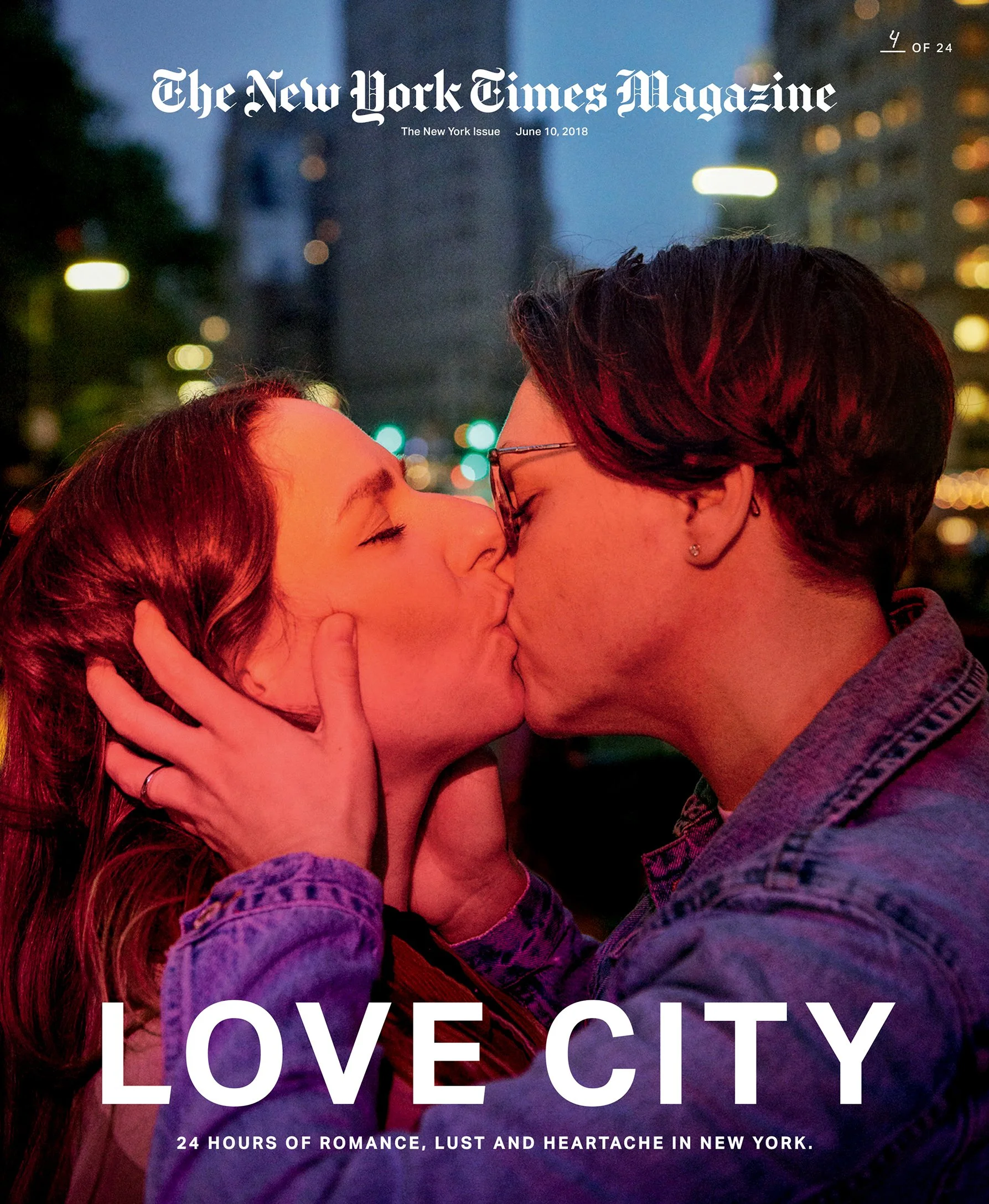

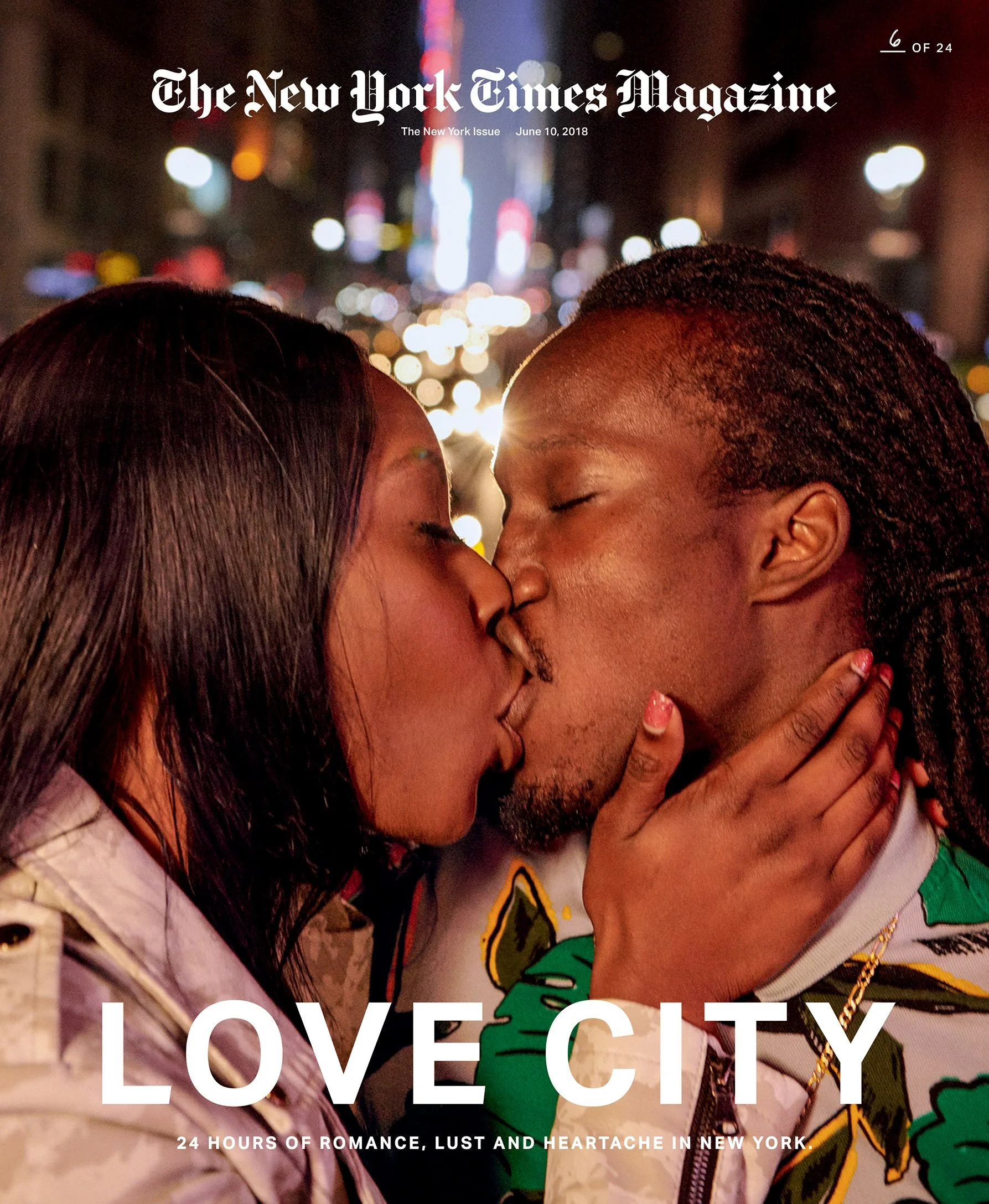

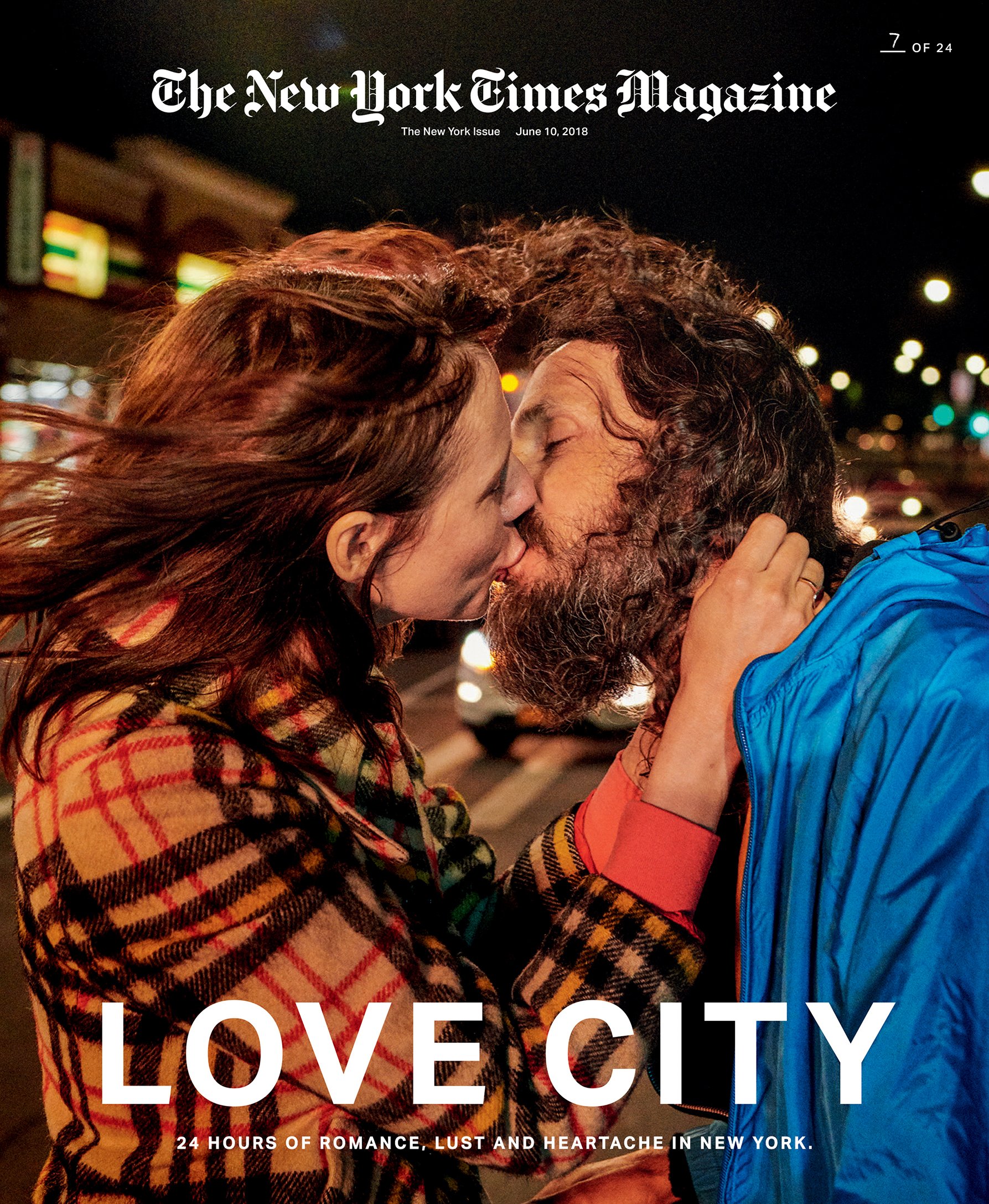

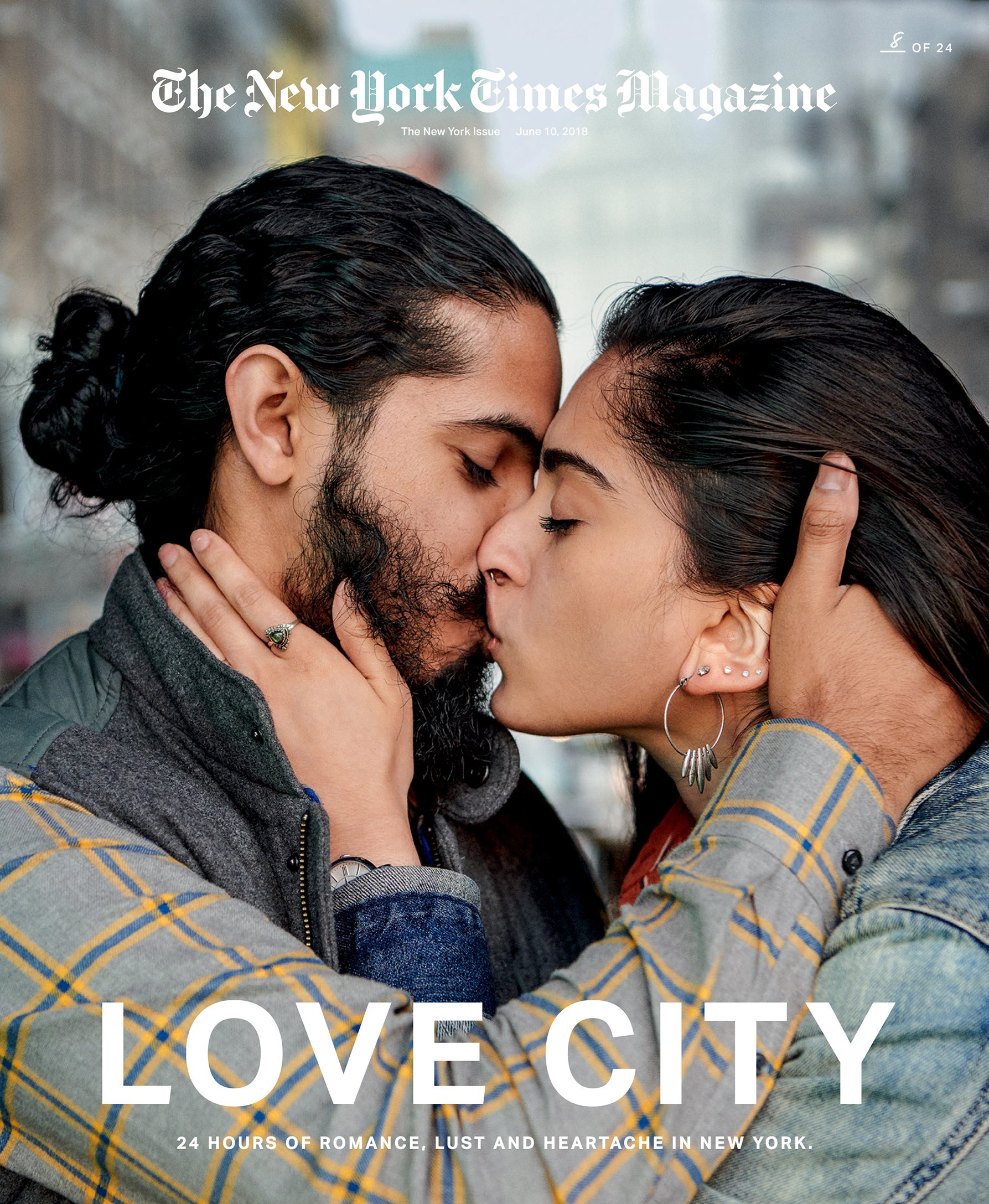

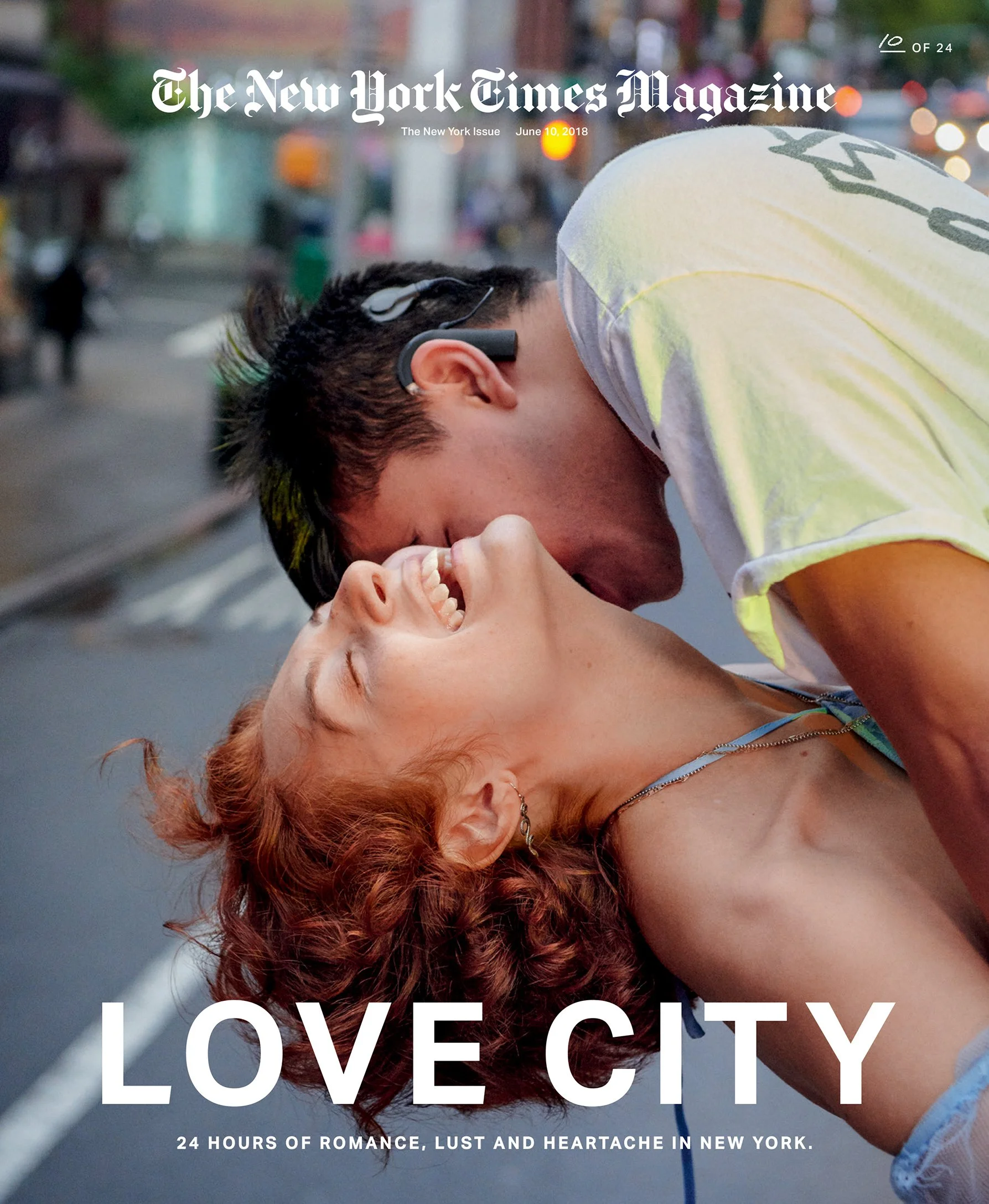

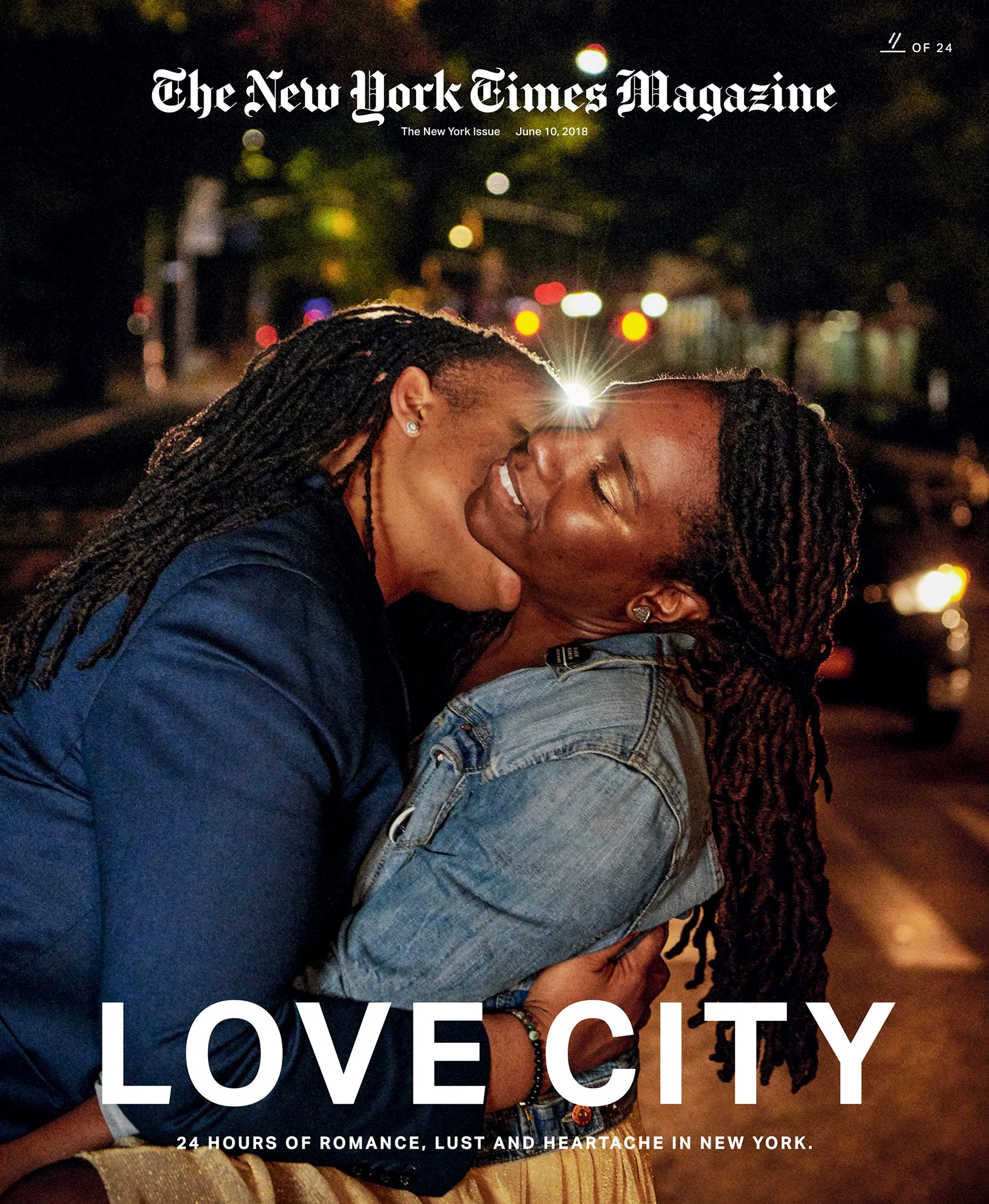

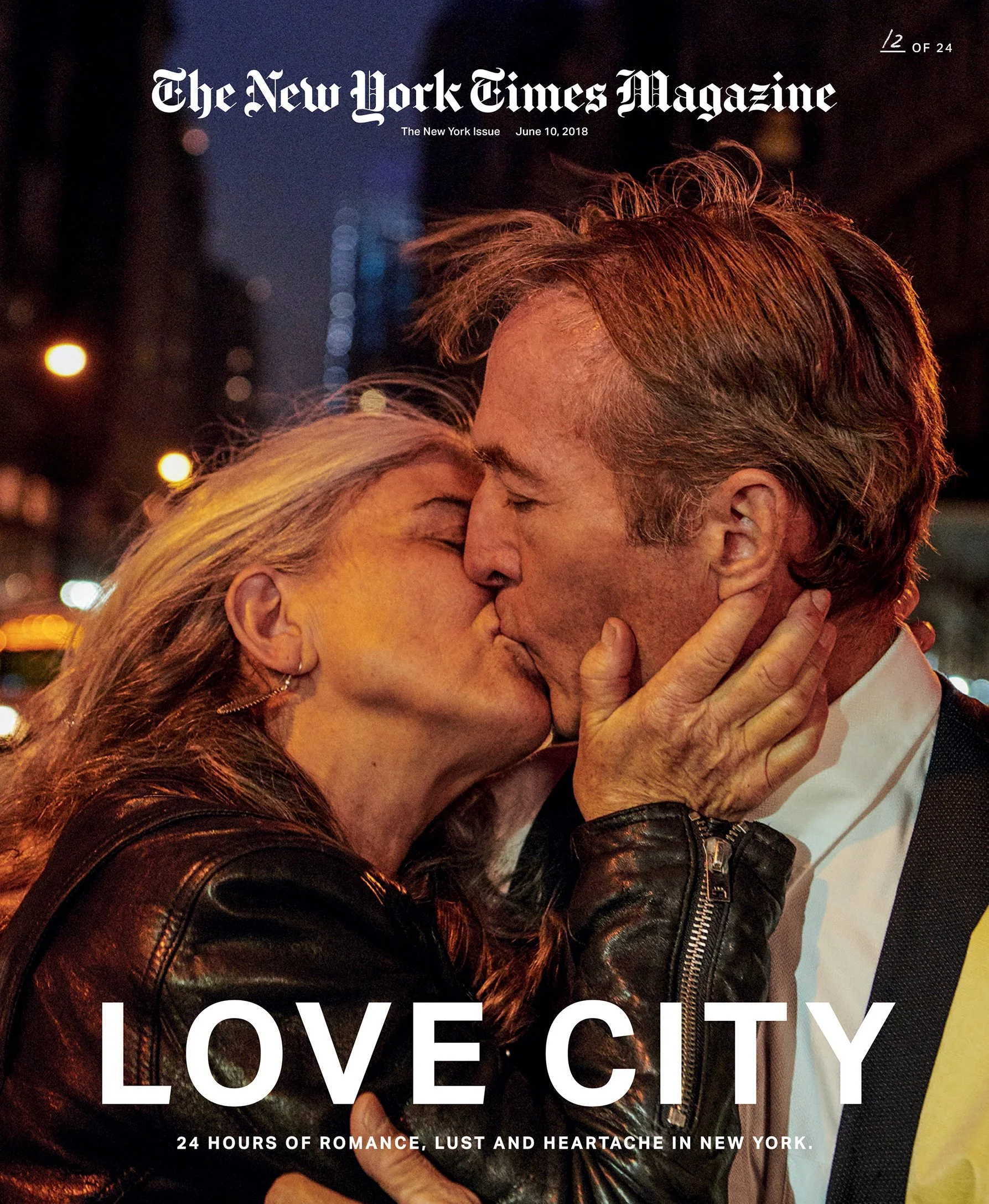

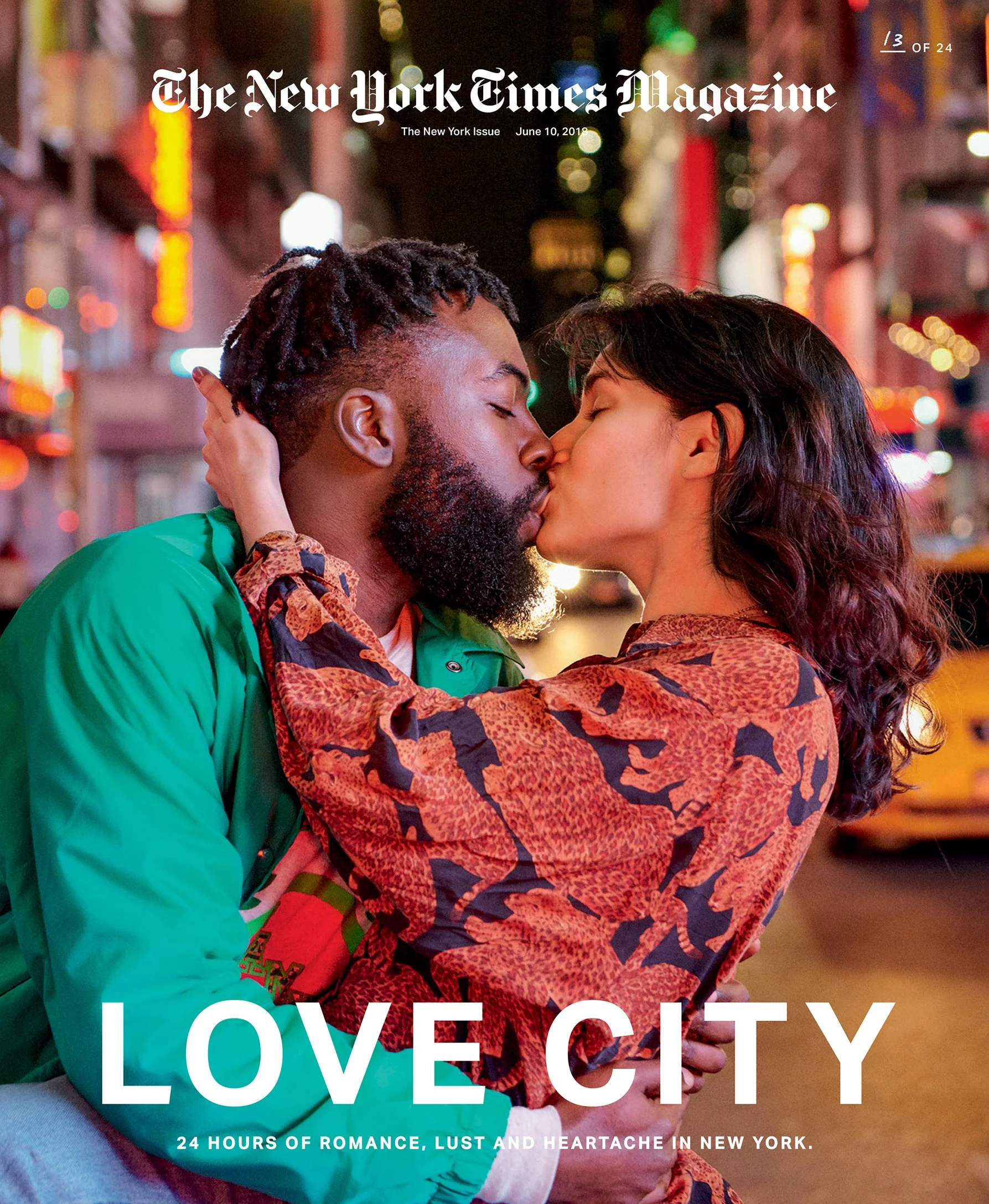

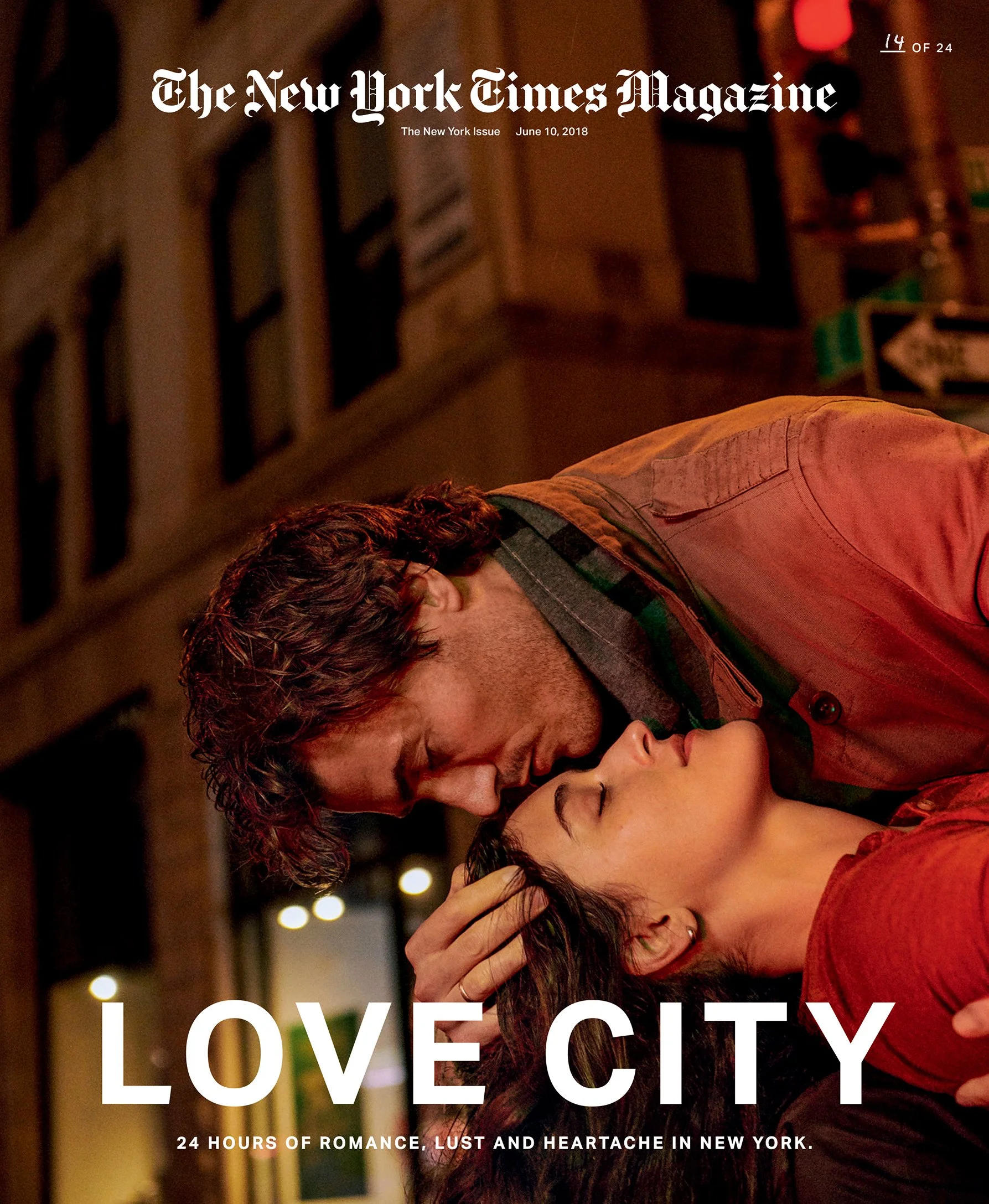

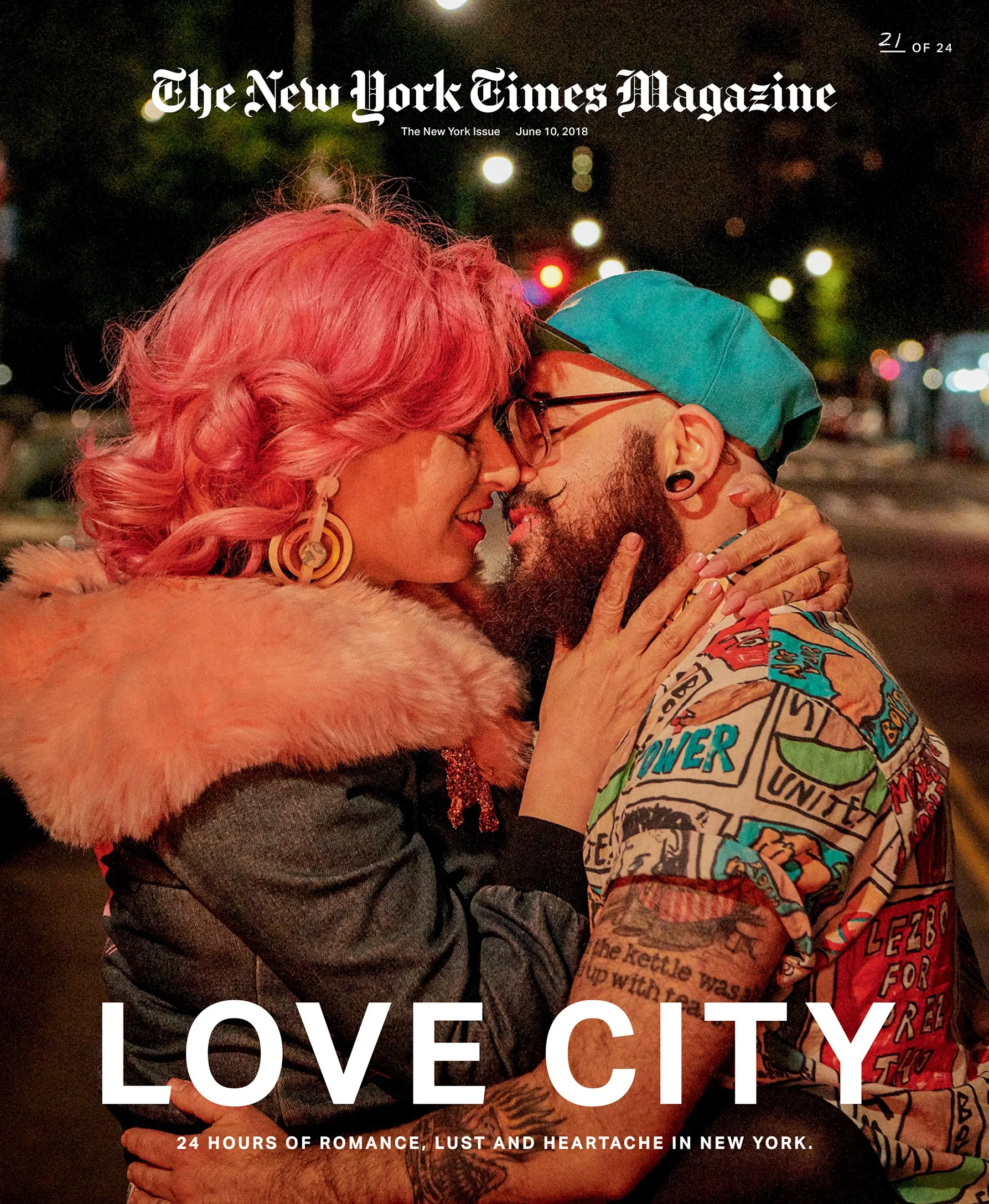

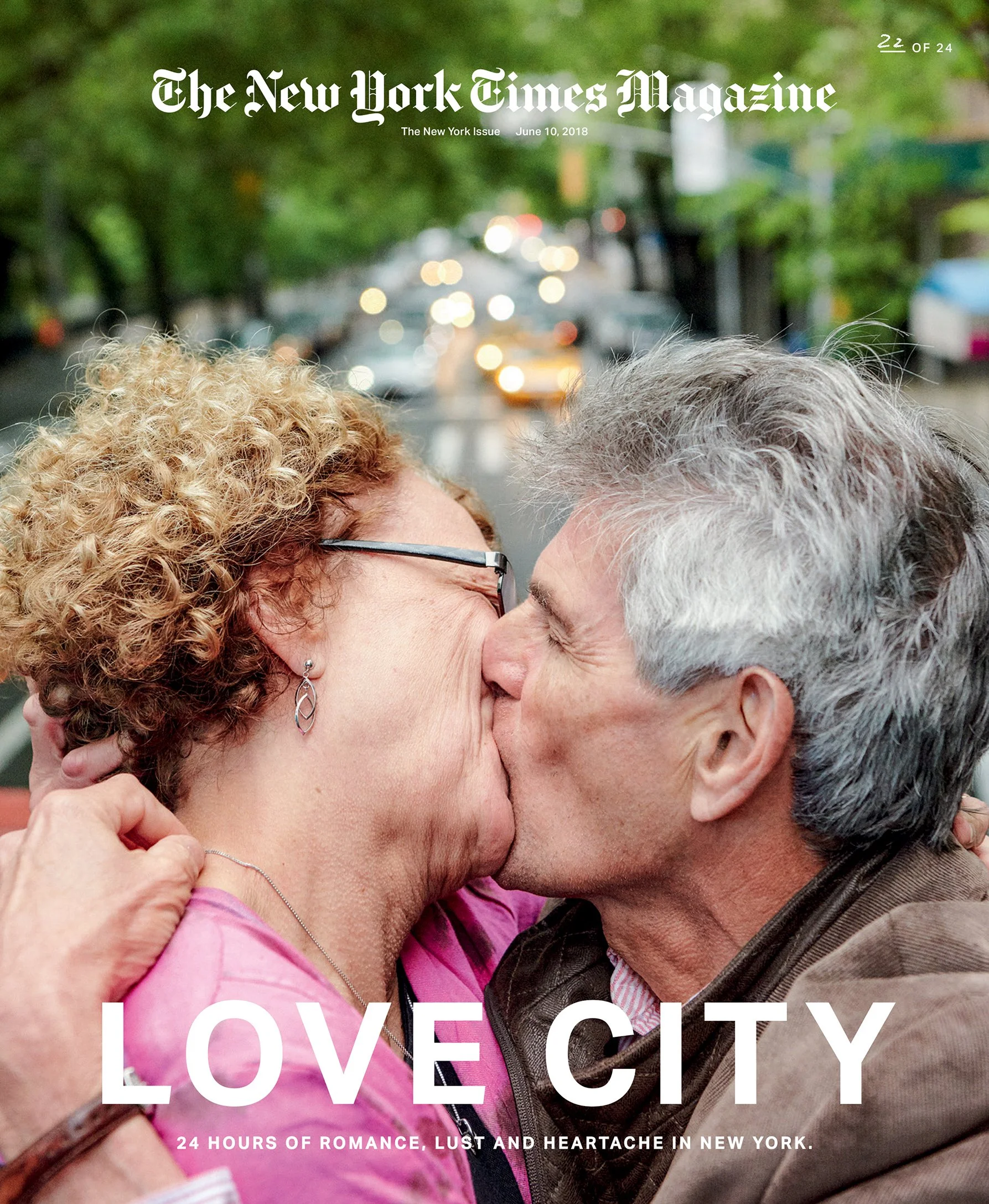

Love City: 24 Hours of Romance, Lust, and Heartache in New York Photographs by Ryan McGinley

“Love City” was a special issue of The New York Times Magazine dedicated entirely to love in New York City over the course of a single day: Saturday, May 19, 2018. All the photography was shot on that date between 12 a.m. and 11:59 p.m. By choosing this theme and so tightly limiting the time frame, the magazine hoped to convey the city’s magical density of intimacies, the way it juxtaposes the private communion of one pair of lovers with the rollicking public energy of the bustling crowd—itself composed of numberless lovers communing privately amid the noise, all the center of their own universe.