Everyone Is a Salesman

A conversation with designer Gael Towey (Martha Stewart Living, MSLO, Clarkson Potter, House & Garden, more)

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF COMMERCIAL TYPE

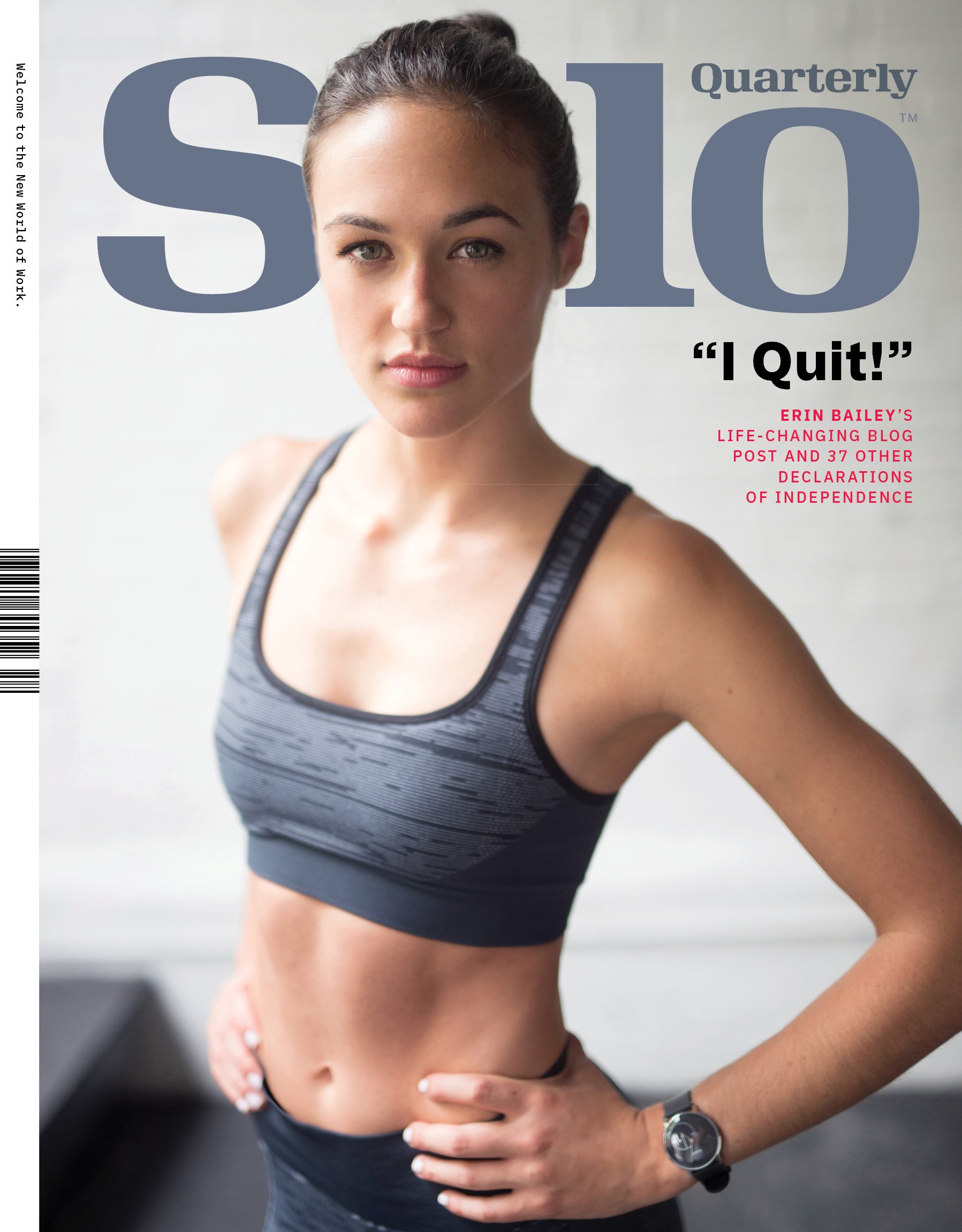

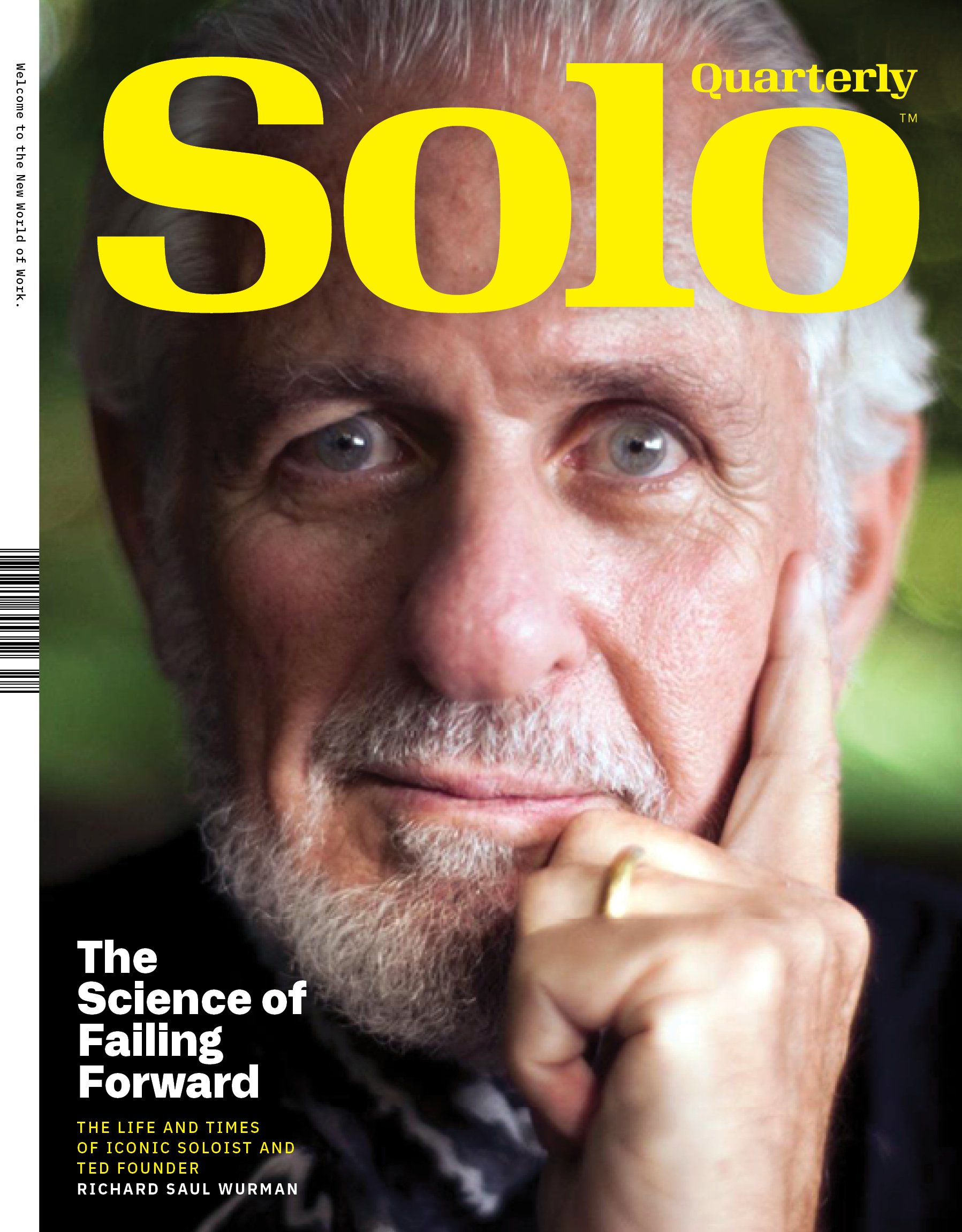

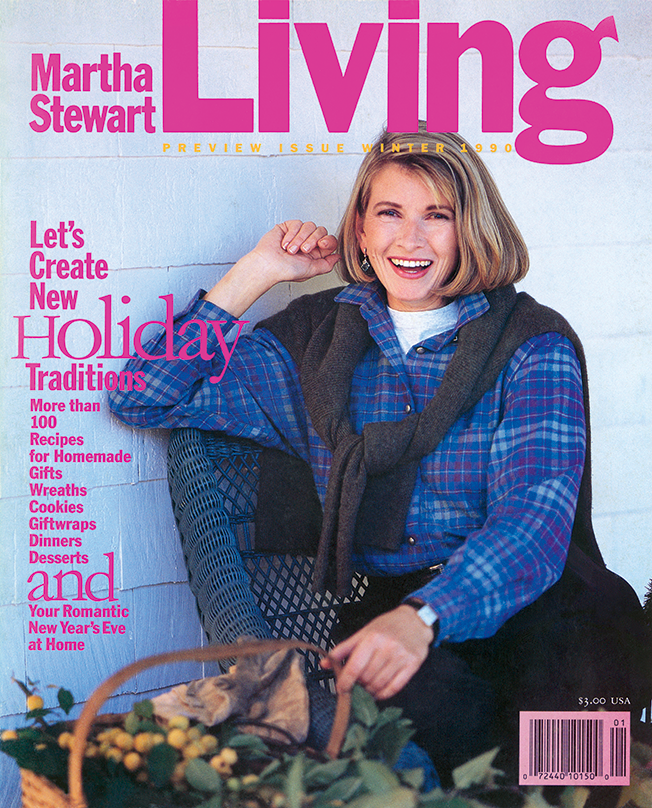

In 1995, New York magazine declared Martha Stewart the “Definitive American Woman of Our Time.” And, as the saying goes, sort of, behind every Definitive American Woman of Our Time is another Definitive American Woman of Our Time. And that’s today’s guest, designer Gael Towey.

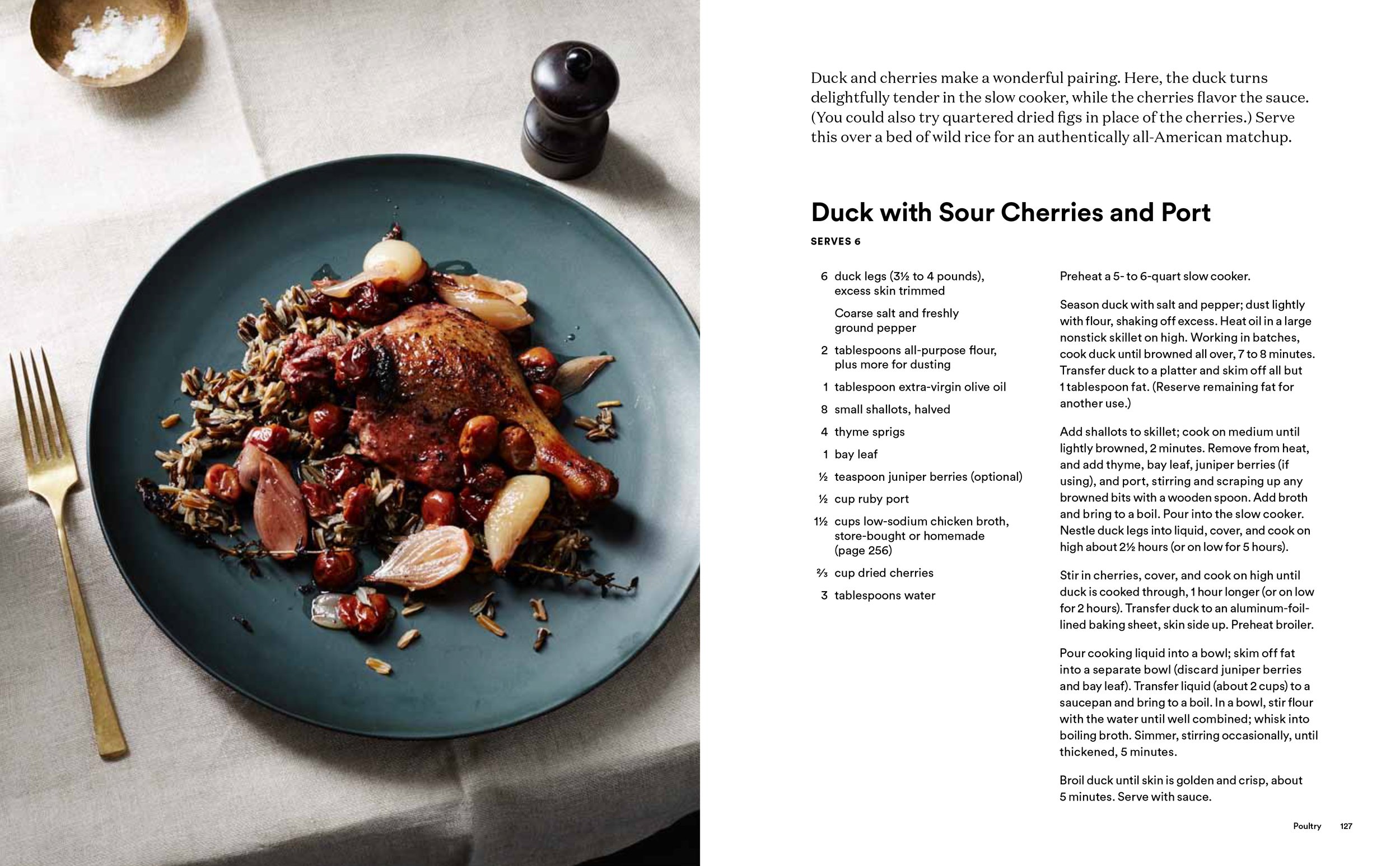

But let’s back up. It’s 1982, and Martha Stewart, then known as the “domestic goddess” — or some other equally dismissive moniker — published her first book, Entertaining. It was a blockbuster success that was soon followed by a torrent of food, decorating, and lifestyle bestsellers.

In 1990, after a few years making books with the likes of Jackie Onassis, Irving Penn, Arthur Miller, and, yes, Martha Stewart, Towey and her Clarkson Potter colleague, Isolde Motley, were lured away by Stewart, who had struck a deal with Time Inc. to conceive and launch a new magazine.

Towey’s modest assignment? Define and create the Martha Stewart brand. Put a face to the name. From scratch. And then distill it across a rapidly-expanding media and retail empire.

In the process, Stewart, Motley, and Towey redefined everything about not only women’s magazines, but the media industry itself — and spawned imitations from Oprah, Rachael, and even Rosie.

By the turn of the millennium, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, as it was rebranded in 1997, included seven magazines, multiple TV projects, a paint collection with Sherwin-Williams, a mail-order catalog, Martha by Mail, multimillion-dollar deals with retailers Kmart, Home Depot, and Macy’s, a line of crafts for Michael’s, a custom furniture brand with Bernhardt, and even more bestselling books. And the responsibility for the visual identity of all of it fell to Towey and her incredibly talented team. It was a massive job.

We talk to Towey about her early years in New Jersey, about being torn between two men (“Pierre” and Stephen), eating frog legs with Condé Nast’s notorious editorial director, Alexander Liberman, and, about how, when all is said and done, life is about making beautiful things with extraordinary people.

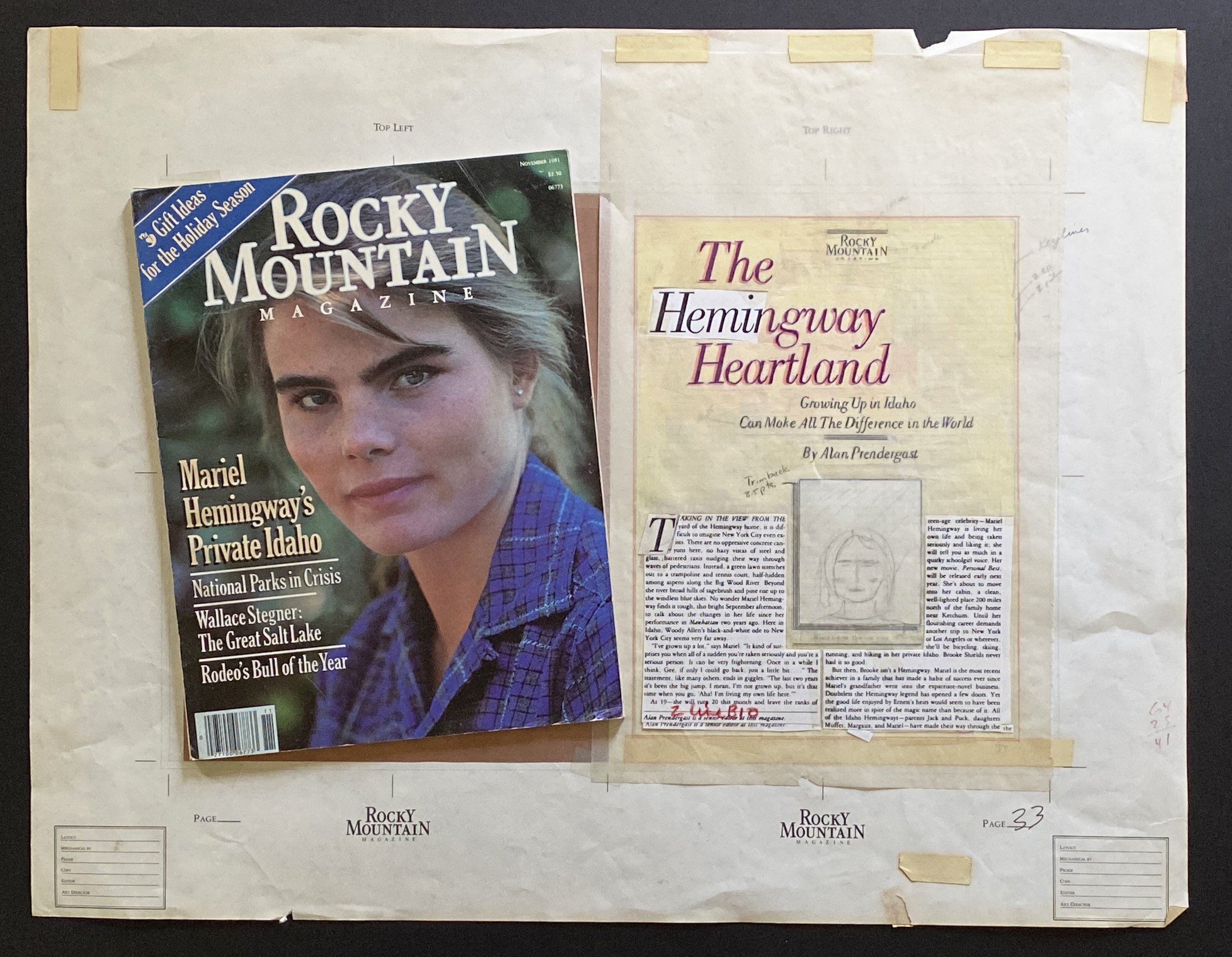

“I’m a hard worker. It never bothered me that I was essentially a mechanical artist. These are the days of getting lino proofs and using rubber cement and all of that. I was just so happy to be in the room.”

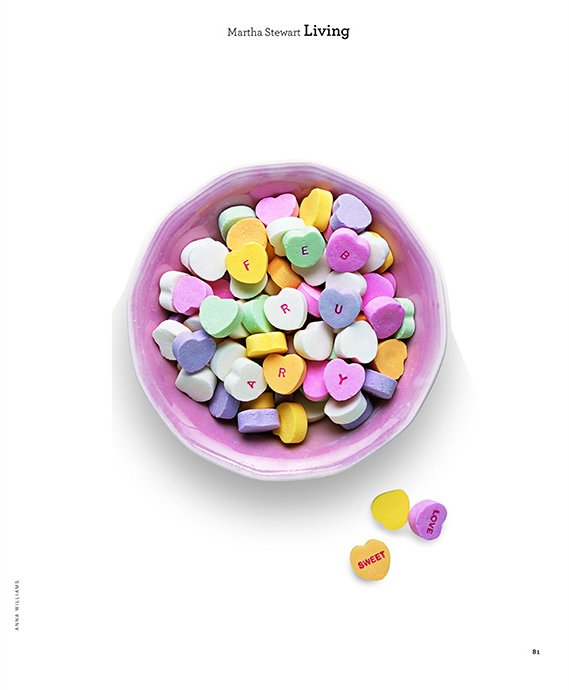

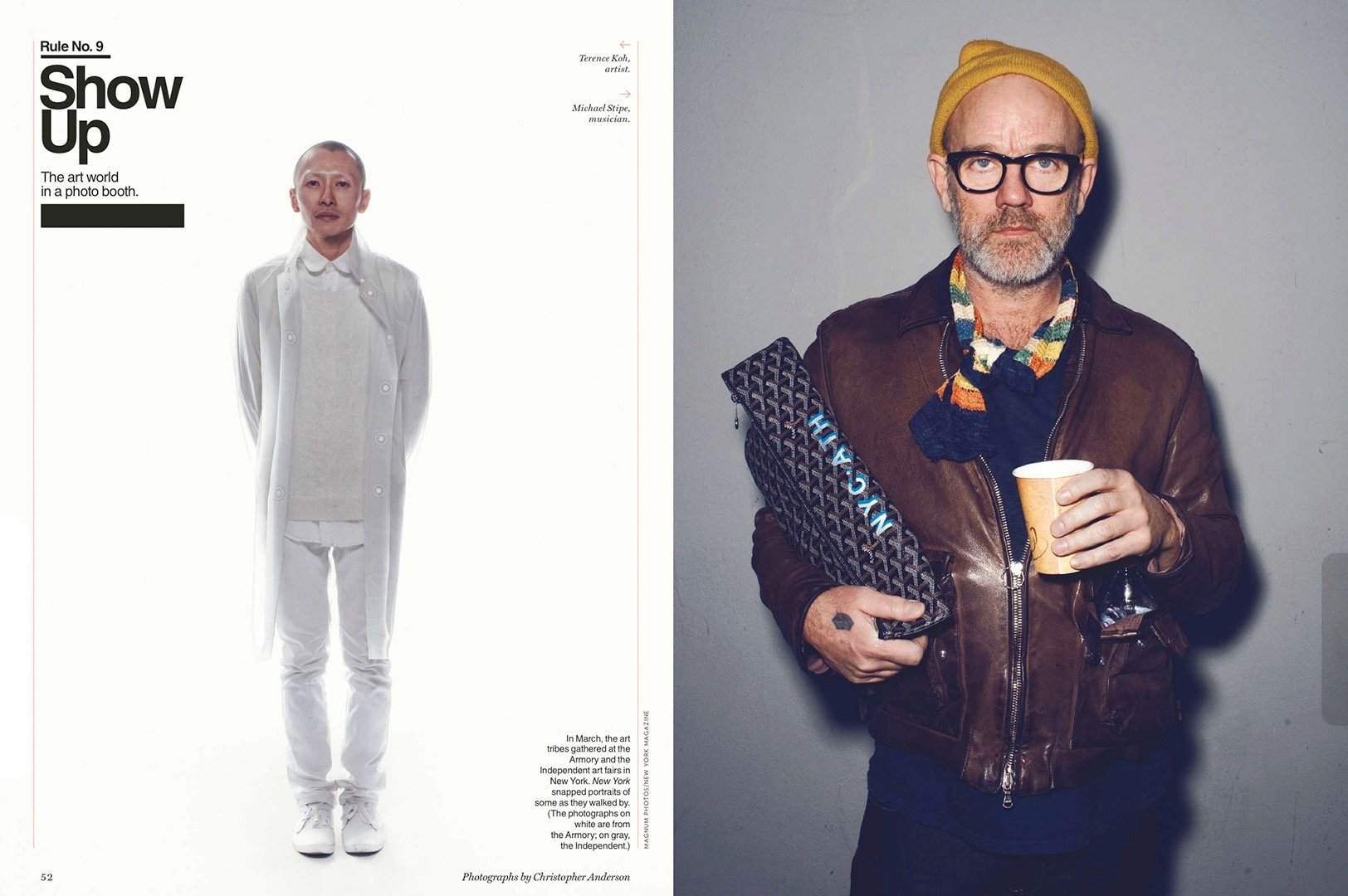

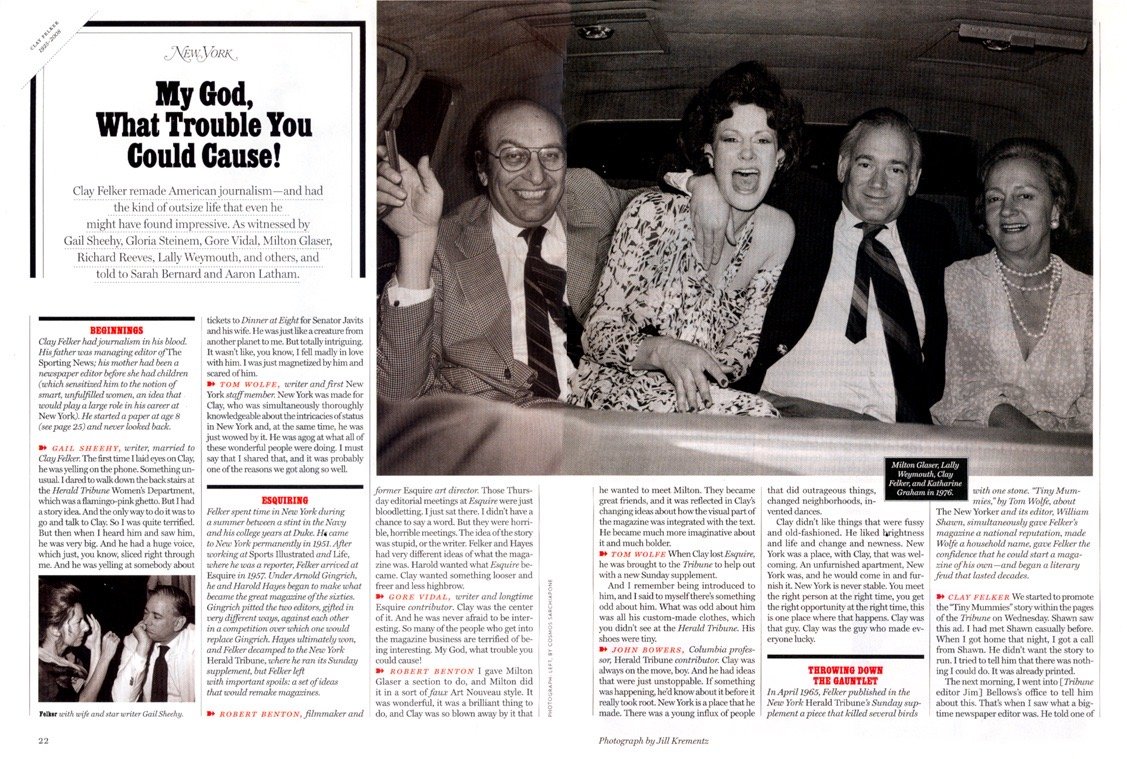

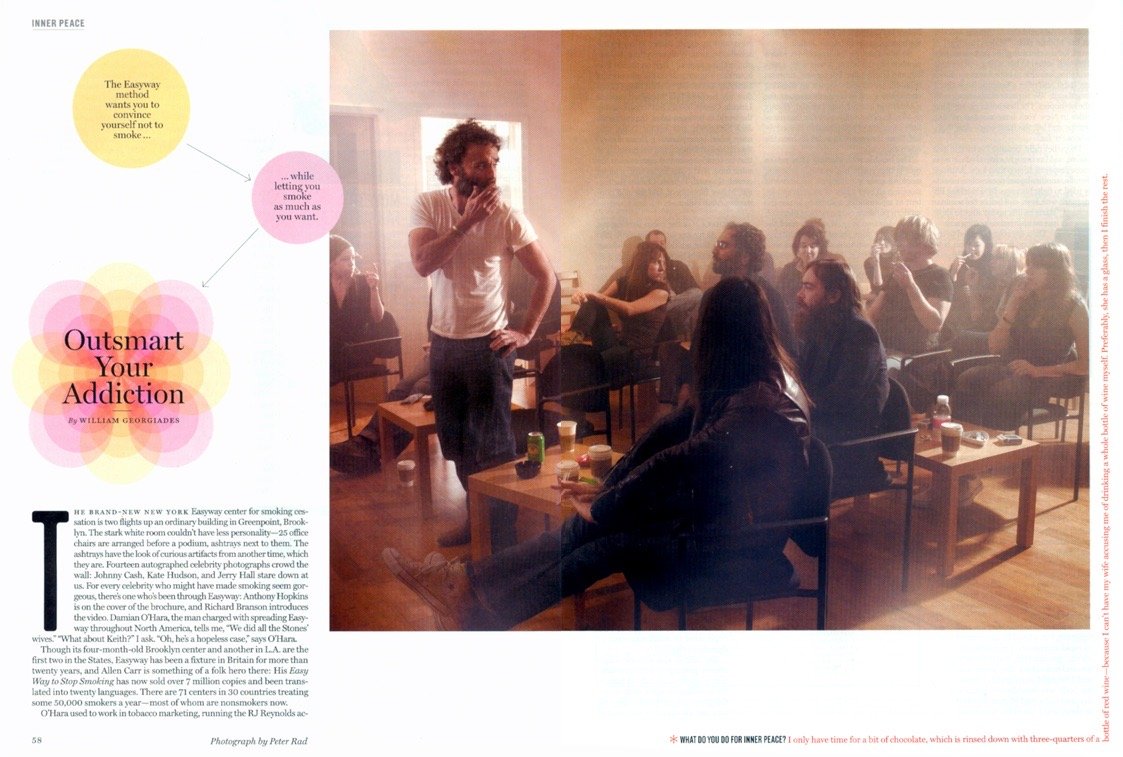

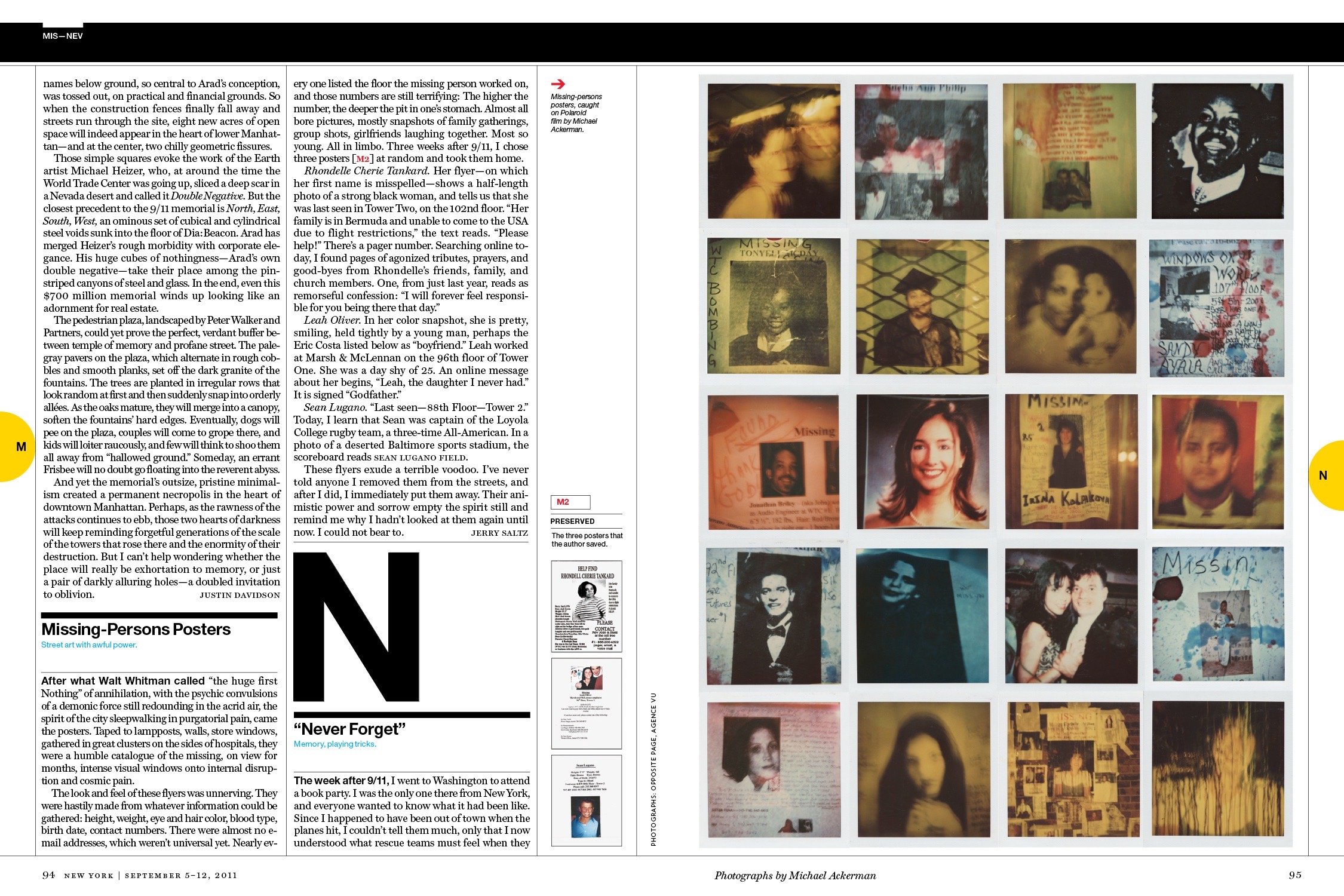

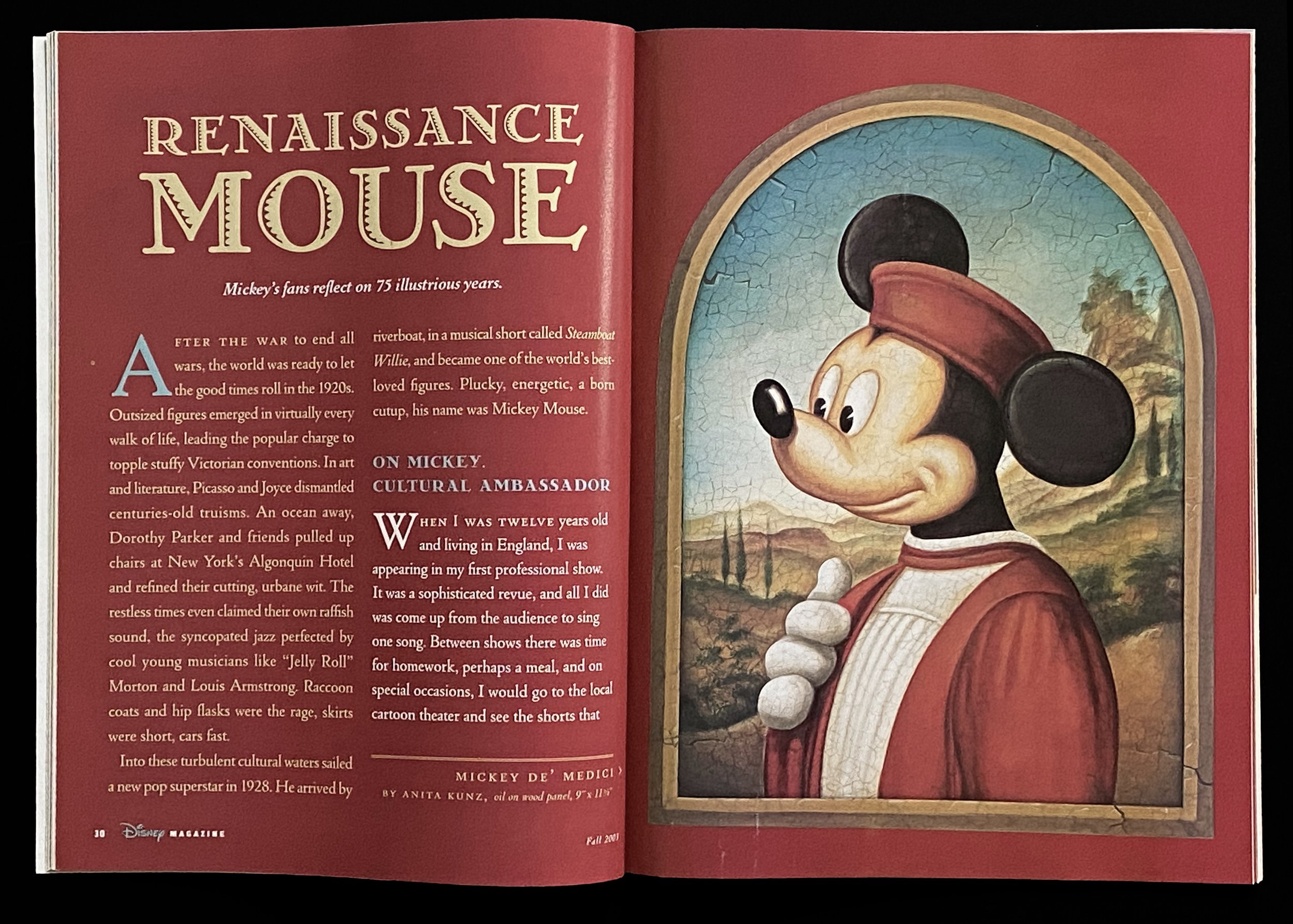

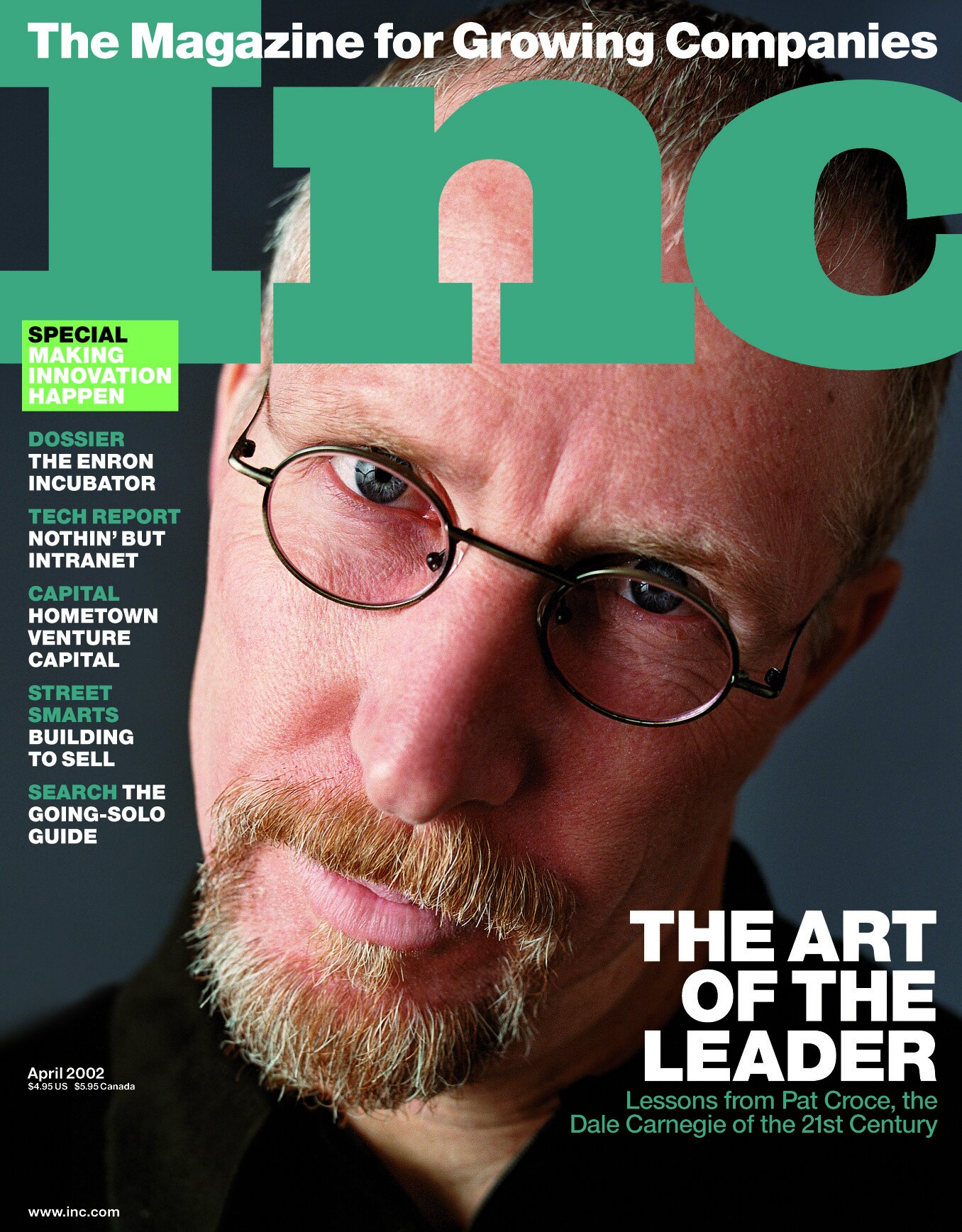

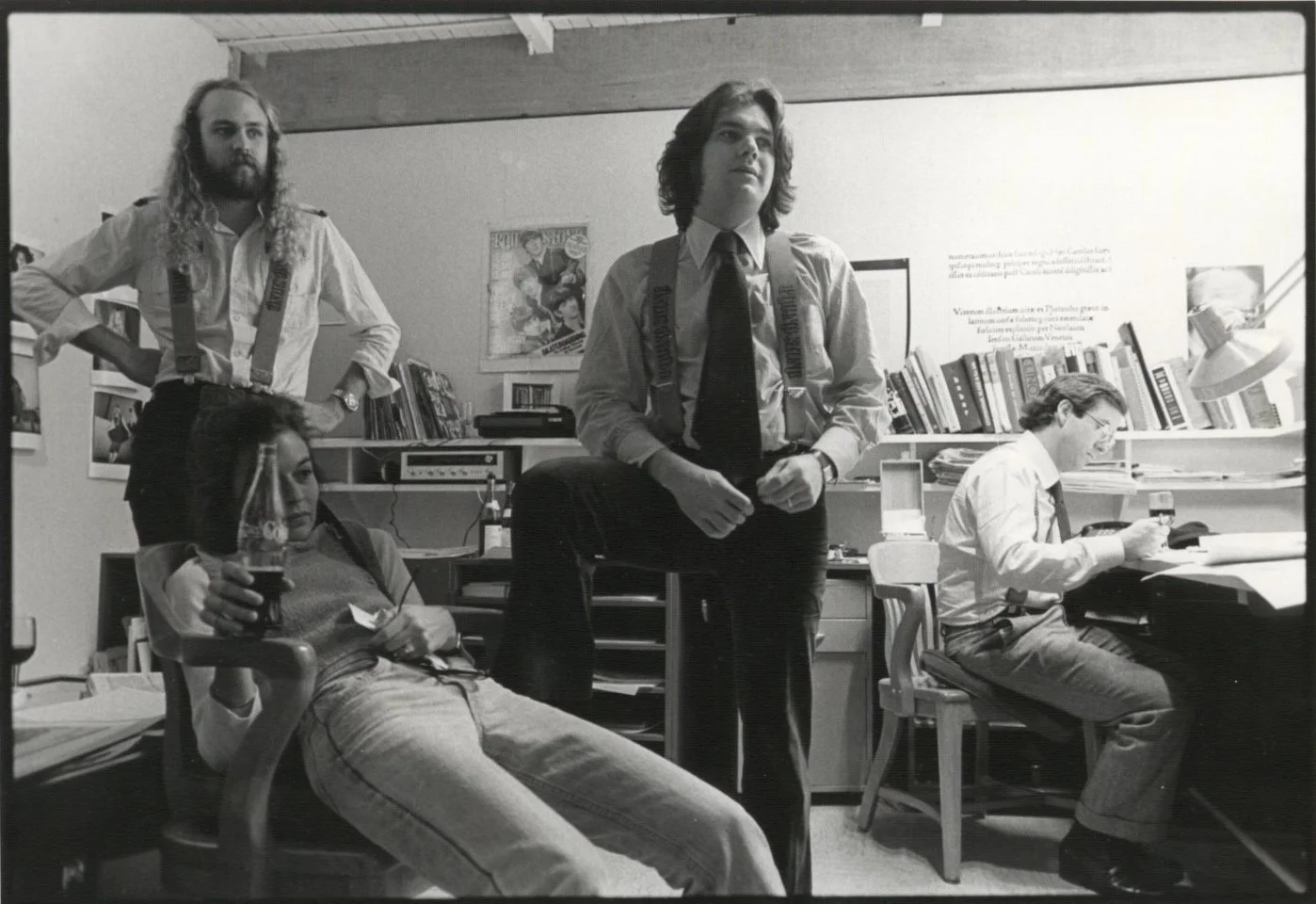

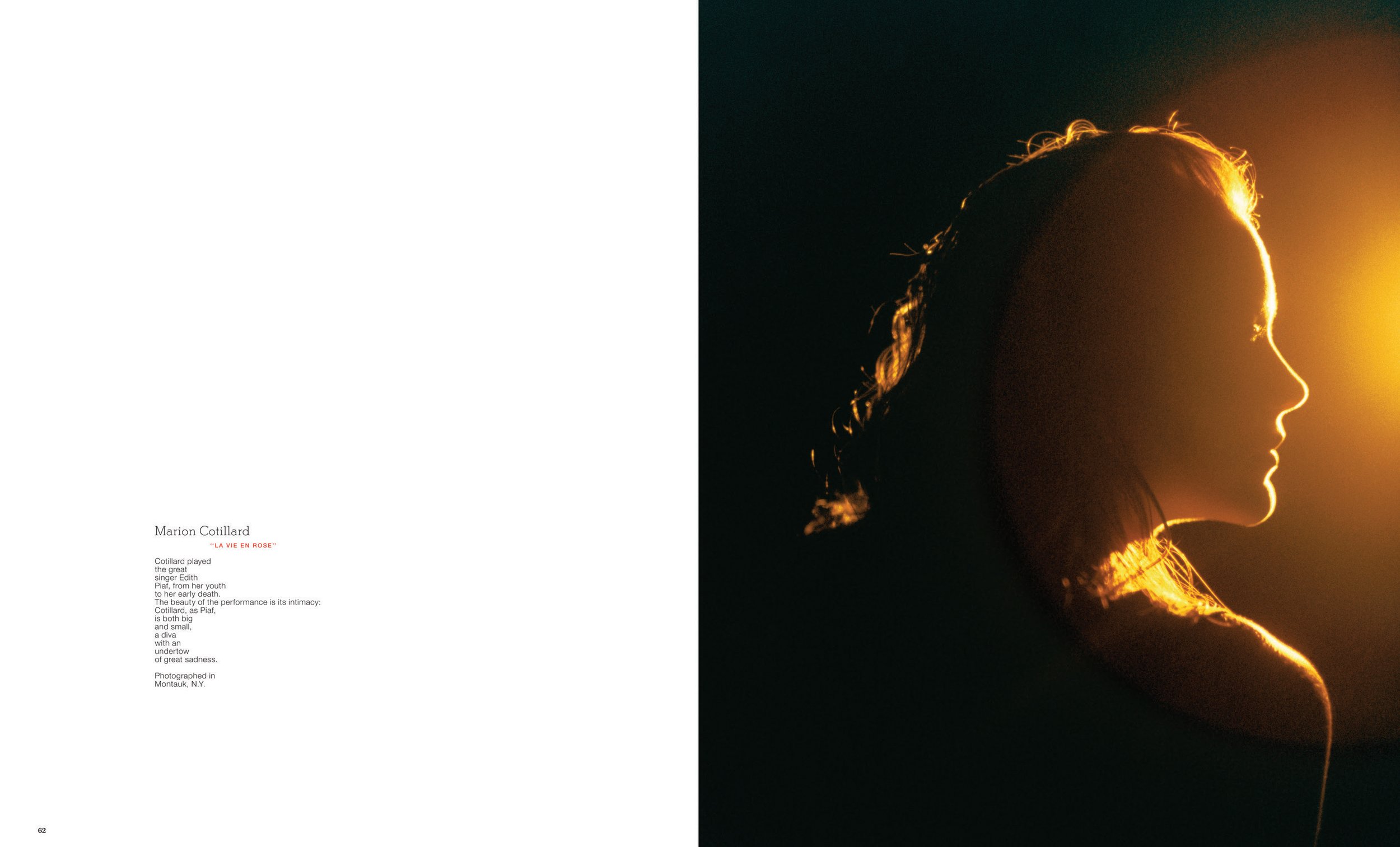

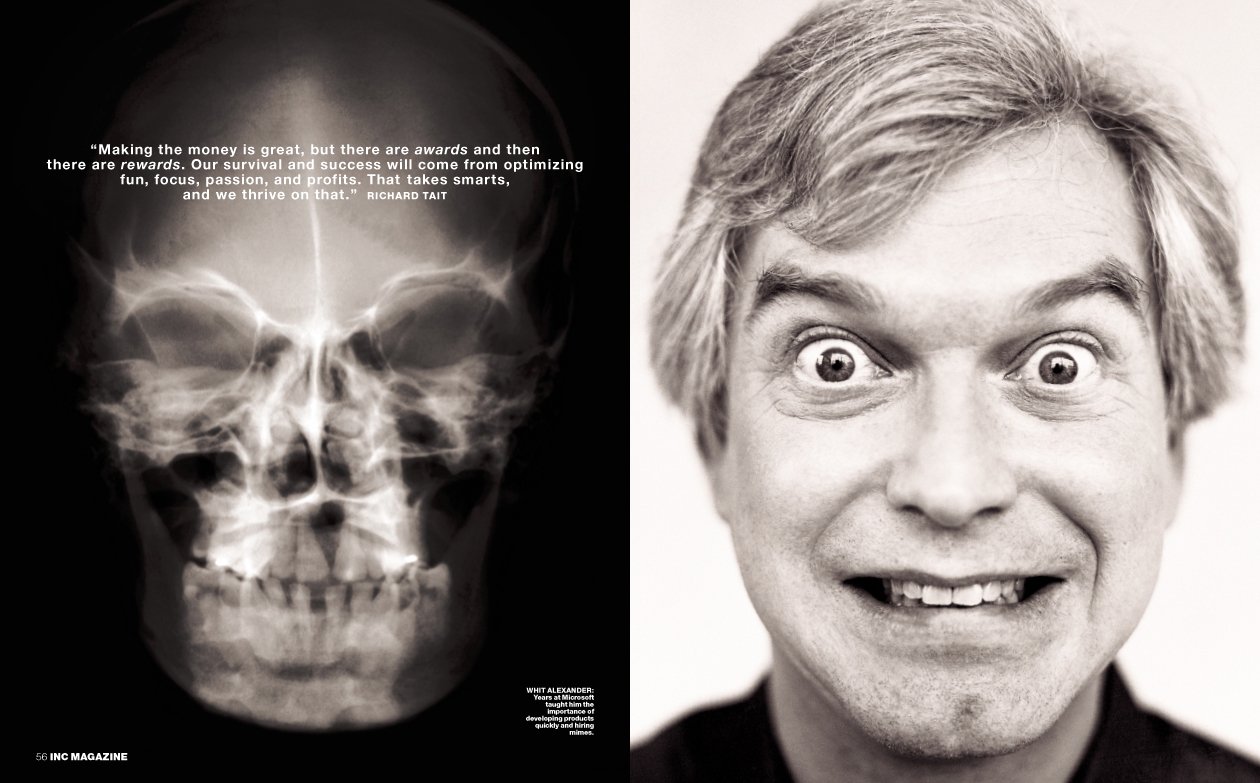

Towey (fourth from right) with the original MSL team at Time Inc.

Patrick Mitchell: Gael, your dad was in sales. Mine was too. You said he always told you, “Gael, everyone is a salesman.” How do you think that influenced your career?

Gael Towey: When I was working at Clarkson Potter publishers, I was the art director, and I had to present all of my covers to the ad sales team, and also our publisher, Bruce Harris, who I really adored and I learned a lot from. I’d have to show them to Bruce first, and then I would go before the sales team panel, which was probably about 25 people.

It was a very intimidating group. And I remember going up in the elevator to this meeting, and in my mind I heard my father say, “Gael, everybody is a salesman.” And what he meant was that we are all out there, no matter who we are, basically, we are trying to convince people to agree with us. And that’s something that’s part of everything that I have done, in terms of my career.

Patrick Mitchell: You described your mother as a “crazy perfectionist.” Can you tell us a little bit about her?

Gael Towey: When I was in second grade, the nuns told my mother that I had to stay back because I was a really poor reader. I could not spell. I would get so mixed up between like “girl” and “grill” and, you know, all of these things.

And in those days people didn’t know about dyslexia. So my mother hired a tutor. And the tutor told my mother that I was not dyslexic. I was just slow. So I had this kind of growing up where I was constantly fighting against people thinking that I was stupid. And my mother, by the time I got to college, and I kept failing, it was very depressing, but it made me very strong.

Anyway, I went to college, and when I was writing letters home, my mother would attach a typed list of all of the words that I misspelled to the top of my letter and return it to me.

Patrick Mitchell: What was that relationship like?

Gael Towey: Difficult.

Patrick Mitchell: Is she still with us?

Gael Towey: No, she is not. She’s not still with us. You know what? It gave me strength to go head to head with Martha when I needed to.

Debra Bishop: Gael, where does your creativity come from? Was there crafting or cooking in your early days?

Gael Towey: You know, I’ve been listening to a lot of your podcasts and all of them have made me think back about moments in my career, or my life, or my training, that I hadn’t really thought about. And I went to Boston University. I had a terrible graphic design training, but what I did take is painting, and sculpture, and photography, and art history, and history of photography, and printmaking, and pottery, and all of those things prepared me to be a good art director because they were all about imagining something that you would make. And as you know, Deb, because you and I worked together at Martha Stewart Living, it was all about making stuff up.

Debra Bishop: But as I recall, you love to sew and you’re good at that. So maybe your mother had a hand in your early days.

You grew up in New Jersey, one of six kids. Did any of your siblings pursue creative careers as well?

Gael Towey: I did grow up in New Jersey. And I’m the oldest of six. I’m part of an enormous Catholic family. I have 45 cousins on my mother’s side. My mother was one of nine children.

And I did learn to sew as a child because we didn’t have very much money. And it was all about hand-me-downs. I got hand-me-downs from my older cousins. So if you wanted to look fashionable, you had to make your own clothes, which is what I did. Which was kind of a perfect thing because in the ’60s, of course you had, I was doing like tie dyeing sheets and making them into dresses and stuff like that. It was great training.

Debra Bishop: Oh yeah! Banana collars... remember those? And gosh, big buttons. So when you were little, did you have heroes? Did you have crushes or were inspired by certain people?

Gael Towey: I was inspired by my grandfather and I wish that I knew that beforehand. My grandfather was an OB GYN at the Margaret Hague Hospital in Jersey City, and he was a wonderful, wonderful photographer.

He had a two and a quarter Rolleiflex, which is the kind that you stare down into the ground glass, and it’s turning it around. And my grandparents’ house at the Jersey Shore was filled with his photographs of his children, and my grandfather was quite short, and you’re holding the camera kind of low, so, all the pictures of my aunts and uncles of which as I said, there are many, you’re looking up. And they were so heroic and he printed them in black and white. He was very fastidious, putting all the crop marks, et cetera, and growing up with seeing those photographs, you know, I didn’t realize this till later in my career, but it was pivotal for me, absolutely pivotal.

And the other story about my grandfather, Pop Connell, is that he delivered Martha! And she remembers they lived in Jersey City on Carlton Avenue and his office was on the bottom floor, the sort of basement floor of it. It was like a semi-attached house where you would share the driveways with your next door neighbor.

And she remembers going there on Saturdays because they only had one car in their family. And she also came from a very large family, and she remembers sitting there with her mother and her father waiting to see Dr. John Connell.

Patrick Mitchell: Wow. How did you decide to go to BU?

Gael Towey: You know, my parents didn’t take us to see any schools or anything like that, and it was all about getting financial aid because there were so many kids in our family. So you really went to the place that was going to give you financial aid.

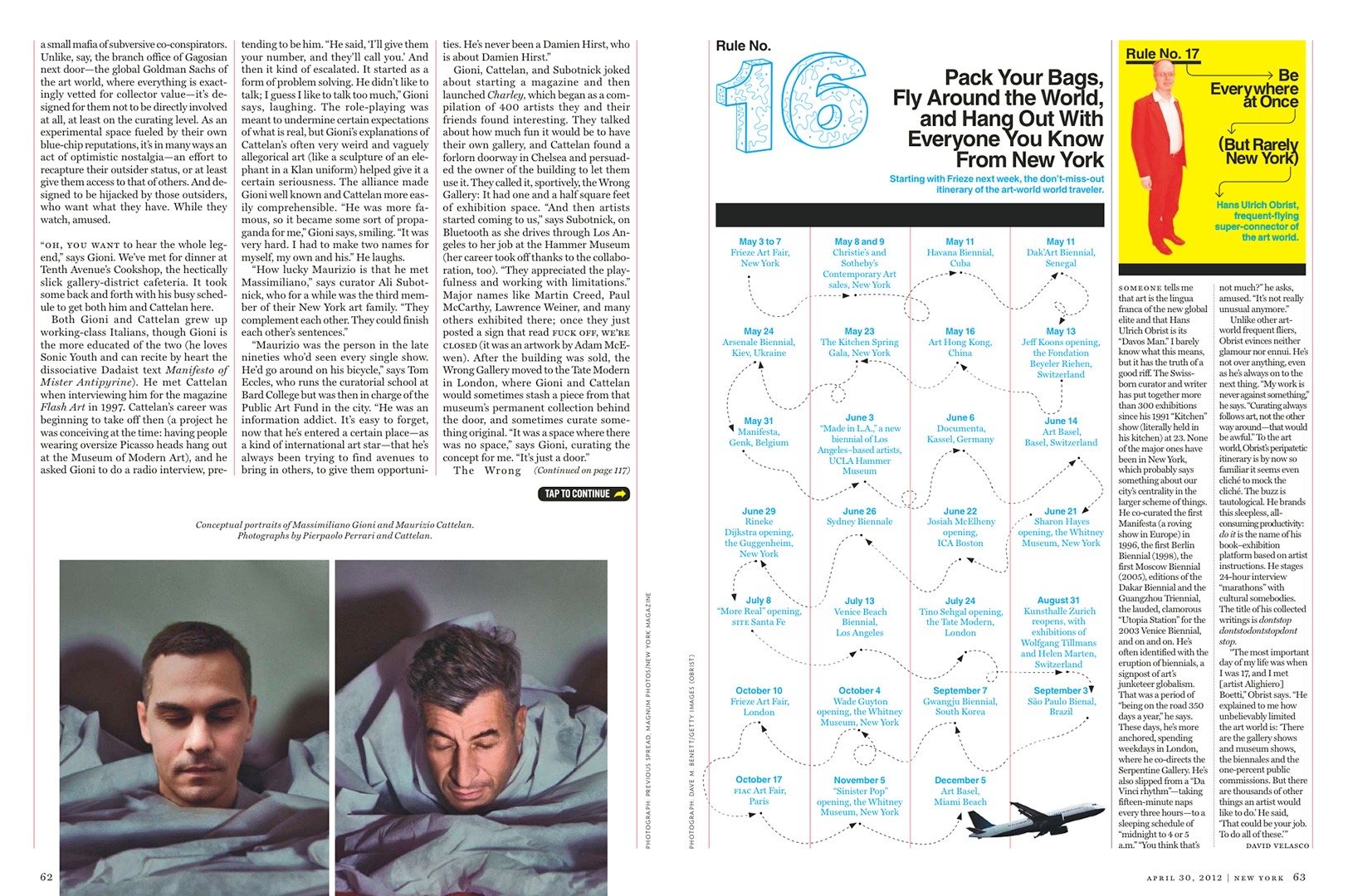

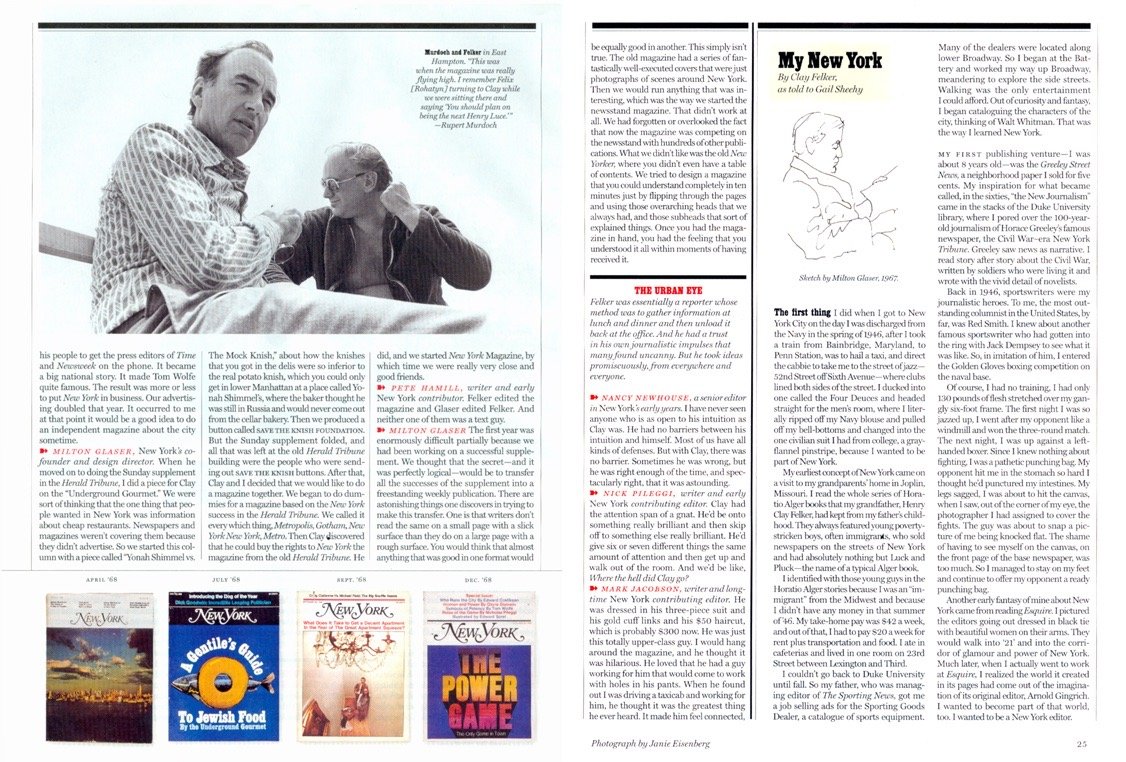

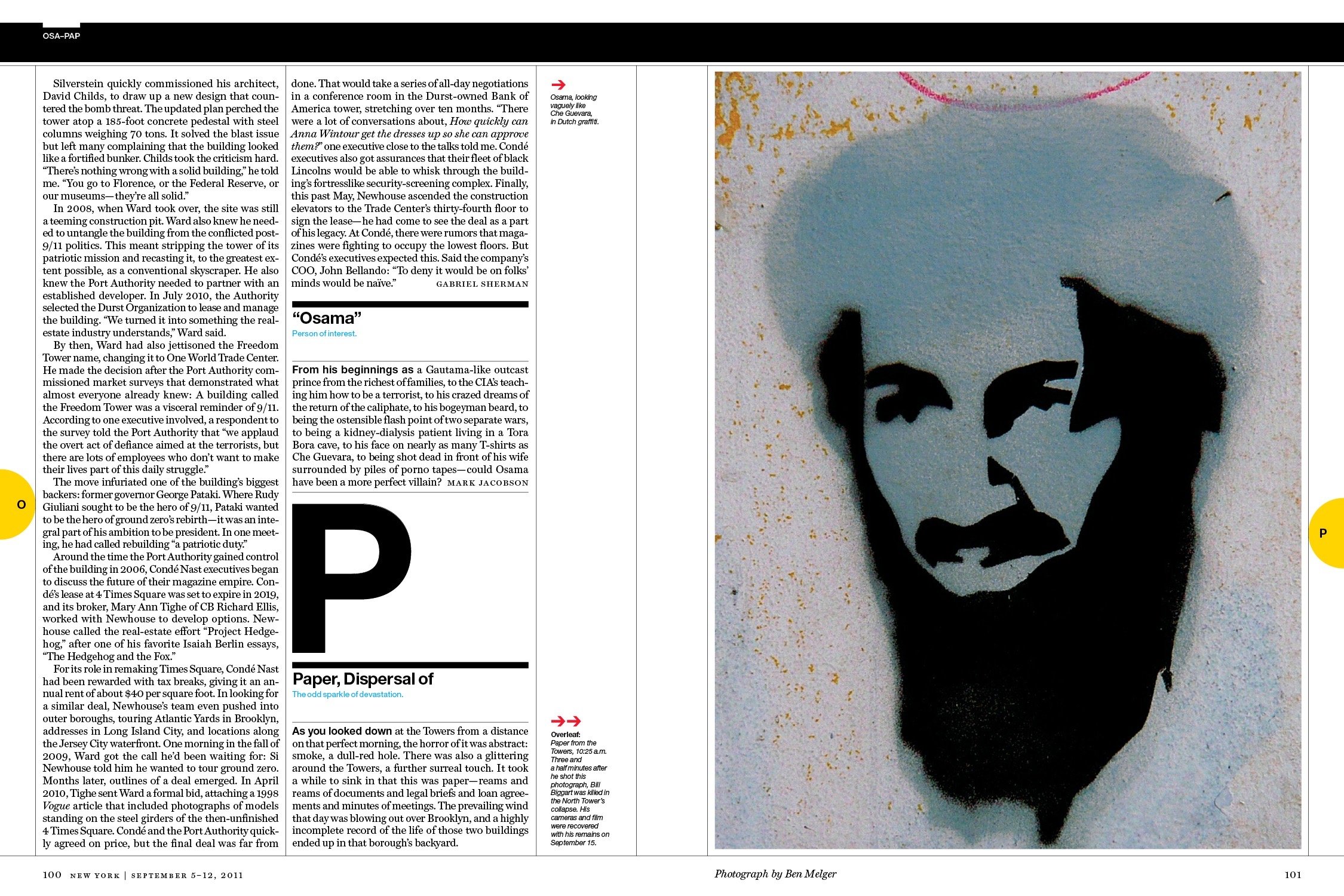

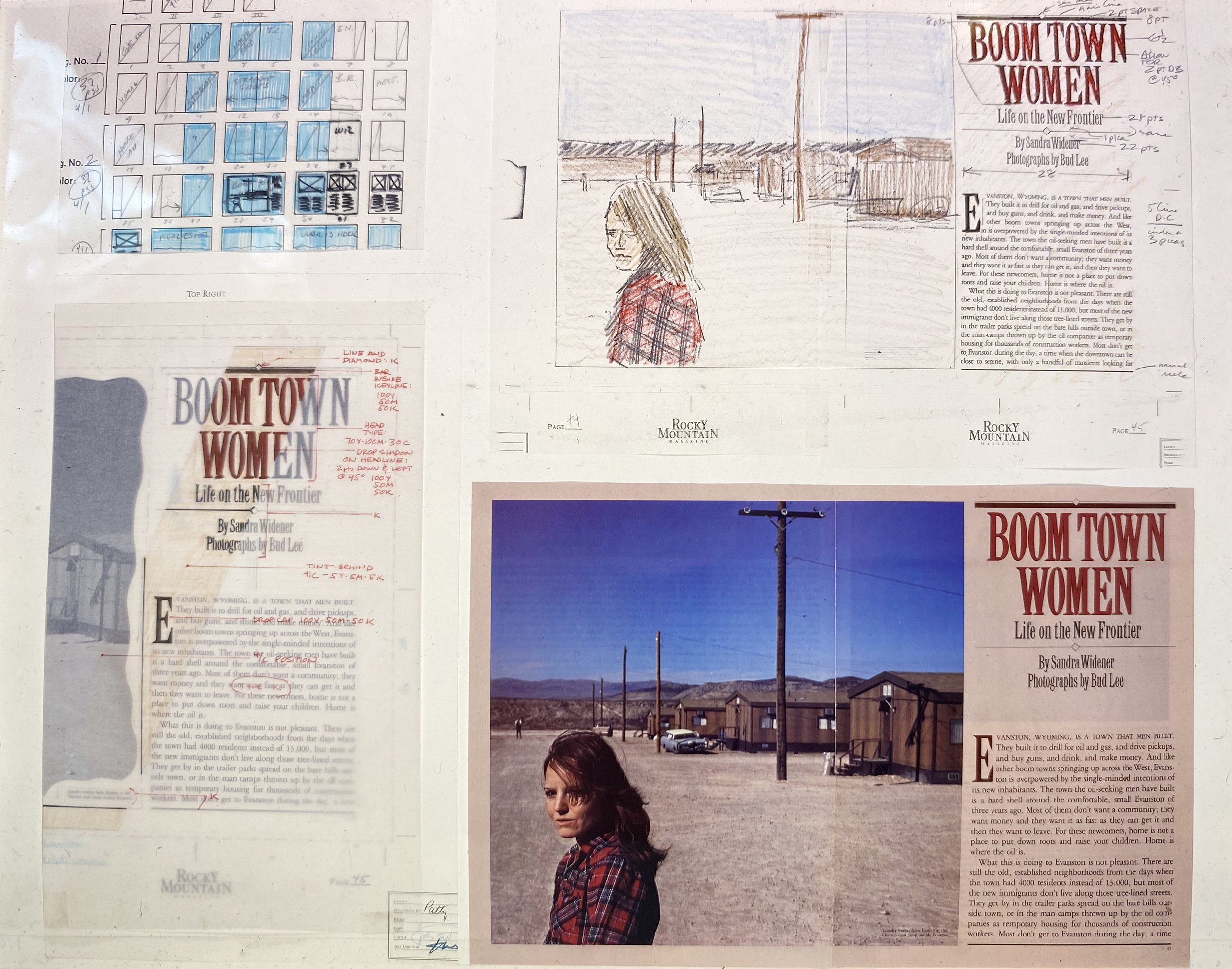

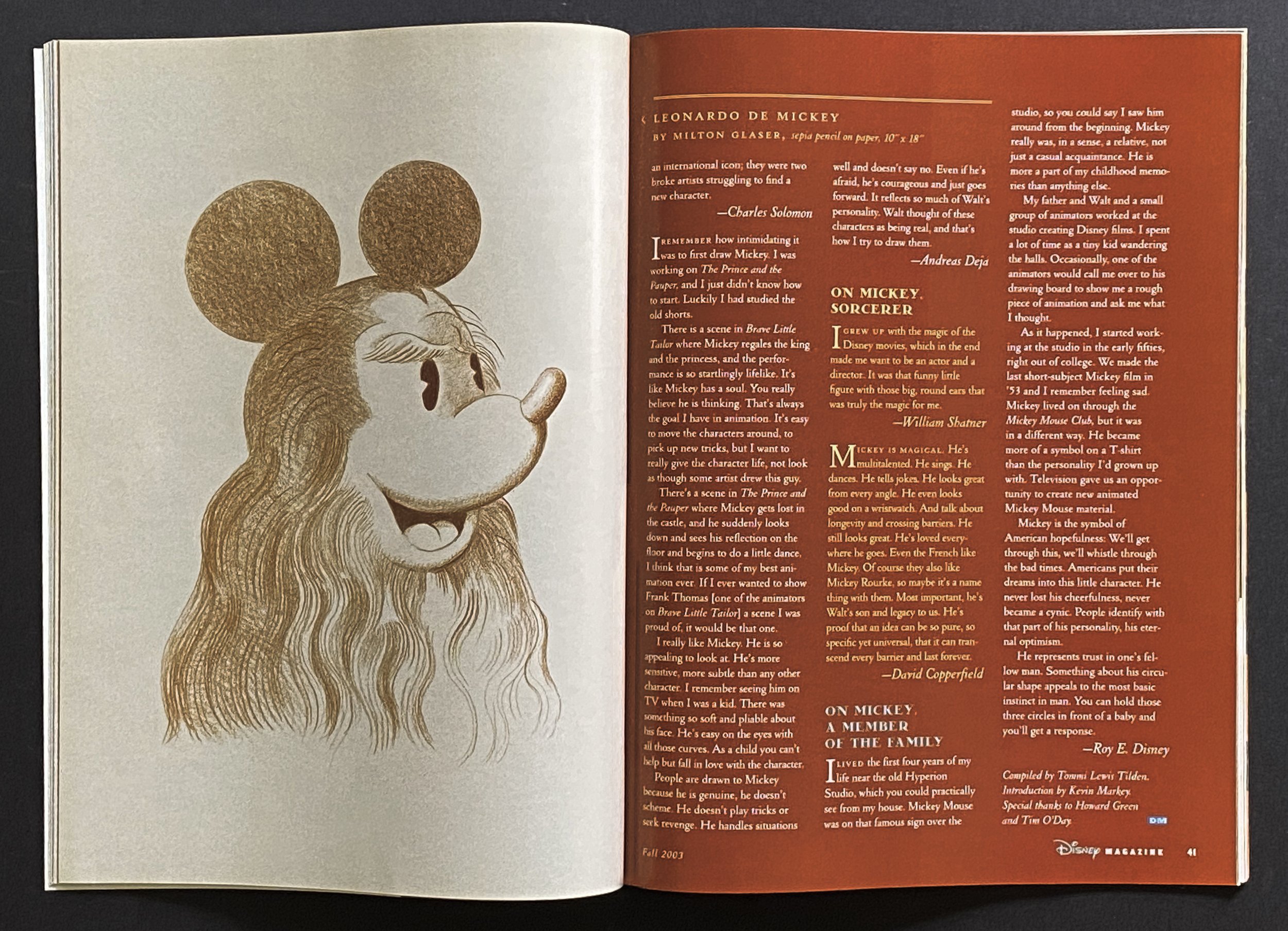

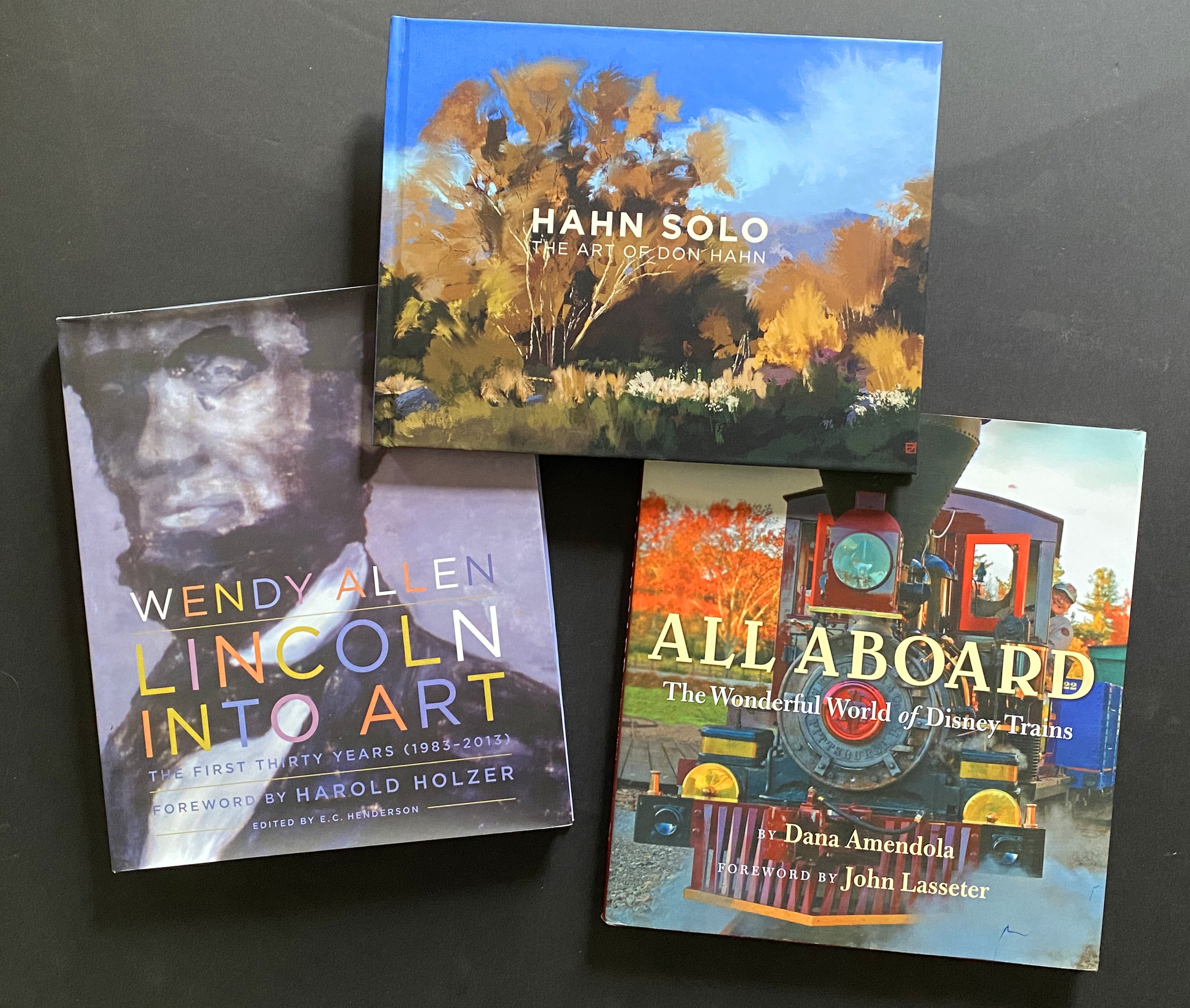

Above, from left: Christopher Holme, Towey, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and Bryan Holme at work on Onassis’ book, In the Russian Style, at the Viking Press in New York, ca. 1977.

Patrick Mitchell: And did you know, when you finished school—I know you went through a process of figuring out that you wanted to become a design major—but did you know after school you were New York-bound?

Gael Towey: Yes. I understood that there was really no other place to have a career in design. And I went to see a vast assortment—I had 30 interviews when I graduated, and I was carrying around that enormous portfolio. You remember those? They were probably 30 inches by 20 inches or something. They were so heavy. And I didn’t have any magazine covers. I didn’t have any book covers. I just had art, you know, I had silkscreens, and photographs, and illustrations, and some typographic treatments on silkscreen. It’s pathetic.

No wonder I had 30 interviews! I only had one job offer.

Patrick Mitchell: What was the first job interview you went on?

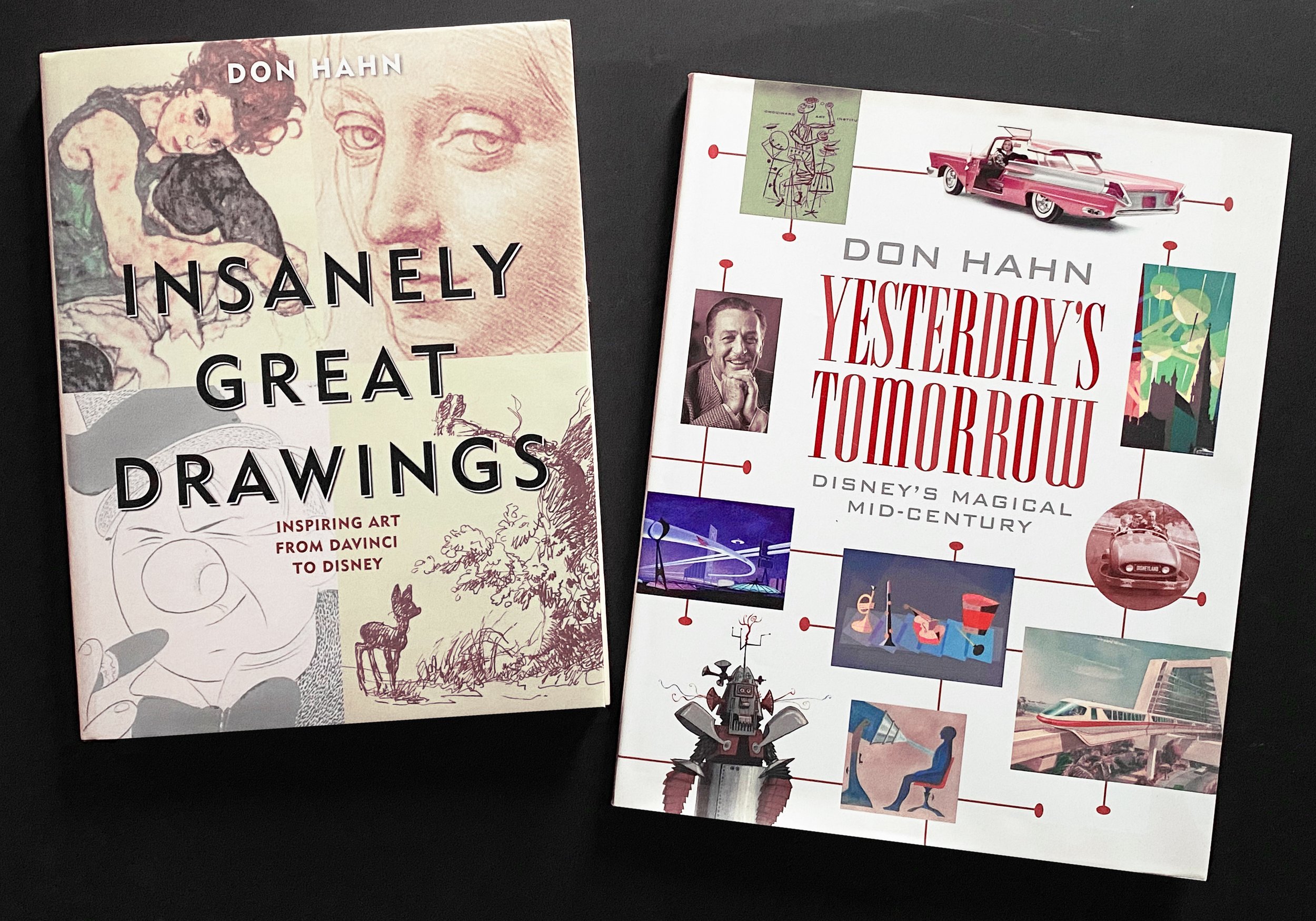

Gael Towey: Oh, I don’t remember the first job interview. I think Grey Advertising actually did offer me a job. So I was choosing between Grey and Viking. And, I don’t know, I guess what intrigued me about Viking Press was the books.

The books were so beautiful. There were art books and museum catalogs and so on. It was a very impressive place.

Patrick Mitchell: Was there a job that you badly wanted but didn’t get? Like, a heartbreaker?

Gael Towey: No. I just didn’t know anything about the business. Stephen, my husband, as you guys know, went to Cooper Union. And he was taught by Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast—all of these really famous designers and illustrators, and they gave him jobs and he knew everything about the business because he lived in New York City.

Patrick Mitchell: He was a thoroughbred.

Gael Towey: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: He didn’t have to hit the pavement.

Gael Towey: No.

The Martha Diaspora

Debra Bishop: Gael, your early career path kind of seems like a prescription for ending up as a creative director at a place like Martha Stewart Living. Perfect experience. Perfect timing. How did all that happen? Was it karma? Luck?

Gael Towey: Yeah, it was luck. And I’m a hard worker. It never bothered me that I was essentially a mechanical artist. These are the days of getting lino proofs and using rubber cement and all of that. I was just so happy to be in the room.

You know? It’s New York. It’s 1975. It was an extraordinary place to be. I couldn’t believe that I was in New York City. It was fabulous.

Patrick Mitchell: Before you landed at Martha Stewart, you spent a year at Condé Nast, where you say you learned what not to do. Safe to say you were not terribly fond of Conde’s notorious editorial director Alexander Liberman. What happened there?

Gael Towey: Well, Nancy Novogrod was the editor in chief, and I knew her because she worked at Clarkson Potter Publishers. And so we’d known each other and worked together on many books. And we did a lot of decorating and cookbooks at Clarkson Potter, so she knew my background.

And she hired me to be art director when she became the editor in chief after Anna Wintour, who redesigned House & Garden magazine. But Alex Liberman was the editorial director of Condé Nast at the time, and he was at the end of his career. He was very old, and crotchety, and power hungry. And, the system was that if you were an editor, you were not allowed to talk to me as the art director. I was isolated in what they called a “layout room” and it was thought that if the editors came in to hang out, they would influence me in choosing photographs and doing layout. So I would spend the day by myself.

It was a lonely existence. And then Alex would take me to La Grenouille for lunch, and we’d be surrounded by gorgeous flowers, and he’d point out all the fancy people that were there, and we’d eat frog legs or whatever. And we’d come back to the office, and I would show him my layouts and he would literally tear them up! And he’d say, “We can’t do this!”

And he would get out new layout boards, and shuffle through the photostats, and choose something, and tear pictures in half, and lecture me, and tell me, “We need more castles in this magazine!” The following week was, “We need more kitchens in this magazine!” He would say whatever was the opposite of whatever you were doing.

And it was a pretty brutal situation. And the editors closed their doors. They locked their filing cabinets. They were incredibly competitive. And I asked Martin Filler, who was the architecture critic, how he could stand it, because Martin would routinely be humiliated by Alex Liberman in front of everybody. And I said to him, “Martin, you’re so smart. How can you stand this?” And he said, “Gael, it’s because it’s a fashion company. You go into fashion and out of fashion. And that’s just the way it is.” I thought, “Oh my God, how depressing.”

But when we started Martha Stewart Living, I wanted to have a team. I wanted to be with people. I wanted to have friends. You know, I wanted to have a working relationship with people. I didn’t want to be isolated in some room, and then after they beat you up all day long, you get in your car service and go home.

It was awful.

Debra Bishop: You went from Condé Nast to books. Right?

Gael Towey: No. I was at Viking Press then, then Clarkson Potter.

Debra Bishop: Okay. So that was the last stop before ...

Gael Towey: Yeah. I was only at House & Garden for a year. But at least I understood the rhythm of making a magazine.

So when Martha called and said, do you want to be the art director of this magazine? First of all, I couldn’t wait to get out of House & Garden. Second of all, it’s very rare, as you guys know, to have an opportunity to start a magazine from scratch. And of course I definitely wanted to do that.

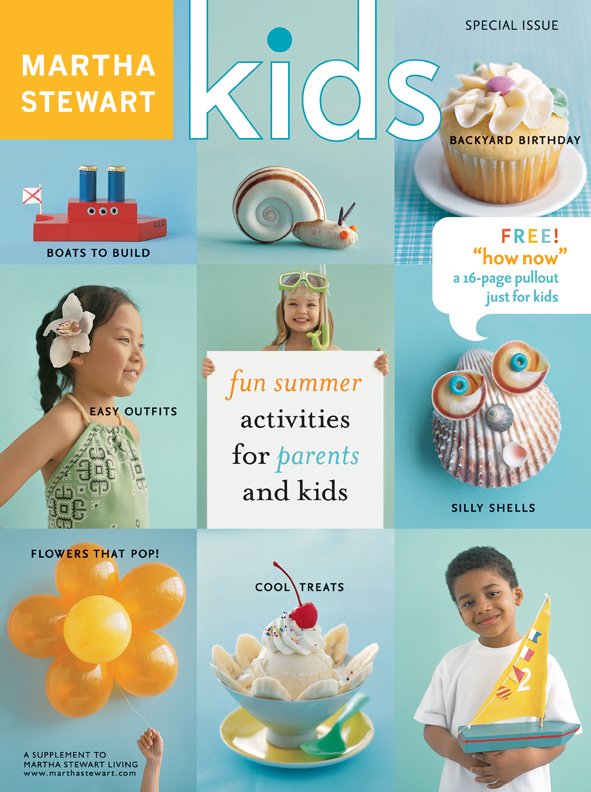

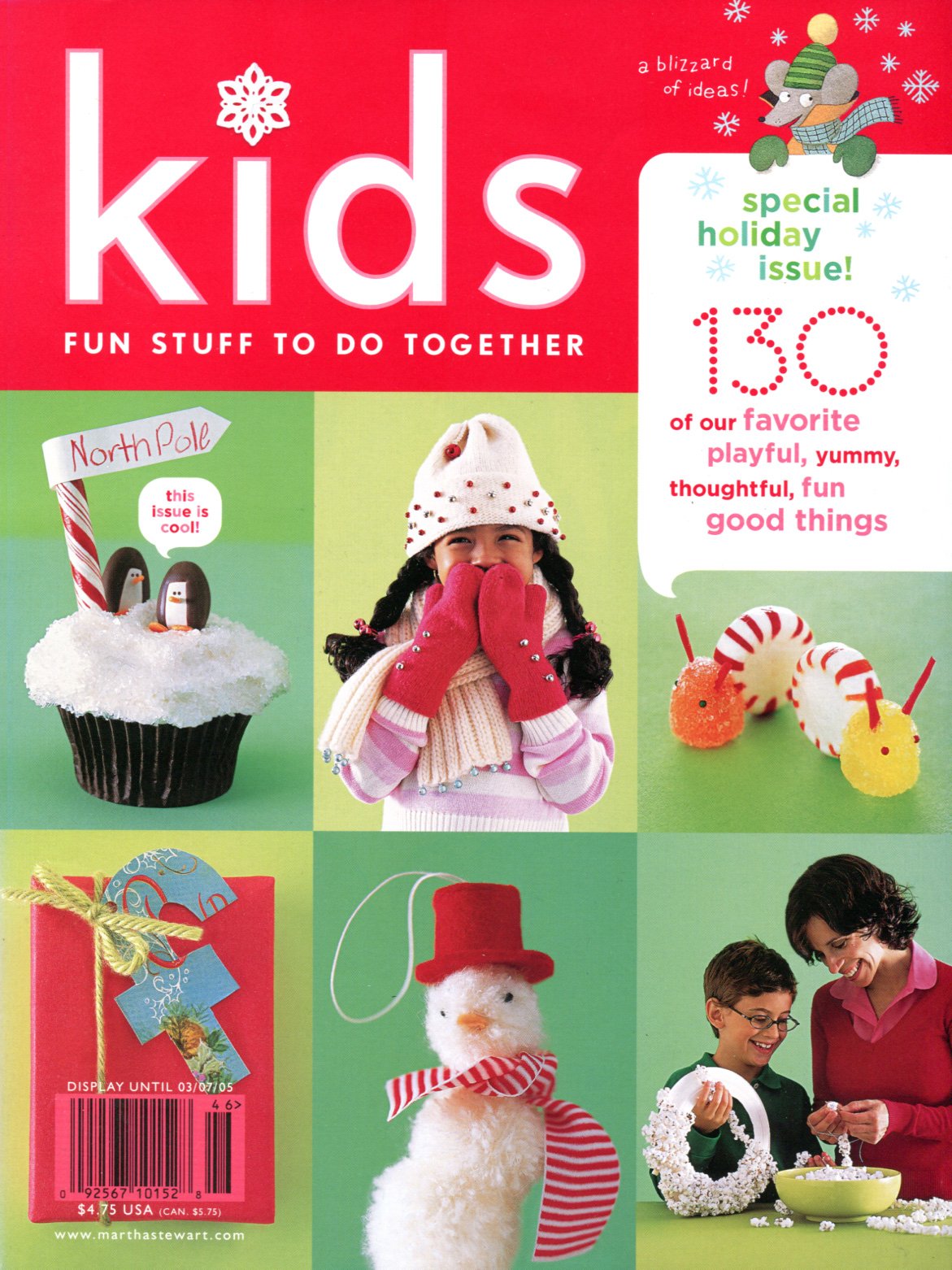

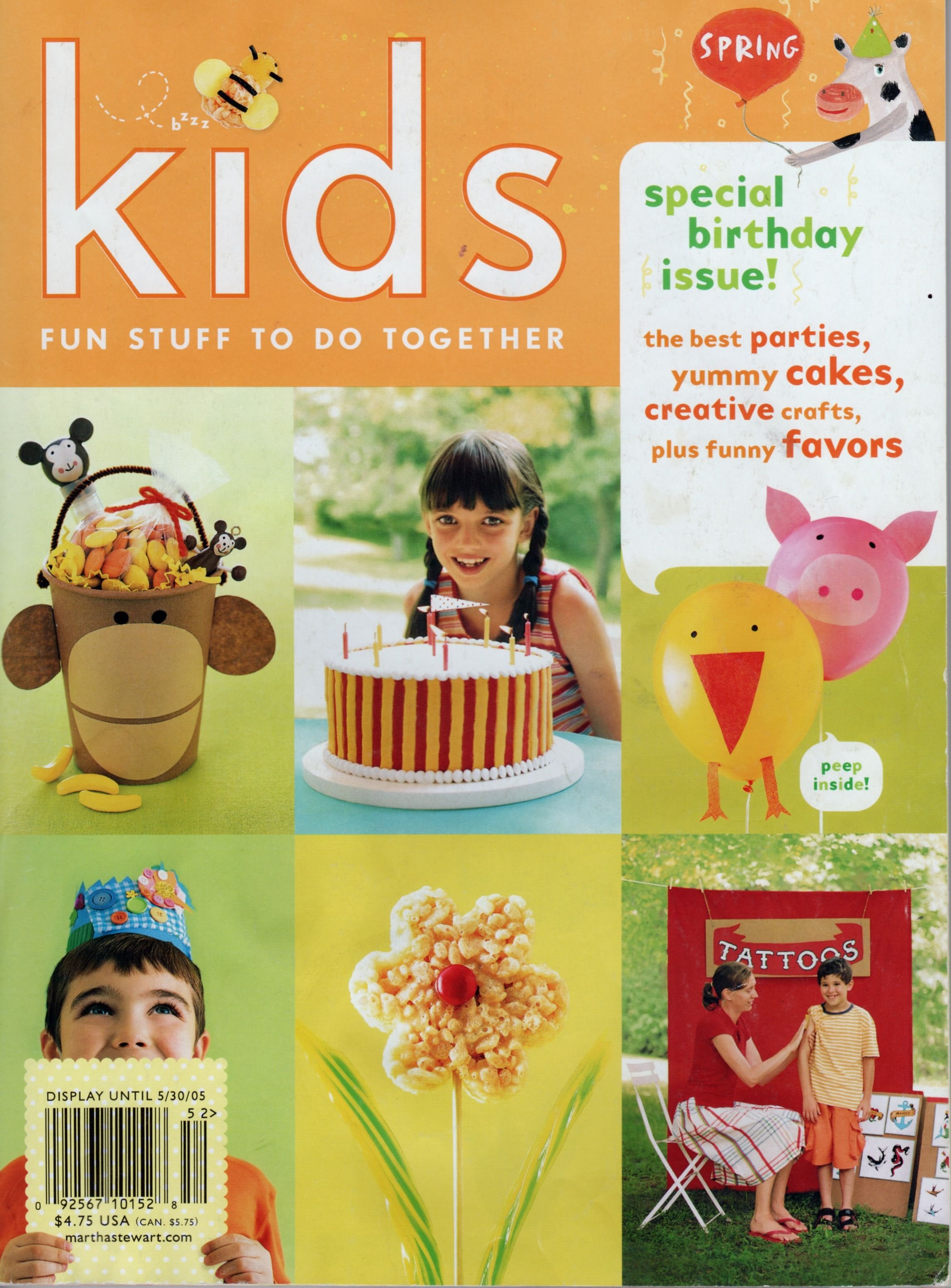

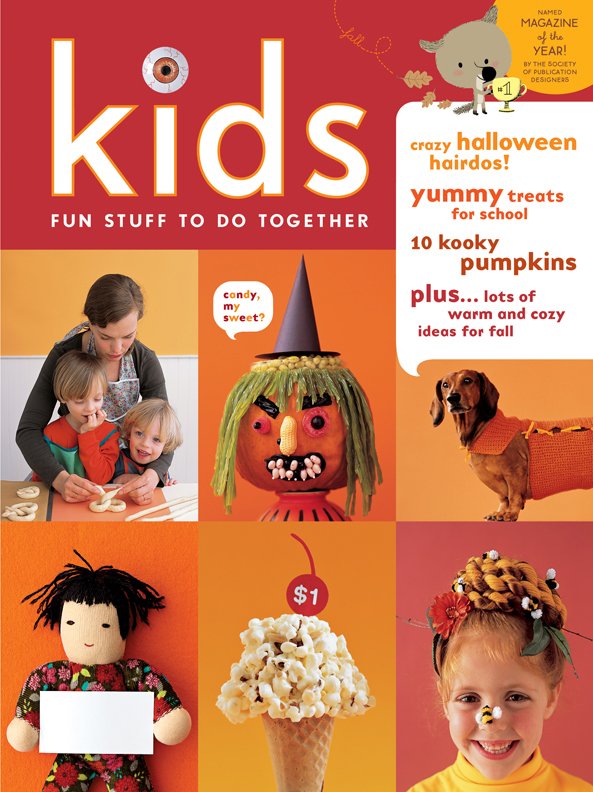

Just like you did, Deb, with Martha by Mail, which wasn’t a magazine, but practically it was a magazine. And Blueprint. And Kids.

“I was very proud of the fact that when you looked down the row of designers sitting at their computers, they would have a stack of art books next to their computer because they were in charge of researching a concept for how to shoot the story.”

Patrick Mitchell: So, you meet Martha Stewart, your future employer, and Stephen Doyle, your future husband while working at the book publisher, Clarkson Potter. Talk about how you met arguably the two most important people in your life.

Gael Towey: That’s very true. They are both terribly important. We did about 50 books a year, and so I had the wonderful opportunity of being able to hire art directors and designers who I admired to do a lot of the books, and I learned so much from them.

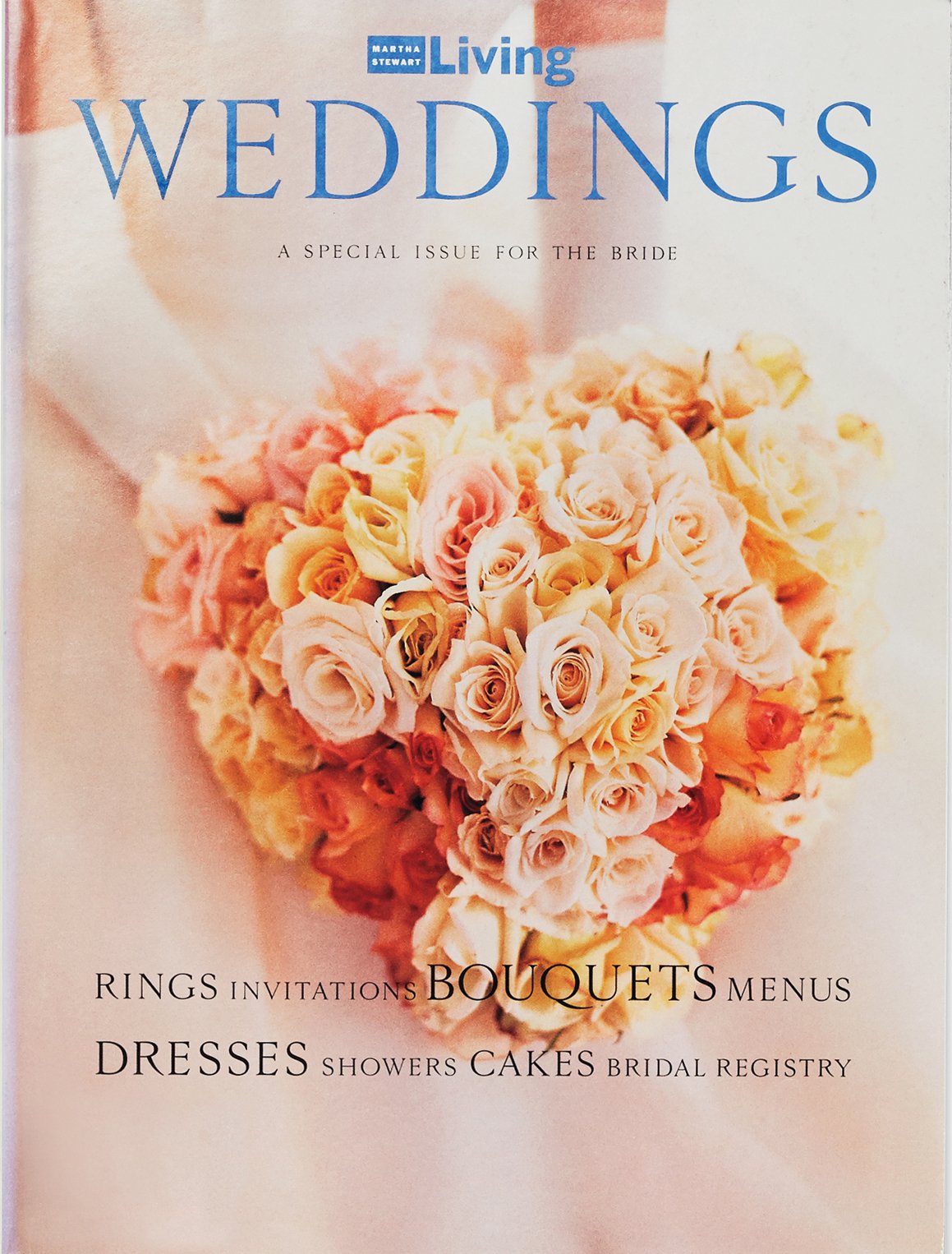

People like Rochelle Udell, and the authors themselves, Susie Slesin and that relationship was really quite fabulous. So that’s where I met Martha and we were about to publish Martha’s wedding book. It was the biggest book of the year. So I started calling around to say, “ Who should I talk to?”

And Mary Shanahan, who was the art director of Cuisine —and really an inspiration for me, she was an extraordinary designer—and she really changed that food magazine market by the way she photographed food and the people that she used to photograph. So I called Mary to ask her for a recommendation and she said, “Well, there’s this guy, Stephen Doyle, who just started his own company. You should talk to him.”

And I also called Roger Black. And Roger said, “Oh, there’s this guy Stephen Doyle, you should go talk to him.” So I called this guy Stephen Doyle, and he came over and he was hysterically funny. He said he wasn’t interested in weddings and he didn’t want to design a wedding book.

I was in the middle of a separation from my first husband and I was in a state of severe anxiety. And losing weight and, like, an incredible, nervous wreck. But I really liked Stephen’s portfolio and I really liked his personality. So I said, “Well, we’ll work together on something, even if you don’t want to do this book.”

And I picked my business card up off of my desk and I looked at it and it said, “Gael Dillon.” And I was like, “Oh shit, I have to get new business cards!” And I leaned over the desk and scrubbed out Dillon with my pen, like viciously. And then wrote in there, Towey, which is my maiden name, and I handed it to Stephen and he thought that I was coming onto him, basically. And he thought, “Wow, that’s, you know, kind of amazing.”

I’m not really like that. I’m not a forward person, but we found something to work on together.

Patrick Mitchell: ... and her name is Maud [Towey and Doyle’s daughter]...

Gael Towey: Yeah, exactly! And Stephen had a fake name that he would, if he called, and he was “Pierre,” that meant that it was Stephen asking for a date. And if he called and it was “Stephen,” it meant Stephen, this was calling about doing a job for us.

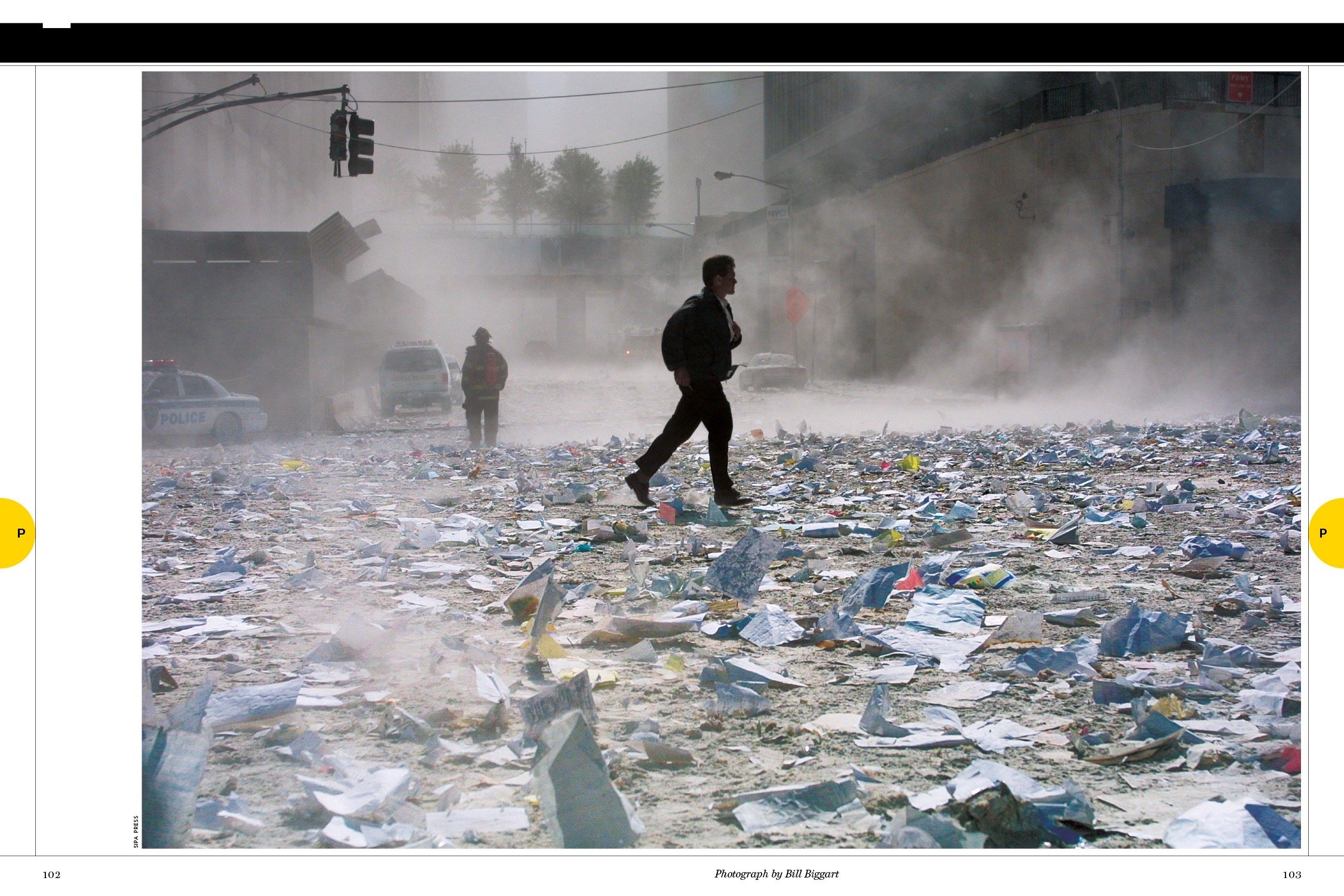

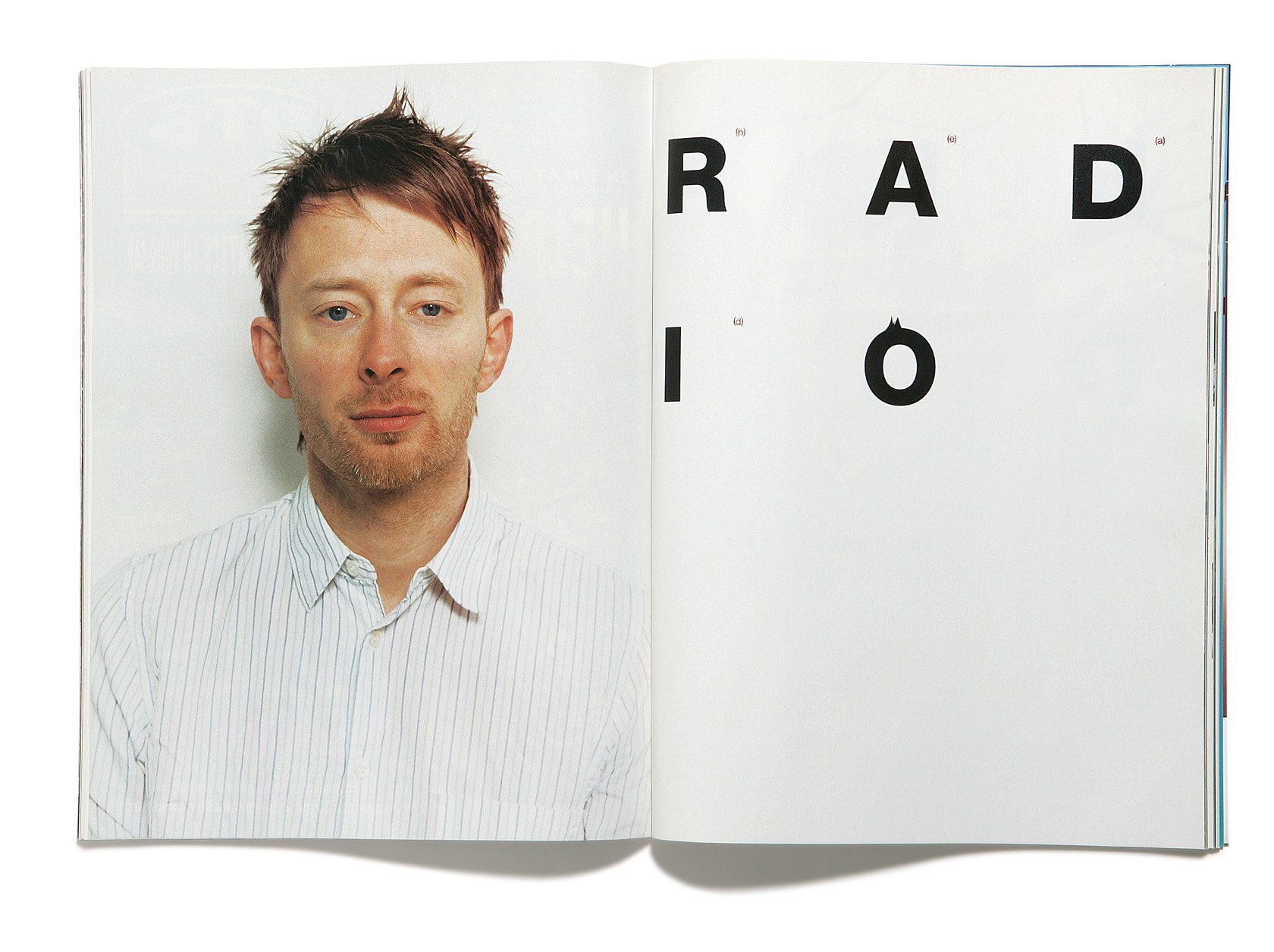

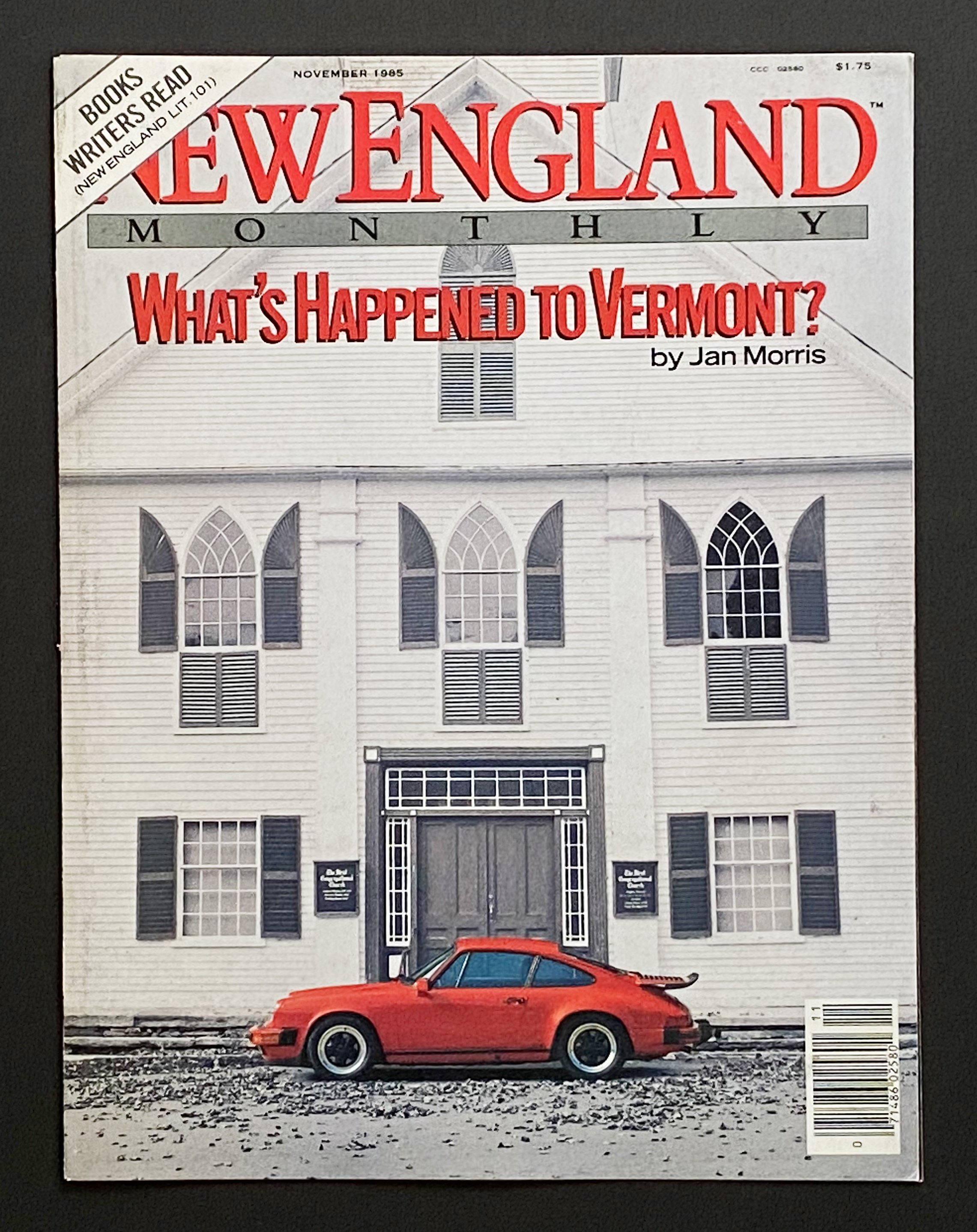

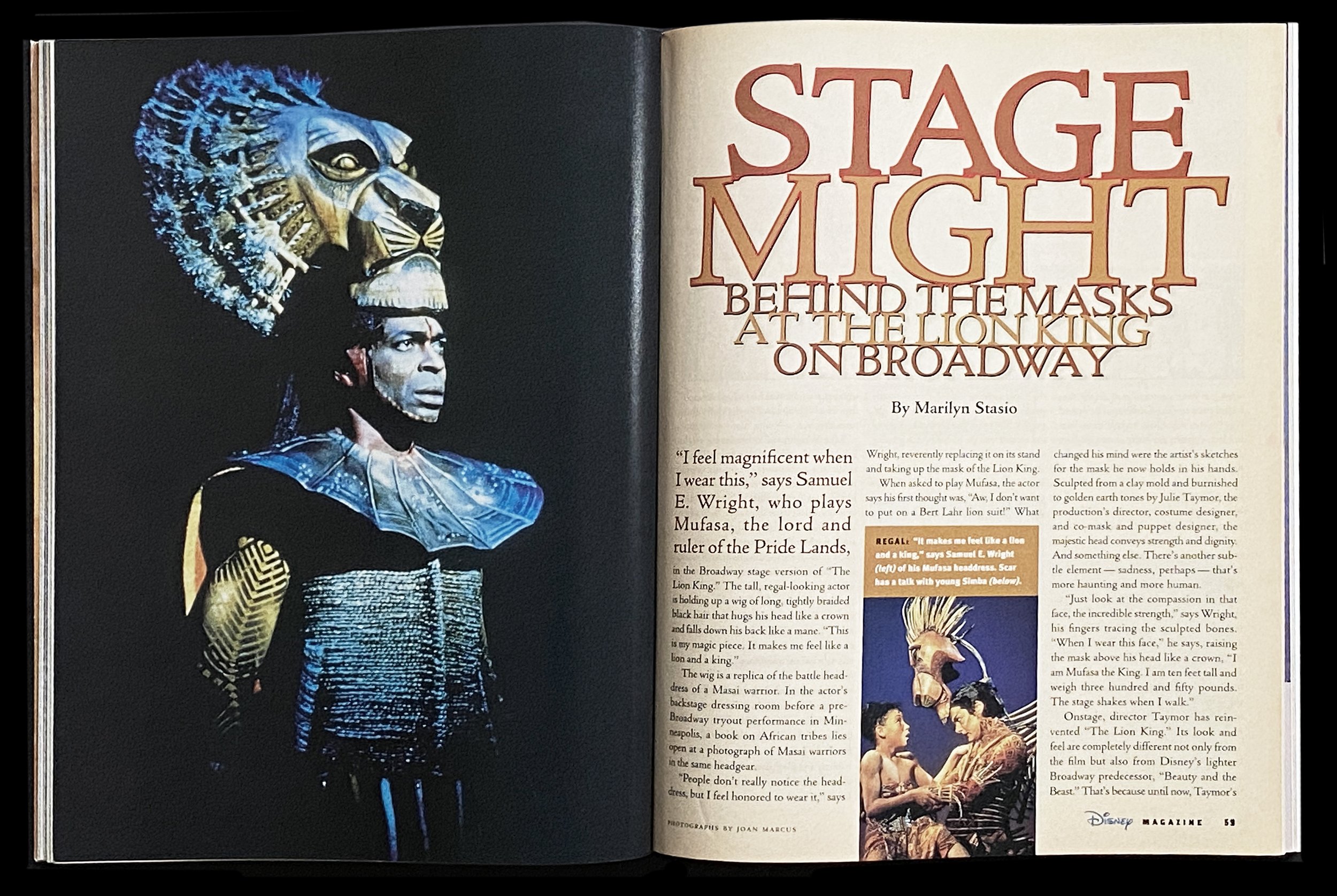

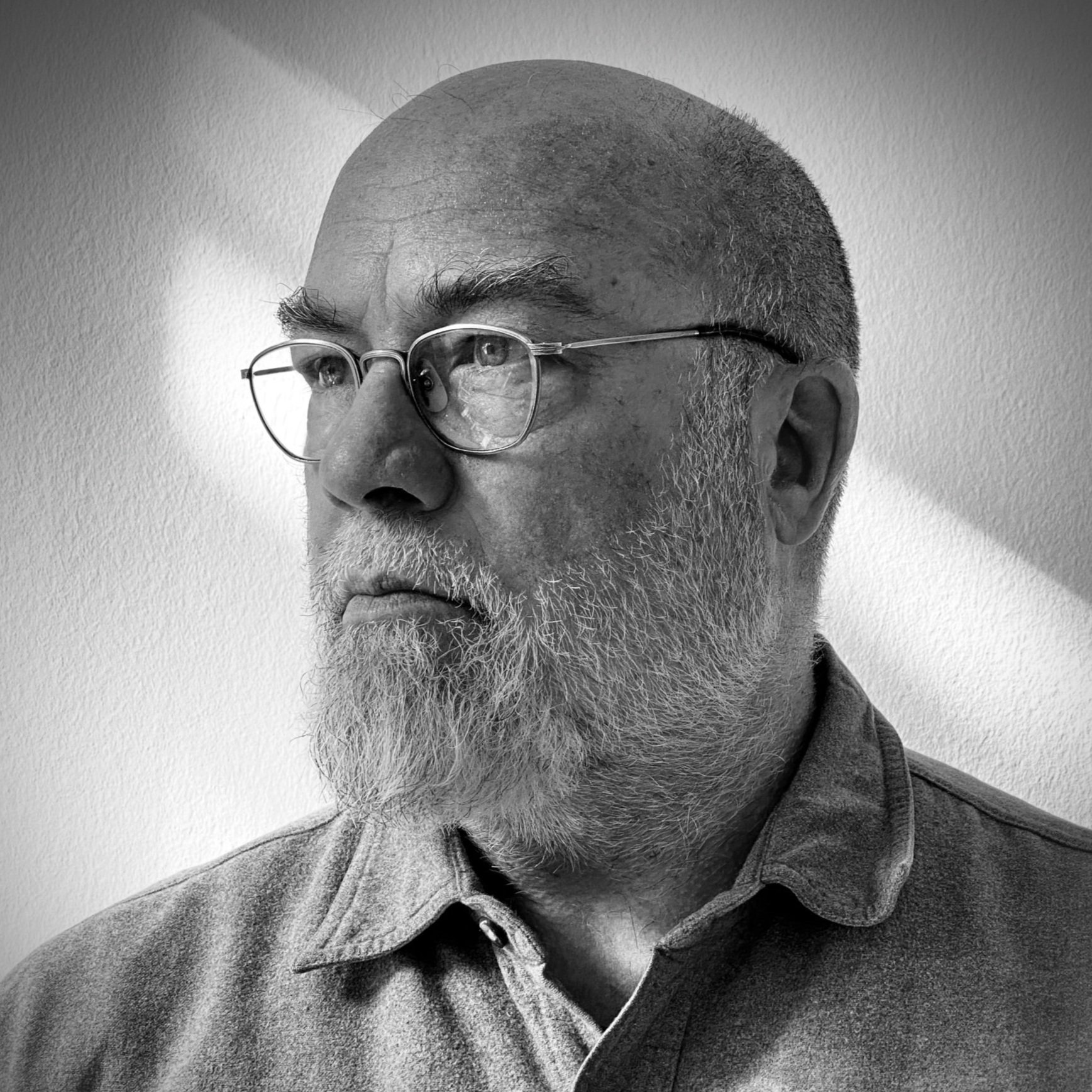

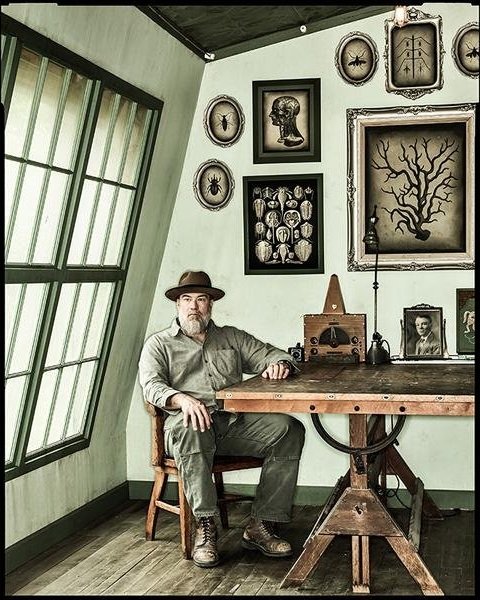

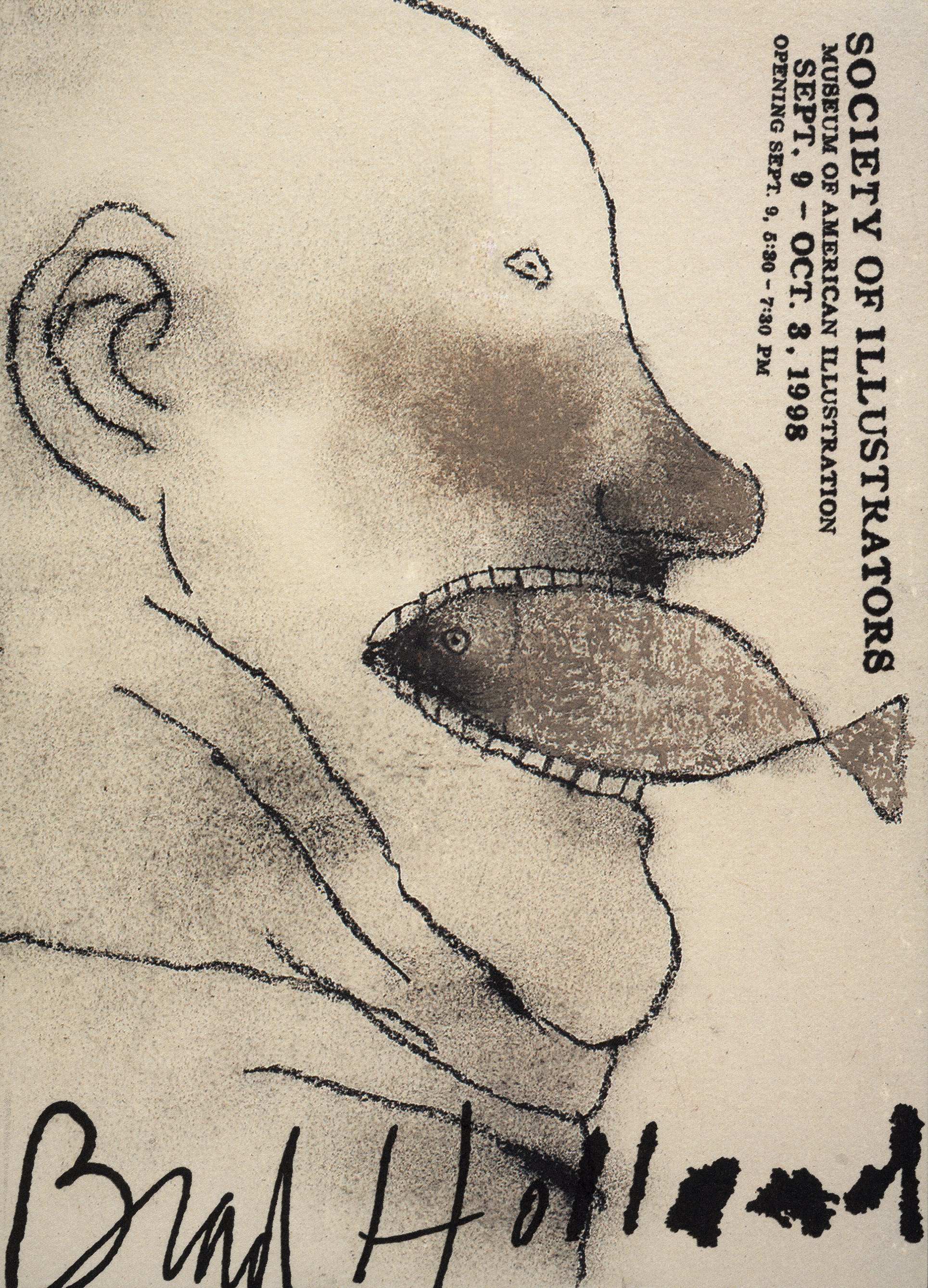

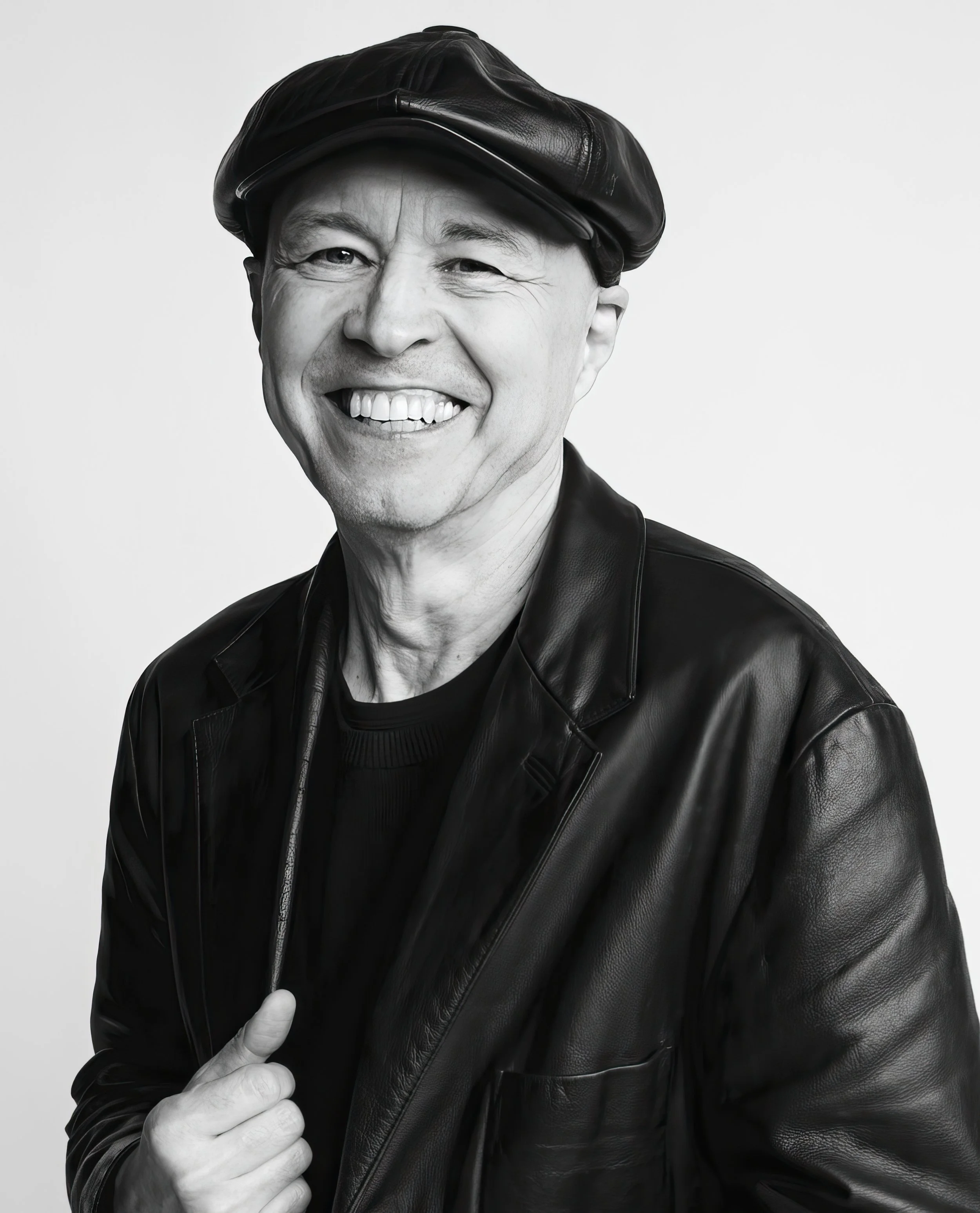

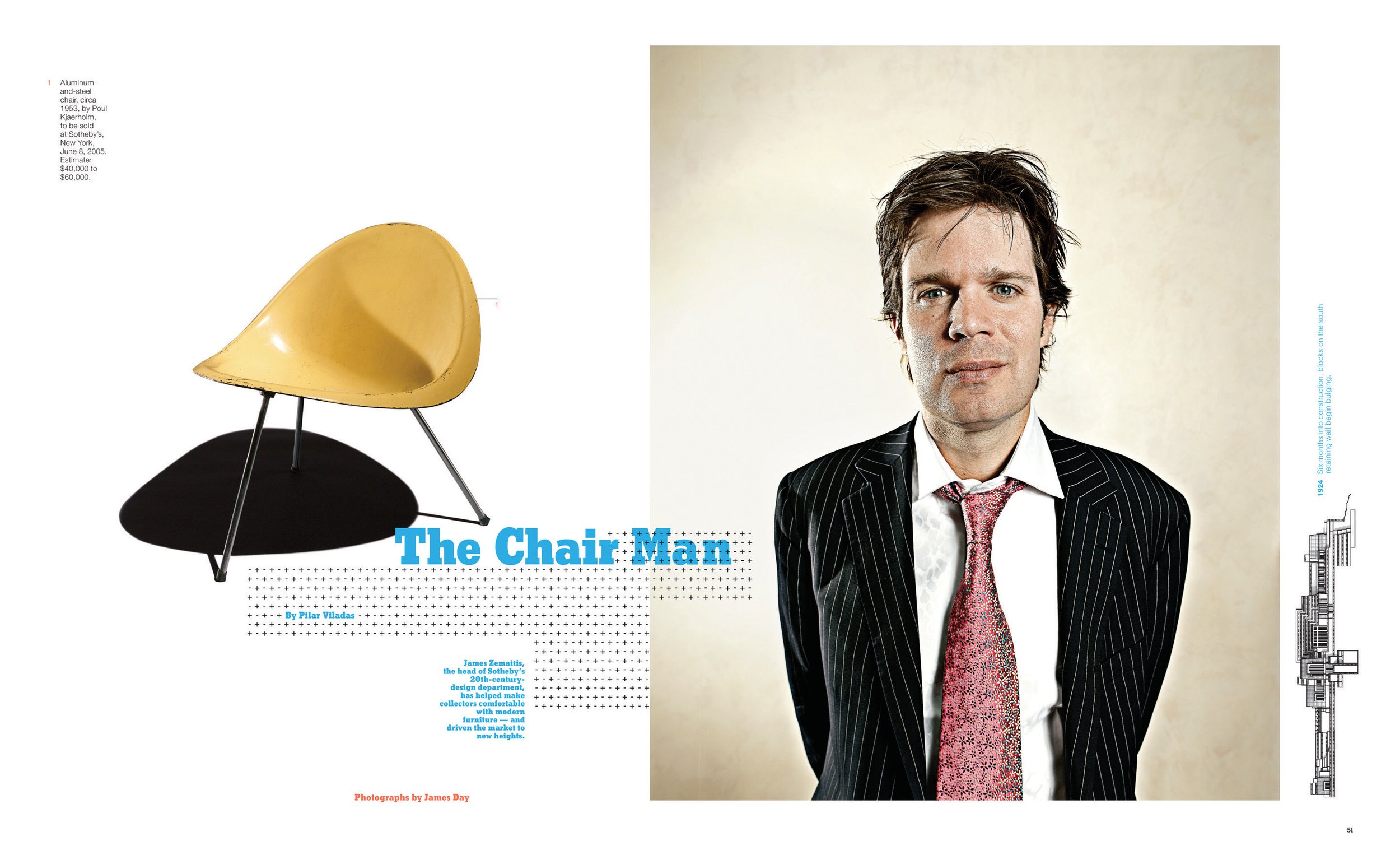

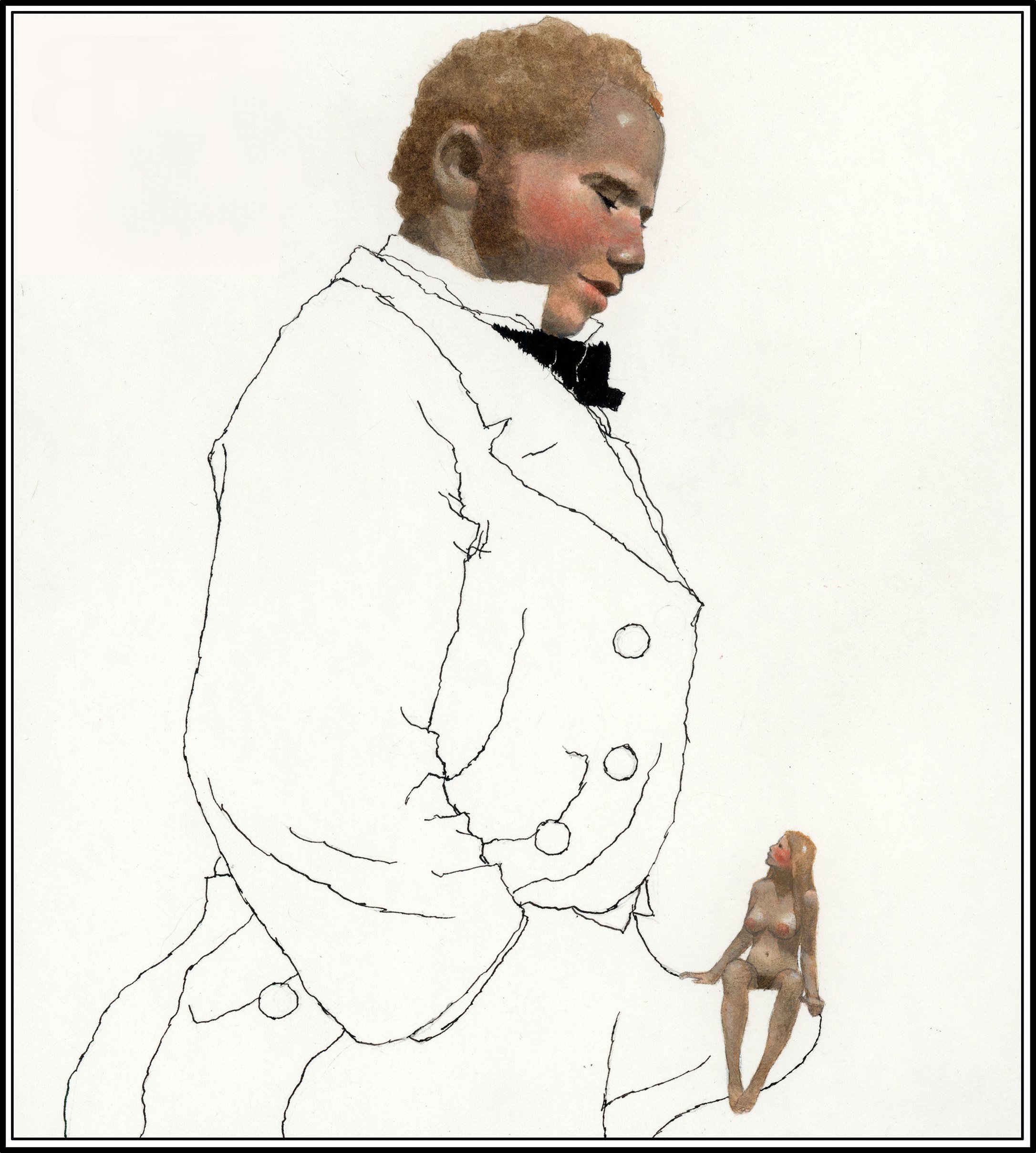

Towey with her husband, designer Stephen Doyle.

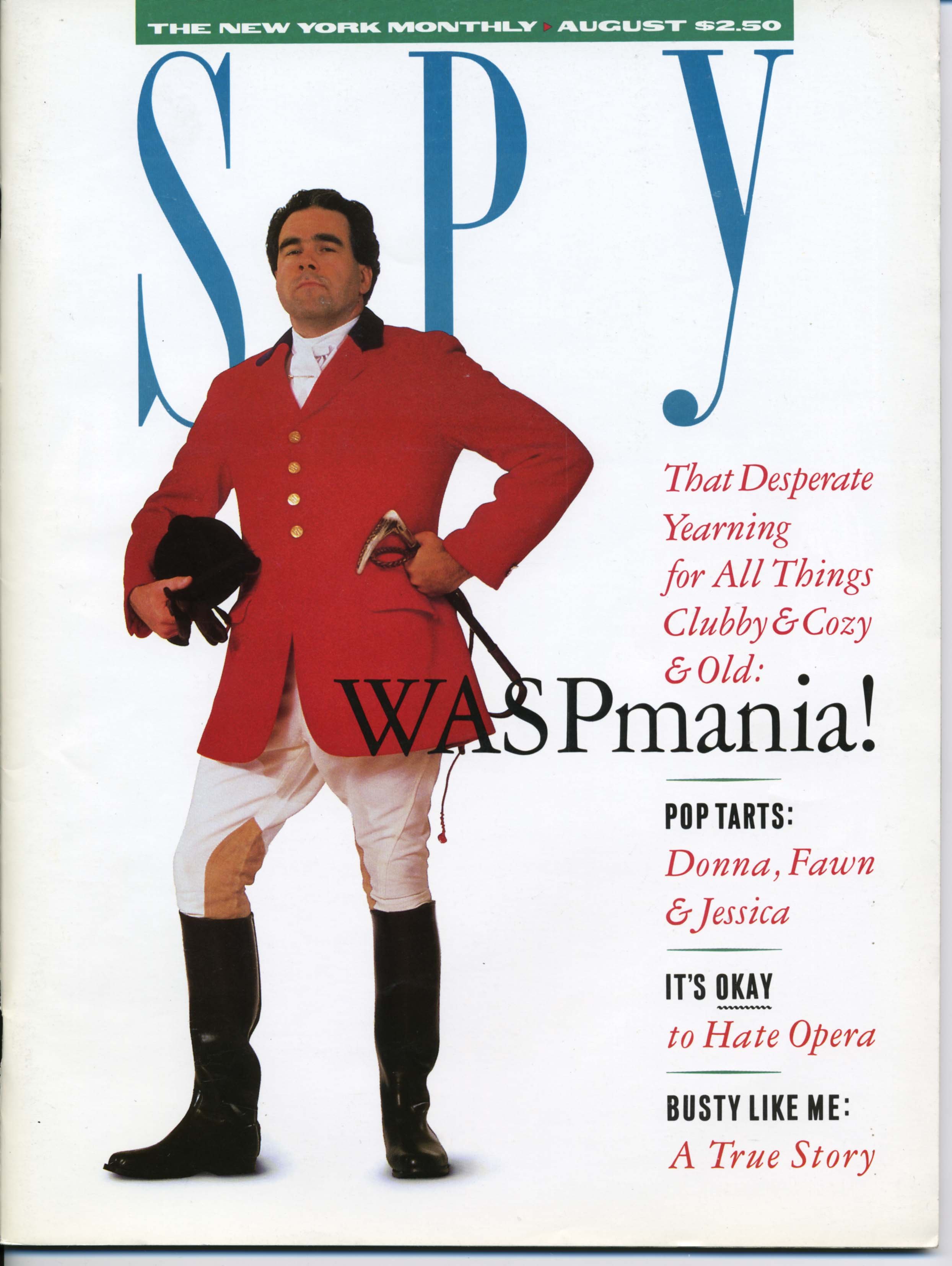

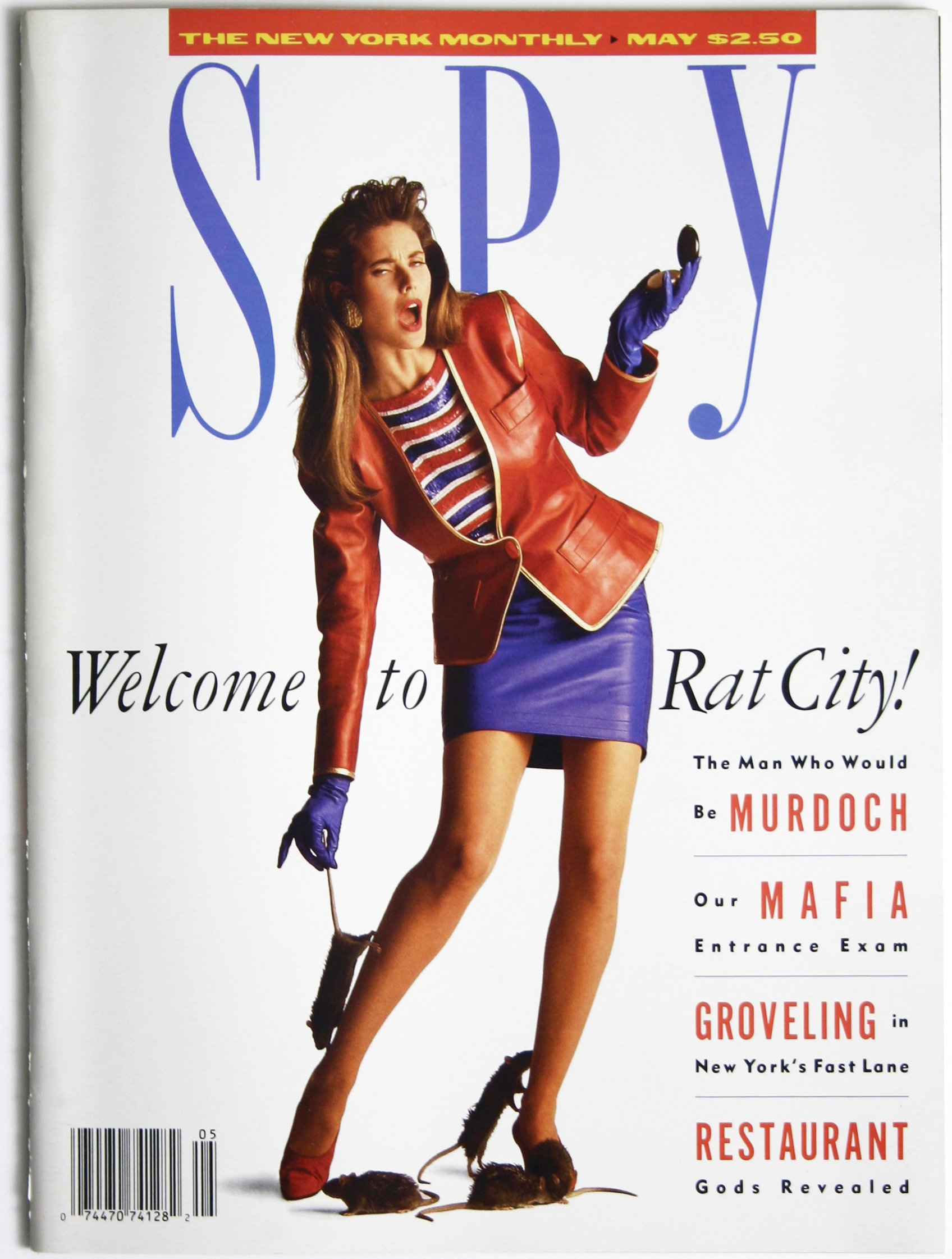

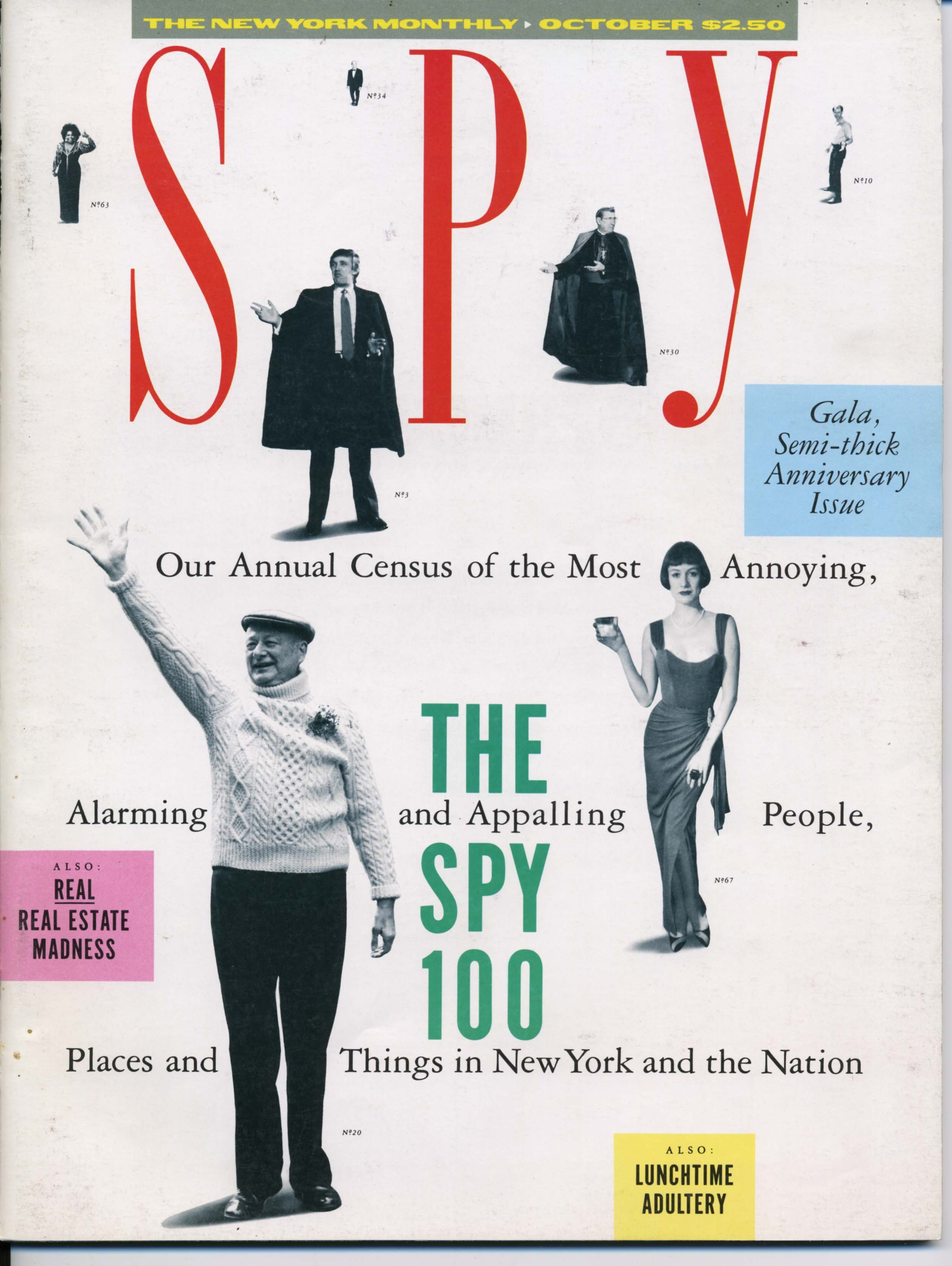

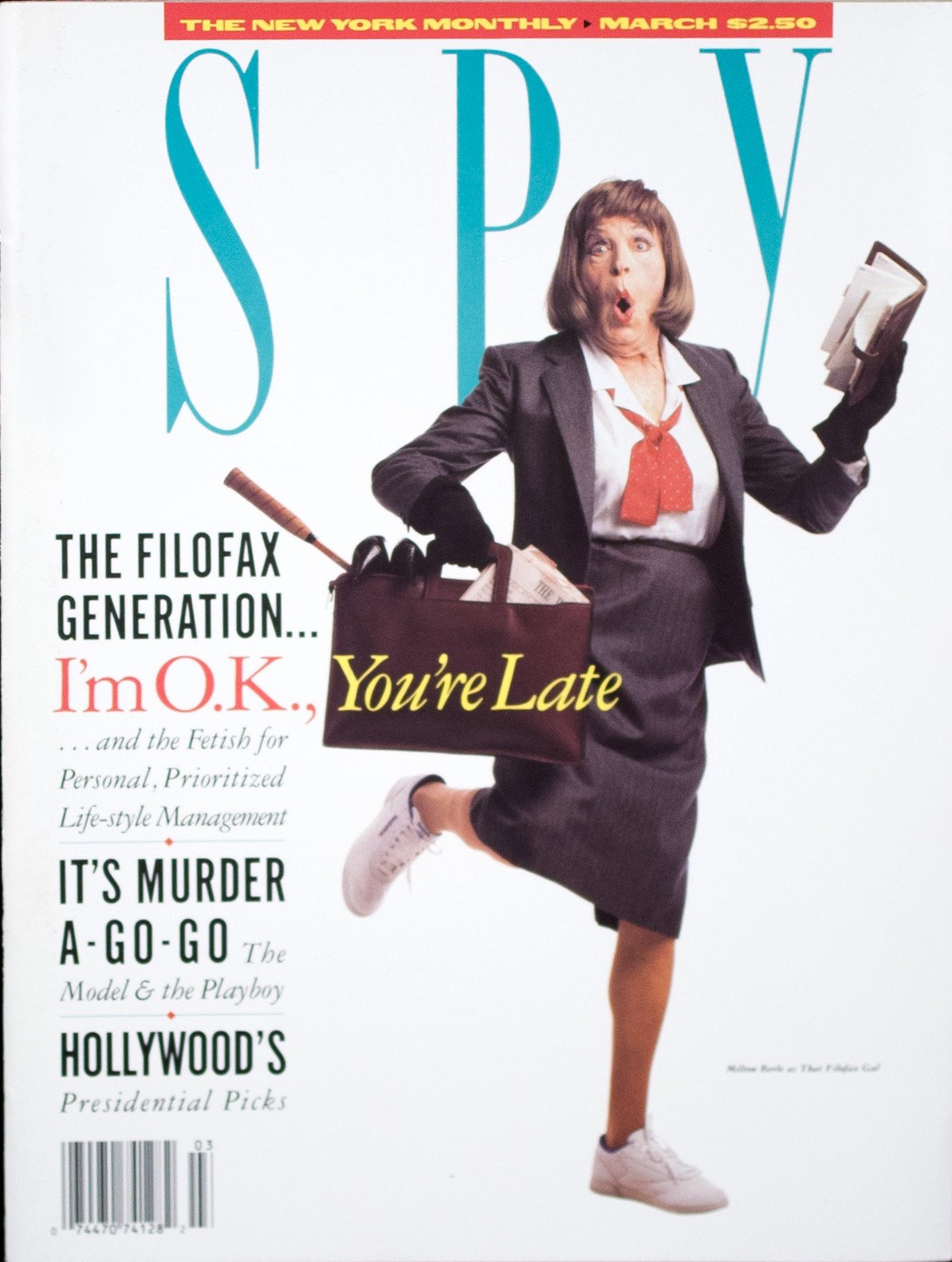

Patrick Mitchell: So you launched Martha Stewart Living in 1990. What were the hot magazines at that time? Who was your competition?

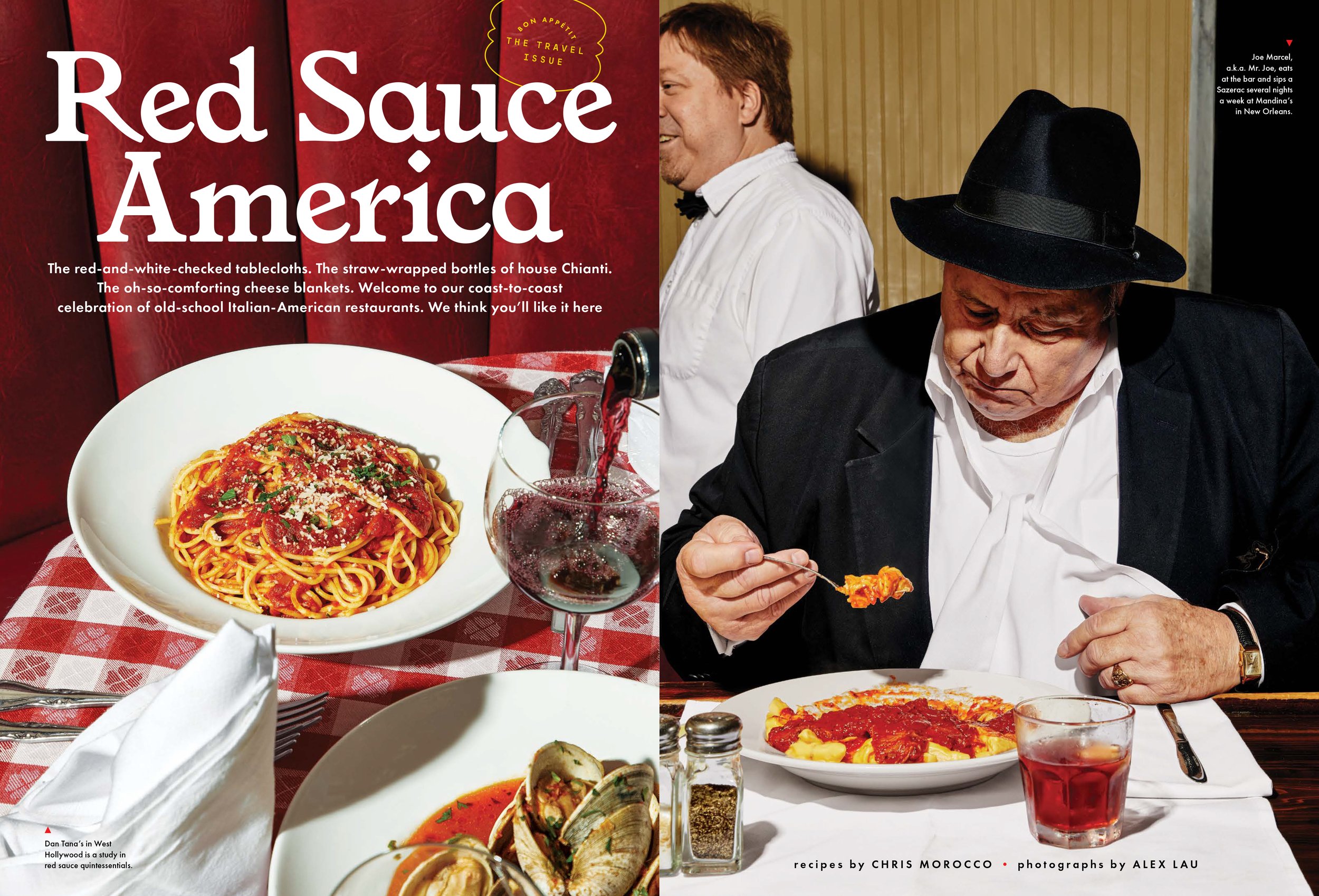

Gael Towey: The “Seven Sisters” [Better Homes and Gardens, Family Circle, Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Redbook, Woman’s Day] were the competition. The other women’s magazines, like Good Housekeeping, and those kinds of things. Cuisine had been bought by Condé Nast and closed because they didn’t want competition and people were sent Gourmet [in its place]. And for those of you who can remember, Gourmet was a very, very stuffy, old fashioned kind of shellacked-looking magazine at the time, in terms of food photography.

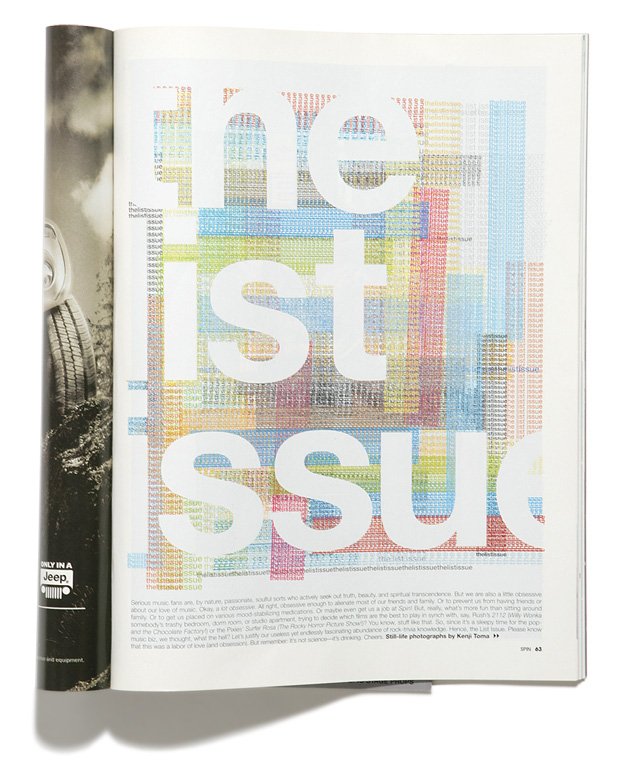

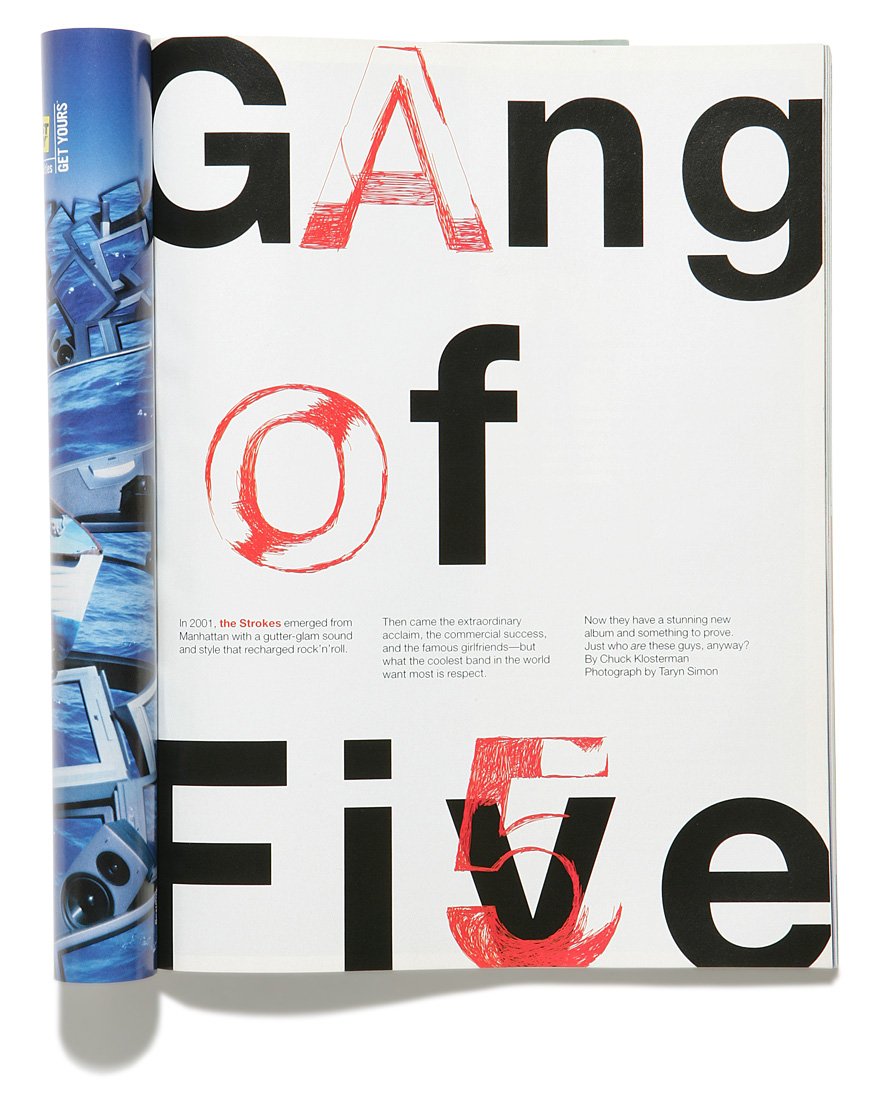

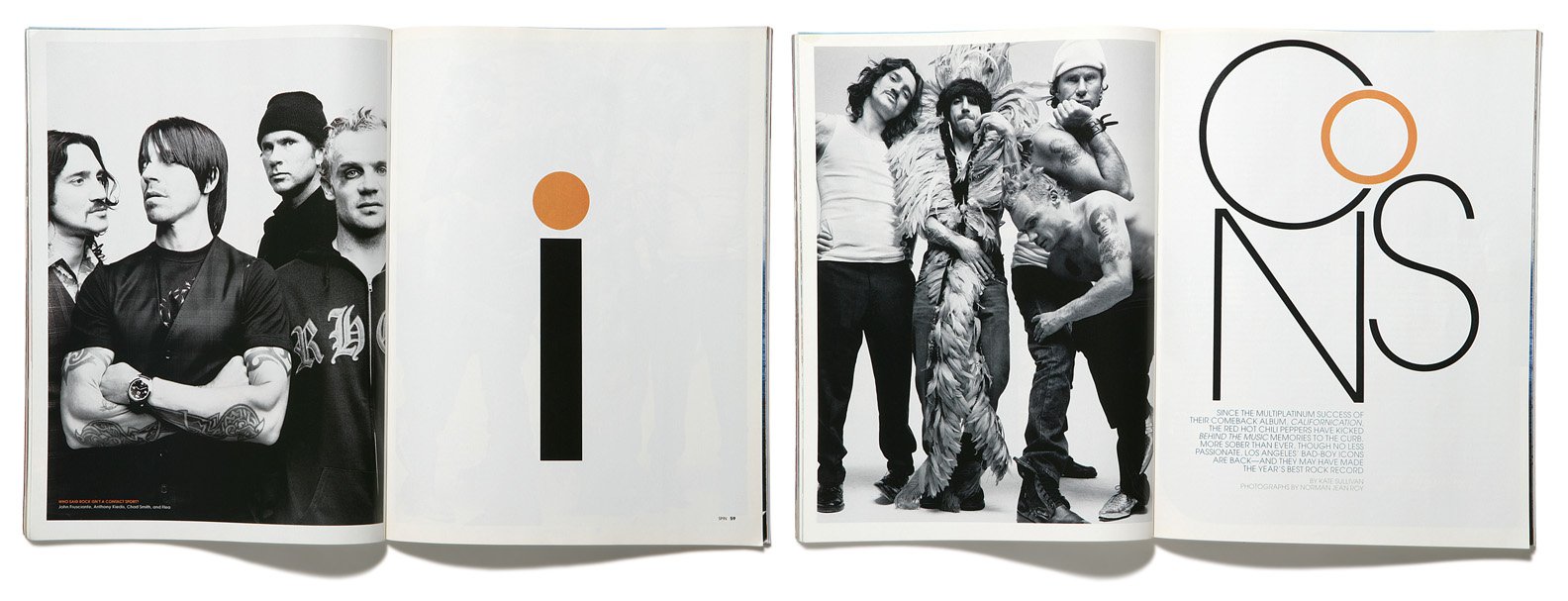

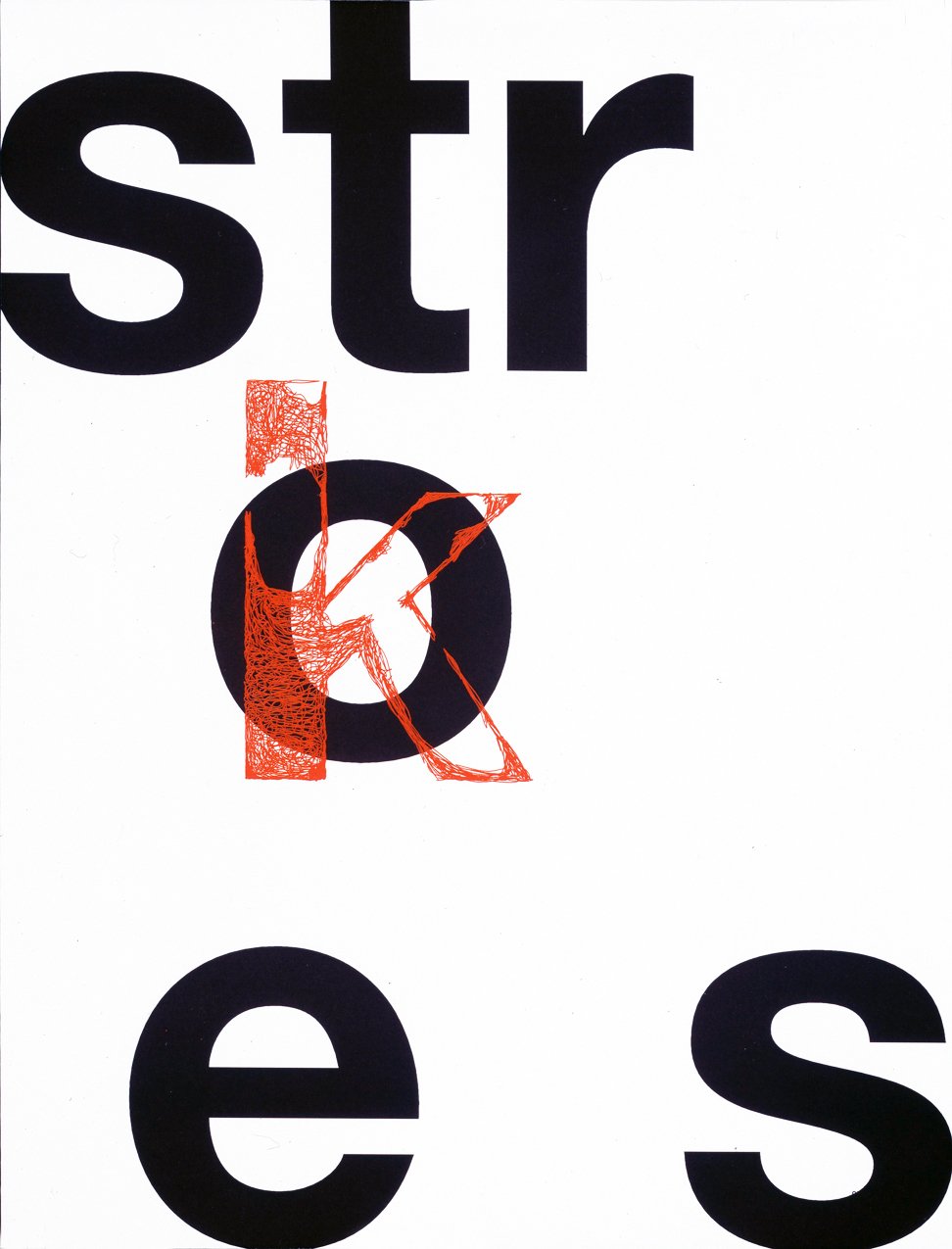

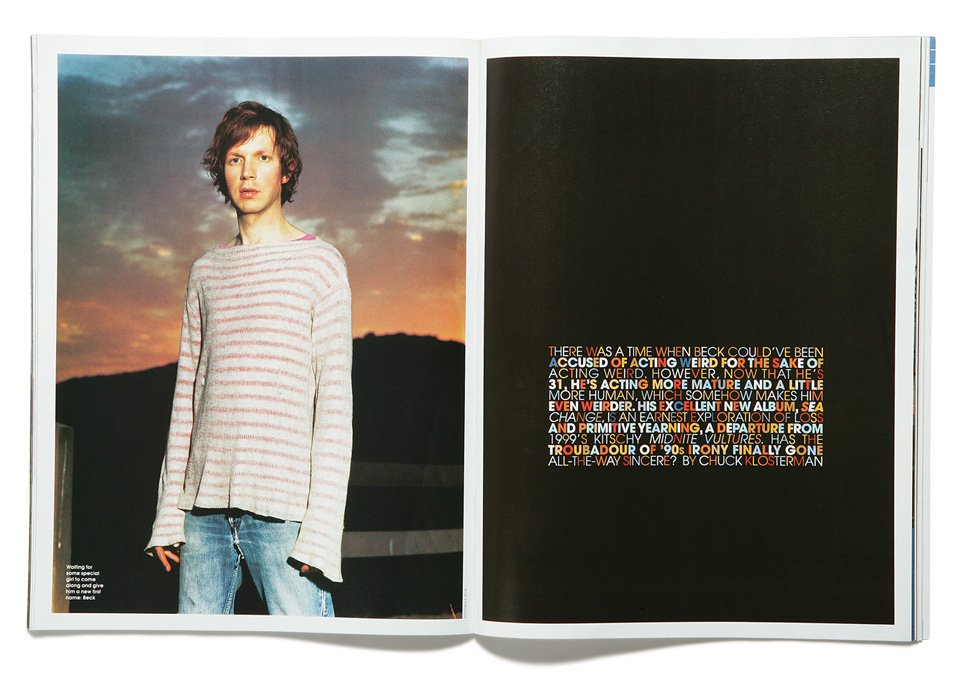

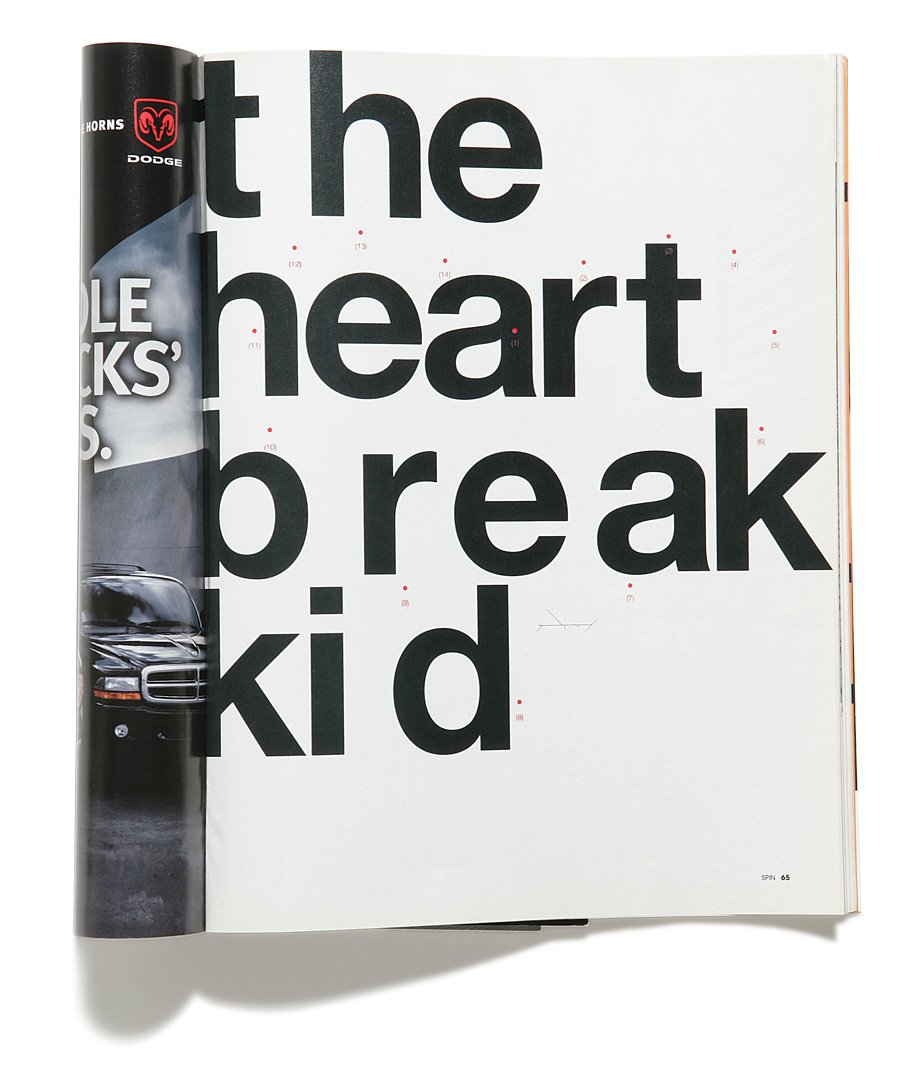

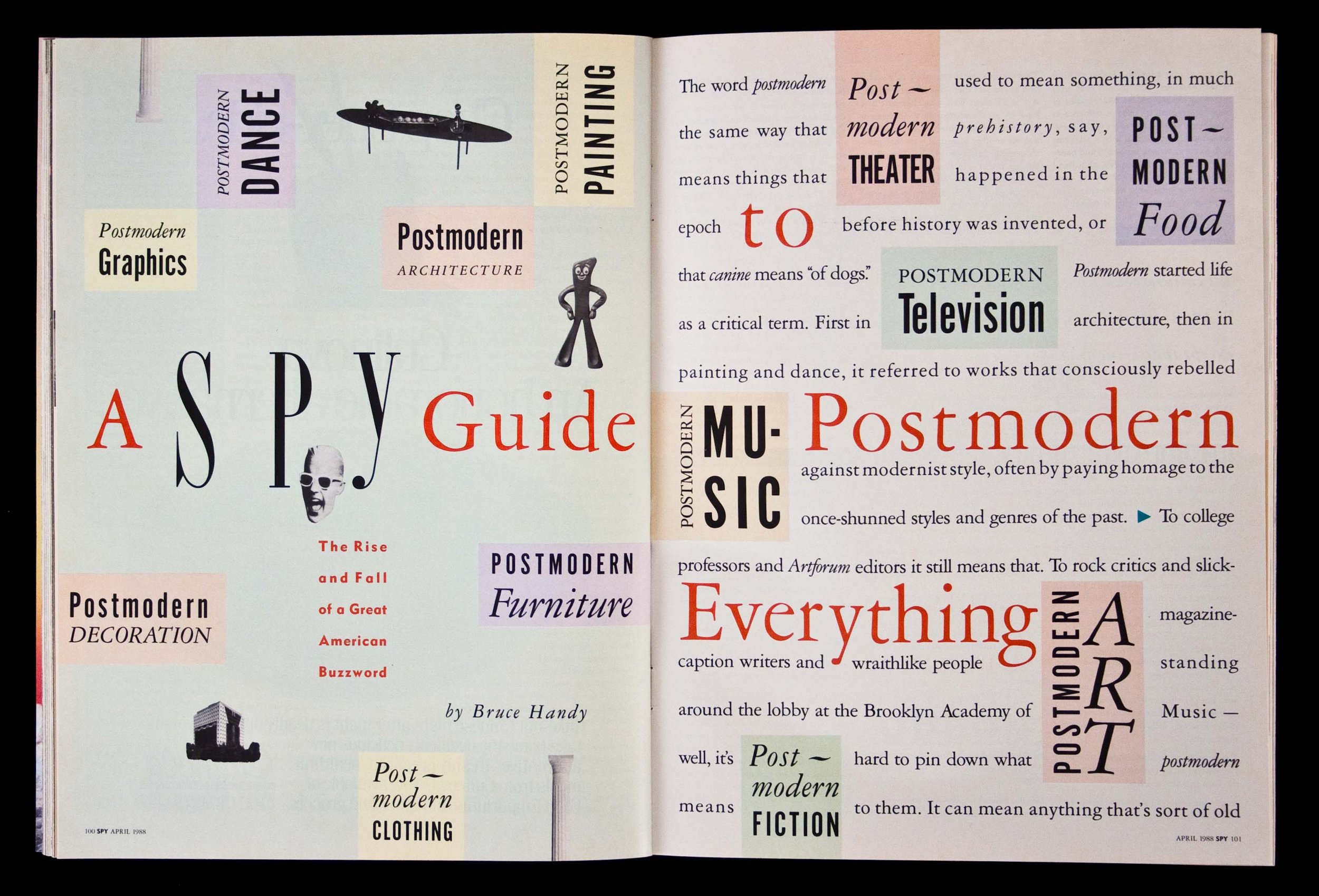

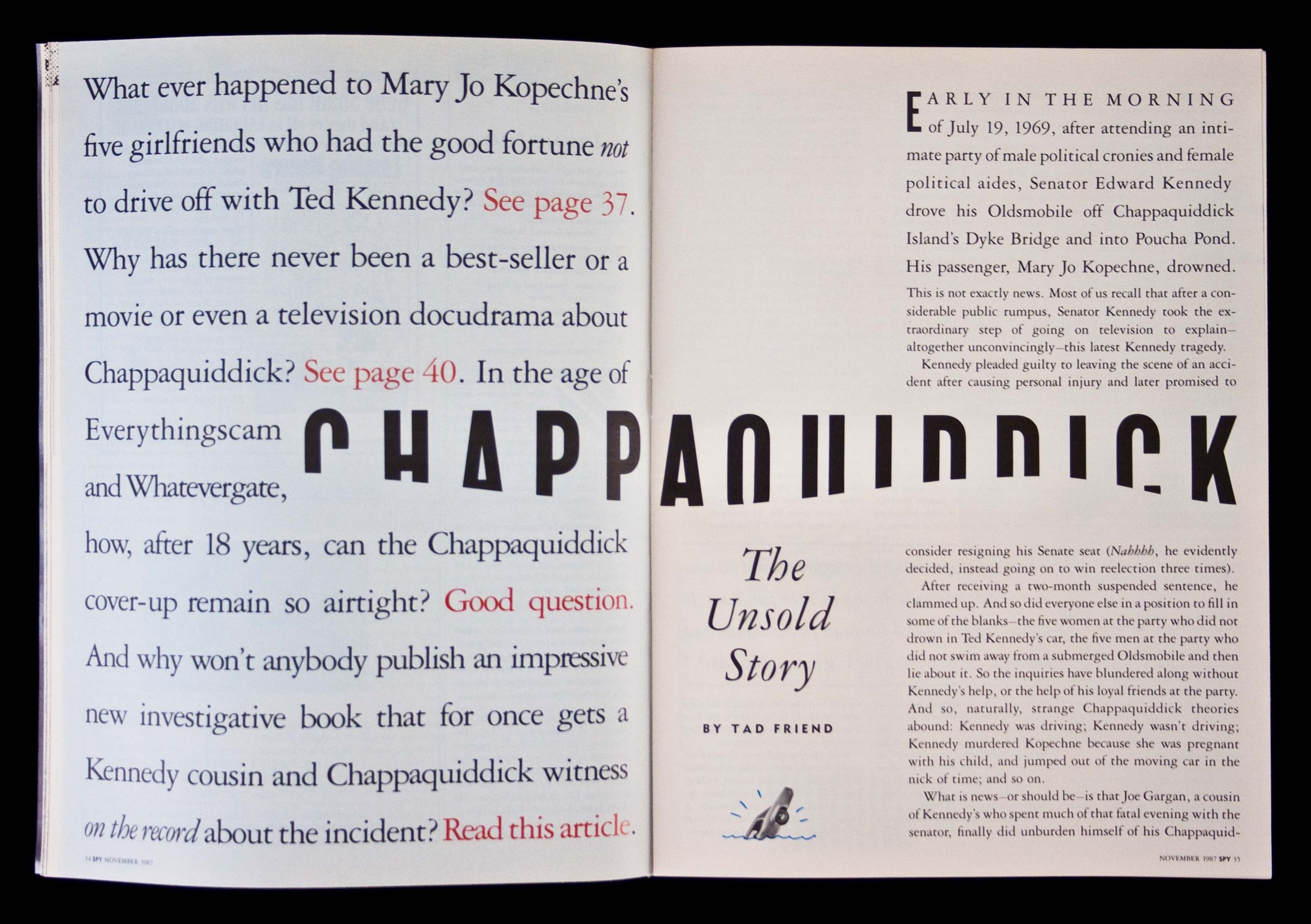

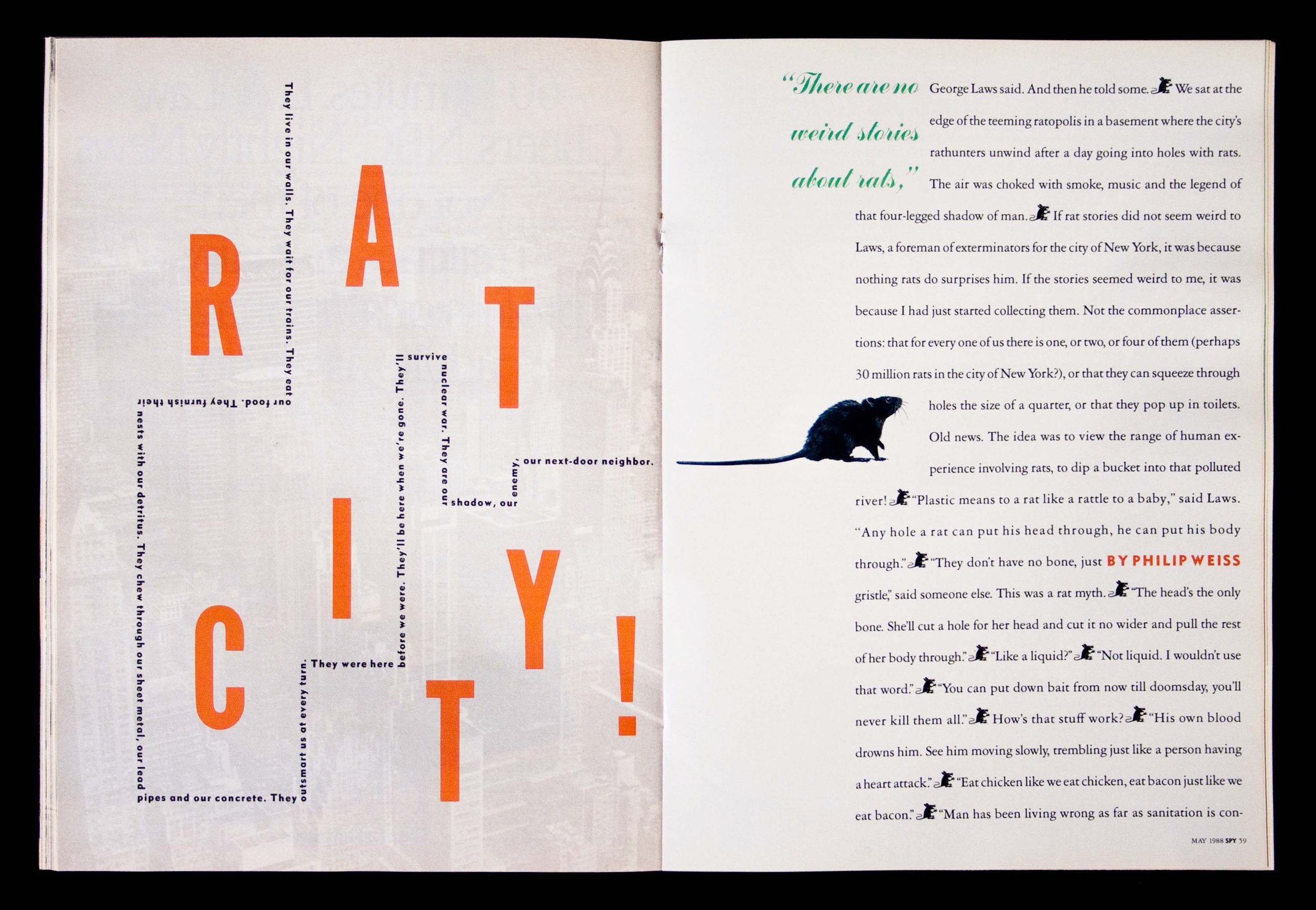

So that’s kind of the competition in the women’s space. And computers were just beginning. So a lot of the interesting magazines were using crazy typography, which I don’t really know how to do. I’m not a typographer.

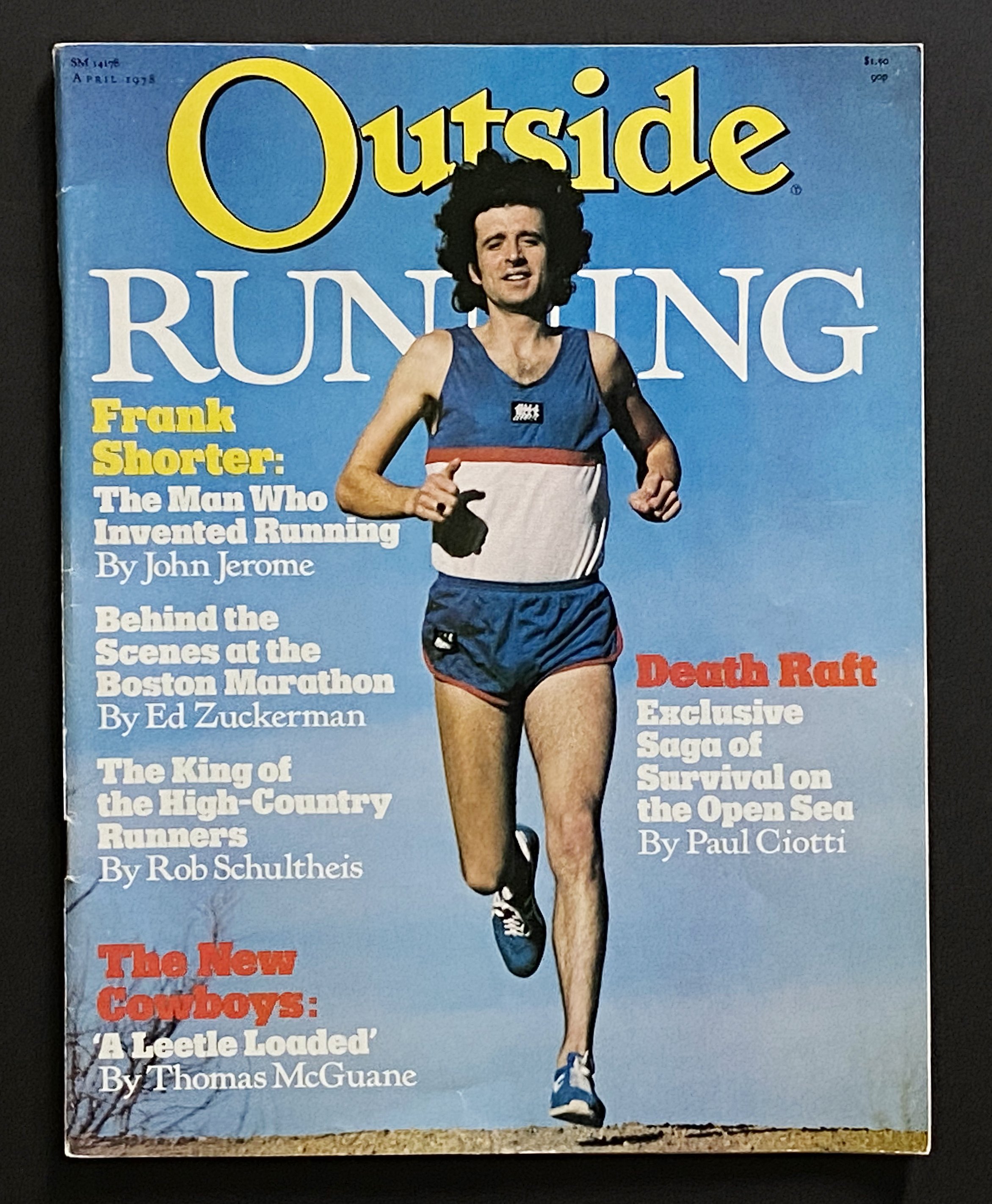

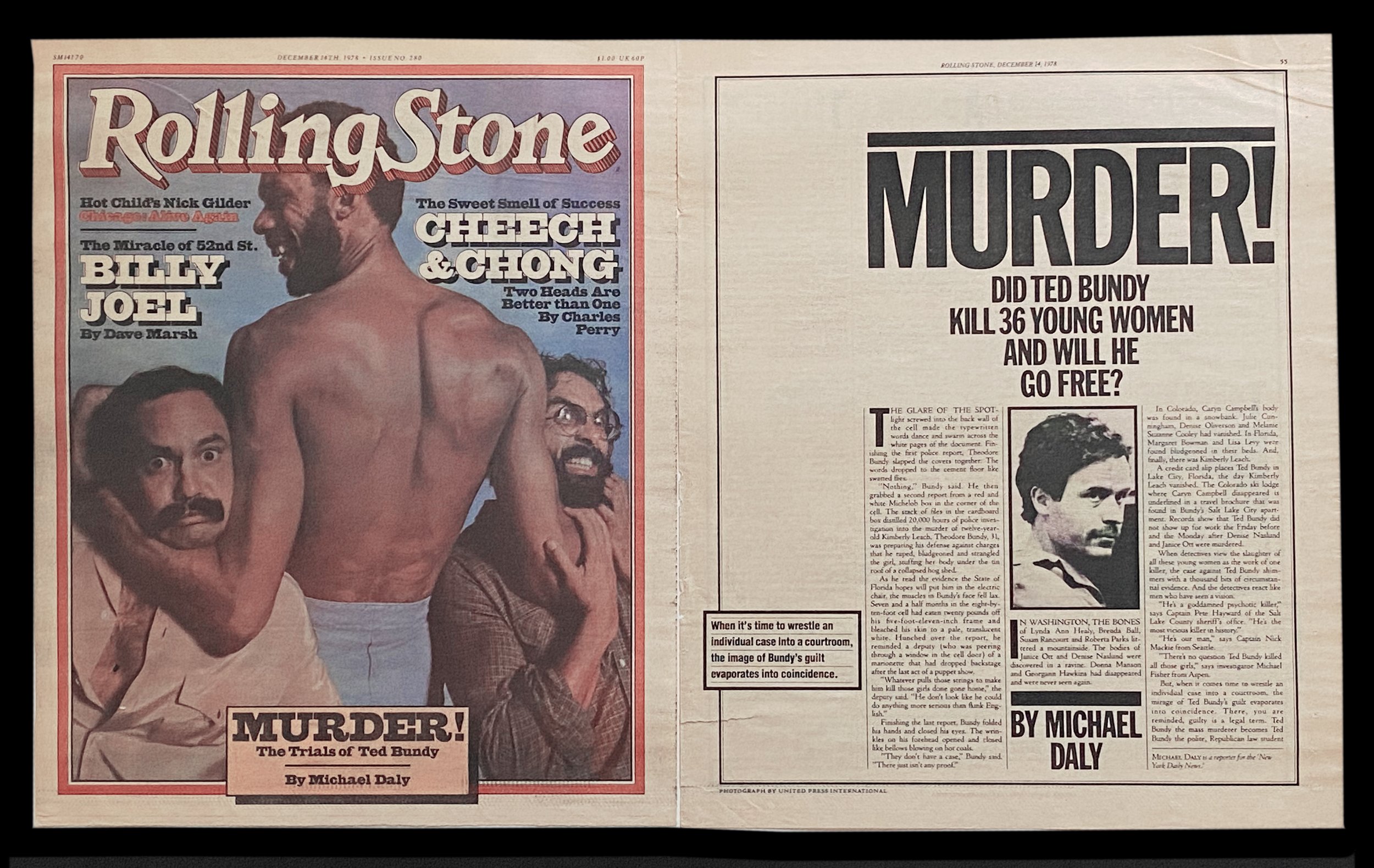

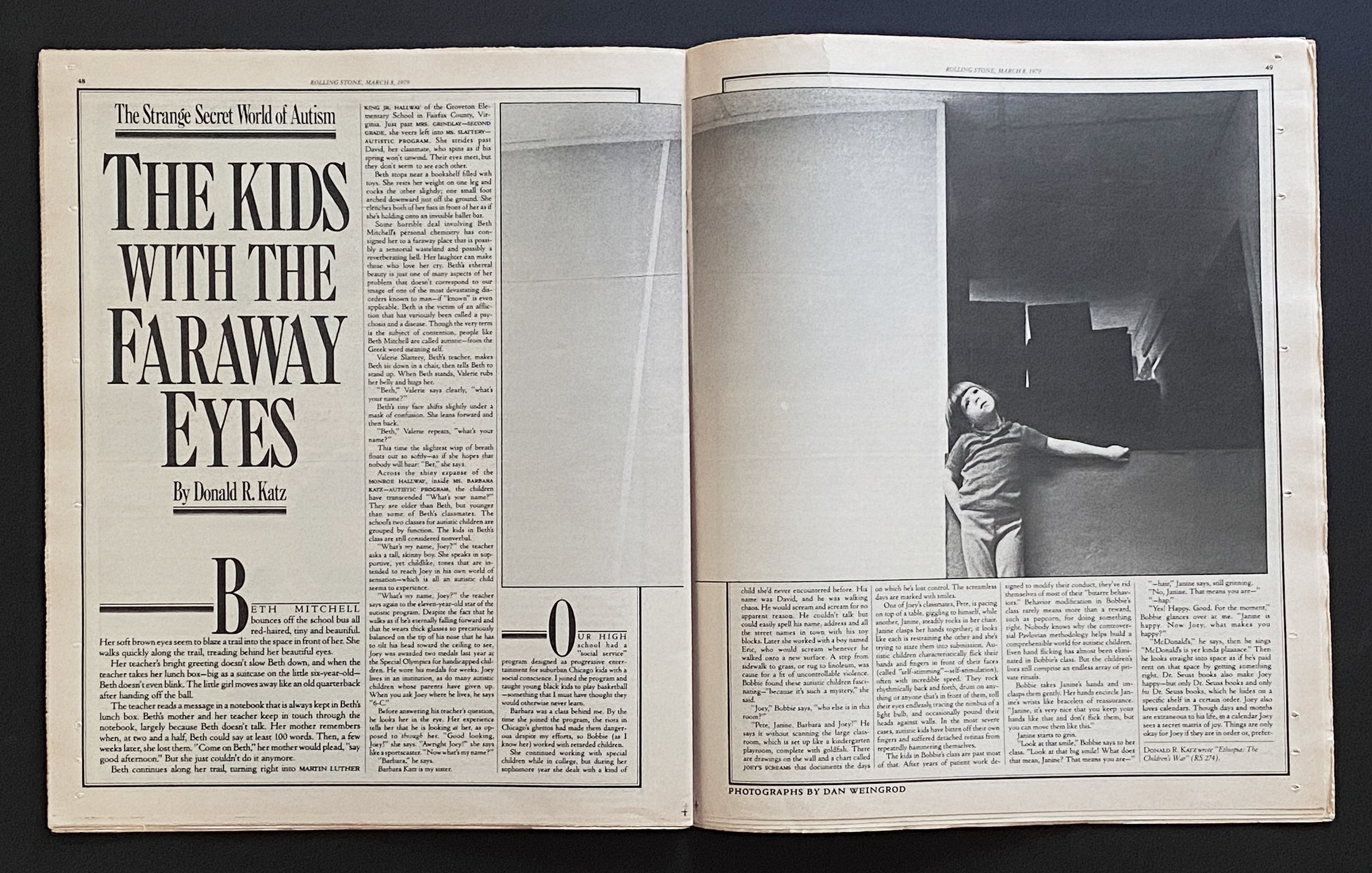

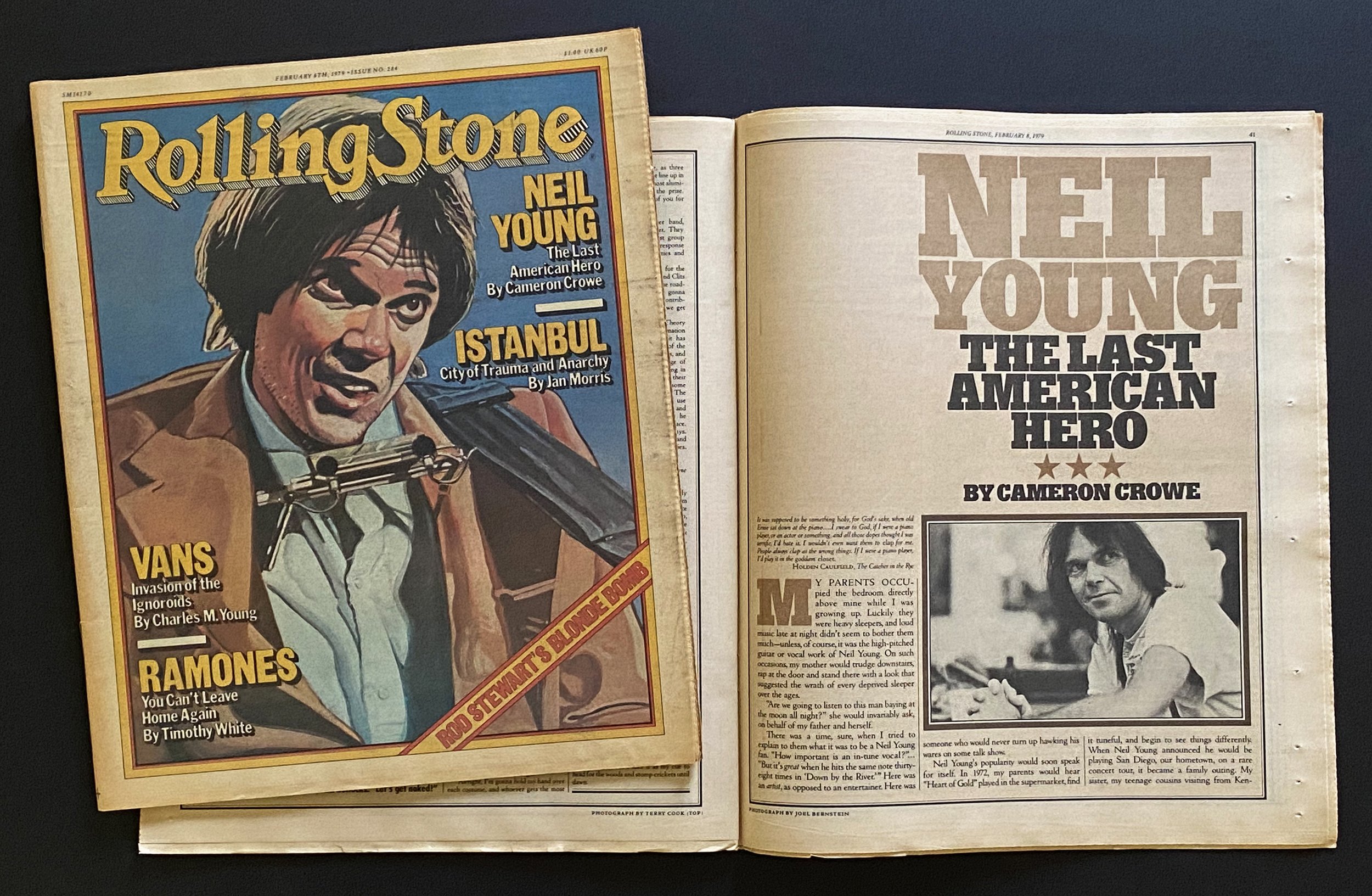

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, this was a few years before Wired. I would guess Fred [Woodward] was at Rolling Stone at the time.

Gael Towey: Right.

Patrick Mitchell: But not much else was going on, generally, in the magazine business design-wise?

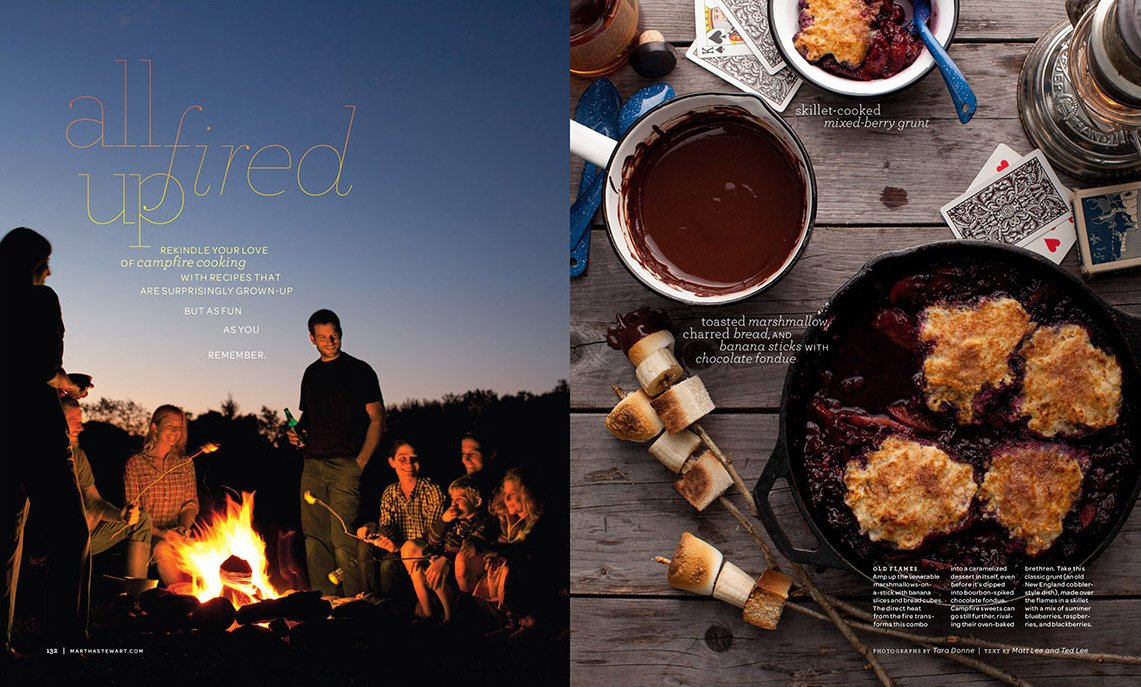

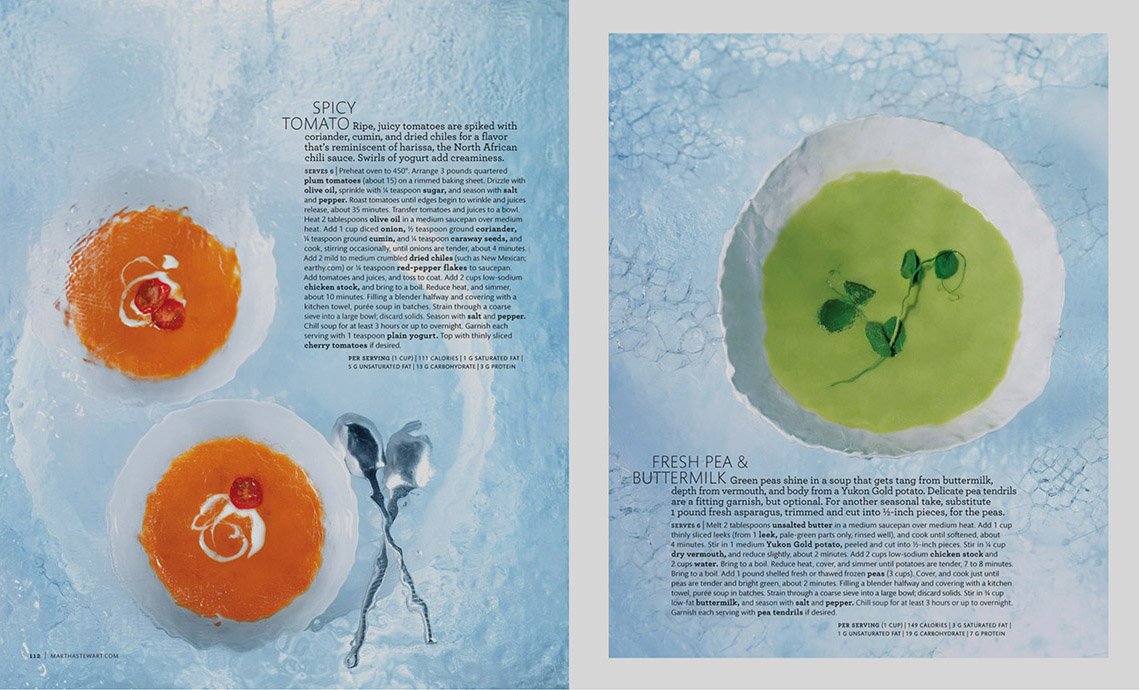

Gael Towey: No. And that kind of computer crazy typography scared me, you know. I really didn’t know how to do it. So, since Martha and I really wanted the new magazine to be very photography-based, we elected to do quite simple typography.

Debra Bishop: Martha Stewart Living was truly revolutionary when it launched. Before Martha, shelter content was often very traditional and stuffy—do you remember Victoria magazine?

Gael Towey: Yes. Yes.

Debra Bishop: What made the Martha Stewart Living approach so unique?

Gael Towey: Can I tell my photography story about getting canceled by Condé Nast?

Debra Bishop: Oh, sure.

Gael Towey: When we started the magazine, we did it so fast! Isolde Motley, who was our first editor in chief, and I met at Clarkson Potter. We both worked with Martha at Clarkson Potter, so the three of us were a kind of known entity to one another. We had all worked together before. So it wasn’t, like, completely nutty.

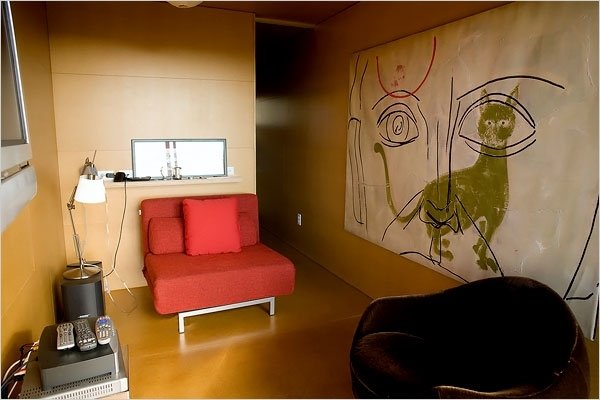

We started working on August 1st, 1990, and we had the first issue, which was a test issue, on the newsstand November 12th, 1990, which is an unbelievably fast trajectory in terms of doing a magazine. I had met all these wonderful photographers when I was art director of House & Garden.

And as soon as I started working at Martha Stewart, I called them and asked them to work for us and do stories for us. And they all kept saying “no.” And finally one of them said to me, “You know, Gael, you’ve been embargoed. None of us are allowed to work for you. We can’t work for you or Martha.” And I was petrified.

I thought, “oh my gosh, what am I going to do now?” So we had to find photographers who did not work for magazines. And that changed—so your question was, “ How did you change the look of women’s magazines?” That was part of it. It forced us to go to a different group of people and work in a different way.

And that’s part of what made us so unique.

Debra Bishop: Mm-hmm. It was problem solving.

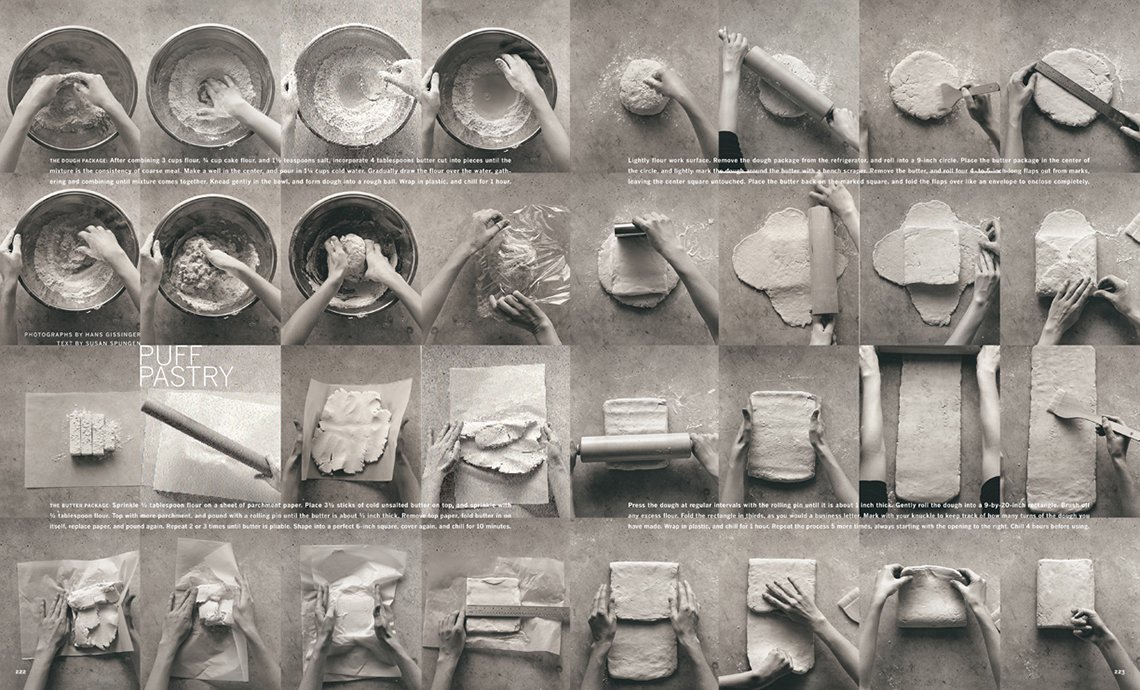

Gael Towey: And also Martha wanted to do this “how to” magazine. And that meant that we were doing a lot of stuff ourselves.

“And he said, ‘Gael, it’s because it’s a fashion company. You go into fashion and out of fashion. And that’s just the way it is.’ I thought, ‘Oh my God, how depressing.’”

Debra Bishop: So when you started the magazine, was there a brief for Martha or did everything happen sort of organically as you’re describing?

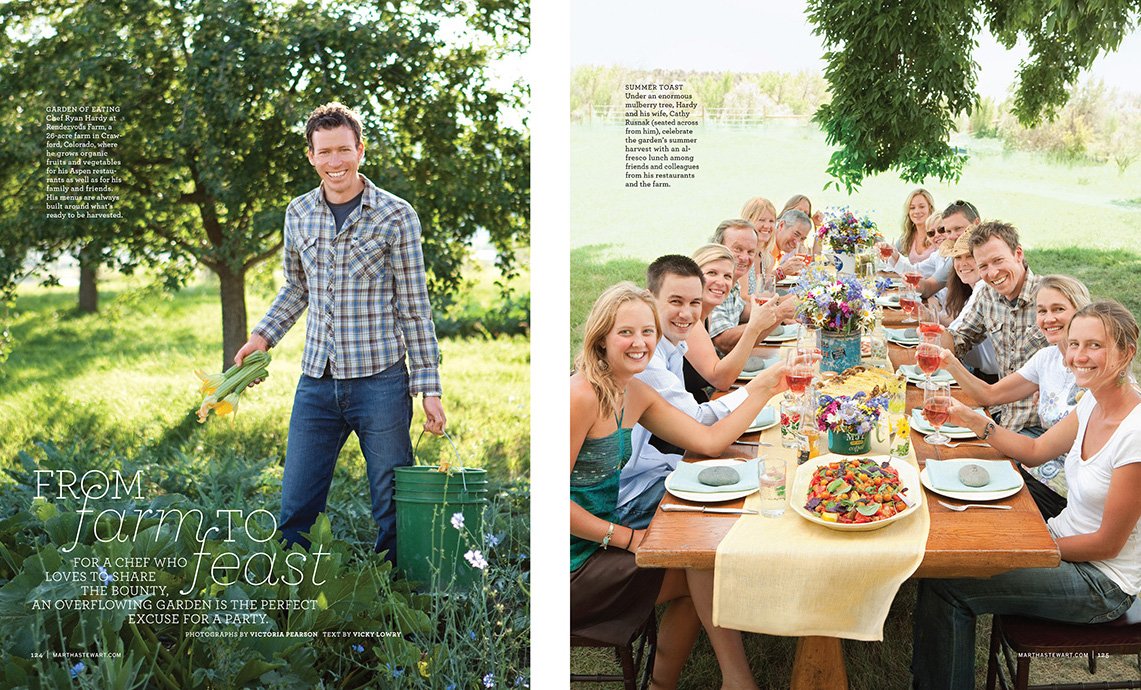

Gael Towey: The brief was “inspiration and information.” There were things that she liked. It was kind of an amalgamation of all the things that she liked to do, really, and that she was quite good at. She had amazing gardens in Westport. She was a wonderful chef and cook. So those are all the things that obviously really interested her.

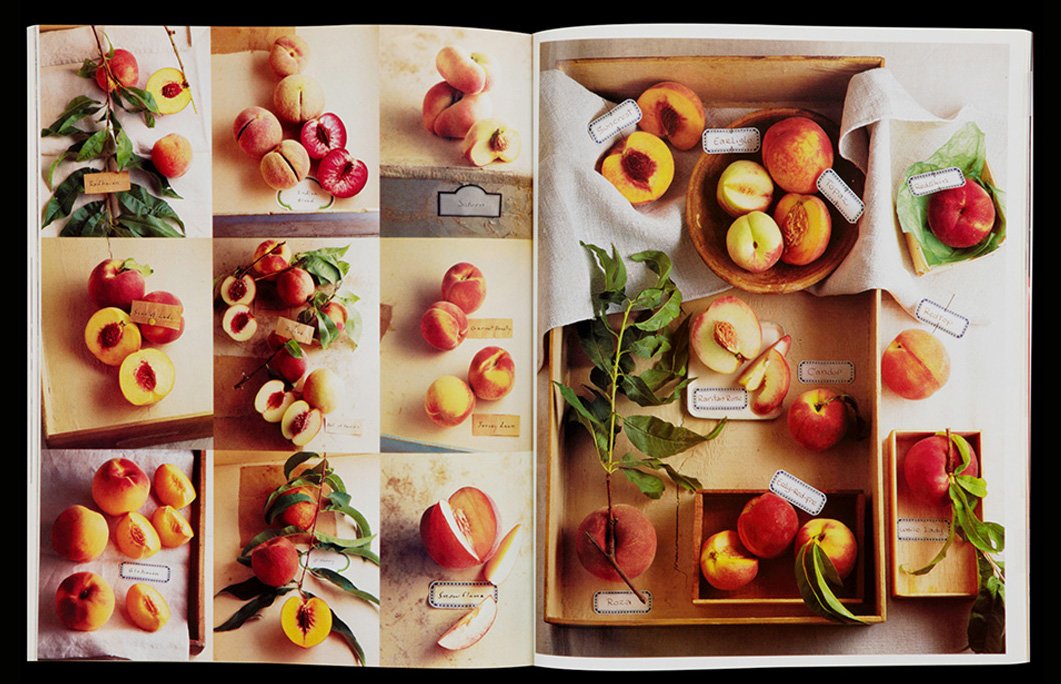

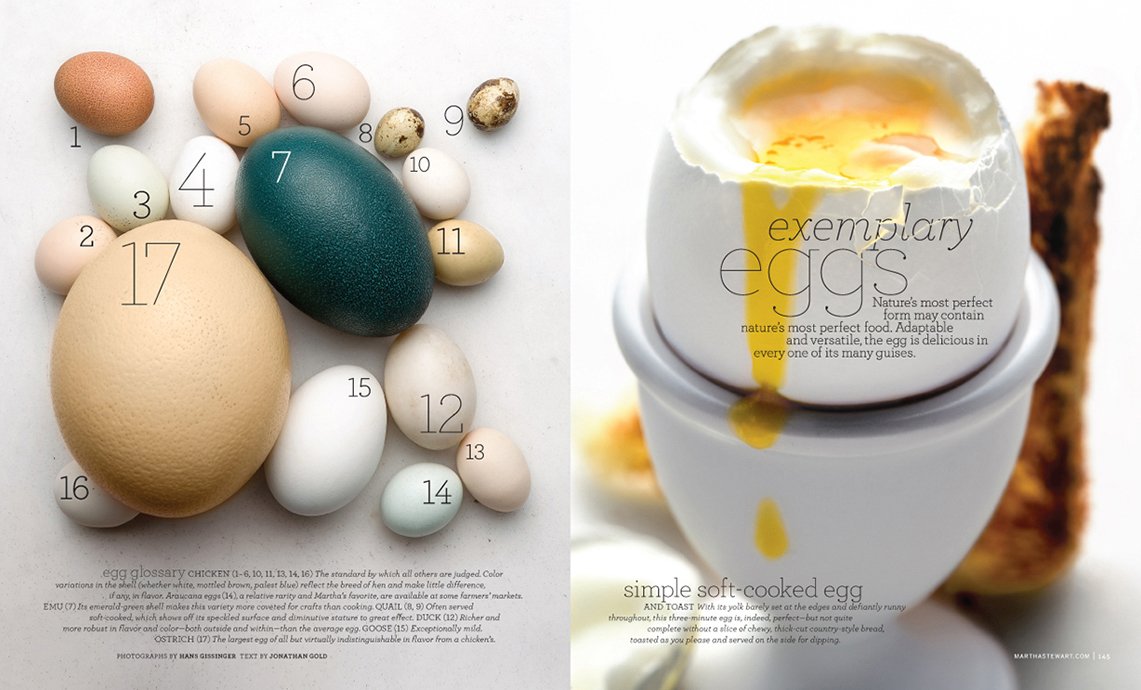

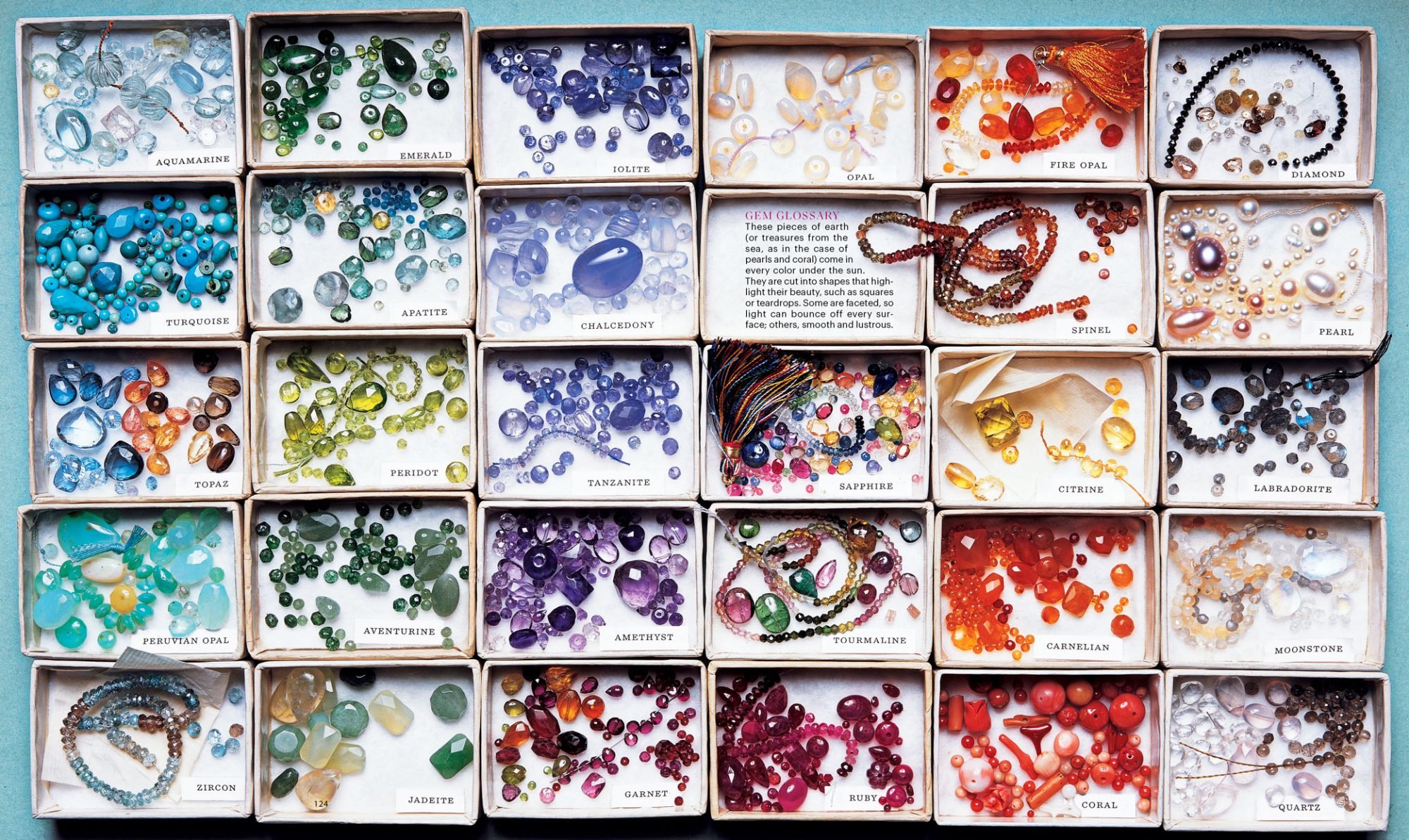

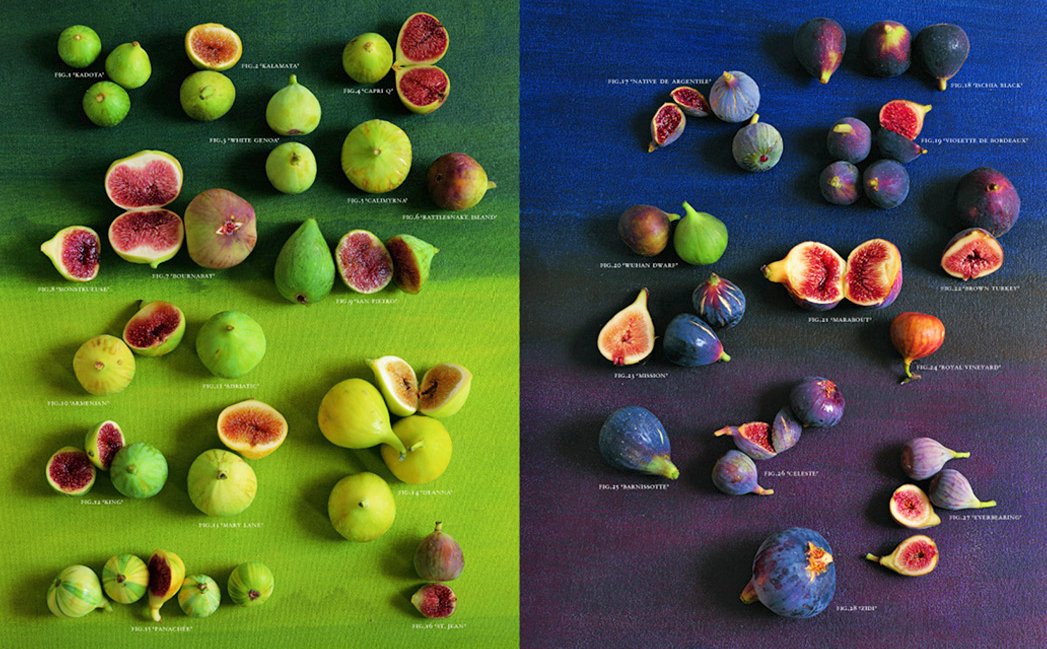

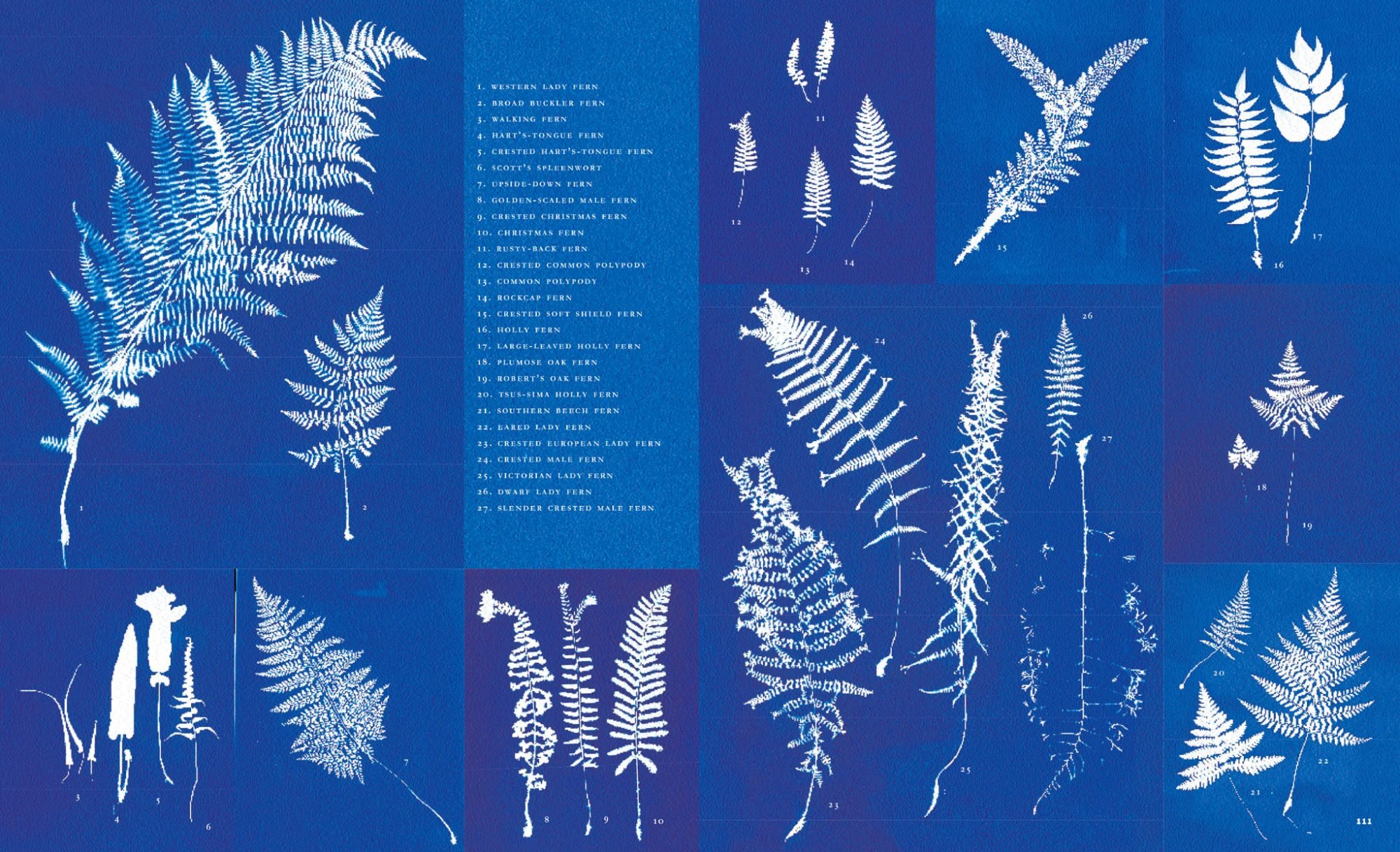

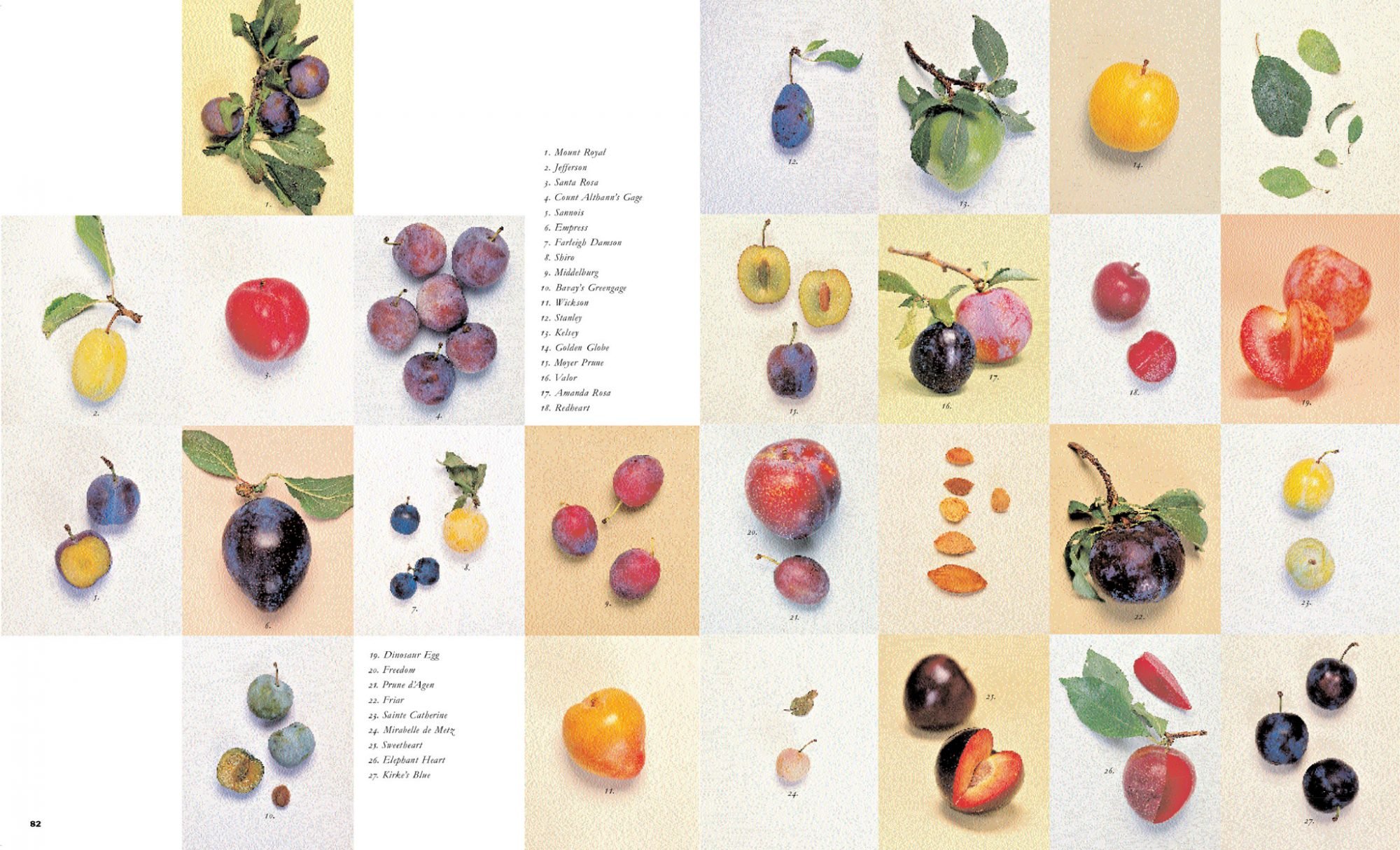

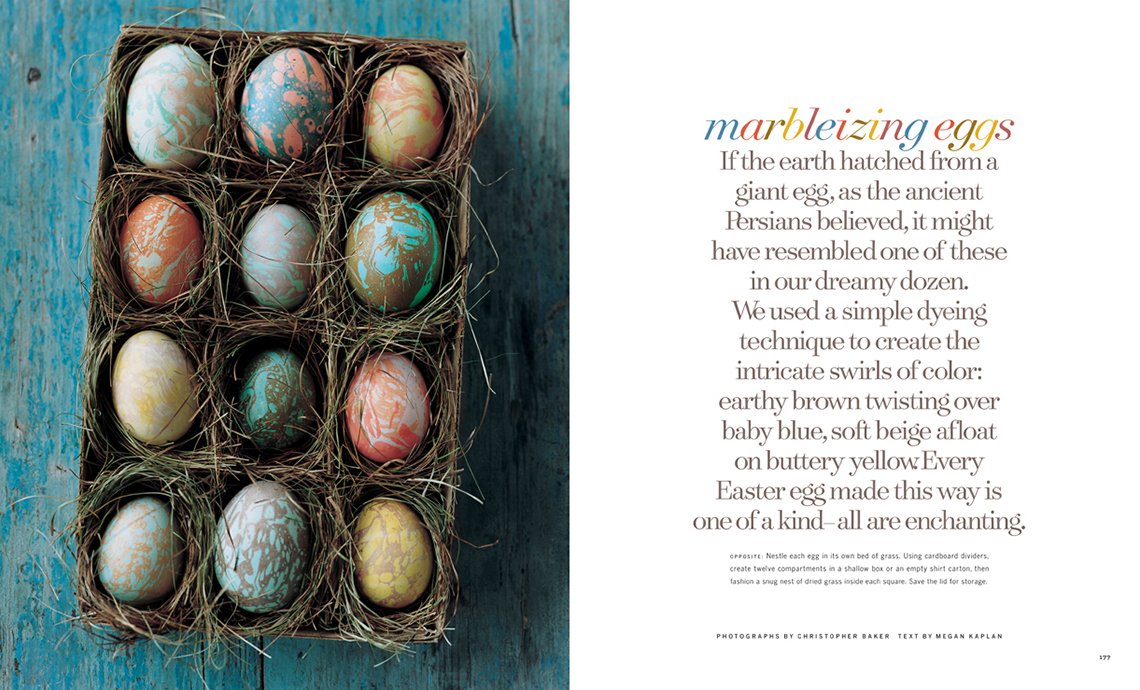

She had these Eyewitness books by Dorling-Kindersley, which talk about things like trees or apples or something like that in incredible detail. And she was a very detail-oriented person and she brought in these books and she said, “I’d like the magazine to be like this.”

And they were drawings of every single kind of deciduous tree with lots of information about them. And that’s what we turned into our, kind of, famous glossaries. And that became a real opportunity for experimentation. And what Claudia Bruno calls the “creative laboratory.”

Debra Bishop: From the beginning, the magazine was influential for its modernity and simplicity of design. I always remember the minimalistic typography, all lower case headlines, which nobody else in the business could do. People tried to emulate it. But editors wouldn’t allow it anywhere else. So it was actually kind of irreverent and modern.

What were the other hallmarks that defined the brand? What about the photography? I think it was revolutionary for its time.

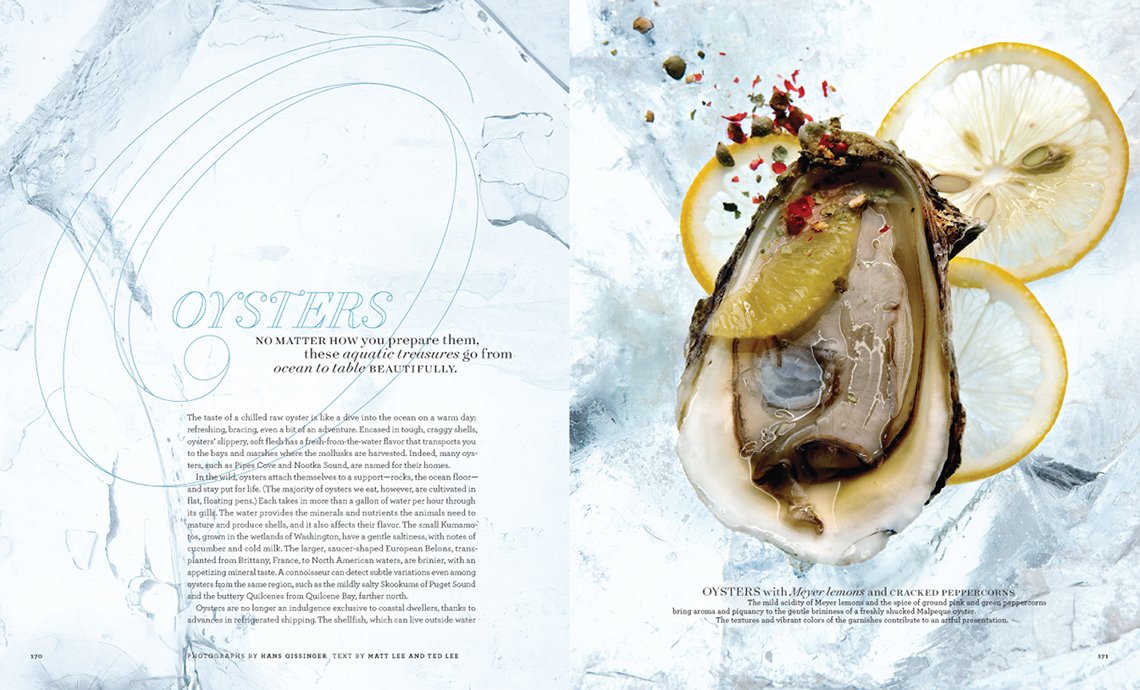

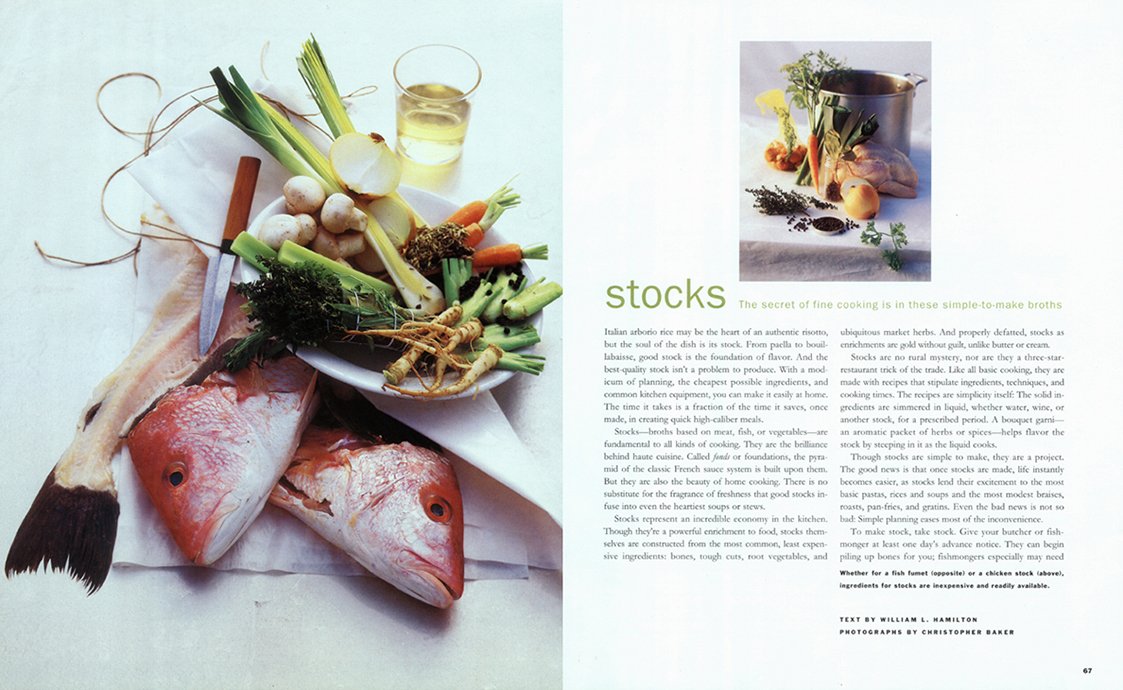

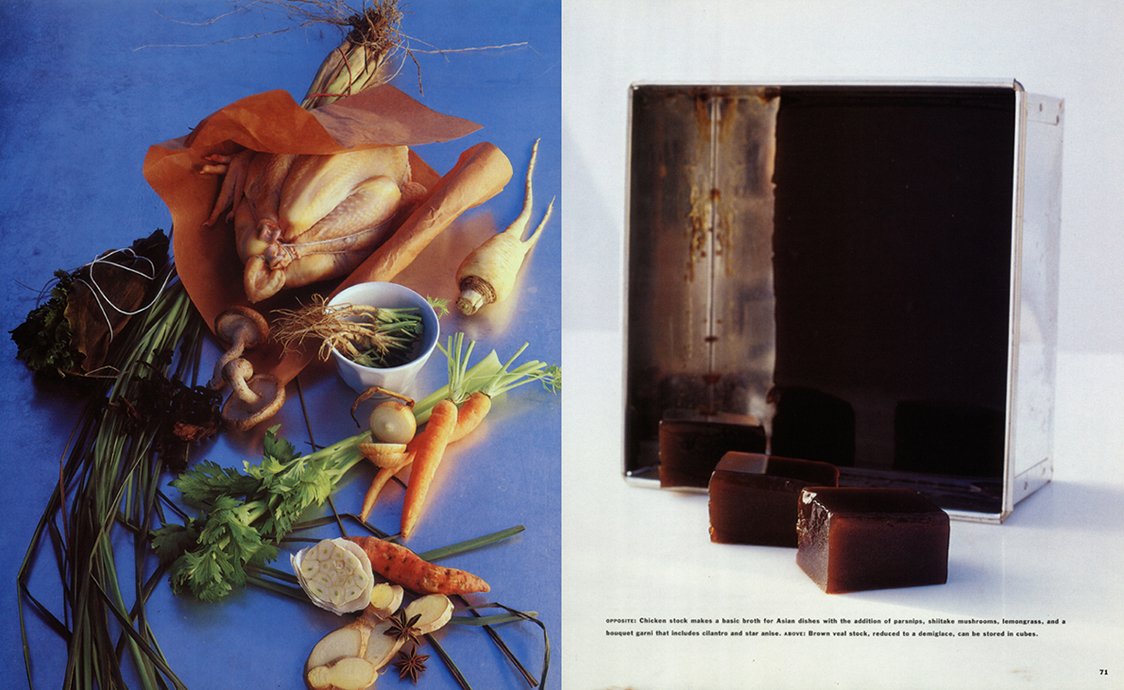

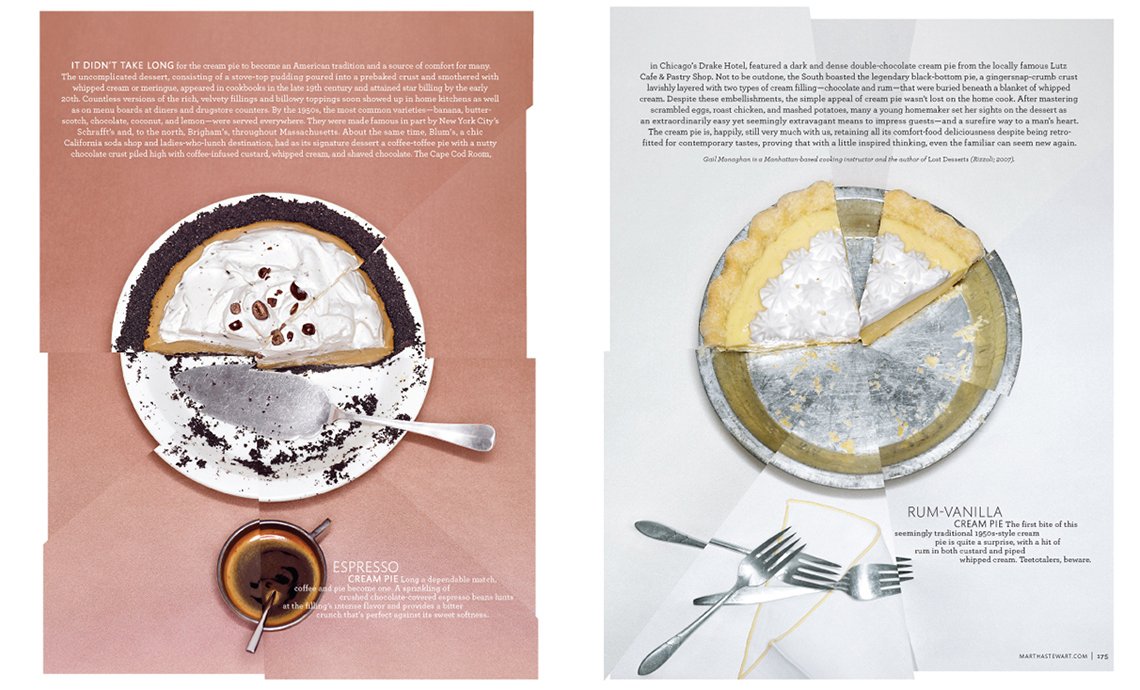

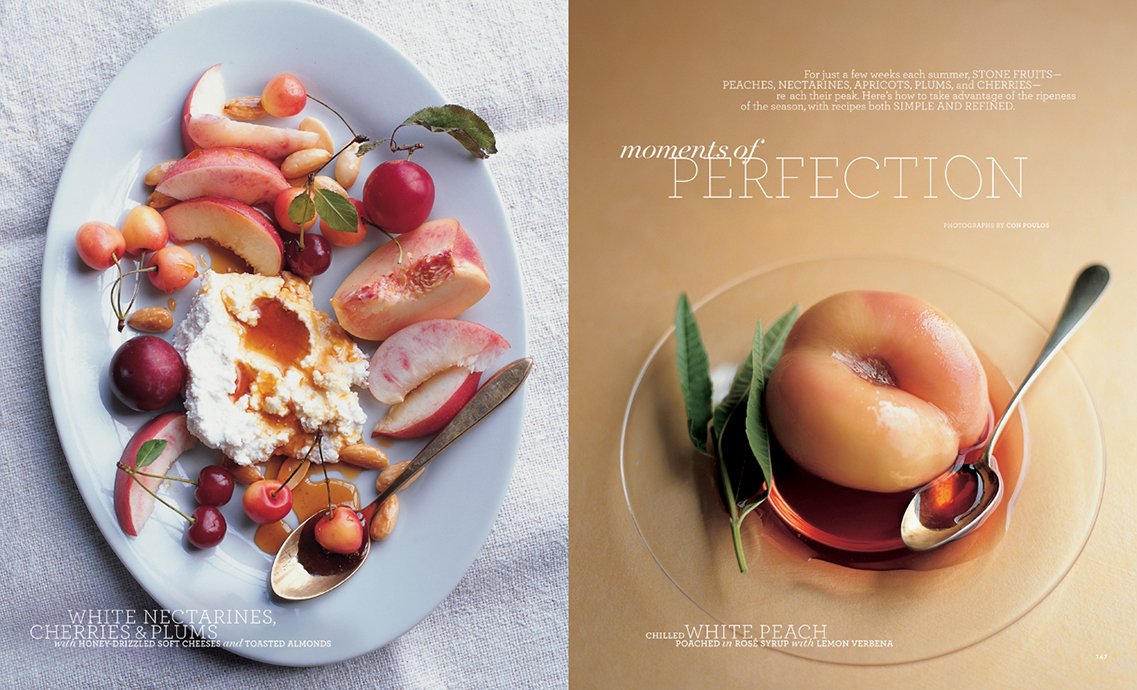

Gael Towey: I think the photography was very natural and that came out of what became brand values, actually, that Martha started from the way she did her books.

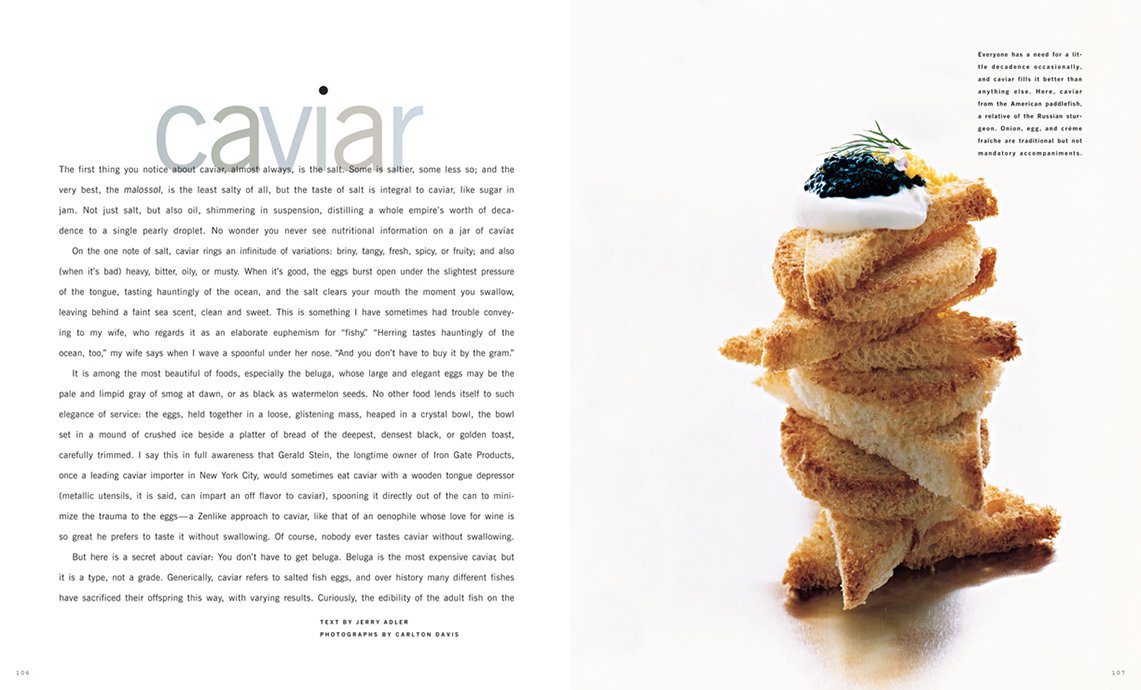

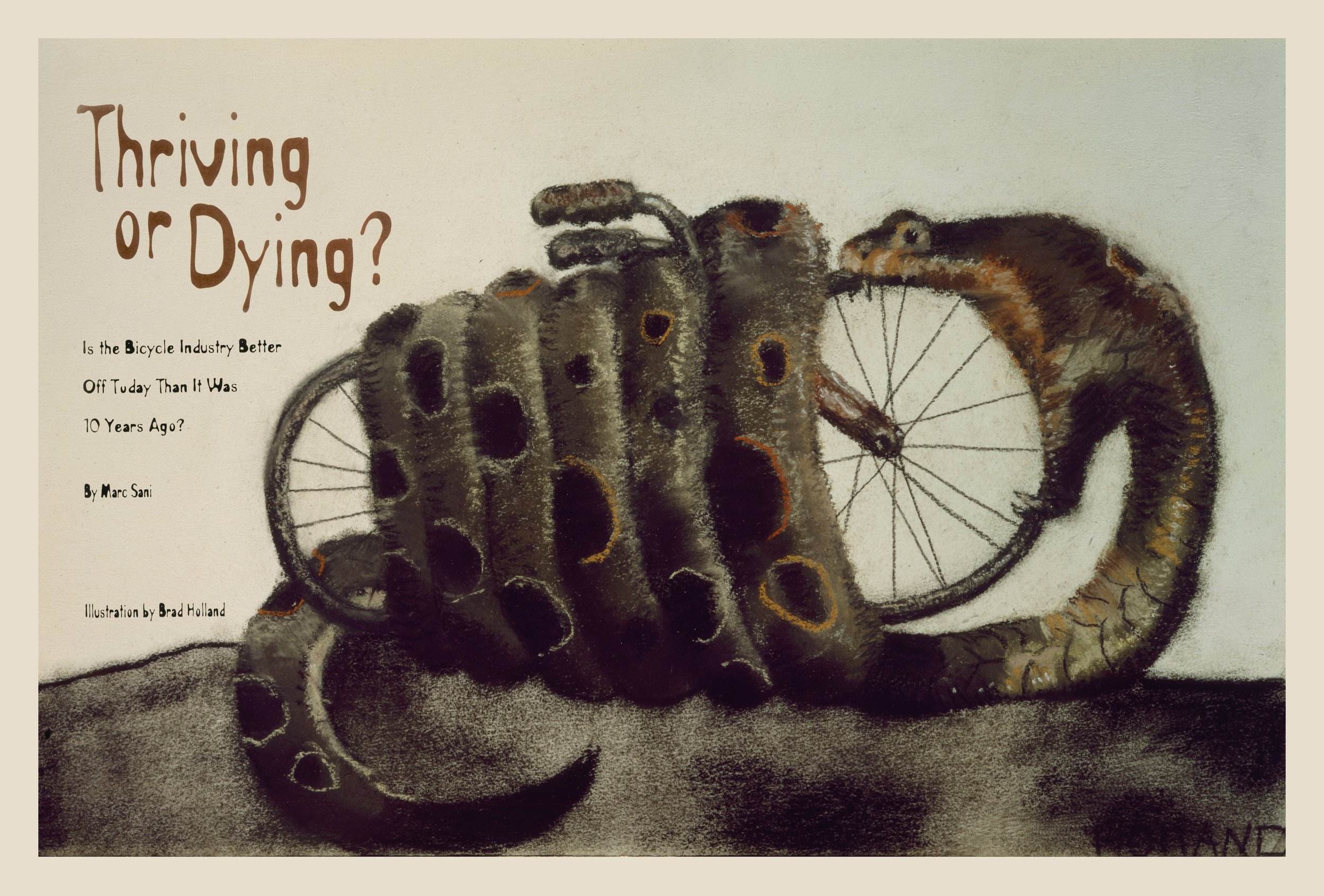

And when we did food, you were not allowed to use any fakery at all. And the person who developed the recipe would also be the person who created the recipe for the camera. So you had to create a recipe that worked and that looked really good. And then, of course, somebody else did the testing.

But that forced the recipe developers, the food editors, to create a recipe that also looked good for the camera. And that’s very unusual, because still, to this day, a lot of cooking magazines, and newspapers, and so forth, they’ll take a recipe and then they’ll hire a stylist to actually cook it.

And so it’s a separate thing. Whereas in our situation it was all by the same person. And they were really artists. People like Susan Spungen, who was a painting major in college. She looked at food almost as an art form.

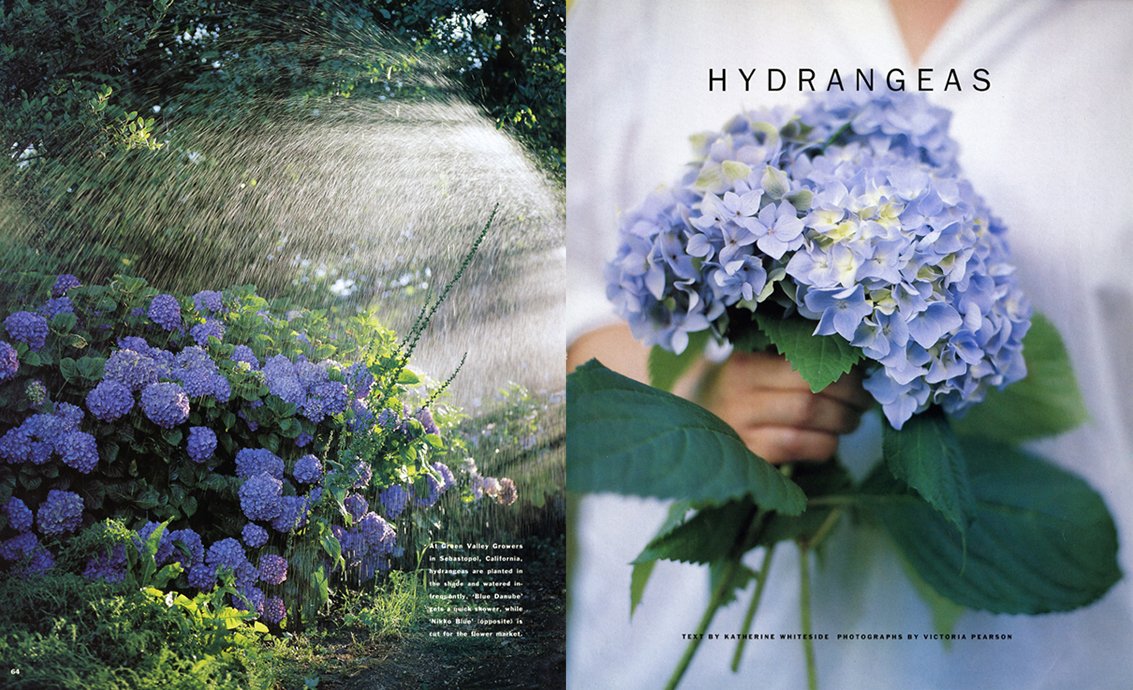

Debra Bishop: And the photography style was very natural and beautiful. A lot of natural light. There were certain people who brought beautiful style and a way of showcasing the food, or flowers, or whatever it was, and it became an iconic style within the magazine. Talk a little bit about the early photo shoots.

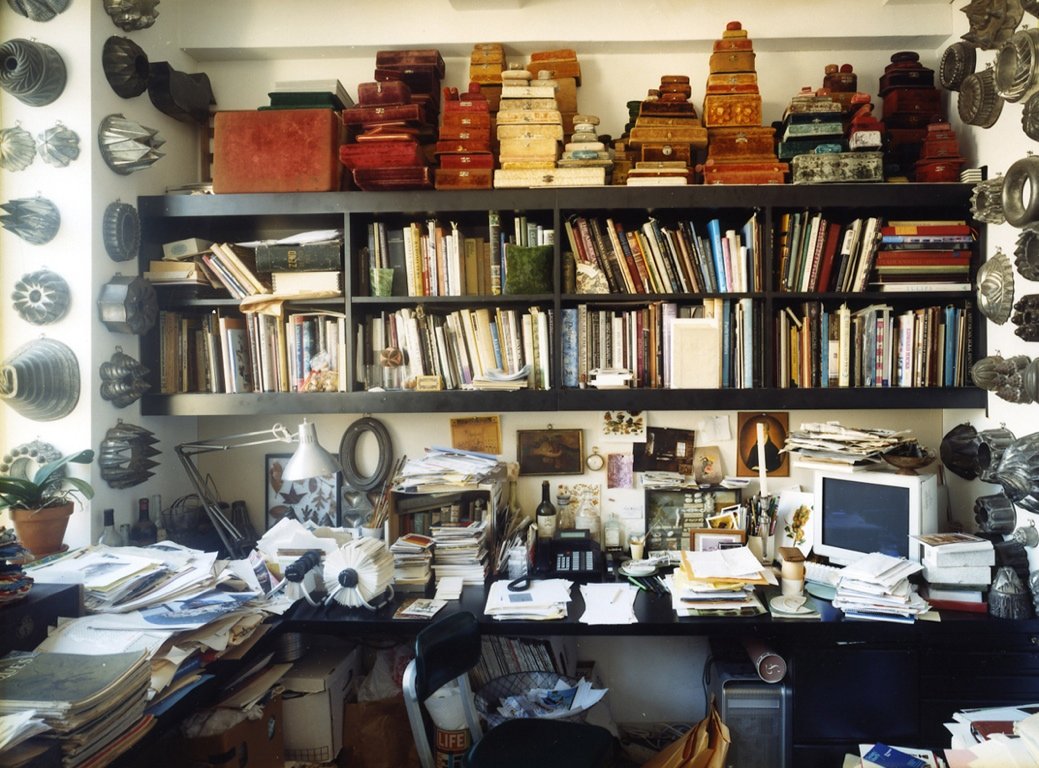

Gael Towey: I was very proud of the fact that when you looked down the row of designers sitting at their computers, they would have a stack of art books next to their computer because they were in charge of researching a concept for how to shoot the story.

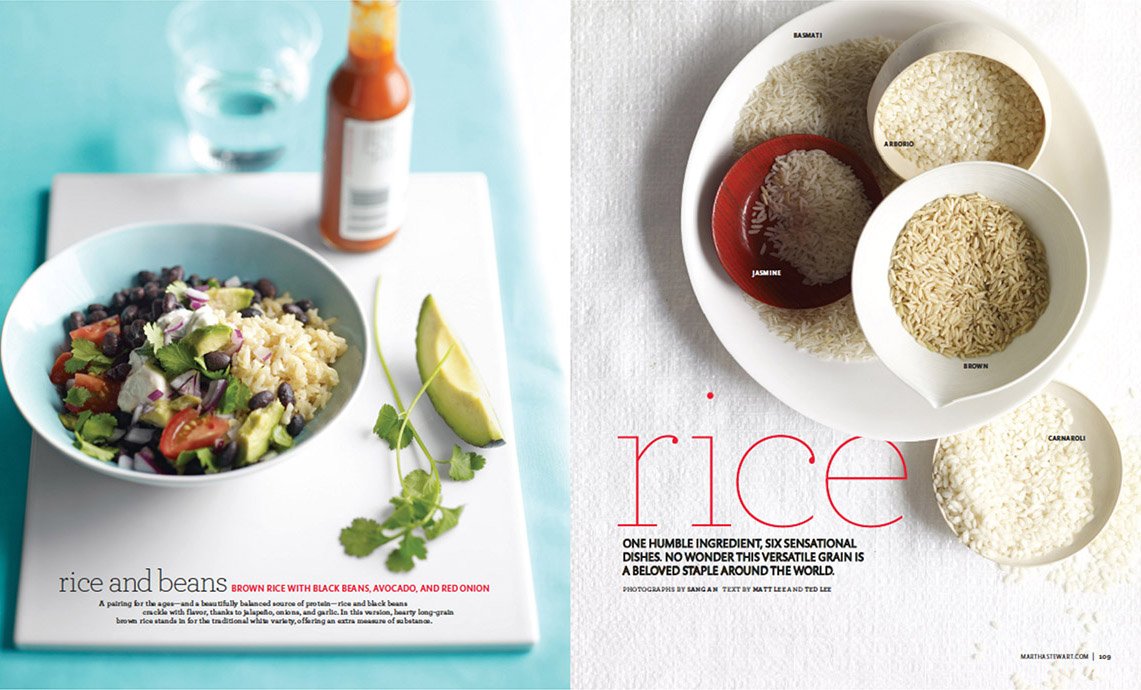

And you have to realize, you know, with women’s magazines, it’s kind of the same old story over and over again. This isn’t the first time that you’ve done a story about rice. Or cakes. Or whatever. And so you had to figure out a way of photographing them that stood out. And photographers like Victor Schrager or John Dugdale who would use 8x10 cameras and create these sort of very beautiful old-world looking still life.

Irving Penn was a big inspiration for us. He was always on the wall of the stylists’ offices. And those photographers who used these kinds of more old-fashioned ways of photographing—Maria Robledo was another person who used the 4x5. They really controlled the light, as you say that it was natural light, and natural light makes things look really “real.”

And the whole idea was to make it real—make it like it would look in your own kitchen, or your own garden, for that matter.

Debra Bishop: And it did.

Gael Towey: The days of photographing gardens were so long you’d have to get there at six o’clock in the morning, and the sun was already coming up, and you’d be there until 10 o’clock at night sometimes.

Debra Bishop: And the light and the naturalness of the photography really gave the magazine an atmosphere.

Gael Towey: Yep. That’s right.

Debra Bishop: I think some photographers, such as Victor for example, who were incredible lighters. But the photography really was so much different, and so much more real, than any other photography that was going on in other magazines at the time.

Gael Towey: Absolutely. Well, thank you. It really was very different from a lot of the magazines at that time, which were very over-lit. And I think natural light made things look appealing and beautiful.

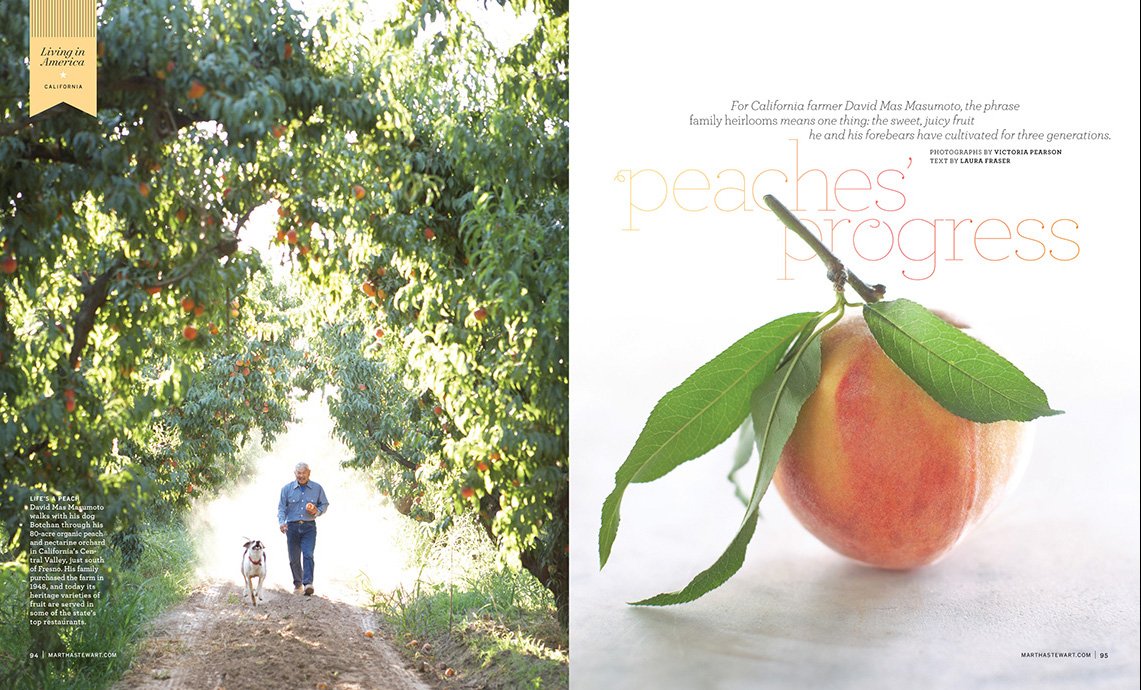

But we also used different photographers. Vickie Pearson was a fashion and portrait photographer. And when I asked her to do still life, she was like, “but I don’t do still life.” And I said, “well, you do. Look at these pictures that you took.” And she was so grateful for us giving her an avenue out of the fashion world.

And it really transformed her. But she made food and still life look like it was a living thing. And the way she photographed, she was always moving. She was engaged with everything in this life happening in front of your eyes.

Patrick Mitchell: I just loved those Martha Stewart glossaries that you talked about: “Seventy-two Breeds of Carrots,” “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Peonies,” etcetera.

Gael Towey: Yeah.

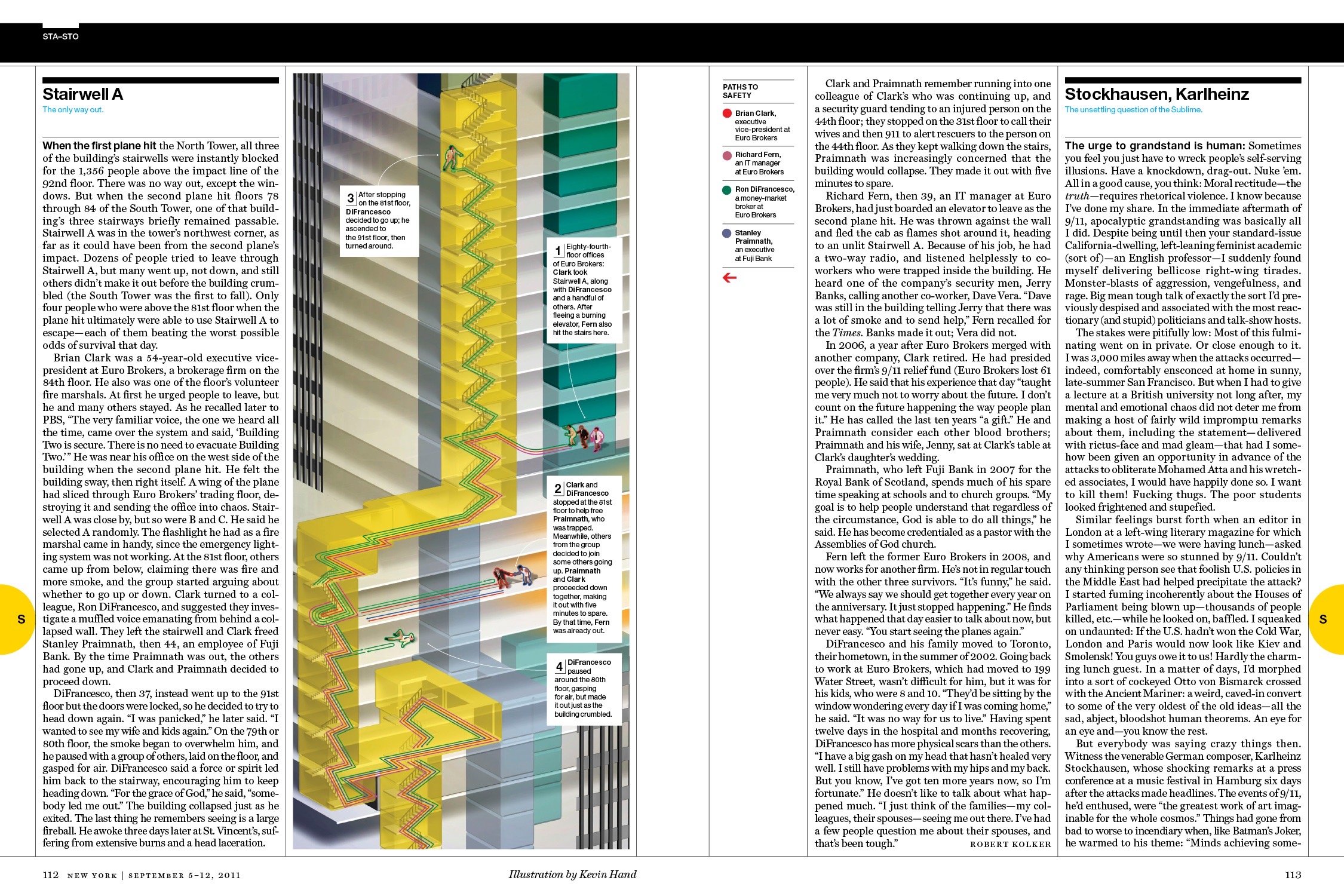

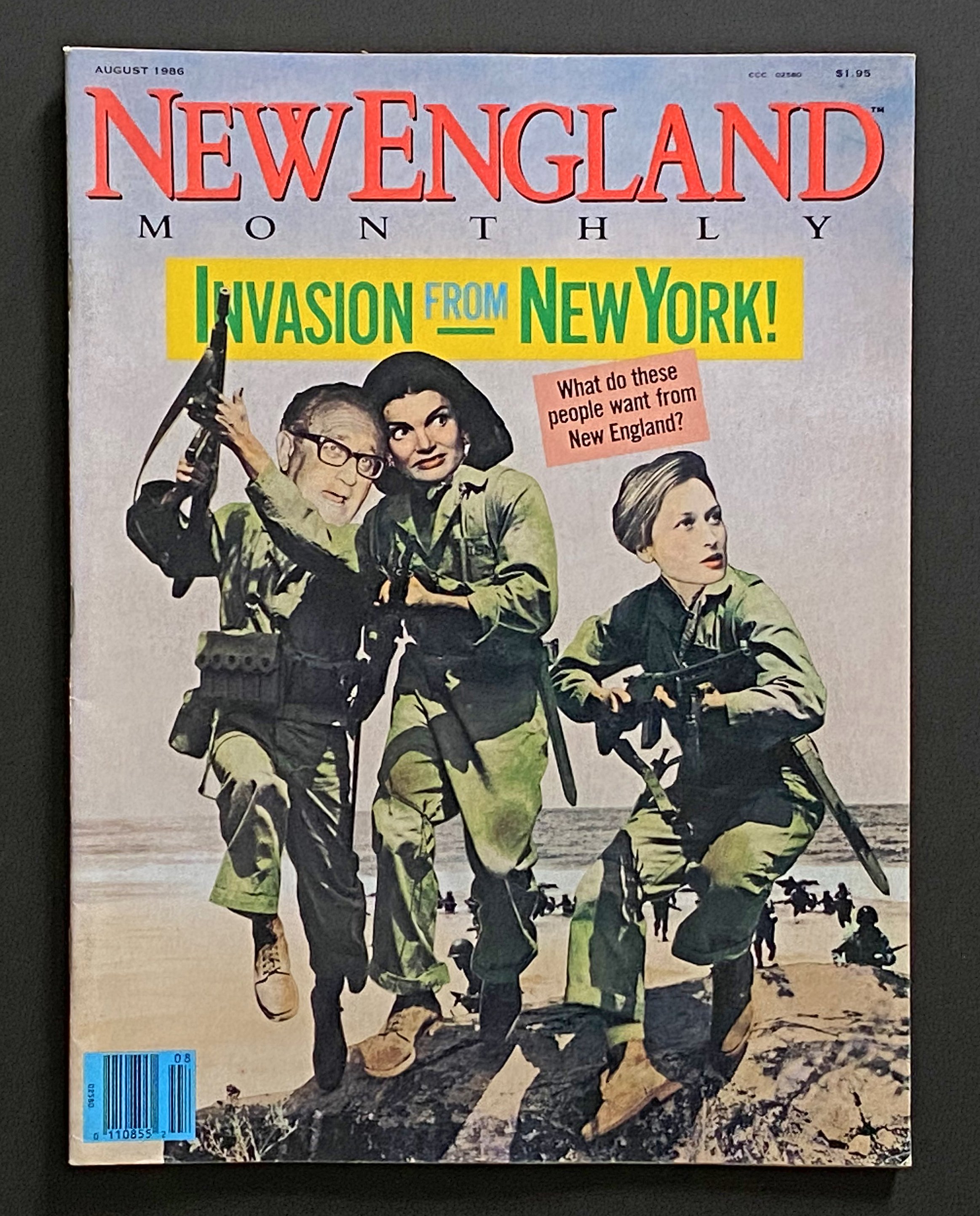

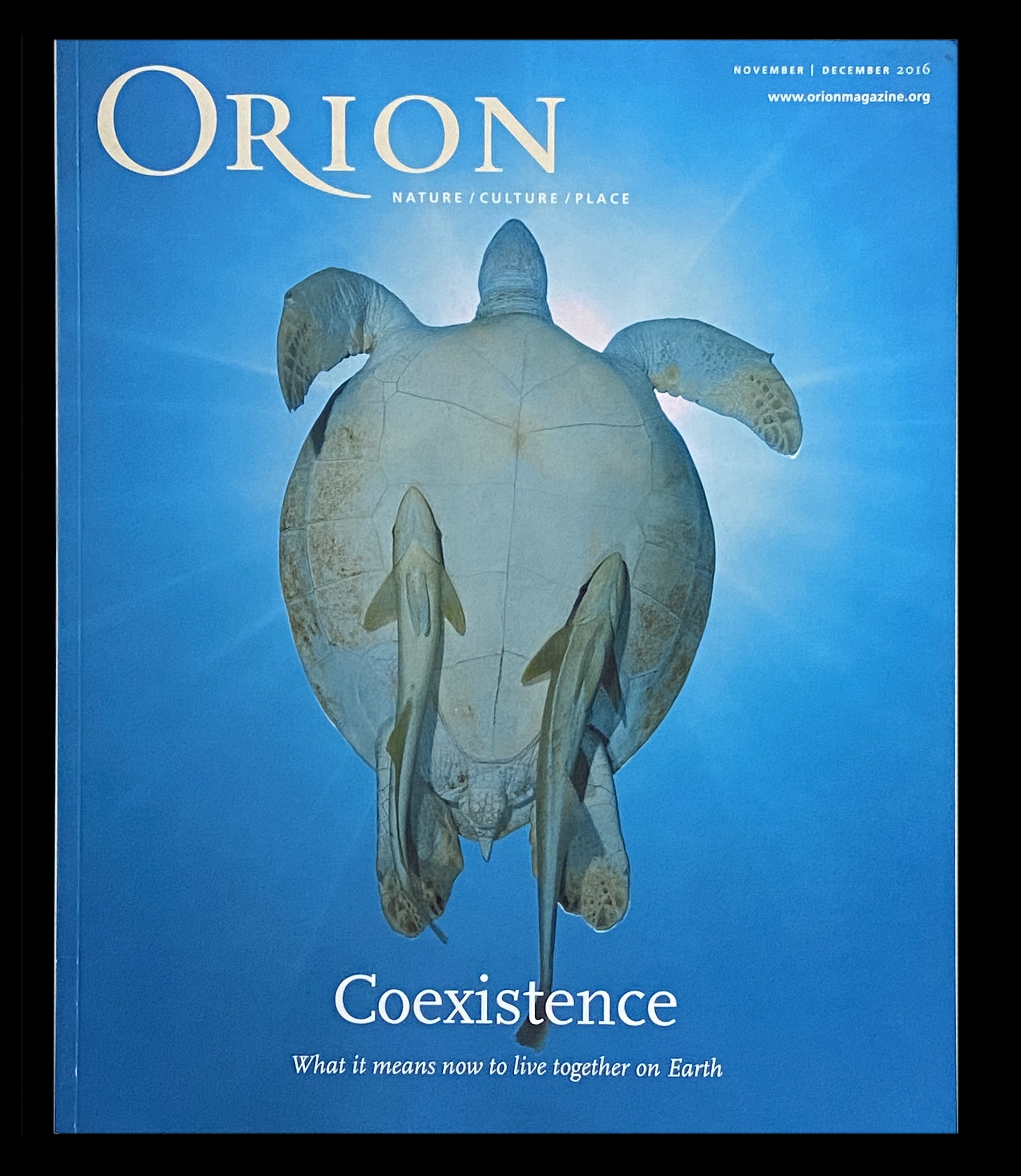

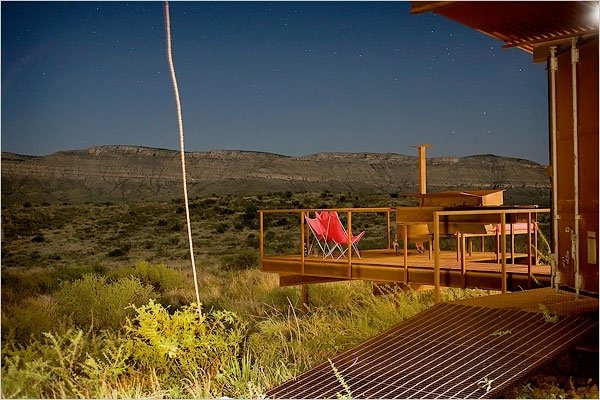

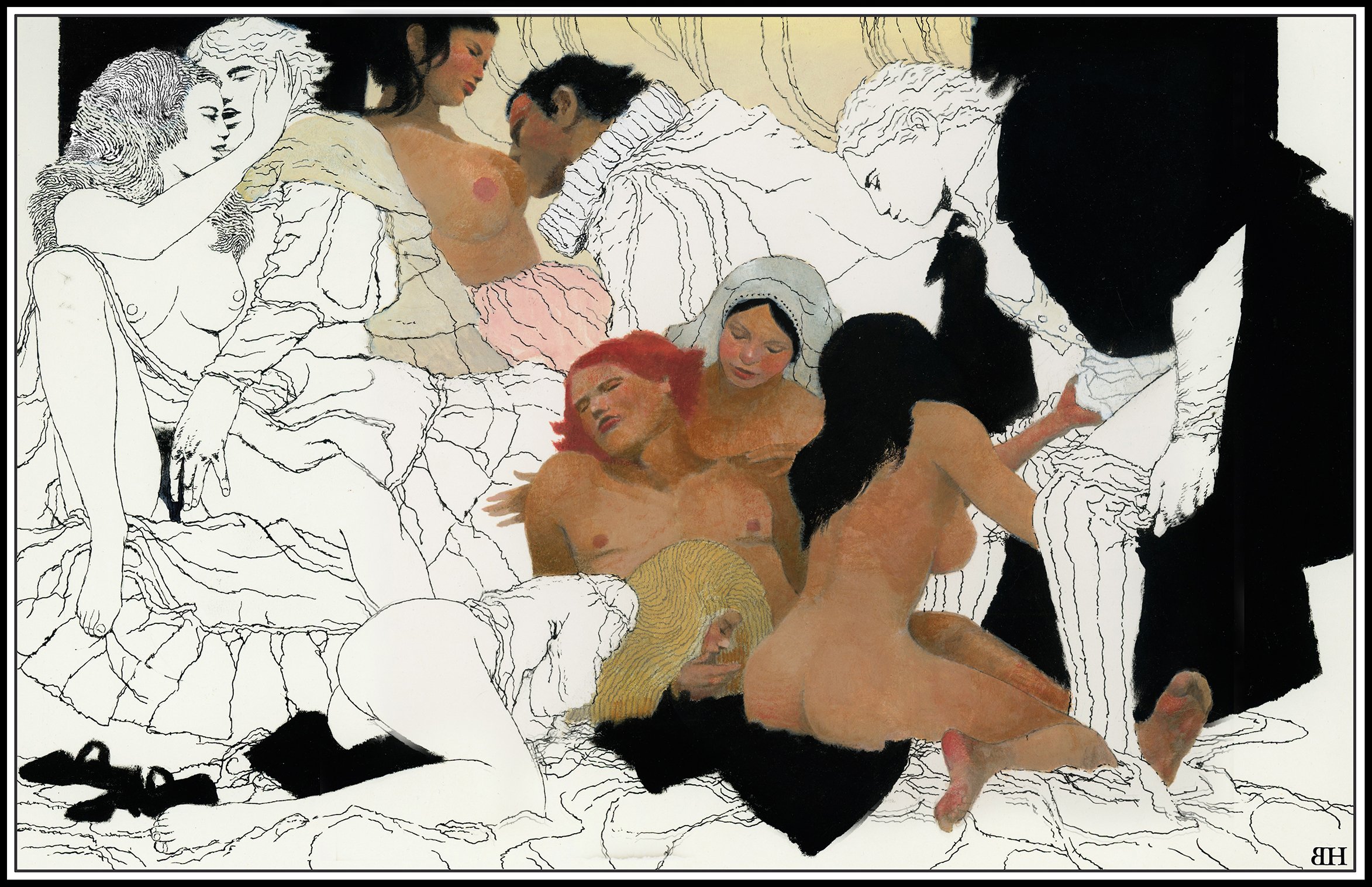

Above: Stewart, Towey, and Motley at the press check for the premiere issue of MSL; Towey and Stewart in a Texas cottonfield researching a story.

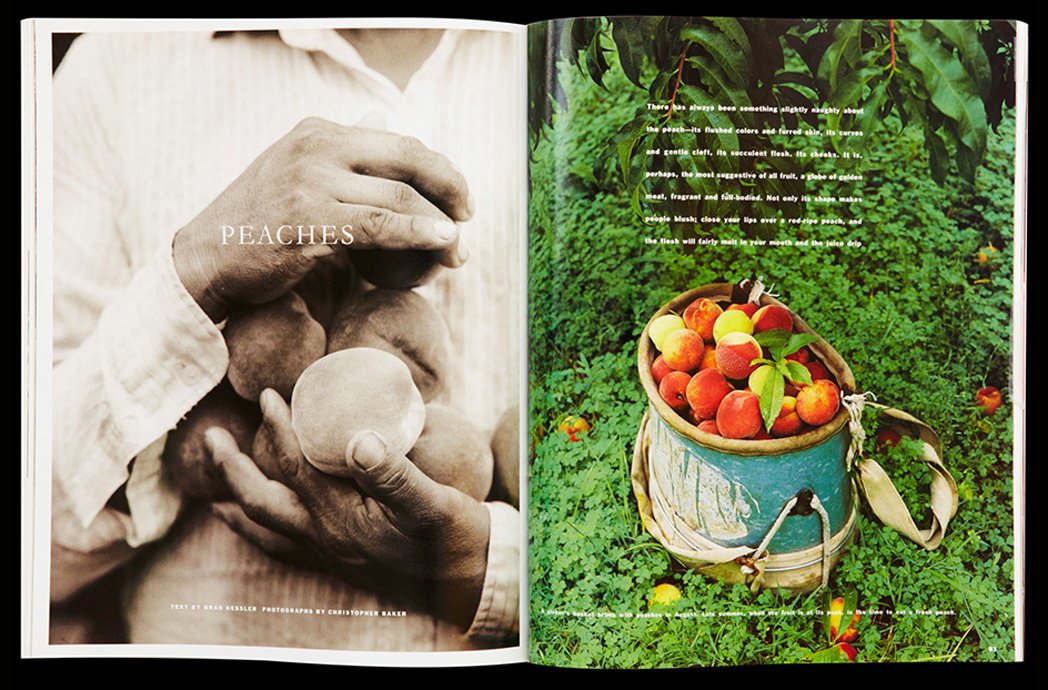

Patrick Mitchell: Which was just one of the many ways you guys reinvented storytelling for magazines. Can you talk about the process of creating one of your favorite glossary stories? The extremes you went to, to pull that all together because they were, like, ten spreads! They just went on and on, and never got boring.

Gael Towey: That’s such a good question. I love answering that question.

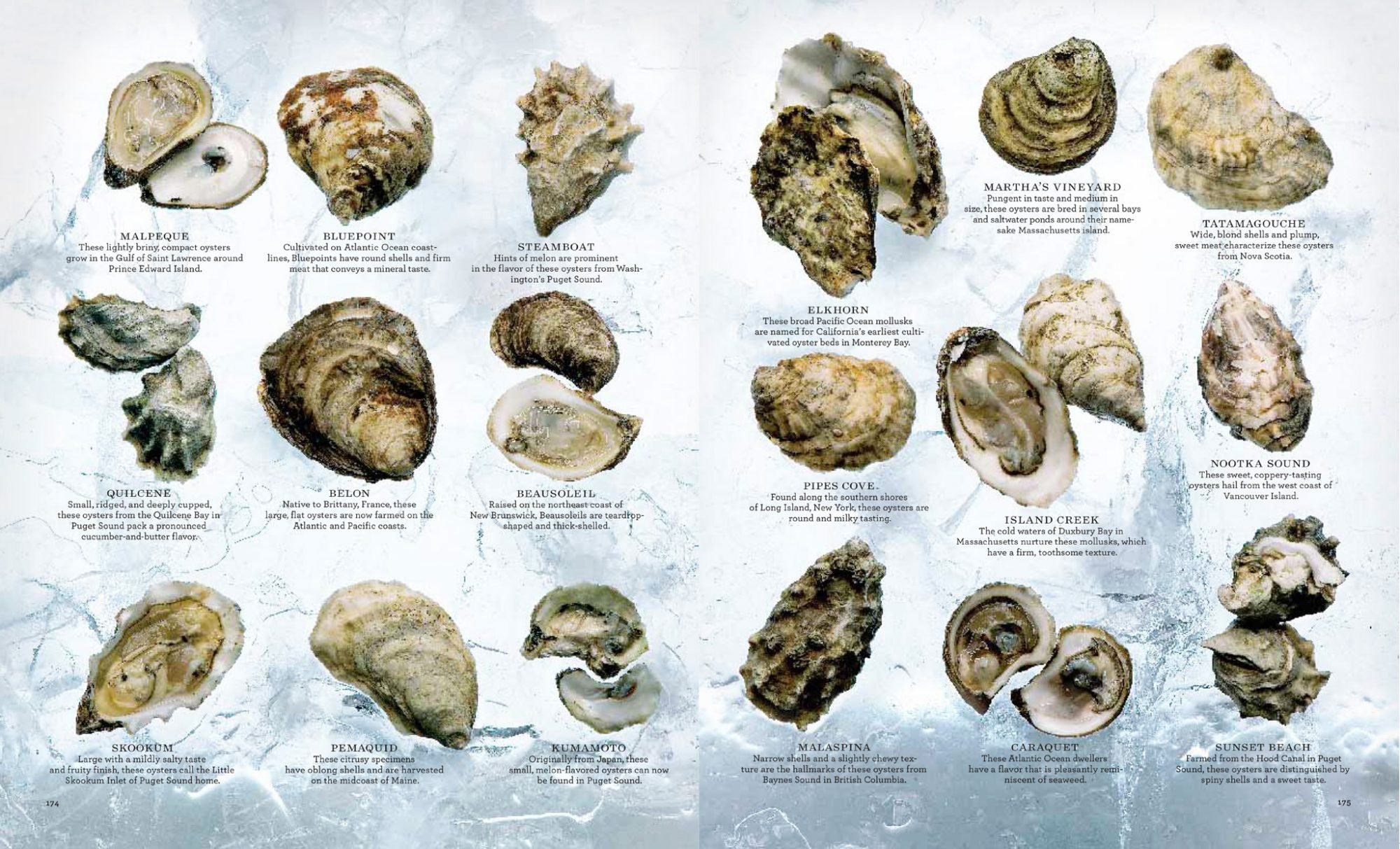

We would call in all of the figs, or the peaches, or whatever, from all over the country, and, you know, we grew so fast and we became famous really, really quickly, and so people were eager to pick up the phone. So we did get a lot of collaboration from growers.

But I remember when we were doing a peach story, my assistant, Paige Marchese, was having to call farmers around the country at, like, 10 o’clock at night because in the daytime they were working all day and they weren’t answering their phone or anything. But we watched, as, you know, there were floods in South Carolina and Georgia and there was a freeze in the winter in northern New York and Massachusetts. And the only place that the peaches were doing well was in California. But we were tracking this whole thing. We tracked it for the entire growing season just to get the peaches sent to Martha Stewart Living. And then everything was categorized by the food department. Everything was tasted. And then we hired Chris Baker to do the photographs.

I used to go into old print shops and look for seed catalog covers for inspiration and stuff like that, because the question, as you say is, “well, how are we going to photograph this glossary this time?” It was like a competition between all of the art directors, but everybody, it was their favorite kind of story to do because it was the maximum amount of creativity.

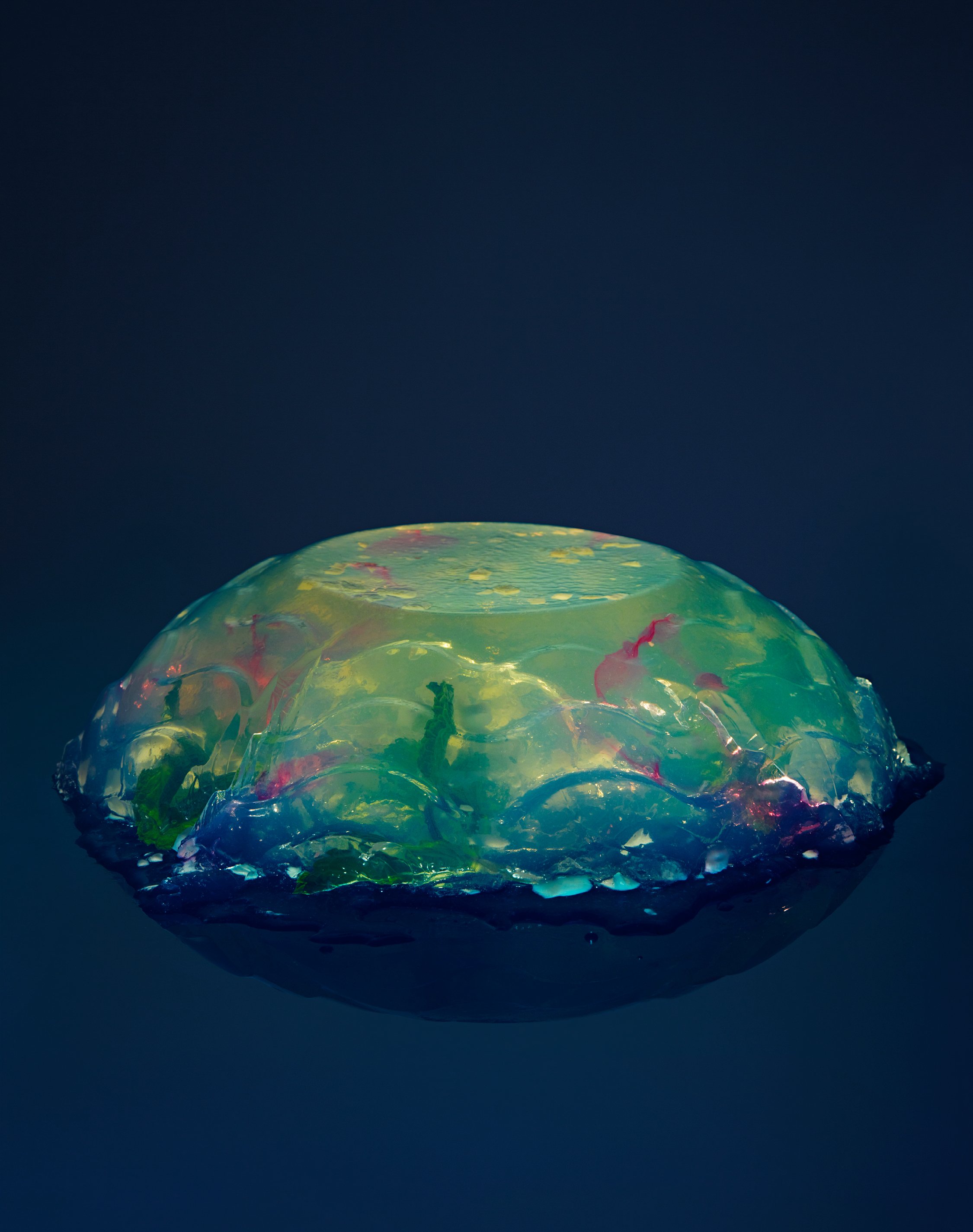

I remember doing a fig story with Maria Robledo, and we decided to paint backdrops, and we used this kind of Rothko idea of one color bleeding into another color, and then every fig was cut and opened and laid out on these big panels that we created. It was creating art. That’s what it was.

Debra Bishop: And so beautiful and so much fun to work on. When you think back on it, in one of the glossaries that I am fairly sure you worked on was the beautiful peony glossary. What were some of the favorite ones besides—the figs was beautiful. The peonies. Name some.

Gael Towey: But we did everything. We did rice!

Debra Bishop: Yeah. And the rice was amazing.

Gael Towey: She laid each piece of rice out like a grid! It’s insane.

Martha Stewart Living Glossaries

Debra Bishop: The early ones were beautiful too. That sort of set the whole tone and the whole format and motion. The apple glossary was stunning and amazing.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, the incredible thing is, what you just described was just for one-tenth of the magazine. You still had all that other stuff to do.

Gael Towey: That’s true.

Debra Bishop: It’s funny because I’m still making glossaries. I do it differently. I’m making glossaries with typography and information, but those photographic glossaries were, absolutely, cat’s meow.

Patrick Mitchell: And I assume you got a lot of great attention for that.

Gael Towey: We did. We won so many awards. Because they were really completely unique. Oh, I remember another—and people would come up with crazy stuff like , I think it might have been James Dunlinson, who did an oyster glossary. And, of course, we got oysters from all over the country—west coast oysters, east coast oysters—and we hired an ice guy to come in with this enormous block of ice. It must have been about eight inches thick. And it was probably 30 inches by, I would say, 18 inches. And all of the ice was kind of gouged out so that the oyster could sit in the ice pocket. And then he lit the whole thing from underneath. So the ice is glowing from underneath. And then there’s, of course, the top lighting.

We did some complicated stuff.

Debra Bishop: It was epic.

Patrick Mitchell: Imagine doing that for a website.

Debra Bishop: Those should somehow be framed and they should be put in a gallery. They’re incredible.

Patrick Mitchell: In the time before Martha Stewart, the legacy power structure in publishing meant that magazine editors were absolute monarchs. You and Martha changed that. And we all owe you a debt of gratitude because, for the most part, before the success of Martha Stewart, designers didn’t really have a seat at the table. Or, at best, we had a limited role in shaping the content of our magazines. I’m fairly sure this was part of your master plan, but can you explain how and why the process was different from other magazines?

I mean, I would say it’s partly the nature of being a startup. It was kind of the same thing at Fast Company. We didn’t have a lot of “magazine people” there. We were just a group of people with an idea figuring out how to make it happen. So you had the sort of freedom to create the structure you wanted. But how did you go about doing that?

Gael Towey: We did have the freedom to create the structure we wanted. And when Martha asked me to be the art director, I said, “I want to be on the same level as the editor. I don’t want to report to the editor. I want us to be a team.” And she agreed with that. She, of course, was the last person to make a decision, but she didn’t function like an editor in chief.

That wasn’t really her role. The whole idea of teamwork, as I mentioned, came out of my realization at House & Garden that you’re stifling creativity by keeping everybody in a separate, isolated role. And the thing that I miss the most about working at Martha Stewart Living is that collaboration. The fun of it all. The fun of coming up with ideas, the fun about learning from people.

I learned so much about gardening and cooking. And I learned not to be afraid. You just try something. And that’s kind of a big deal.

Patrick Mitchell: You paid it forward because, from everything I’ve heard, from Deb’s description, that style of collaboration trickled down to all the different departments, designers, editors, food stylist, prop stylists, crafters, gardeners …

Gael Towey: Well it trickled down, but also, it became the way we organized all the other businesses. And since this is about print, maybe you don’t want to talk about all that stuff.

Patrick Mitchell: No, we do.

Gael Towey: The catalog that Deb was the art director of with Fritz [Karch, MSL’s Collecting Editor], Martha by Mail, they were a team figuring out products, inventing things, creating a style of catalog that became the style of all catalogs. A lifestyle of catalogs, because they used that how-to idea, that inspiration idea, that we established in the magazine for the catalog.

And then from there we went on and did the same thing with Kmart. And the same thing with a lot of the other product businesses. And none of us had ever done any of that before. One of the things that was great about working for Martha is that she didn’t do that stuff before and she thought that she could do it, so she just figured that everybody else could do it too.

“When we started Martha Stewart Living, I wanted to have a team. I wanted to be with people. I wanted to have friends. You know, I wanted to have a working relationship with people. I didn’t want to be isolated in some room, and then after they beat you up all day long, you get in your car service and go home.”

Debra Bishop: Yeah, she wasn’t afraid of trying anything new. And that was a wonderful sort of incubator for creativity. And Martha by Mail was my favorite job that I have ever had. It was! Because not only were you branding, getting the experience of photography, and learning, going on photo shoots, learning how to be an art director, but you were creating products.

Now, nothing’s better than that. And I don’t want to say too much, but it brings up this whole concept of the magazine being the research area that everything else spun off of. So for instance, if the magazine created this amazing story on family trees, then at Martha by Mail I would get to create a product, a beautiful family tree that was inspired by the actual article in the magazine. But actually make a physical product that we could sell. Now that is really fun for a designer and art director.

Gael Towey: Yeah. And look at you now. Now you’re doing this amazing kid supplement at The New York Times, and you’re utilizing all that—you’re inventing that product from scratch. It’s very similar. Very similar.

Debra Bishop: I still think of what I’m designing as a product, which it is. But I go a little further.

Gael Towey: Deb, can I remind you about your interview with Martha? When we first hired you?

Debra Bishop: I knew you were going to bring this story up!

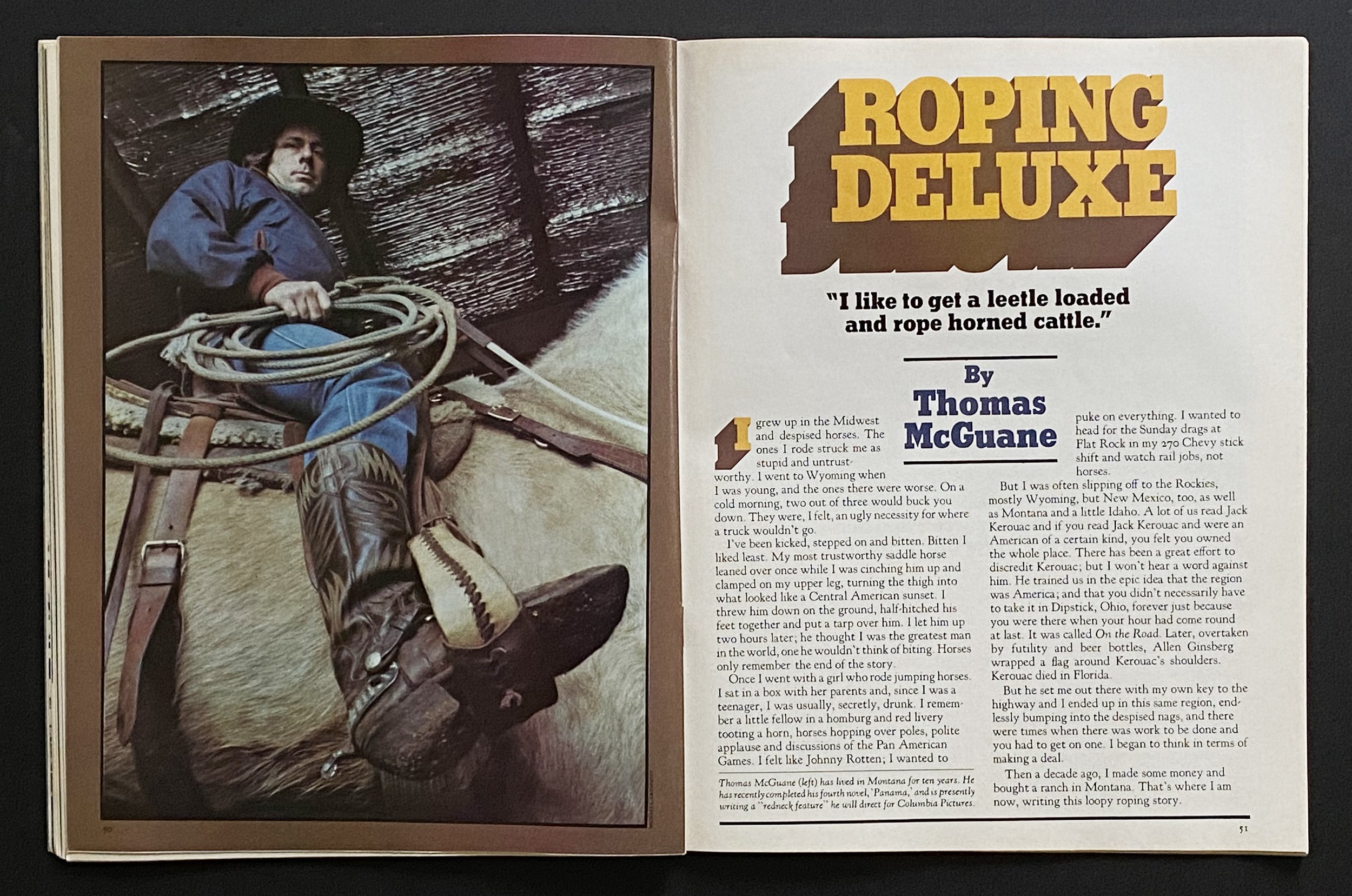

Gael Towey: I love this story. I really love this story. Okay, so Deb Bishop is this premier type designer and she comes in with her portfolio, and she’s coming from Rolling Stone. And Martha’s there to meet Deb because I said, “I found the right person. We really want to hire Deb Bishop.”

And Martha’s like, “Well, I have to meet her.” And this is to do the Martha by Mail catalog. So, Martha looks at the first two pages of Deb’s amazing, amazing Rolling Stone work. Incredible typography. And she closes the portfolio and pushes it back to Debra and says, “Well, you can’t do that here, so what are you going to do?”

Debra Bishop: And I did not know how to respond to that, but luckily Gael was behind me and supportive and did hire me regardless. Anyway, it’s a very funny story. I think I mumbled something like—I don’t think I said anything! I can’t even remember. Anyway, funny story.

Gael Towey: I think one of the reasons that you were such a good art director with photography is because typography is about balance, and texture, and emphasis, and design of the whole page. And photography is the same thing.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. It’s really about design. I consider my Martha Stewart Living days like working in a creative factory. Everything you needed to create a story was in house: props, photo studios, a set building shop, a test kitchen. Sometimes a wonderful smell would drift by my desk, and I’d be, “Hmm, is that baked apple pie or is it Martha’s favorite brownies? Maybe I’ll walk over there, see if I can have a little taste.”

Inspiration was always at hand simply by walking by the style department, or the craft department, or even the collecting department. Do you think that there’ll ever be another company like it?

Gael Towey: Probably not. It was extraordinary. It really was. People described it as “Santa’s factory.”

And remember how many tours we would take people on? It was in this incredibly beautiful, modern building—the Starrett-Lehigh Building—that was built at the turn of the century and it had rounded walls and incredible light because it’s right on the Hudson River.

But Fritz would go out and collect things for his collecting stories. We had a whole room of props. And all the shooting studios were right there. So you were constantly being educated. And a lot of people did go through Martha Stewart Living. And part of the reason a lot of people got hired away is because they were so well trained and they were trained in everything across what you just mentioned.

Because most of the time in a magazine, because it comes out either weekly or monthly, you’re kind of stuck in a job that’s like a cog in the wheel. And you just do that same job over and over and over again, every single month, in order to get it out on time. But that’s not the way we worked.

Patrick Mitchell: I’m glad you brought up the building because I never went up there, but I heard stories about it. And I assume you were involved in the design—that was not where Martha originally was. You made a big move into that building as you grew. But were you involved in the design of the space as well?

Gael Towey: I was. I worked with the architect. And that was really fun, too. When I think about all the different things that I got exposed to, I was so lucky.

I had never designed products before. I never designed packaging for products. I never did national advertising. I never did sales material for signage in stores. I never did any of that stuff. And then I got a chance to do it all. And even the presentations, you know, thinking about the glossaries, those glossaries influenced us in so many ways. I remember when we did the holiday product at Kmart, we did glass bulbs in every single color.

And An Diels who was the art director on the product side, created this glossary of Christmas balls. And every single color gradated, by color, all the way down the hallway as you entered into the space. It must have been 40 feet long, and every single color gradated according to the color spectrum. It was unbelievable.

Debra Bishop: It really was.

Patrick Mitchell: Gawd, publishing was so fun when there was money!

Gael Towey: I know. We’re very lucky that we experienced that.

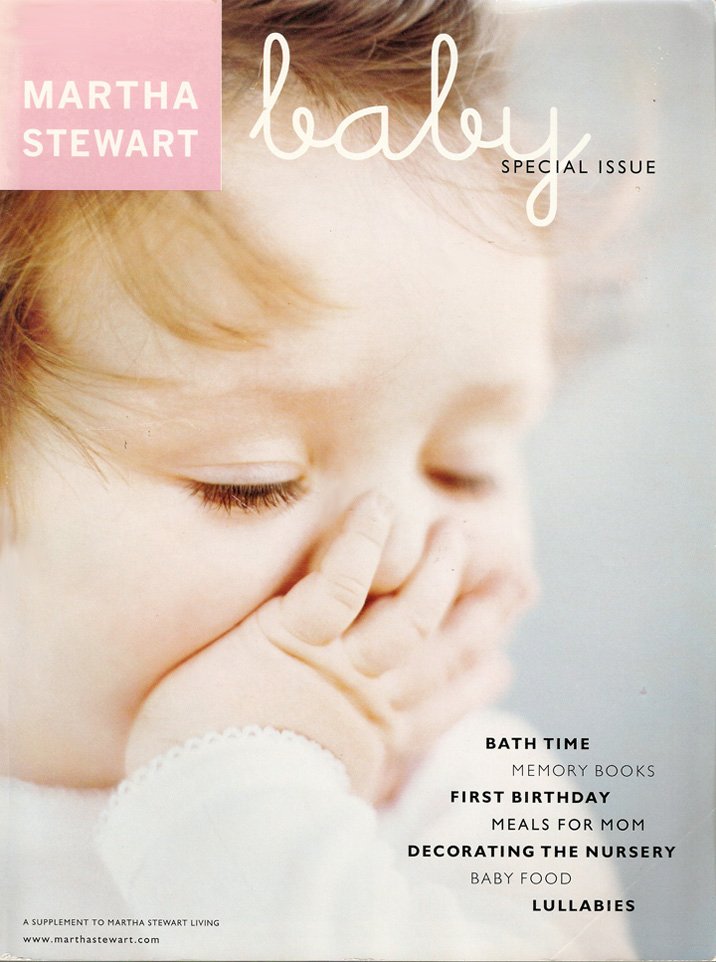

Patrick Mitchell: So the magazine was a huge success, and it grew and grew and grew. The centerpiece was the magazine itself, Martha Stewart Living. But as you’ve talked about, there were offshoots. There was a mail order catalog, Martha by Mail. You had a book division. You did a weddings magazine, a kids magazine, a baby magazine. Everyday Food, which was a recipe magazine. And then this whole side gig with Kmart, which played a huge role in the massive expansion of Martha.

And we all know about that. Everybody knows about the business. But I want to talk about it from the perspective of you, Gael Towey, as one woman overseeing this incredible amount of work and all of these people. Can you talk a little bit about what your approach was to surviving this massive beast of a company?

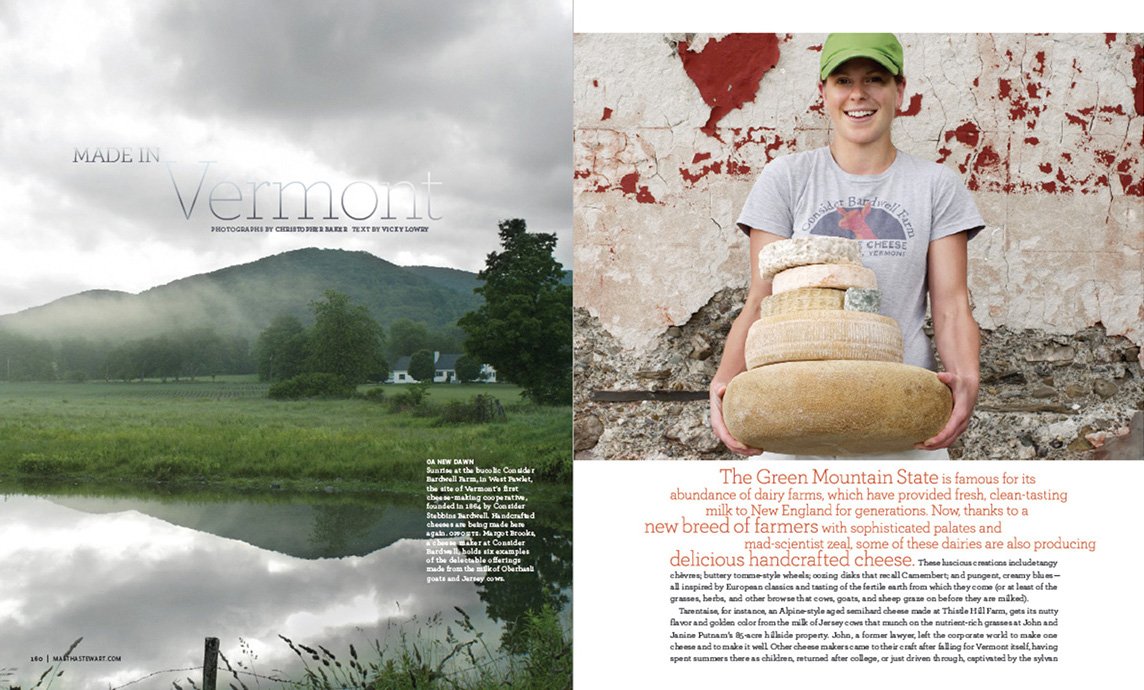

Gael Towey: Well, I loved it. I really did love it. And I was very well aware of the privilege that I had of being—Martha used to describe me as “first in, first out.” You know, go in, set it up, figure out who to hire. And I used my principles of the type of people that I like to hire for the magazine as the type of people that I wanted to hire for the other product businesses. I wanted people to be collaborators as well as being talented. Obviously, they also had to be talented.

I also wanted them to have a little bit of knowledge of art history. That was something that was a real bugaboo with me. I wanted people to know about art. And know where it came from. So hiring, spotting talent was probably the most important thing for me because we grew so fast and we had to hire so many people and they had to be inventive, and have a good color sense, and be able to follow through, and all of that.

You know, the other thing, in terms of going back to the different type of structure, for most of the life of the company, when I was there, I was in charge of all the people who were the creatives. And they reported to me through their different bosses and so forth.

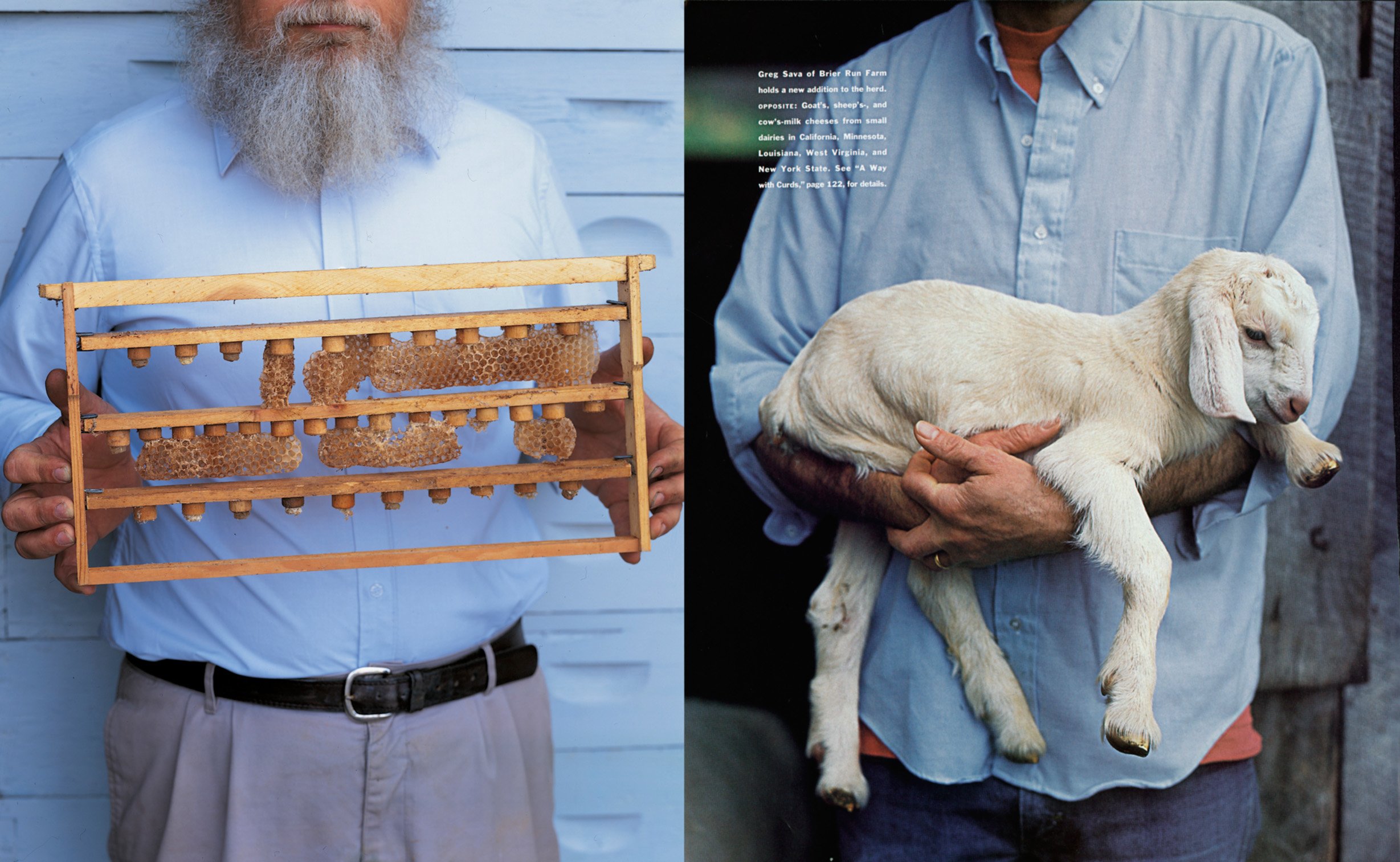

And it kept all the creatives working together. But it was also a very, very different structure. You didn’t have a business head of the product departments who were in charge of the art directors. It was the art directors who were in charge of the art directors. So they really understood that and they understood branding, the branding, the whole idea of hands, and hands holding things and all of that. That kind of evolved, those brand definers, evolved out of the magazine.

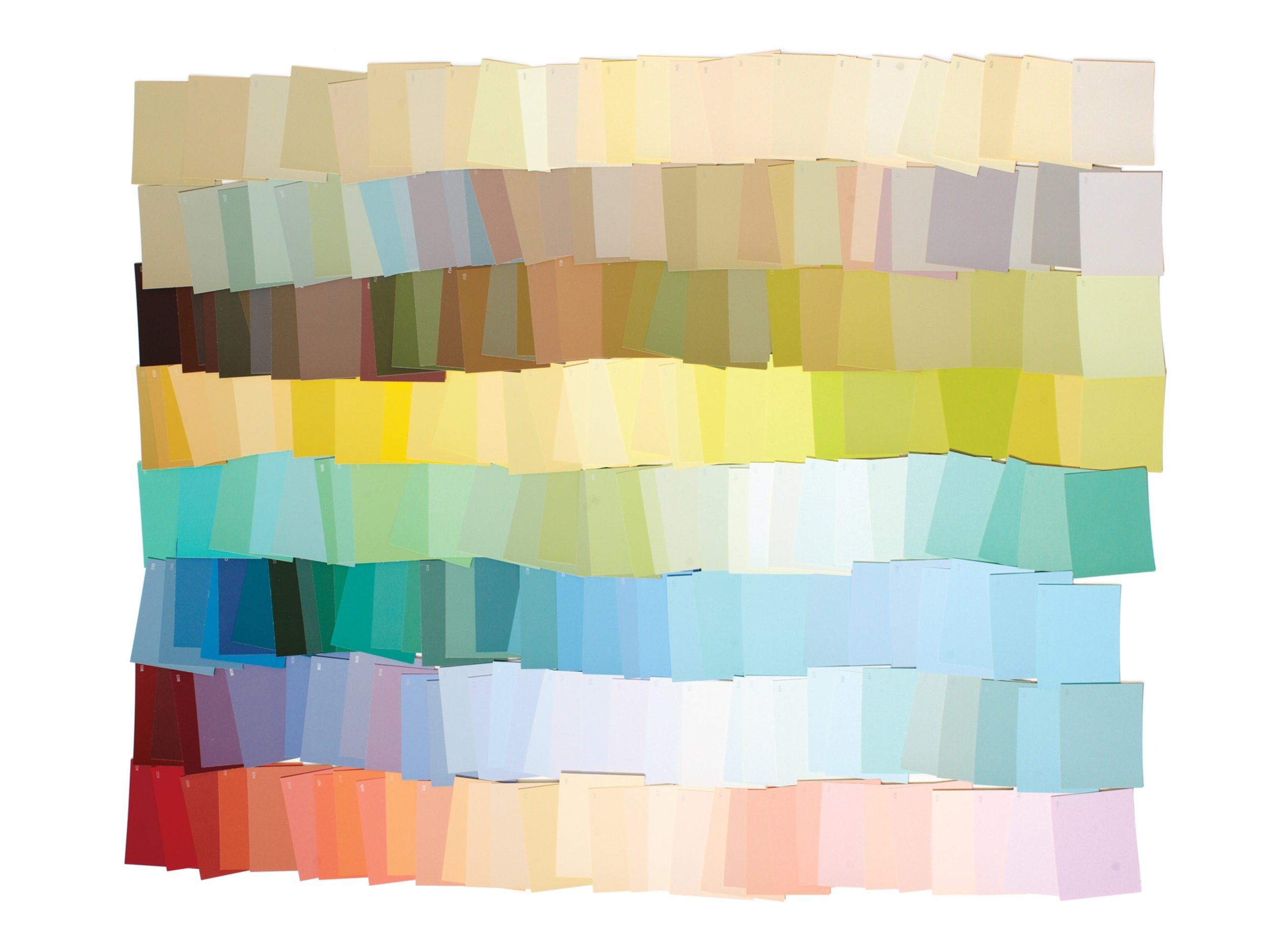

And the whole thing of starting it yourself and doing it yourself evolved out of the magazine. So when we did 280 paint colors for Kmart, we were starting from, you know, Martha’s favorite colors on Martha’s favorite dishes and colors from the garden.

And we hired a painter who would come and make paint swatches. We had thousands of paint swatches that we made into a final palette for Kmart. But we started with actual paint. We weren’t going to other stores and getting paint swatches off the walls. It was all so original.

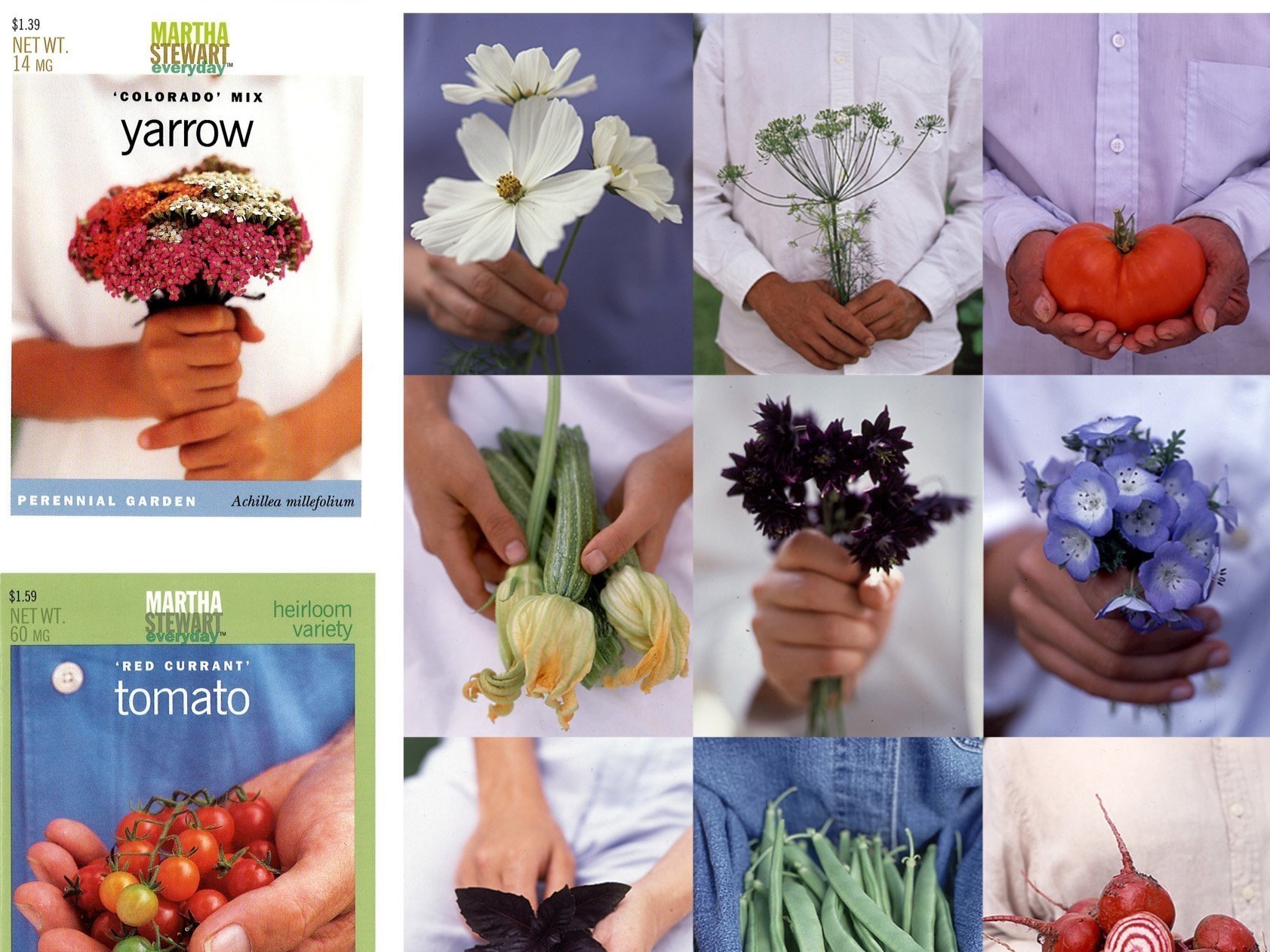

And when we did the seeds, Martha wanted to grow every single seed in her garden. This was still in Westport. She cleared some land. We planted every seed that we were going to sell. When they grew into flowers, we had them held in hands so that you could see the scale of the flower.

And so the flower would be isolated and you would see what it would look like. And nobody did that. It’s kind of unheard of that we would have that kind of control. But we were reaching 72 million people, and that Kmart deal was the thing that really brought Martha to the fore.

“One of the things that was great about working for Martha is that she didn’t do that stuff before and she thought that she could do it, so she just figured that everybody else could do it too.”

Patrick Mitchell: You scaled your management style, you know, well, your design style, you scaled that with the company. And it’s really a survival mechanism that, “these are the rules in place.” Like when Martha told Deb she could never work there ...

Gael Towey: She said, “you can’t do that here,” right? You can’t do that, can’t do that here.

Patrick Mitchell: But that was her way of saying, “this company is so big, we have to have a way of doing things, or we won’t survive.”

Debra Bishop: Obviously, Gael developed a lot of these systems that actually really worked out so beautifully for all of the extra projects.

Gael, your job became huge. It really did. It was a huge job. The bones of the company and the bones of the research for the magazine then actually helped expand and brand the other areas of the company. So it was a huge job, there’s no doubt, and so incredible. I don’t think there will ever be another company exactly like that. And then along those lines, I just wanted to ask you a question that I get asked a lot.

How did you deal with balancing motherhood? You have two children, Maud and August. With the long hours, and the stress, at the helm of a big creative company. How did you balance that?

Gael Towey: It was hard because, as you know, in the creative world, you never stop working. You never stop looking. Weekends I was dragging my children around to antique stores.

Meanwhile, today, they’re so picky about everything. They were kicking and screaming, but they certainly get it now. I remember once—Martha used to call me all the time. It would drive me crazy because she’d called me at, like, eight o’clock in the morning while I’m still at home and I’m trying to make lunch for the kids and get them to school.

And the phone would ring and it would be Martha. And this is, of course, before cell phones, so, you know, you’re on a line and the kids are crying and they come up to you and they’re crying and crying. And I’m like, “Martha, I can’t hear you. Can I call you back?”

“Well, what are you doing? What is that? What is that racket?”

Anyway, I thought, “You know what? I’m just going to hold the phone really close to all the crying so that she can hear this.” She never called me at eight o’clock in the morning again.

Debra Bishop: But basically you brought them along the journey.

Gael Towey: I did, and I brought them to photo shoots. I’ll never forget this photo shoot in Florida. Going back to some of your original questions about what were the hard things that you had to do when you first started the magazine?

Time Inc. gave us the money to do the first issue and then we had to wait around for them to approve a second issue, and then they had to do their calculations, and counting newsstand sales, to give us permission for the third issue. Until, finally, after six months of testing—we weren’t able to shoot for the following year, so we were constantly, in the winter time, shooting summer and so on and so forth. Anyway, I brought Maud to this beach location and I was pregnant with August and the beach was so hard and I was running. We didn’t have—I don’t know what we were thinking—but we didn’t have walkie talkies.

I was running back and forth from one place to another trying to keep this shoot together, which was spread out across three beaches and two houses. Oh my gosh! I got into bed at night and I was sleeping in the same bed with Maud, who was, I think, probably four years old. My legs hurt so much I can’t even begin to tell you.

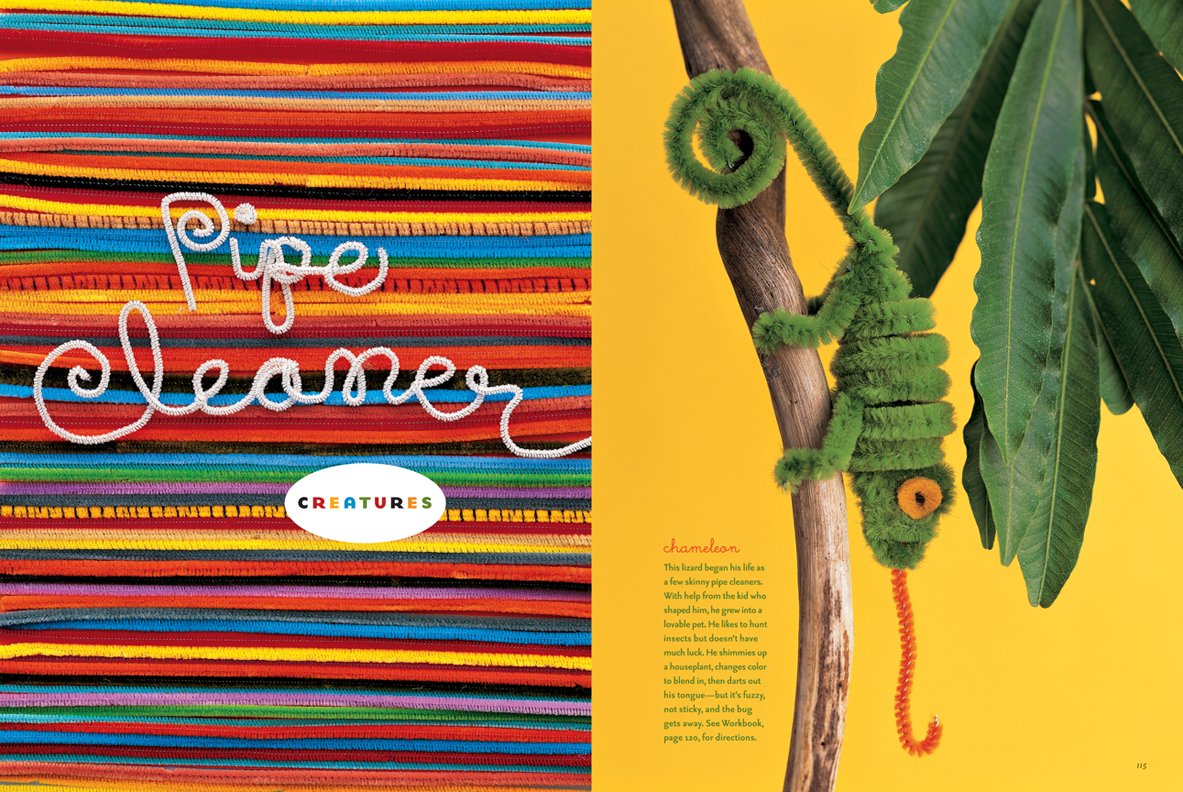

Anyway, I was young and healthy and I felt like I could do anything. And, because you did the Kids magazine, we all sort of grew in this subject matter because we were experiencing it in our life.

Debra Bishop: And that was one of the greatest gifts that I had. Yeah. I was able to, as I was having children, I was helping create content about the very subject right.

Gael Towey: Which is why it was so good.

Debra Bishop: Exactly. I mean, for me it was good because I had that creative outlet. I was interested in the topic. And so many of my collaborators at Martha Stewart Living were having children. And we were all balancing. And we were all one big family. Our kids would model. Or they would test.

Gael Towey: They were all in the photo shoots. Who was the baby? Was it Andrea’s first child? Who’s the baby in the bowl for the Baby mag?

Debra Bishop: Oh, that’s Andrea’s Lula. And that bowl, the bowl idea—I loved that enamel bowl. We were selling it at Martha Stewart, and we were all like, “what are we going to do with that bowl?” And I said, “I know exactly what we’re going to do with that bowl.” Because my brother used to be bathed at the cottage when I was growing up. And I have these beautiful pictures of my mother bathing him in an enamel bowl just like that.

So that’s where the idea came from. But when we shot it, and this was when Andrea and I were both very young mothers, and we put Lula in this bowl with water in it. She loved it. And it was on top of a very narrow table that we had in the shoot studio. And when I think about it today, I just, like, cringe because it was such a dangerous thing to put a little baby in a bowl like that on a small table and then step back to take the picture.

And then the other thing was, Martha loves to tell the story where Lula loved the bowl so much, it was nice and warm in there, that she pooped in the bowl. Martha loves to tell that story, but behind the scenes you couldn’t luckily see it on the catalog cover.

Patrick Mitchell: So, last Spring Dotdash Meredith, which is some amalgamation of what used to be Meredith Publishing, decided to end Martha’s print life. And they killed it, along with several other thoroughbred brands. How did you feel about that? Seeing the end of Martha in print?

Gael Towey: I mean, obviously, I wasn’t surprised. Because so many magazines by then had folded.

Patrick Mitchell: But this is your baby.

Gael Towey: But after I left, I obviously watched it for a while. But I felt that the restrictions, being under Meredith, had really changed the magazine. And I didn’t feel that it had the same emotional connection that it had had earlier.

So, I certainly felt sad about it. But mostly I felt sad for the people who were working there and really loving doing their jobs. I felt terrible about that. But you have to remember that when I left at the end of 2012, I had just gone through this very excruciating experience where I had to fire a lot of people and it was so devastating for me.

I was firing people because we were losing money and there were a group of executives who had taken over. And the thing about Martha going to jail is that she was forced to be away from the company for about a year.

And then she wasn’t allowed to be on her own board of directors anymore. And so, for something like 10 years, the board and the company itself were doing things that were, frankly, really stupid. They closed her television show. And it was like the place was self-destructing.

So for me, because in 2011 and 2012, we were really suffering so much and I knew they were going to fire even more people and I didn’t want to be there to go through that all over again. It was too horrible to fire people who you loved, who you cared about, who were your friends, who you hired and trained yourself, and who were, I thought, geniuses.

And have to go through that all over again. I couldn’t do it. So for me, that was the big break. That was a horrifying time.

Debra Bishop: And you had to remove yourself emotionally from it at that point. So by the time Dotdash got a hold of it, it was already gone.

Gael Towey: It was already gone.

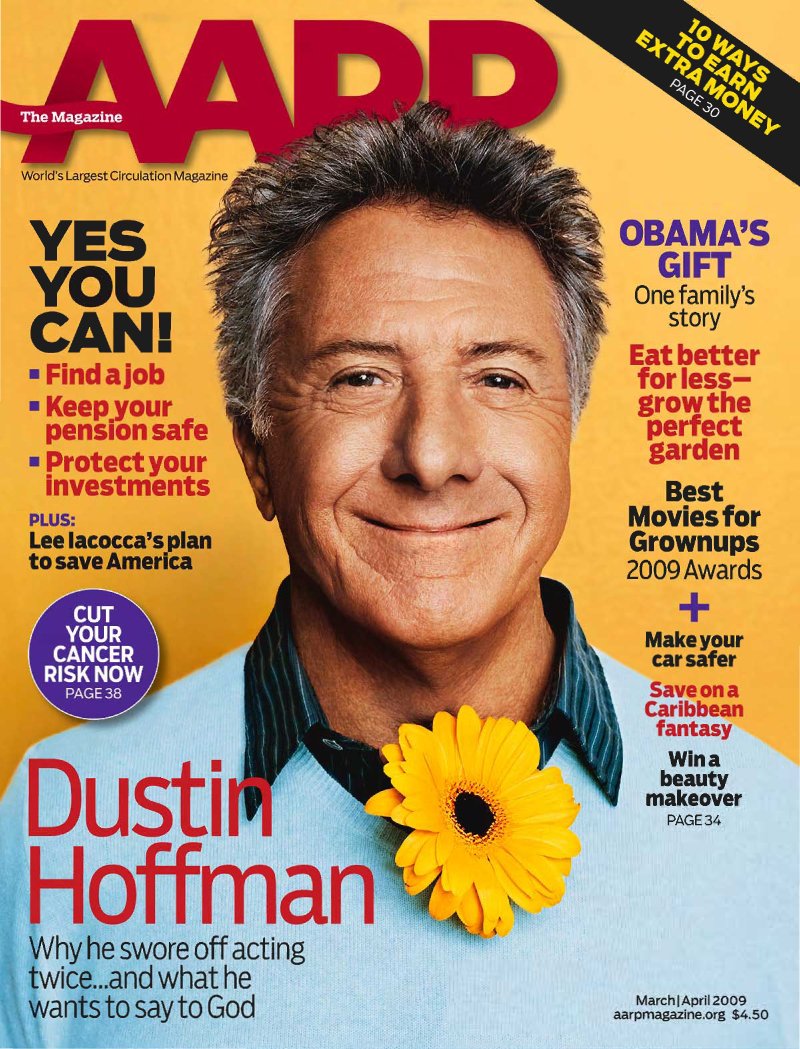

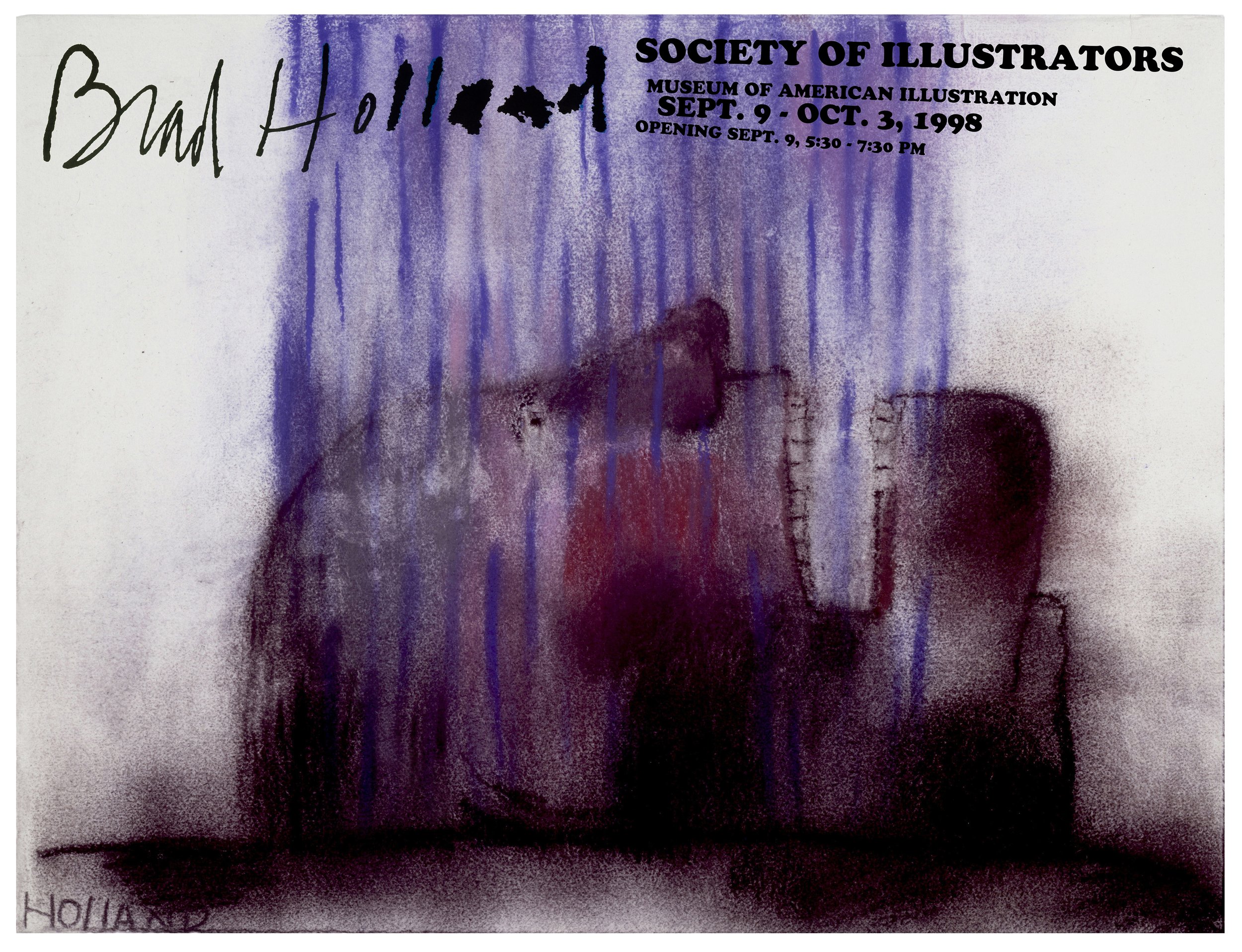

Debra Bishop: For those who don’t know him, can you tell us about your husband, the fabulous designer Stephen Doyle?

Gael Towey: Stephen’s very funny. He is a wonderful dancer. He’s an amazing father. He’s an incredibly generous person. He’s very, very inventive. He’s constantly thinking of things to make. He’s a maker. And he loves to do the things that I love to do, which is to travel. I really like educating myself constantly and having new experiences, and he feels the same way. We both love art. We love going to museums. We love shopping in antique stores and flea markets. We love to cook, and we cook together.

We’ve had a number of experiences working together. Stephen designed the Kmart logo and all of the early packaging for Kmart. And during the day, I would be in the office working with all the product designers and hiring people, and we were doing thousands of products almost immediately and getting Martha to approve the color swatches and the fabrications and all that kind of stuff.

And then I would come home and Stephen and I would spread all the packaging concepts out on the floor of the living room. And our children would say to us, “do you guys ever stop working?” In other words, we were paying no attention to the children.

Debra Bishop: I’ve had the same experience.

Gael Towey: We were having the time of our lives, looking at packaging and logos. And he was coming up with all these crazy ideas for these packages that would fold so that you could see the shape of the wine glasses. But you had to look through the glass to see the typography. And of course, because you’re looking through the glass of the wine glass, the typography was a little wobbly in this really cool way. So it was so fun. So fun. We really, really, really had such a good time.

Debra Bishop: You’ve already talked about when you first met, which is hilarious. So I’m assuming it wasn’t love at first sight. Or was it?

Gael Towey: Not for me. I was a mess. In fact, Martha would come into the office and say, “What’s wrong with her? She’s losing weight. She’s losing too much weight. Tell her to stop. Tell her to stop!” And, you know, I was a disaster. Anyway, it took me a while.

Debra Bishop: But tell us about your first date. Where did you go?

Gael Towey: We went to a photographer’s loft who was having a Christmas party. And she had a live band. And we danced. We each went separately, but we both knew that we would see each other there because we both knew that we were invited. And we danced together all night long.

And he’s a really, really good dancer. And my father was also a great dancer. And I learned how to dance from my father.

Debra Bishop: Wow.

Gael Towey: And I danced with Stephen and I thought, “Oh my God, I could marry this guy.”

Debra Bishop: Did you propose?

Gael Towey: No, he proposed.

Debra Bishop: And?

Gael Towey: He proposed. And we decided to get married very, very quickly. And for Christmas, our first Christmas, he gave me this wrapped package, and it was this big heavy paperback and I’m thinking, you know, “Why do I have the Tale of Two Cities? Like, what is this?” And I opened it up and inside he had cut out all the pages and there was a little ring box in there.

Debra Bishop: Wow.

Patrick Mitchell: I was going to ask you if he took a knee, but it doesn’t even matter.

Debra Bishop: That was pretty amazing.

Gael Towey: Yeah. Pretty amazing. And, I’d have to say, in terms of design, that I’ve really learned a lot from Stephen. As I said, I am not a typographer. I’m much more of an image maker, and he is an incredible typographer. And I have learned so much from watching him work in that way.

Patrick Mitchell: I imagine the idea of you two going into business together has come up, from time to time.

Gael Towey: That would be horrible.

Patrick Mitchell: Really?

Gael Towey: It would’ve killed our marriage. I mean, it was fun to work on the isolated thing, you know, a logo or something like that. But Stephen sees the world in a very, very specific way, and that’s what he sees. He’s in his own business, running his own business for a reason.

I think he was fired from every other job he ever had. Actually, he asked Tibor Kalman at M&Co., for a raise, and Tibor said no. And so he quit. But otherwise he was fired.

Patrick Mitchell: I read an interview with you and your fellow BU alum, Julianne Moore, where you said, “if you let your passion lead you, you’ll discover the wonderful things you can do. I think a creative life is a whole life. In a creative life, you never stop working. You’re always looking, you’re always learning. Lifelong learning is one of the most important things you can do for yourself and the people around you.”

Talk about how that has unfolded in your life.

Gael Towey: Well, when I left Martha Stewart at the end of 2012, I really didn’t know what I was going to do with myself.

And after about six months of having lunch with friends, and hanging out and stuff, I decided to start doing videos. And the reason for that is because I love storytelling and I realized that what I wanted to do was storytelling. So I started shooting. I’d never done, I mean, I did videos obviously at Martha Stewart Living, and all of us were on television, so we were pretty comfortable with TV.

And when we did the first digital magazine, we were able to do video and incorporate them into the digital magazines. So I had some experience with that. And I didn’t want to do the classic Martha Stewart subject matter. So I ended up doing videos with artists who were friends of mine, in order to kind of get used to it, and establish this little teeny business I have now called Portraits in Creativity. And it’s all about telling artists stories.

Debra Bishop: I saw the Gabriella Kiss film, which I love so much, Gael.

Gael Towey: Thank you.

Debra Bishop: One of your subjects, Natalie Chanin, the noted fashion icon, interviewed you for her website. In that interview, you say, “My career has been fulfilling, but I have to say that the relationships I have built and the people I have met are more inspiring to me and more important to me than any particular designer product I had a hand in creating.” Aside from your family, who inspires you?

Gael Towey: Gosh, I have so many wonderful artist friends. And one of the things that has been such a privilege for me in doing these videos is meeting people that I’ve never met before, and finding them so inspiring myself. To be able to read their books and then interview them.

There’s something about being with a camera across from somebody and how honest they suddenly become and how it allows you to ask questions that are so deep. I’ll never forget interviewing Roseanne Cash, who, before I did the video with Roseanne, we had already been friends for 15 years, but I was able to ask her questions that were so much deeper than the casual, go out to lunch sort of relationship that we had.

And to be able to get into somebody’s creative life and find out what really makes them creative, what they go through emotionally, how they train themselves, the discipline that they bring into their lives and their way of listening for inspiration. People don’t realize how much research it takes in order to be inspired. In order to be ready to be inspired. In order to be ready to listen.

And Alabama Chanin’s story about standing on a street corner in New York City after having failed to sell her designs to any New York company. She’s looking at her t-shirt that she designed, which she hand stitched together and realized, “Oh my God, I’m in the wrong place. I have to go home to Alabama because that’s where all the stitches are.”

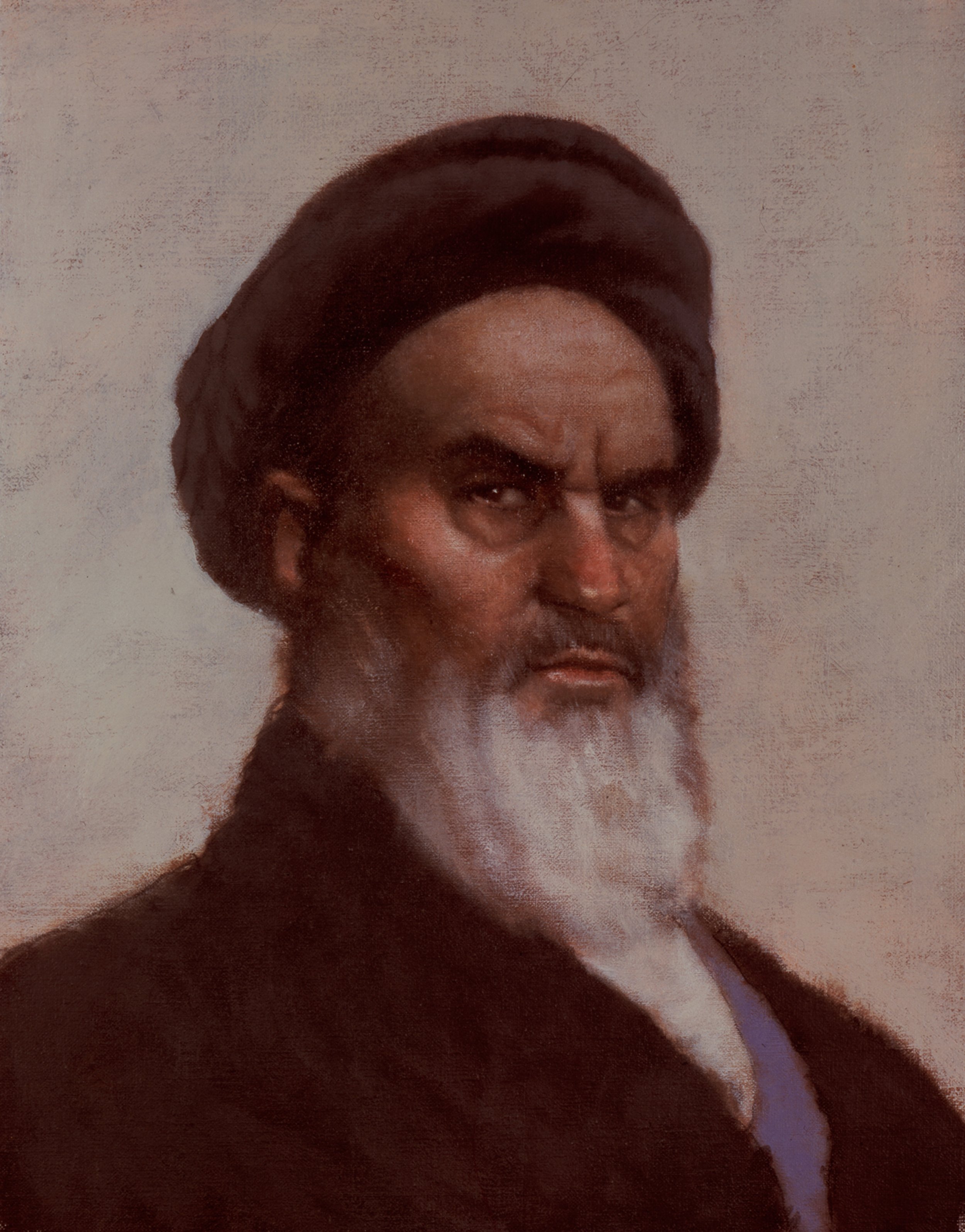

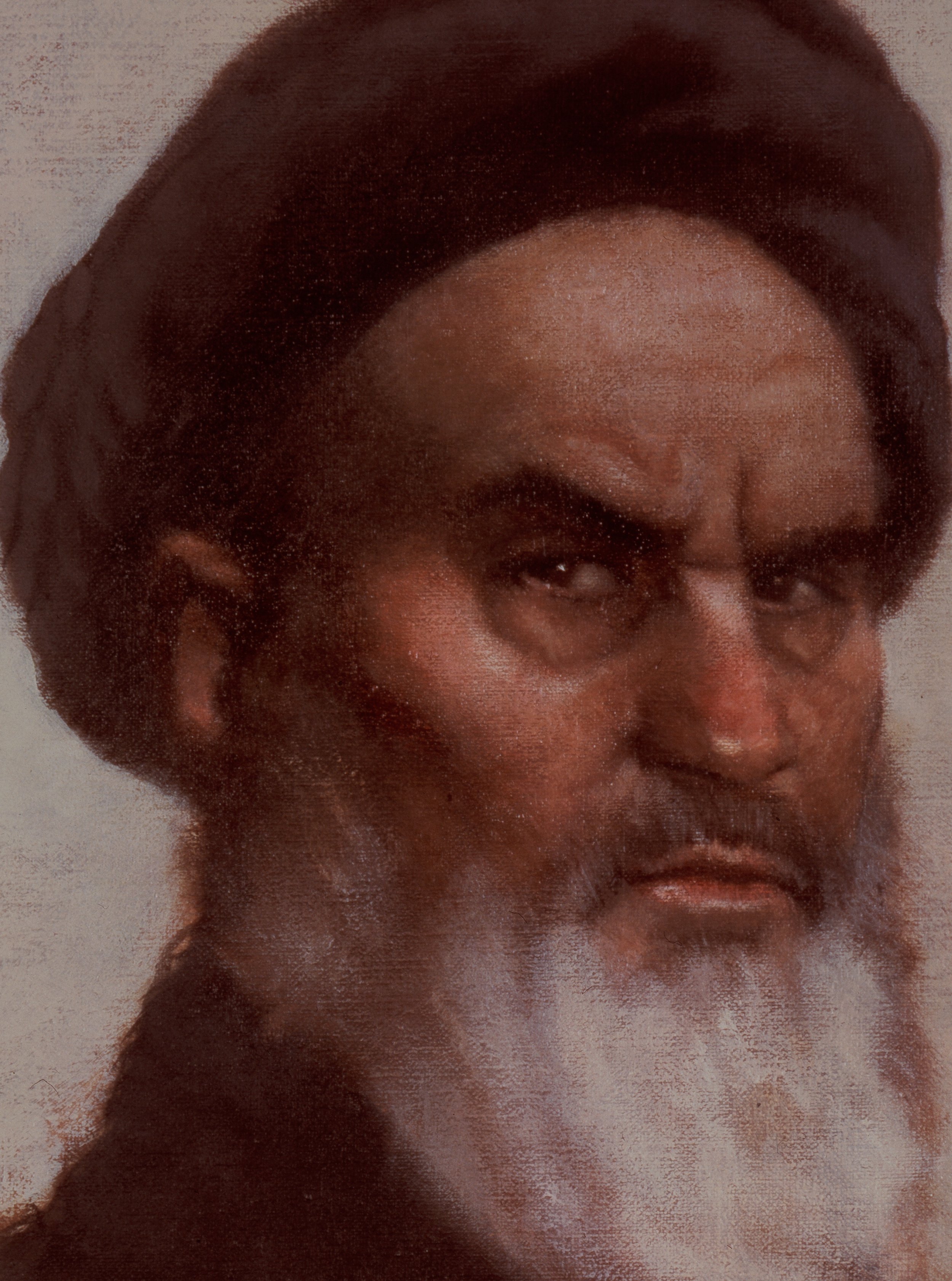

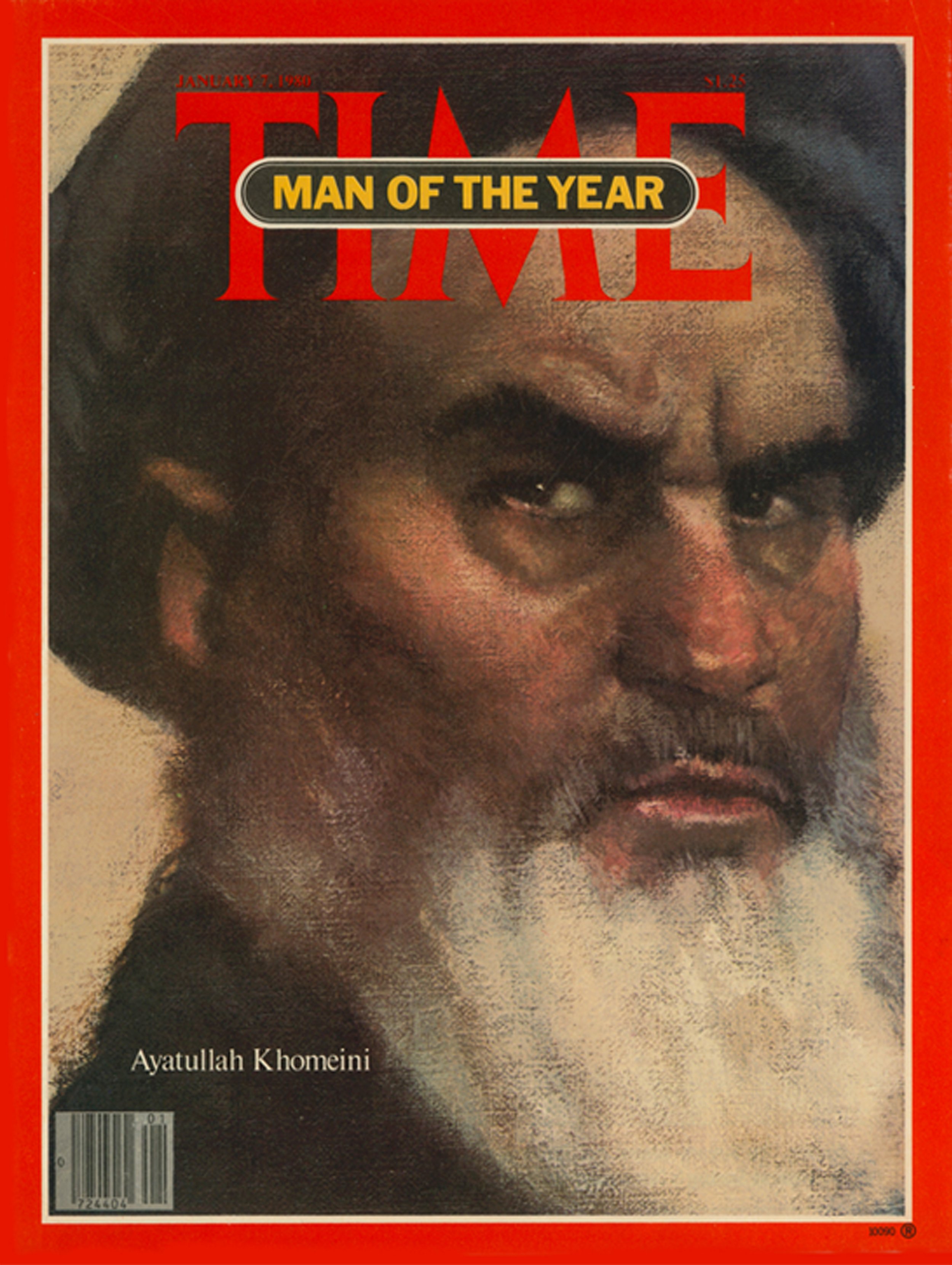

And that started her business. Those kinds of stories are deeply inspiring to me, and those women are deeply inspiring to me. Azar Nafisi, who wrote Reading Lolita in Tehran, just wrote an article for The Guardian about the protests that are going on in Tehran right now, actually all over Iran. And she was in Iran during the revolution that brought Khomeini into power. And Reading Lolita in Tehran tells that story. I was able to become friends with her and interview her at Civitella Ranieri, which is an artist residency program, and make a video with her. And to be able to meet somebody like that, who can really change your life because of their perception, and dedication, and belief in humanity, is a gift.

“It was too horrible to fire people who you loved, who you cared about, who were your friends, who you hired and trained yourself, and who were, I thought, geniuses.”

Patrick Mitchell: I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that you’re a trailblazer. One of six from a family in New Jersey. But you are a true icon for art directors, and for women. How do you think about your legacy?

Gael Towey: That’s a very good question. I don’t know how to answer that. I will say that for the women who are out there working now, remember to step back, and take stock, and appreciate where you are and what you’re experiencing, and remember those moments. Put them in your mind catalog. Because those experiences—it’s the process of the doing that really is the wonder of life, and living life, and having a career. That’s the great experience.

You know, I won a lot of awards. We won a lot of awards. That’s great. I don’t even remember what they were. Because that’s not the important thing. The important thing is having the experience of being able to have that creative life. So, I don’t know whether that’s a legacy or not. I do believe in women and their artwork and their inspirations, and I think that I could tell from one thing that, and I think Deb would agree with this, we got so many letters from people all over the country, thousands and thousands of letters. We reached more than a million letters at one point. And they were all so happy to have these ideas of how to bring creativity into their life.

And that was a real revelation for me. So when I left there in 2012, I thought, creativity is one of the most important things that we can give to people. Learning how to listen to yourself and listen for your own inspiration that’s inside you. That’s something that you can learn from artists.

And that’s what I mean when I say artists are brave. They’re brave because they have the openness to listen to themselves and to keep plugging away when it’s not working and keep doing the work over and over again with that kind of discipline. We have so much to learn from all of those people.

So, if my Portraits can help people be creative, then I feel that I’ve done something.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I can speak for all the dudes out there too. You were super inspirational to men as well, especially in our profession. So thank you for that.

Debra Bishop: And I do think that the work that you’ve created throughout your career is a huge inspiration to women, Gael. That is a very big legacy.

Gael Towey: Thank you honey.

Patrick Mitchell: We’re going to ask the million dollar question.

Gael Towey: Okay.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so Laurene Powell Jobs calls you. Says she’s got a blank check for you.

The only requirement is that you use it to create and launch a print magazine. Money is no object. What will you make?

Gael Towey: I would make something that would bring all of my friends together and would allow me to work with the extraordinary people and talent that I care a lot about. I think I would do a magazine about making— about making art and all kinds of art and focus it on the process of making, and the process of the creative life, and how to live a creative life.

Debra Bishop: Wonderful.

Patrick Mitchell: Perfect. It’s okay if you have a circulation of 162.

Gael Towey: Yes.

Portraits in Creativity: Alabama Chanin

For more information on Gael Towey, and to see her Portraits in Creativity film series, visit her website.

Back to the Interviews

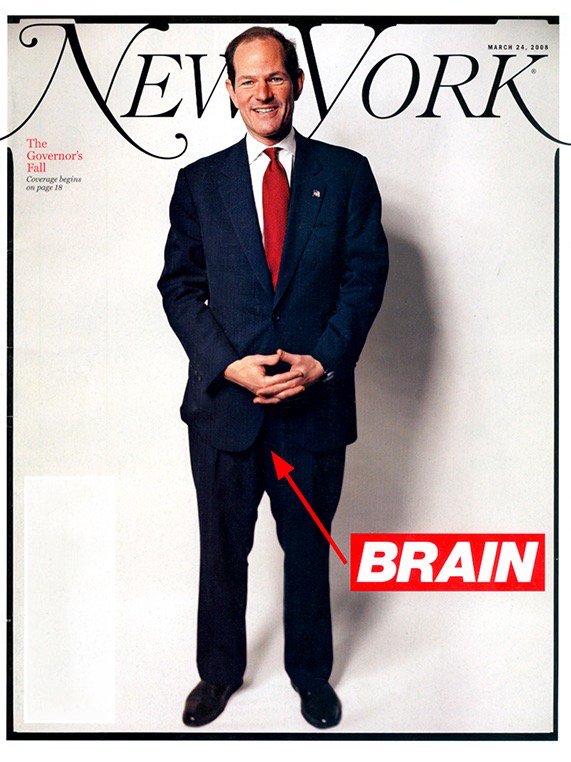

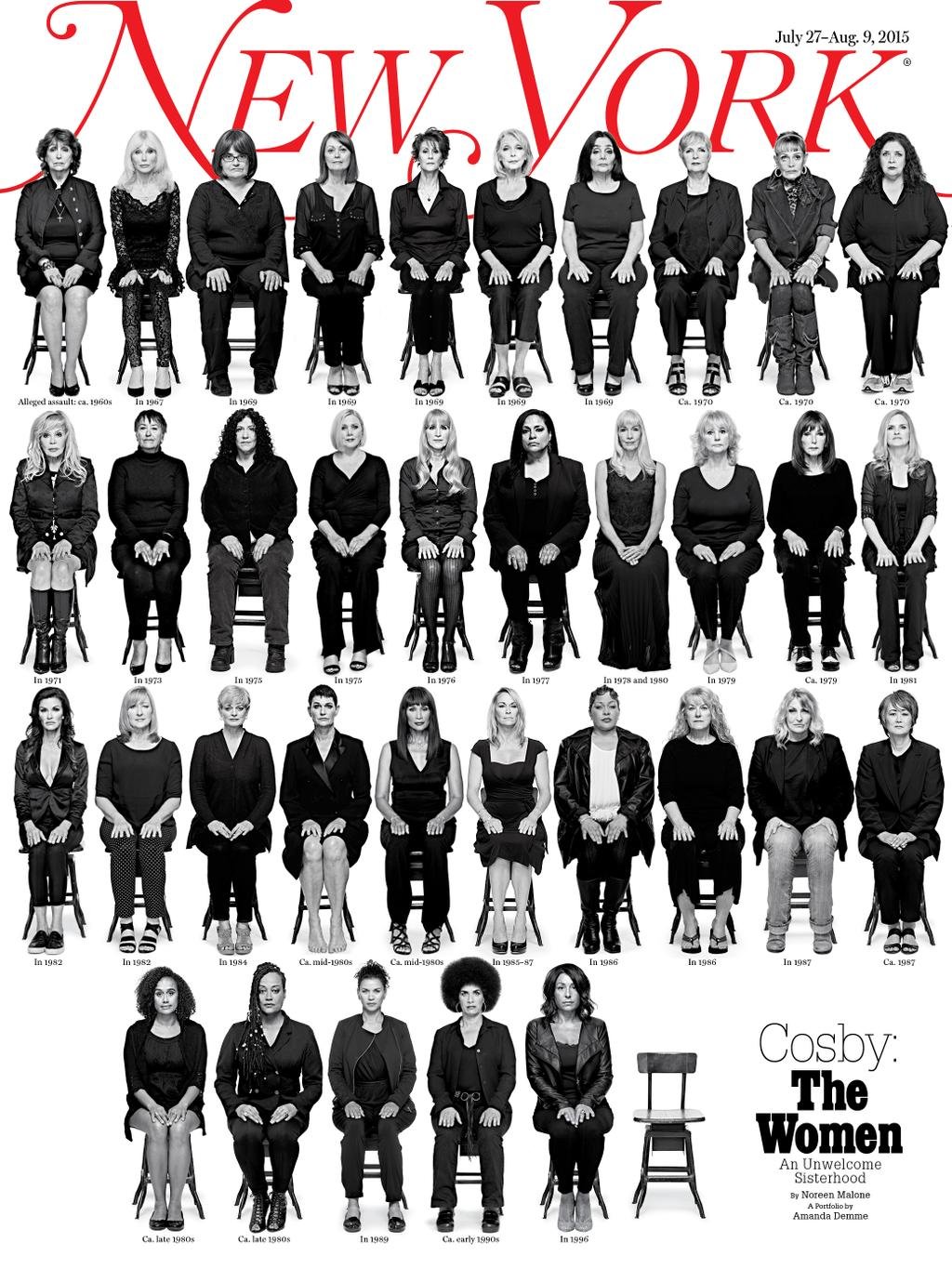

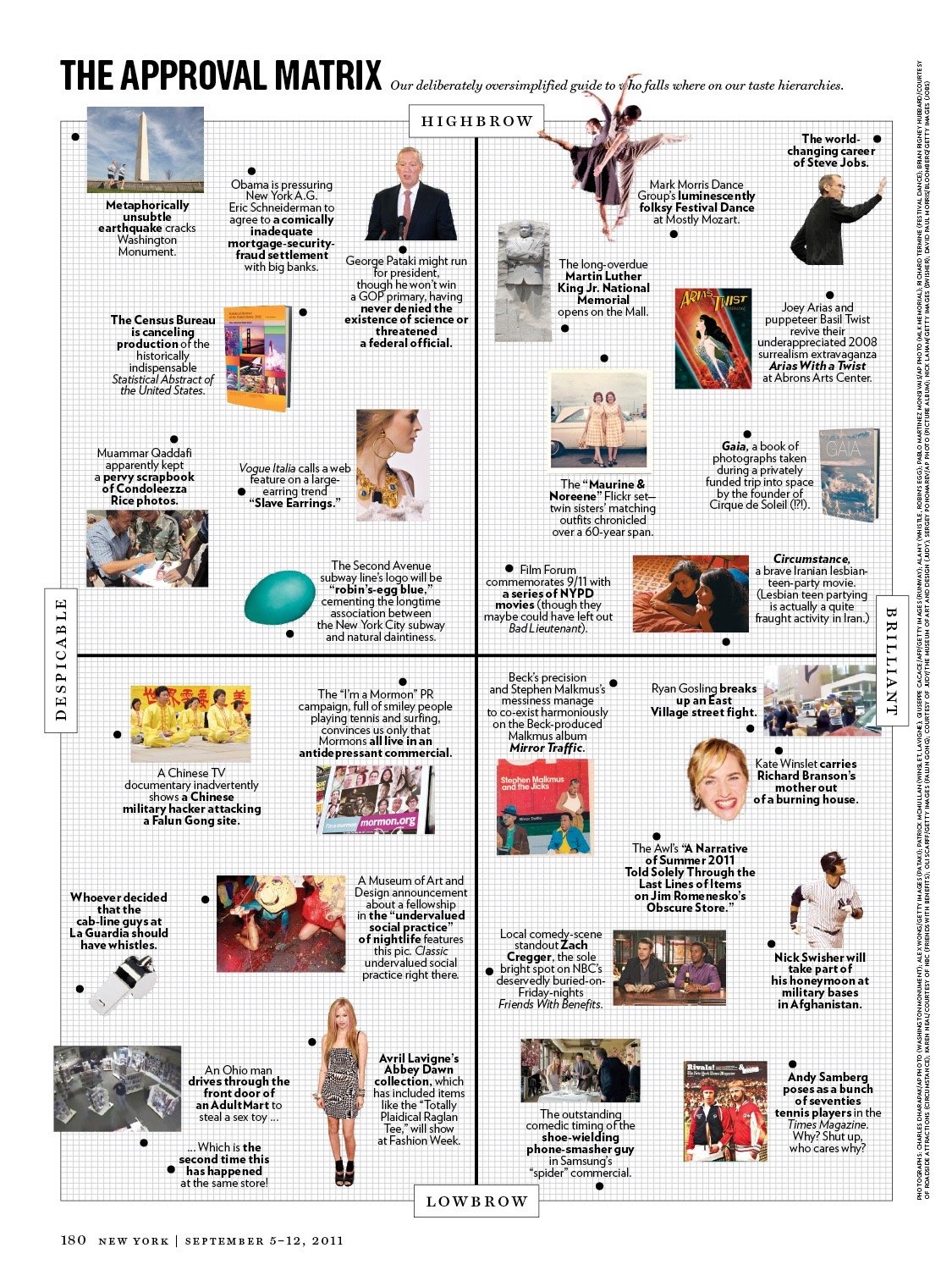

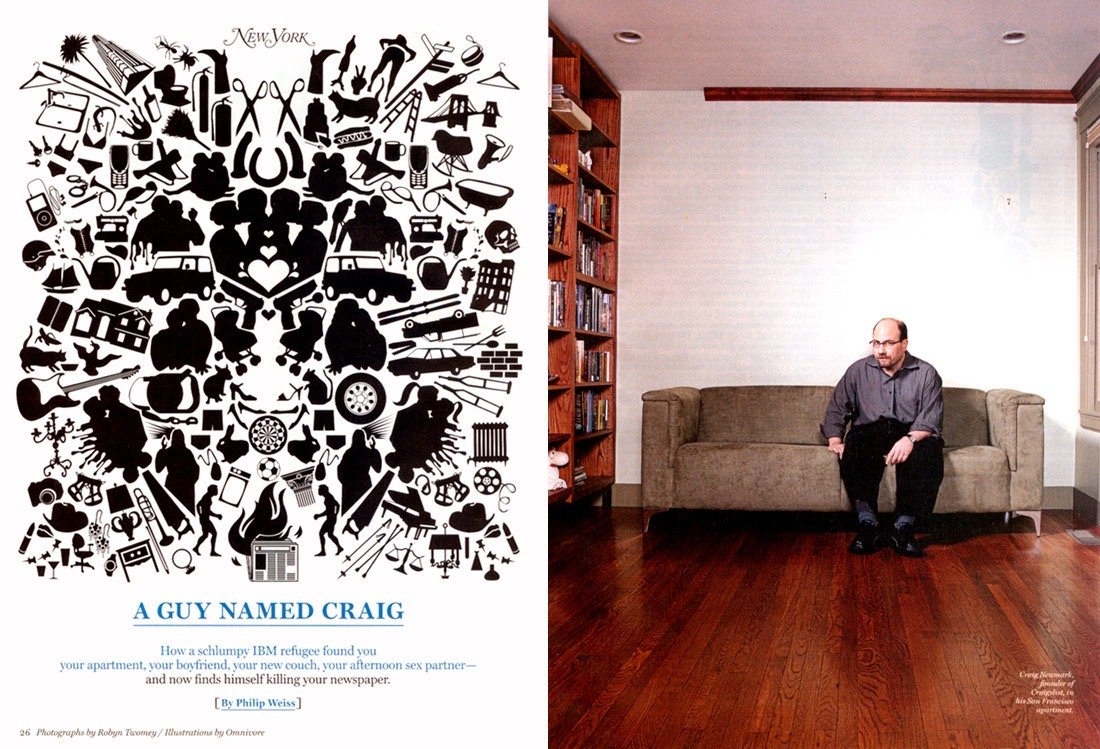

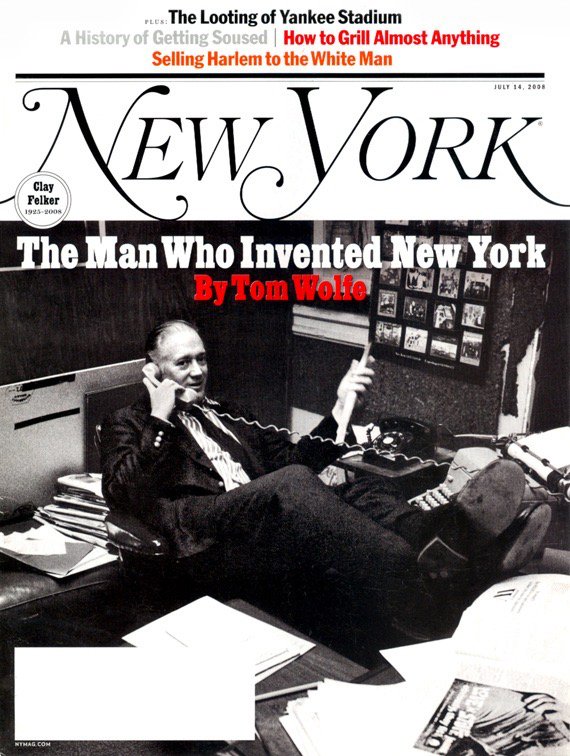

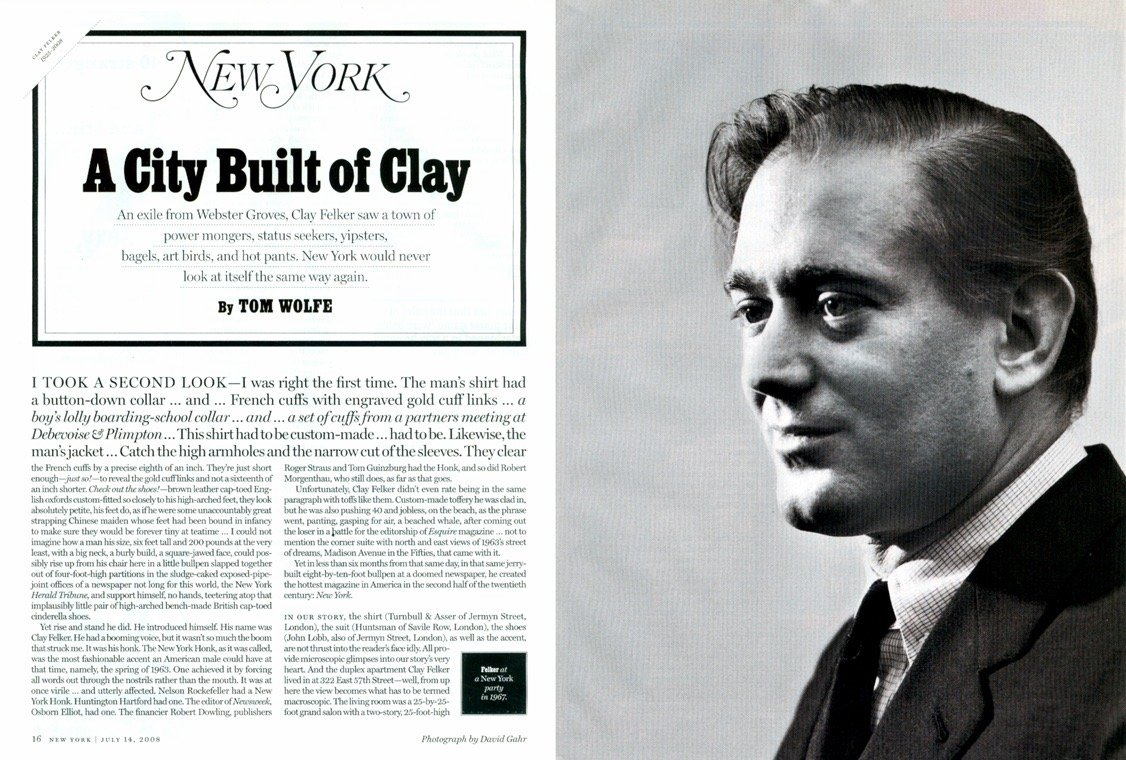

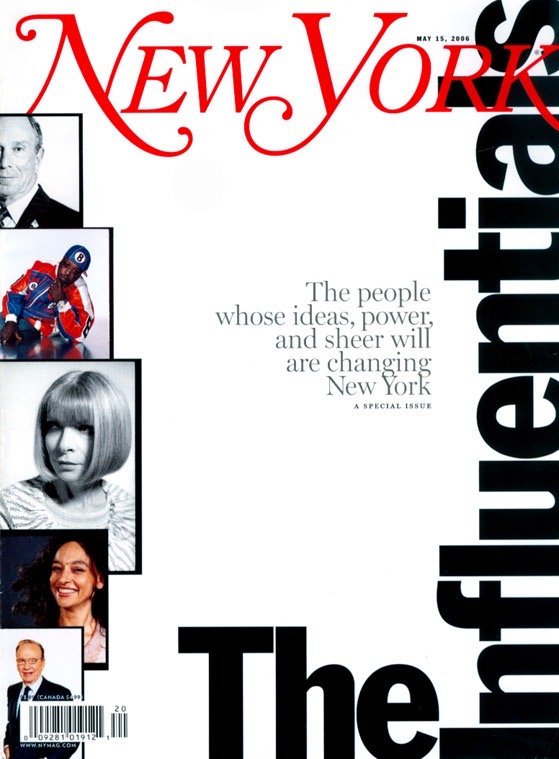

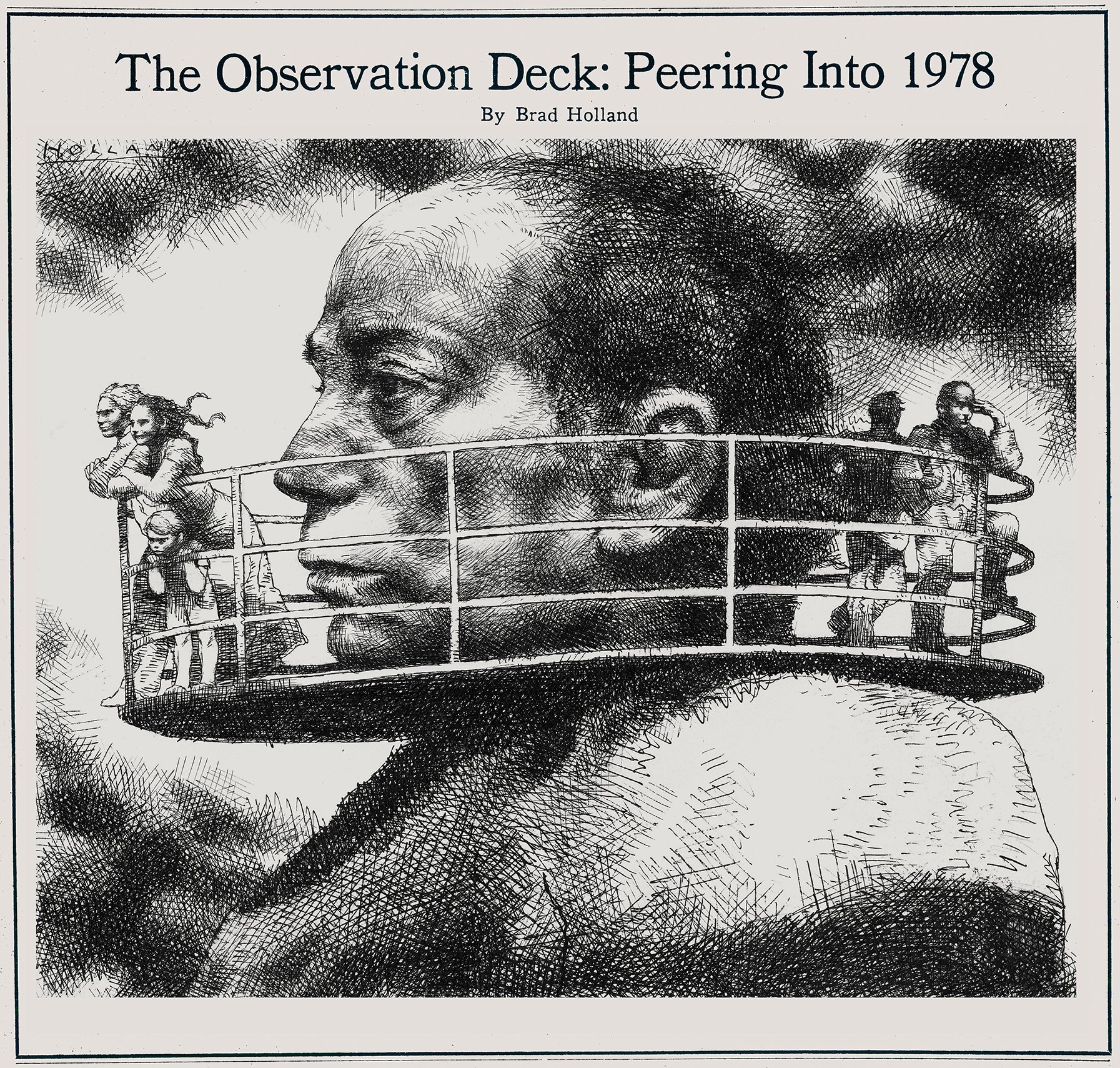

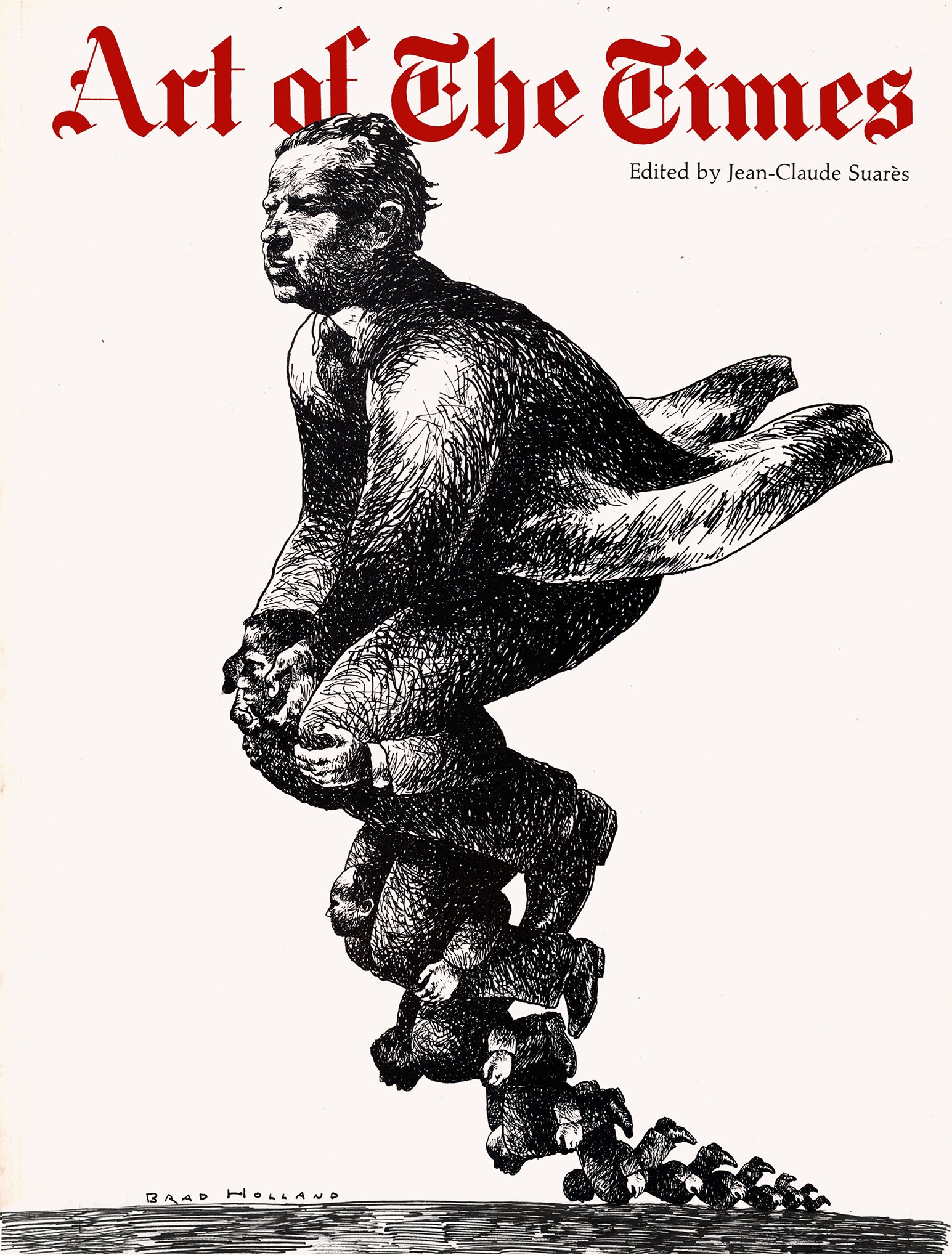

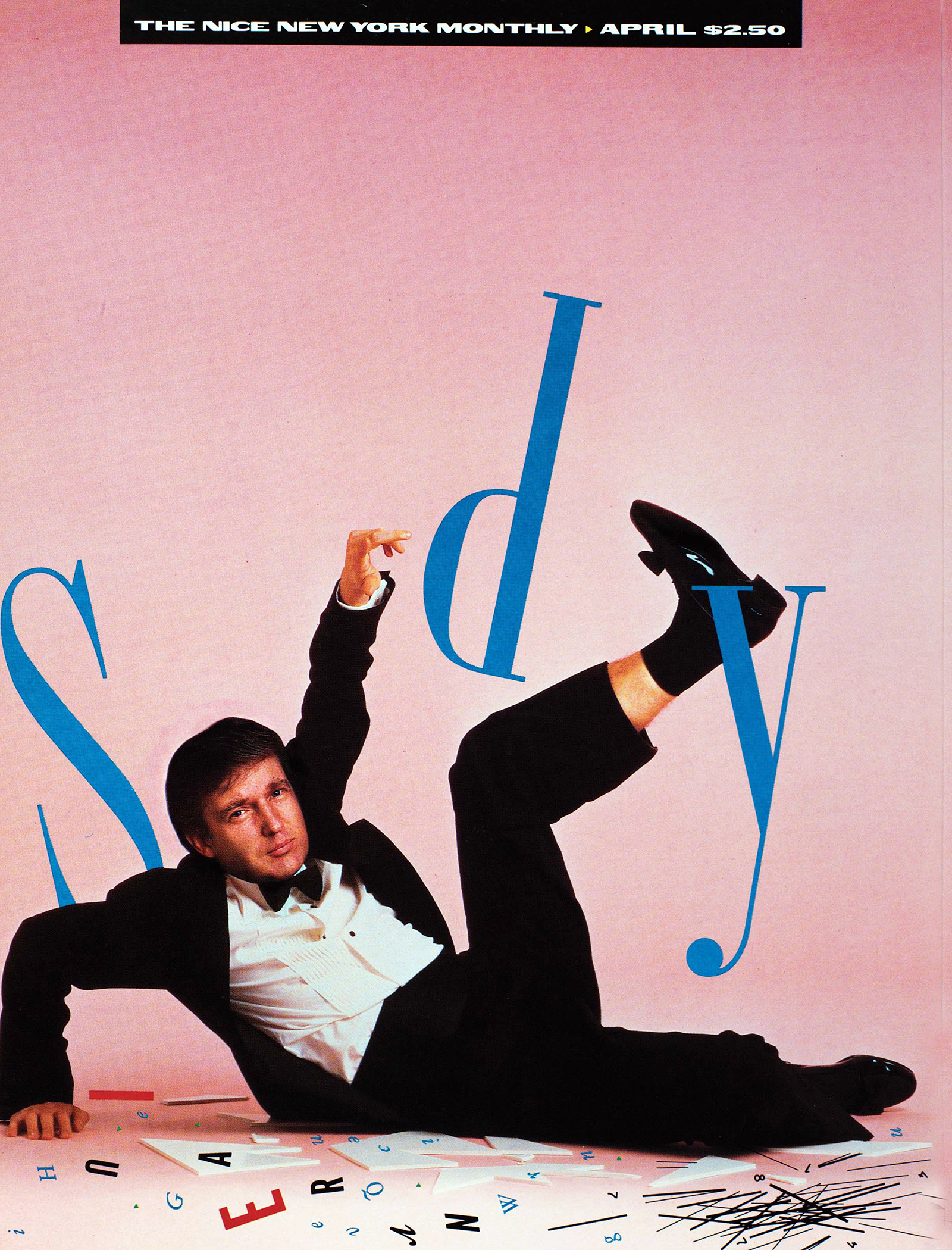

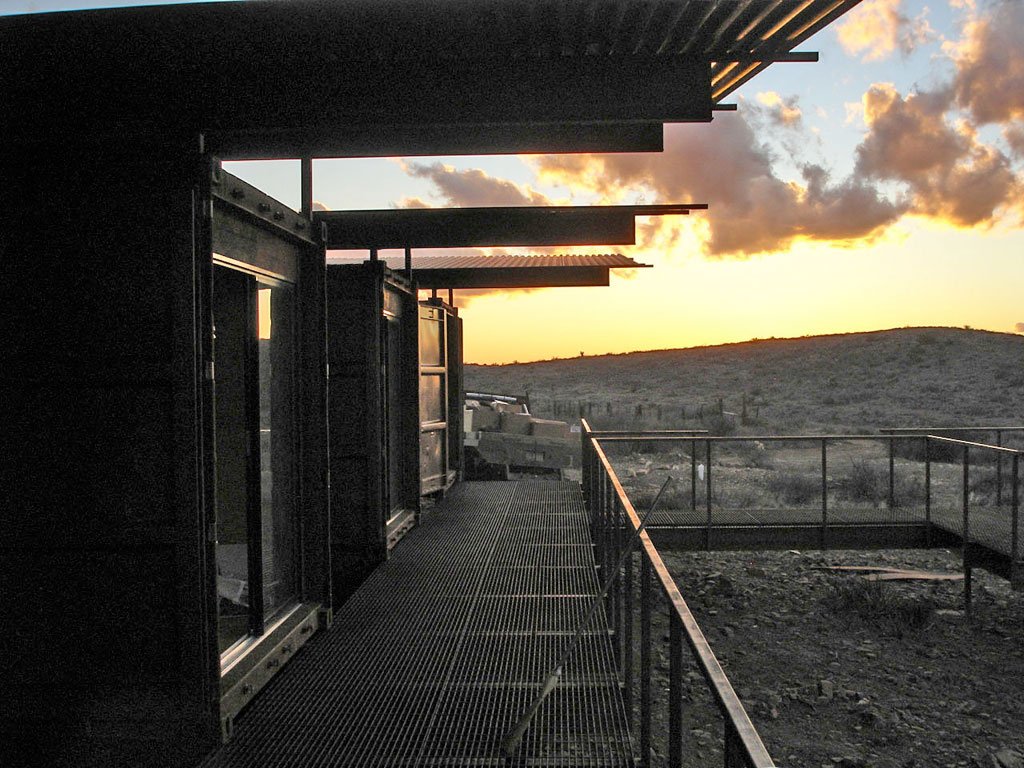

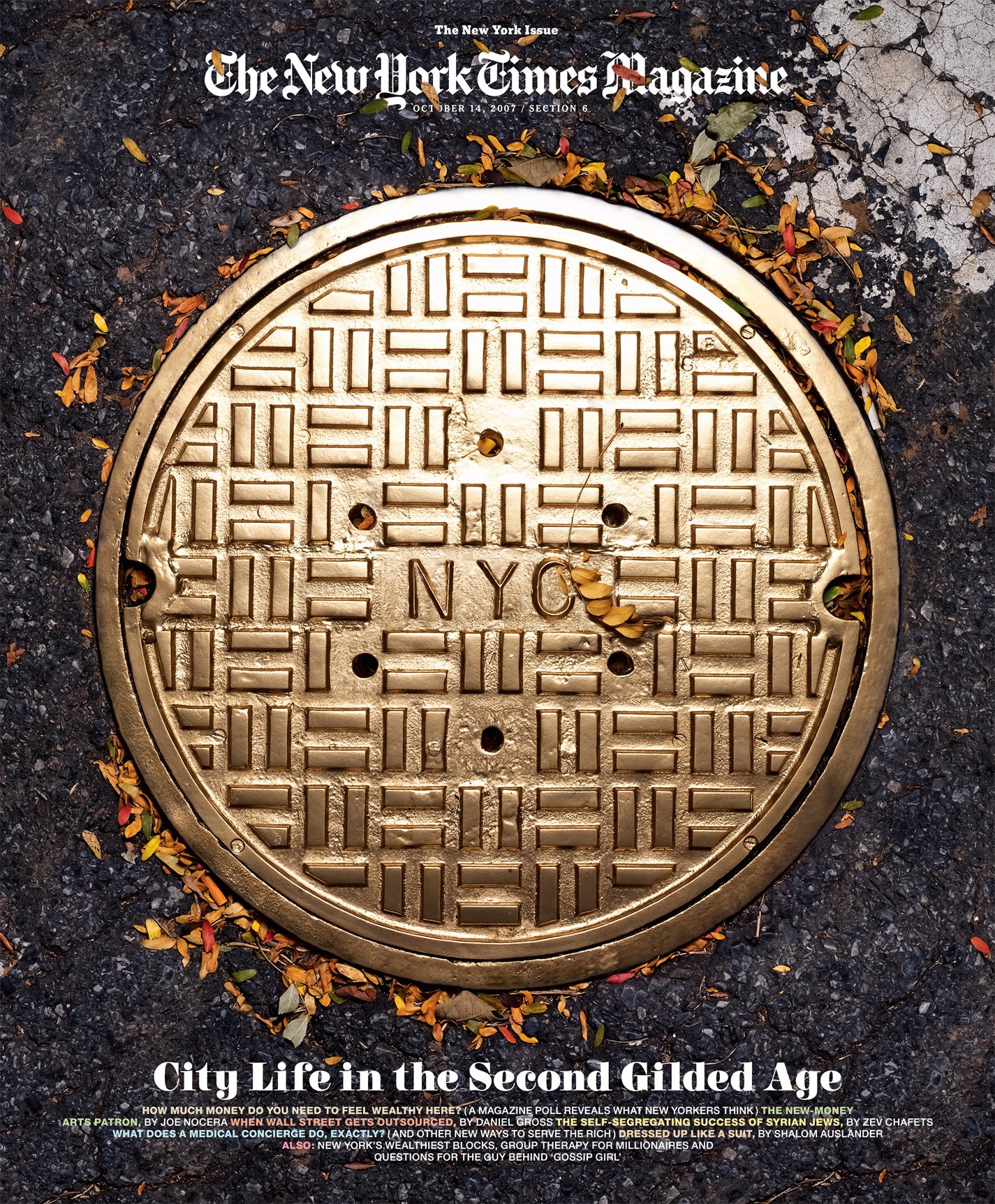

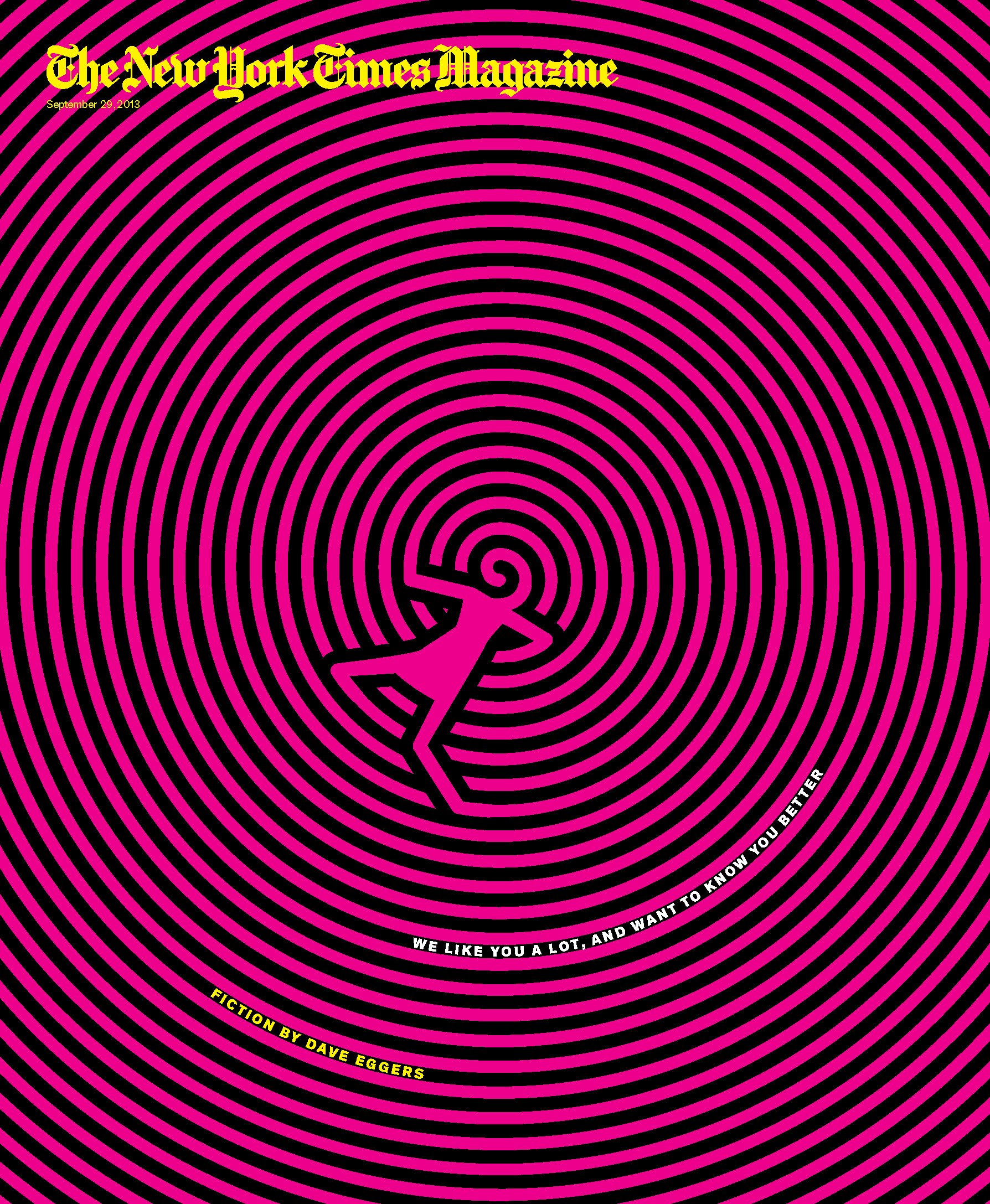

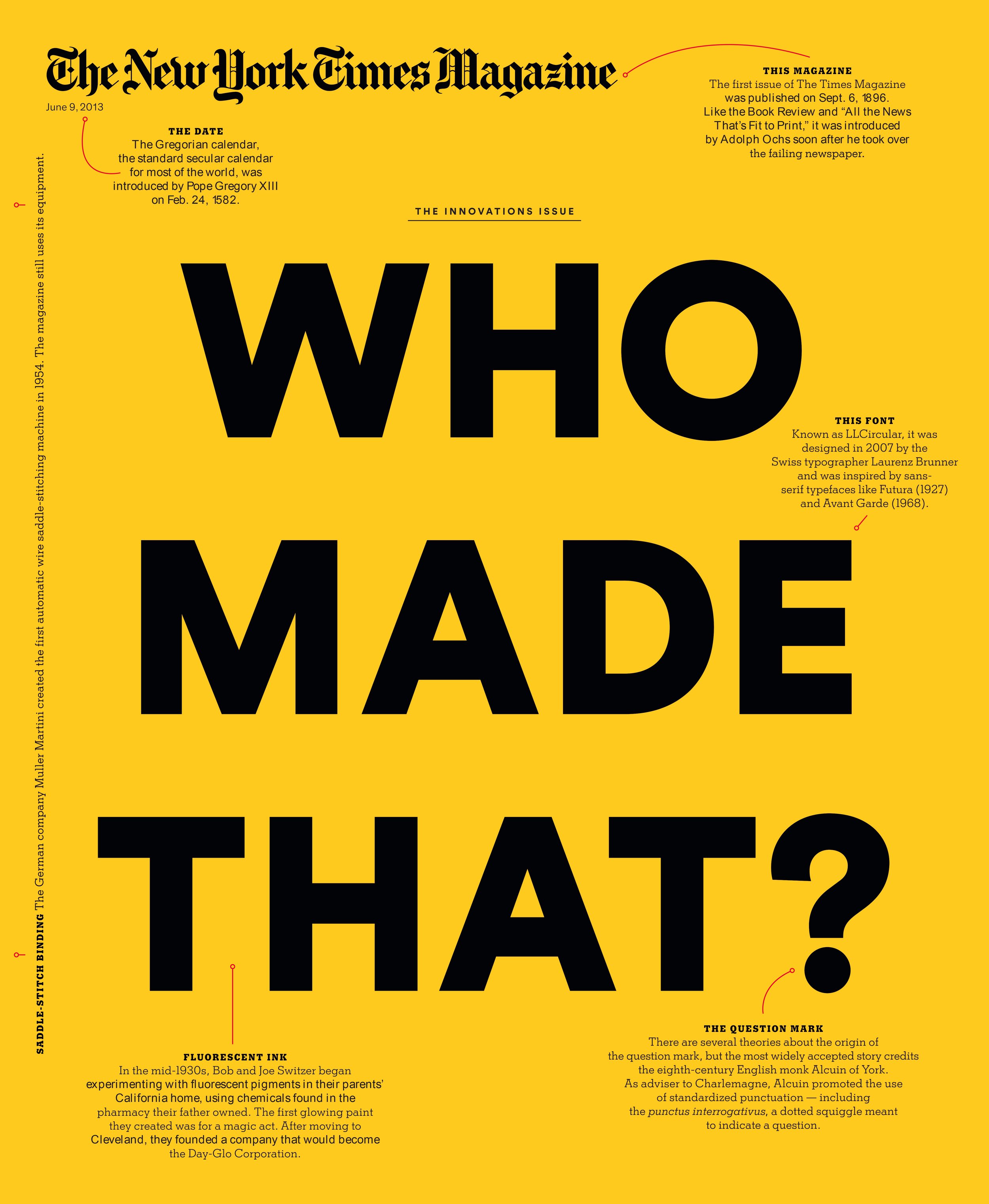

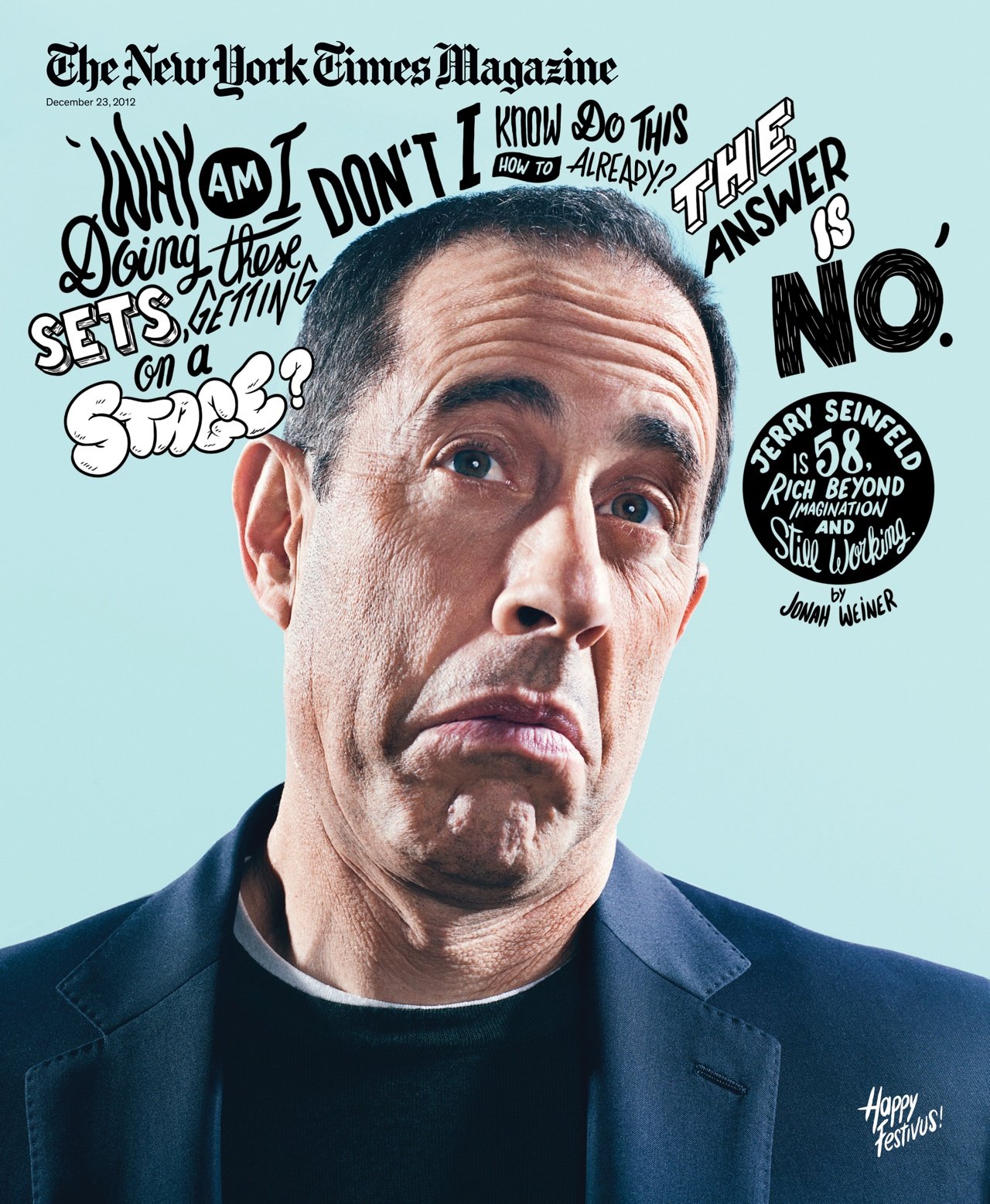

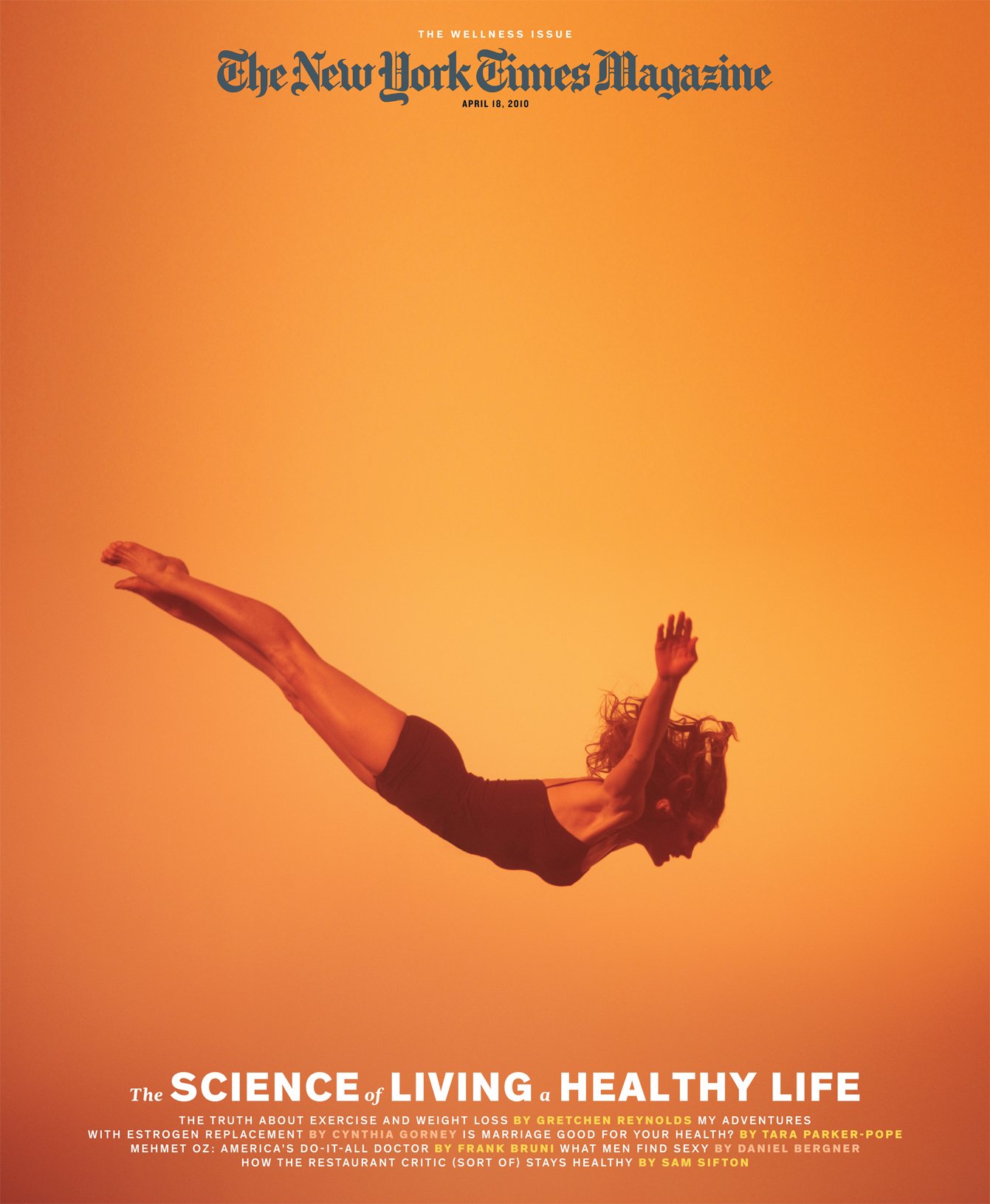

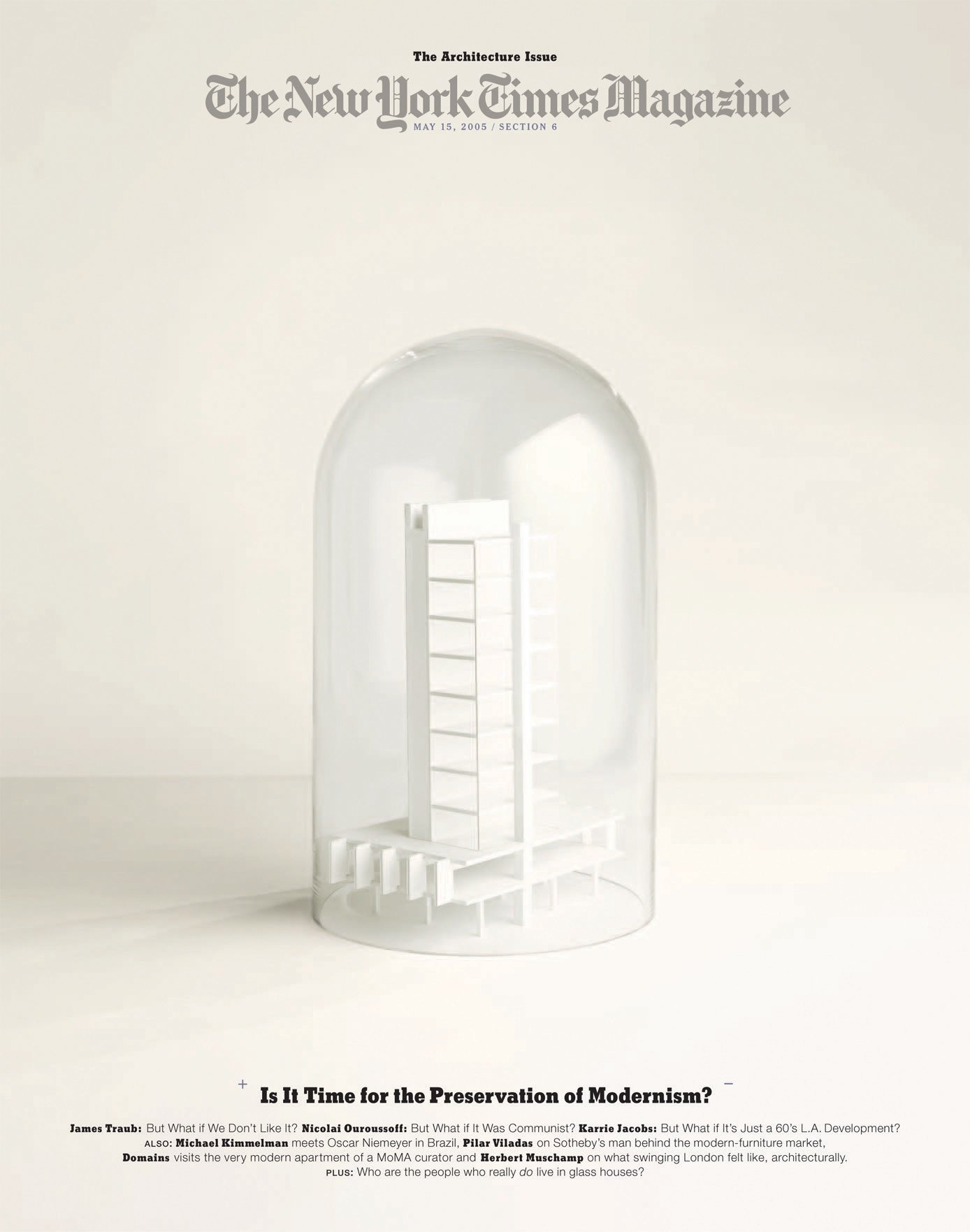

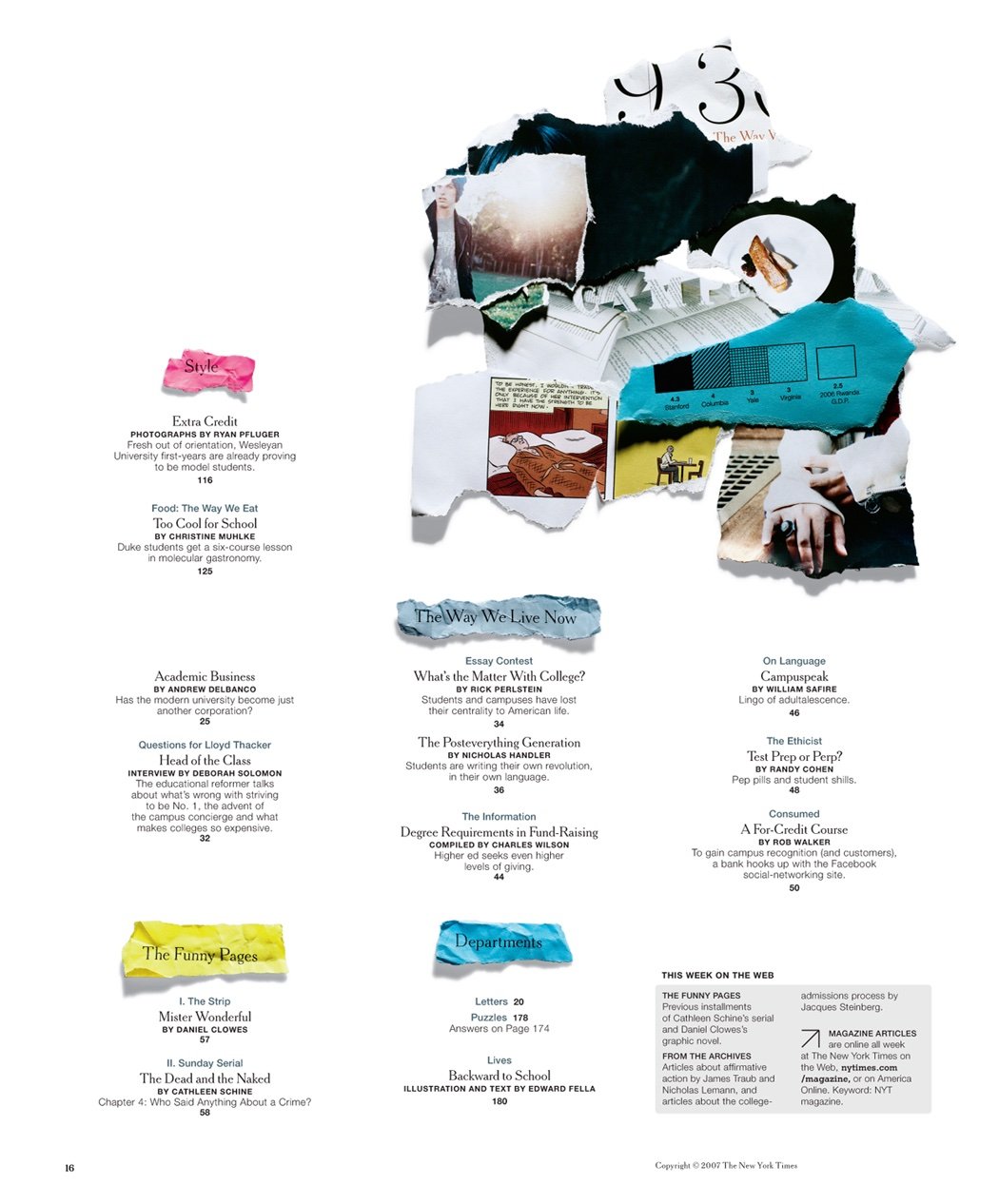

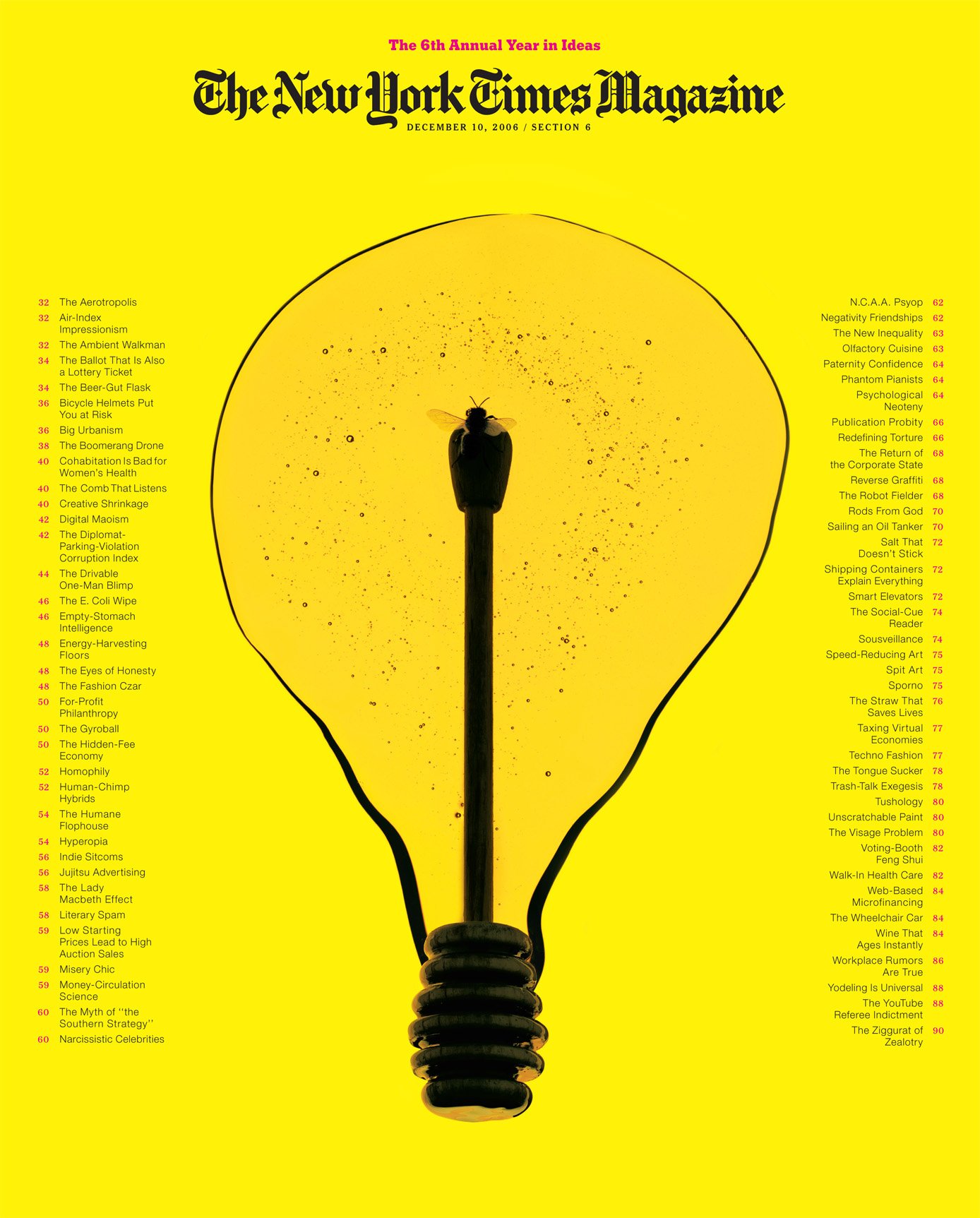

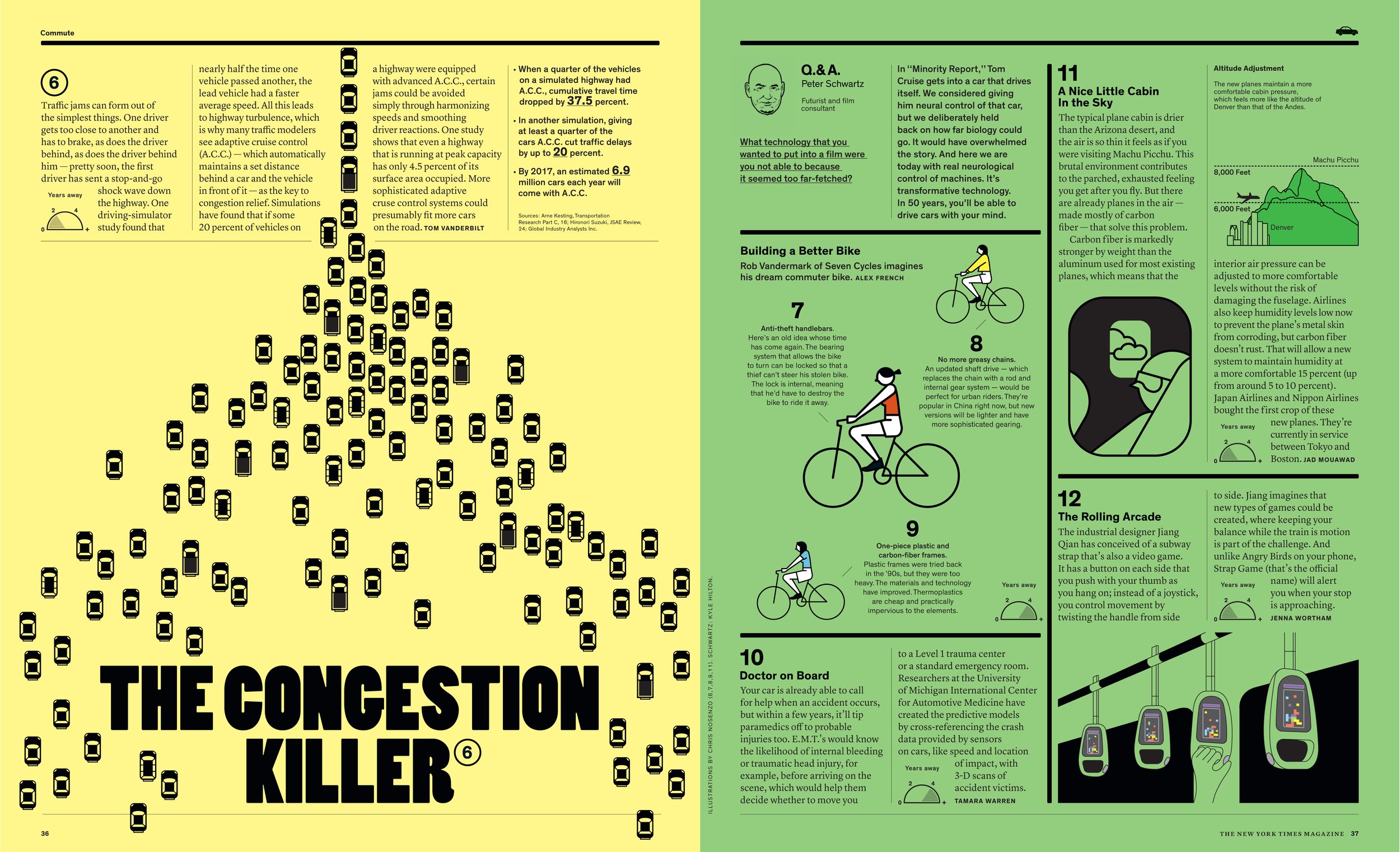

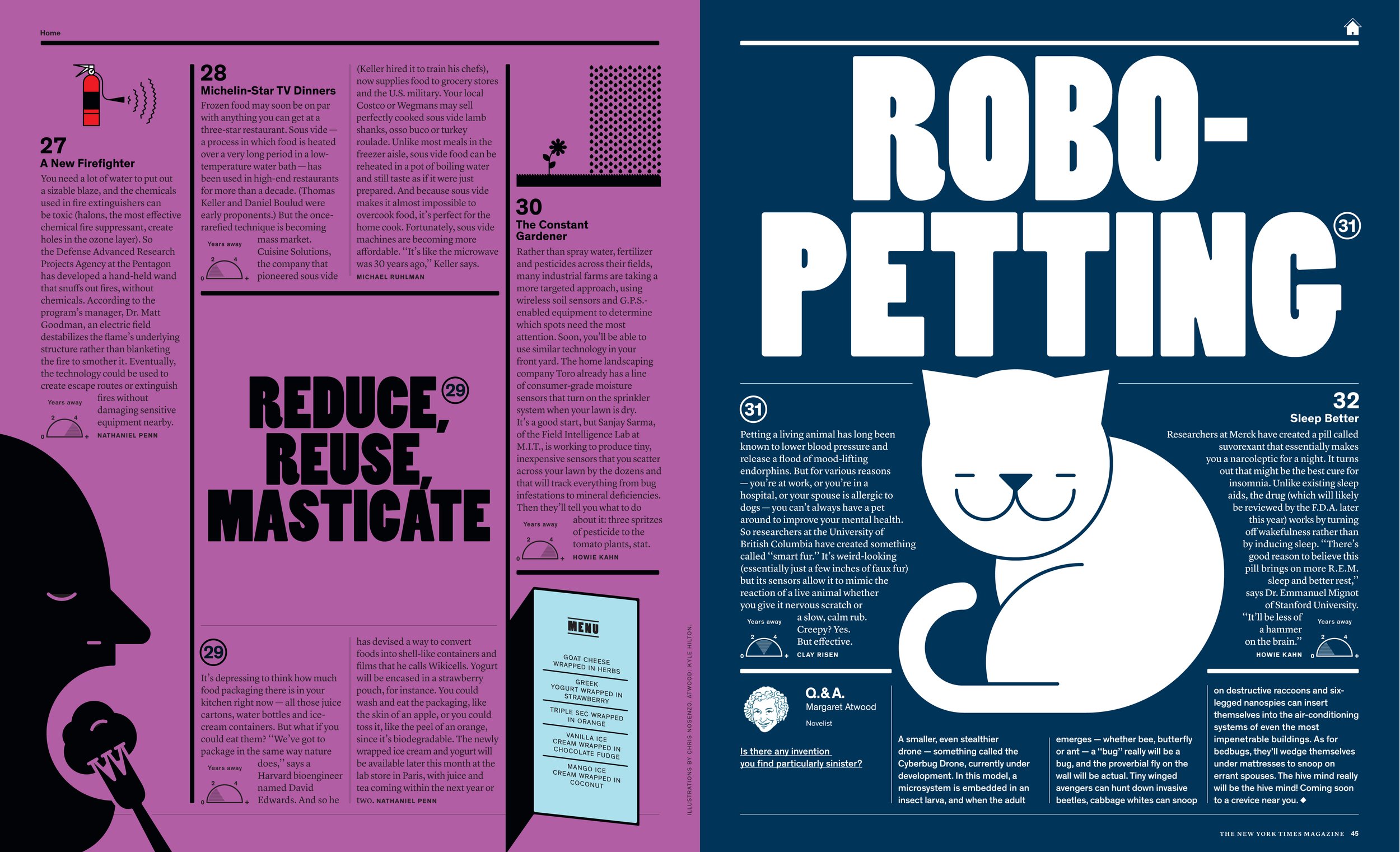

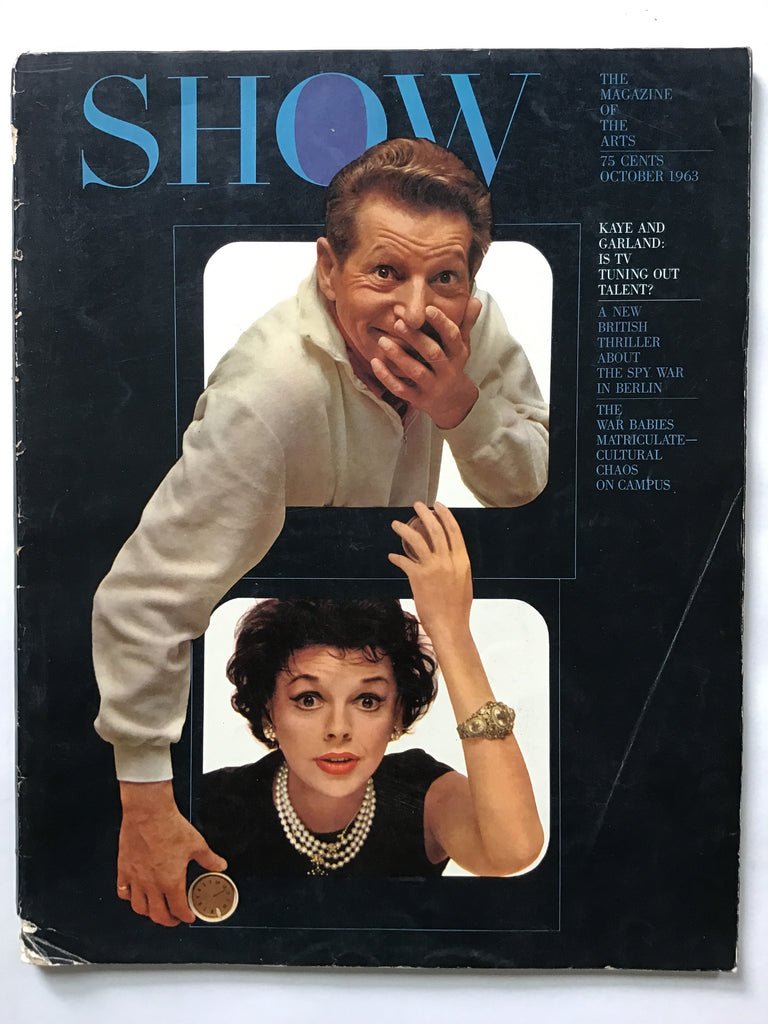

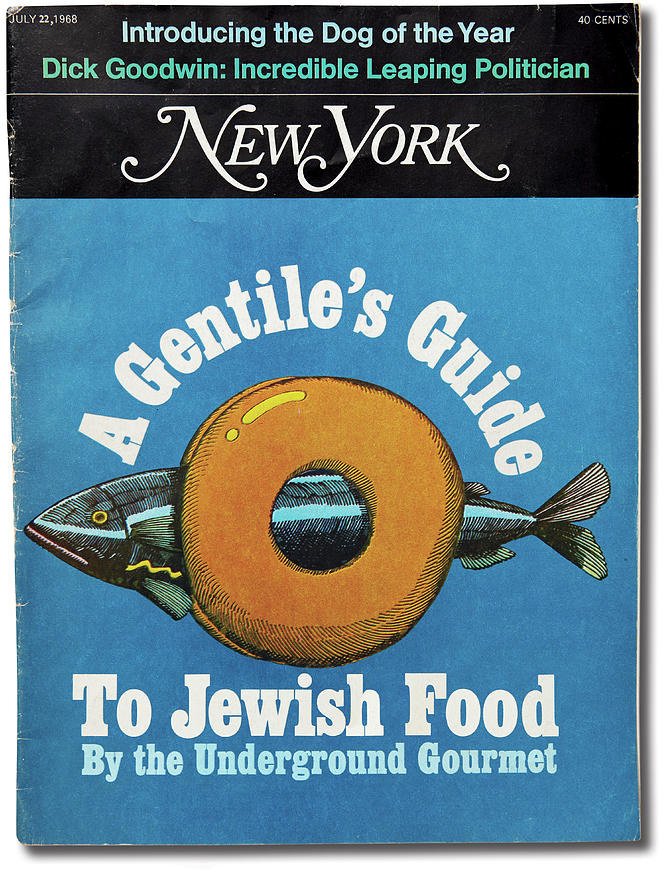

The Approval Matrix: Highbrow, Brilliant

A conversation with editor Adam Moss (New York, The New York Times Magazine, 7 Days, more)

A conversation with editor Adam Moss (New York, The New York Times Magazine, 7 Days, more)

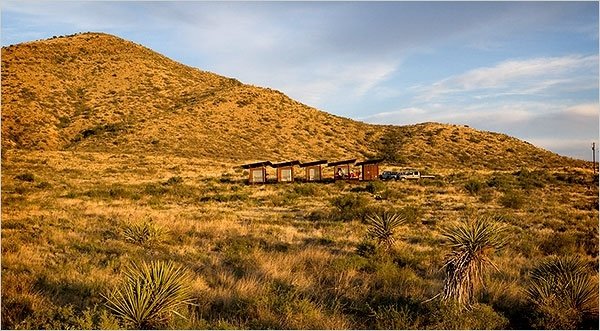

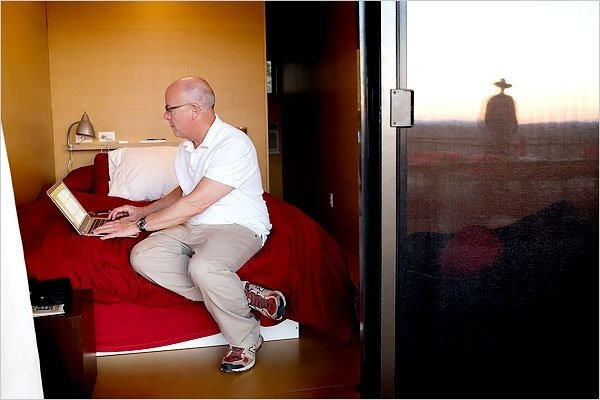

Adam Moss is probably painting today. He’s not ready to share it. He may never be ready to share it. You see, this ASME Hall of Famer unabashedly labels himself as “tenth rate” with the brush. And he’s okay with that.

As Moss explains, it’s not about the painting. After decades of creating some of the world’s great magazines, he is throttling down. He’s working with canvas, paint, and brush — and reveling in the thrill of making something, finally, for an audience of one.

It hasn’t always been this way for Moss. Like most accomplished editors — like most serious creatives — Moss spent the better part of his career obsessed. Obsession is essential, he says, to the making of something great.

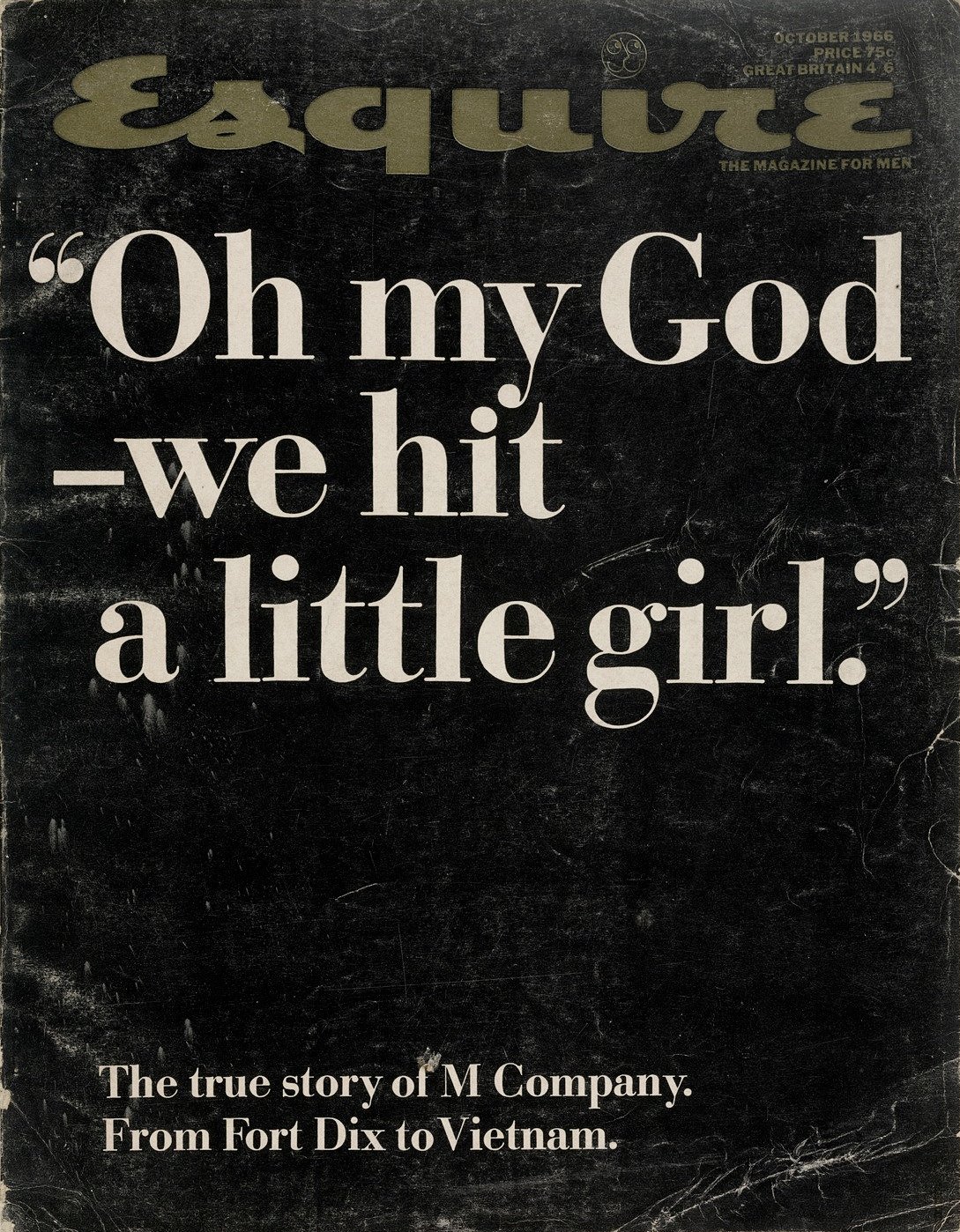

Growing up on Long Island, Moss became obsessed with Esquire and New York magazines. “My parents were subscribers,” he says. “I was in the suburbs. I’d open them and it was my invitation to New York City. And to cosmopolitan life. And to sophistication.” And knowing that it was all happening just a short subway ride away made it irresistible.

Moss’s publishing portfolio is rotten with blue-blood brands: Rolling Stone, Esquire, The New York Times, and New York magazine. He’s collaborated with editorial legends.

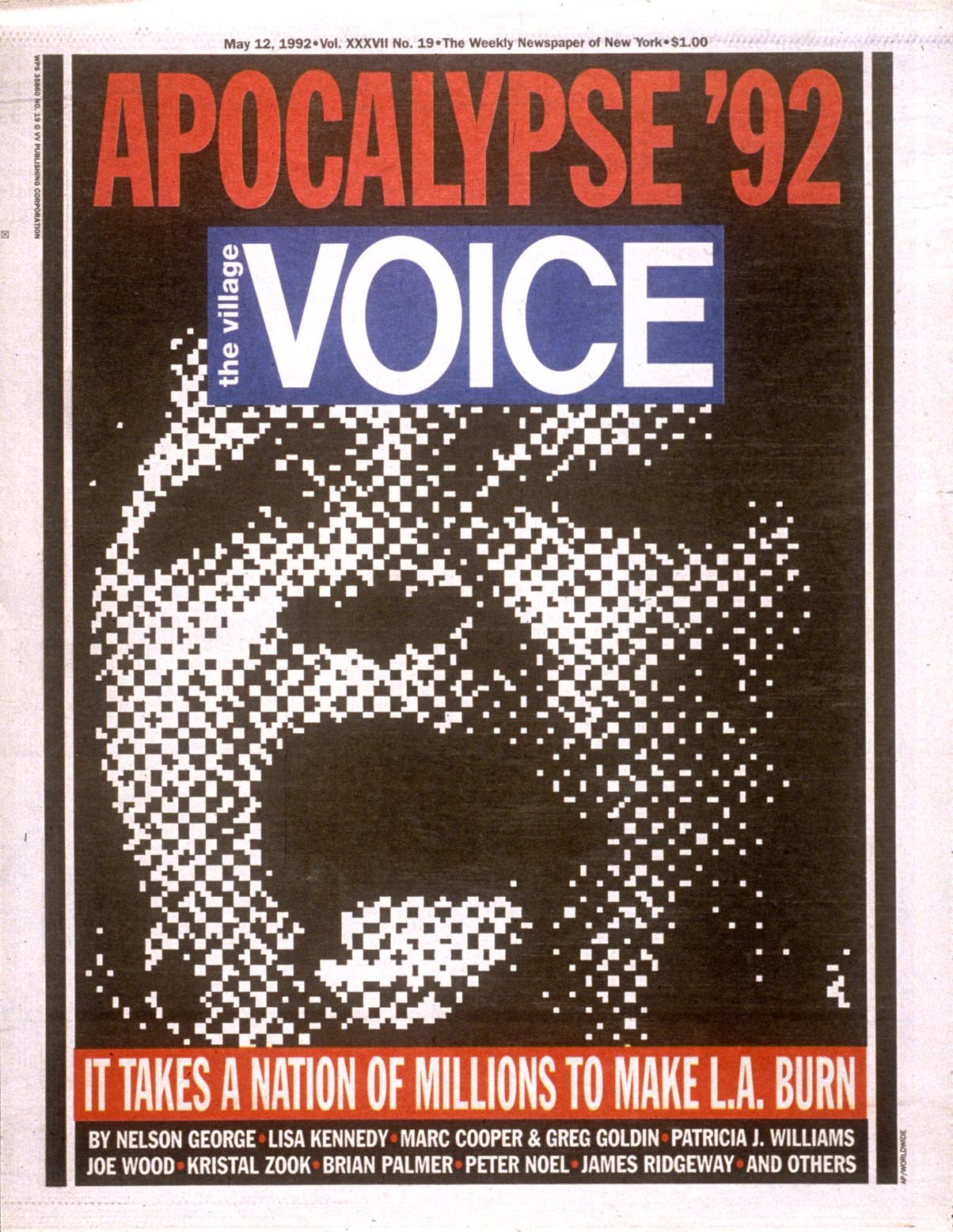

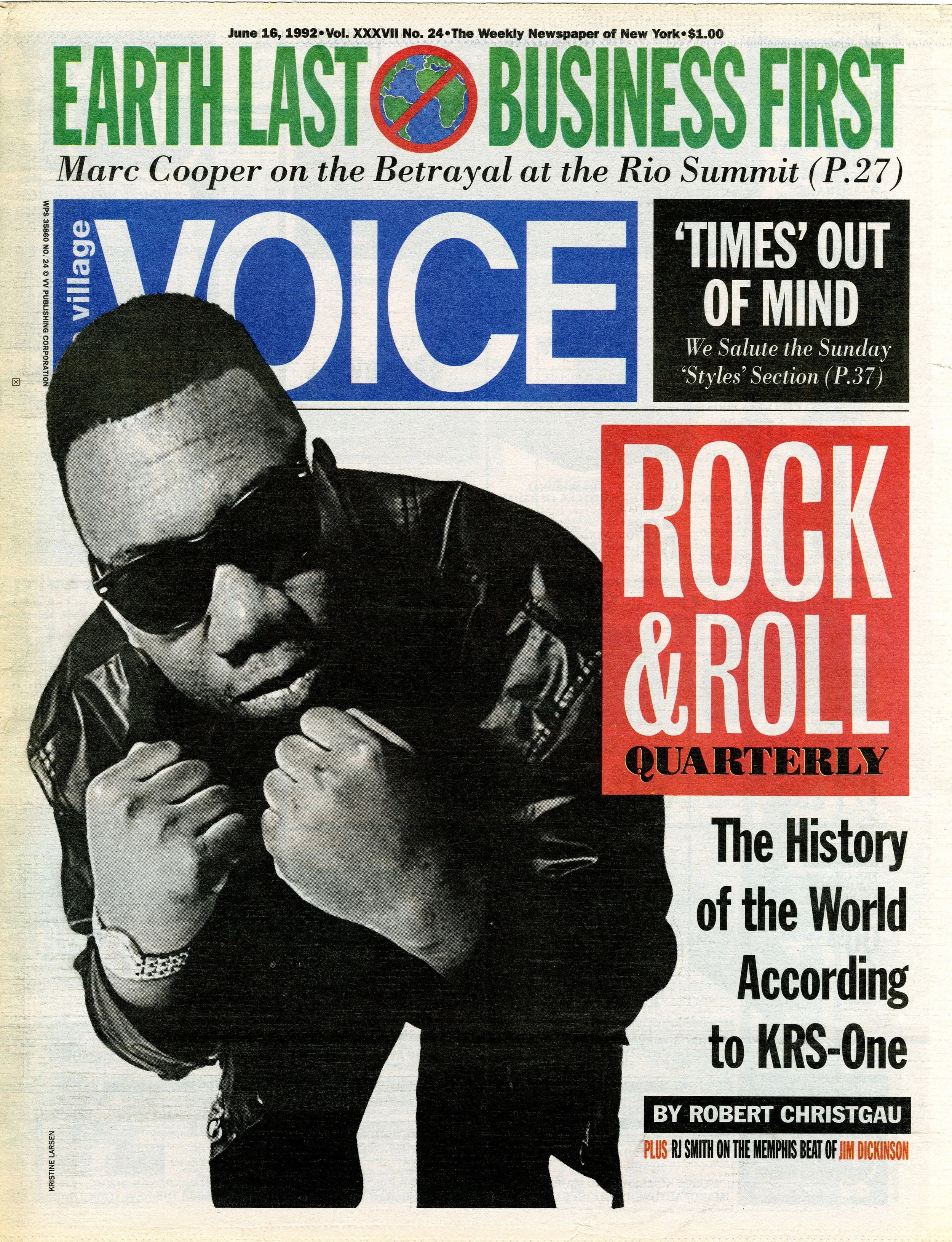

In 1987 Moss decided to create something of his own. Invited to pitch an idea for a new magazine to the owners of The Village Voice, Moss did his song and dance. The folks in the boardroom were … unmoved. Afterwards, Moss retreated to the men’s room to ponder his humiliation. Minutes later, Leonard Stern, the Voice’s owner, took a spot at the next urinal, where he turned to Moss and said, “Okay, we’ll do your magazine.”

What Moss pitched was a city magazine called 7 Days. It only lasted two years. But two weeks after ceasing publication, 7 Days was presented the National Magazine Award for general excellence.

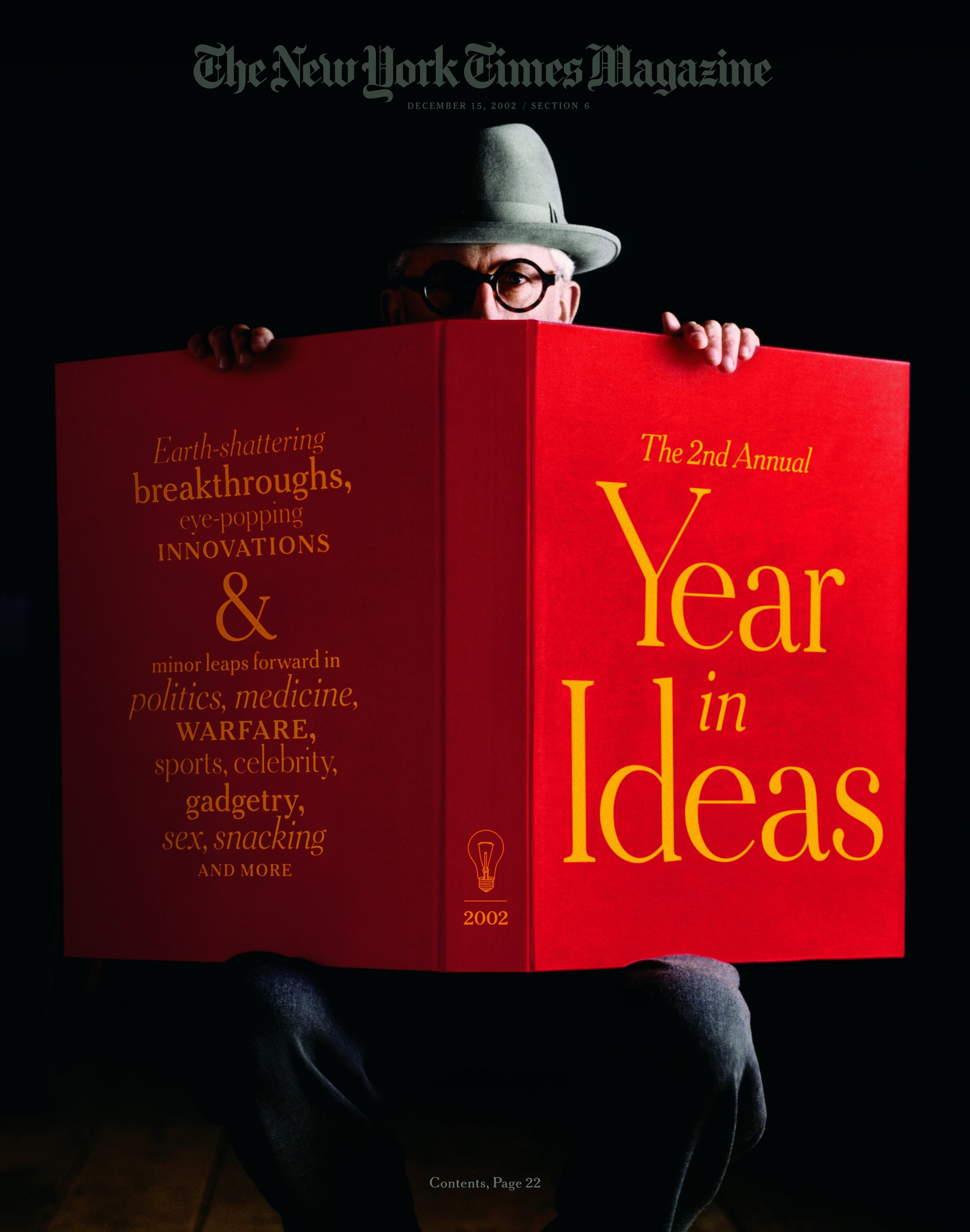

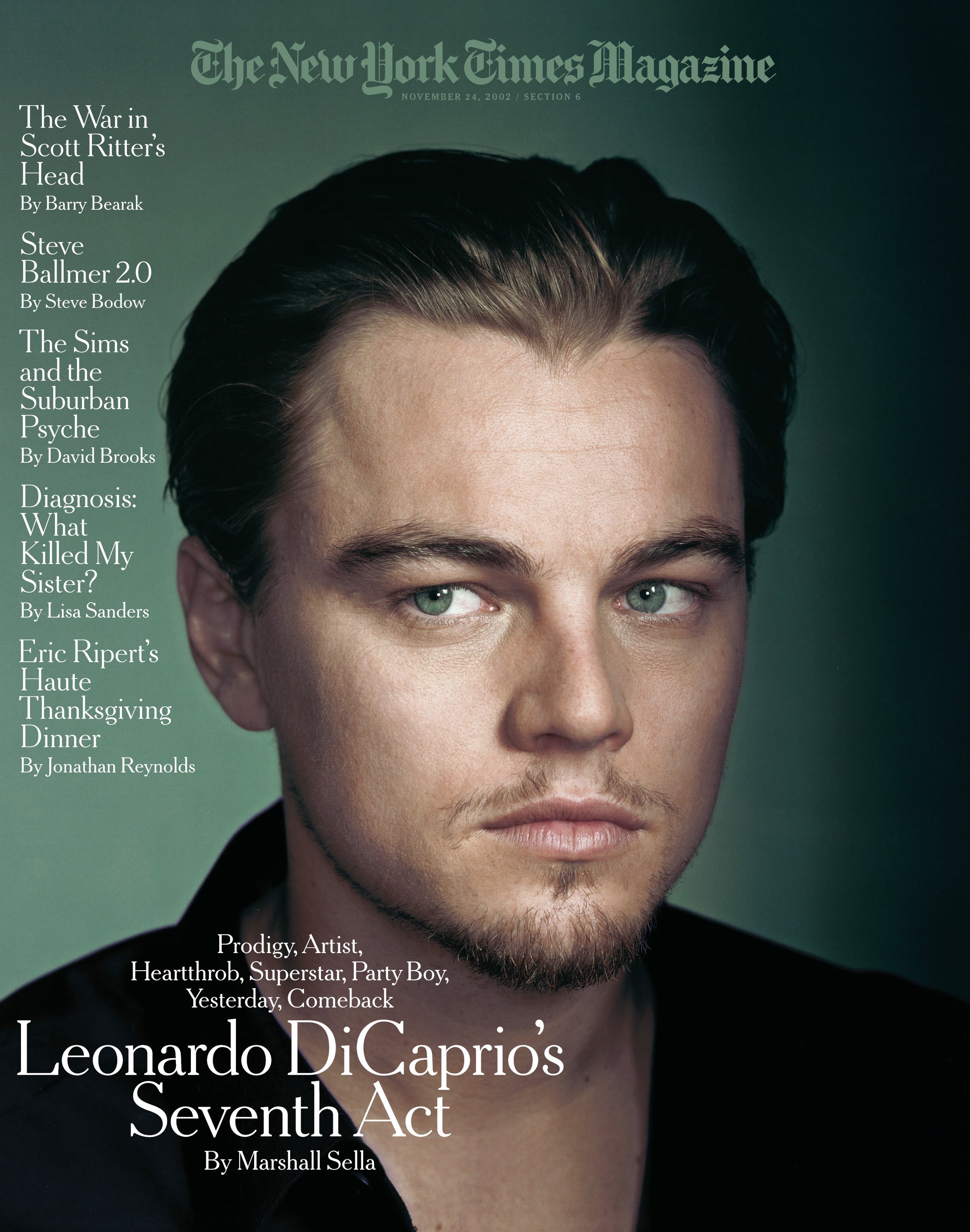

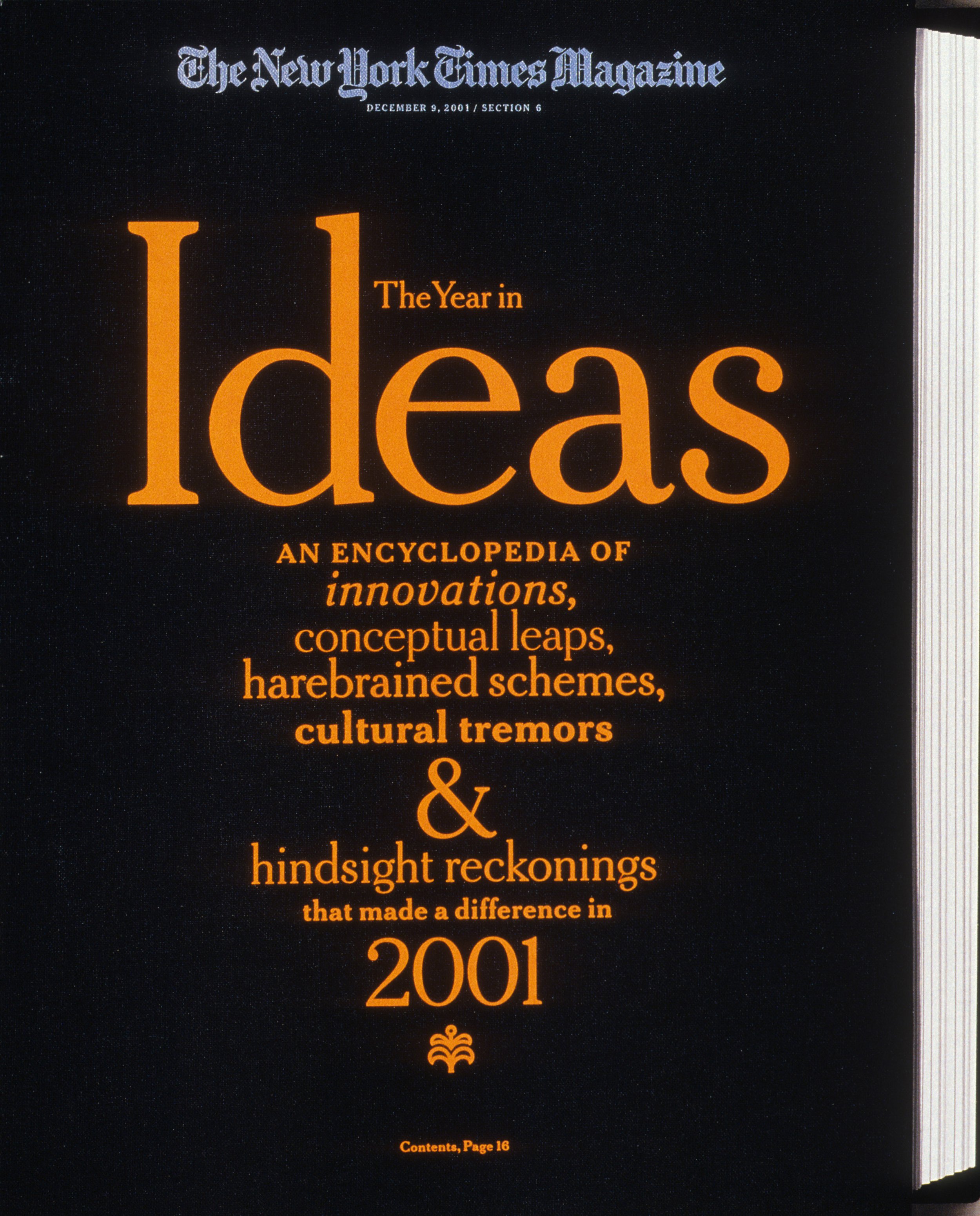

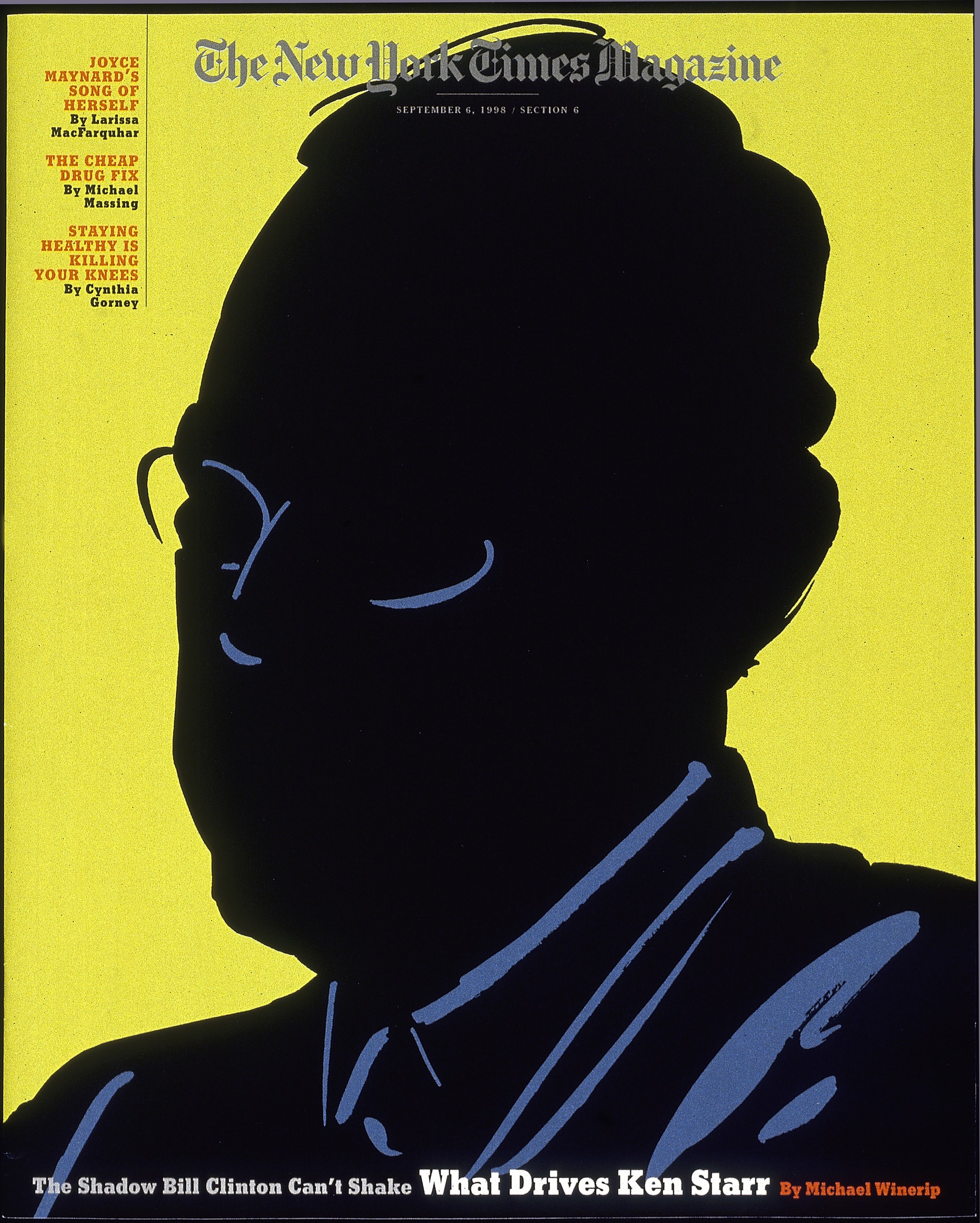

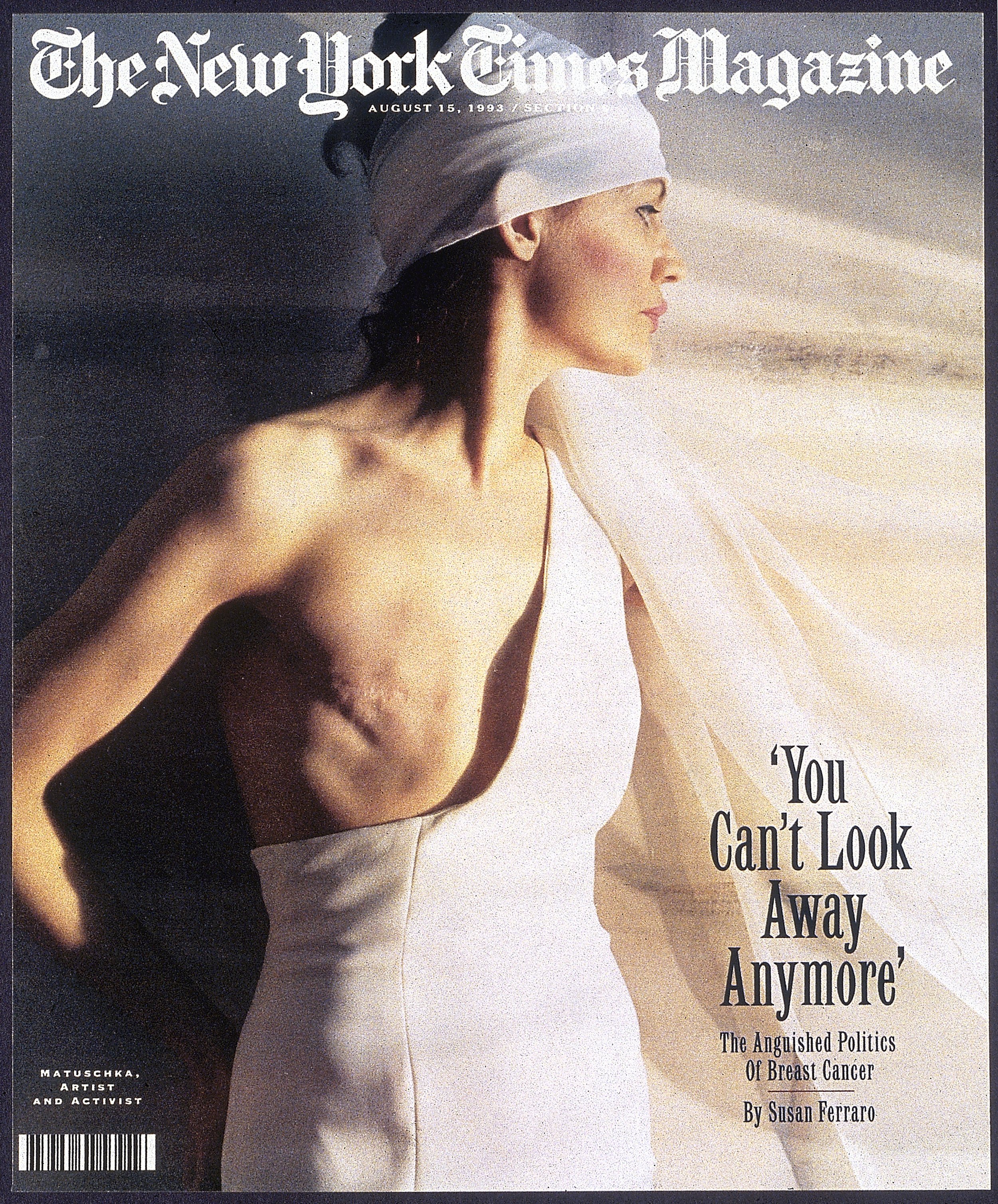

The splash it created propelled Moss to The New York Times, where, in a few short years, he transformed the paper’s Sunday supplement into an editorial juggernaut for creative talent — the Esquire or New York magazine of the 1990s.

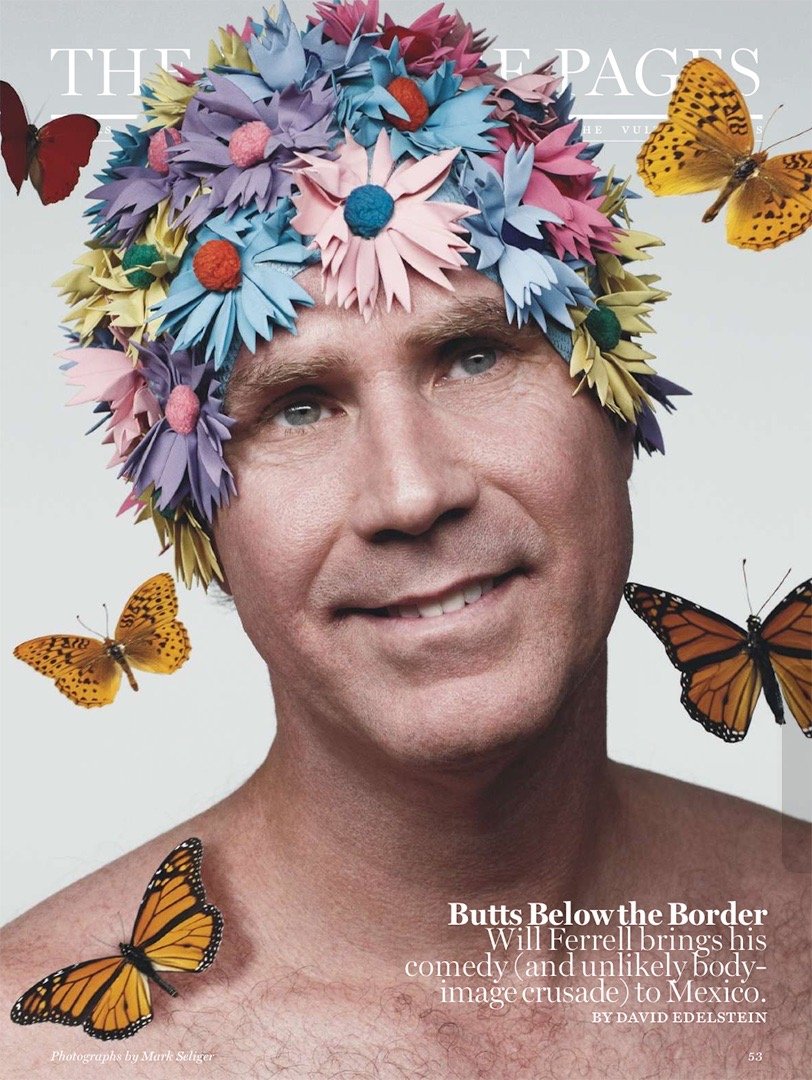

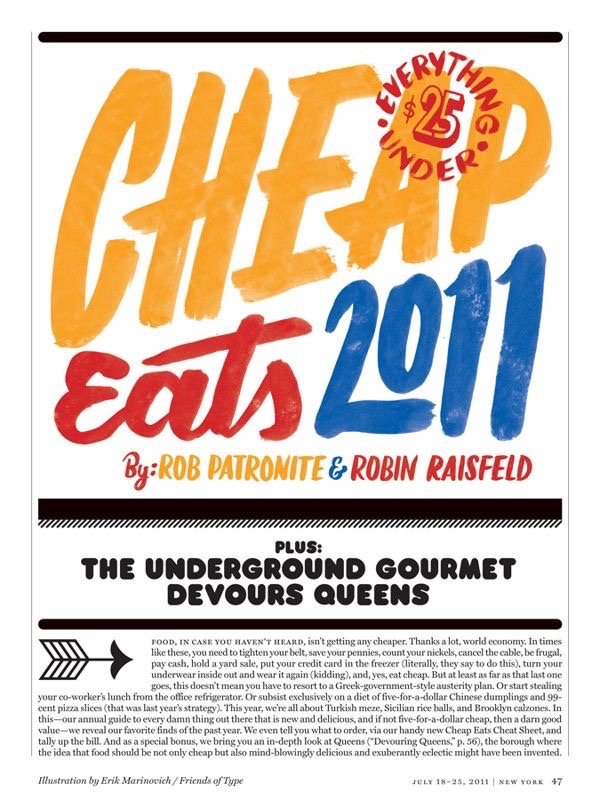

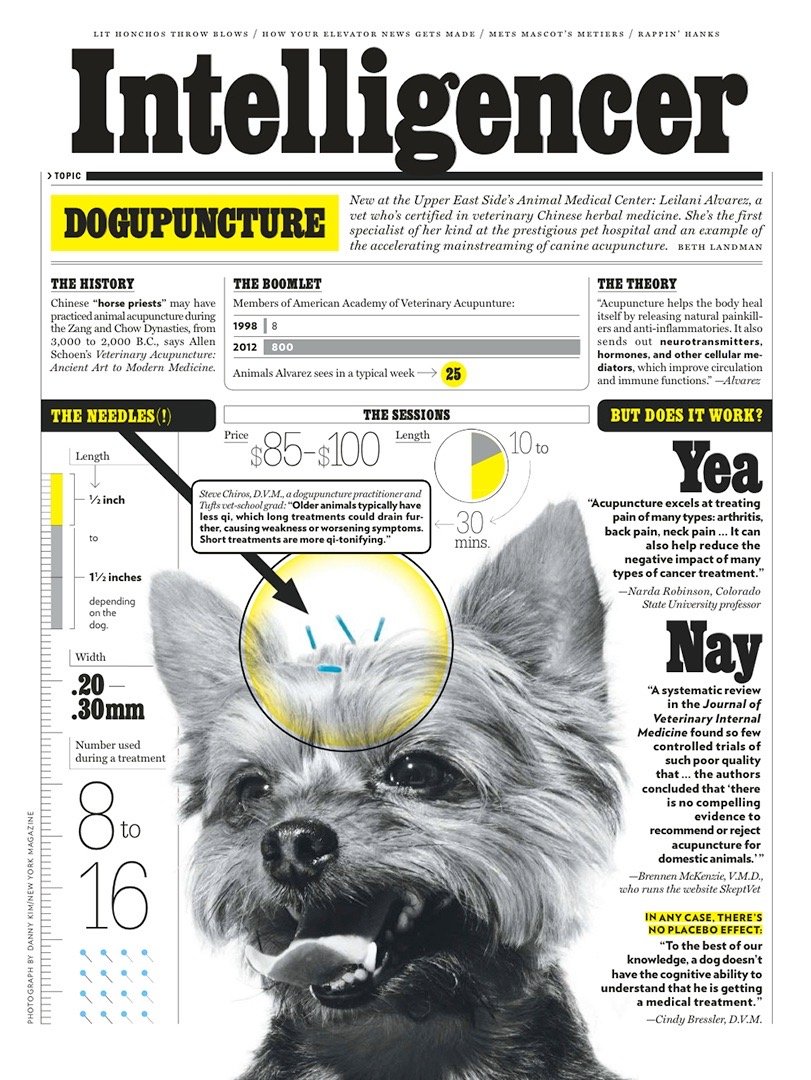

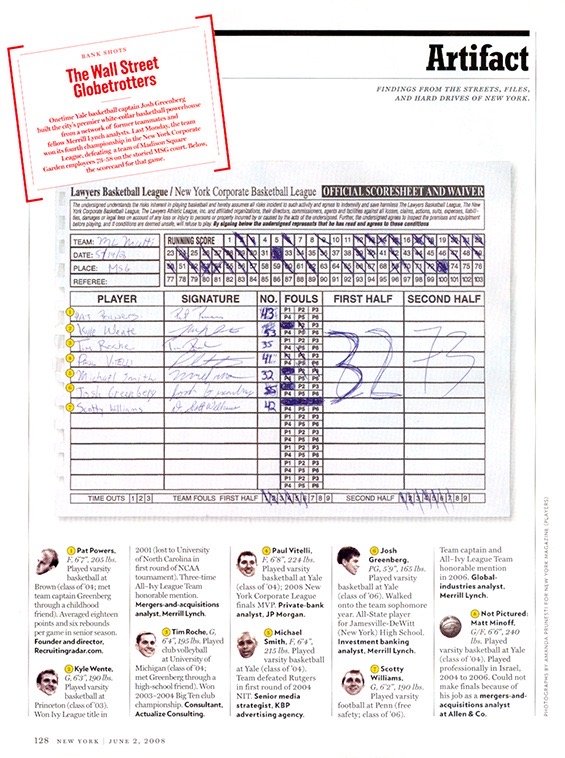

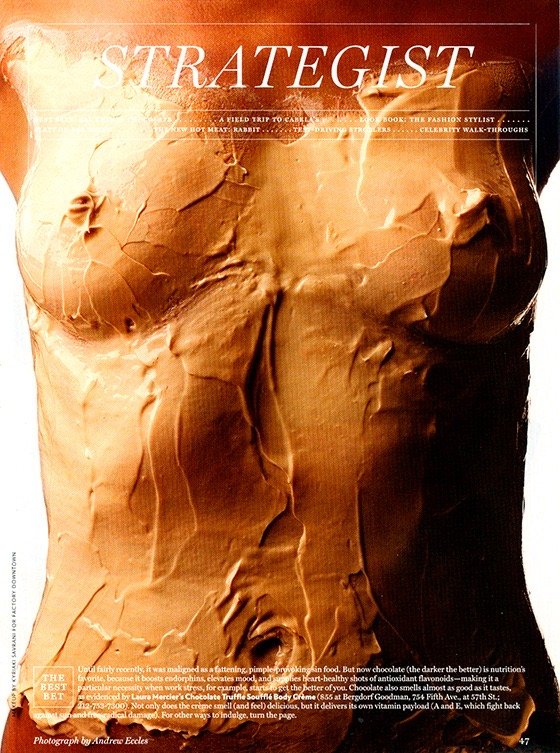

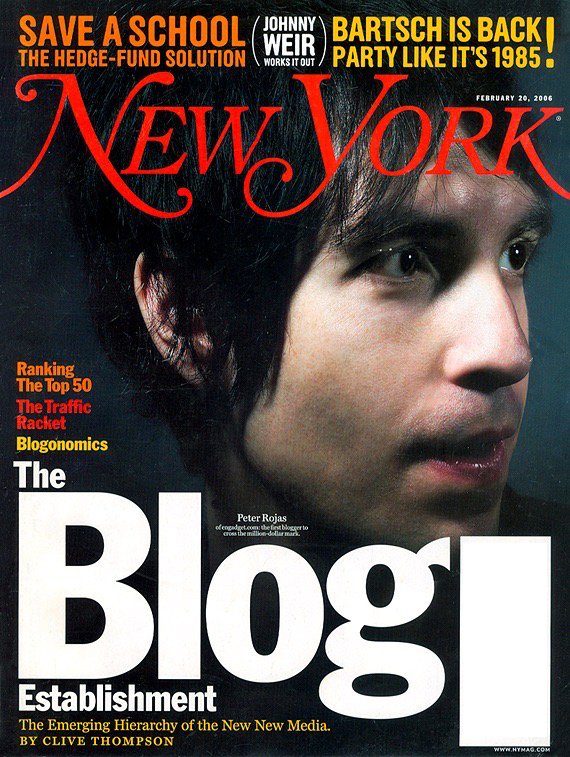

In 2004 Moss joined another venerable brand, New York magazine, where he not only completely reimagined the print magazine, he bear-hugged the encroaching internet menace, creating more than 20 new digital-only brands, five of which — Vulture, The Cut, Intelligencer, The Strategist, and Grub Street — remain heavyweights of modern online editorial.

In 2019, Adam Moss ended his 15-year run at New York, saying, “I want to see what else I can do.” So … painting. But, once obsessed, always obsessed. Moss is currently at work on a book about creation and creativity. The book will decode how creative geniuses transform an idea into something real. A song by Stephen Sondheim. A sculpture by Kara Walker. A film by Sofia Coppola.

Asked to describe what he’s making, Moss calls it a “big, overgrown magazine.” Of course he does.

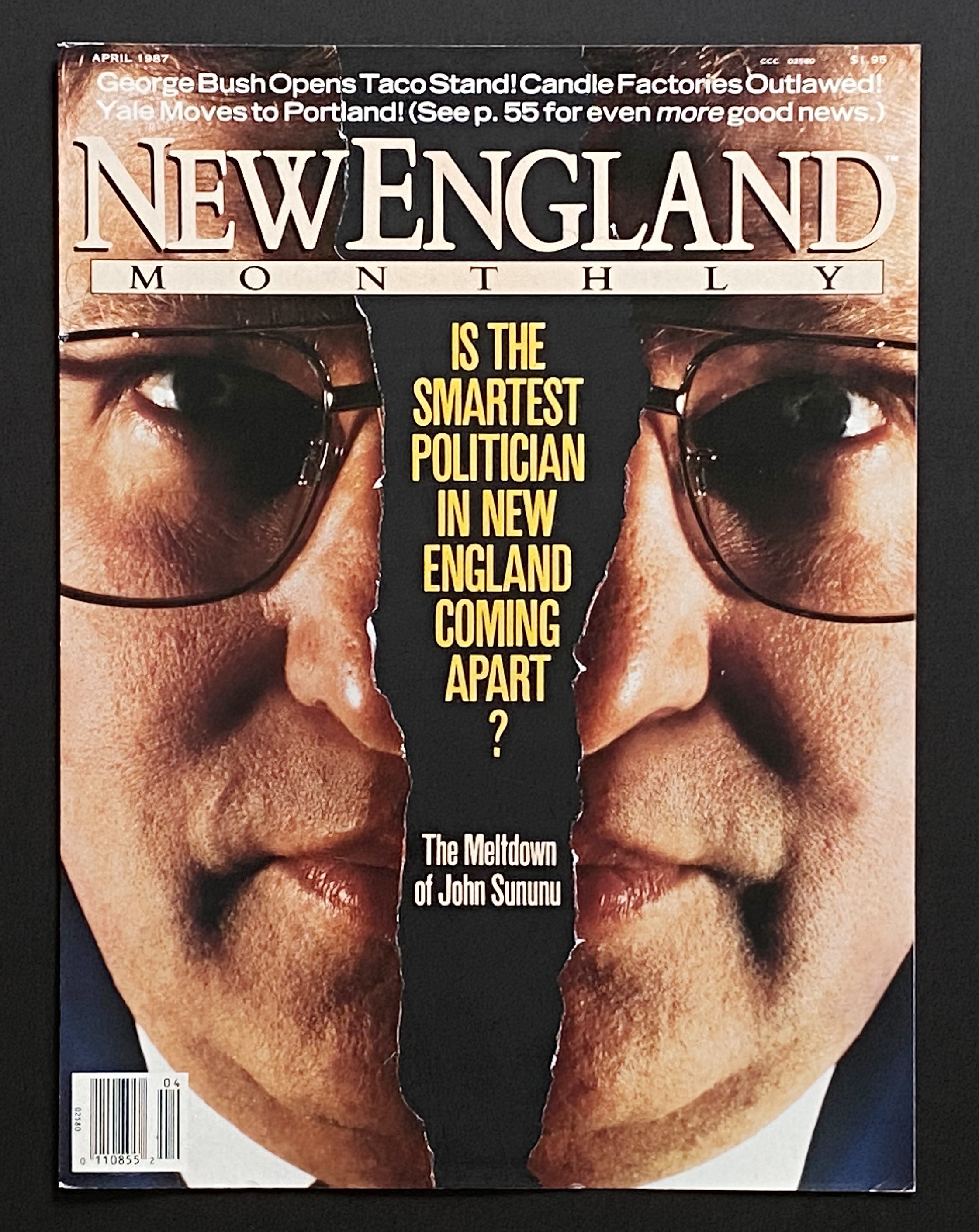

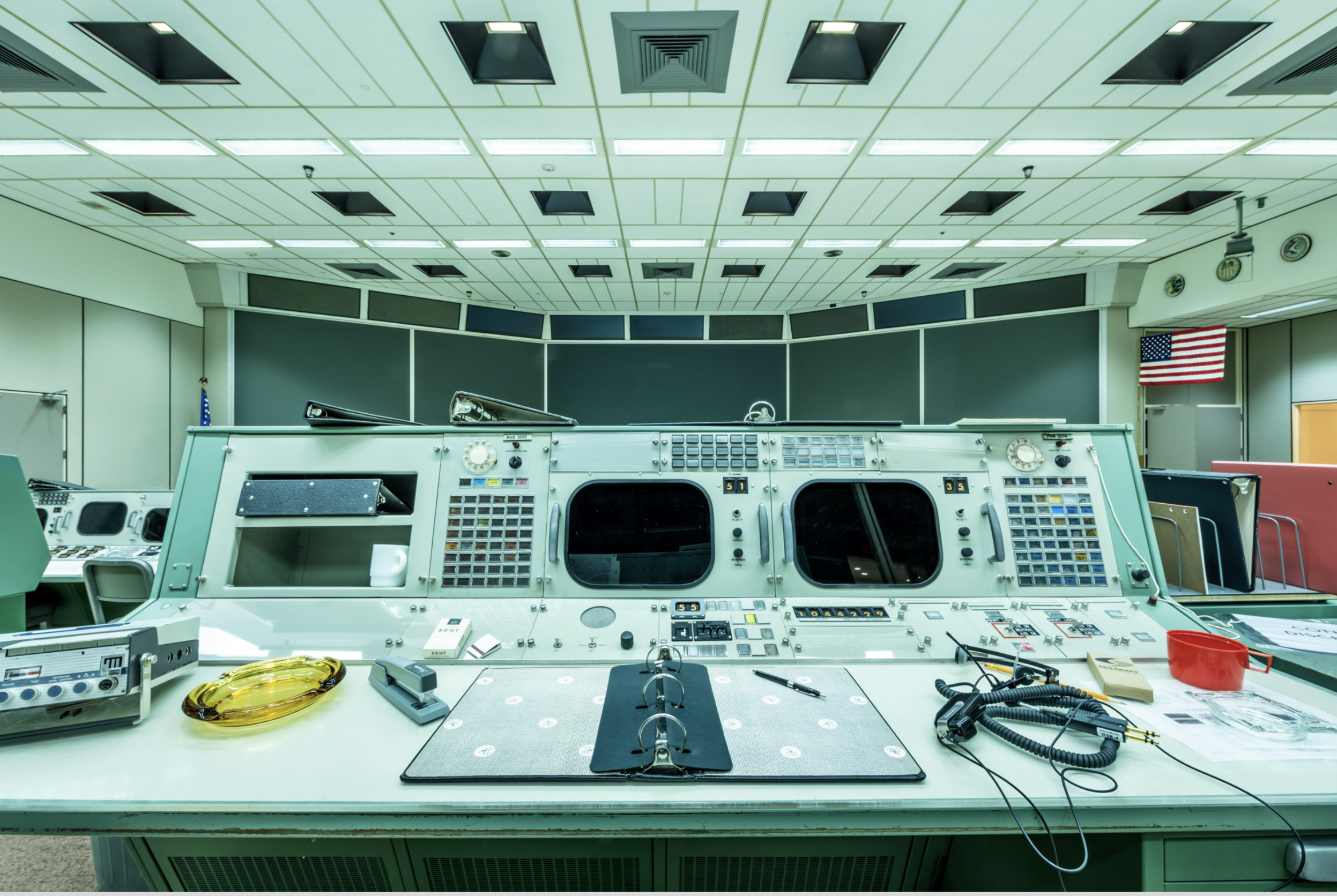

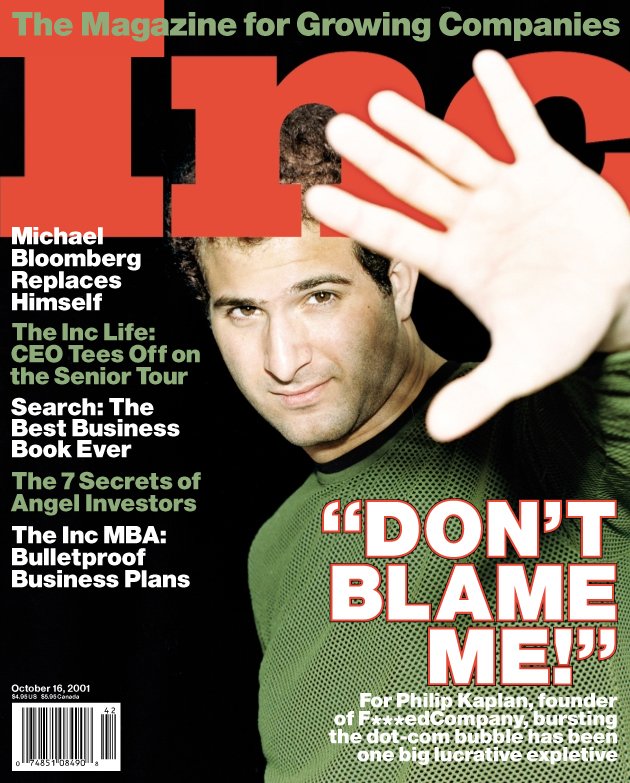

Moss launched 7 Days in 1987.

“Most of the time I’m just working by myself. And that has its own pleasures, but it’s not the same thing at all as that kind of group hug that is magazine making.”

George Gendron: So I want to start by asking: Do you miss all the attention, all the accolades, all the awards — even a little?

Adam Moss: No, actually, I don’t miss that at all. I always felt a little mystified by the attention and always ran away from it while also, of course, loving it. But feeling kind of embarrassed about the kind of attention an editor-in-chief gets, which is so, in my view, disproportionate to the amount of work that that person does.

The staff itself does all the work. So, I was always proud of the accolades on behalf of the staff and embarrassed about them on behalf of myself. But what I miss is not any of that at all. What I miss is the actual work. Which is to say, the work with other people. I miss the camaraderie of the magazine. That was the best part of it.

George Gendron: And given what you’re doing right now, you don’t have much of that, do you? Or any of it?

Adam Moss: No. I try to create little versions of it here and there in my life. I’m working on a book and the book involves design, so I’m fairly happily working with some folks at Pentagram.

The lead person is Luke Hayman, who was art director of New York. I hired him when I got there. Wonderful. And his wonderful team. And I have these consulting gigs which are somewhat social, I suppose. They involve working with other people. And those are very, very satisfying.

But no, most of the time I’m just working by myself. And that has its own pleasures, but it’s not the same thing at all as that kind of group hug that is magazine making.

George Gendron: Let’s go back to the book. What can you tell us about it?

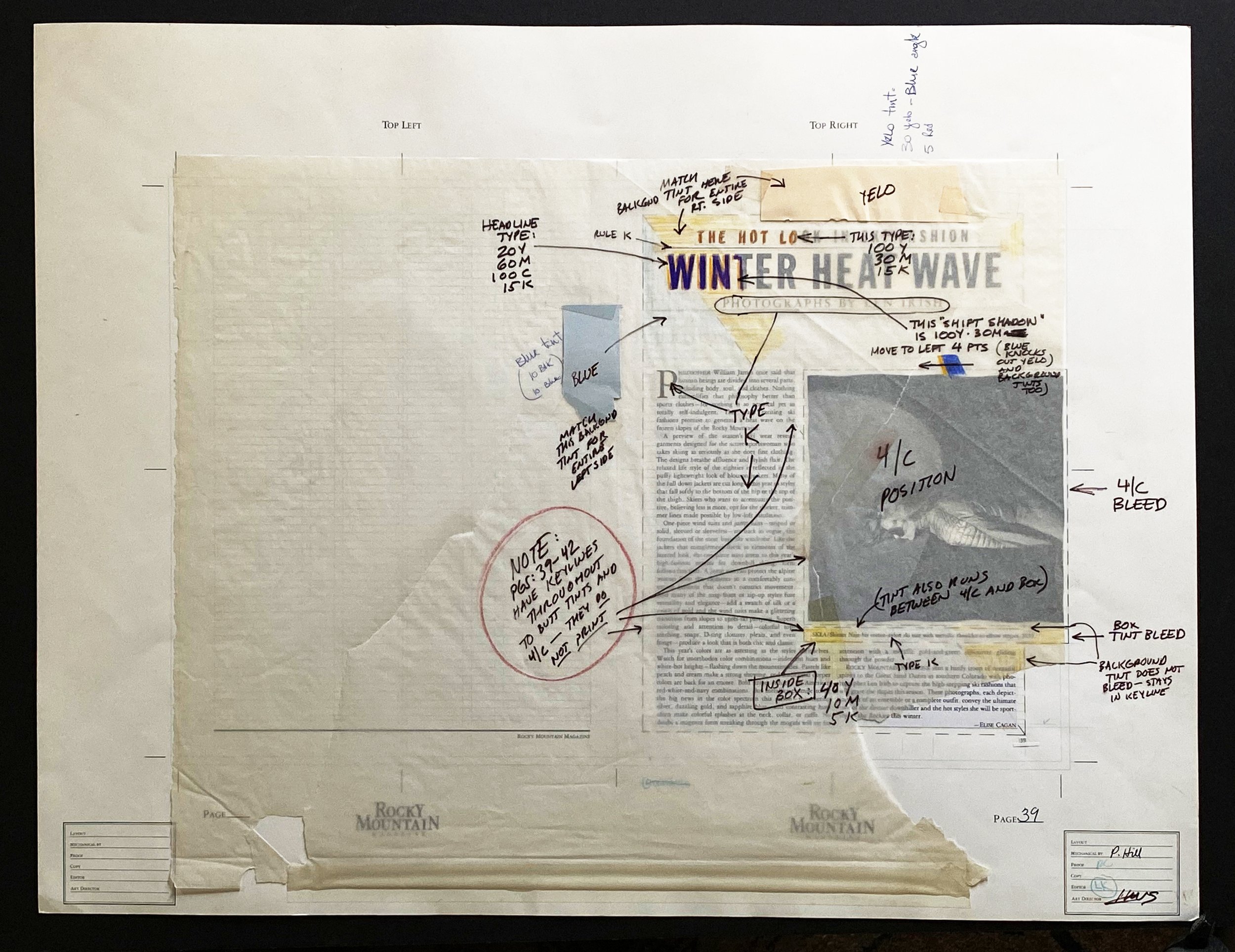

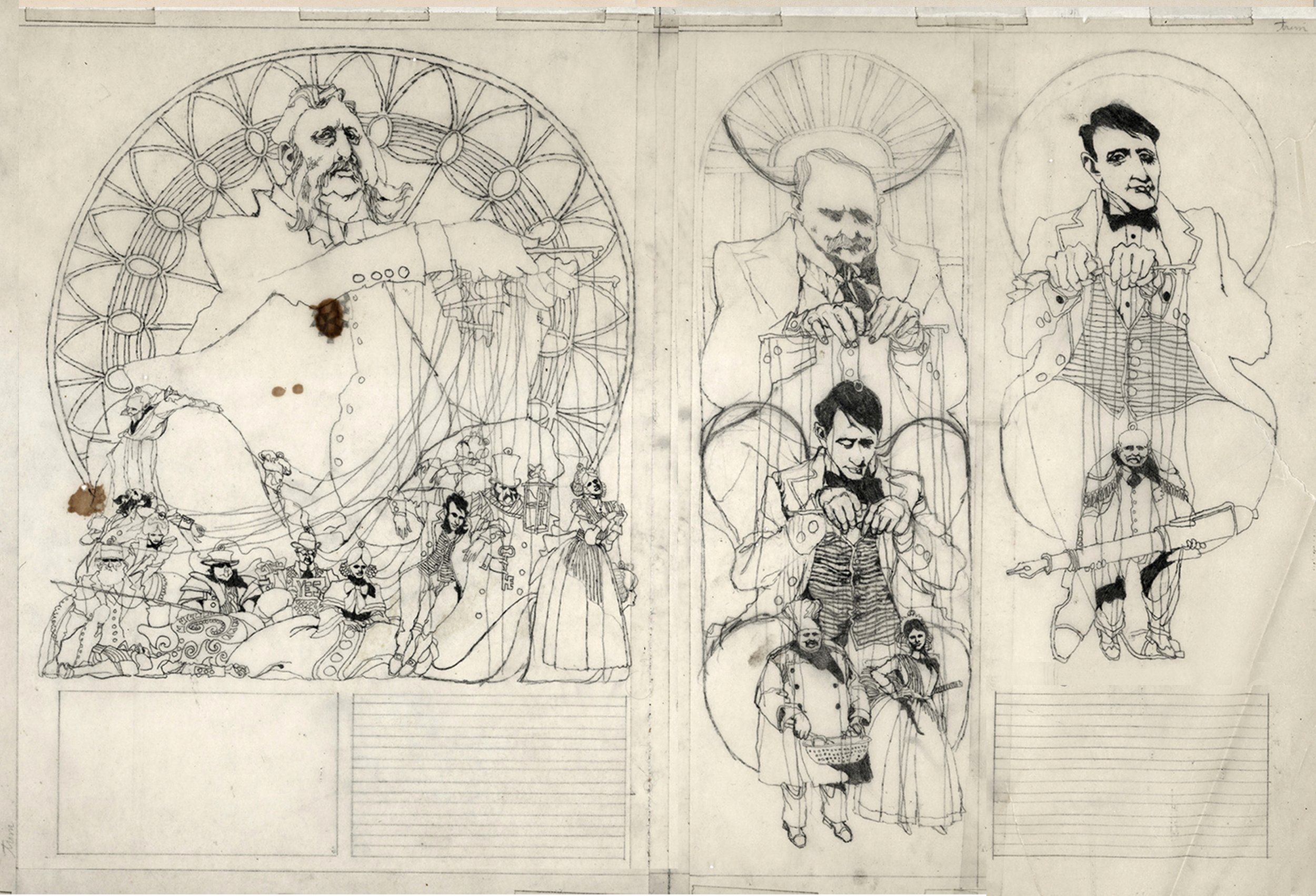

Adam Moss: Well, I don’t want to say a whole lot at this point, but it’s a book about how artists think or, I guess, more loosely “creative process,” a phrase I don’t like, but I’m stuck with. And it traces the evolution of certain works through conversations with the artists and artifacts of the process of making the thing.

You know, there’s a chapter on Stephen Sondheim — I talked to him before he died — on the making of one of his songs. There’s a chapter on Louise Glück, the Nobel Prize winning poet, on a poem. A chapter on George Saunders and the writing of Lincoln in the Bardo book that I love. Kara Walker and the making of her sculpture called A Subtlety, that big, sort of “mammy sphinx” that she had in Brooklyn. You know, Sophia Coppola on Lost in Translation and Marie Antoinette.

Anyway, it’s kind of case studies on making creative things, and then trying to come up with some theories about why it works when it does. The book is, it’s a little bit of like a, it’s like a big, overgrown magazine is really what it is.

George Gendron: In terms of the form factor? The size?

Adam Moss: Yeah, the physicalness of it. I mean, you read it, you look at images, you cross back and forth between the images and the words. It’s not like there’s imagery segregated in one part of the book and then words in another. It’s all very much tumbled together. And what I hope feels a little bit different in book form.

George Gendron: You and I talked a couple days ago about this and you said it might include photographs, artifacts…

Adam Moss: Yep.

George Gendron: …And it left me with the impression that what you are really trying to do is kind of decode the process that an artist goes through from an initial idea to the finished product, and you might get to see the evolution of that idea.

Adam Moss: Yeah. That’s exactly right. That’s, I mean, that’s the aim. And, you know, these documents, or the artifacts or specimens, or — I call them all sorts of things, exhibits — they’re amazing, for the most part. And especially those that are kind of "notes to self."

George Gendron: Yeah.

Adam Moss: These, sort of, journal entries that the artists are writing, or are sketching, as they’re making the thing. You can actually just feel teleported into the artist’s brain. Which I personally find enormously satisfying and interesting. Much more than my own words about it. These artifacts are kind of rich archeological finds.

George Gendron: So it sounds as if we’re going to get to see the Adam Moss editing sensibility at work, in this case, in a book.

Adam Moss: I guess.

George Gendron: Oh, come on.

Adam Moss: Sure. Yes. That’s right!

George Gendron: Drop that humility, man.

Adam Moss: It’s an editor’s book.

George Gendron: That’s what I was getting at. Yeah.

Adam Moss: Yes, I think it is. But, as mentioned before, it’s very much a book in which I’m playing all the parts. I feel like it’s a Marx Brothers movie where I just keep running in one door and out the other door. I’m the writer, I’m writing the captions. I’m dictating the way I think it ought to look. And I’m just doing it. I did the interviewing, I’m the writer, I’m the... I’m everything. And it’s kind of hilarious. But it’s quite different from the “groupness,” just getting back to how you make a magazine.

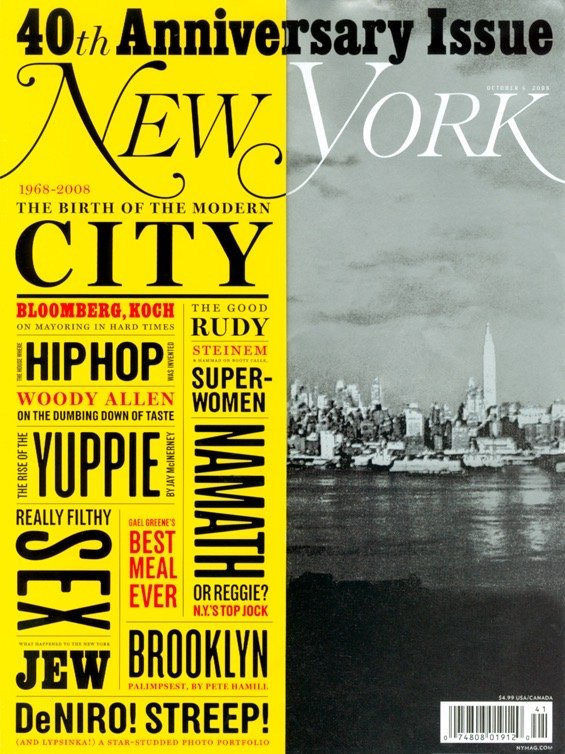

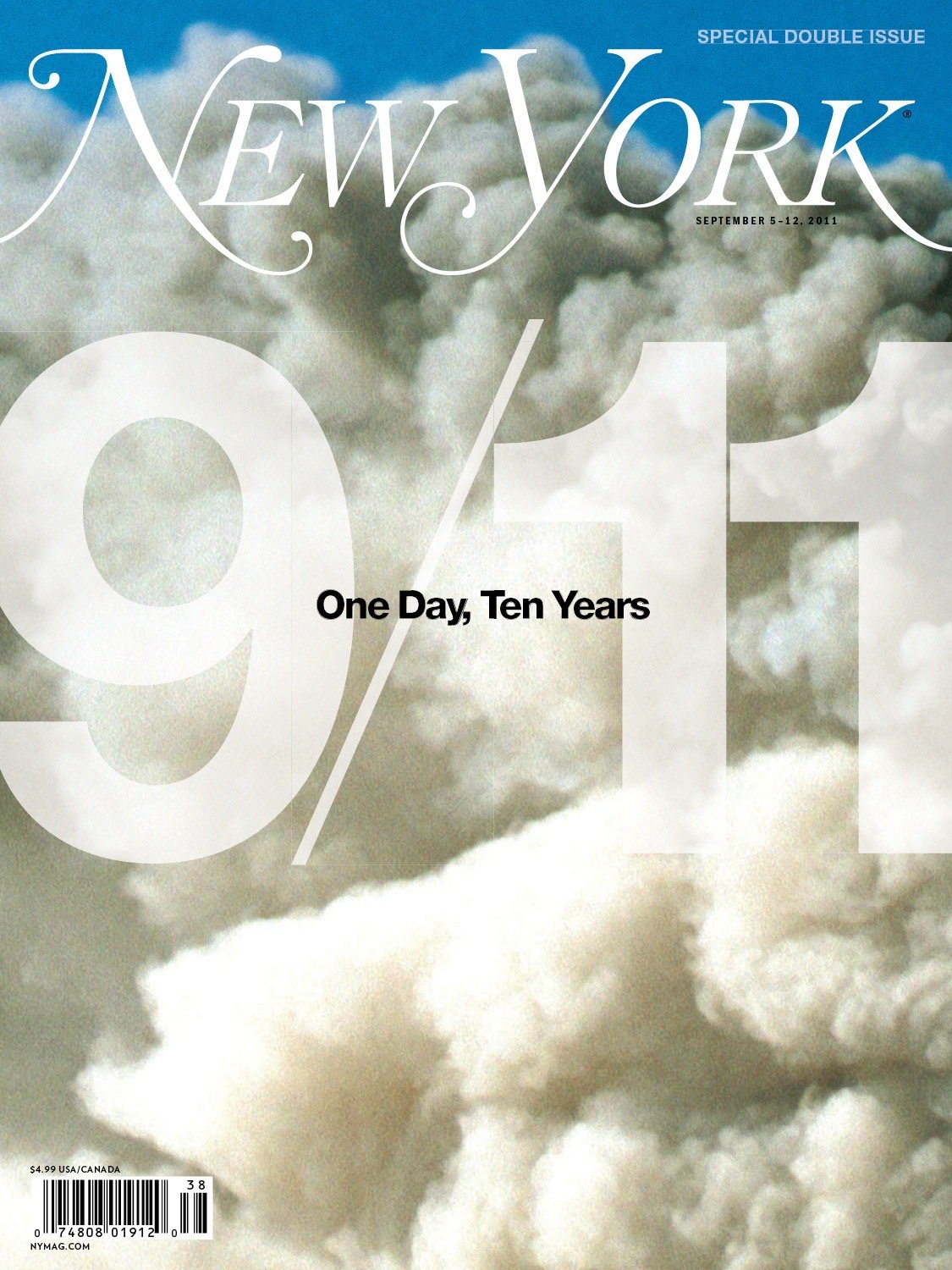

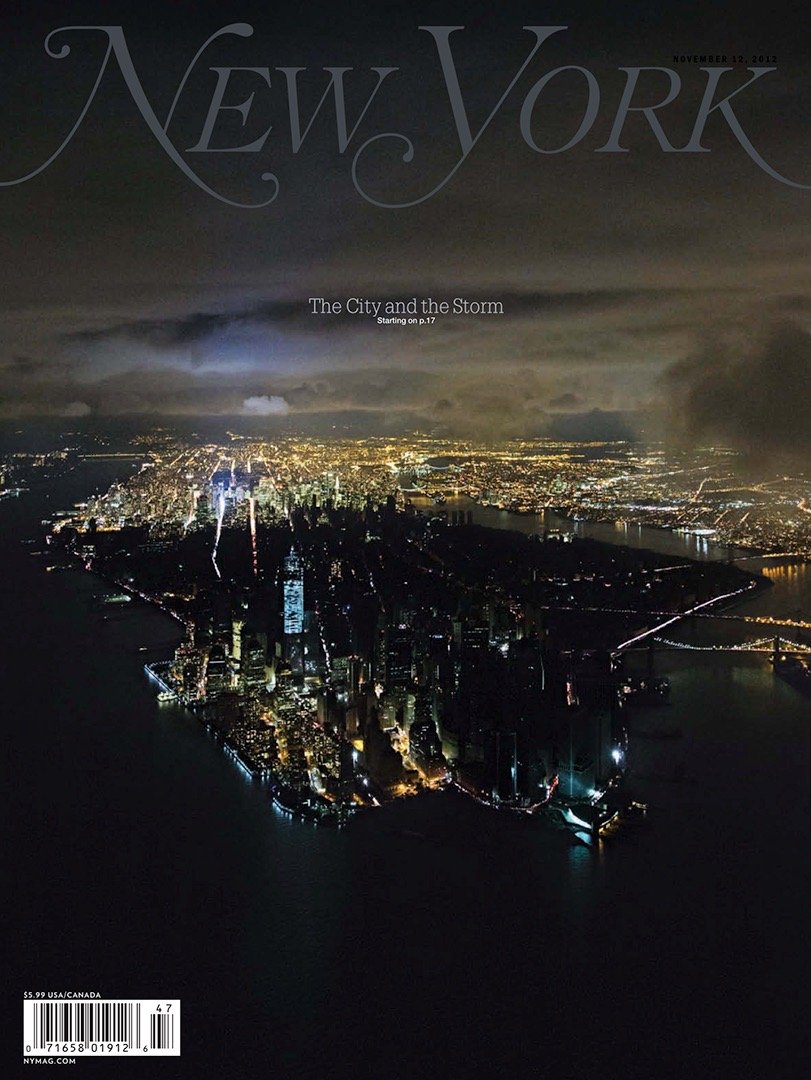

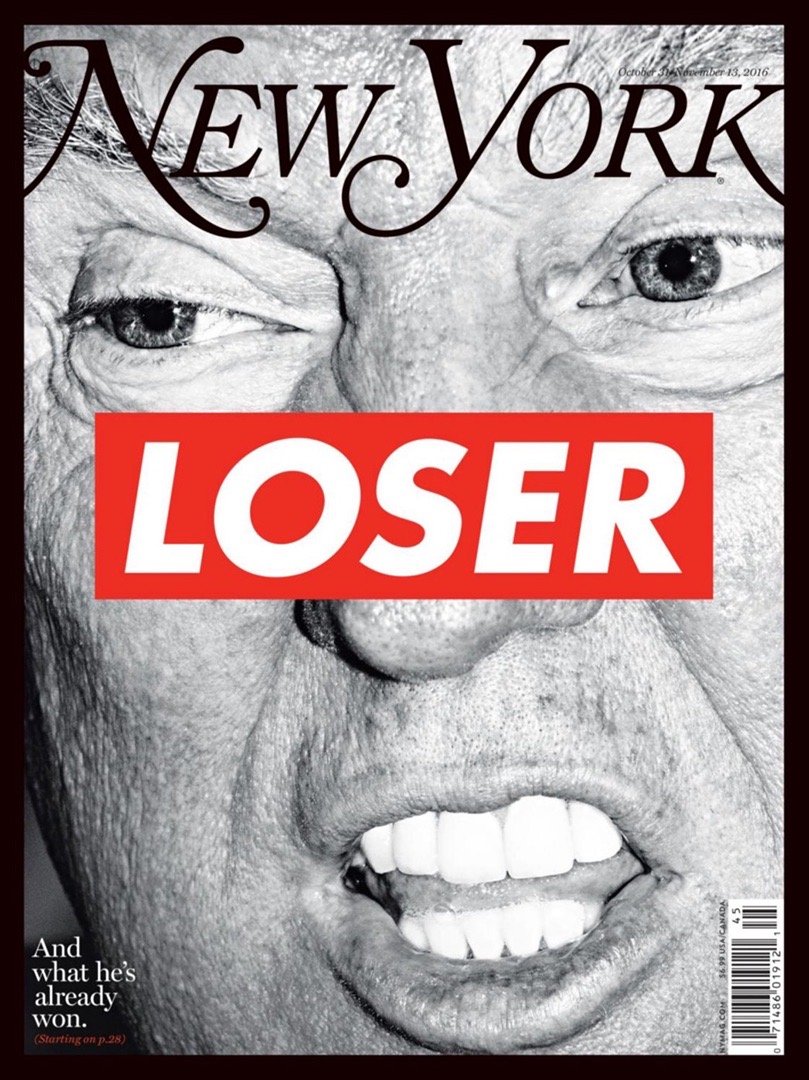

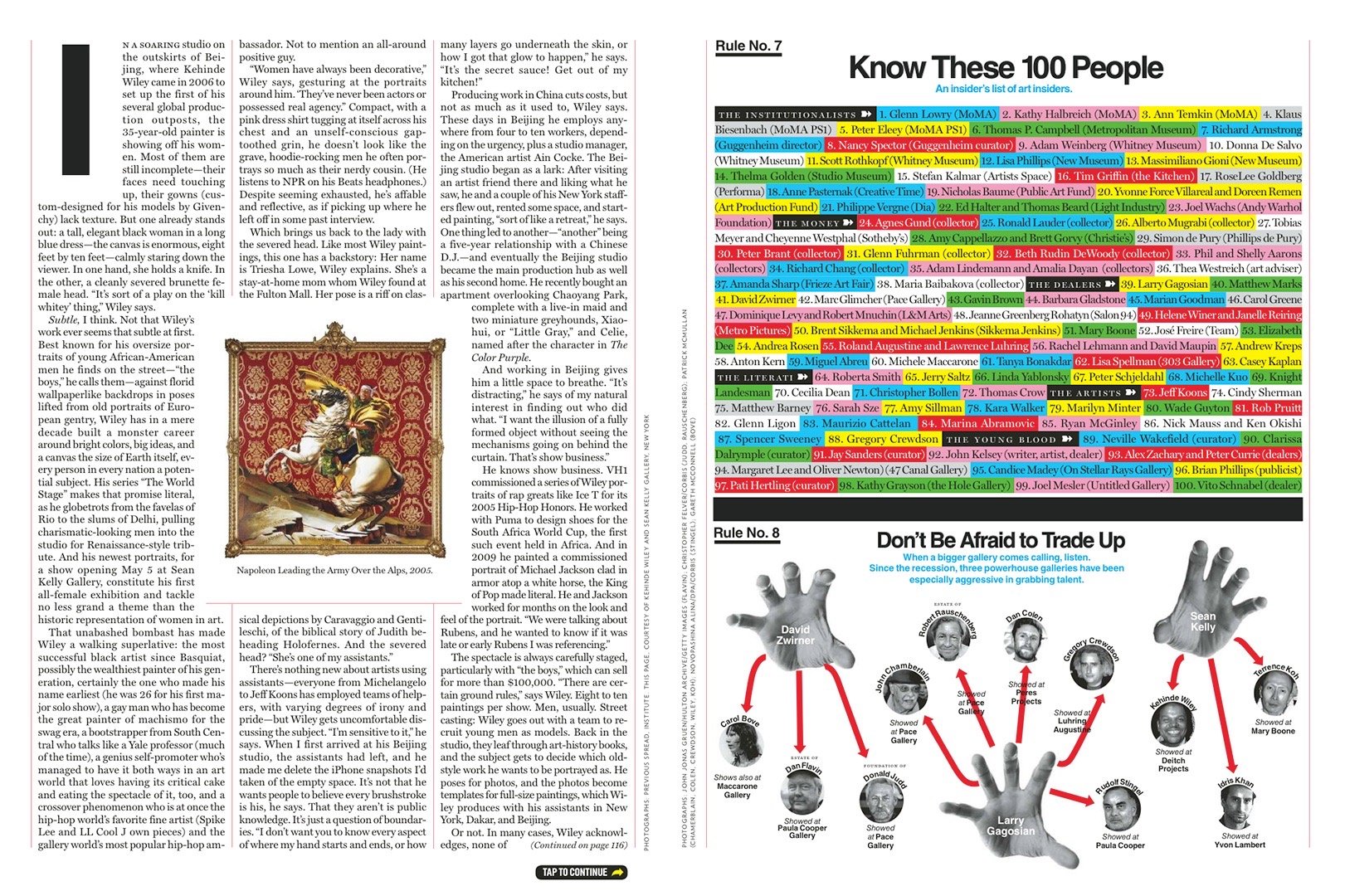

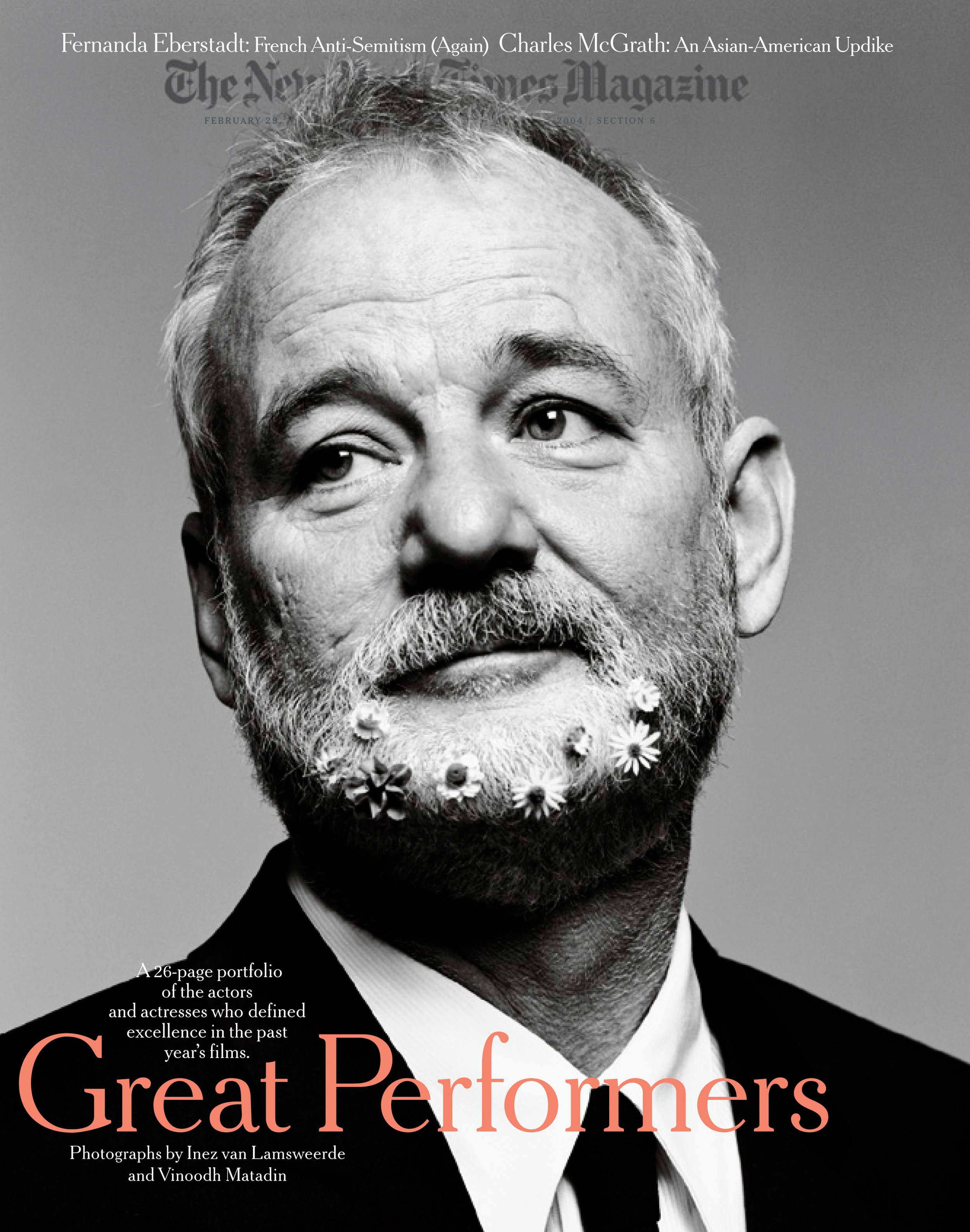

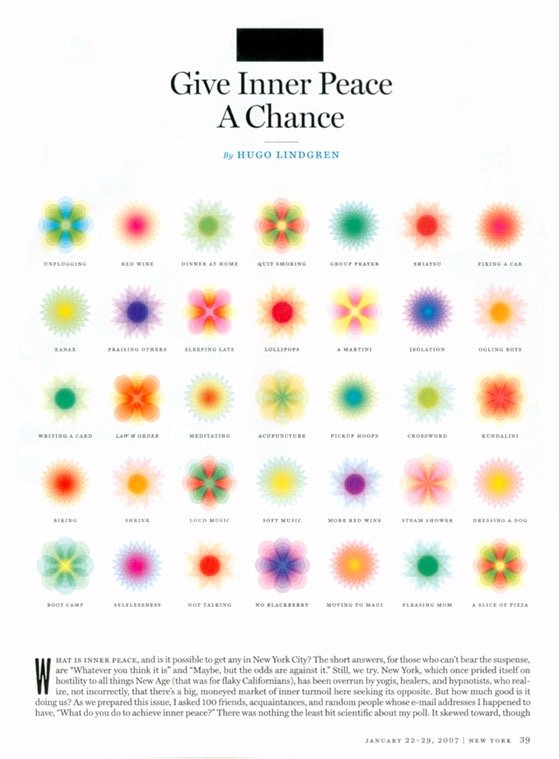

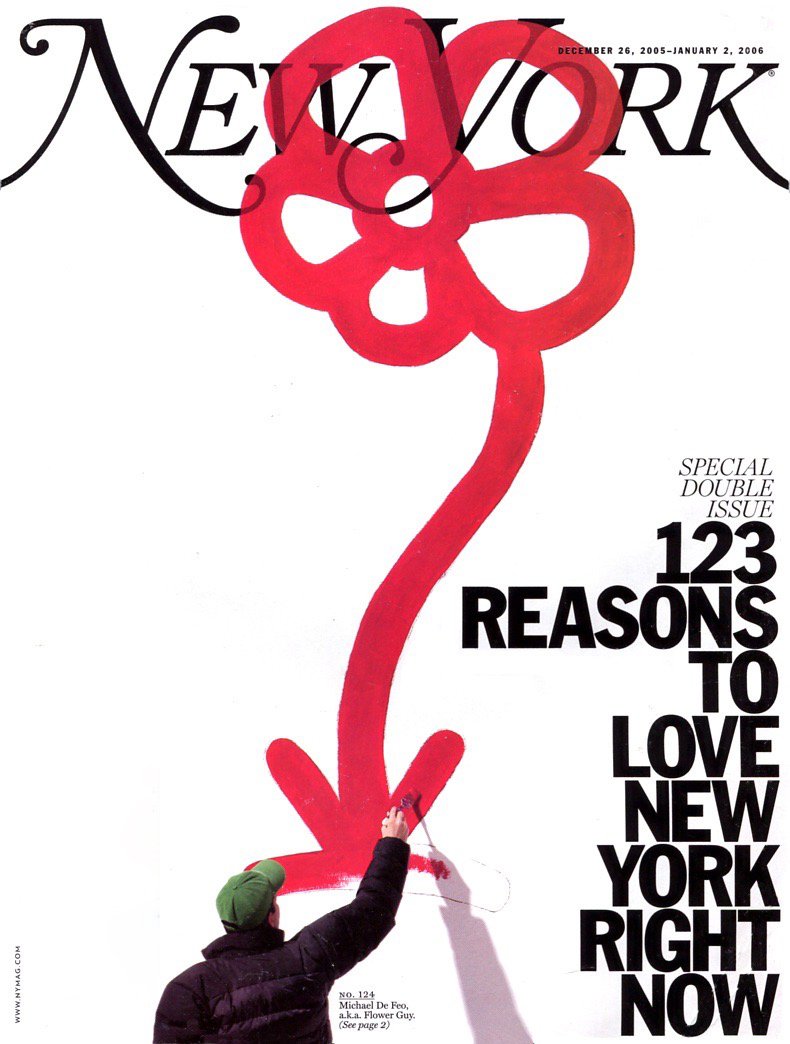

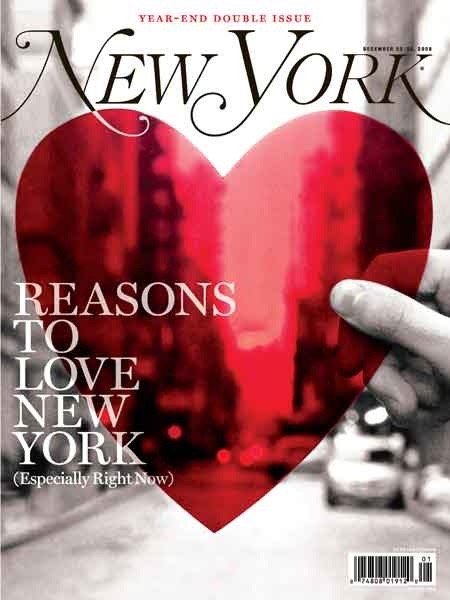

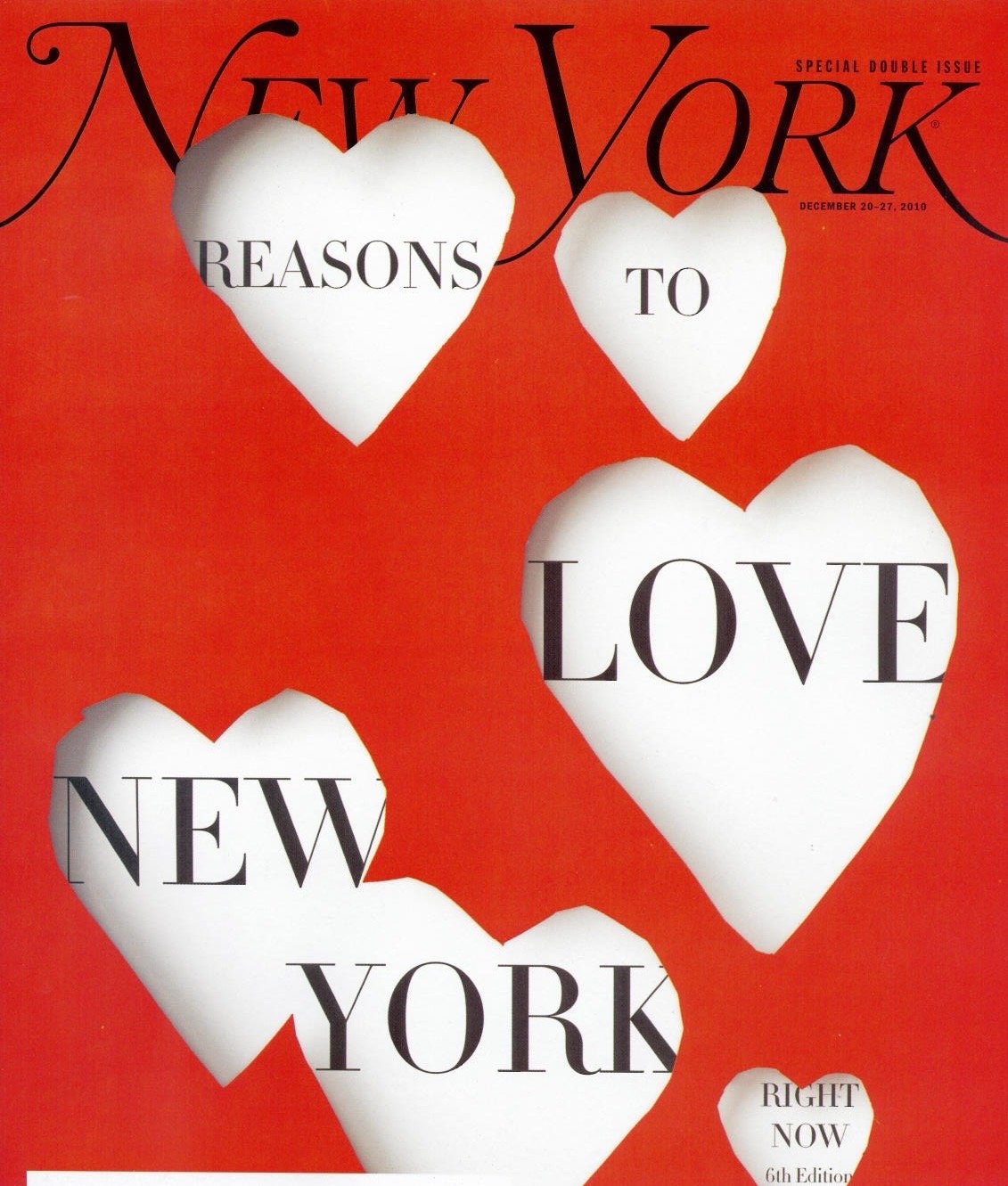

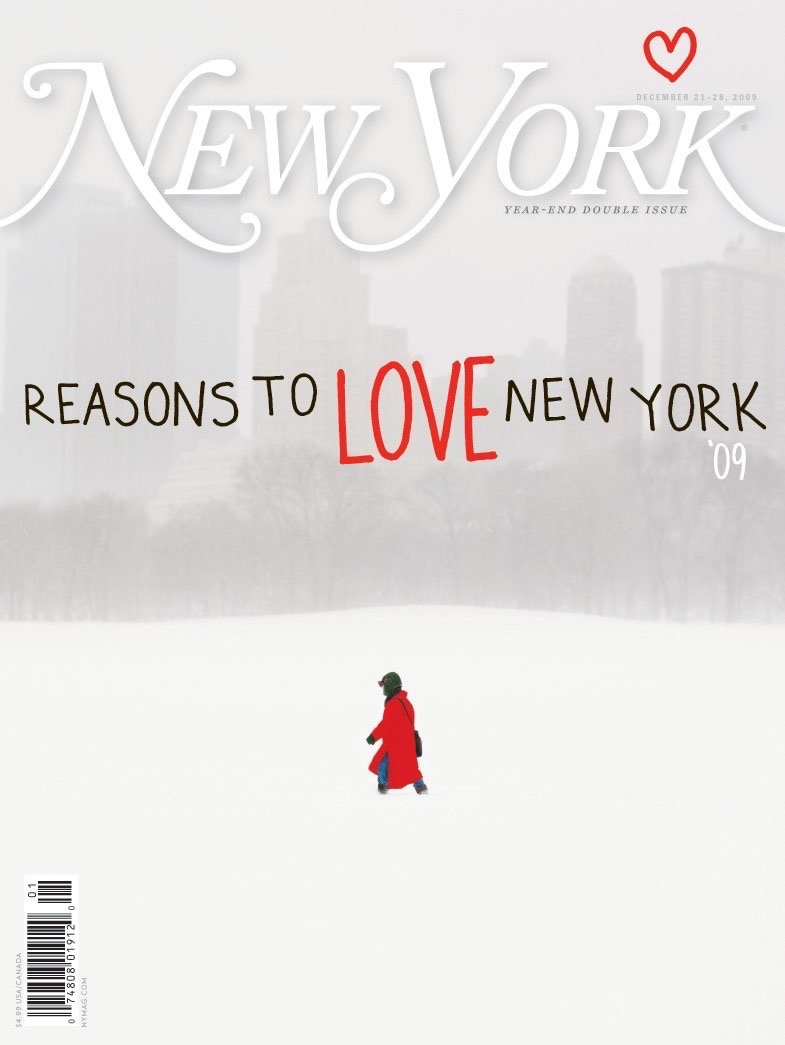

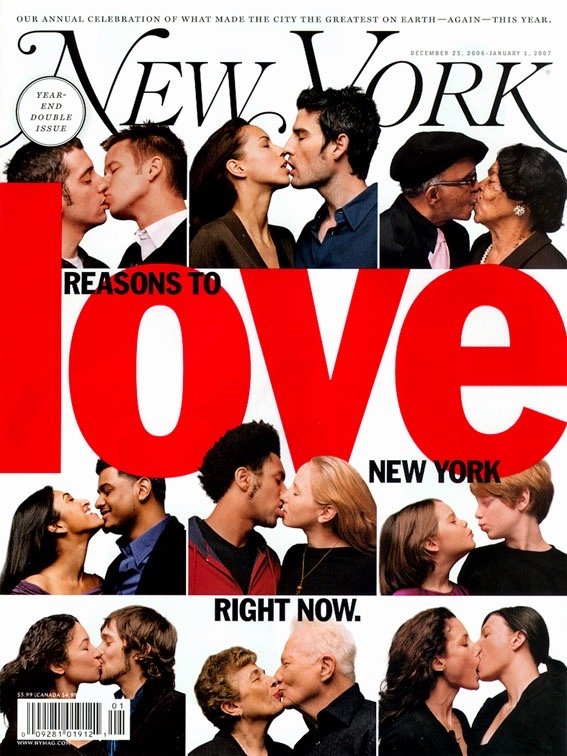

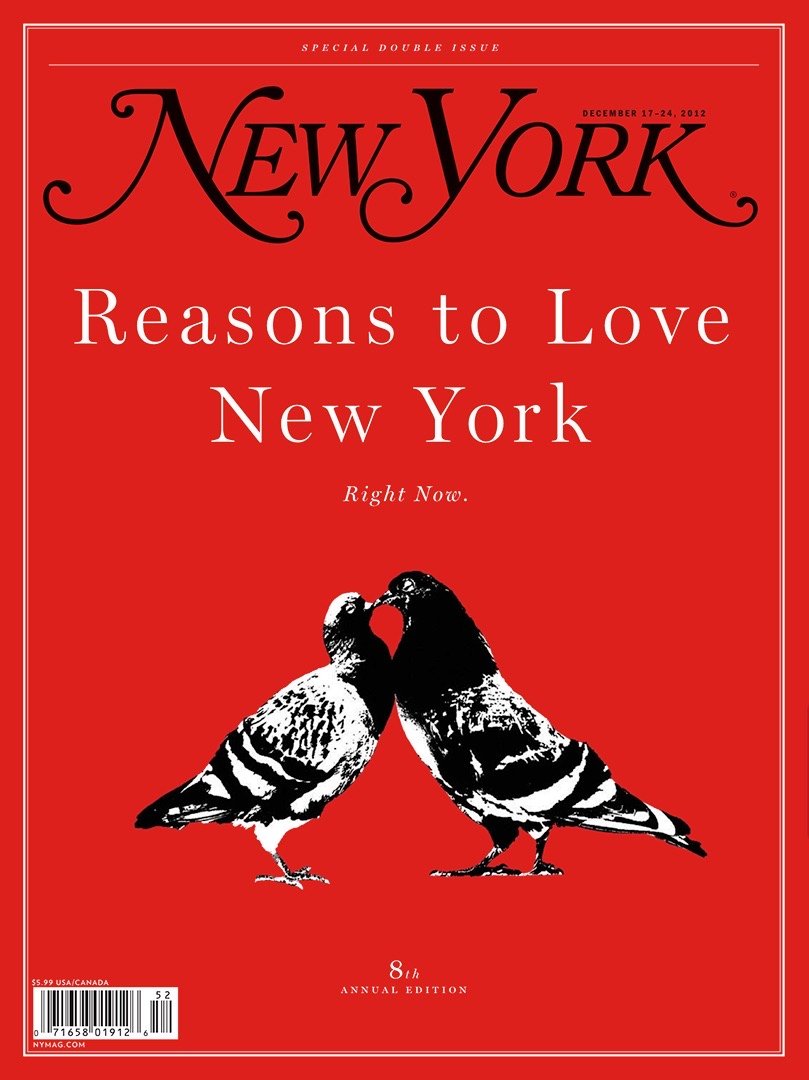

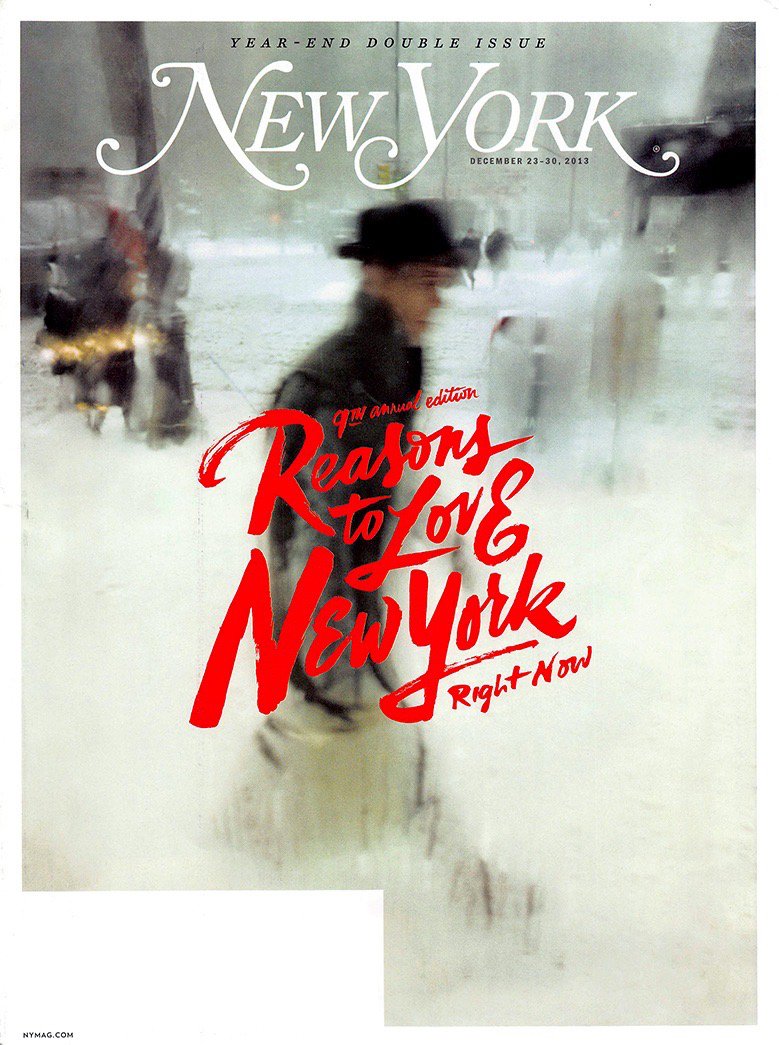

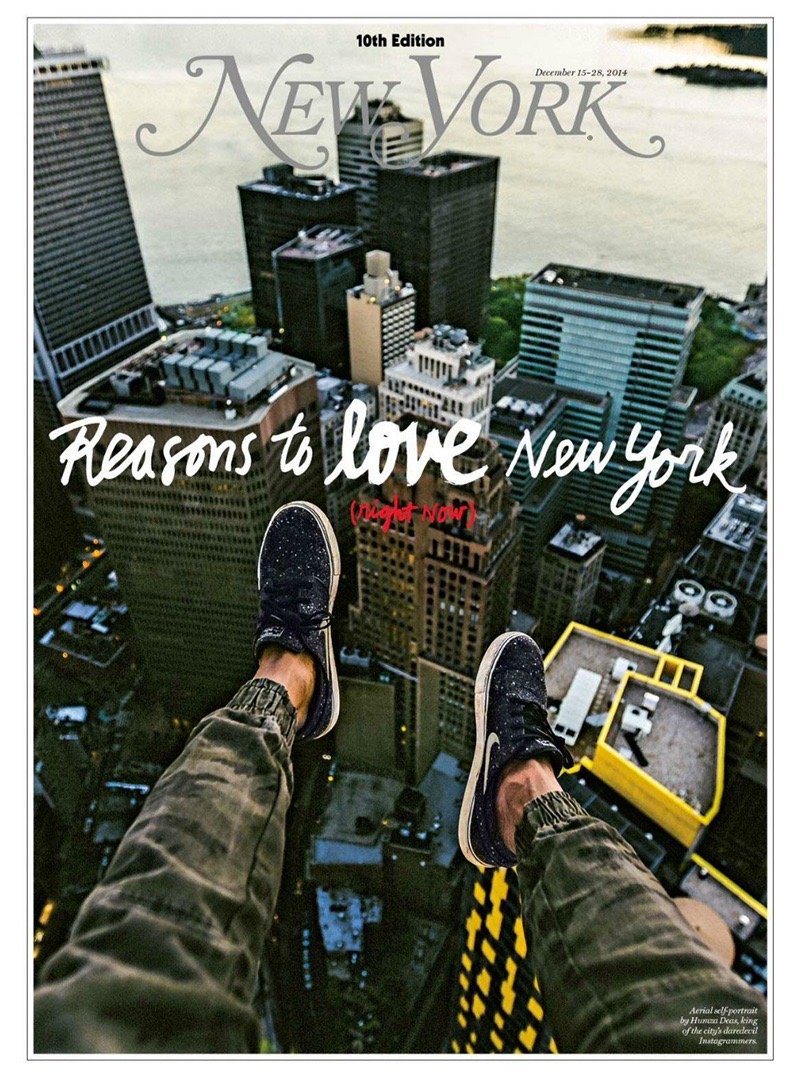

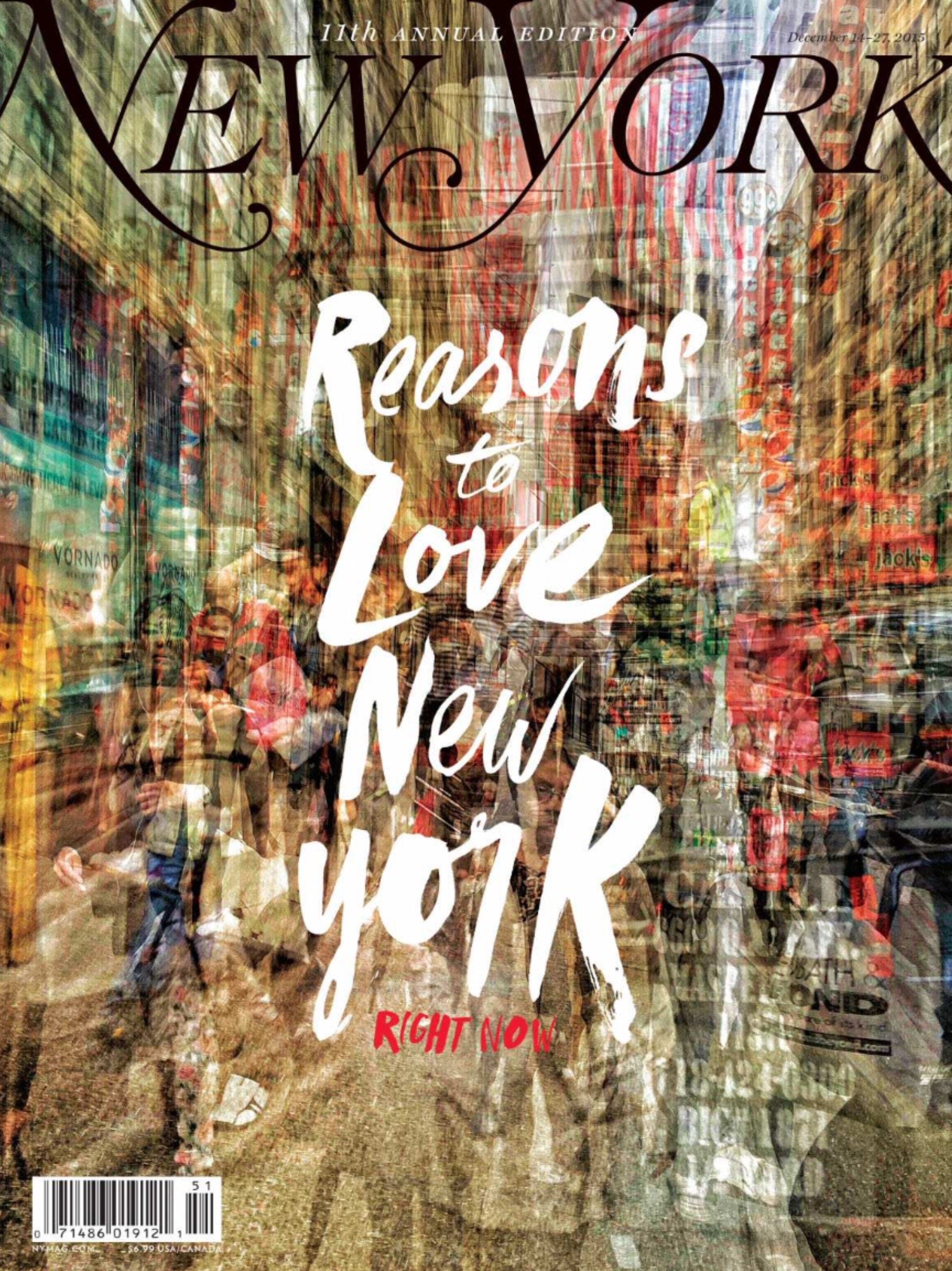

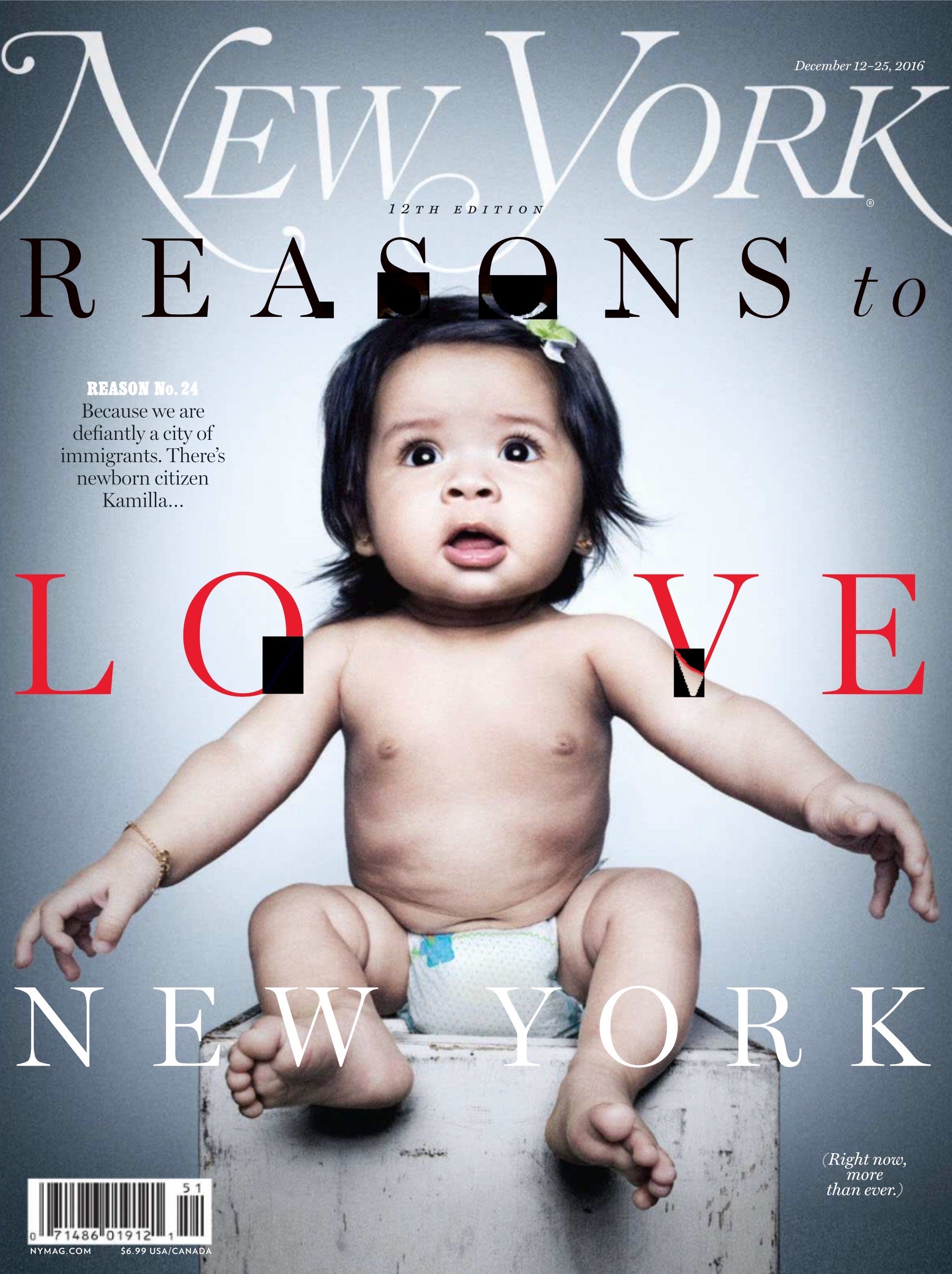

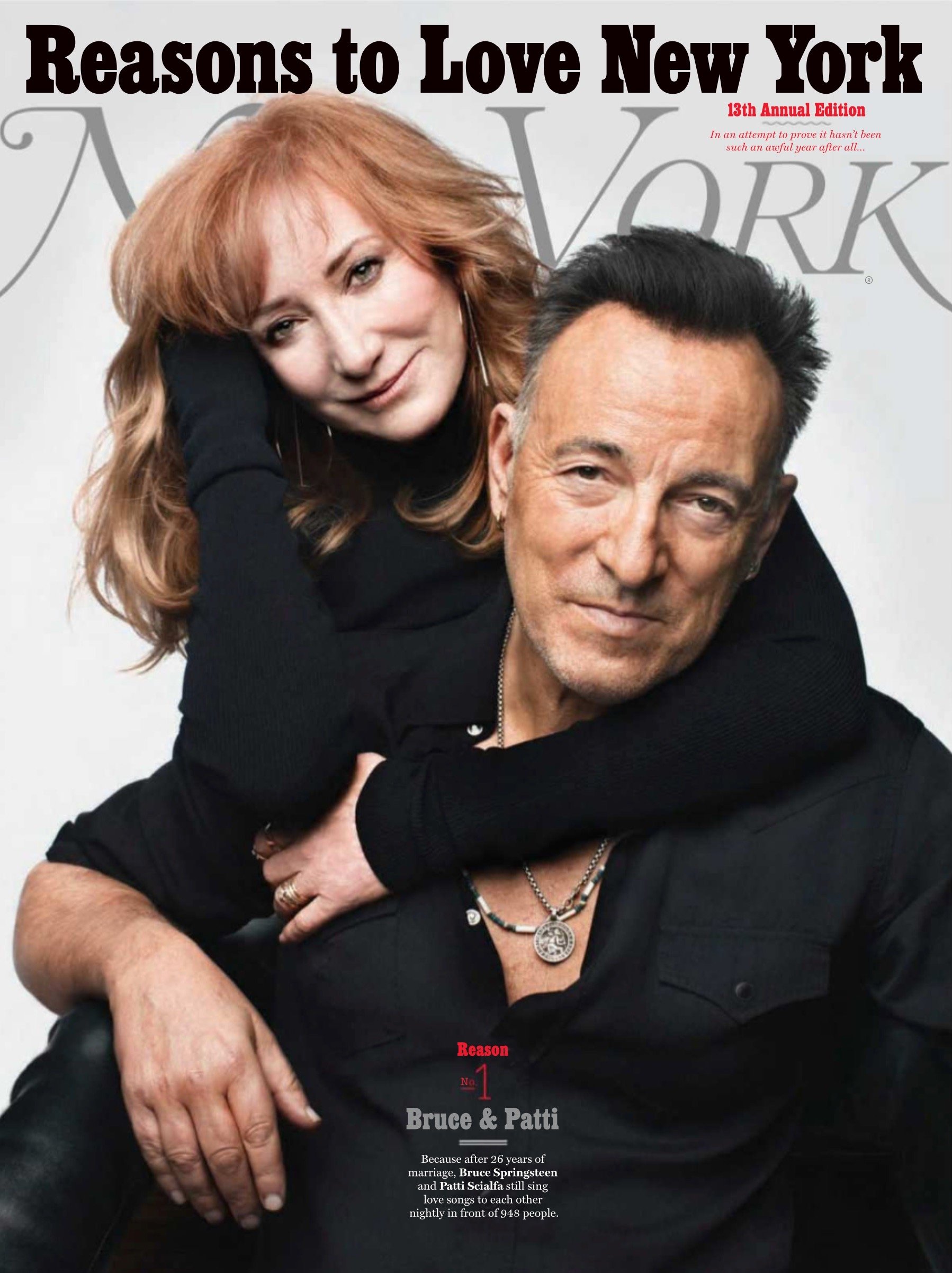

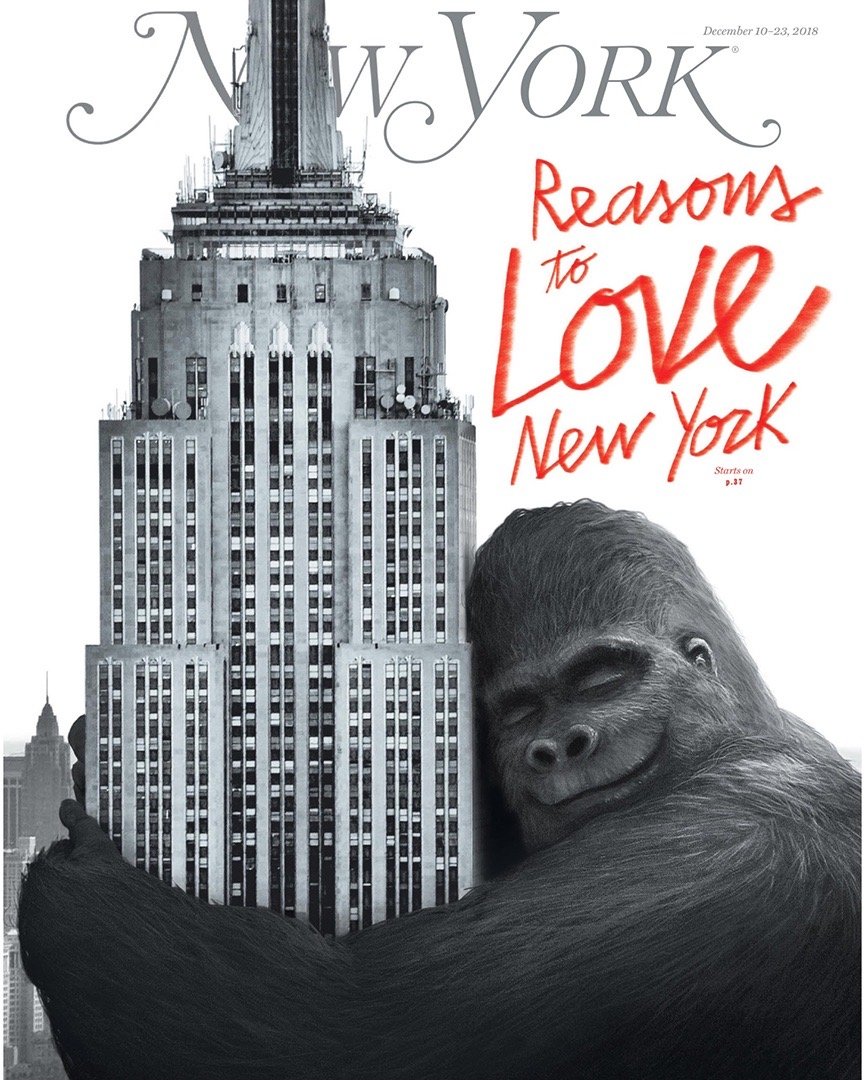

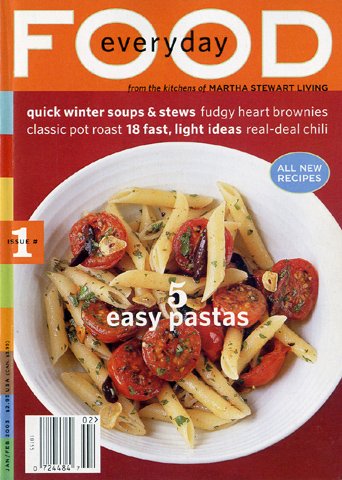

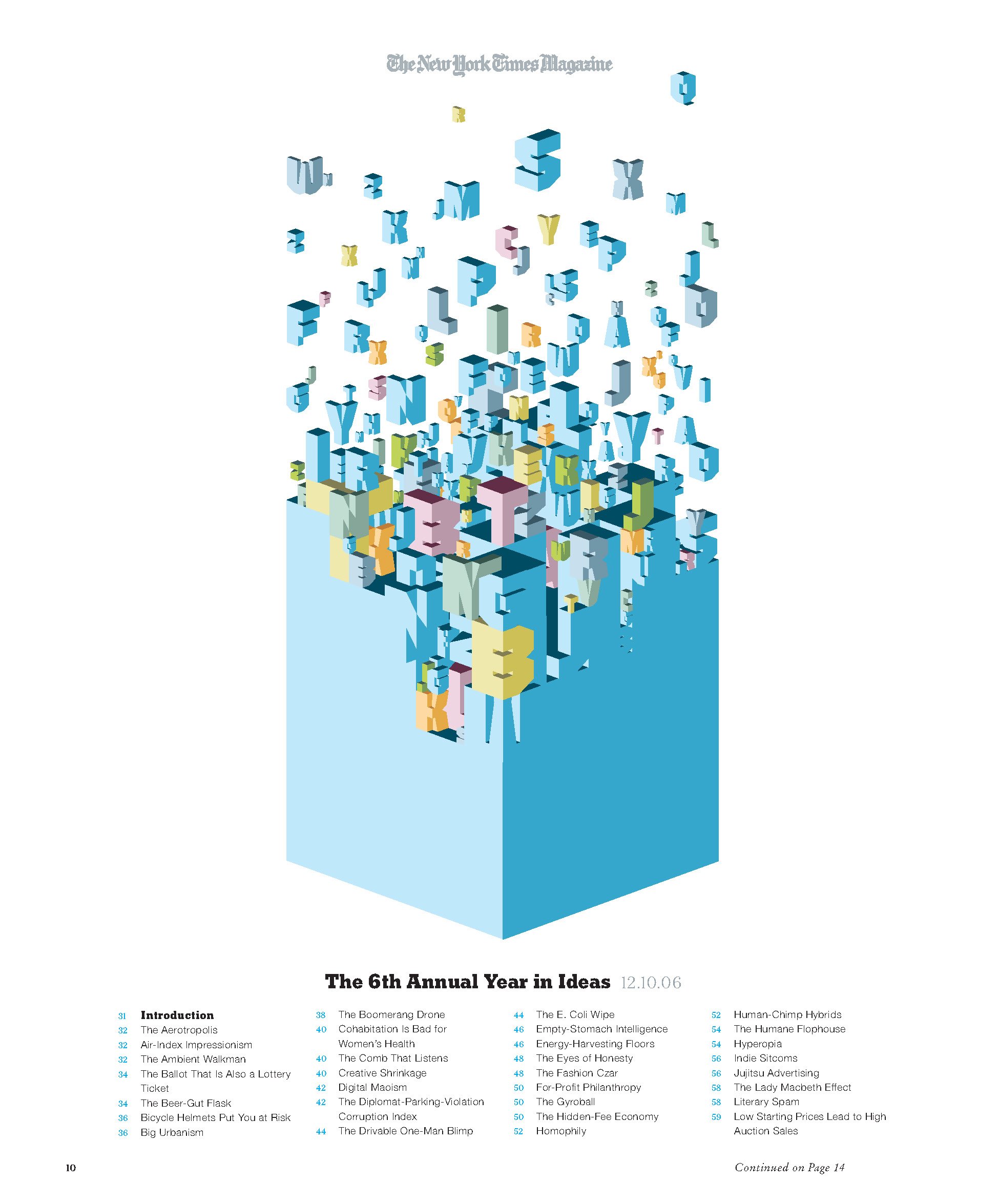

A few of Moss’ favorite New York covers

“The ownership of the magazine before I got there wanted a magazine in the mold of the imitators of New York magazine rather than New York magazine itself. So it had lost, in my opinion, an essential part of its DNA.”

George Gendron: A lot of people have said to me in a different context, “When are you going to write a book, or “the book” about entrepreneurship or innovation and creativity?” And man, I have just no desire to write a book. I just know too much about how hard it is. And then my partner, Patrick [Mitchell], who’s producing this, at one point said to me something really interesting. He said to me, “Don’t think about it as writing a book. Think about it as making a book.”

Adam Moss: Well, that’s exactly the verb I use to do this. I created this book deliberately in a way that it would be “writer proof.” I mean, I myself, hate writing so much that it would be a book that, really, the writing would be the least important part.

George Gendron: Boy, do I identify with that! So great, you’re going to be an inspiration to a lot of editors to write. When does the book come out?

Adam Moss: It’s not clear. It’s due kind of soon. But the way book publishing works is that that’s just the beginning of a long, long process. My guess is spring of 2024.

George Gendron: Are you going to meet your deadline?

Adam Moss: Yeah. You know, I’m a good, good student. I try to please the teacher.

George Gendron: That’s good to hear. But we’ll look forward to the book. So what, if anything, can you tell us about the consulting projects? Or are you all NDA’d up?

Adam Moss: Well, I’m not technically NDA’d up. But I think these relationships are best when they’re private. I’ll just tell you that they’re, basically, working with various journalistic outfits that seek me out for whatever reason.

And you know, I perform all sorts of different kinds of roles: a sounding board, a shrink sometimes, sometimes evaluating ideas and giving feedback on them, evaluating manuscripts and giving feedback on them. But basically just someone to talk to in a kind of discreet way.

And it’s very satisfying to me because it allows me to function as a journalist without a lot of the things that I had come to not like about journalism, mainly management. Which becomes, as you get more positions of responsibility, that also means that you’re spending a lot of time worrying about management, a lot of time worrying about business strategy, and all these other things.

Especially when, toward the end of my tenure as an editor, when things got very complicated, in terms of the economics of magazines. It sort of distills the pure journalism of it. So I like all that. Even though, basically no one has to listen to me. That’s a little frustrating. You know, you give your thoughts and then that’s it. You’re finished. Somebody else decides whether they’re worth anything or not.

George Gendron: It’s interesting. A university did a case study about the culture that we created at Inc. And it turned out that there was something that I mentioned very casually to them that became a big deal. And I actually felt that I learned a lot from the case study. Which is often the case, right? We do things intuitively, but we don’t really think about the intentionality behind it. And at one point I had said, “You know, I really don’t like to manage and I think I’m really bad at it.” And as a result of that, I tend to hire people who don’t need a lot of management and don’t want a lot of management. So, boy I can identify with that.

Adam Moss: I actually think I was a good manager. But there came a point when I just couldn’t do it anymore. When it had so crowded out the other reasons why I had gone into journalism in the first place, that I just want to figure out a way to get back to that.

George Gendron: Well, unlike you, I can say unequivocally, I was not a good manager. And I have lots of people who will attest to that. So I hired a managing editor who was. And then I ended up marrying her.

Adam Moss: Oh, well that’s nice. What a lovely story.

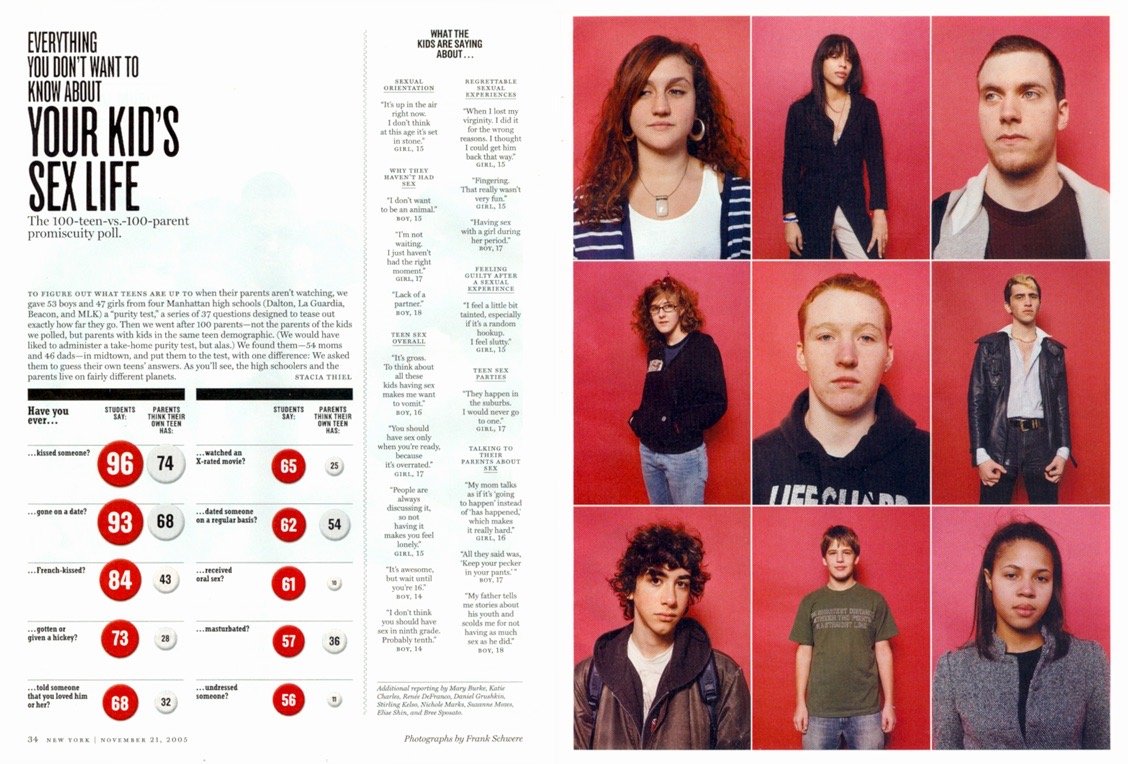

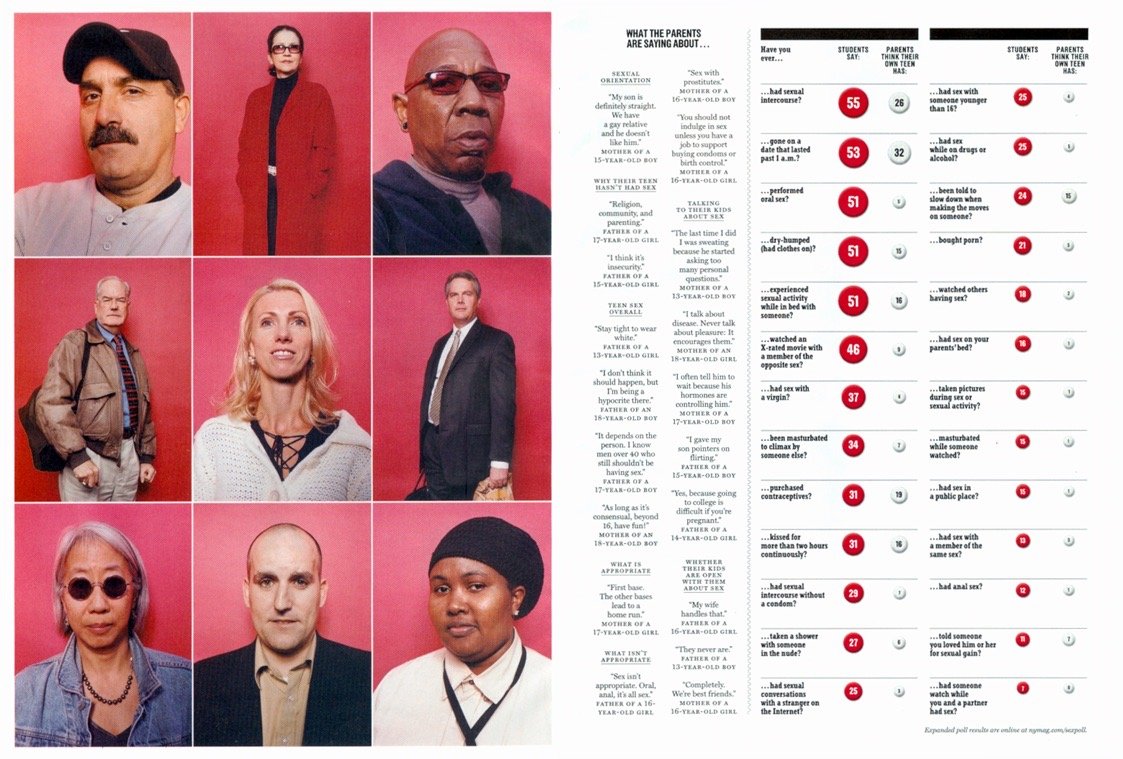

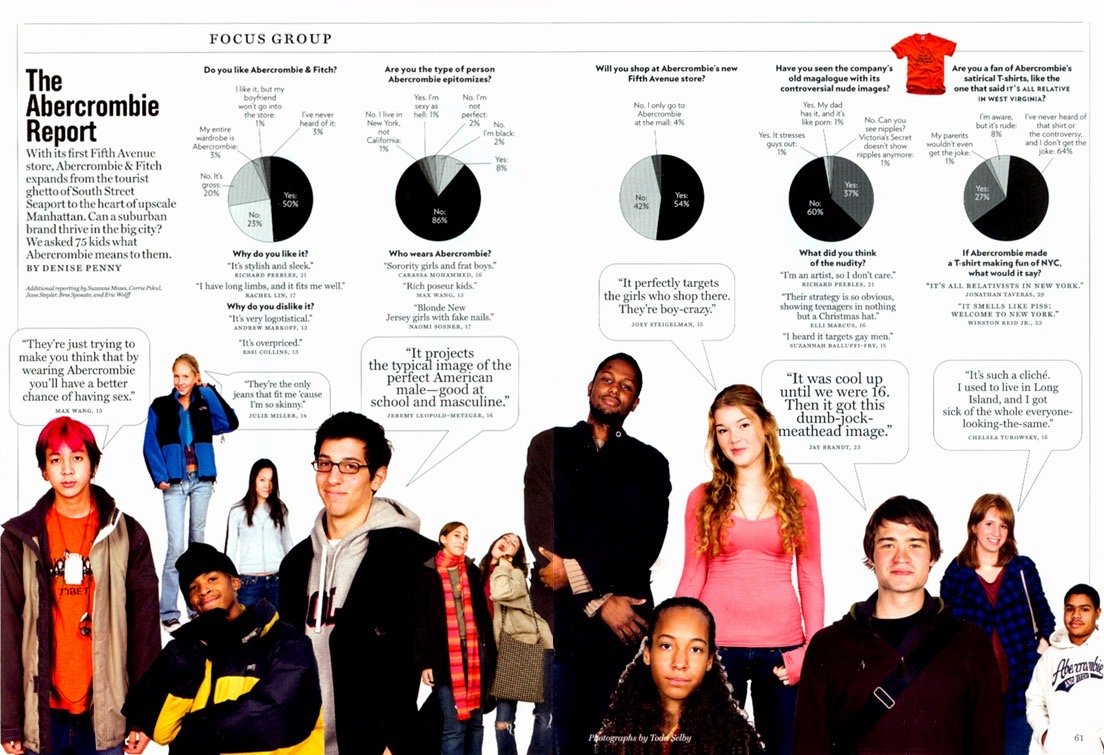

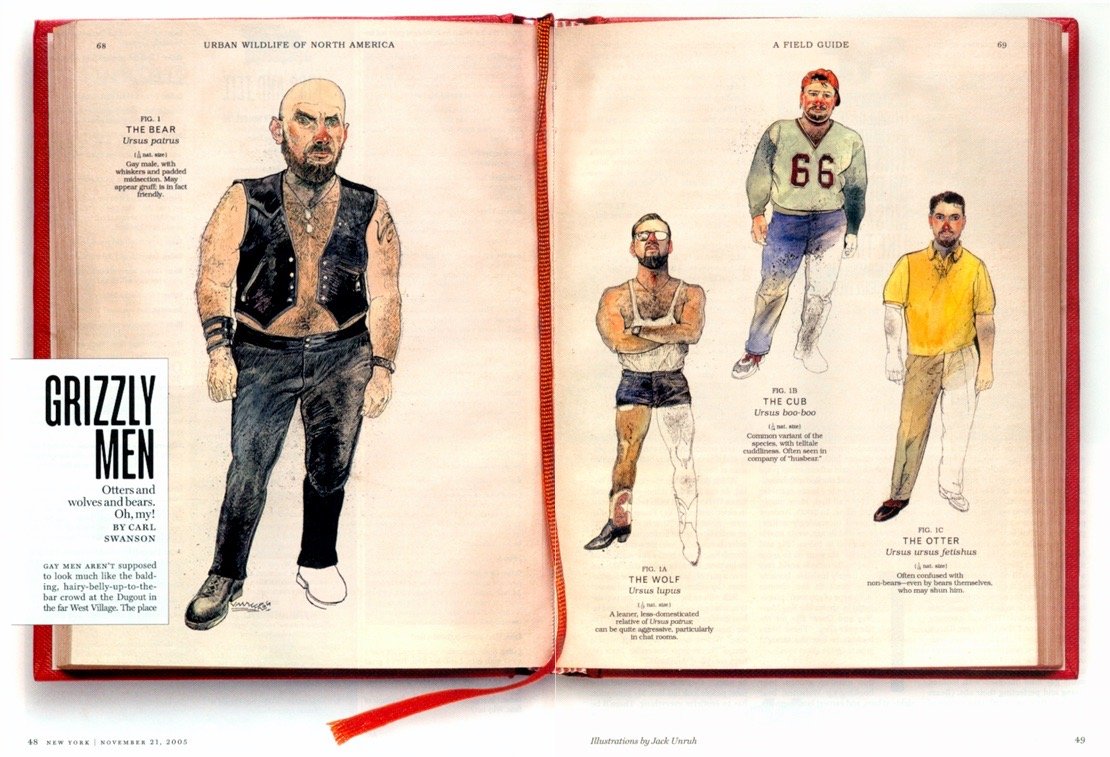

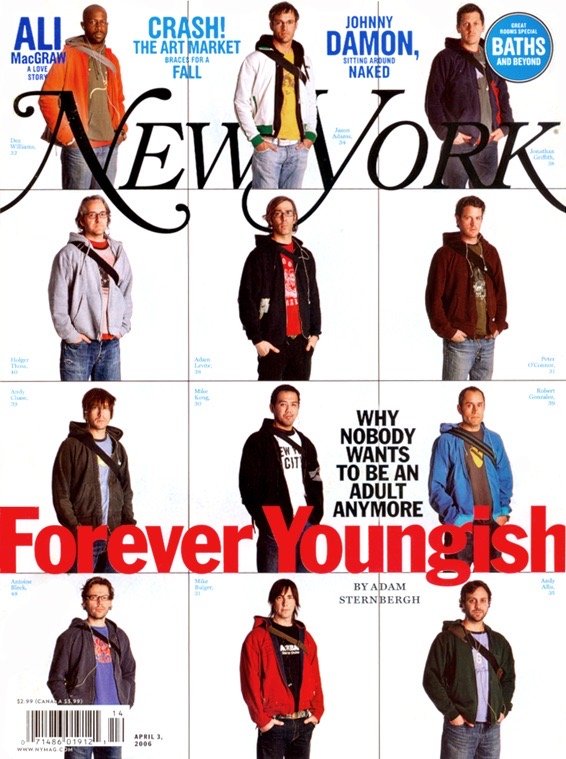

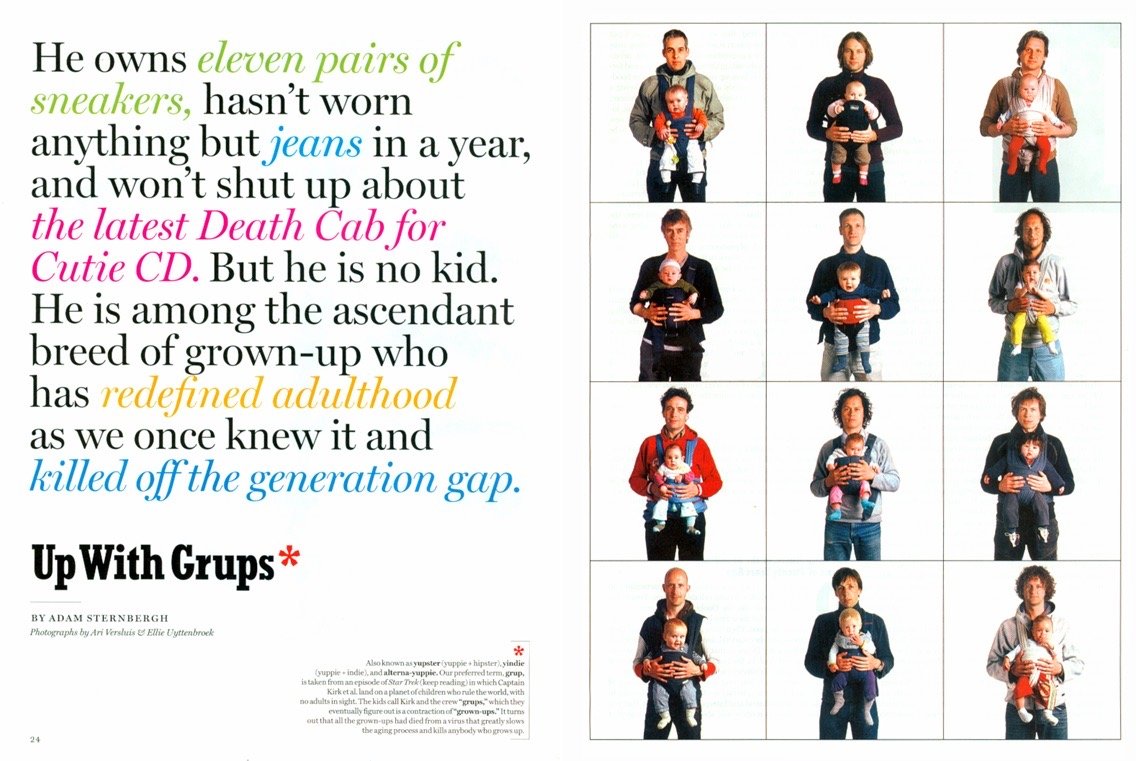

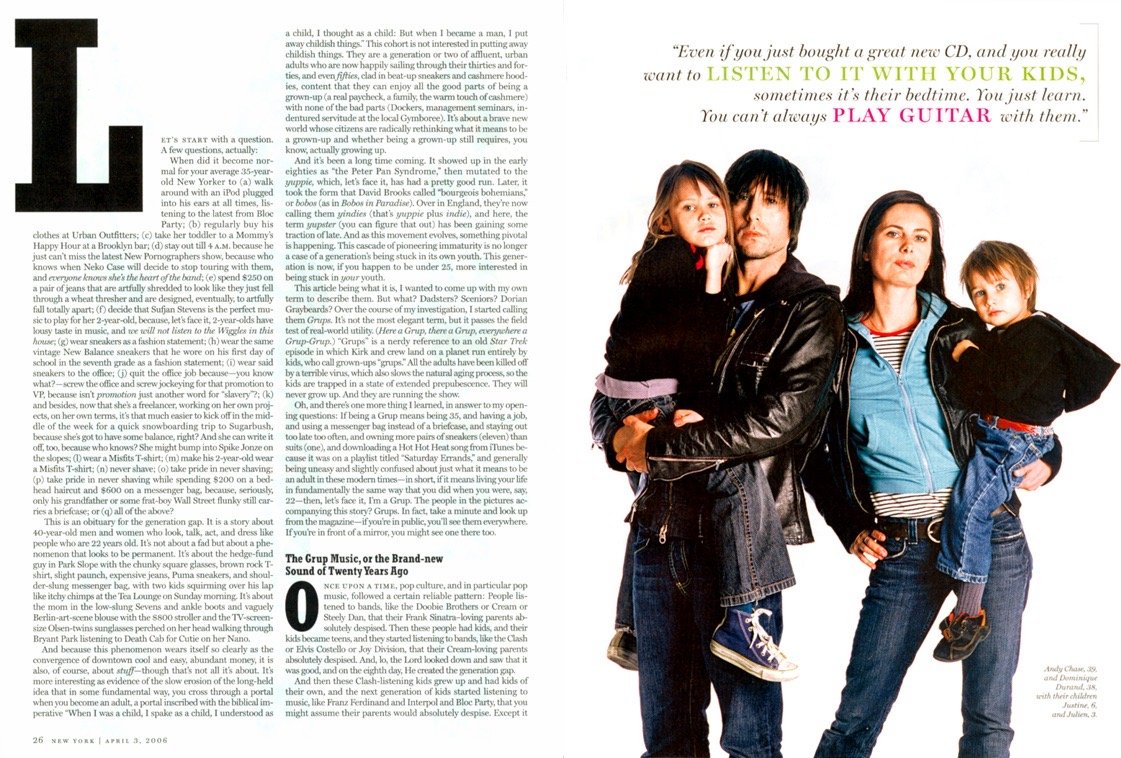

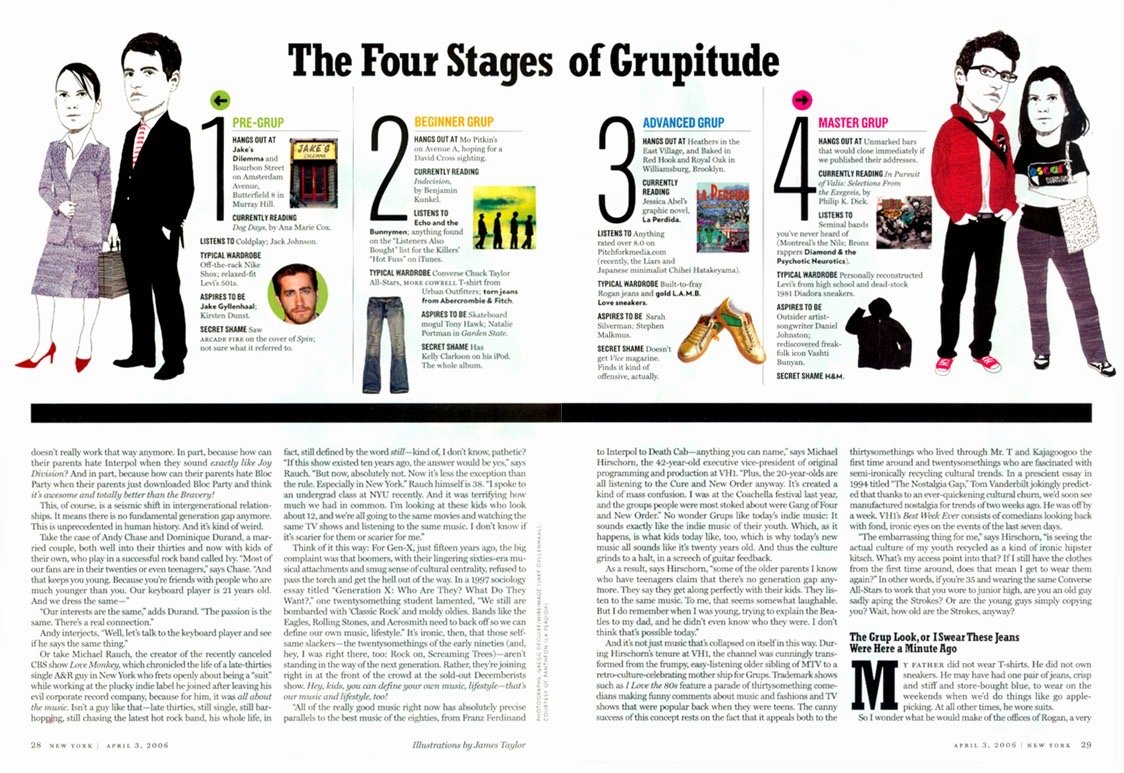

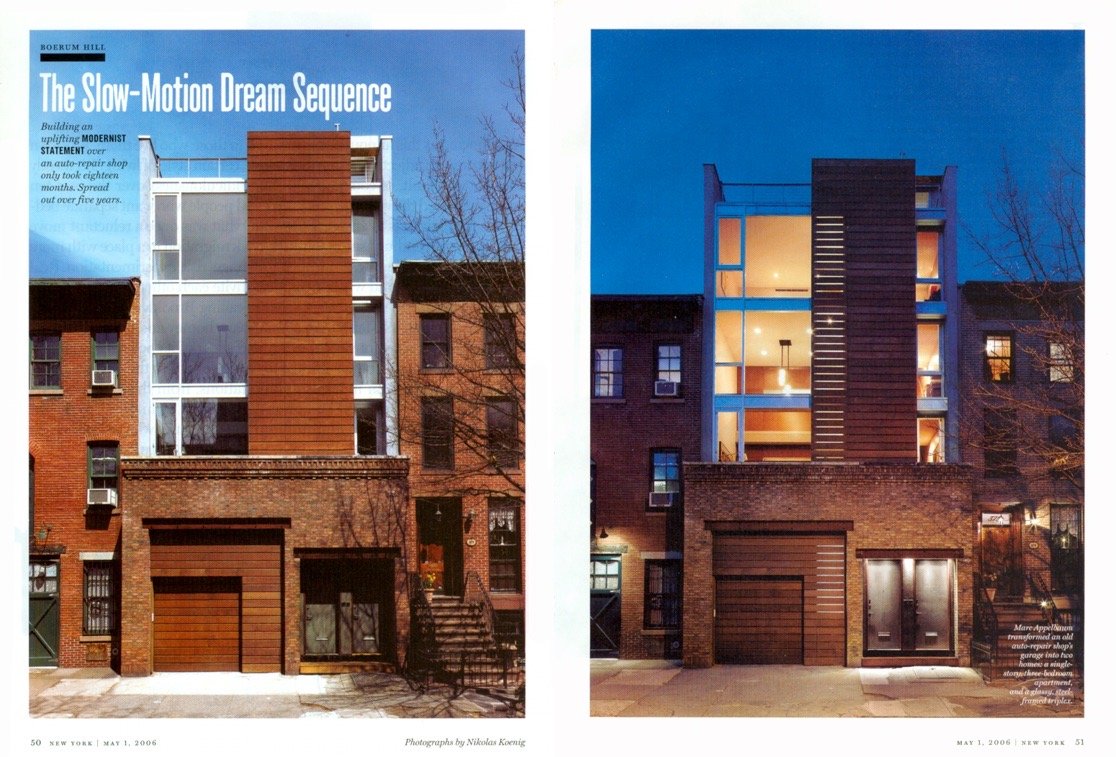

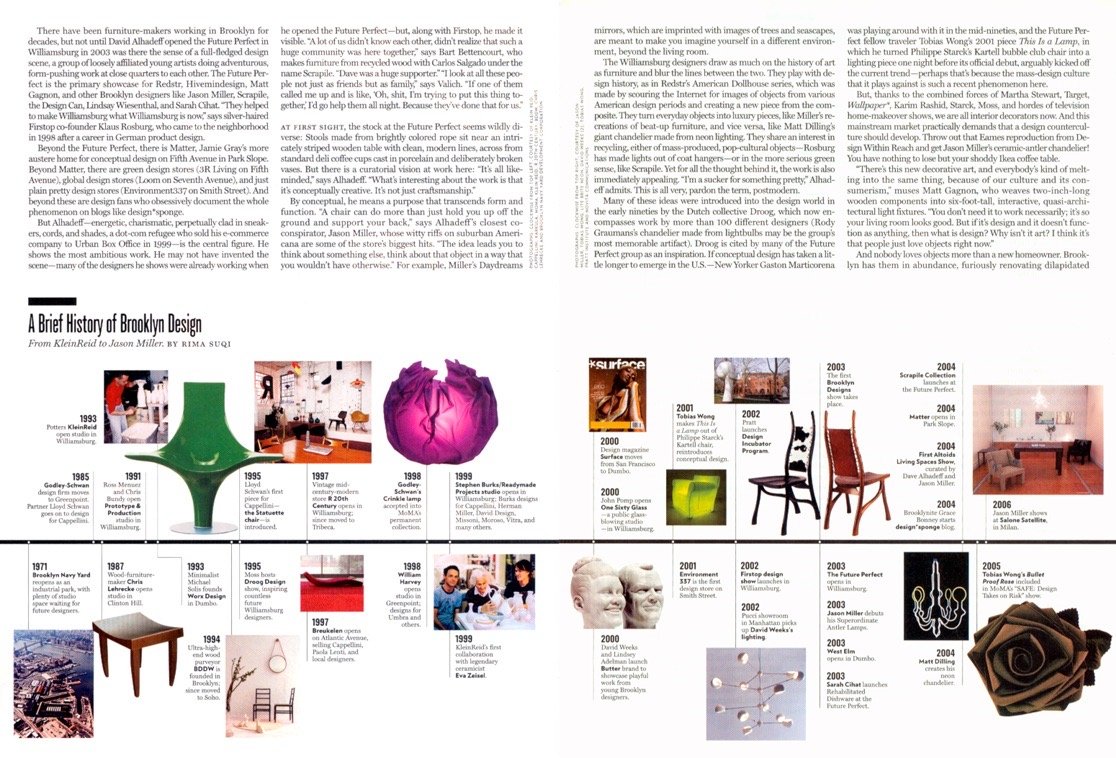

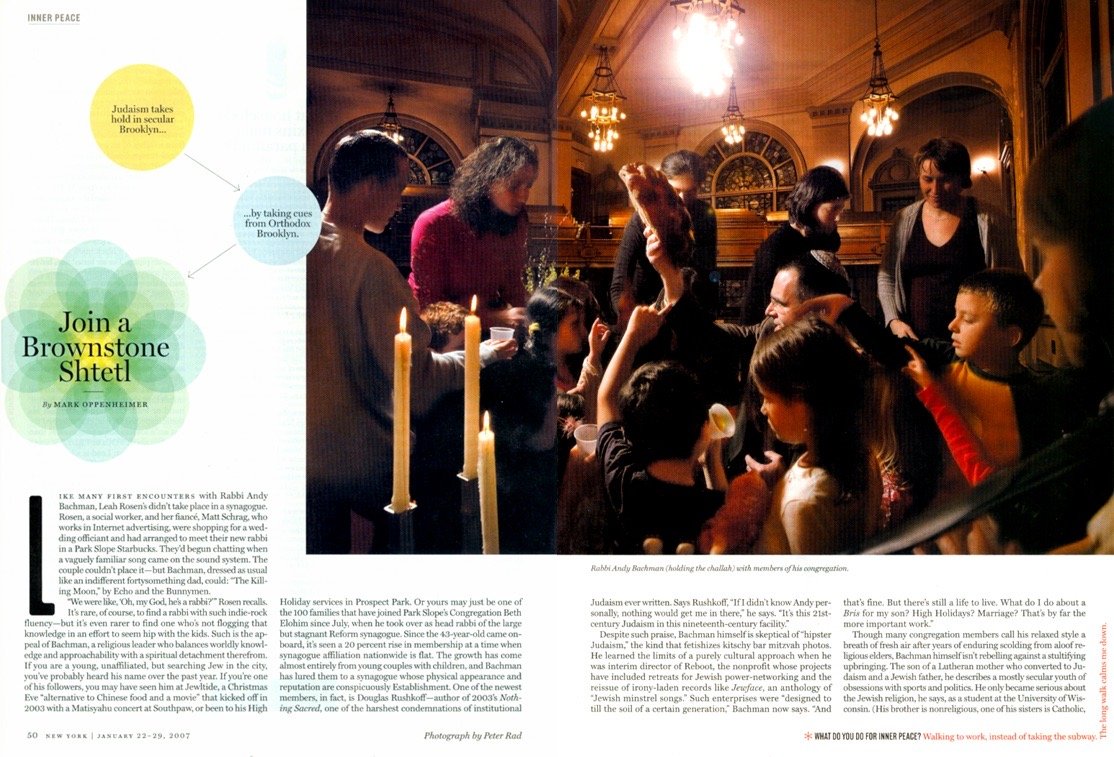

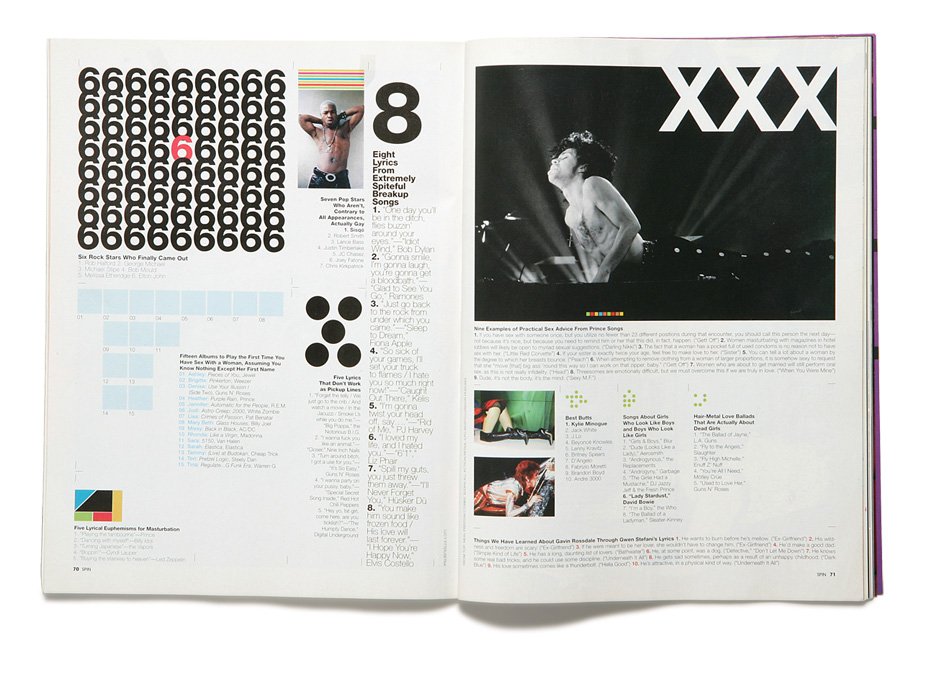

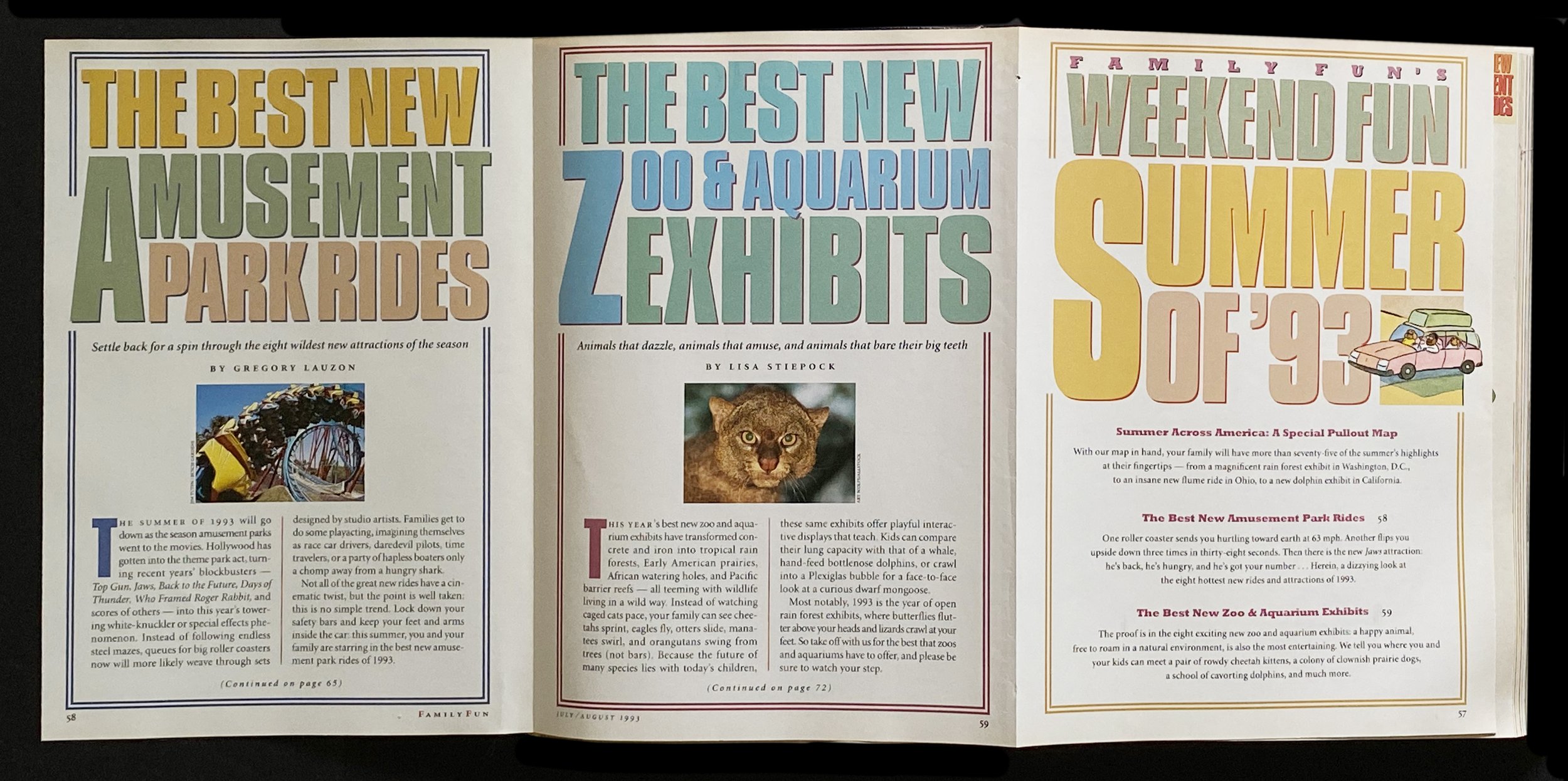

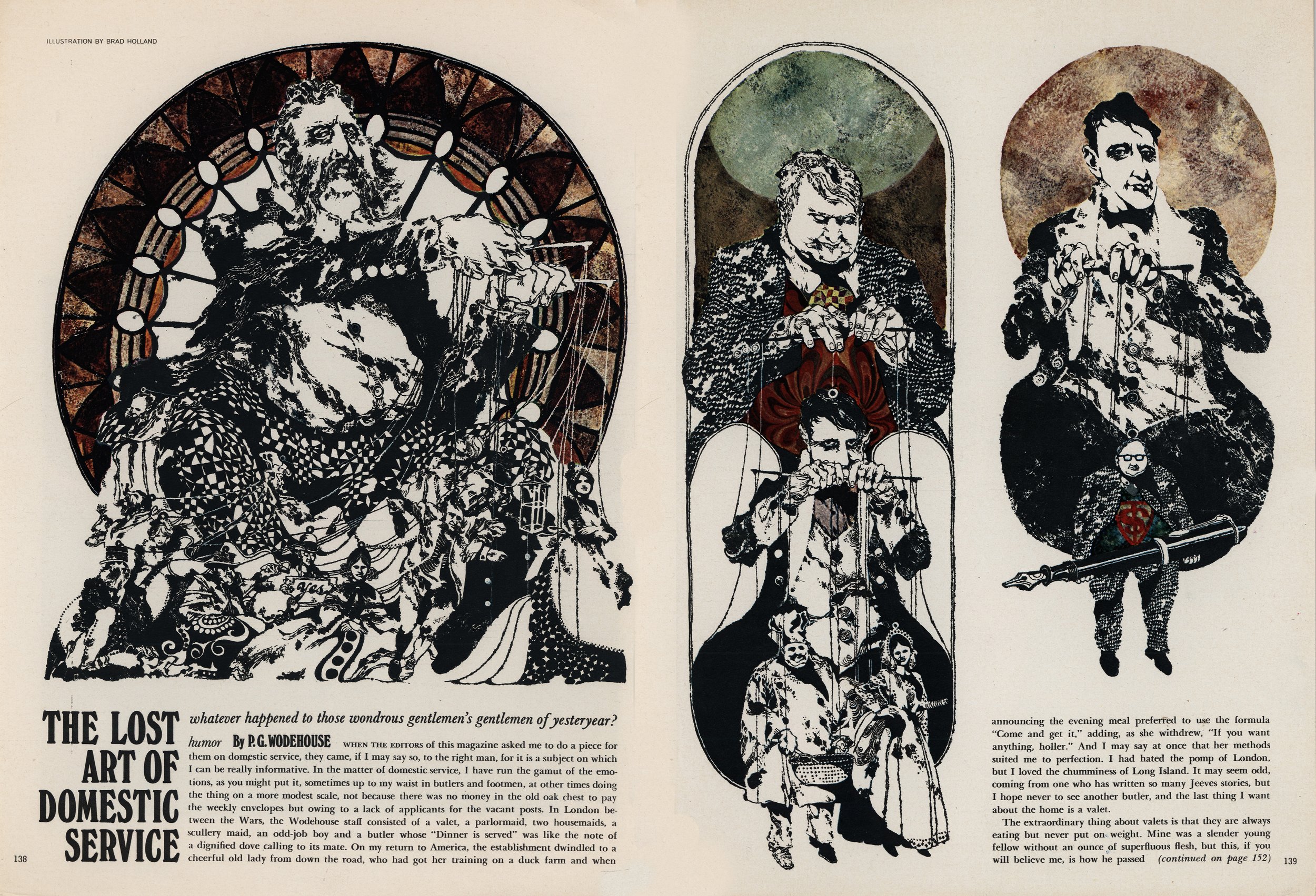

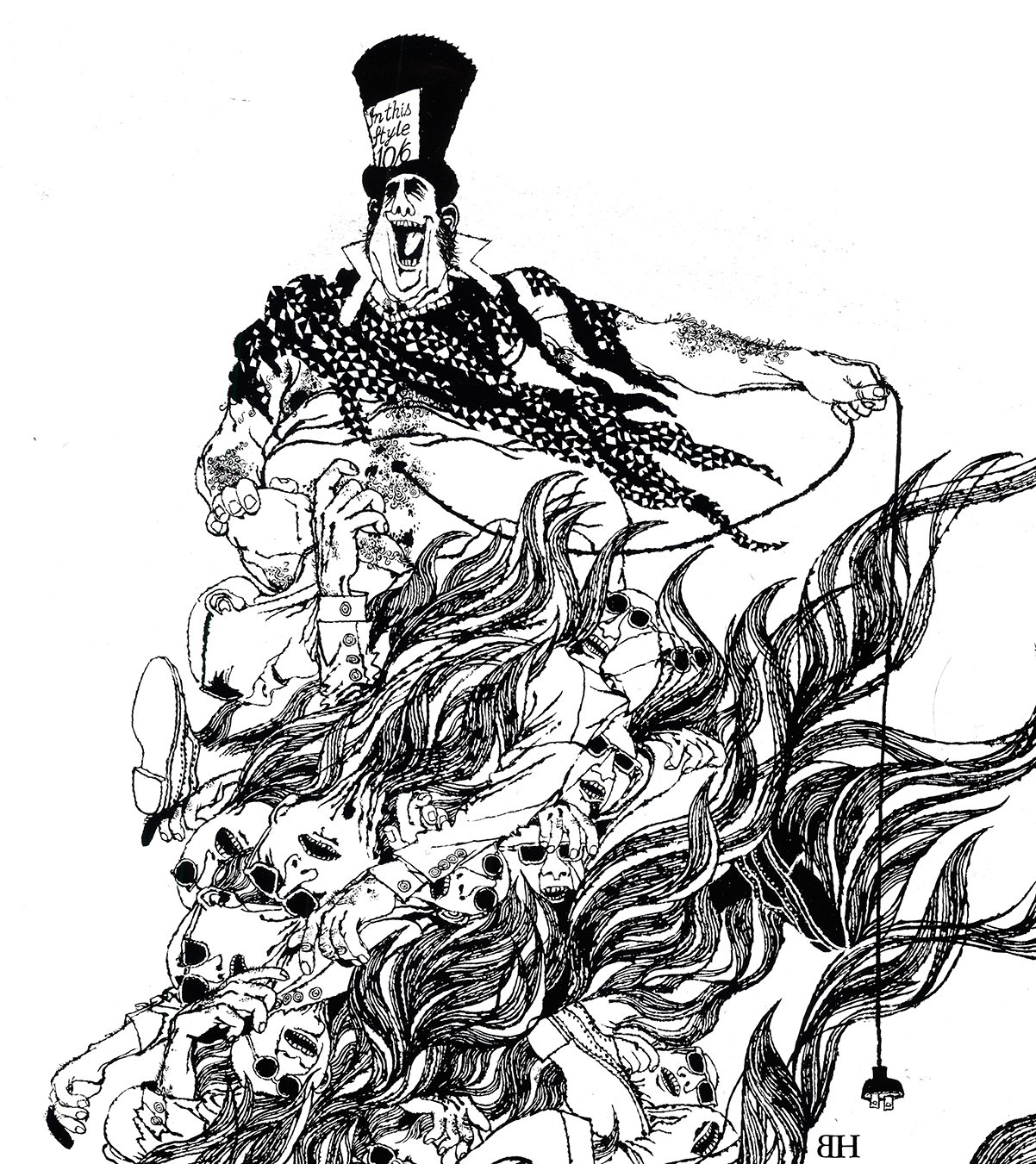

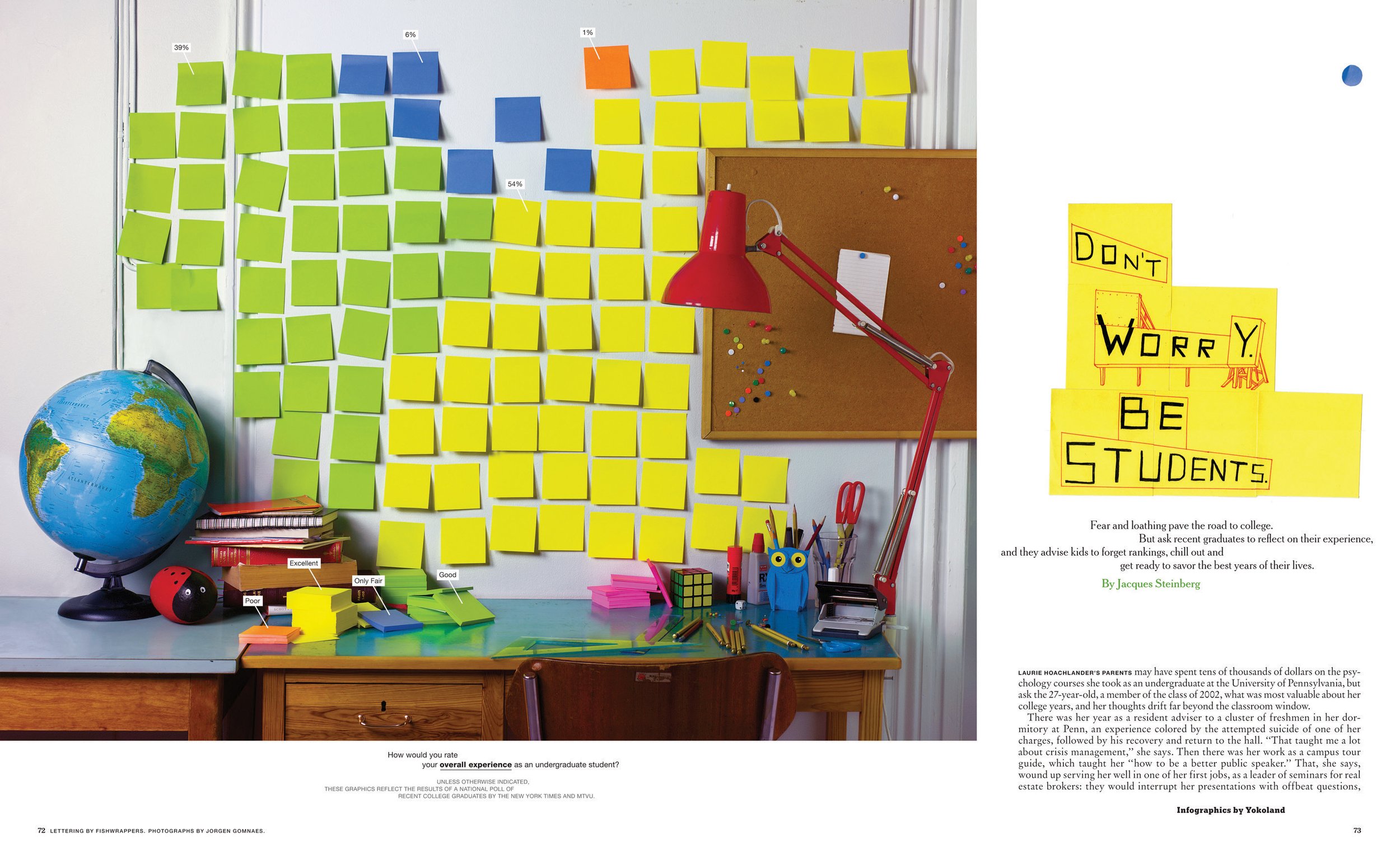

Moss and his team created several recurring packages like this 2005 one (above) on sex. In 2006 (below), Moss introduced the world to “Grups.”

“In journalism in general, the thing that I always liked the most was the inventing part.”

George Gendron: That was, yeah. So it’s interesting listening to you talk because we sold Inc. to Bertlesman in 2001. Boy were we lucky, because Bertlesman wasn’t publicly traded, it was an all cash deal. People talked about the deal and said, “Man, you guys were so smart strategically about when to sell.” No, we weren’t. We were just lucky. A year later, BusinessWeek was sold for a buck. But since then, I’ve never had a job. I’ve just worked on projects.

Adam Moss: Right.

George Gendron: And, on the one hand I love that. On the other hand, the one thing that I find challenging about it is often not having what I call an “anchor deal.” Does that make any sense to you?

Adam Moss: Sure. I’m going to be finished with this book soon, and I will lack an anchor. And we’ll see how that goes. When I left New York I did spend six months trying to figure out what I wanted to do. And then I very much needed something to do. I thought at first maybe I wouldn’t. Maybe I could just paint, which is what I do sometimes. But it turned out not to be enough. So, yeah, I missed that.

George Gendron: I got some really good advice after we sold Inc.: “Whatever you do, don’t do anything at all. Don’t do anything major for a year.” And on the one hand it was good advice. Don’t jump into things just to keep busy. On the other hand, six months through that year, one of my daughters came to me and said, “Would you do me a favor and go get a project, a big project?”

Adam Moss: Get out of my hair!

George Gendron: Yeah. It was kind of like that, and kind of moping around.

Adam Moss: I understand.

George Gendron: There’s a lot to parse there. So, you just said you painted.

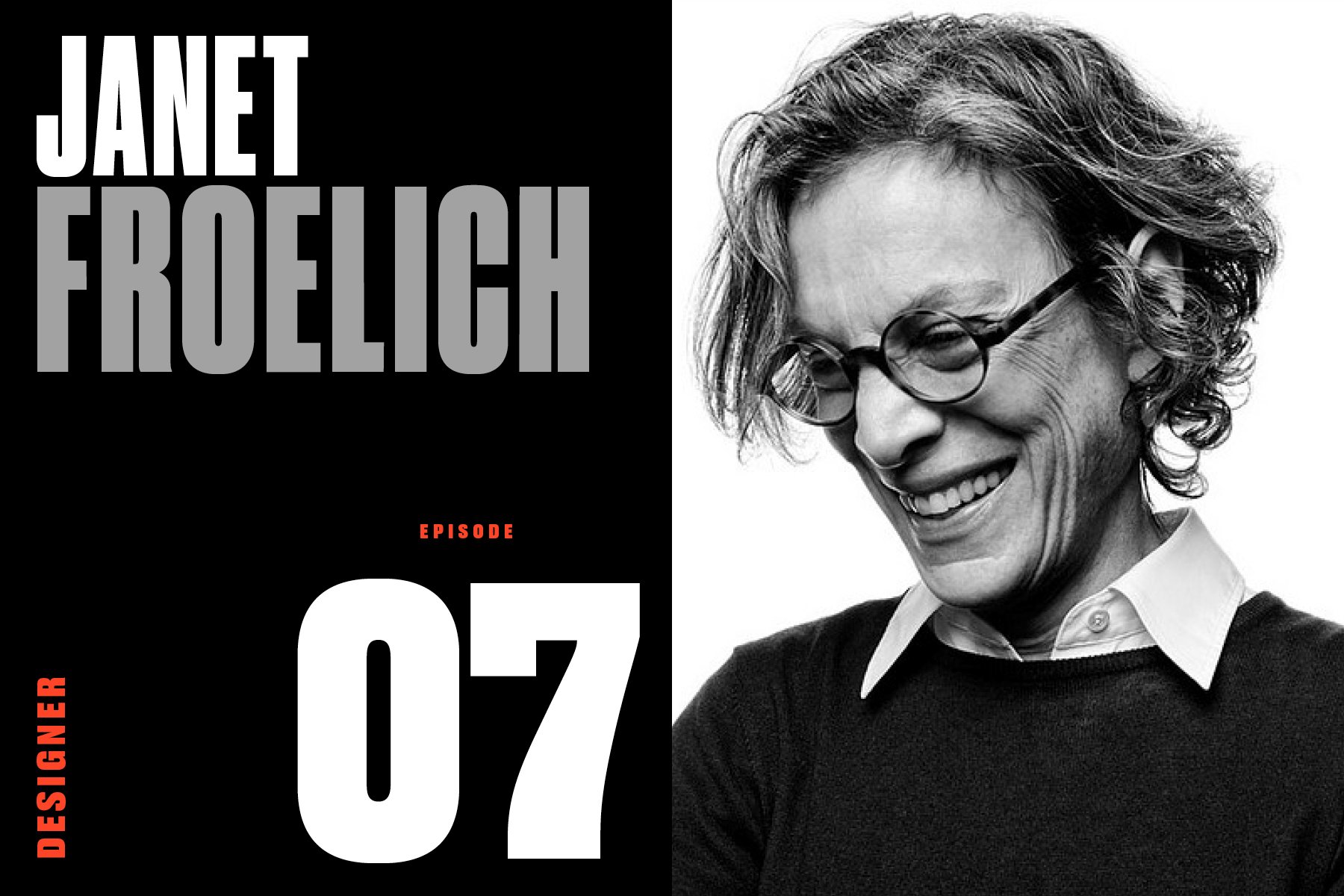

I was having a conversation recently with Janet Froelich, your former colleague, and she said, “Yeah. I’ve heard that Adam’s painting.”

Adam Moss: I really enjoy it, most of the time, when I’m not actually putting pressure on myself to paint well. Which is like a trick you have to play. It’s very hard to let go of the idea that you have to actually be good at it.

George Gendron: That is, isn’t it?

Adam Moss: Yeah.

George Gendron: Anyway, she said, “The trick I’ve learned is to do pottery. Because it’s unbelievably difficult. So difficult that I don’t have any illusions about ever being good at it.”

Adam Moss: Yeah.

George Gendron: “...But I love it. It’s like therapy. It’s like meditation for me.”

Adam Moss: Well, I think the meditation thing is really relevant to my love of painting. I’m sure pottery’s even more difficult, but I find painting very hard and very consuming. The amount of focus you need to paint well. I mainly paint figures. Sort of abstracted figures. And you just have to be all there.