What’s Red and Yellow and Orange All Over?

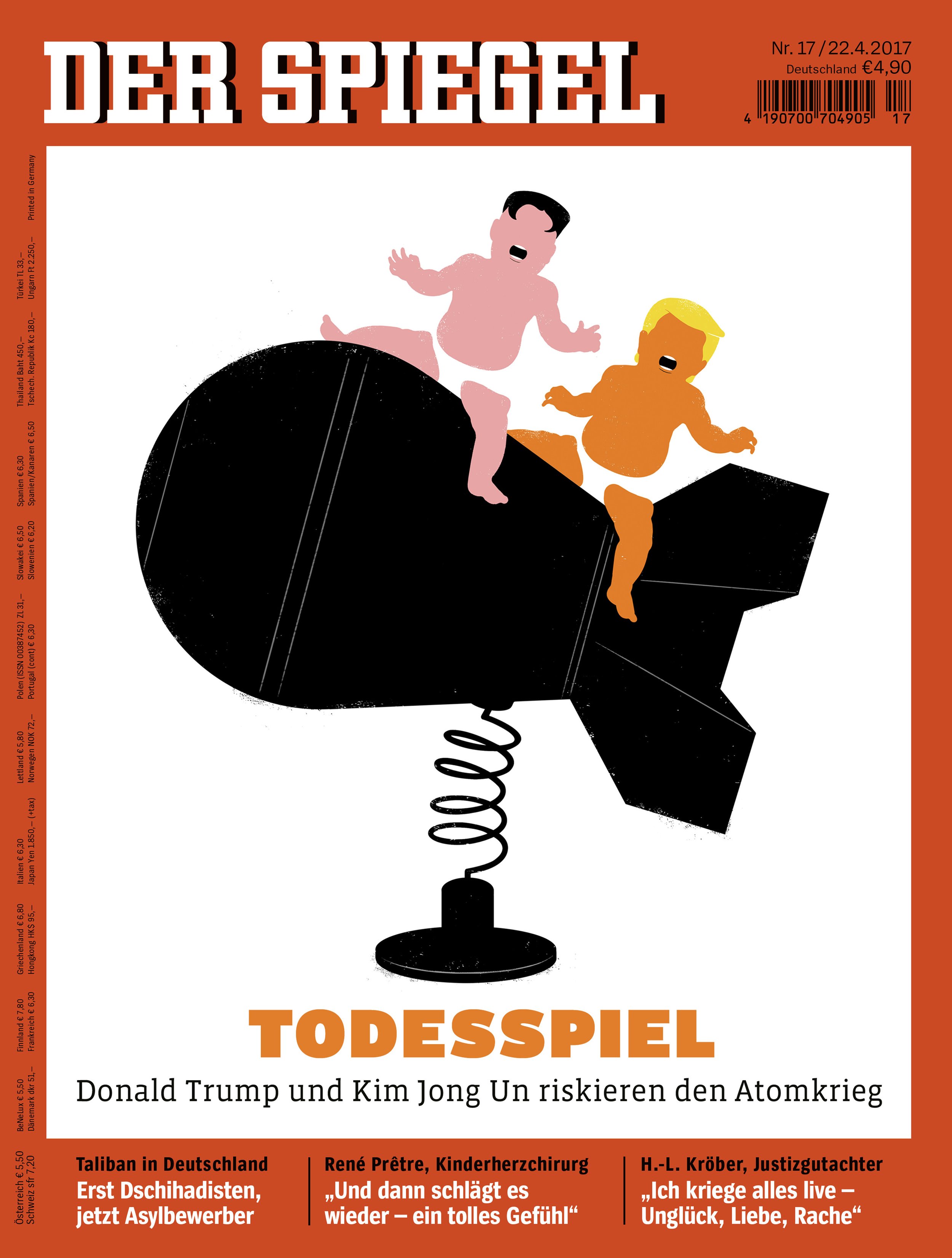

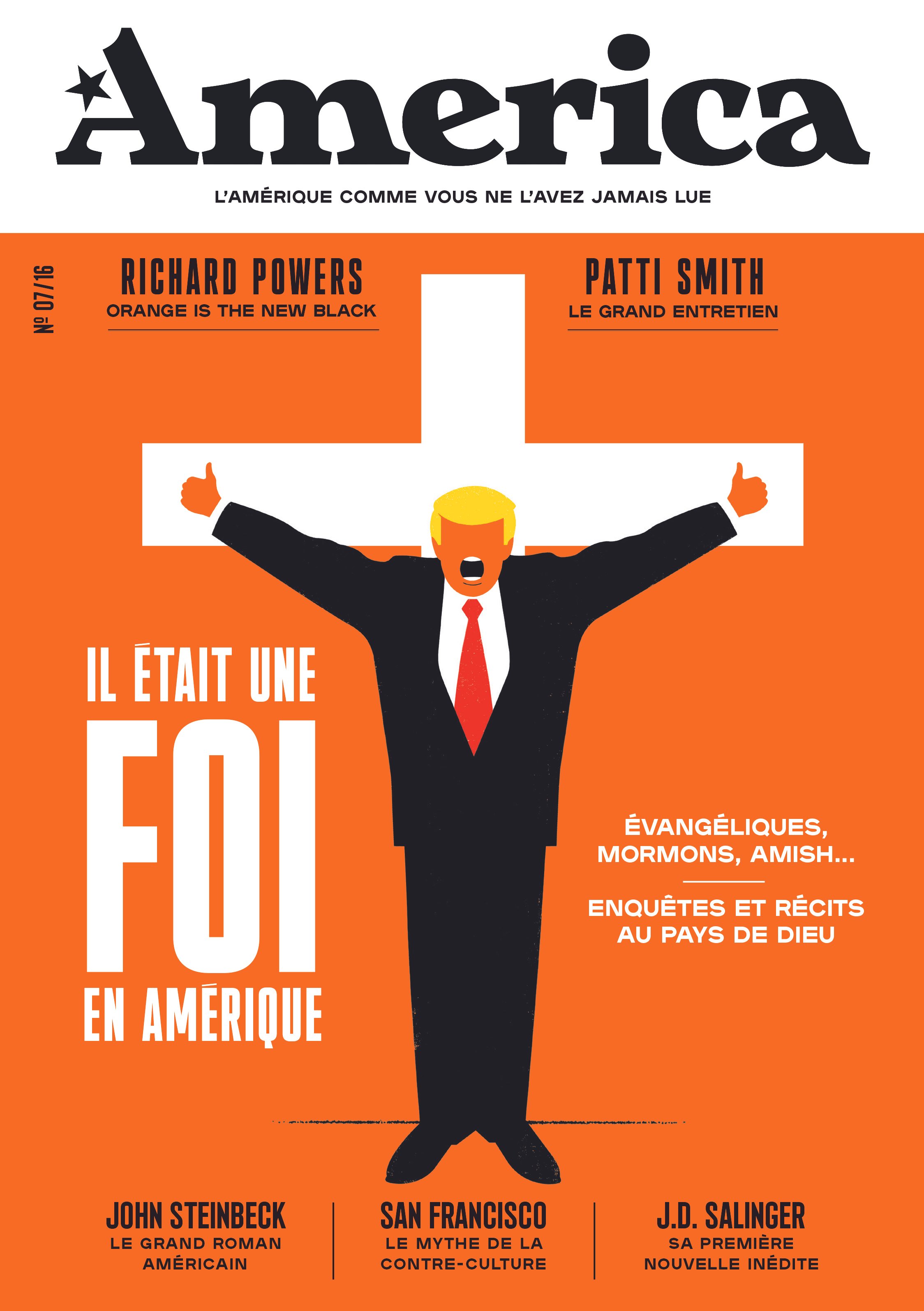

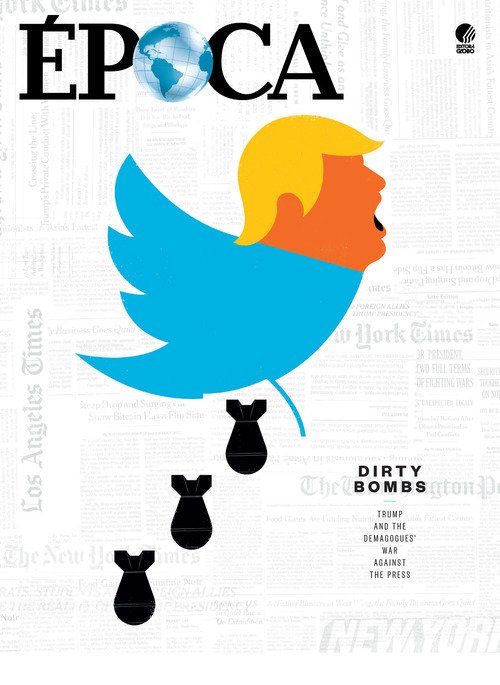

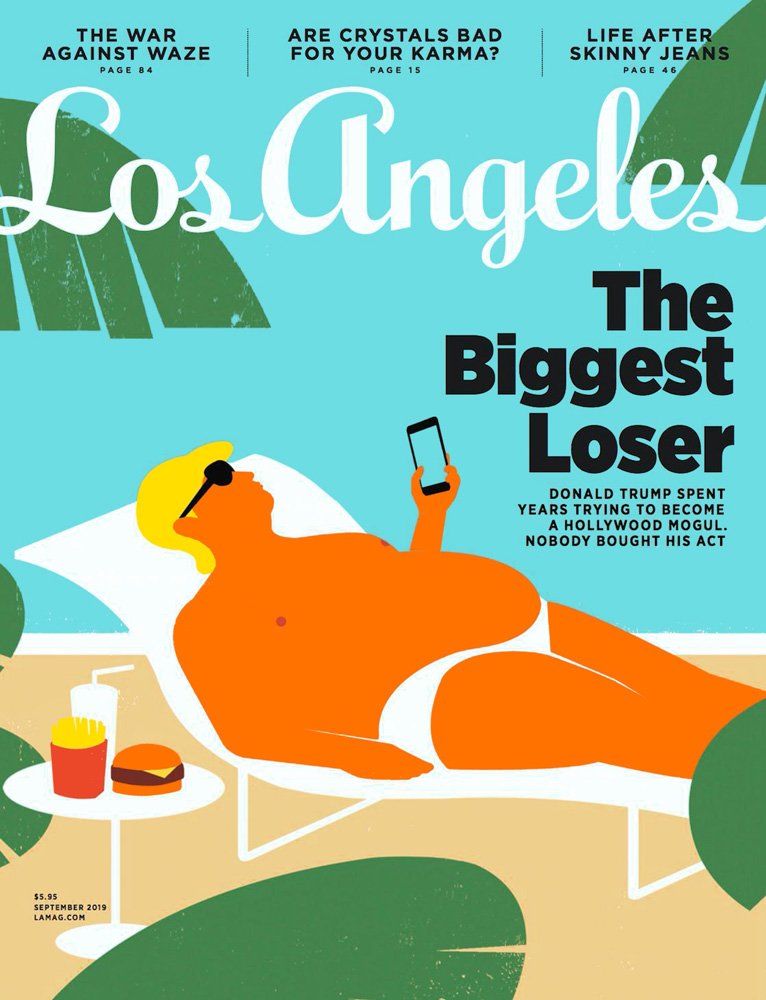

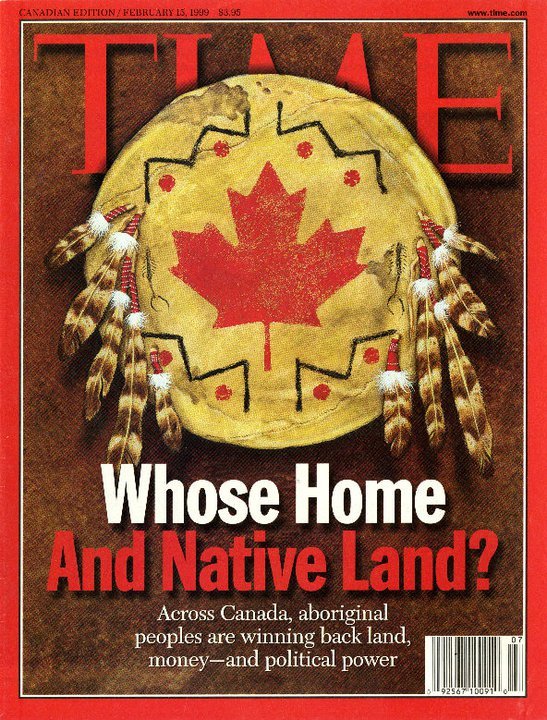

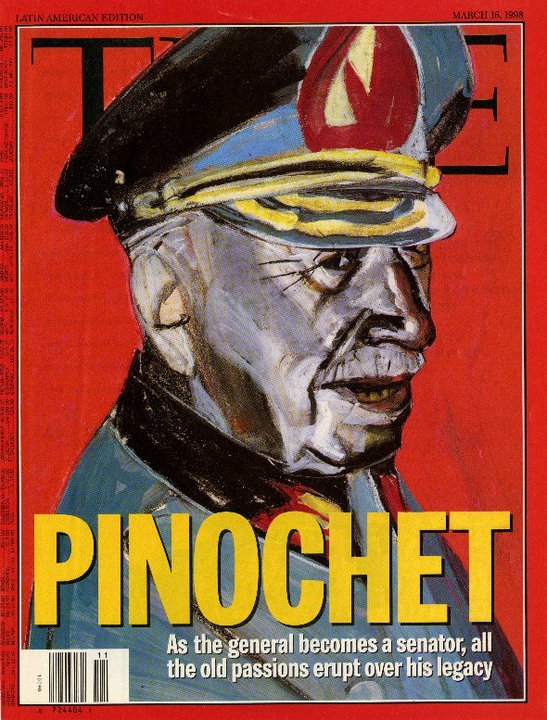

A conversation with author and illustrator Edel Rodriguez (Time, Mother Jones, Der Spiegel, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE , COMMERCIAL TYPE, and LANE PRESS

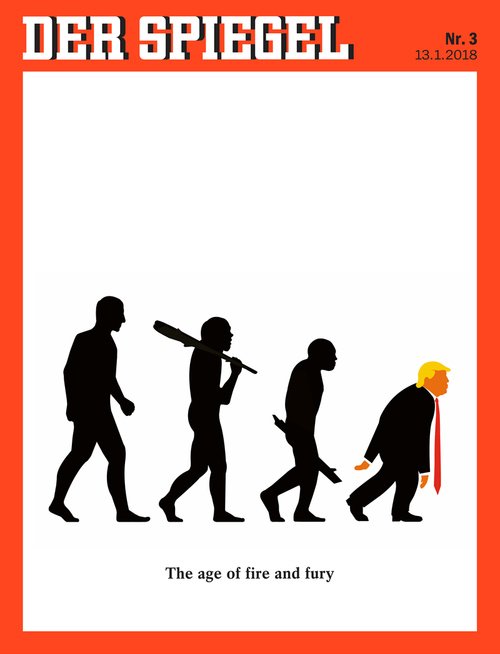

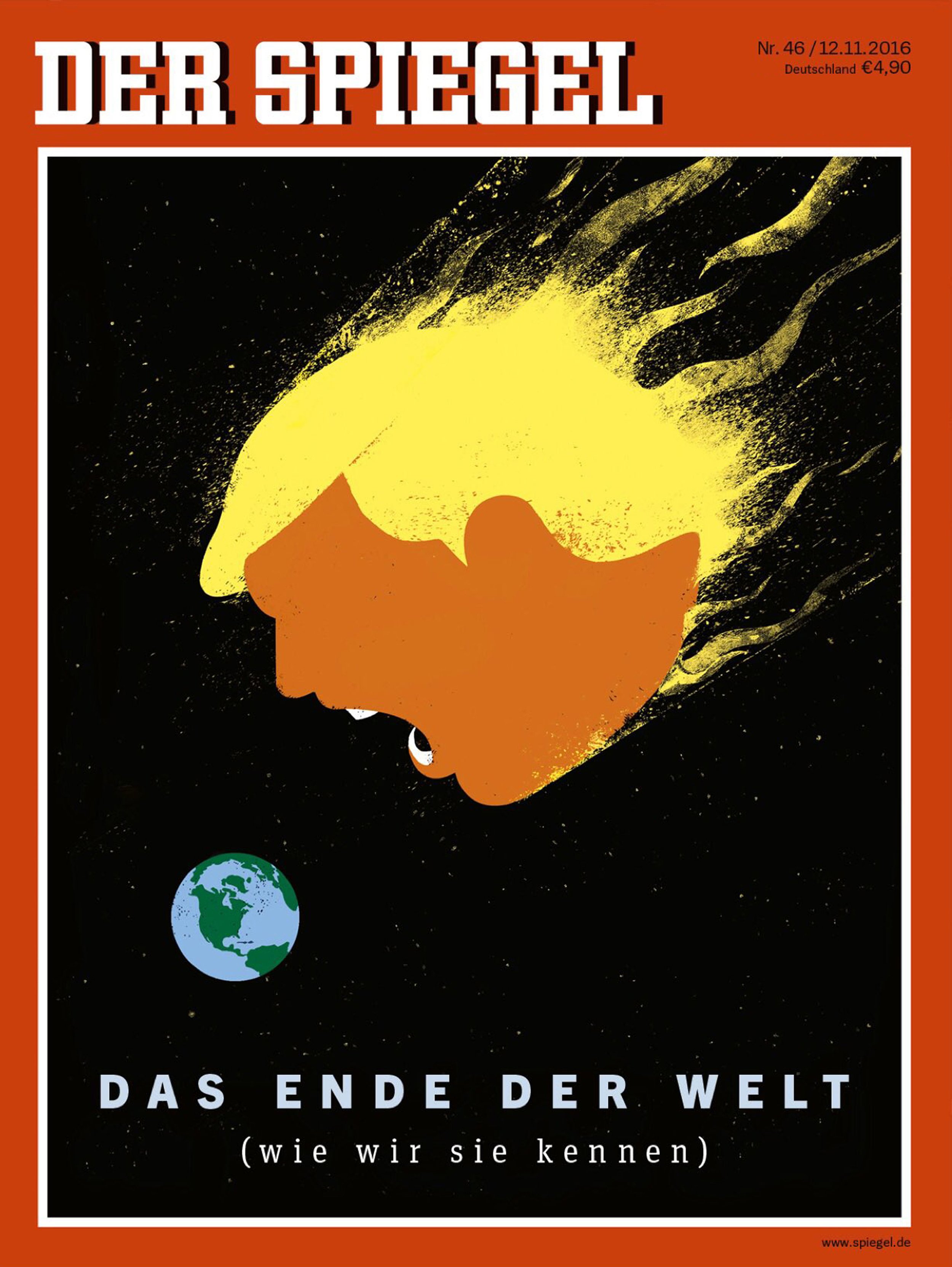

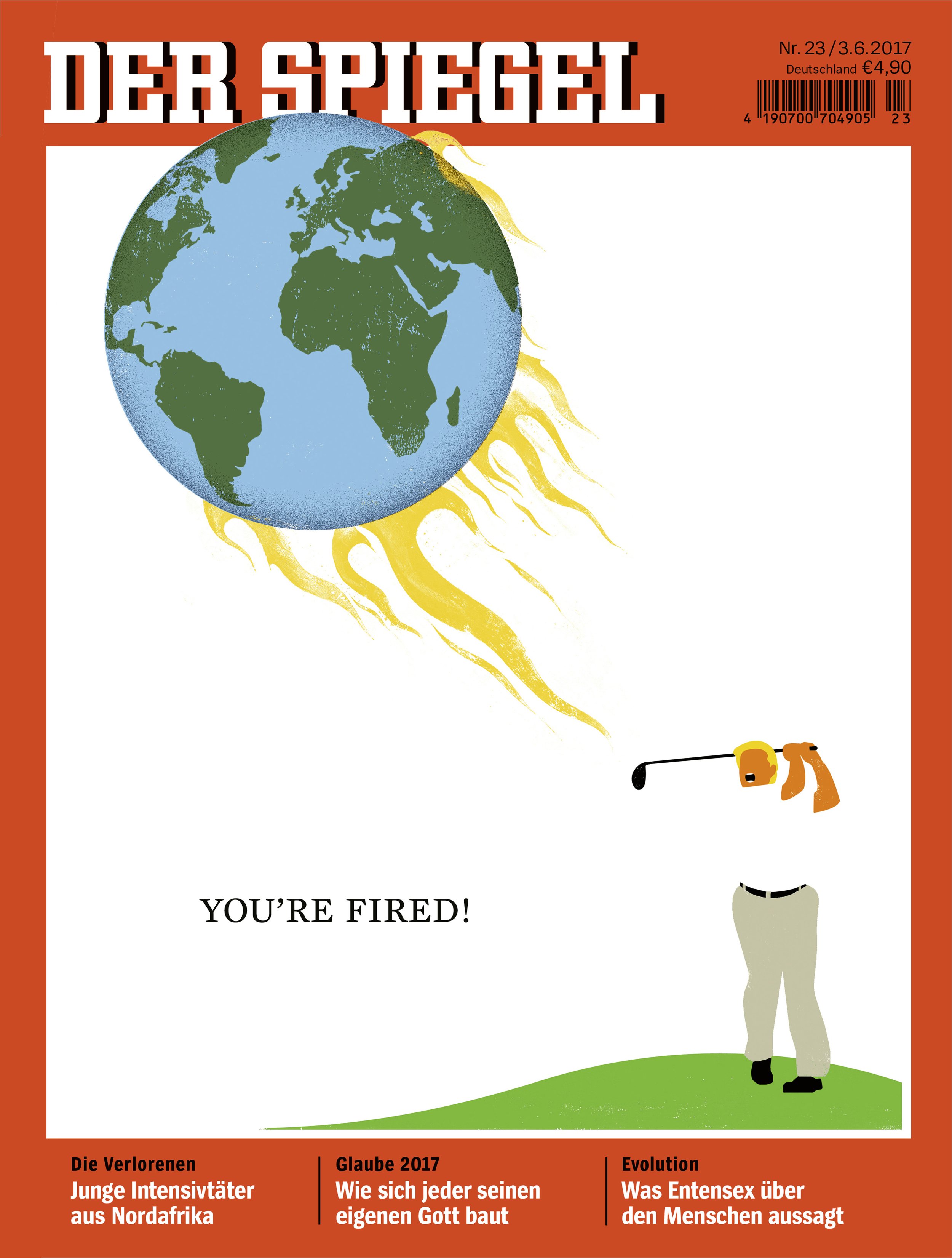

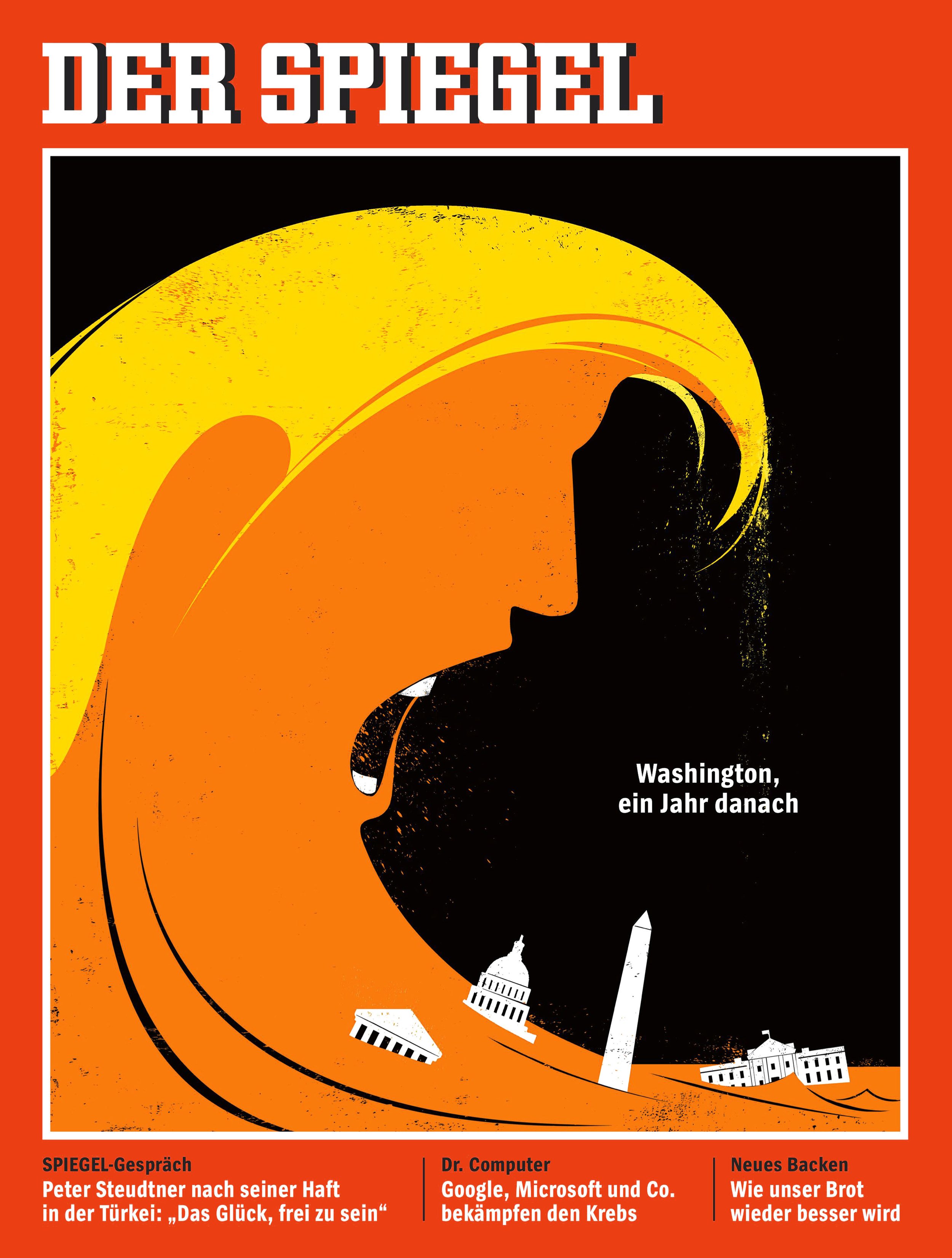

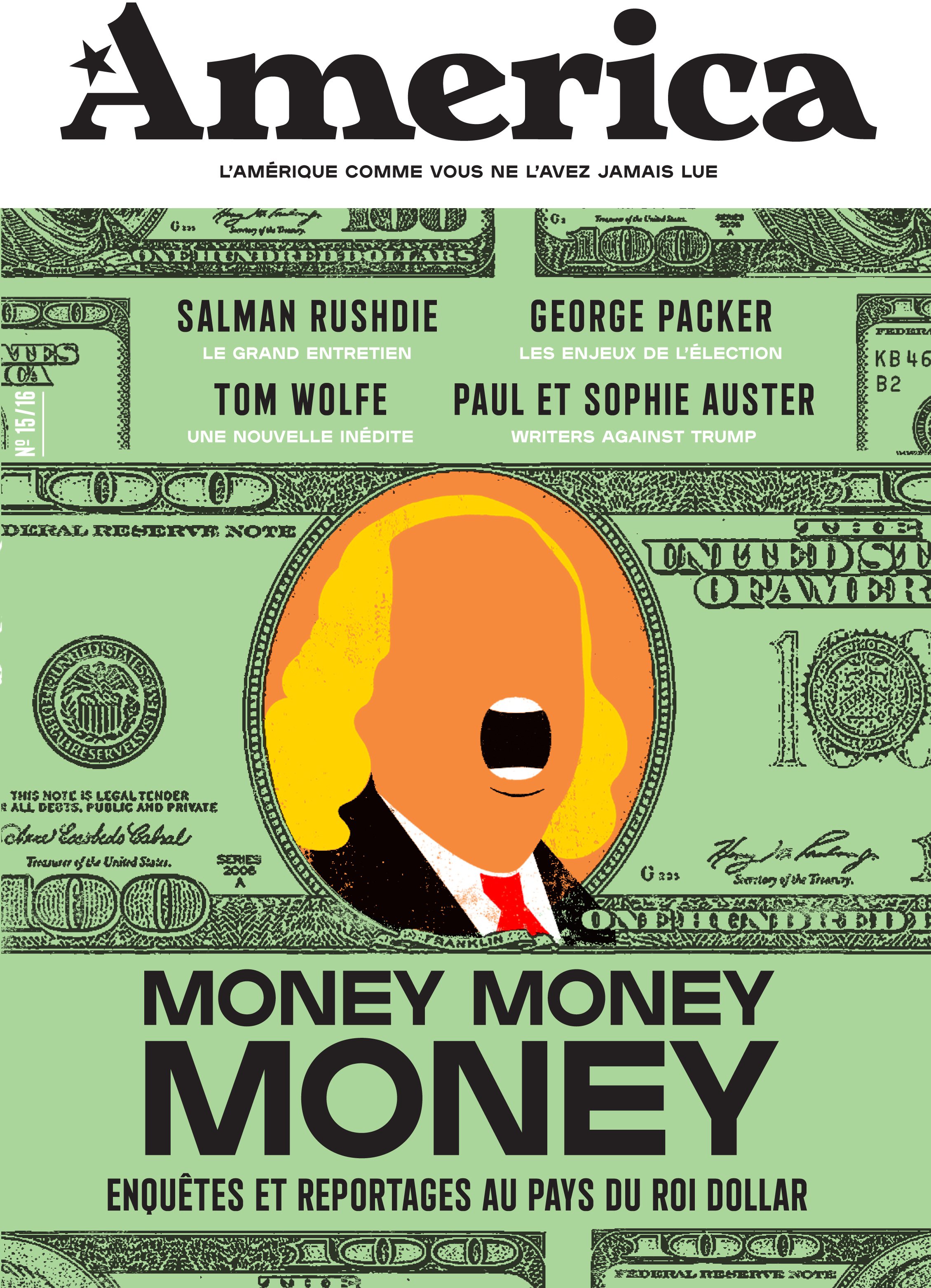

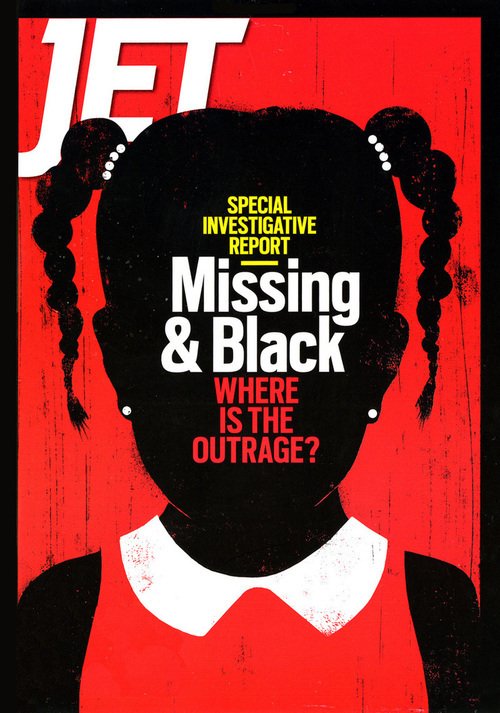

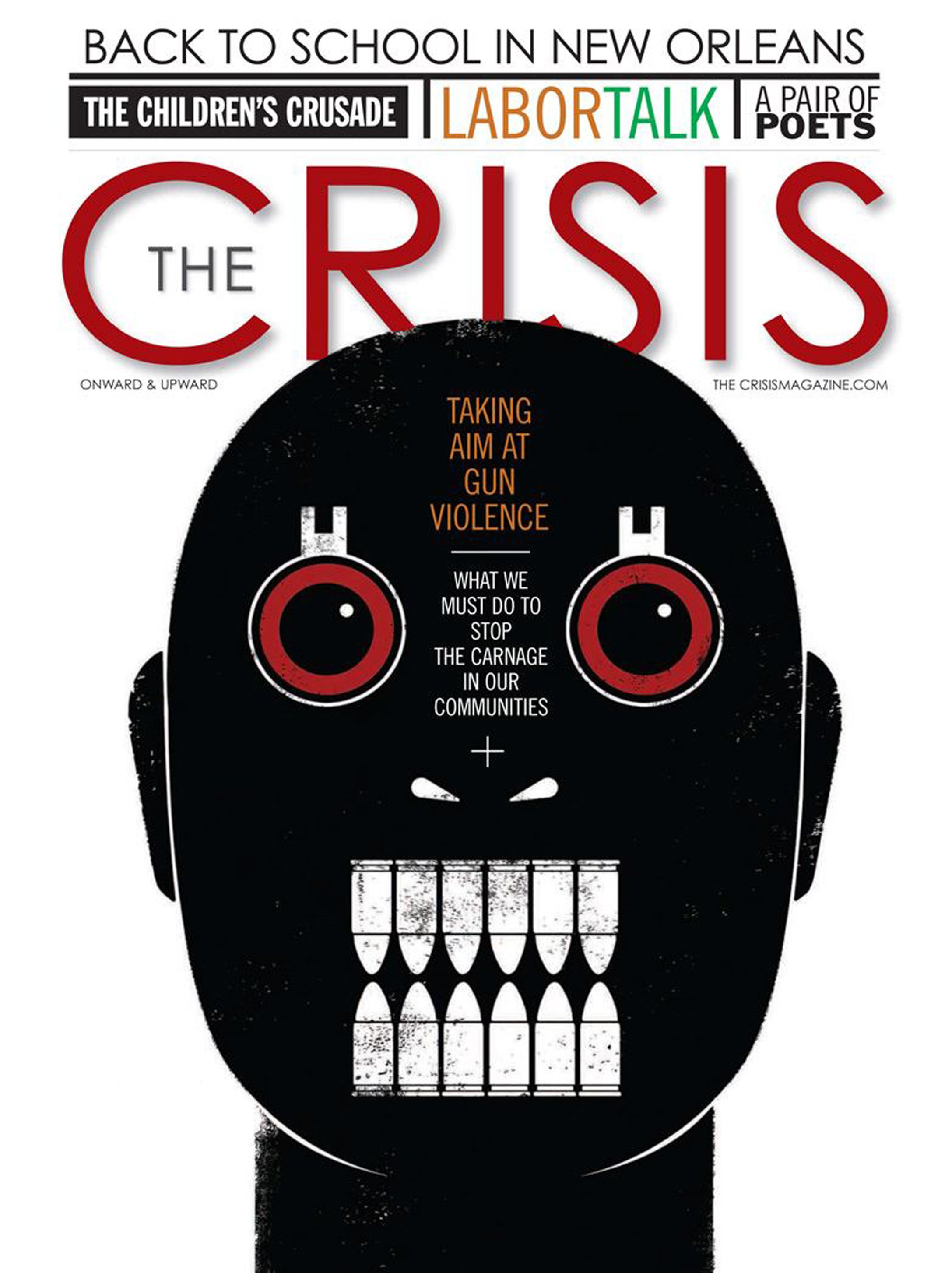

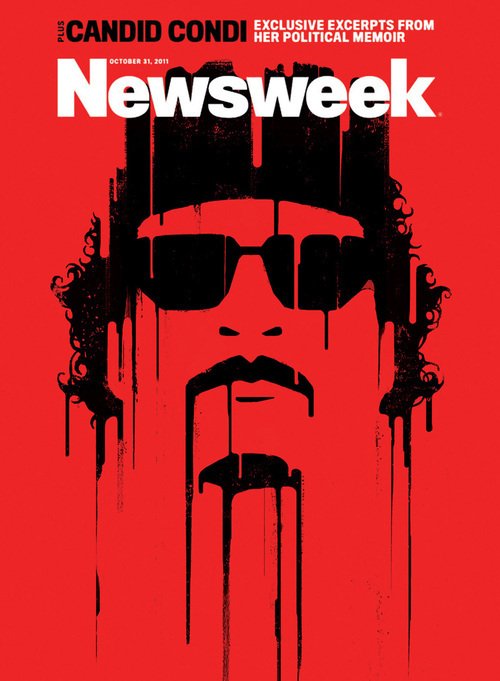

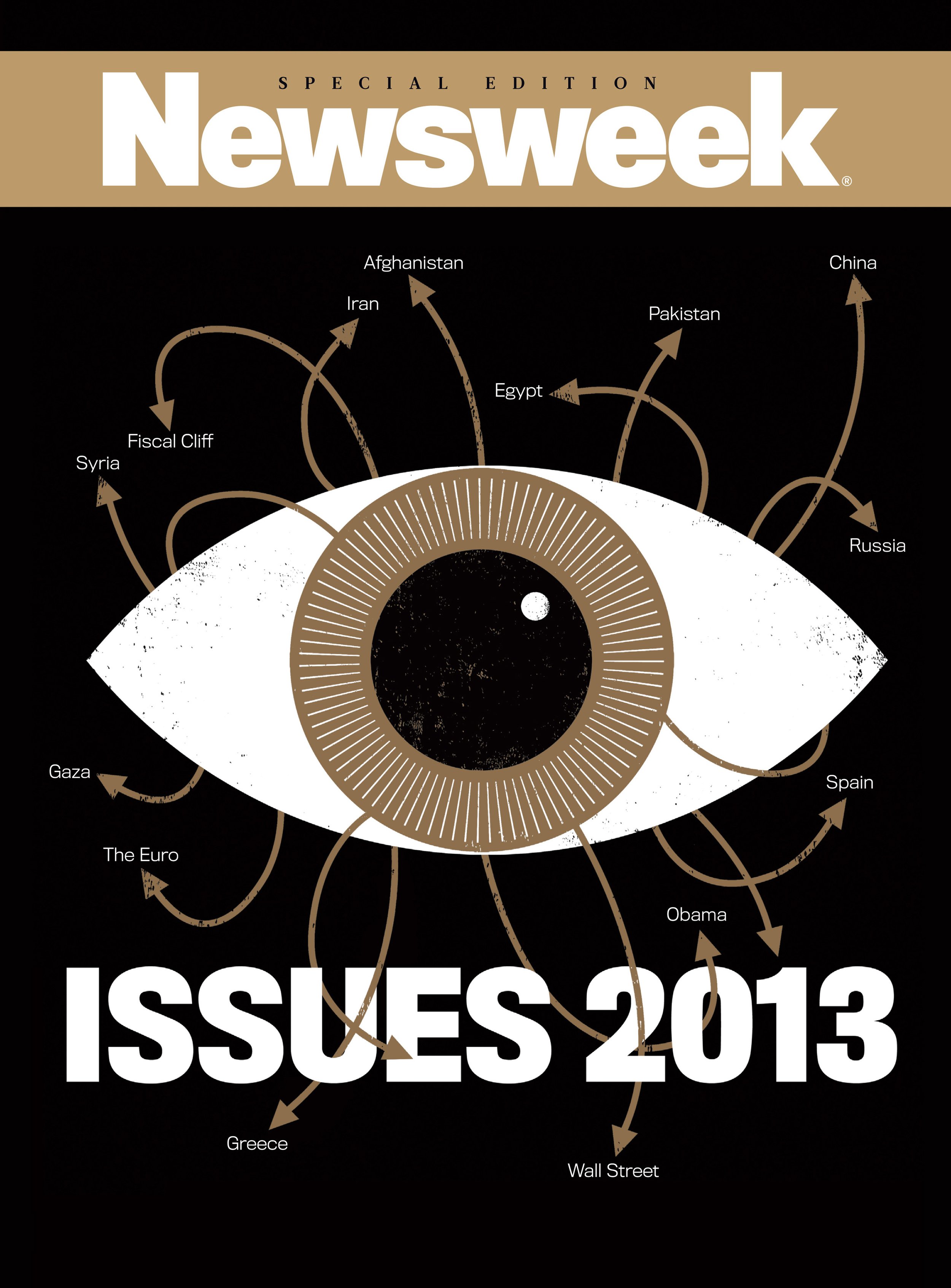

The images are iconic. And you know who they depict. They may be the most unforgettable magazine covers to emerge from the chaos of the late 2010s. Why are they so effective? Because of the implicit understanding of what’s being said between artist and audience—without a word being spoken. Using just three basic colors, today’s guest has created the brand identity of resistance.

Edel Rodriguez was born in Cuba, and though he left that island nation when he was quite young, arriving in the US during the Mariel boatlift, one can’t help sensing an aesthetic that might be especially Cuban, or can be called, perhaps, “authoritarian-adjacent.” Because when the US flirted with—as it will again this year—a presidential candidate rotten with autocratic tendencies, Rodriguez’s imagery is the perfect match for the moment.

His red, yellow, and orange covers for Time, Mother Jones, and Der Spiegel—25 in all—were minimalist, dangerous, and dead-on-balls accurate. And he joins us today fresh off the premiere of his stunning graphic memoir, Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey.

Of his notorious subject, Rodriguez saw the famously orange skin tone as a “warning sign,” he told Fast Company, and the simple style he employed resonated because it broke through the noise in the most effective way imaginable. Coming from Cuba, Rodriguez feels a duty to express, through his art, the potential outcomes of the choices we have made—and might make yet again. As he told The Guardian, “I don’t think most Americans realize what a coup is.”

Of course, Rodriguez is more than just this one subject. But he’d be the first one to admit that he is political, and he makes no pretense of hiding his politics. As for his fans, they tell the artist that his work helps them crystallize their own thoughts and animates their feelings in ways they struggle to express on their own. A picture is worth a thousand words, indeed.

George Gendron: Now, if you’ve ever heard our podcasts we usually don’t talk politics here, but I’ve got to ask you, given your reputation, who did you vote for in the last election?

Edel Rodriguez: The last American election? Yeah. I pretty much voted for the entire Democrat party for a long time. Yeah, if that’s not clear enough. There’s basically one party that’s gone insane and another party that is just trying to manage the place. And so I just vote for that party.

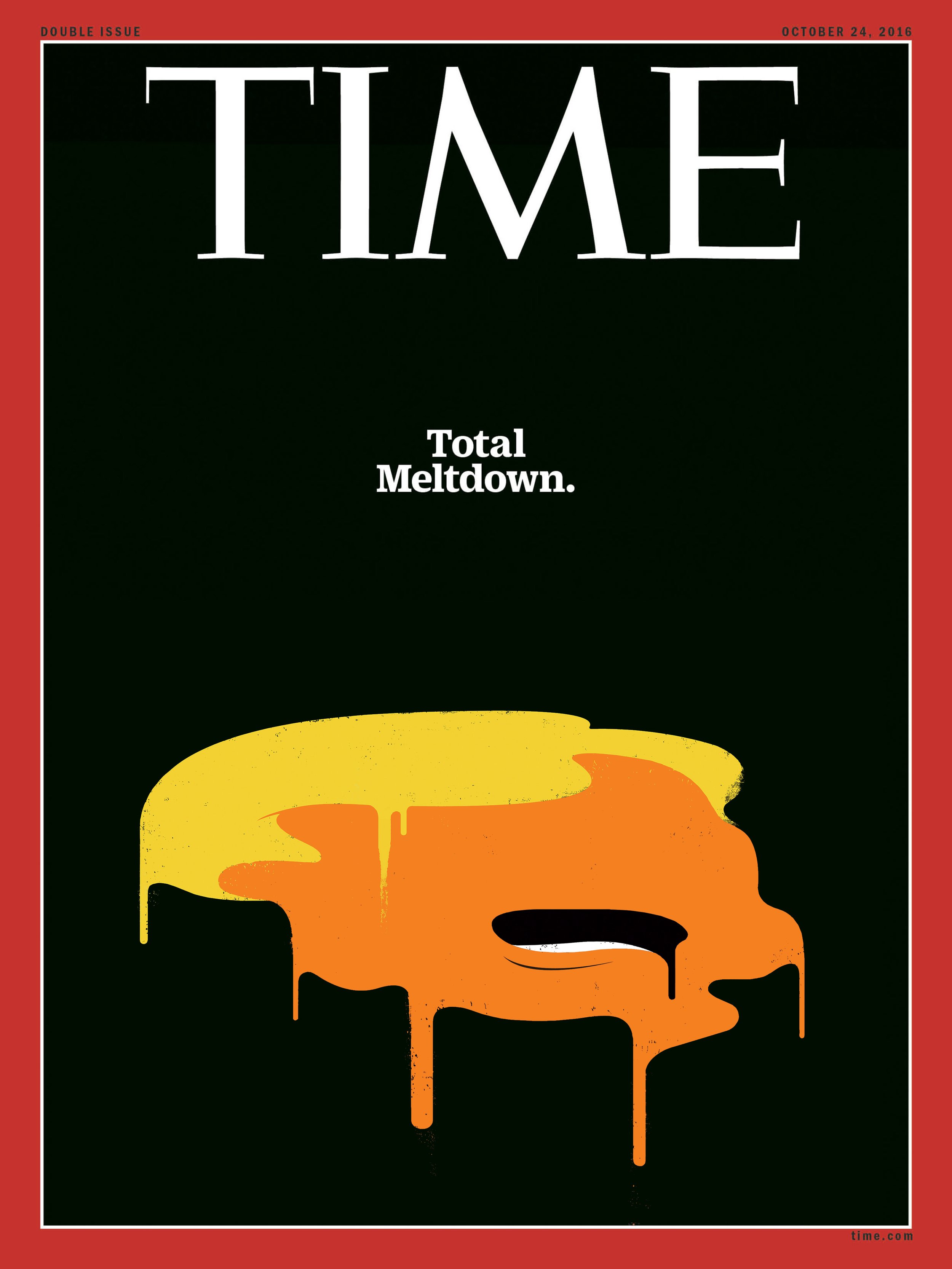

George Gendron: I have to confess I’m not shocked to hear you say that. So just about everybody in the world—and I’m not just talking about media people—has seen one or many of your now legendary Trump magazine covers and illustrations. And yet very few people really understand where this came from. A lot of people think that it started with the Time “Meltdown” cover. But in fact, you were at this before that. Would you share with us, from your personal point of view, where did this Trump phenomenon that you’ve created—this visual phenomenon—where did it start? Go right back to the very beginning.

Edel Rodriguez: At the beginning, if you go a little further back even, I had already done one kind of a series of protest work against ISIS, the Iraqi group that was doing all sorts of things to women, destroying art, things like that. And I didn’t feel that the United States was paying enough attention to this sort of islamic fascism that was happening.

So I began creating an online campaign and offline posters about ISIS in 2014. And then 2015 rolled around and I saw this extremism happening here in the United States with these MAGA crowds and violent political rallies, which was pretty shocking to me.

So I started making images. I took some of the images that I had done about ISIS and just flipped the script and would change the colors or put a little red hat on the extremist. And it became this right-winger in the American context. And then when Trump started, when he showed up at the primaries, I noticed that the media treated it all as a bit of a joke, as a funny story.

And after I began seeing some of his speeches and the way he was treating, he was, the way he was hyping up the crowd and using words that were very similar to the words that I grew up with, like scum, vermin now is a new word that he has. But in 2015, he was already doing that. So I began this online campaign creating images of Trump being an extremist.

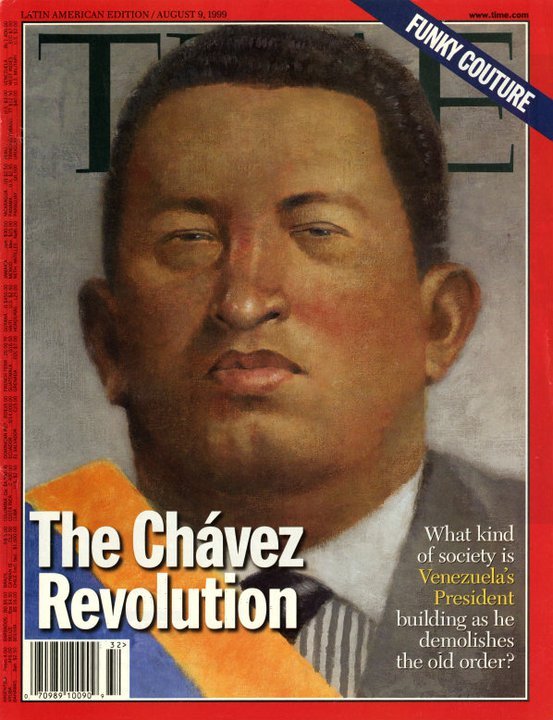

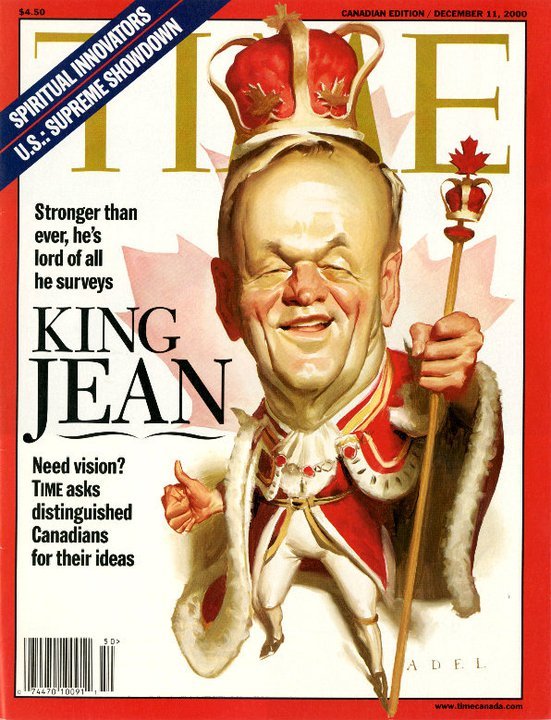

So I was doing that in 2015 and 2016 during the primaries. And my thinking was I had worked at magazines for a long time. I worked at Spy magazine for a bit back in the nineties and then Time from 1994–2008. And I’d also done some work for The New Yorker and I know what the conversations that I had in the meetings—What can we do? How far can we take this? How do we cover this candidate?

“The other thing people would say is, ‘I’m not crazy. This is really happening. Your image makes me think that I am not crazy.’”

And in the primaries, there is an overall sense that the media has to be super, super neutral. That we’re just presenting information. And I felt that this was different. Like we had arrived at a different point in American history where the media couldn’t just do a “both-side-ism” thing. I felt the media needed to actually say, “No, this is wrong. You can’t do this.”

And I felt if I stuck my neck out there and started making these images, maybe it would influence some of the art directors and magazines that I work with to actually hire me and create this kind of very strong, confrontational magazine cover rather than just what is typically done, which is a nice photo shoot of the candidate.

And that was my goal. And I think after having done it online and also realizing that magazines want attention nowadays, this work was getting attention. It was getting attention from an online crowd—comments, likes, things like that. And it was picked up, it was noticed that it was getting attention, and it was pretty accurate.

And at one point I got a call from Politico in the United States to create something around that. And also from the Washington Spectator. I was doing small spots for them. And then in August, when Trump had become such an extremist that he was mocking the family of a slain American soldier, and that’s when I got the call from Time magazine, which took what I was doing, which was a small-level kind of thing, and burst into the scene and into the political arena.

George Gendron: I don’t know about other people, but one thing I know that had a certain kind of impact on me was that a lot of illustration, even the most really outstanding illustration these days can be, I guess I would either call it neutral or abstract. And there was something emotional and vibrant and visceral about your work that I think people felt, “It’s okay to feel that way.” It gives you a sense of permission. “This is bullshit!” Fill in the blank. It was really cathartic.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, and that was the emotion that I was getting from people when I was working on the project on my own. Then when it showed up on magazine covers—yeah, those are the good messages that I would get from people. “Thank you for saying what’s on my mind. Thank you for making a picture of what I think is happening.”

And the other thing people would say is, “I’m not crazy. This is really happening. Your image makes me think that I am not crazy.” Because what Trump would do is—it’s like the classic person that would do something and then say, “No, I didn’t do that. I didn’t do that. I didn’t say that.”

And then there’s an image that comes out two days later that says, “No, in fact, you did say that. Here’s an image.” And at the time I started thinking I want this to be the history. I want this to be recorded. These things actually happened and that there was at least one guy, one illustrator out here going, “Fuck that. We’re not having it.” To me, it was a very personal thing.

At some point he came up with the idea—him and that other weasel-y guy, Stephen Miller. He’s a really evil guy. He came up with the idea of finding ways to deport people that were already US citizens that may have committed a crime at some point, or may have done “something.” And I’m like, “Wait a second! Now they’re coming after me.” I don’t know exactly what card I had when I came into this country. I came during the boat lift. But you get a little paranoid. I’m like, “Have I done something wrong in my past? Am I going to get deported back to Cuba 30 years later?”

So it was a very personal thing, not just for me, but family members that could be deported for whatever random issue. Just that the conversation is even being had. That we’ve gotten to the point where we can’t just accept that Americans are here. We’re going to start looking into your histories and many other things.

I grew up in Cuba as a kid where if someone punched you, you got into a fight. You punched him back. I wasn’t raised to be gentle. And my father was always like, “No, hit him harder!” So that’s the way I tend to function. When someone’s doing something, I’m going to be doing something right back that’s just as strong. Or even stronger. And it’s just moved into graphic art.

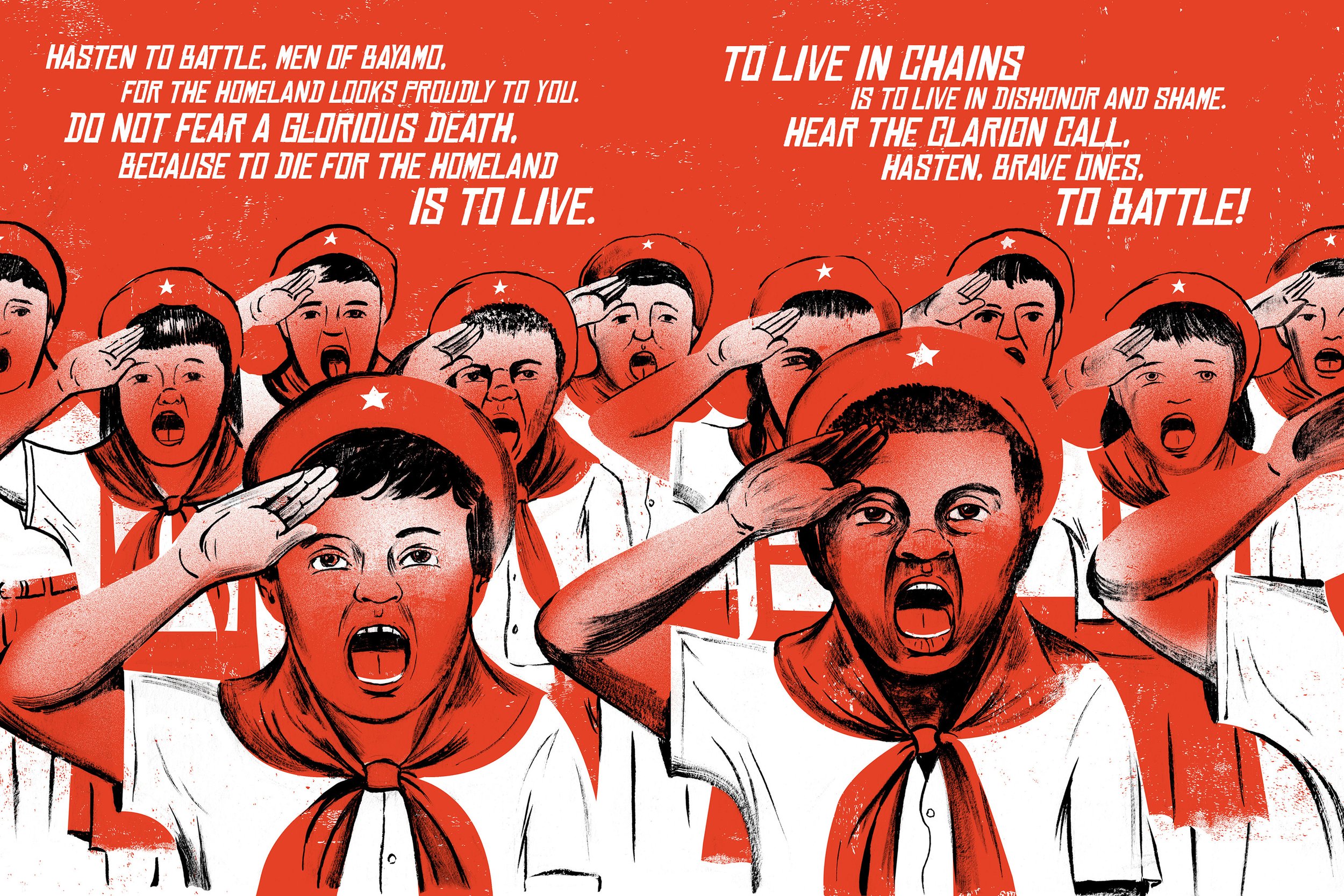

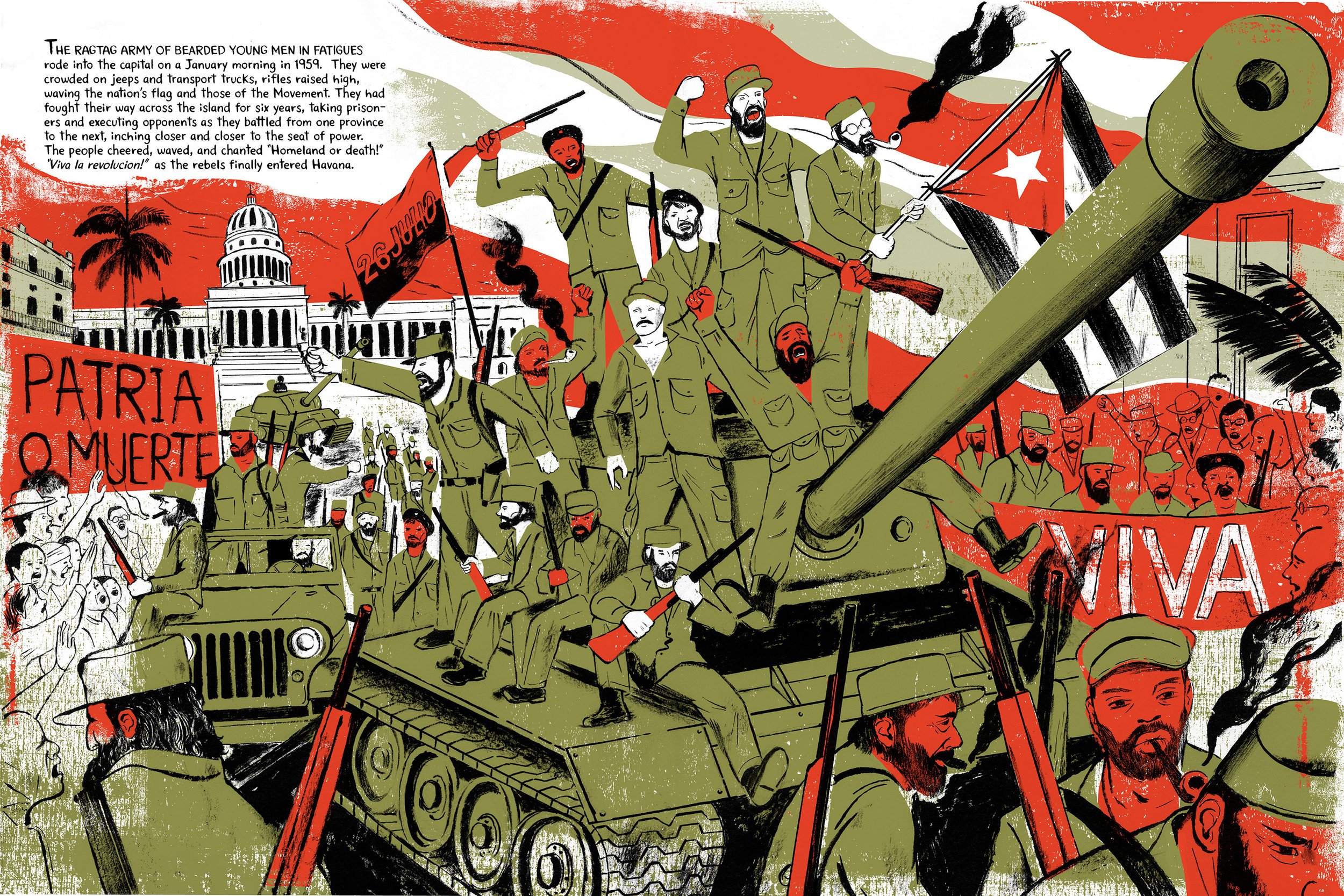

George Gendron: And as long as you’re talking at this point about growing up in Cuba, you have to have been influenced by the impact of revolutionary art.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah. I don’t think you can avoid it, especially growing up there, your entire school is filled with these posters, the notebooks that you look at. There are slogans all over the streets, saying, “Homeland or death!” All sorts of things.

Over the years, you look at it from a different point of view. As you get older, you see it as, basically, really smart marketing and propaganda. You see what works with that kind of stuff. And maybe I can use these tools for good. But yeah, some things in my work are influenced by those kinds of graphics.

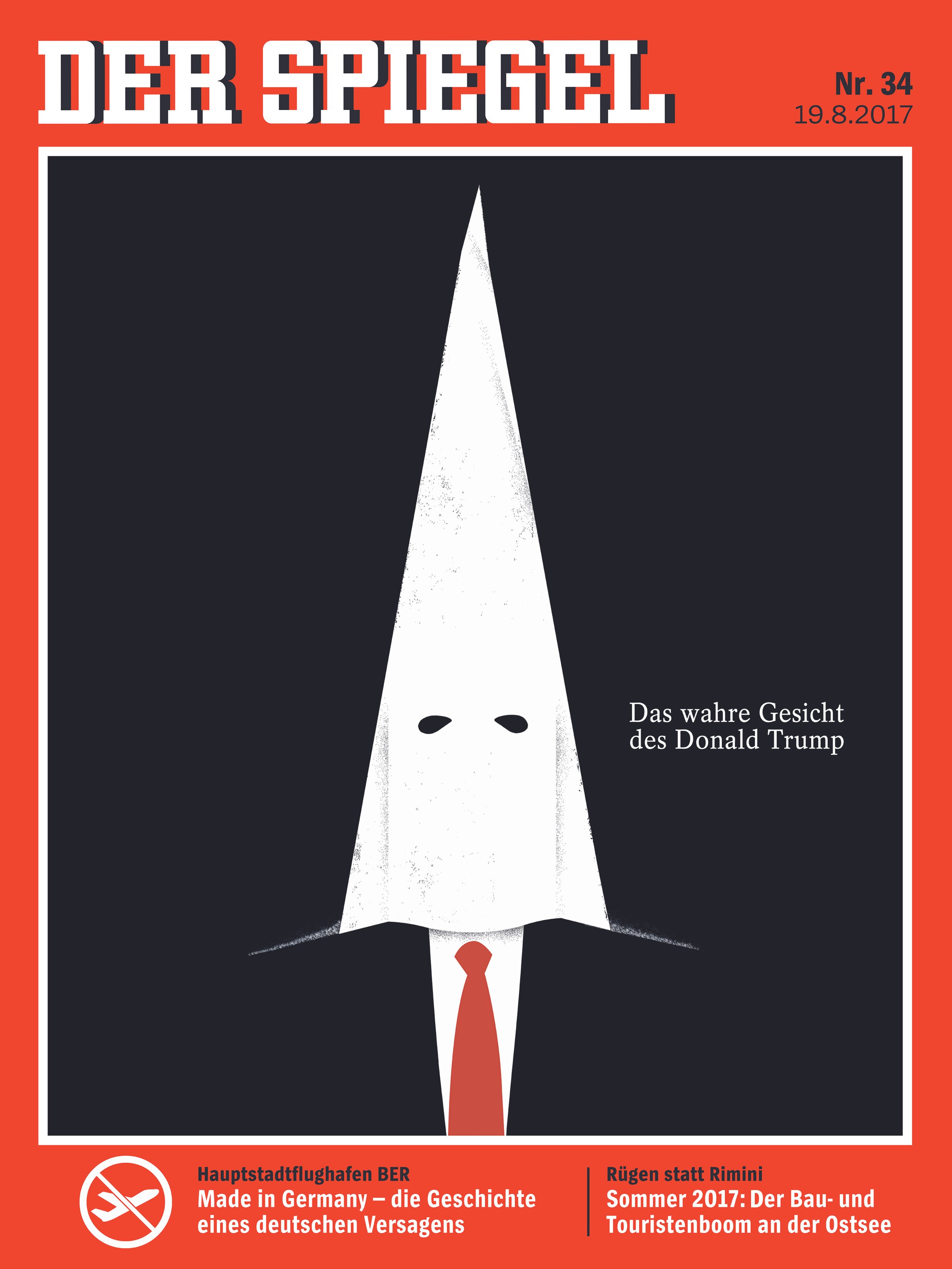

George Gendron: Yeah, I want to come back to that later because I think that’s very powerful when we talk about your book. I want to transition now to that first Time cover—which I think was, “Meltdown”? I want to go to your most incendiary cover, probably, for Der Spiegel, where Trump is holding the head of the statue of liberty in one hand—the severed head—and a knife, dripping blood in the other. And even your mother thought you had gone a little bit too far.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah. That’s when she thought, “Okay, I’ve got to say something.”

George Gendron: Tell us about the reaction to that cover.

Edel Rodriguez: The cover came, again, from the ISIS imagery that I was doing, and I was just very angry at the idea that immigrants were being held at the airport and that he just, on his own, signed an executive order to ban anyone from Muslim country to come. And there were little kids, old ladies, grandmothers just stuck at the airport.

And I took one of those ISIS images, which was basically an image of a terrorist beheading himself—they were beheading people left and right. And I’m like. “This has gone so extreme that they’re going to create the end of this ISIS movement. They’re going to behead themselves.” So I took that image and I just slapped Trump’s head on it and put the Statue of Liberty on one hand, and I put it up on my Twitter feed.

A lot of things were happening back then. Now I don’t really post that much on the new X platform, but there was a lot of stuff happening on Twitter and Instagram, and it went pretty viral. It’s actually one of the most-shared images that I’ve ever had on its own.

Then about two days later, the art director of Der Spiegel had asked me to create some sketches on the topic. And as I was working on sketches, she was perusing my Twitter feed and saw that image. And she said, “We really like this. We want to publish it.” My first reaction was, “No! You guys are crazy, you can’t publish this. It’s just me screwing around online. You can’t possibly do this!”

And she says, “No, it’s perfect. It’s perfect for what we want to say.” And the editor of Der Spiegel loved it too. And it was a person wearing a tunic, so they wanted to have Trump’s suit on it. So I did that revision and I sent it over to them.

And past covers that I had done, I thought they were over the top, but not that much. And in this case, I actually told a few friends of mine, “Something’s coming out tomorrow that I think is gonna be pretty crazy and problematic.” It was posted by Der Spiegel at 6pm on a Friday night on their Twitter feed and on their website. And within two minutes, I was getting calls from The Washington Post, ABC, NBC, asking me, like really animate, “Did you do this? Why? What is this? What’s going on? Who are you?”

And I explained why I was so upset about what was going on—that when you’re an immigrant, these things tend to feel a little bit closer to you. And they quickly wrote a few stories. I think within half an hour, The Washington Post story was already up. And the angle became me, an immigrant child, is basically confronting the president of the United States. At that time, he was already president. So it was even. But I don’t really care. I just, I’m here doing my work, and that’s what comes out.

George Gendron: What did your mom say to you?

Edel Rodriguez: She called me, and she said, “When did you become a cheap artist?” That was her quote. She had seen it on Facebook. And that made me mad, so I hung up on her and then I unfriended her from Facebook. I was like, “If you’re gonna be calling me out of the blue with commentary, then you don’t need to look at this stuff.” So I took her off Facebook and we didn’t talk for a while, and she was really upset about it. Eventually we fixed it all up.

George Gendron: What was a Thanksgiving dinner like that year?

Edel Rodriguez: I don’t go there for Thanksgiving, so that’s good. And eventually my dad called me and it’s, “You really got to talk to your mom. She’s really upset.”

I’m like, “She can’t be doing that.”

I think it was a few things. Politically, she was still like a little, not completely against Trump. She thought he was okay. There’s something in Cuban culture or sometimes Latin culture where if someone’s the president of the country, you should respect them. It’s the person that’s representing the country. And also the fact that it was dangerous. That what I was doing could affect me. And some of the reactions online, where people were threatening me, upset her. And she was trying to get me to not do this stuff.

George Gendron: That leads to my next question, Edel, which is how serious did the threats get for you or your family?

Edel Rodriguez: There was a lot of online chatter and subtle threats. It wasn’t direct. It was. “You should have drowned on that boat you came on. In another time, people like you would have been summarily hanged.” That kind of, “I’m not going to do this to you, but this should happen to you.” And a lot of it was online comments.

But then at some point [Steve] Bannon’s website put my email up, “If you want to send this guy any messages, here’s his email.” And I immediately started getting a lot of direct emails that were more of the same—“You should die. You don’t belong in this country. Get out of here.” But there wasn’t anything that I felt I needed to call the police about. But I was much more wary there for about two or three months, than I should be as an artist in this country.

George Gendron: Has that died down now, or does that get revived anytime you do something controversial?

Edel Rodriguez: It goes up and down. It depends. If it’s something that is confrontational, then I’ll get more of that. But I don’t really pay that much attention to it. It comes with the territory. If anything’s close to a threat, I save it. I have a folder called ‘Hate Mail’ on my desktop where I save who sent it and things like that just to keep track of what’s going on. And for a while I didn’t really talk about where I lived or any personal details and things like that. But it’s been okay.

George Gendron: A taunt like, “You should have drowned on the boat you came here on”—we used to say that all the time in New Jersey. But we were second graders.

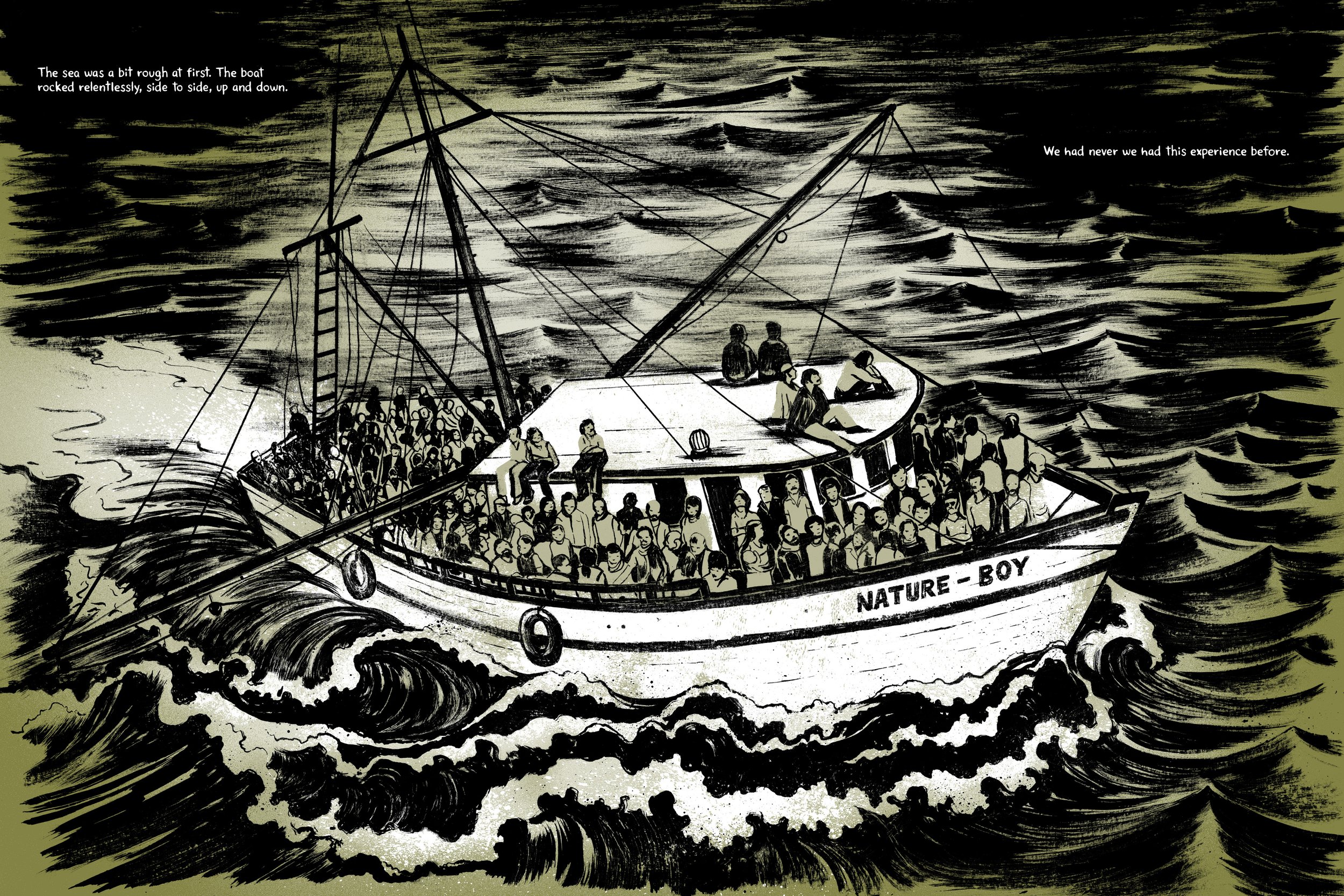

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, I mostly feel bad for these people. Like, why are you doing it? Why are you sitting there writing an email to someone who just made a drawing? People ask me, like, “Why do you take risks?” And I really do not see it as taking a risk. I see getting on a boat with your children and coming to America—that’s a risk. Me drawing a picture is not risky. I draw pictures all the time of all sorts of weird stuff.

I’ve been drawing pictures since I was a kid and I’m not aiming a gun at anybody. I’m not starting a fight. I’m taking some ink and putting it on a piece of paper. And if I don’t do that, then I really can’t call myself an artist. If an artist sits there, has an idea, and doesn’t make it because they’re afraid, then you’re not an artist. You should really be putting out what you feel.

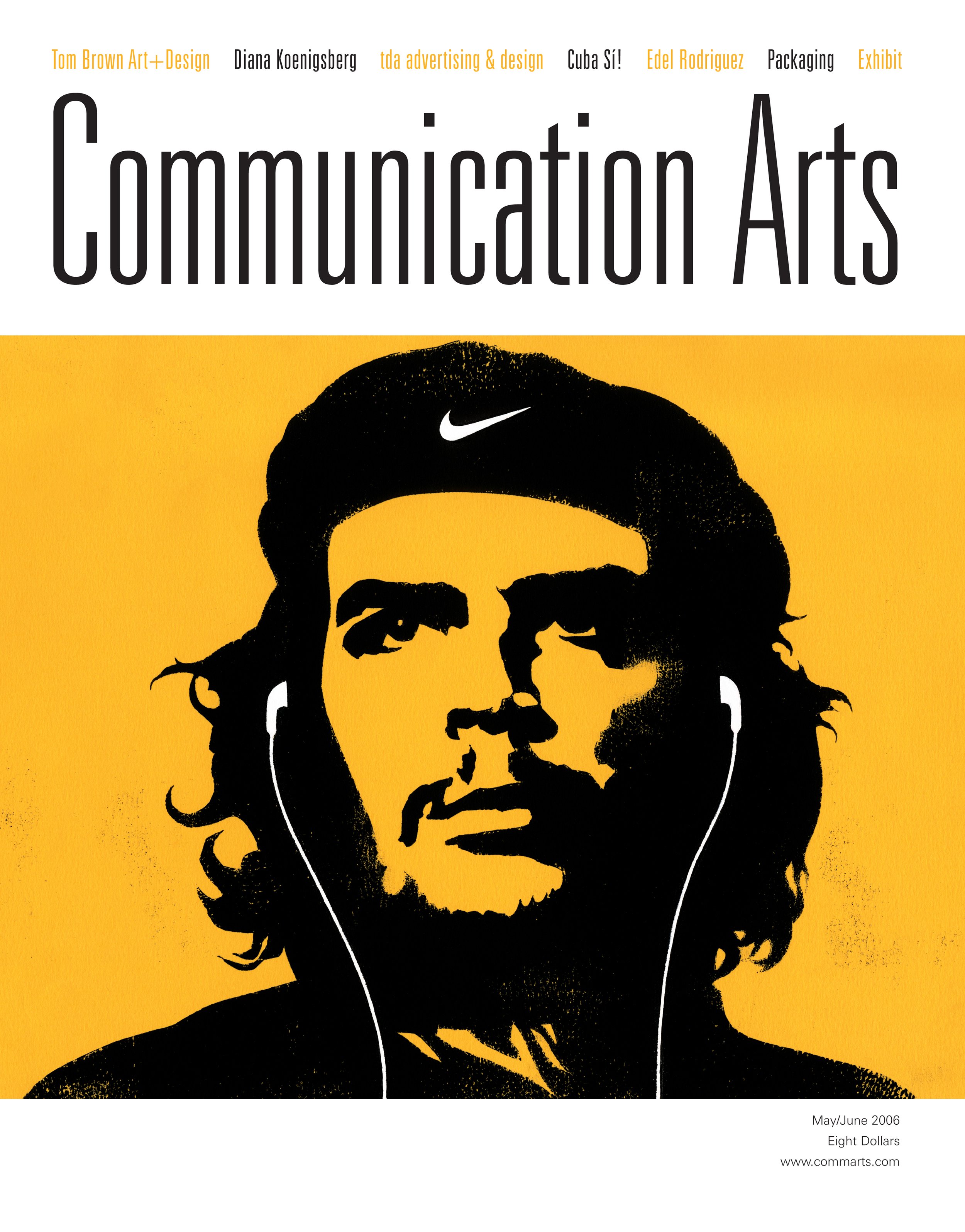

George Gendron: I know what you’re saying, but let me push back a little bit, because I think, the image that you have come up with for Trump—no eyes, no nose, just big, bold swaths of color, a mouth—that is subversive because it’s a reminder that this man, all he can do is spew hate and anger. That’s all he does. Anyone who is a Trump supporter, I would view that as subversive.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah. But its purpose is not just to provoke. Its purpose is actually to get that person to go, “Why did this person make this? Is there something here that is true? What do I feel about this image? Why did someone go out of their way to bring this into my life?” I’m really not that interested in changing the minds of people that are already there, and all the way out on the fringe. But there are a lot of people in the middle. There’s a lot of people in the middle, and I’m interested in making them question, “Why are you voting for this person? And why do you feel this way?”

This is basically me having a conversation with my family—with cousins, and uncles, and stuff that feel these ways, that think that way for a variety of reasons, some of which I don’t think are good are reasons that good people should be feeling that way. Some of them are racist. Some of them are misogynistic.

He is playing to that in these people. I come in and I make images that comment on these aspects of this candidate, so that you go, “Why do I agree with this person? Why am I voting? Am I a misogynist? Am I a racist?” And I think it’s important because I do think there’s a lot of people that can go one way or the other. And they have very selfish reasons, very racist reasons for doing what they do.

George Gendron: You seem to be constantly flirting with an edge, and I think at one point your expression was, “I’m constantly pushing the limits of censorship.” Have you ever gotten any official feedback or pushback to what you’re doing?

Edel Rodriguez: No I never did. The only time I heard from the White House was actually someone that worked there that wanted to buy a print. And I thought it was a trap. He said, “I want to buy a print from you.” He didn’t say exactly which one. And I said, “I’m not answering this email. I think it’s a trap.”

Then a week later, he sends me an email again. And he eventually explained that he was a naval officer during the Mariel boatlift, and that later, as a Coast Guard officer, helped a lot of Cuban refugees get off their boats. And he wanted to buy a picture of mine that was a drawing of my family on the boatlift.

And I was like, “Wow, this guy’s genuine. He just wants to collect something that I made.” So I said, “I’ll send it to you. You don’t have to pay anything.” And I sent it to him. And it wasn’t really about politics. He just liked some drawings that I had published in The Washington Post about the Cuban boatlift.

George Gendron: Well, if you’ve never gotten any official pushback—or didn’t get it when Trump was in office—maybe you need to push a little harder, man. I’m curious about how you work with your clients, particularly in the arena of media, on any illustrations, not just Trump. Do you do roughs? I’m sure it varies from one client to the next, from one organization to the next.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, most of the time I get a message saying, “Are you available? We have the story for you.” And I get the story, if there is a story. Sometimes there isn’t a story and it’s just a synopsis and by this point they just trust me to do whatever I think makes sense.

And I do some drafts. I do four or five, six, maybe 10 sketches, for a cover or an interior, and send it to them. And I tend to work with pretty good art directors, so they usually have a pretty good sense of what’s the best from the set, and they pick one sketch or we have a conversation about it or I say, “I think this is the best one.” And a little back and forth. And then I go ahead and do the final art.

But yeah, it’s mostly through roughs. That’s generally the way it works. Occasionally I have an idea and I create it. Or I sketch it and I send it to someone that I have already worked with. I do that sometimes with The New York Times Op-Ed page, or Der Spiegel, or even Time magazine.

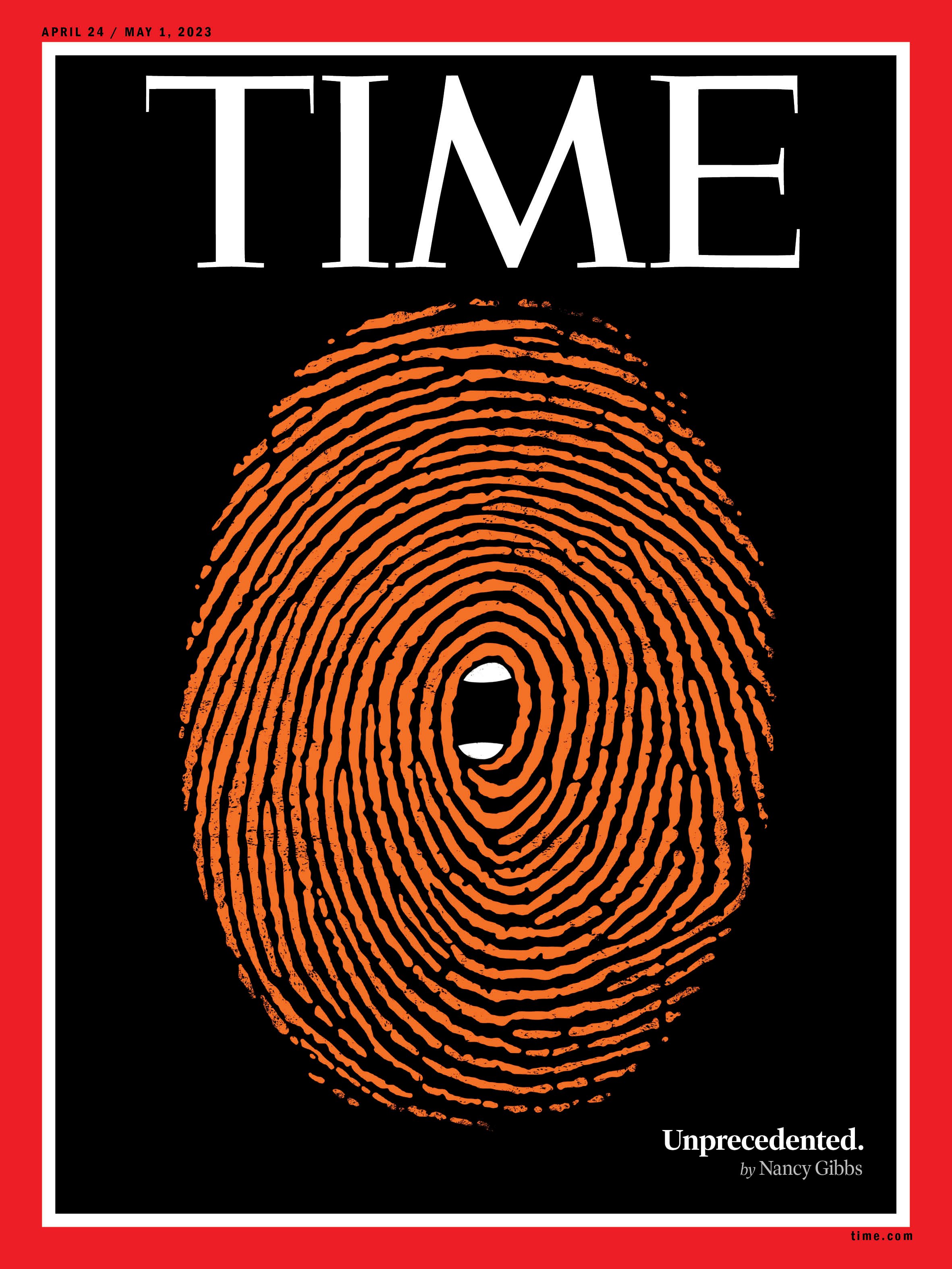

I’ve sent ideas to the art director there, and I say, “Look, this is happening in the news. I have this idea. Are you guys doing anything on this topic? And if it clicks, if they are covering the topic and my image works, then we do that. Other times, like the last cover I did on the indictment, the art director D.W. Pine put me on the beat and he says, “Look, we don’t know what we want yet, but we know there’s going to be an indictment next Tuesday or Wednesday. Can you watch the story and see if you come up with any ideas as it develops?”

So I sent them things as the story was developing. I would send my ideas and then finally, on the last day when they finally indicted him, I thought, “Nothing really happened here. All they did was take his fingerprints.” And that’s when it clicked in my head, “Just a fingerprint. That’s the idea!”

I tend to have conversations in my mind. I knew that he was waiting to get pictures from the situation and I had been in that position of being an art director at Time waiting for pictures. And I realized that there were no good pictures that were going to come out of it, because everything was in the back room. There weren't really high quality photographs of the event. So I was like, “Let me send one more idea because I don’t think they got anything today.”

And that’s when I sent that idea. And he’s like, “This is amazing! Oh my God, I want to show it around.” And he showed it and they went with it. Some of it is timing and understanding how publishing works. That has helped me a lot. I think having worked at Time for that many years helps me to understand the schedules and how things develop there.

George Gendron: I want to get to Time in one second. It’s a great story. I think of it as your first big job. But before we do, you grew up in a communist country. Does that have an effect on your ability to negotiate with your clients?

Edel Rodriguez: What I did like about publishing when I first started out in magazines and newspapers is that everything was set. Every magazine had their budget. It was, for the most part, fair. You were just told this is our budget. So there wasn’t really that much negotiating with magazines. But now I do think that’s come back a bit. There’s a lot of competition, but also that magazines are trying to spend less money. There’s a bit more back and forth now.

George Gendron: After your Trump work became as publicized as it’s been, did you raise your rates?

Edel Rodriguez: It depends on the situation. Not with people that I regularly work with, but with other people that are coming in out of the blue, yeah, you feel a little bit more confident. And you’re like, “No, I’m not going to do it for that much. I’m busy already.” Occasionally I do raise my rates.

George Gendron: I know a lot of our listeners are going to be really happy to hear that.

Edel Rodriguez: Everybody’s raising their rates. I think my haircut was like $15, now it’s almost $25. So everybody is raising their rates. But I think it is very hard in the art business to do that because there is such a glut of artists and so many people doing things.

I think for us living here in the United States the business has become much more international. And while that’s good sometimes for us, you have illustrators in other countries where getting paid $300 is a fortune. So you’re competing with that. And I think that has affected the business as well.

“I warned you! I was doing work in 2016 that was warning that this could happen—an insurrection and a takeover of the government. And it happened!”

George Gendron: Let’s talk for a minute about your first big job out of Pratt, which was working at Time. Could you recount that story? That’s a great story.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, I had worked at the school newspaper, and it’s the only graphic design experience I had. We were putting out a newspaper about once a month. And it was great because we were doing our own illustrations, our own design, all of that.

And I put together a little portfolio. And right before I graduated, my English teacher announced to the class, “If anyone’s looking for work someday, call my husband at Time magazine. He’s looking for a young designer.” And I listened to it, but I didn’t go for it right away because I thought that I needed much more experience to even be considered there.

So I spent a long time calling magazines. I would just go to the newsstand and look at the mastheads. And I called Details, Vibe, newspapers. I went and interviewed at The Village Voice. But I think after 60 tries, nothing worked out. And that’s when I remembered what this English teacher had said, and I’m like, “Oh, let me try it.”

So I looked up her last name, which was Conley. And I looked up on the Time masthead and there was a guy named Steve Conley. And just out of the blue, I called the general number there. They put me through to him and I said, “Your wife said that if any student was looking for work, that we should call you.” And I said, “I’m looking for work.”

And he said, “Come on over tomorrow. I’ll take a look at your portfolio.”

So I went there. I got all dressed up in a suit and everything. I showed up at Time and the first thing he says is, “You got dressed up for this thing, didn’t you?” He was there in a t-shirt and jeans. So I walked in and he brought me to his office and he looked at my portfolio from The Prattler, the school newspaper. And he says, “Oh, this is really good work. Let me see … there’s someone that’s leaving for two weeks on jury duty. He delivers the mockup around the office and sets up the mockup wall. It’s pretty easy work. You want to do that for a couple of weeks?”

And of course I’m thinking, “Yeah. But what happens after the two weeks?” So he started me there for two weeks delivering things around, and while that was going on I, as much as possible, would just say, “If you guys need help, I’ll design a page for you.” And they threw a couple of pages at me. And they kept me, and they kept on keeping me there, for I think it went up to nine months.

And by that point, after seven months, eight months, I was getting interview requests. The New York Observer was looking for an art director. And I went there to interview. And I would come back and I’d tell this guy, “Listen, if you don’t give me something here I’ll just have to go somewhere else.” And he talked to the higher-ups and they offered to hire me as an entry-level designer there at Time magazine. That was in 1994.

George Gendron: And you describe how, as an art director, working with illustrators had such a huge impact on you, because you could then watch how they worked, how they promoted themselves.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, I think it was better than school. I had taken some illustration classes at school, but it was really more about technique, and ideas, and the art of it, but not really the business of it. So once I got there. I was working with Steve Conley and I was also watching what Arthur Hochstein was doing, who was the main art director. And I would hang out in Arthur’s office, like Friday nights to just see him designing covers and hiring great artists.

We would have sometimes three or four different pieces of art come in on a Friday night. I remember once, the “Man of the Year” was the Pope. And there were these beautiful paintings of the Pope, and [Arthur was] making decisions and which one they would run with. And Arthur was a mentor as well, and it was great working with him and just hanging out, watching him develop covers.

But it was that process and seeing how someone like Barry Blitt would send in, like, 10 sketches. And I would look at all of Barry’s sketches and how finished they were. Brad Holland was doing a lot of work for the magazine as well. So I learned a lot from that process—how they made the work, how they delivered it, and also the promos that came in. And that’s when I figured out, “Oh, okay. So this is what an illustrator is.” I didn’t really understand it before I went to Time.

George Gendron: Yeah. And back then, even if you had immersed yourself in, let’s say, illustration in art school, they wouldn’t teach you that. How do you promote yourself? How do you position yourself?

Edel Rodriguez: No, I think there was probably, like, one business class. And a lot of times, what happens in schools is that they’re teaching how things were done 10 years earlier, let’s say. They’re not really teaching exactly what’s happening in the business at the moment because the business is always changing.

George Gendron: You mentioned Brad Holland and Barry Blitt—who else comes to mind when you think about some of the illustrators who had an impact on you?

Edel Rodriguez: Marshall Arisman, Sue Coe, Francis Jetter, Alan Cober. Chris Payne was also very popular on the cover—he came in the office once in a while. Anita Kunz. Time had the wherewithal and the budget to just hire like the very top best. And everybody would stop their schedule to do a Time cover in two days. Tim O’Brien. Tim O’Brien was actually pretty young back then. But he was already doing covers for the magazine. And Tim’s become a good friend of mine as well. And also what happened is once you got into Time magazine, it just flowed down from there. You could do covers for almost any magazine.

George Gendron: Let’s transition to a book called Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey, which is this absolutely extraordinary graphic memoir of your life growing up in Cuba all the way through to today. And I don’t even know how to begin to tackle this subject because we could spend days just diving into every single aspect of that book. But first of all, how did you go about the process of making that book? And by that I’m really curious about whether you storyboarded it. For you as an illustrator, did images drive this and the text followed? Did the text drive it? Was it a really iterative process?

Edel Rodriguez: I would say now it was maybe a 12 or 13 year process from the very beginning. You know, earlier than that I was doing picture books, and whenever I met one of my editors for children’s picture books, they would ask where you’re from and I’d start talking about Cuba. And then telling the story and they would start salivating. They’re like, “Oh my God, this is an amazing story. You should put this into a book.”

And I was like, “I don’t know. It’s a lot of personal stuff.” But then you hear that over and over from editors. “This is a great story. You should write a book. You should write a book.” And then I went up to my children’s book agent and I said, “I keep hearing this. Should I write a book?”

And she’s, “Of course! You’ve got to do it. You’ve got to write it.”

And so she got me to start thinking about it. And I’ve never written a book or made a graphic novel. So my first process was to just start making visual notes of the events of my life. And I would make little visual sketches, quick sketches, quick, random moments that I remember, and I would put it in a scrapbook. And I kept putting things in the scrapbook—photographs, how I would treat a page or a chapter opener, how I would treat the panels, all that. So all that, and I thought that would, somehow, magically become the book.

But then I realized that doesn’t happen. So I realized I had to actually write an entire book. I thought it was just pictures and then some, like, random little notes. No, that’s not it. So I had to put that whole thing down. And then around 2014–2015, I did interviews with my father, my mother and my sister and got a lot of information about them.

And then later I needed more of the point of view that I didn’t know, which was my family here in the United States. And I got really interested in the whole planning of it. And how, basically, I’m here through a whole series of random events that happened, a lot of it could not have happened. Anything along the way could have made this whole thing fall apart.

As a Time magazine art director, Rodriguez was able to commission covers from many of his illustration heroes.

George Gendron: That’s what’s astonishing about that story. It reads like a detective story. Seriously! You’re on the edge of your seat thinking, “Are they gonna get out? Oh my god!” And then something else happens.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah! And it was like that. So I was trying to take my memoir part of it—what I remembered—and tie it up with facts. Tie it up with the days of the week, the events that happened in April and May, and the larger story of the Cuban revolution, trying to push out as many of the worms, or the bad people, as they could. Because we were becoming a problem to Castro. Castro saw the boatlift not as a humanitarian thing, he saw it as a way to clear out the country of the scum, and the worms, and all these people that were making his life on the island miserable. Because there were a lot of little protests that were happening.

George Gendron: But that also included convicts, right? There were some pretty hardcore people that he was also trying to get rid of.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah, that was the plan. He agreed to get these families out that don’t want to live there, but in the back of his mind, he’s, “This is how I’m going to clean out my prisons, how I’m going to clean out my insane asylums.” He had gays in prison, all sorts of things. So that was his plan: get rid of the opposition and anyone that was deemed antisocial. That’s what he would call them.

So getting that, getting my family’s point of view, then the other family members who went to pick us up, and then my memories, and tying all of those things together. That’s when I was finally, “Okay, I got all the background information. Now I have to sit down and write the chapters.” And it was dividing the thing into about 19 chapters that helped me take all of these different stories that might seem random, but would help me bring them together into a narrative that develops over time and goes up and down.

And as you’re following this family, you think, “Oh my God, that’s it. They’re not gonna be able to get out of here.” Then they do. But then, when they arrive, it gets complicated again. So it was that whole story that I really got into. And then I spent a year writing a book, basically. It was about a 250-300-page manuscript.

George Gendron: Was the writing difficult for you?

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah. Writing was the hardest part because it’s a lot of tying knots together. You have to make sure that things add up, things come together, describe things. I described a lot of things in the text, and then when I started bringing my images, I realized I don’t need to describe this much stuff, because I’m going to be showing it. So after I wrote it, then it was a matter of editing it down, so that I’d have enough room in the book to, to include the images and the pictures.

And then also working with my editor, Riva Hocherman, I sent her a very large manuscript and she was like, “We don’t really need four chapters on this whole Trump situation. We all know what happened.” So she brought a lot of that down and changed it.

She wanted me to write more about my personal take on it and what I was going through rather than the whole country. So it did help to have her as the backup person and also to get me in gear with the deadlines, because I signed the contract in 2019 and they wanted it by 2021-2022. And they finally got it at the end of 2022. But yeah, once the whole manuscript was set, then it was just a matter of drawing. Making about five, six drawings a day.

George Gendron: If you delivered the manuscript in 2022, as you said, every writer I know would say, “That was early!”

Edel Rodriguez: No I know. I think that they felt that the story was very timely and they wanted it out as soon as possible.

George Gendron: Yeah, I can see why. And I think the way you close the book, brings it home in a way that’s very dramatic, especially those two illustrations that are bookends. People should buy the book and then look at those two illustrations. Did you have graphic novels or graphic memoirs that inspired you or were you just on your own here?

Edel Rodriguez: I’m not an avid graphic novel reader, but I have always liked Persepolis and Maus. Persepolis is a book about the Iranian revolution by Marjane Satrapi. And then there’s Maus by Art Spiegelman, and then the works of Joe Sacco, who’s also published by Metropolitan Books, who published my book.

Whenever I saw a graphic novel that dealt with real events that were political and about a real person, I always got more interested in those. So those would have been like the ones that I read and thought, “If this book can be published, maybe my story can be published too.”

And I also liked the books, Night by Elie Wiesel, 1984, Animal Farm. Anything that dealt with political things. When I was a kid I was attracted to it because I was trying to figure out, “Why did these things happen? Why did this happen to my family? Why did we have to leave?” So I was looking for answers and always found that in political books, or books about World War II, or the Holocaust.

George Gendron: I remember the effect that reading Night had on me the first time I read it. By the way, the original draft of Night was 800 pages.

Edel Rodriguez: Wow. Really?

George Gendron: It was cut down to, like, 240 or something.

Edel Rodriguez: Yeah. It's a very short book.

George Gendron: And I think part of the power of it—and I think this is also true of the way in which you’ve utilized the graphic novel format—the power of that is the clarity of it and the simplicity of it, in a way.

Edel Rodriguez: And I’ve noticed it’s made an impact on people that generally would not pick up a book. They pick up this one like, “Oh, okay. This is different. I can see it. It feels much stronger.” There are books that have been written about that boatlift by Reinaldo Arenas, and Finding Mañana, a book by someone that I know named Mirta Ojito. But seeing what occurred in graphic form just gives it a little bit more, I don’t know, vibrancy or intensity.

“We were becoming a problem to Castro. He saw the boatlift as a way to clear out the country of the scum, the ‘worms.’ All these people that were making his life miserable.”

George Gendron: It brings it to life. One of the things that I personally found most striking is, it’s a right-hand page where you recount, in captions with some really interesting, very dark illustrations, bedtime stories that were told to you. So if you don’t mind, I’m going to actually read you this one. It’s very short. So you start by saying, this is you:

“Nights were spent on the porch. Mama—your grandmother—would sit me on her lap and rock me to sleep. She’d tell me stories of war and freedom. Of animal sacrifices and backyard potions. Deadly storms. Famines. Santeria priestesses and sacred tree roots. One tale involved a young blonde girl in a white dress. She disappeared one day and search parties went out to the countryside. Bands of people efficiently searched through the dense sugarcane and found her days later. She had been beheaded in a ritual and was lying among the sugarcane. This was typical of Mama’s story, with their slow, methodical, enticing storyline. And then a disturbing ending.

So I have to ask you, 40 years later, do you still sleep with the light on?

Edel Rodriguez: Can you imagine you’re five-years-old and this is what your grandmother’s doing to you? But I thank her every day because she gave me so many images. If you see some of my work and you think it’s disturbing, blame my grandma.

George Gendron: What kind of bedtime stories have you told your kids—or do you just read them the news every night?

Edel Rodriguez: No. They just picked up Eric Carle books and, like, typical American children’s books. And they read a lot of their own now, actually. But yeah, it was a different place. In our town, especially, it just felt like some other world. At night there were no lights. Everything was super dark, just the stars out in the sky. And even when I go there as an adult, “Wow, this is a different place.” This is detached from the rest of the world in a way.

George Gendron: what have you, are you able to, now that Worm has been published, can you go back to Cuba?

Edel Rodriguez: I don’t think so. I’m not testing it for now.

George Gendron: Have you heard from friends or fellow artists in Cuba who have managed to somehow get their hands on the book?

Edel Rodriguez: No, I haven’t heard from anybody yet. I don’t know. It’s a very complicated situation. I don’t really know how to handle it yet. I had someone that’s in Miami, they’re really excited that this book came out, and they wanted to donate a copy to the National Library in Cuba.

And I’m like, “No, I don’t know about this.” Or like my book publicists made a list of organizations to send the book to, and at the top of the list were dissident groups in Havana. I’m like, “No, that’s not a good idea either.” So you just have to watch it and see and get a sense of what’s going on.

The reason why I’m hesitant is that they are going after artists very directly in Cuba right now. There are maybe three. Two, three, four artists, dissidents that are jailed. There was one guy who was doing stuff overseas that was just slightly critical of propaganda graphics. It was very detached from confrontation.

And when he came back to the island, he was jailed for about two months where he was tortured and dealt with in bad ways. And eventually he was allowed to leave as long as he took another dissident with him to Poland, I think.

And, of course this stuff doesn’t hit the news in the US, but I’m watching it all the time. And so I’m going to just wait it out for a year, two-three years and see how it goes. I’m not out there confronting the dictatorship directly. As the ones that are in jail put out a song that was very Directly a confrontation of the government and then they were put in jail and they’re still in jail. There was a big revolt in 2011, which they quashed. And they were very violent and disgusting. And I don’t really have any interest in dealing with the Cuban government in any way.

Rodriguez continues to receive commissions from publishers around the world

George Gendron: Books and magazine pieces develop a life of their own. I was publishing one of the first major pieces anywhere about climate change. And a friend of mine knew that we were publishing it and said, “Can you send me an advanced copy?” And I said, “Look, I’ll send you a copy of the galleys. But you have to promise me one thing: Read it and then send it to someone that you think would appreciate it with the same request.” So I sent it to him, and then maybe nine months later, out of the blue, I got the original set of galleys back from a journalist in Moscow. And all of these different people had put their name and their location, and little comments on the story. It was astonishing.

Edel Rodriguez: And yeah I’m already seeing that. And people are sending emails like, “Hey, I got a copy of your book.” The other thing we want to do is I want it to come out in Spanish. When it comes out in Spanish, I think it’s going to be more complex.

The thing that I’ve always done with communists—I have three uncles that were big in the party. Actually my father’s cousins, so there would be my cousins—I would go to their house and I would have fights with them when I would go to Cuba. And I would just throw truth at people. You say, “What is wrong in the book? What is not accurate? Where did I lie?” Everything happened, so I just made a document of what occurred.

When I would go to their house, I would have discussions about the system there, and it was mostly like, “Why do you get to travel as a member of the Communist party to Prague, and Europe, and these great hotels?” And at the time, Cubans couldn’t travel. It was illegal for any Cuban to leave the country. “Why can you travel and why can my aunt not travel?” And they would have no answer for that.

So I just have discussions with people like that directly. So if I'm at the airport and someone pulls me over, I will just say, “Okay, here’s the book. Yes, I made it. Tell me where I’m wrong. What did I write that is wrong? I’m a writer and I’m an artist. What is not true here? Did I make up anything? No. You guys had a boatlift, you sent prisoners out, you did this, and you did that. I made a book about it.”

Because what happens in Cuba is they don’t talk about these events. They don’t talk about anything that’s negative. People in Cuba don’t really know that much about the boatlift and what was done there because the government censors information. And I made this because I am seeing a lot of the same behaviors that were happening in Cuba and the dictatorship happening in this country.

Look how everyone behaved around Trump, right? They just let him do whatever he wanted. No one confronted him. In his administration, no one said, “You can’t do this. This is crazy.” And if you keep that going, and you don’t confront people, you end up at an insurrection. You end up at a government of 350 million people that is taken over by a dictator.

It is insane what this country is doing. This flirting with disaster. With a country of 350 million people. I lived in a country of 8 to 10 million people, Cuba. Look what it did there. Look what it’s done in Venezuela, a country of 35 million. Venezuela is 10 times the disaster that Cuba is. People are in the street. They can’t eat. Can you imagine a dictatorship in this country? It’s a gigantic disaster, and we keep flirting with it.

George Gendron: My final question for you then is are you planning on keeping it up?

Edel Rodriguez: I really don’t love painting this guy. There’s nothing attractive about it. There are people that buy prints from me and I’m like, “What are you gonna do with this thing?” And they’re generally collectors, people that collect items for historical importance. But there’s nothing attractive—I don’t have any paintings of him up in my house. But if someone calls me and says, “Hey, we’ve got a cover on this topic.” Yeah, of course I’ll do it.

What drove me last time was to urge people to pay attention. Urge people to know what was actually happening. I don’t have that same drive to do that right now because, Dude, you know it! I warned you already. And you had an insurrection!

I was doing work in 2016 that was warning and showing that this could happen—an insurrection and a takeover of the government could happen. It happened, right? And you’re still considering voting for the same person? I don’t know how I could communicate with that person.

Related Stories